1. Introduction

There is a growing demand for increased flexibility in modern steam turbines, both in Germany [

1] and globally [

2]. Notably, there is a demand for quick-start capability, which refers to the turbine’s ability to provide the desired output as rapidly as possible. Furthermore, all applications require multiple design points at partial load, rather than a limited set in the upper fifth of the power range. This requirement extends across thermal, mechanical, and electrical power.

Numerous papers and patents address the issue of rapid cold starts, focusing on modern drive methods that enable faster component warm-up. Gobrecht et al. [

3,

4] propose a technique in which the flow path downstream of the intermediate pressure turbine is sealed, thereby increasing the pressure and saturation temperature, which facilitates a quicker heating of the front machine components. The initial parameters for the high-pressure turbine are specified as 620 °C and 300 bar, with a reported time savings of one hour. Quinkertz [

5] suggests the use of externally generated steam and bypassing of the last stage.

Thermal loads can vary due to different process heat requirements. These may involve facilities in the paper industry, chemical industry, district heating systems or other sectors. Mechanical power refers to steam turbines, which, for instance, are employed as drives for large machinery and systems. Electrical power pertains to the flexible generation of electricity. This controllability is crucial for stabilising power grids. This is of particular importance during the energy transition in many European and North American countries, especially when renewable energy sources are prioritised for grid integration.

Operation at partial load leads to significant thermal changes in steam turbine components, some of which are subject to high stress, particularly due to load changes [

6]. Through open and closed circumferential segments, mass flow can be saved in comparison to throttle control [

7]. However, the machines are supplied with live steam asymmetrically. Control stages mitigate this effect, but do not completely equalise it. Consequently, hot circulating flow regimes develop, which also heat up the contacting components significantly. This can cause hotter spots and colder spots, meaning transient operation sometimes results in high thermal stresses. These must be investigated to design steam turbine components under high thermal loads in terms of mechanical load and lifetime prediction [

8].

Modern measurement technology must recognise and meet the state-of-the-art requirements. This concerns temporal resolution and enhanced measurement accuracy. Kaiser [

9] provides a comprehensive overview of thermal measurements. This applies in particular to measurements of heat-flux sensors based on the principle of substitute walls. The medium of steam is considerably more complex to experiment with than using tempered compressed air. In addition, its operation needs much more know-how, is expensive, especially in terms of components and manpower, and is time-consuming. Moreover, moisture can cause a short-circuit in electrically exposed conductors. Nevertheless, new types of sensors must be developed in order to demonstrate predicted effects. For this purpose, one starts with straightforward measurable effects at easily accessible locations and successively proceed with measuring success to more complex phenomena at machine sections that are difficult to access.

Heat transport in side spaces of steam turbines are not fully understood yet. Although steam turbines have been providing electricity and heat for a long time, the specification of thermal boundary conditions is still imprecise in some machine sections. Numerical engineers require valid measurement data as reference points for the specification of thermal boundary conditions to correctly calculate thermal expansions during operation, which have an impact on deformation and also on the split flange and its tightness. Component life time is also significantly affected by these influences.

Research on side spaces has been conducted intermittently across the globe. Several studies from Eastern Europe during the 1980s and 1990s focused extensively on steam turbines. At that time, for instance, machines of the type K-200-130 (or bigger) were analysed [

10,

11,

12]. Both casings and valves [

13], as well as rotors [

14], were investigated. Correlations were established for heat transfer as a function of power for both the rotor and side chambers. The findings of this work were subsequently compared with the existing literature [

10].

In the 2010s, several test rigs were set up to investigate heat transfer. Tempered compressed air was often used as a medium instead of steam. Spura et al. [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19] built a test rig called SiSTeR (Side Space Test Rig). The test rig was equipped with two independent measurement methods to characterise the heat transfer. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) were conducted in parallel. The results show good agreement. For the formulation of equations of heat transfer along the rotor axis, functions similar to Gaussian distributions (“bell curve”) were established.

Adinarayana [

20] built a 1:2 test rig pressurised with steam for thermal measurement. This work incorporated eight heat-flux sensors according to the design of Gardon [

21]. The measured values of the heat transfer coefficient exceeded 1000 W/m

2K during the start and remained within the three-digit range during steady-state operation, depending on the measurement position. Moroz et al. [

6] performed a thermo-structural analysis during transient operations for a 30 MW steam turbine, which was accompanied by a test campaign on a full-scale test rig. The focus was on modelling and numerical simulation. Therefore, just a few thermocouples on the outer surface of the steam turbine casing were used as initial data. Heat fluxes were not measured. No error bars are provided either.

The absence of comprehensive experimental work and corresponding measurement data suggests that there are very few steam-operated test rigs in which heat flows or heat transfers have been measured or that the manufacturers leave these tests unpublished. The authors are not aware of many studies on full-scale test rigs using heat-flux sensors. This scientific gap is intended to be progressively closed with the results of this study.

Experimental and numerical work should ideally be conducted simultaneously. On the one hand, numerical codes must be validated with experimental data. On the other hand, functional codes can predict phenomena that may require new experimental investigations. In this way, each discipline can contribute new insights to the other. In the ideal case, experimental and numerical results align.

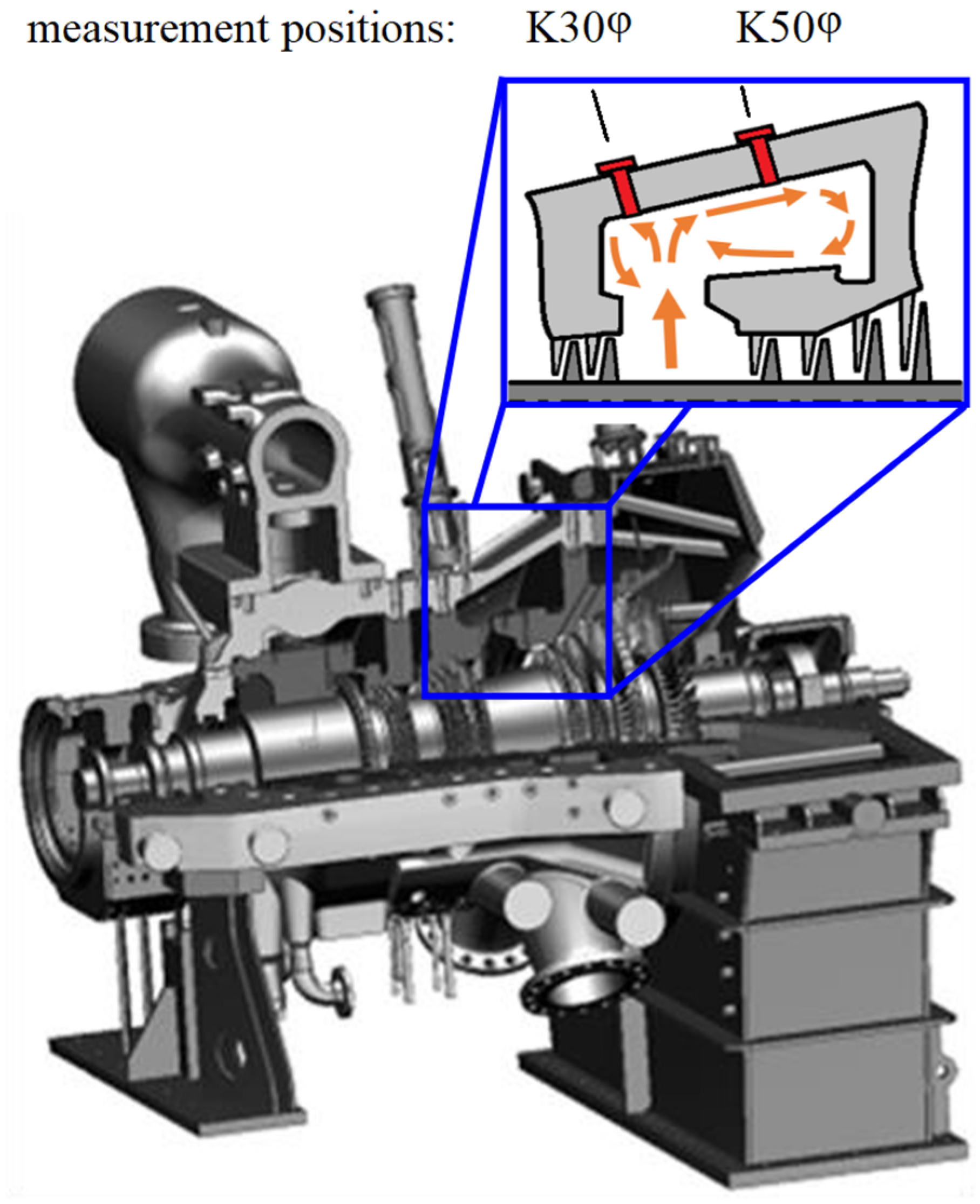

In this work, a novel thermal sensor was applied to a side space of a steam turbine to improve the knowledge regarding heat transfer. The general setup of the test rig used for experimental investigation presented in this work is described in detail by Brunn et al. [

22,

23]. Weigel et al. [

24,

25] investigated the heat transfer of this machine with a focus on transient measurement during start-up. Especially, a method was used to measure the adiabatic wall temperature with proprietary sensors.

2. Sensor

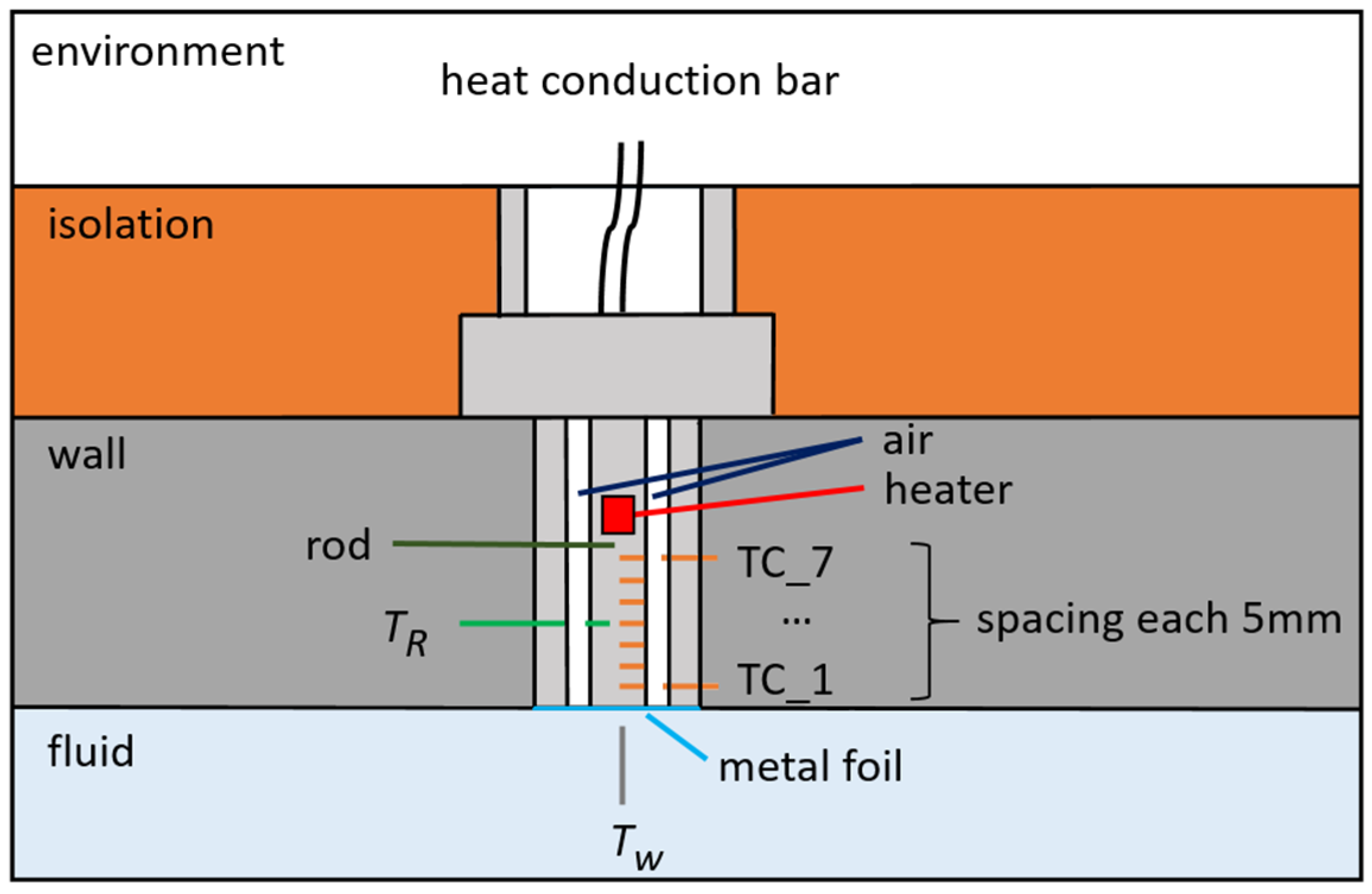

The sensor (

Figure 1) consists primarily of a measuring rod, a foil and the housing. Thereby, the cylindrical rod is equipped with several sensing elements. The diameter of the rod is approximately 8 mm. The foil provides the connection between the rod and the fluid. The sensor housing protects the electronics and establishes thermal contact with the steam turbine casing (wall). Accordingly, the sensor can be considered to be thermally well coupled.

The temperature field of a casing of a steam turbine can be highly inhomogeneous. This effect may be caused by steam extraction or injection, geometric asymmetries in the casing or operation at partial load, which results in the presence of hot circulating flow patterns. Additionally, heat fluxes are superimposed in all directions.

The measuring rod is surrounded by insulating air, enabling the measurement of only the wall-normal (quasi radial) heat flux. Therefore, heat flows in the axial or circumferential direction can be eliminated by design. The only possible heat transfer from the rod to the sensor housing is via heat radiation, which is negligible due to the small temperature differences involved.

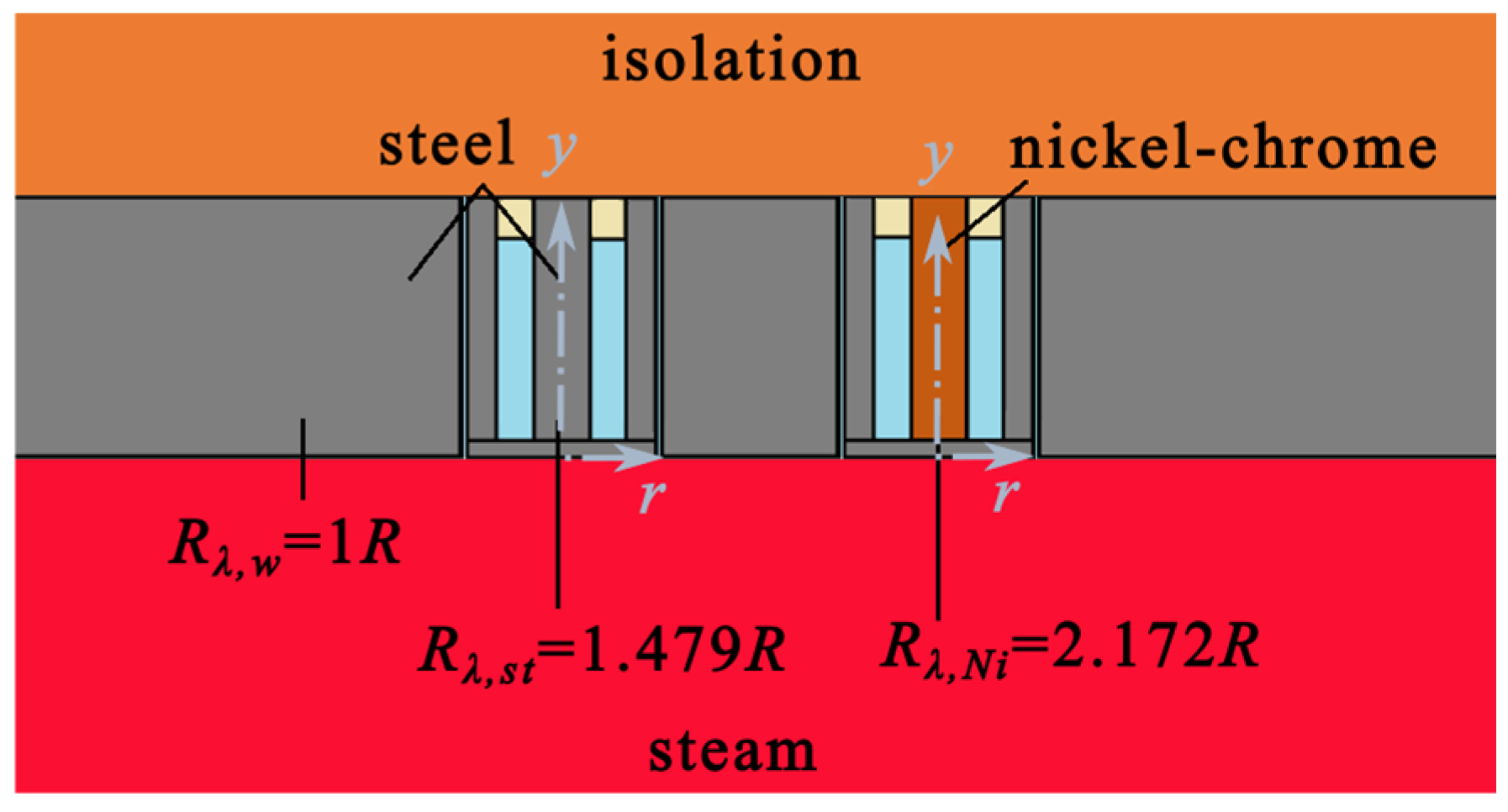

Seven thermocouples (indicated in orange) are positioned on the rod. Notably, one of these is used as the cold junction. It is installed in the centre of the thermocouples (θ3). By using a resistance thermometer, one temperature and six differential temperatures can be measured. This architecture enables the measurement of very low thermoelectric voltages. High amplification and comprehensive protection of the signals ensure high measurement resolution with low noise.

For this type of proprietary thermocouple, the Seebeck coefficient must be determined individually for this specific material pairing selected. Standard turbine steel was used as rod material in this work. This corresponds approximately to the types of thermocouples E and J. These types are characterised by excellent thermoelectric properties, resulting in high transmission factors. The sensor design and the determination of the transmission factor are described in detail in [

24]. Thereby, the transmission factors were determined at different reference temperatures.

Another component is the heating unit, which allows for manipulation of the temperature field.

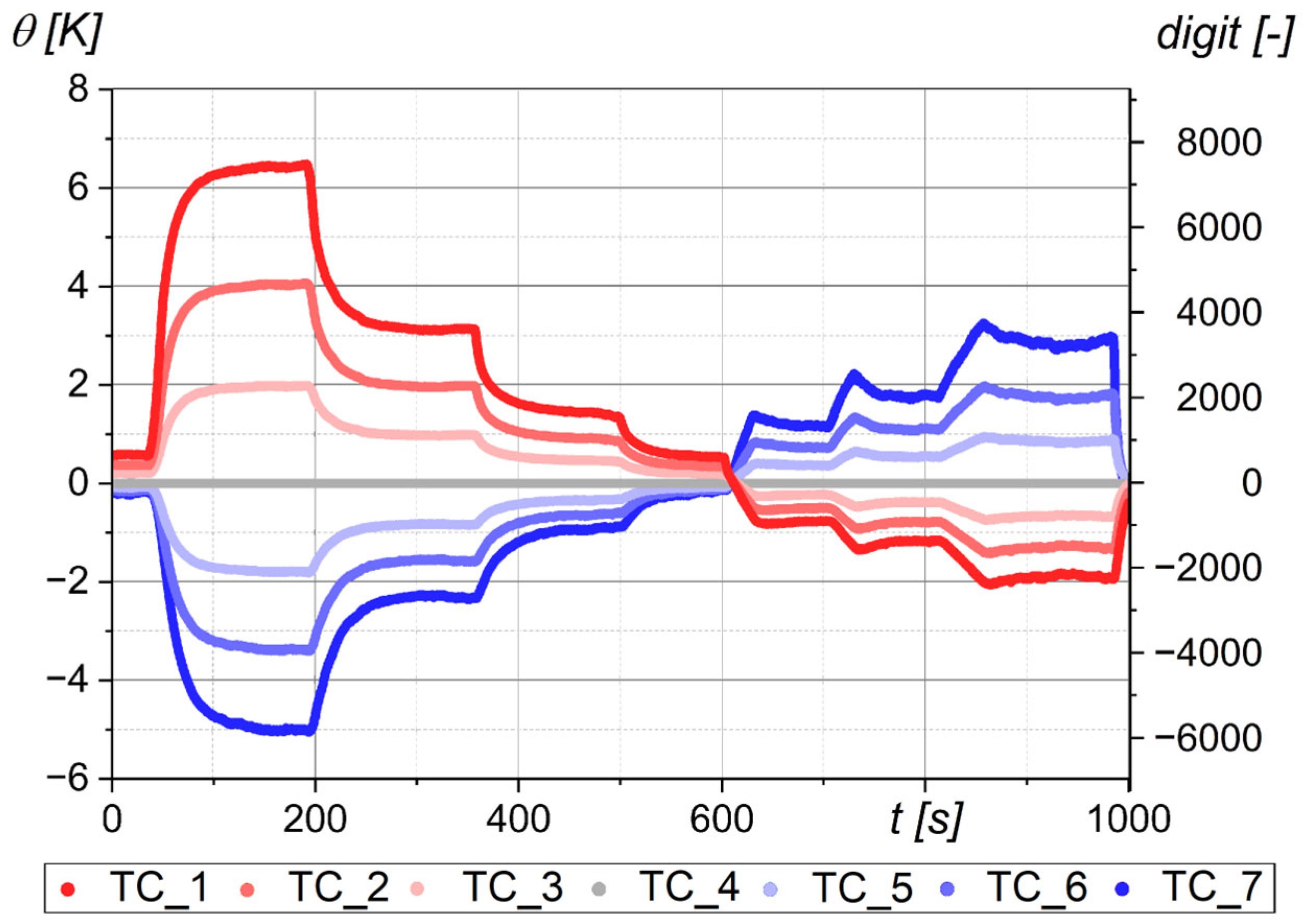

Figure 2 presents the time plot of the differential temperatures relative to the cold junction at the centre. Heat fluxes were applied to each of the rod ends. It can be observed that the heat fluxes across the rod are reversed. Consequently, heat fluxes can be measured validly in both directions. The resolution is comparatively high, exceeding 1000 digit/K for steel and exceeding 600 digit/K for nickel–chrome, with low scattering. The sampling rate was approximately 5 Hz.

Using this heating component and a specialised measurement technique, it is possible to measure the adiabatic wall temperature [

24]. This method is consistent with those reported in the literature. Pinilla et al. [

26] determined adiabatic wall temperatures on turbine vanes using small, double-layered thin film gauges. Laveau et al. [

27] investigated a vane passage gap using an infrared camera. The results are presented in relation to CFD calculations. Finally, Lavagnoli et al. [

28] described potential errors that can occur during the determination of adiabatic wall temperatures.

4. Results

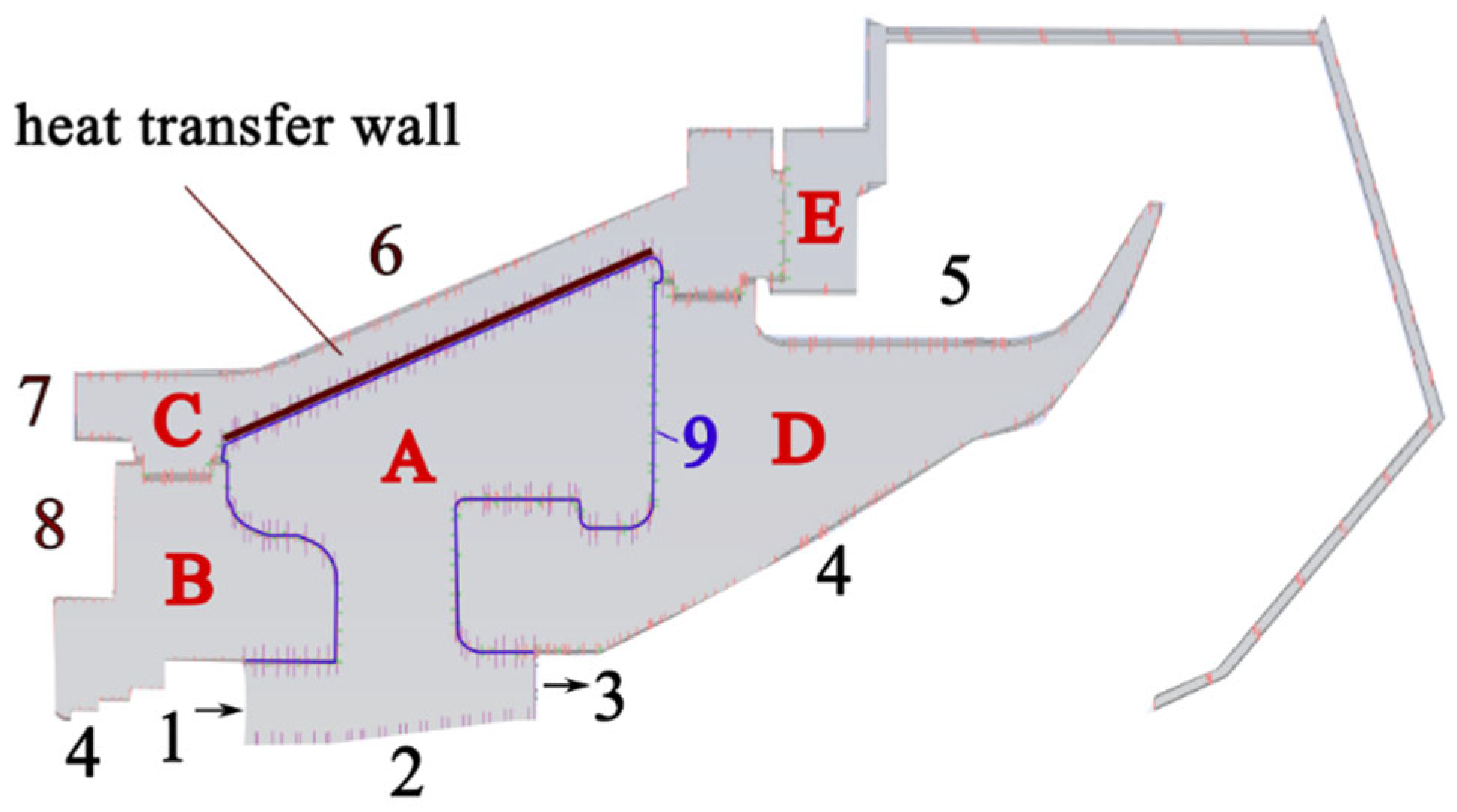

4.1. Temperature Distribution

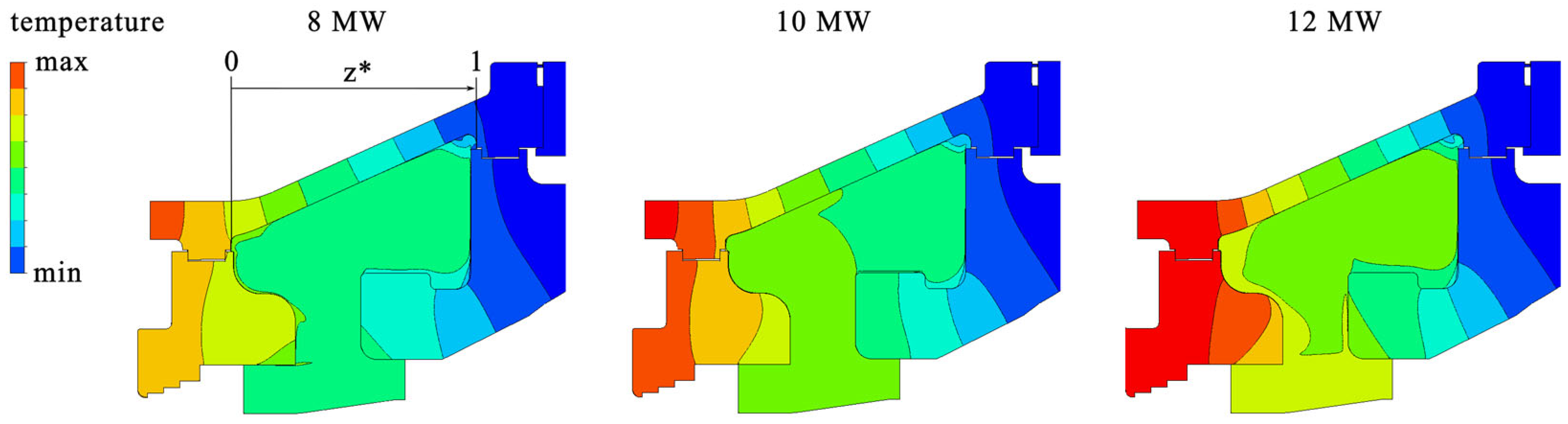

The temperature field of the casing is mainly characterised by an axial and a radial gradient across the machine, as

Figure 8 shows. The axial gradient originates from the live steam valve and the high-pressure turbine, extending to the exhaust steam casing. Thereby the gradient along a guide vane carrier is larger compared to the gradient along a side space, as a larger temperature difference must be reduced within a shorter axial length. Furthermore, heat transfer on the inner side is influenced by the flow regime within the respective side space.

Figure 8 illustrates the temperature distribution at three operating points. It is evident that the temperatures increase with higher machine power. The average temperature in the fluid domain exhibits a similar increase.

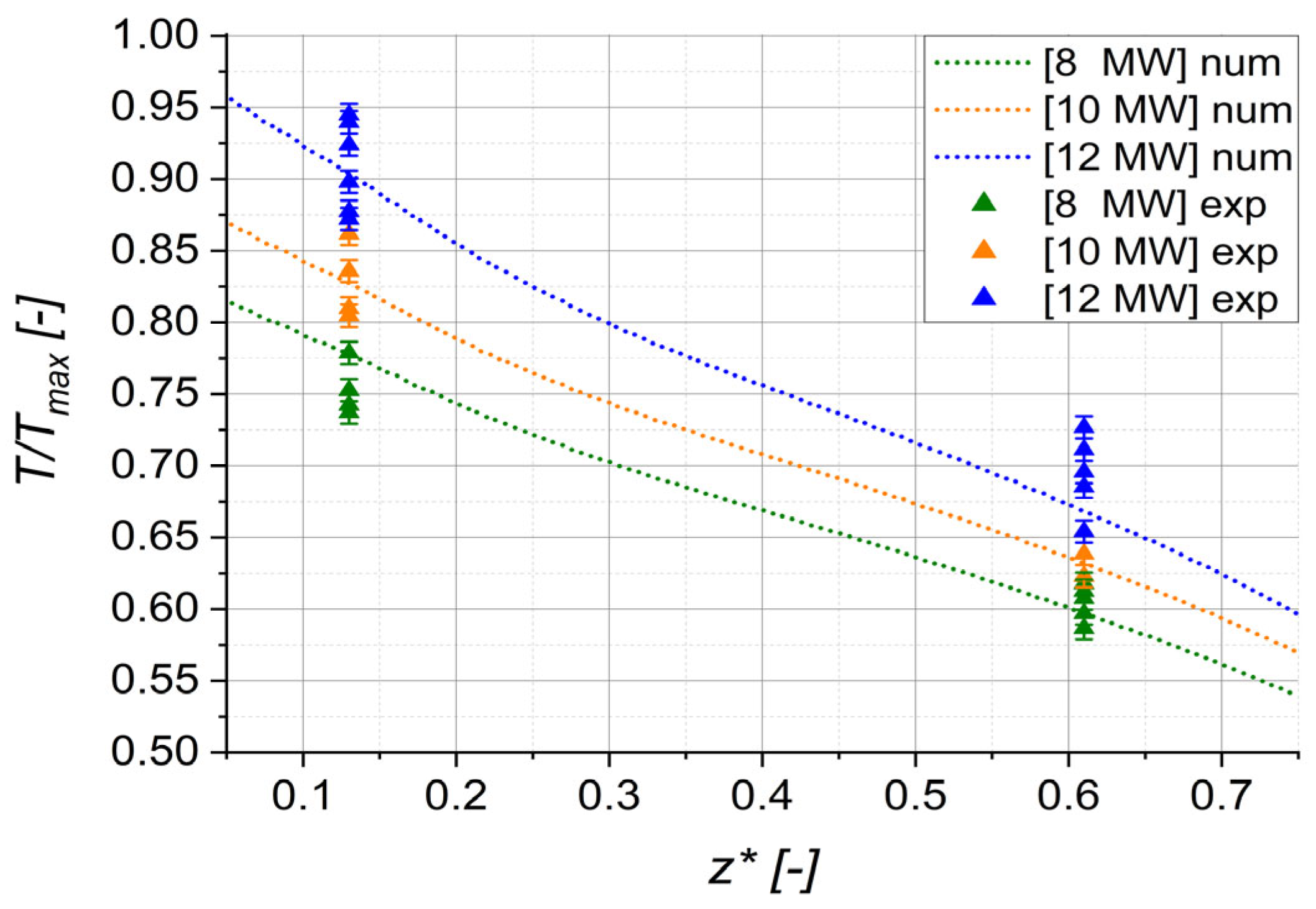

The temperature in the heat transfer wall was calculated numerically and measured. Both results are shown in

Figure 9. All temperatures were referenced to a maximum temperature,

Tmax, which represents the highest temperature observed. This procedure was also applied to the other physical variables. The numerical model shows good agreement with the measurement data. However, the measured data exhibit some scatter, even when accounting for the error bars. This variation can be attributed, on the one hand, to the duration of the machine’s operation on the respective measurement day at the given operating point. On the other hand, it is important to consider whether the operating point was reached from a lower or higher starting point. This affects whether the components were already warmed up or still required time to reach the operating temperature. In conclusion, the measured and calculated data are in good agreement.

4.2. Velocity Field

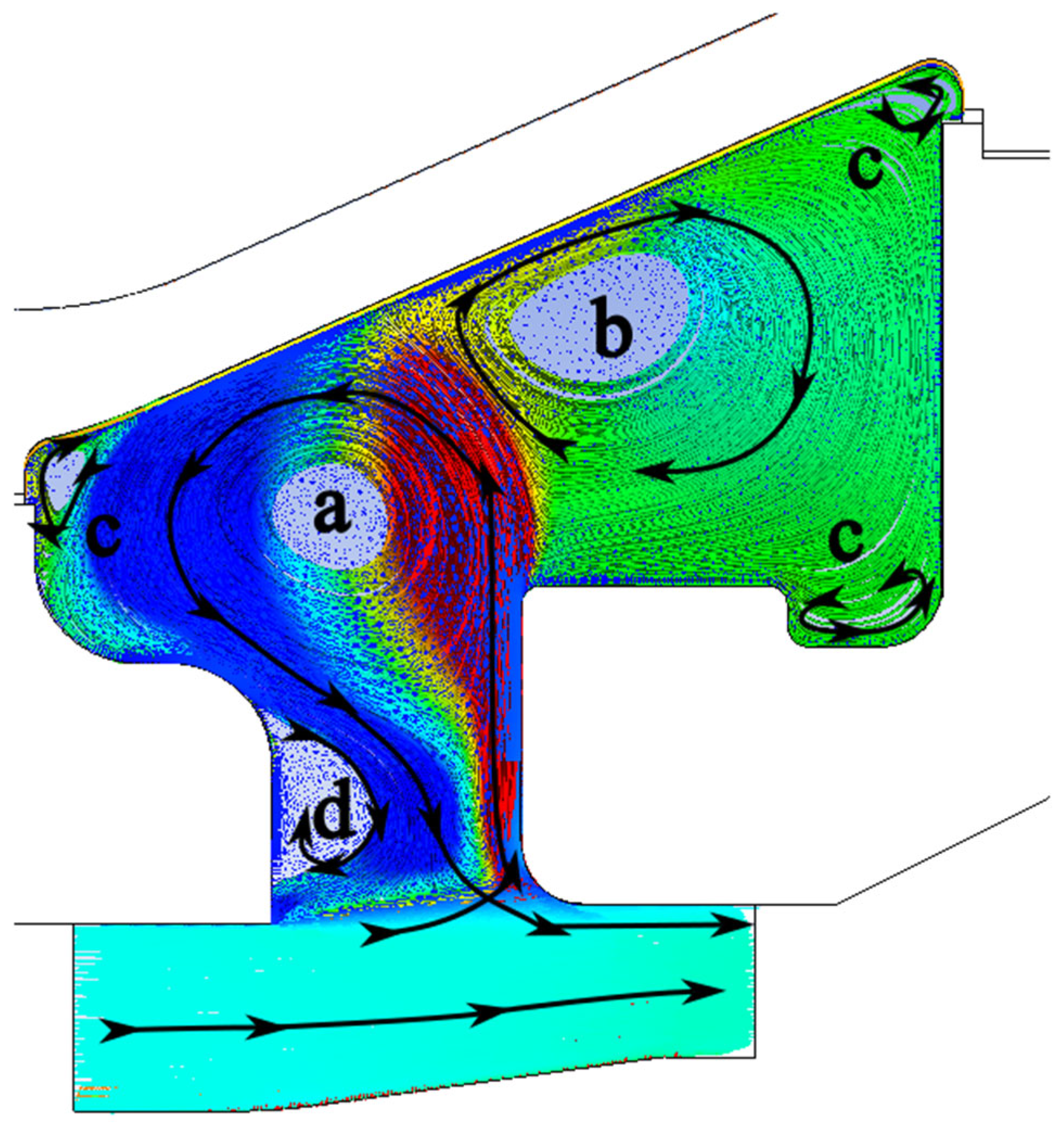

The velocity field can be divided into different regions with different effects. This is visualised using streamlines, as shown in

Figure 10, where red indicates positive radial velocity and blue regions correspond to negative radial velocity. Basically, the fluid domain can be divided into two areas. These are the fraction of the flow that passes through the main flow path. It is characterised by high, almost straight, predominantly axial velocity. Here, the fluid elements only remain in the computational domain for a very short time. The other fraction represents the flow within the side space, or secondary flow, which exhibits complex flow dynamics.

The flow structure in the side space is driven by flow fraction, which is colliding with the end face of the guide vane carrier 3 (

Figure 6, component D). Consequently, the flow is deflected radially outward. A radial impingement jet flow is developed, impacting an inclined wall. This leads to the formation of two dominant, poloidal main vortices, located to the left and right of the stagnation point (

Figure 10, vortex a and b). The front vortex (a) rotates anti-clockwise, while the rear vortex (b) rotates in the opposite direction. The centre of the rotation of the latter is closer to the exhaust casing. Additionally, smaller, counter-rotating vortices (with reversed vorticity) form in the corner areas (

Figure 10, vortices c). A detachment (

Figure 10, vortex d) occurs in the radially lower area of the vane carrier 2 (

Figure 6, component B), just before the fluid elements leave the side space to the main flow. A counter-rotating vortex is located in this area.

The entire flow regime is superimposed with a swirl rotating around the rotor axis (i.e., in circumferential direction), known as toroidal vortex. Due to different operating points and differently developed swirl, either the poloidal or the toroidal vortex components presumably dominate, overlap and influence each other. However, the influence of the swirl will not be discussed in detail in this paper.

The lateral velocity near the wall, and consequently the wall shear stress at the heat transfer wall, reaches a local maximum near the stagnation point. Due to the continuous enthalpy flow of the impingement jet, the fluid and the wall reach approximately the same temperature at this point. The wall cannot absorb or dissipate heat quickly and therefore remains at the flow temperature. The temperature increases upstream (towards the intermediate pressure section) and decreases downstream.

In relation to the flow velocity, the casing is hotter than the fluid from the stagnation point towards the intermediate pressure section. As a result, the casing heats the medium in this area, and heat flows from the casing wall to the fluid. The reverse occurs downstream of the stagnation point, where the casing is cooler than the steam. Consequently, the steam heats the wall in these areas. This leads to a change in the algebraic sign of the heat flux, which is also accompanied by a change in the sign of the temperature difference, .

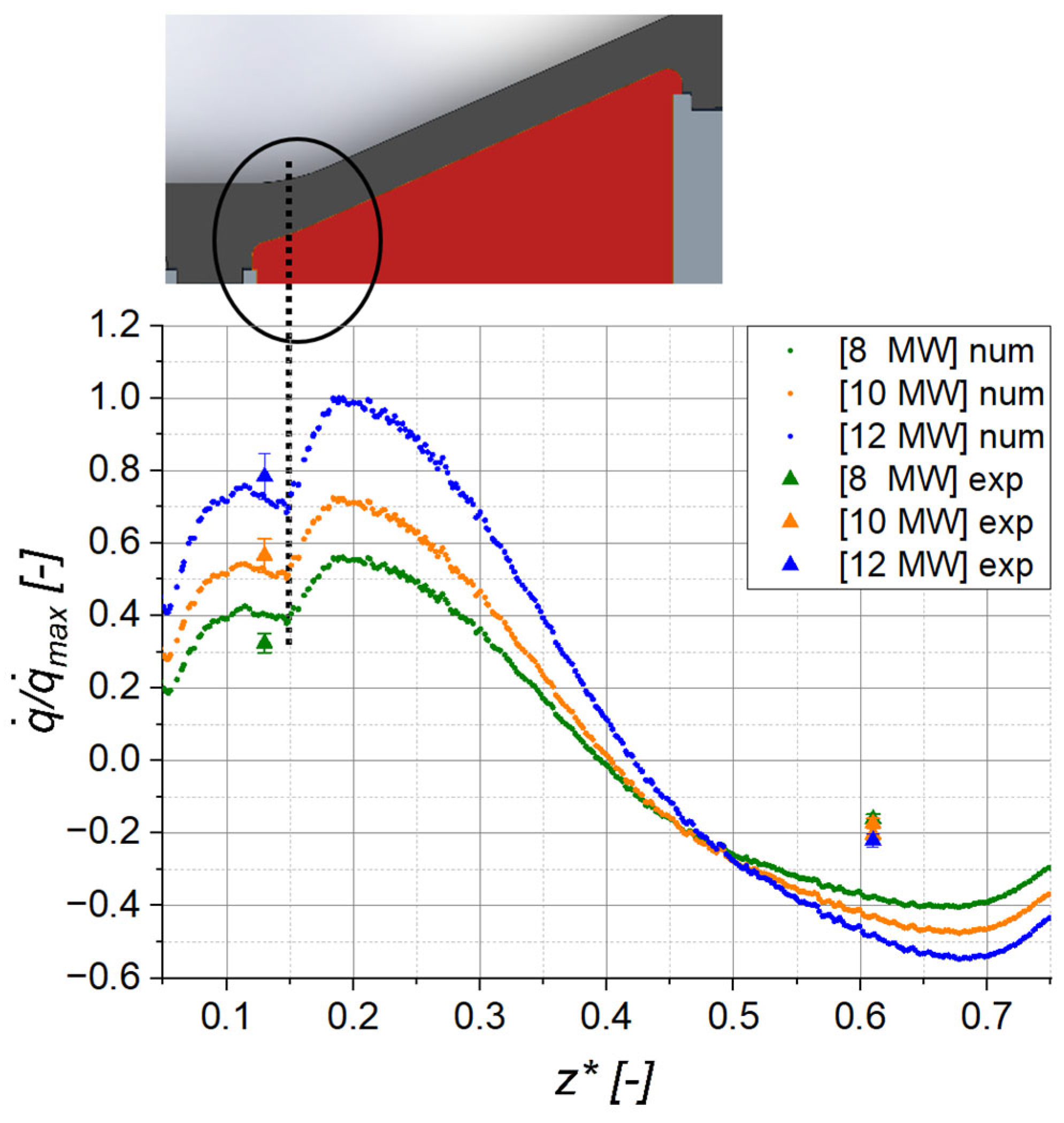

4.3. Heat Flux

Figure 11 illustrates the distribution of heat flux on the heat transfer wall in relation to the dimensionless axial coordinate

z*. Positive heat fluxes were measured and calculated for

z* < 0.42 (12 MW). A positive value indicates that the heat flux is directed from the wall to the fluid, meaning that heat is being transferred into the control volume of the fluid domain. The authors are not aware of any work that has measured heat flux from the wall to the fluid within a steam turbine casing. For 0.42 <

z* (12 MW), the heat flux becomes negative, indicating that heat is transferred from the fluid to the colder wall. At

z* = 0.15, a discontinuity in the heat flux curve can be observed. This discontinuity is attributed to a change in the geometry of the casing, where the transition from a predominantly cylindrical body to a cone begins. This transition is realised through a rounding with a large radius.

The negative wall heat fluxes at z* = 0.61 are slightly overestimated by the numerical model used. This discrepancy may arise from the fact that the heat dissipated by the exhaust steam casing is likely underestimated in the model, or from the inability of the flow regime—particularly the swirl—to accurately reproduce heat transfer at this point at the solid–fluid interface.

Nevertheless, there is good agreement between the experimental data and the numerical calculations. Based on the simulations, a distribution of the heat flux across the entire heat transfer wall can be predicted, which is corroborated by the good agreement between the measured and calculated casing temperatures.

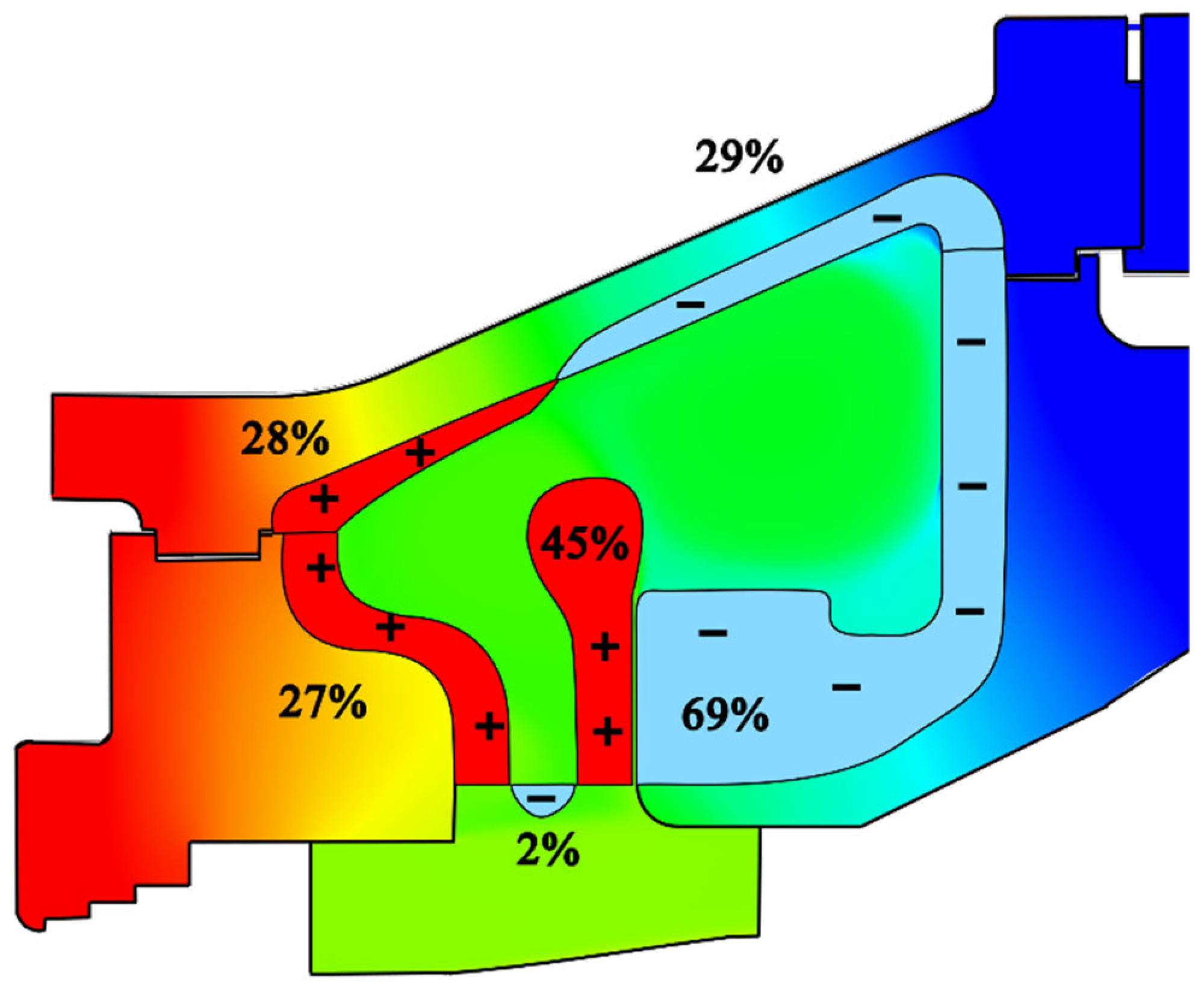

4.4. Energy Balance

In order to develop an approach for modelling the development of the heat flux across the boundaries of the fluid domain, an energy balance was considered. The boundary was located along the fluid–solid interface and was closed by a horizontal area at the inlet of the side space. It was found that there are three sections along the boundary that contribute heat to this domain and three sections that remove heat from it. In addition, dissipative heat energy occurs inside the fluid due to internal friction. However, this effect can be neglected due to its negligible influence. Considering the magnitude of the heat quantities, the dissipative heat component is very small.

Figure 12 shows the six different regions and illustrates the heat-affected zones. The fraction that contributes heat is considered first. The majority (45%) is introduced through the flow entering the side space. Twenty-eight percent is added by the front part of the heat transfer wall (

Figure 6, component C). The remaining portion, approximately one-quarter (27%), is contributed via guide vane carrier 2 (

Figure 6, component B).

The heat-absorbing regions are as follows: 69 % of the heat exits the investigated area through vane carrier 3 (

Figure 6, component D). A further 29% is transmitted to the rear part of the casing (

Figure 6, component C). Only 2% exits the control volume in the form of escaping steam.

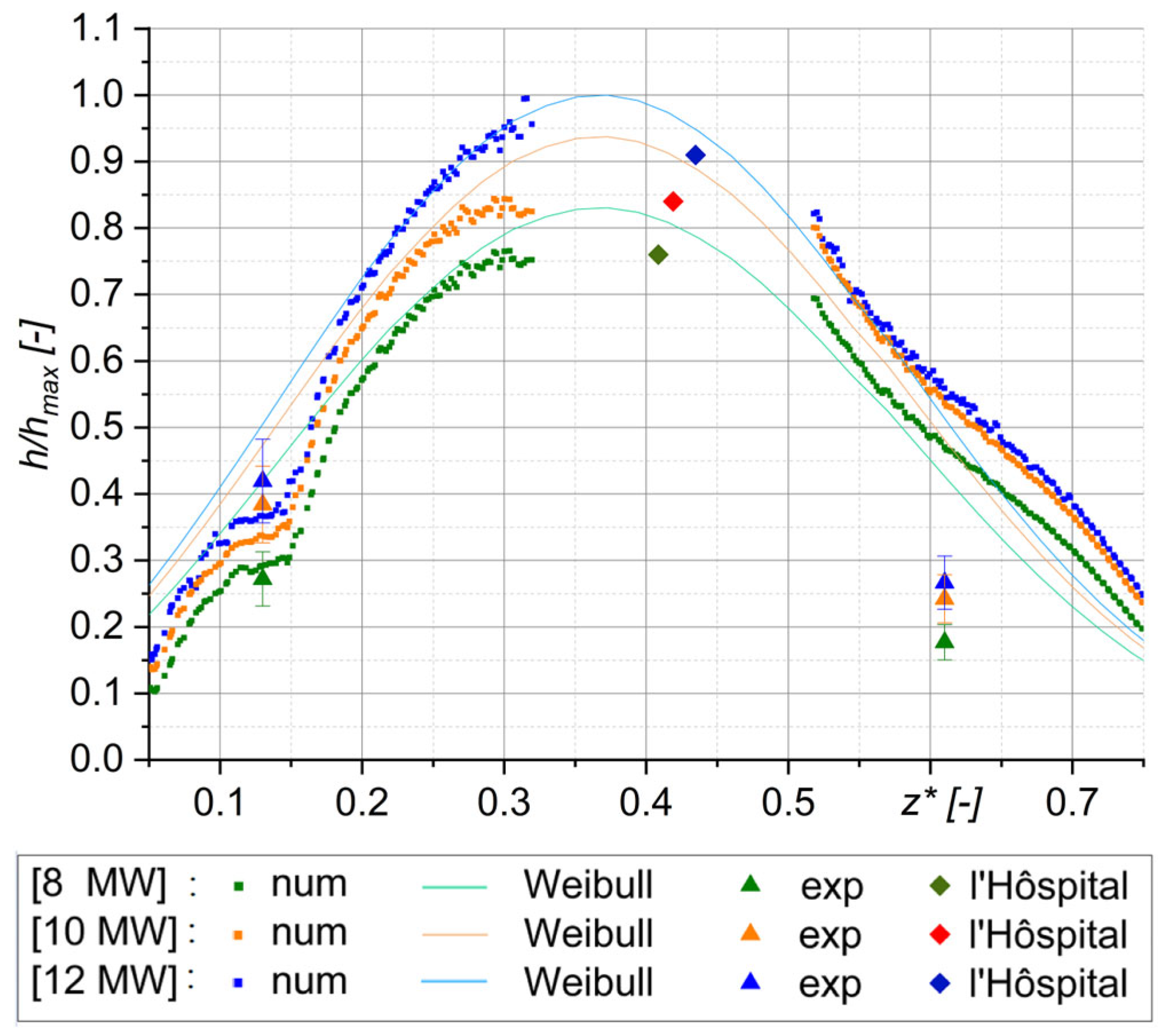

4.5. Heat Transfer Coefficient

By using Equation (3), the local heat transfer coefficient can be calculated. Here, the local heat flux and the local wall temperature, and the volumetrically averaged fluid temperature of domain A (

Figure 6) are used.

The result is shown in

Figure 13. The following colour code is as in the previous diagrams: 8 MW—green, 10 MW—orange, 12 MW—blue. The experimental results are represented by triangles, the numerical calculation by squares, the approximated function based on the numerical calculation as a line, and the results from l’Hôspital as diamonds. The approximated function is similar to a skewed Gaussian distribution. A Weibull distribution was chosen for the approximation. All required fits were approximated using least squares with the programme OriginPro (version 2023b 64-bit SR1).

The numerical values between 0.275 and 0.525 are omitted. This is due to the existence of specific points

z0* along the wall, where temperature ∆

T → 0 and heat flux

→ 0 tend towards zero. According to Equation (3), a singularity arises at this point. Therefore, the numerical results develop to ±∞, depending on the sign. This effect makes the results unreliable in this area. This situation corresponds to one of l’Hôspital’s rules, specifically the case “0/0”. Consequently, the limit value can be analysed. For this purpose, the functions of

and

were approximated, inserted into Equation (4), and the limit value

considered. Polynomial functions were used for this purpose. Regarding the heat flux, sine functions can also be applied. If this procedure does not yield a reliable result, the derivatives of the functions can also be used. However, in such cases, a reliable outcome is not always guaranteed, but it may still lead to the desired result, as in

Figure 13.

An approximation was performed for the progression of the numerical values. For this purpose, the Weibull function was used. The resulting fit demonstrates a sufficiently good agreement. This applies to both the numerical calculations, and the results from the l’Hôpital limit evaluation.

At the end, the following results are obtained.

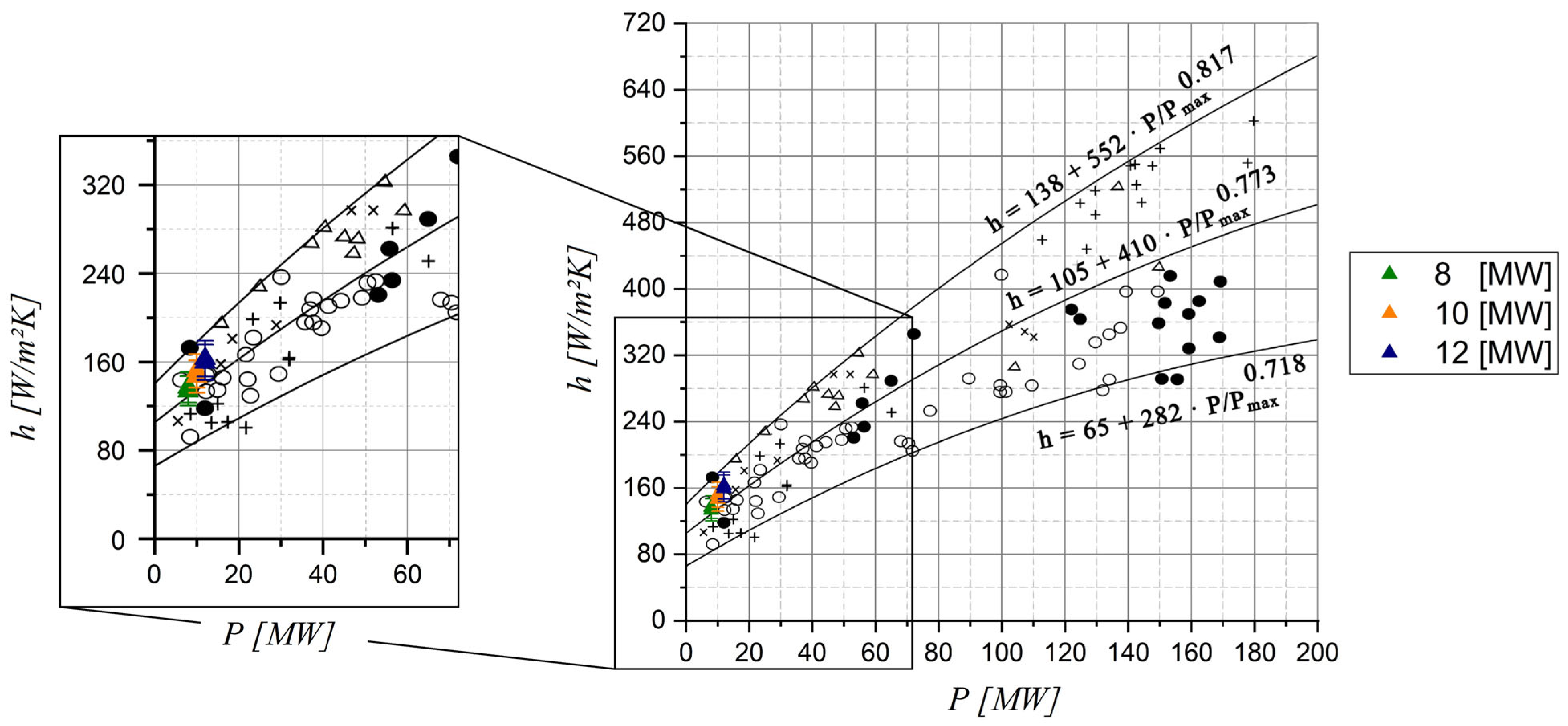

Finally, the peak values of the heat transfer coefficient are compared with the results from the literature [

10,

19]. It can be demonstrated that the results align with the mean measured values (

Figure 14).

5. Conclusions and Outlook

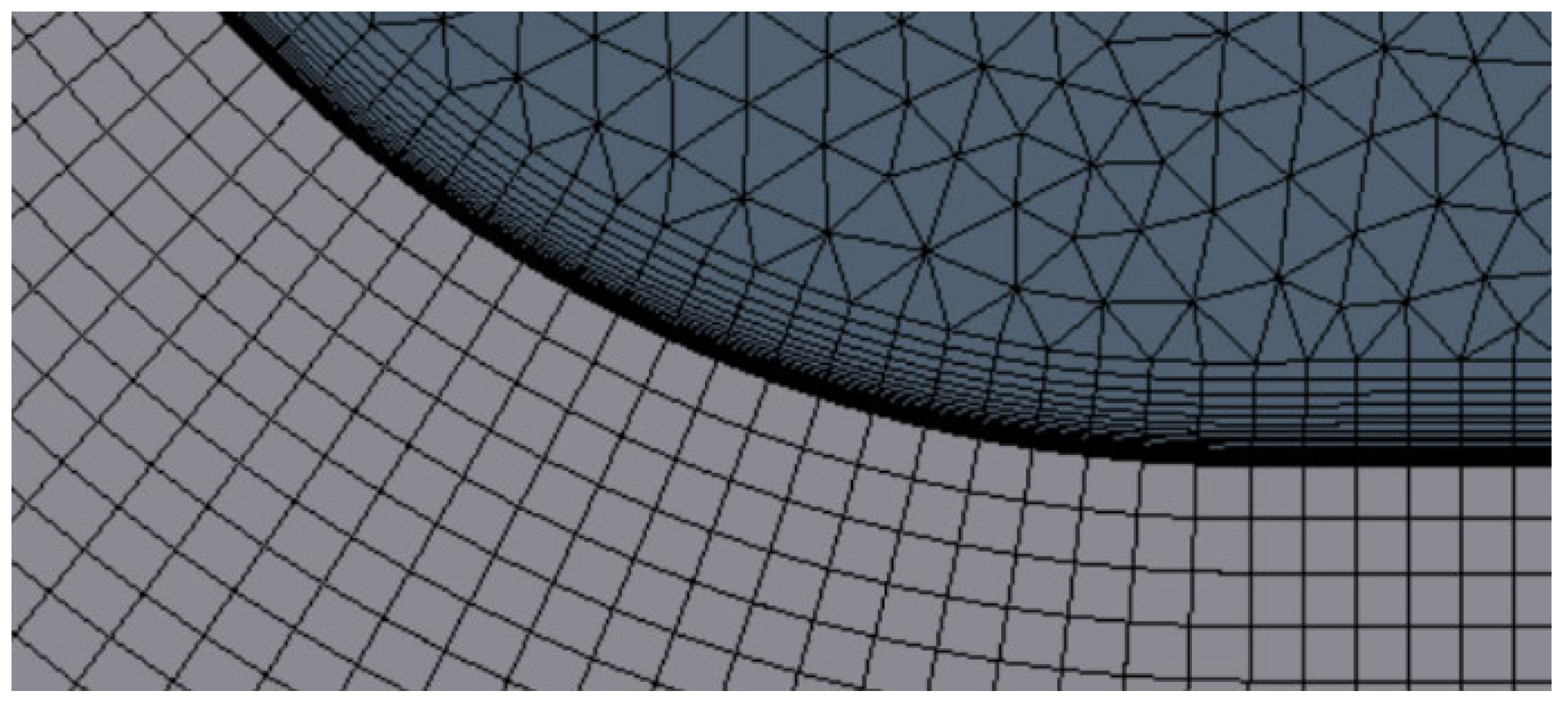

A new sensor for measuring heat transfer onto a steam turbine casing was designed, calibrated, validated and deployed for measurements in a 12 MW full-scale steam turbine. The primary focus was on thermal measurement in a side space, which was complemented by numerical investigations. A numerical study of the mesh quality was conducted, and the boundary conditions for the respective regions were defined based on measurement data. One of the key outcomes is the temperature distribution on the outer casing of the steam turbine. Data from temperature measurement and numerical simulations yielded identical values. The velocity field was presented and discussed in relation to different flow regimes. Visualisation through streamlines illustrated two dominant vortices. Their effects on the boundary layer near the wall significantly influence heat transfer. Furthermore, both the measured and numerically calculated heat fluxes perpendicular to the wall were presented. A directional change in the heat flux along the axial component was observed. It may be the first time a wall heat flux has been measured within a steam turbine casing, transferring heat from the wall to the fluid. The results for the heat transfer coefficient were also presented for both experimental and numerical data. Additionally, a l’Hôpital analysis was conducted, and a correlation for the distribution of the heat transfer coefficient was developed using a function that describes a skewed Gaussian distribution. Overall, the Weibull distribution provided an excellent approximation for this purpose. The heat transfer coefficient was compared with values from the literature. Finally, the results corroborate findings from other scientific studies. This enhanced understanding will contribute to more accurate numerical boundary conditions and improve the quality of the results. Given the scarcity of studies and measurement data on heat transport in side spaces of steam turbines, the results are of significant scientific importance.

Building on the presented work, the analysis of heat transfer in steam turbines, particularly in side spaces, will be systematically advanced. Sensitive factors with a significant impact must be identified and further analysed.