3.1. Most Influential Factors

The design of experiments was built with the JMP

® [

11] software. To determine the factors’ influence on the output, a two-stage screening design was selected. This kind of design makes it possible to sort out from a large sample of factors those that have a non-negligible role on the system output and those that have little influence. These designs lead to a reduction in the dimensions of the factor space and a simplification of the problem. In this screening design, the level of each factor corresponds to the boundaries of the variation range, i.e.,

and

as a coded variable. Consequently, the predicted output law is linear. The experimental design selected is a

fractional factorial design. These designs are subsets of the full factorial designs. Fractional factorial designs are a good choice when resources are limited and the number of factors in the design is large; see [

12] for more information. The simulations’ number of fractional designs was equal, here

. The screening design is listed in

Table 1.

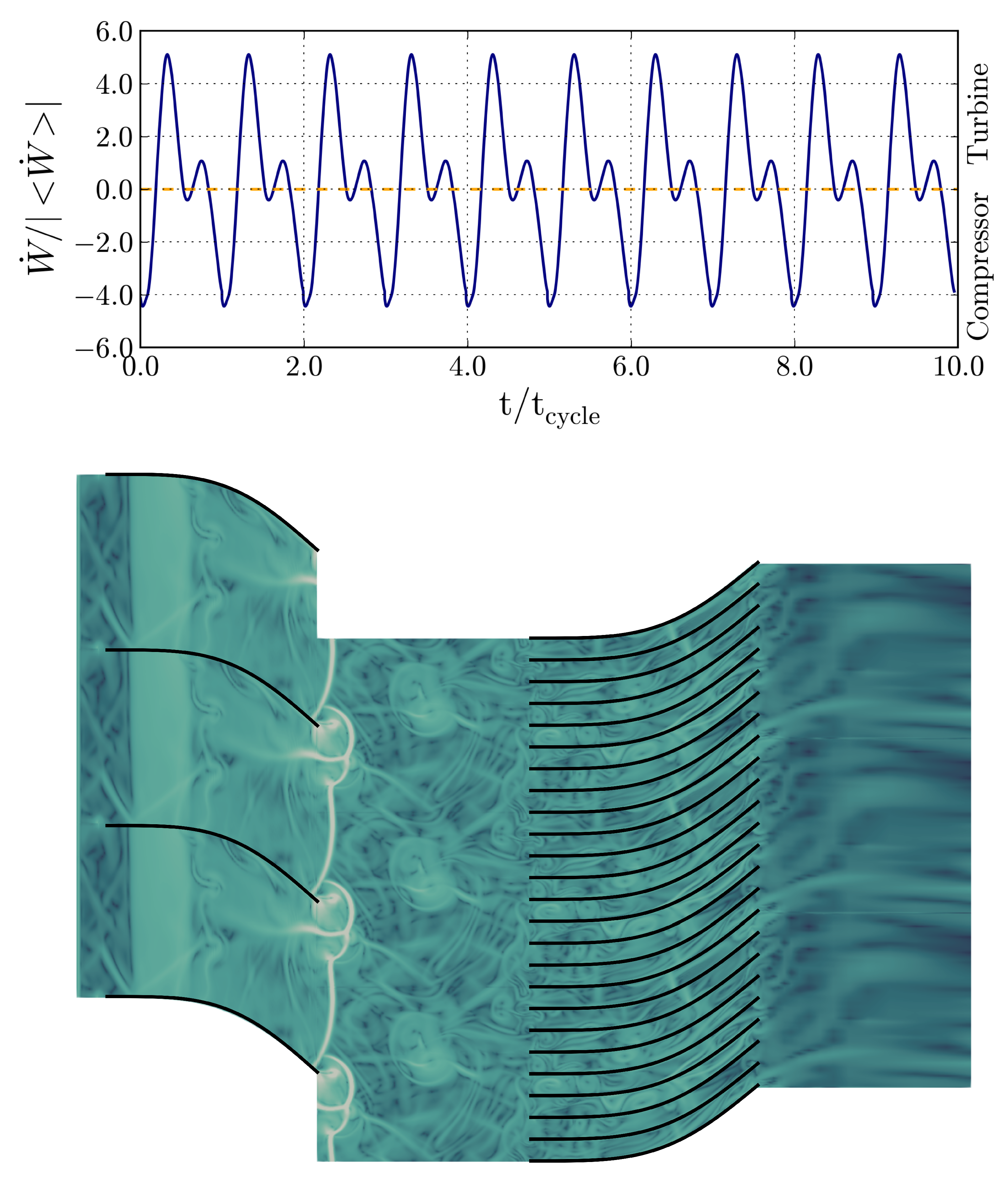

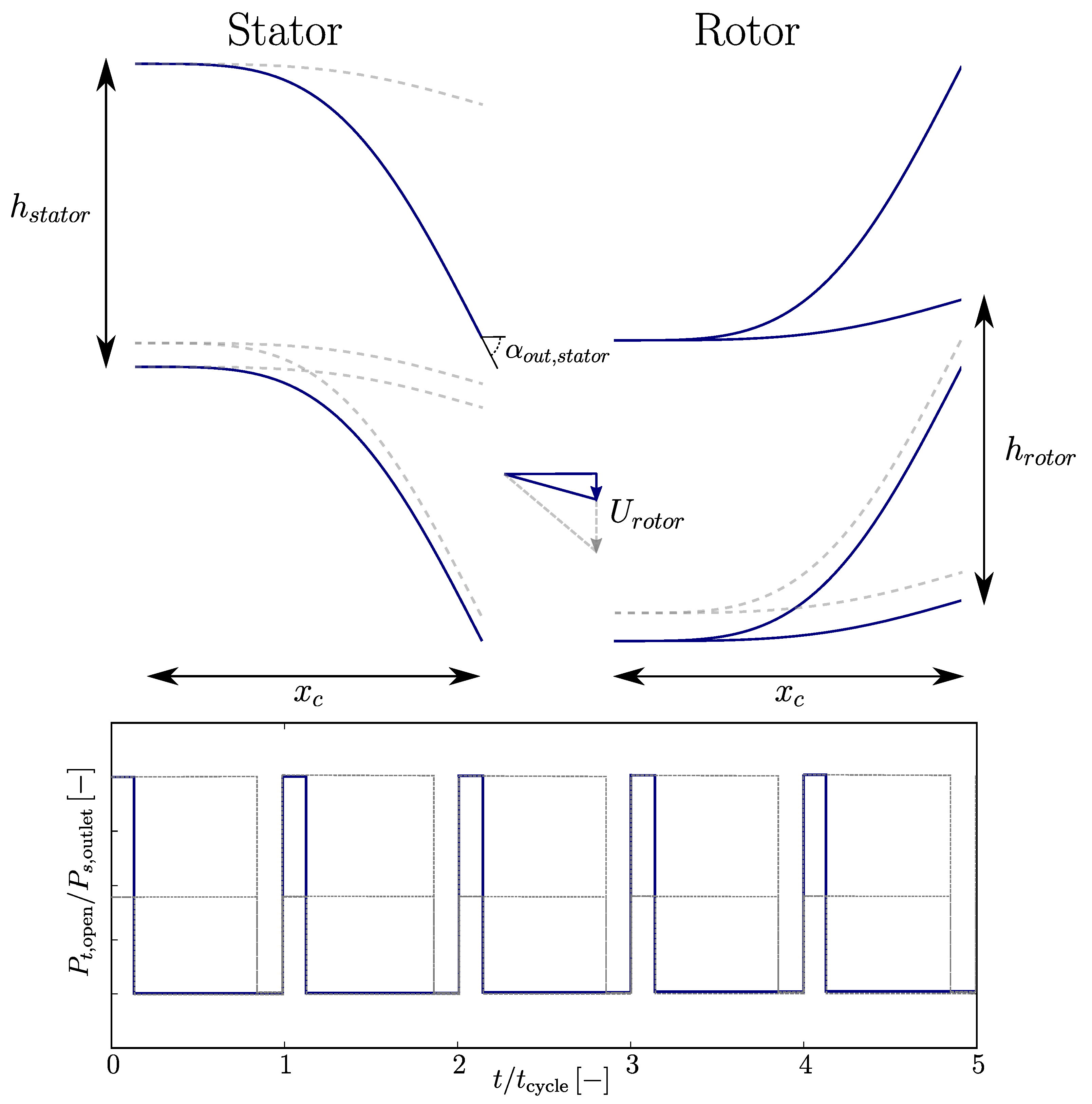

Screening design results are shown in

Table 1. Two additional responses besides the recovery efficiency

were proposed. Since the rotational speed is fixed, the strong decrease of mass-flow can make the compressor operating mode appear. The relative proportion of time in which this happens is quoted in %. Furthermore, the standard deviation of the work signal is reported in order to quantify the loading fluctuations. The recovery efficiency of many simulations is close to

; the turbine extracts almost no energy from the flow over a cycle. The system alternates between turbine and compressor phases. The balance between these modes is particularly visible on the temporal evolution of

for the simulation

in

Figure 2. Compressor modes are driven by waves that generate a greater force on the suction side of the blade than on the pressure side. The temporal evolution of

shows behaviours in agreement with the results of [

3]. The valve opening causes a shock wave propagation, which generates a work increase. The valve closing generates an expansion wave, which causes a work decrease. An instantaneous visualization of the density gradient is also shown in

Figure 2. This instantaneous visualization highlights the flow complexity.

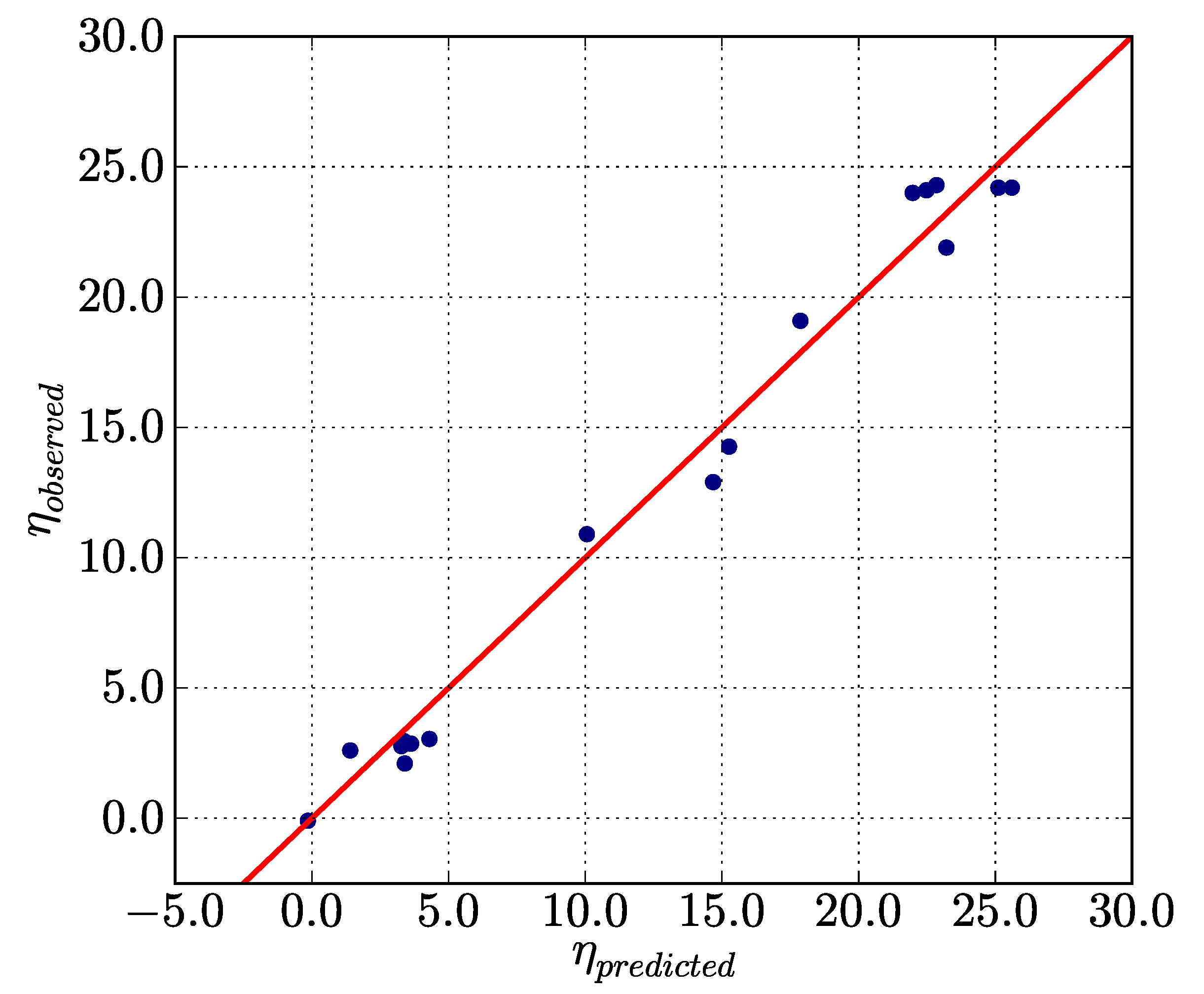

The linear prediction extracted from the screening phase is given in

Figure 3. It shows a fair accuracy

. Moreover, the distribution of the measured values in the observed performance range is relatively homogeneous, which gives confidence in the behavioural law prediction and legitimises the conclusions regarding the true influence of the different factors.

For the numerical experimental designs, the natural variability of the output can be considered as negligible. As a result, all factors in the design of experiments are statistically significant on the system output. However, some factors may be neglected by comparing the sensitivity values of the prediction model. A factor was considered to be noninfluential on the response when its sensitivity was less than of the maximum sensitivity of the model.

The sensitivity analysis showed that only six factors have a significant role in stage performance; see

Table 3. The influence of these factors was further investigated by calculating the response surface. Understanding in detail why factors

,

,

and

do not influence the turbine recovery efficiency is difficult with such a flow complexity. However, the spatial distribution of the time-averaged energy recovered shows no sensitivity to these parameters. This result will not be presented here.

3.2. Surface Response

The reduction of the number of factors makes it possible to carry out a more quantitative study of the system output thanks to the response surface methodology [

12]. The response surface modelling allows determining the factor that optimizes the output. For this design of experiments, the behaviour law prediction was performed by a quadratic function (see Equation (

5)) with

each selected factors.

In order to achieve a quadratic prediction of the output law, three levels for each factor must be considered in the simulations. In addition to the high

and low levels

, the central level 0 was added. For the calculation, the stator and rotor channels must be multiples of each other. The central value is then adjusted for

and

. The level of factors is indicated in

Table 4. In the same way as the screening design, the experimental design was constructed using [

11]. In order to minimize the simulations number, a D-optimality criterion was adopted for the design of experiments; see [

12]. The surface response design was based on twenty-eight simulations for six factors. The levels of the noninfluential factors on the output, namely

,

,

, and

, were taken at their high level

to carry out the simulations.

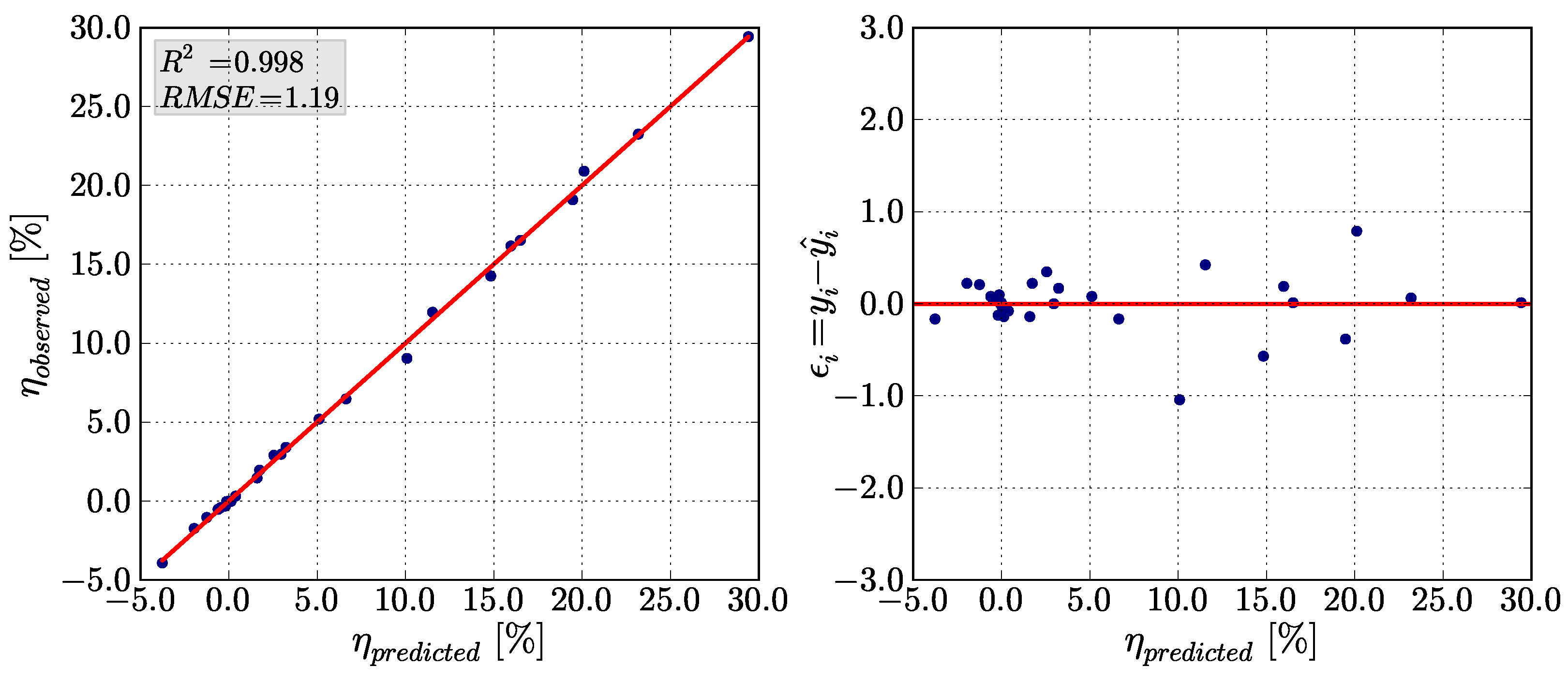

The results of the experimental design are provided in

Table 5. The response surface accuracy can be examined by investigating

Figure 4. It shows that the output law is very well modelled by the response surface

. The spatial distribution of the measured values in the observed performance range is relatively homogeneous, which ensures that the predicted output law can be trusted. The model quality is also assessed on the residual value

(

Figure 4). The residuals are small and have no outliers.

It is interesting to focus on a few particular simulations showing original behaviours. Simulations or revealed that it is possible, with the wrong set of parameters, to design a system operating exclusively in compressor mode, whereas the target was to design a turbine. shows a fairly marked compressor mode over a cycle (13.5%), whereas this simulation leads to the highest recovery efficiency observed.

The factor levels that optimize the response are shown in

Table 6. The maximum efficiency in the experimental domain is

. The result on the coded variables reveals that the real optimum of this system is outside the experimental domain. Indeed, except for

, the optimal value of the factors is located on the boundary of the experimental domain. This is promising since it means that it is possible with this system to extract more than

of the injected energy into the turbine over a valve cycle, if the experimental domain is redefined in order to find the global optimum. For comparison, the

value calculated for the usual turbofan is about

for the high-pressure turbine stage (

K,

K).

The position of the optimum gives the main trends for the design of a turbine fed by a pulsed flow, as far as 2D analysis can be applied. It reinforces the usefulness of the stator for this system. This result was not evidence since the instantaneous performance is dictated by the waves’ propagation, and not by the usual steady analysis expressed by Euler’s theorem. The stator must be composed of blades with a high solidity , which forces a large deviation to the flow. This kind of stator generates much more intense wave reflections and diffraction than if and were kept at their lowest levels. The reflections’ amplification causes an inlet energy flux reduction during the opening phases. The diffraction intensification, especially at the trailing edge, causes a large reduction in the transmitted waves’ intensity to the rotor. The rotor is then less sensitive to the flow unsteadiness. This behaviour can be seen by comparing the standard deviation of the work signal between Simulations and , where only stator geometrical parameters are modified.

The rotor solidity

must also be high (

Table 6). The sensitivity estimation of the response surface shows that this factor is the most important for the turbine design. Observations of the DOE results (

Table 5) prove that it is impossible to reach high efficiency when

is low. It is possible that this is due to the large recirculation zones that take place at the leading edge on the suction side of the rotor blades, and that persist more or less over time, when the stator geometrical factors are at their highest levels. When the size of these zones is of the order of magnitude of the pitch, pressure profiles on both sides of the rotor blade tend to be the same. Therefore,

must be high enough to overcome this difficulty.

Table 6 reveals that the turbine is more efficient to extract energy when high-pressure ratios are applied over a short ratio cycle. In addition to the stator design, low cycle ratios attenuate the energy injected into the turbine over a cycle, while high-pressure ratios increase it. This may seem contradictory. In addition, the unsteadiness related to the shock wave propagation during the valve opening is maximal for these cycle features. Indeed, for low cycle ratios, the upstream flow of the shock wave is mostly at rest in the stator. The downstream shock state is set by the inlet boundary condition, and the shock wave intensity is then maximal for this cycle feature (this explains the compressor phases on Simulation

). As explained, the stator reduces the unsteadiness, which propagates to the rotor. A compromise must therefore be found among

,

,

and

in order to reduce the energy flux through the turbine while maximizing the unsteadiness benefits within the rotor.

Finally, in order to minimize the drawbacks related to unsteadiness, more specifically compressor operation during the valve closing phase, must be as low as possible. The smaller , the lower the rotor speed compared to the characteristic bulk velocity.