CBR2: A Case-Based Reasoning Framework with Dual Retrieval Guidance for Few-Shot KBQA

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Ontology-constrained contextual knowledge: concept hierarchies and factual triples relevant to the question;

- Dual-source retrieved reasoning cases: one set retrieved via semantic similarity, and the other via function-level structural similarity.

- We propose CBR2, a novel case-based reasoning framework with dual retrieval guidance for single-pass symbolic program generation in few-shot KBQA.

- We design a dual-view case retrieval mechanism that captures both semantic similarity and function-level structural similarity, enabling generalization without iterative correction.

- We unify structured ontology knowledge and retrieved reasoning cases into a single, structure-aware prompt, effectively integrating symbolic constraints with reasoning exemplars.

2. Related Works

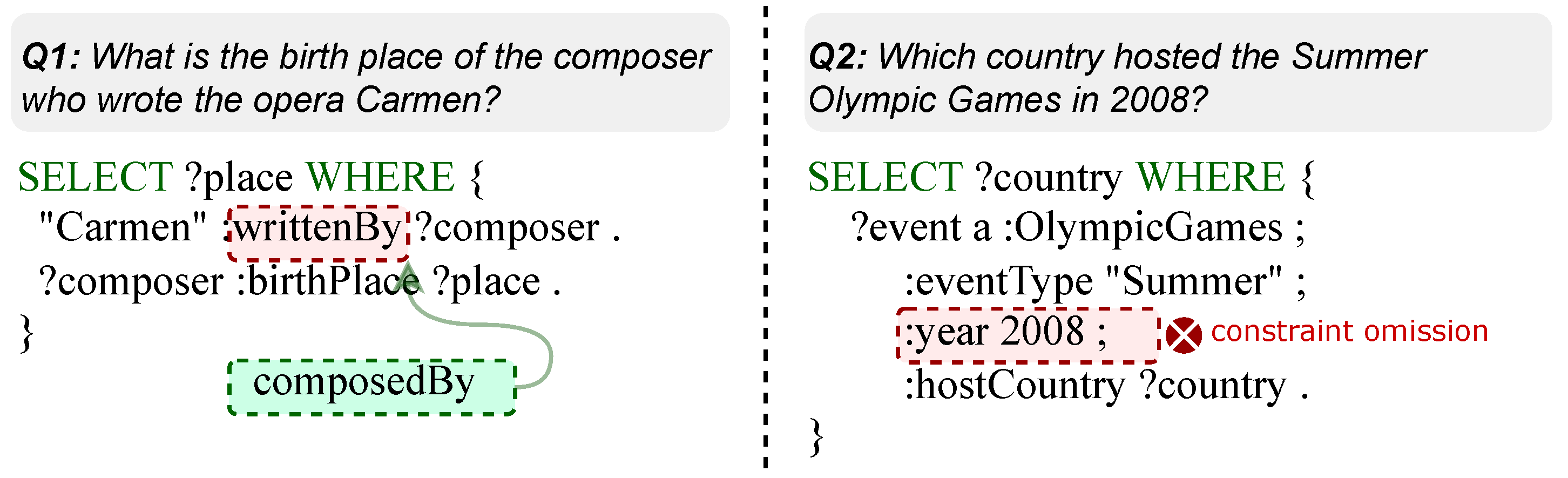

2.1. Semantic Parsing-Based KBQA

2.2. LLM-Based Symbolic Reasoning

- (1)

- Rule-guided interactive reasoning. This paradigm retrieves symbolic rules or structured templates from the knowledge schema and incrementally constructs programs under these constraints, with the LLM selecting actions or filling parameters at each step. Representative methods include Rule-KBQA [14], which adopts rule-guided prompting for controllable reasoning in complex KBQA; KBQA-o1 [34], which interacts with the KB environment through an agent for stepwise logical form generation; Inter-KBQA [3], which uses interpretable symbolic action sequences to construct programs step-by-step; FlexKBQA [35], which introduces dynamic schema constraint adaptation to balance flexibility and structural control; and MusTQ [36], which targets multi-step temporal KGQA by integrating rule-based temporal operators into the program generation process. These approaches ensure structural validity and interpretability, but rely on explicit rule repositories and require multiple inference rounds.

- (2)

- Multi-turn correction strategies. Another line of research first generates an initial program in one pass and then iteratively refines it through prompt rewriting, self-correction, or feedback-based validation [4,5,37,38]. For example, CodeAlignKGQA [5] formulates complex KGQA as knowledge-aware constrained code generation and applies multi-turn code alignment to progressively fix logical and semantic errors; SymKGQA [4] combines symbolic reasoning structures with execution feedback to iteratively refine logic, enhancing interpretability and execution accuracy; FUn-FuSIC [39] introduces an iterative repair loop that uses a suite of strong and weak verifiers to successively refine candidate logical forms; and prompt design techniques from related tasks [40], have been adapted to KBQA to improve structural alignment and reduce logical errors. While more robust to initial mistakes, these approaches incur additional latency and may suffer from inconsistencies between structural logic and factual grounding.

2.3. Case-Based Reasoning in KBQA

3. Preliminaries

3.1. Knowledge Base and Ontology Structure

3.2. KoPL Logic Formalism

3.3. Few-Shot KBQA Problem Definition

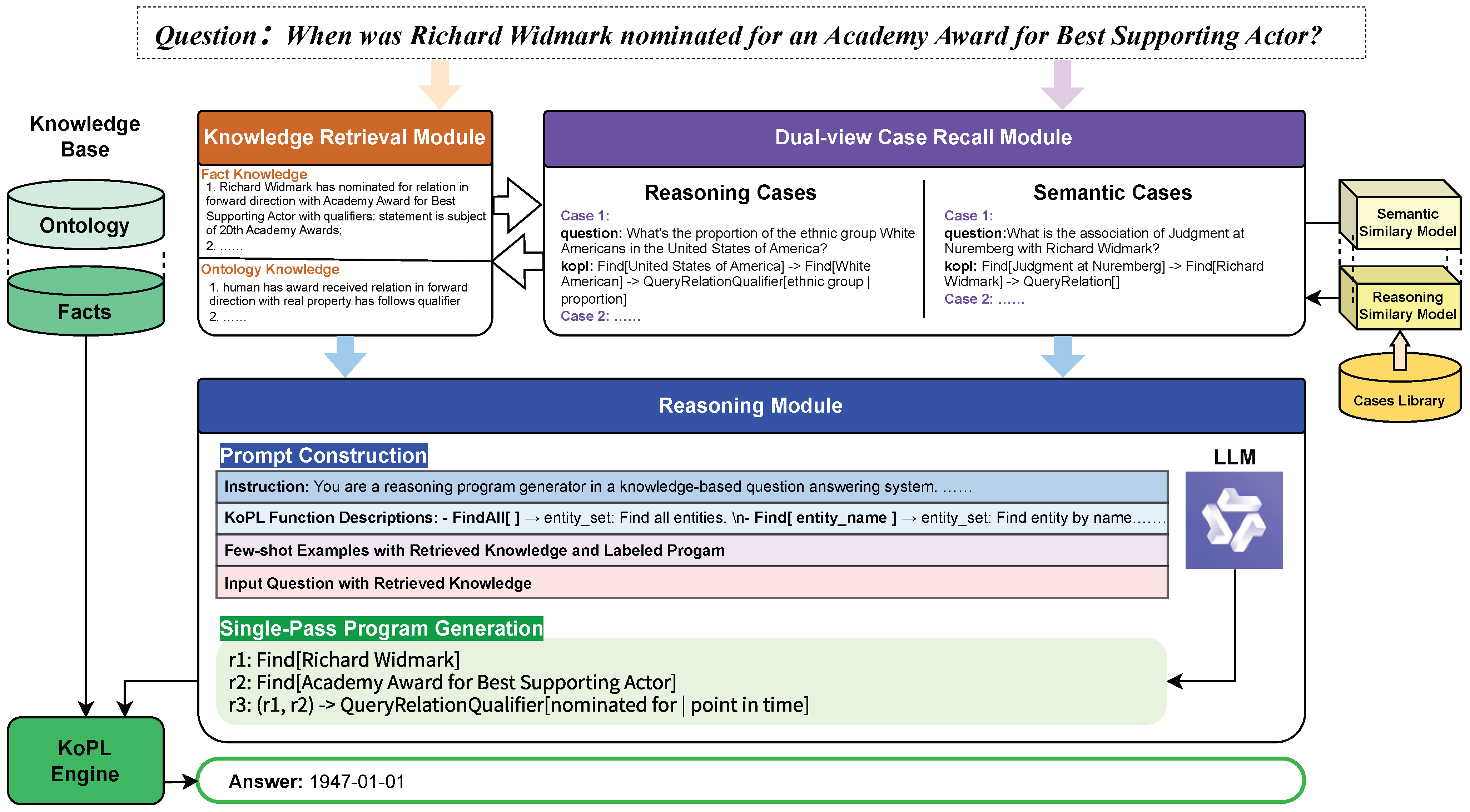

4. CBR2 Framework

- (1)

- Knowledge Retrieval—The system retrieves ontology axioms and factual triples relevant to the input question to form a symbolic context. For example, for the question “When was Richard Widmark nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor?”, the retrieved facts include “Richard Widmark has nominated for relation in forward direction with Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor”. The ontology slice further provides schema constraints such as “human has award received relation in forward direction with real property has follows qualifier”. Together, these two sources supply the symbolic background necessary for program grounding and execution.

- (2)

- Dual-View Case Retrieval—The system retrieves exemplar reasoning cases from two complementary perspectives. The semantic-view model recalls questions involving similar topics (e.g., awards or nominations), whereas the structural-view model identifies KoPL programs with reasoning patterns similar to the target query. For this example, the latter often surfaces chains such as Find → Find → QueryRelationQualifier, which match the required reasoning structure.

- (3)

- Prompt Construction—The retrieved knowledge and exemplar cases are encoded into a unified, structure-aware prompt . The prompt contains system instructions, KoPL function descriptions, fact and ontology snippets, and labeled few-shot examples. By embedding these symbolic constraints and structurally similar exemplars directly into the prompt, the model is guided at both semantic and structural levels during program generation.

- (4)

- Single-Pass Program Generation—The LLM decodes the entire KoPL program in a single step, which is then executed over the knowledge base to obtain the final answer. In the running example, executing the generated program yields the answer “1947-01-01”.

4.1. Knowledge Retrieval

- Ontology triples: schema-level relations such as instanceOf, subclassOf, and hasAttribute, which provide type constraints and concept hierarchies.

- Factual triples: entity-level assertions that capture real-world facts.

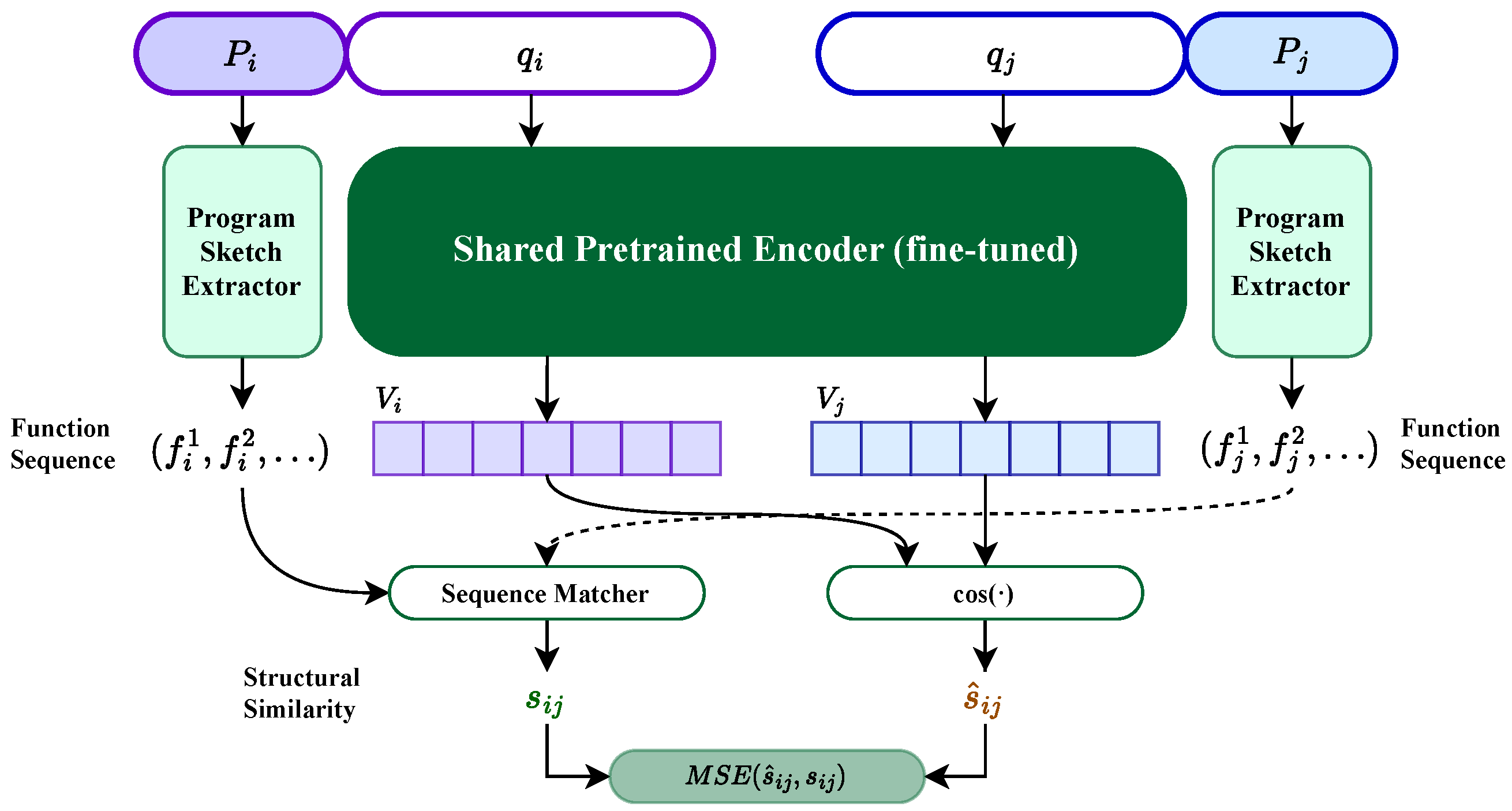

4.2. Dual-View Case Retrieval

4.3. Prompt Construction

4.4. Single-Pass Program Generation

5. Experimental Setup

5.1. Datasets

5.2. Baselines

- BART (SPARQL) [23]: a fully supervised seq2seq parser trained to generate SPARQL queries.

- GraphQ IR [8]: represents queries as graph-structured intermediate forms to preserve compositional semantics and enable precise mapping from natural language to executable queries.

- NSM (SE) [17]: neural symbolic machine with search-based execution, used for MetaQA.

- TransferNet [51]: knowledge transfer across domains for semantic parsing, used for MetaQA.

- FlexKBQA [35]: leverages large language models to generate executable KB queries with minimal task-specific supervision.

- Inter-KBQA [3]: interactive KBQA with schema-level rule retrieval and step-wise execution.

- SymKGQA [4]: schema-constrained symbolic program generation with GPT-4.

- Rule-KBQA [14]: rule-guided symbolic reasoning for complex KBQA.

- CodeAlignKGQA [5]: multi-turn code alignment and correction for KBQA programs.

5.3. Implementation Details

5.4. Evaluation Metrics

6. Results and Discussion

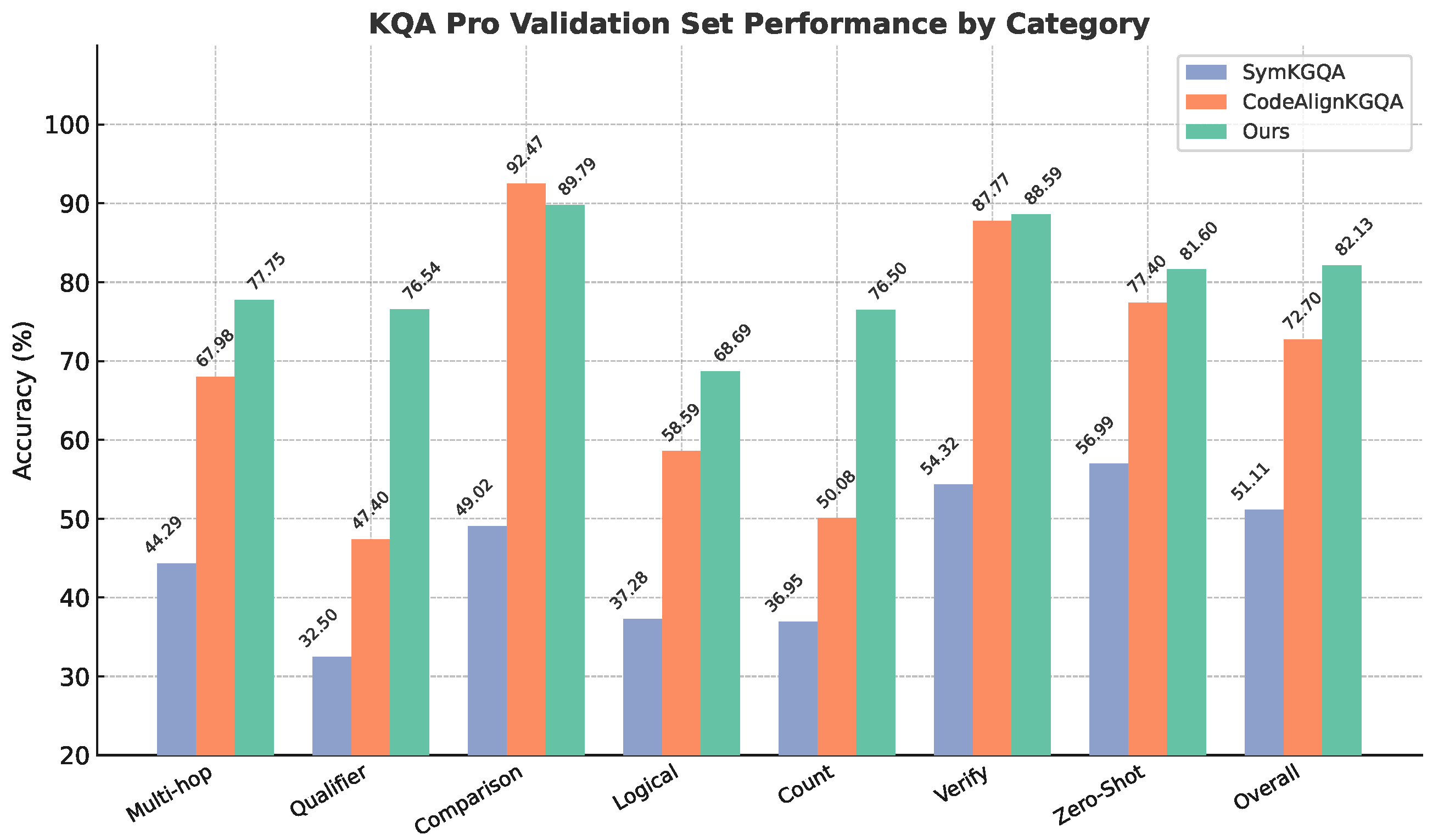

- RQ1: Can a single-pass generation framework match or surpass the performance of exist multi-turn generation methods? This directly evaluates our core motivation of avoiding iterative decoding without sacrificing accuracy.

- RQ2: Can CBR2 maintain stable generalization performance across different reasoning types? We investigate its robustness by conducting category-wise analysis on diverse reasoning patterns.

- RQ3: How well does CBR2 generalize across datasets? We assess its cross-domain applicability by comparing performance on two distinct KBQA benchmarks.

- RQ4: What is the contribution of each component in CBR2? We quantify the impact of knowledge retrieval, dual-view case retrieval, and structure-aware prompting via ablation studies.

6.1. RQ1: Baseline Comparison

6.2. RQ2: Performance Across Reasoning Categories

6.3. RQ3: Generalization Across Datasets

6.4. RQ4: Ablation Study

6.5. Error Case Study

7. Conclusions and Future Work

7.1. Summary

7.2. Limitations

7.3. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. In Proceedings of the 34th Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–12 December 2020; Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M., Lin, H., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 33, pp. 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; et al. Llama 2: Open Foundation and Fine-Tuned Chat Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.09288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.; Bao, J.; Zhao, W. Interactive-KBQA: Multi-Turn Interactions for Knowledge Base Question Answering with Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; Volume 1, pp. 10561–10582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Kumar, N.; Bedathur, S. SymKGQA: Few-shot knowledge graph question answering via symbolic program generation and execution. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; Volume 1, pp. 10119–10140. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, P.; Kumar, N.; Jagannath, S.B. Aligning Complex Knowledge Graph Question Answering as Knowledge-Aware Constrained Code Generation. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 19–24 January 2025; pp. 3952–3978. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Tong, L.; Yang, J.; Xue, L.; Huang, K.; Xiao, G. Fuzzy Symbolic Reasoning for Few-Shot KBQA: A CBR-Inspired Generative Approach. In Proceedings of the Case-Based Reasoning Research and Development, ICCBR 2025, Biarritz, France, 30 June–3 July 2025; Bichindaritz, I., López, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 96–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Jian, Y.; Xiao, G. Knowledge-injected Stepwise Reasoning on Complex KBQA. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, IJCNN 2024, Yokohama, Japan, 30 June–5 July 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Cao, S.; Shi, J.; Sun, J.; Tian, Q.; Hou, L.; Li, J.; Zhai, J. GraphQ IR: Unifying the Semantic Parsing of Graph Query Languages with One Intermediate Representation. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–11 December 2022; pp. 5848–5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Karlsson, B.F.; Ma, T.; Qu, Y.; Lin, C.Y. TIARA: Multi-grained Retrieval for Robust Question Answering over Large Knowledge Base. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–11 December 2022; pp. 8108–8121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelam, S.; Sharma, U.; Karanam, H.; Ikbal, S.; Kapanipathi, P.; Abdelaziz, I.; Mihindukulasooriya, N.; Lee, Y.S.; Srivastava, S.; Pendus, C.; et al. SYGMA: A System for Generalizable and Modular Question Answering Over Knowledge Bases. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2022, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–11 December 2022; pp. 3866–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Pahuja, V.; Cheng, G.; Su, Y. Knowledge Base Question Answering: A Semantic Parsing Perspective. In Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Automated Knowledge Base Construction, London, UK, 3–5 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Li, S.; Ji, H. Code4Struct: Code Generation for Few-Shot Event Structure Prediction. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–14 July 2023; Volume 1, pp. 3640–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.; Kumar, P.; Bhat, R.; Murthy, R.; Contractor, D.; Tamilselvam, S. Prompting with Pseudo-Code Instructions. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; pp. 15178–15197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wen, L.; Zhao, W. Rule-KBQA: Rule-guided reasoning for complex knowledge base question answering with large language models. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 19–24 January 2025; pp. 8399–8417. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S.; Chinta, A.; Kim, T.; Sharma, T.A.; Tur, D.H. Premise-Augmented Reasoning Chains Improve Error Identification in Math reasoning with LLMs. In Proceedings of the Forty-second International Conference on Machine Learning, 13–19 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yih, S.W.t.; Chang, M.W.; He, X.; Gao, J. Semantic parsing via staged query graph generation: Question answering with knowledge base. In Proceedings of the Joint Conference of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the ACL and the 7th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing of the AFNLP, Beijing, China, 26–31 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, C.; Berant, J.; Le, Q.; Forbus, K.D.; Lao, N. Neural Symbolic Machines: Learning Semantic Parsers on Freebase with Weak Supervision. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 July–4 August 2017; Volume 1, pp. 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Jiang, J. Query Graph Generation for Answering Multi-hop Complex Questions from Knowledge Bases. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintz, M.; Bills, S.; Snow, R.; Jurafsky, D. Distant supervision for relation extraction without labeled data. In Proceedings of the Joint Conference of the 47th Annual Meeting of the ACL and the 4th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing of the AFNLP, Suntec, Singapore, 2–7 August 2009; pp. 1003–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, C.; Norouzi, M.; Berant, J.; Le, Q.V.; Lao, N. Memory augmented policy optimization for program synthesis and semantic parsing. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 2–8 December 2018; pp. 10015–10027. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3327546.3327665 (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Dong, L.; Wei, F.; Zhou, M.; Xu, K. Question answering over freebase with multi-column convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 7th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, Beijing, China, 26–31 July 2015; Volume 1, pp. 260–269. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; Volume 1, pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, M.; Liu, Y.; Goyal, N.; Ghazvininejad, M.; Mohamed, A.; Levy, O.; Stoyanov, V.; Zettlemoyer, L. BART: Denoising Sequence-to-Sequence Pre-training for Natural Language Generation, Translation, and Comprehension. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 7871–7880. [Google Scholar]

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, R.; Lin, C.; Thomson, S.; Chen, C.; Roy, S.; Platanios, E.A.; Pauls, A.; Klein, D.; Eisner, J.; Van Durme, B. Constrained Language Models Yield Few-Shot Semantic Parsers. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Online, Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 7–11 November 2021; pp. 7699–7715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholak, T.; Schucher, N.; Bahdanau, D. PICARD: Parsing Incrementally for Constrained Auto-Regressive Decoding from Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Online, Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 7–11 November 2021; pp. 9895–9901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, P.; Cheng, G.; Qu, Y. Skeleton parsing for complex question answering over knowledge bases. J. Web Semant. 2022, 72, 100698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.; Nair, P.A.; Kaur, J.N.; Usbeck, R.; Biemann, C. Modern baselines for SPARQL semantic parsing. In Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Madrid, Spain, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 2260–2265. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, D.; Pascazio, L.; Akroyd, J.; Mosbach, S.; Kraft, M. Leveraging text-to-text pretrained language models for question answering in chemistry. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 13883–13896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, B.; Duan, Y.; Yang, X.; He, D.; Yan, S. Text2SPARQL: Grammar Pre-training for Text-to-QDMR Semantic Parsers from Intermediate Question Decompositions. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing, Auckland, New Zealand, 2–6 December 2024; pp. 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Zou, L.; Zhang, X. A State-transition Framework to Answer Complex Questions over Knowledge Base. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October–4 November 2018; pp. 2098–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhou, K.; Dong, Z.; Ye, K.; Zhao, X.; Wen, J. StructGPT: A General Framework for Large Language Model to Reason over Structured Data. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, EMNLP 2023, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; Bouamor, H., Pino, J., Bali, K., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Kerrville, TX, USA, 2023; pp. 9237–9251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Xu, C.; Tang, L.; Wang, S.; Lin, C.; Gong, Y.; Ni, L.M.; Shum, H.; Guo, J. Think-on-Graph: Deep and Responsible Reasoning of Large Language Model on Knowledge Graph. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2024, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H.; E, H.; Guo, Y.; Lin, Q.; Wu, X.; Mu, X.; Liu, W.; Song, M.; Zhu, Y.; Luu, A.T. KBQA-o1: Agentic Knowledge Base Question Answering with Monte Carlo Tree Search. In Proceedings of the Forty-Second International Conference on Machine Learning, Vancouver, Canada, 13–19 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Fan, S.; Gu, Y.; Li, X.; Duan, Z.; Dong, B.; Liu, N.; Wang, J. Flexkbqa: A flexible llm-powered framework for few-shot knowledge base question answering. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 18608–18616. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Qu, J.; Liu, A.; Chen, Z.; Zhi, H. MusTQ: A Temporal Knowledge Graph Question Answering Dataset for Multi-Step Temporal Reasoning. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024, Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; pp. 11688–11699. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X.; Yavuz, S.; Hashimoto, K.; Zhou, Y.; Xiong, C. RNG-KBQA: Generation Augmented Iterative Ranking for Knowledge Base Question Answering. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Dublin, Ireland, 22–27 May 2022; Volume 1, pp. 6032–6043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Zhang, S.; Ng, P.; Zhu, H.; Li, A.H.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y.; Wang, W.Y.; Wang, Z.; Xiang, B. DecAF: Joint Decoding of Answers and Logical Forms for Question Answering over Knowledge Bases. In Proceedings of the The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2023, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sawhney, R.; Yadav, S.; Bhattacharya, I.; Mausam. Iterative Repair with Weak Verifiers for Few-shot Transfer in KBQA with Unanswerability. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2025, Vienna, Austria, 27 July–1 August 2025; pp. 24578–24596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zou, W.; Ri, N.; Tae, J.; Zhang, E.; Cohan, A.; Radev, D. Enhancing Text-to-SQL Capabilities of Large Language Models: A Study on Prompt Design Strategies. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; pp. 14935–14956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aamodt, A.; Plaza, E. Case-based reasoning: Foundational issues, methodological variations, and system approaches. AI Commun. 1994, 7, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Zaheer, M.; Thai, D.; Godbole, A.; Perez, E.; Lee, J.Y.; Tan, L.; Polymenakos, L.; McCallum, A. Case-based Reasoning for Natural Language Queries over Knowledge Bases. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Online, Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 7–11 November 2021; pp. 9594–9611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luo, X.; Lu, G. GS-CBR-KBQA: Graph-structured case-based reasoning for knowledge base question answering. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 257, 125090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Godbole, A.; Naik, A.; Tower, E.; Zaheer, M.; Hajishirzi, H.; Jia, R.; Mccallum, A. Knowledge Base Question Answering by Case-based Reasoning over Subgraphs. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022; Volume 162, pp. 4777–4793. [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi, A.; Chakrabarti, S.; Sarawagi, S. Structured case-based reasoning for inference-time adaptation of text-to-sql parsers. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; Volume 37, pp. 12536–12544. [Google Scholar]

- Dutt, R.; Bhattacharjee, K.; Gangadharaiah, R.; Roth, D.; Rose, C. PerKGQA: Question Answering over Personalized Knowledge Graphs. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2022, Seattle, WA, USA, 10–15 July 2022; pp. 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Shi, J.; Pan, L.; Nie, L.; Xiang, Y.; Hou, L.; Li, J.; He, B.; Zhang, H. KQA Pro: A Dataset with Explicit Compositional Programs for Complex Question Answering over Knowledge Base. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Dublin, Ireland, 22–27 May 2022; Volume 1, pp. 6101–6119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.; Jordan, M.I.; Klein, D. Learning Dependency-Based Compositional Semantics. Comput. Linguist. 2013, 39, 389–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Douze, M.; Jégou, H. Billion-scale similarity search with GPUs. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2019, 7, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dai, H.; Kozareva, Z.; Smola, A.; Song, L. Variational reasoning for question answering with knowledge graph. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Cao, S.; Hou, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, H. TransferNet: An Effective and Transparent Framework for Multi-hop Question Answering over Relation Graph. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Online, Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 7–11 November 2021; pp. 4149–4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.H.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, NeurIPS 2022, New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wei, J.; Schuurmans, D.; Le, Q.V.; Chi, E.H.; Narang, S.; Chowdhery, A.; Zhou, D. Self-Consistency Improves Chain of Thought Reasoning in Language Models. In Proceedings of the The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2023, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, P.; Luo, K.; Lian, D.; Liu, Z. M3-Embedding: Multi-Linguality, Multi-Functionality, Multi-Granularity Text Embeddings Through Self-Knowledge Distillation. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024, Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; pp. 2318–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Hong Kong, China, 3–7 November 2019; Association for Computational Linguistics: Kerrville, TX, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, A.; Li, A.; Yang, B.; Zhang, B.; Hui, B.; Zheng, B.; Yu, B.; Gao, C.; Huang, C.; Lv, C.; et al. Qwen3 Technical Report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.09388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset | Hop | KoPL | Train | Valid | Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KQA Pro | – | ✓ | 94,376 | 11,797 | 11,797 |

| MetaQA | 1-hop | ✓ | 96,106 | 9992 | 9947 |

| 2-hop | ✓ | 118,980 | 14,872 | 14,872 | |

| 3-hop | ✓ | 114,196 | 14,274 | 14,274 |

| Method | Models | Hits@1 | SER% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fully Supervised | BART(SPARQL) | 83.28 | 8.2 |

| GraphQ IR | 79.13 | – | |

| Few-shot | FlexKBQA | 42.68 | – |

| LLM-ICL | 27.75 | – | |

| SymKGQA | 51.10 | 29.2 | |

| CodeAlignKGQA | 72.70 | 4.95 | |

| Few-shot (Ours) | CBR2 | 82.13 | 3.71 |

| Model | CT | QA | QAQ | QN | QR | QRQ | SA | SB | VF | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prompting | IO w/GPT-4 | 27 | 23 | 36 | 40 | 25 | 50 | 11 | 69 | 73 | 39.33 |

| CoT w/GPT-4 | 22 | 26 | 35 | 34 | 18 | 46 | 21 | 79 | 77 | 39.78 | |

| SC w/GPT-4 | 25 | 28 | 33 | 38 | 22 | 51 | 19 | 86 | 75 | 41.89 | |

| LLMs + KGs | Inter-KBQA | 74 | 83 | 64 | 73 | 73 | 59 | 80 | 61 | 80 | 71.89 |

| Rule-KBQA | 82 | 87 | 79 | 82 | 84 | 75 | 87 | 88 | 86 | 83.33 | |

| Ours | 83 | 84 | 85 | 81 | 85 | 81 | 81 | 91 | 86 | 84.11 |

| Method | Models | 1-Hop | 2-Hop | 3-Hop | SER% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fully Supervised | NSM (SE) | 97.2 | 99.9 | 98.9 | - |

| TransferNet | 97.5 | 100.0 | 100.0 | - | |

| Few-Shot (100 Shots) | SymKGQA | 99.1 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 0.2 |

| CodeAlignKGQA (Gemini Pro 1.0) | 99.2 | 99.7 | 99.8 | 0.0 | |

| CodeAlignKGQA (CodeLlama Ins.) | 99.6 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 0.0 | |

| Few-Shot (10 Shots) | Ours | 99.7 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 0.0 |

| Category | Model / Setting | CT | QA | QAQ | QN | QR | QRQ | SA | SB | VF | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full CBR2 (Ours) | 83 | 84 | 85 | 81 | 85 | 81 | 81 | 91 | 86 | 84.11 | |

| Target Program Format | Chain | 78 | 82 | 81 | 73 | 82 | 68 | 80 | 90 | 85 | 79.89 |

| Case Recall | -w/o reasoning case | 77 | 75 | 79 | 62 | 77 | 65 | 77 | 85 | 75 | 74.67 |

| -w/o semantic case | 63 | 64 | 57 | 52 | 68 | 63 | 56 | 79 | 70 | 63.56 | |

| random case | 31 | 37 | 11 | 26 | 43 | 11 | 25 | 42 | 46 | 30.22 | |

| Knowledge Recall | -w/o act knowledge | 77 | 74 | 69 | 71 | 81 | 60 | 76 | 85 | 83 | 75.11 |

| -w/o ont knowledge | 79 | 81 | 78 | 78 | 80 | 77 | 79 | 88 | 83 | 80.33 | |

| -w/o knowledge | 80 | 77 | 76 | 74 | 82 | 70 | 76 | 85 | 84 | 78.22 |

| Case 1: Semantic Grounding Error |

| Question: Which one of Pennsylvanian cities, with 717 as the local dialing code, has the lowest altitude above sea level? |

| Gold KoPL: r1: FindAll[] → FilterStr[local dialing code | 717] → FilterConcept[city of Pennsylvania] → SelectAmong[elevation above sea level | smallest] |

| Pred KoPL: r1: FindAll[] → FilterStr[local dialing code | 717] → FilterConcept[city of Pennsylvania] → SelectAmong[altitude above sea level | smallest] |

| Gold Answer: Harrisburg |

| Pred Answer: no |

| Case 2: Logical Reasoning Error |

| Question: How many popular musics are influenced by the band which has ISNI 0000 0001 2369 4269? |

| Gold KoPL: r1: FindAll[] → FilterStr[ISNI | 0000 0001 2369 4269] → FilterConcept[band] → Relate[influenced by | backward] → FilterConcept[popular music] → Count[] |

| Pred KoPL: r1: FindAll[] → FilterStr[ISNI | 0000 0001 2369 4269] → FilterConcept[band] → Relate[influenced by | forward] → FilterConcept[popular music] → Count[] |

| Gold Answer: 1 |

| Pred Answer: 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hu, X.; Li, T.; Xue, L.; Du, Z.; Huang, K.; Xiao, G.; Tang, H. CBR2: A Case-Based Reasoning Framework with Dual Retrieval Guidance for Few-Shot KBQA. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2026, 10, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010017

Hu X, Li T, Xue L, Du Z, Huang K, Xiao G, Tang H. CBR2: A Case-Based Reasoning Framework with Dual Retrieval Guidance for Few-Shot KBQA. Big Data and Cognitive Computing. 2026; 10(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Xinyu, Tong Li, Lingtao Xue, Zhipeng Du, Kai Huang, Gang Xiao, and He Tang. 2026. "CBR2: A Case-Based Reasoning Framework with Dual Retrieval Guidance for Few-Shot KBQA" Big Data and Cognitive Computing 10, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010017

APA StyleHu, X., Li, T., Xue, L., Du, Z., Huang, K., Xiao, G., & Tang, H. (2026). CBR2: A Case-Based Reasoning Framework with Dual Retrieval Guidance for Few-Shot KBQA. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 10(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc10010017