Mixed Methods Evaluation of a Youth-Friendly Clinic for Young People Living with HIV Transitioning from Pediatric Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview

2.2. Setting

2.3. Participants/Recruitment

2.4. Quantitative Data Collection Procedures

2.5. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.6. Qualitative Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of Sample

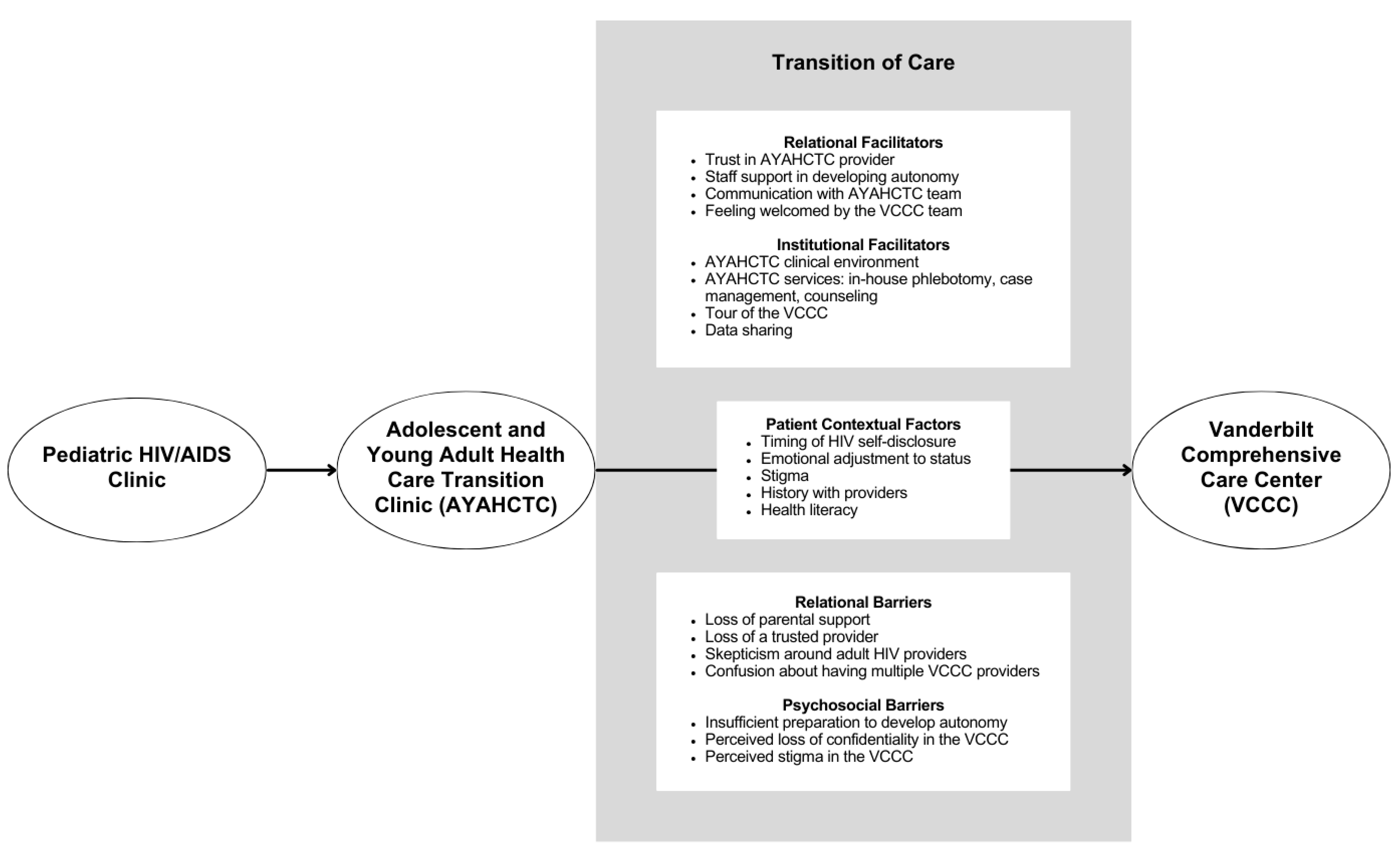

3.2. Framework for Patients’ Perceptions of Factors Affecting Transition from Adolescent to Adult Care

3.3. Major Themes

3.3.1. Theme 1: Patient Contextual Factors

3.3.2. Theme 2: Transition of Care Facilitators

Relational Facilitators

Institutional Facilitators

3.3.3. Theme 3: Transition of Care Barriers

Relational Barriers

4. Discussion

4.1. Patient-Identified Barriers to Transition of Care

4.2. Patient-Identified Facilitators to Transition of Care

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV Incidence and Prevalence in the United States, 2017–2021; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC HIV in the South Issue Brief; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019.

- Ginossar, T.; Oetzel, J.; Van Meter, L.; Gans, A.A.; Gallant, J.E. The Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program after the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act full implementation: A critical review of predictions, evidence, and future directions. Top. Antivir. Med. 2019, 27, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pettit, A.C.; Pichon, L.C.; Ahonkhai, A.A.; Robinson, C.; Randolph, B.; Gaur, A.; Stubbs, A.; Summers, N.A.; Truss, K.; Brantley, M.; et al. Comprehensive Process Mapping and Qualitative Interviews to Inform Implementation of Rapid Linkage to HIV Care Programs in a Mid-Sized Urban Setting in the Southern United States. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2022, 90, S56–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adimora, A.A.; Ramirez, C.; Schoenbach, V.J.; Cohen, M.S. Policies and politics that promote HIV infection in the Southern United States. AIDS 2014, 28, 1393–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownstein, P.S.; Gillespie, S.E.; Leong, T.; Chahroudi, A.; Chakraborty, R.; Camacho-Gonzalez, A.F. The Association of Uncontrolled HIV Infection and Other Sexually Transmitted Infections in Metropolitan Atlanta Youth. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2015, 34, e119–e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fair, C.; Albright, J. “Don’t Tell Him You Have HIV Unless He’s ‘The One’”: Romantic Relationships Among Adolescents and Young Adults with Perinatal HIV Infection. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2012, 26, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, A.H.; Hazra, R. The changing epidemiology of the global paediatric HIV epidemic: Keeping track of perinatally HIV-infected adolescents. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2013, 16, 18555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E.R.; Beste, S.; Barr, E.; Wallace, J.; McFarland, E.J.; Abzug, M.J.; Darrow, J.; Melvin, A. Health Outcomes of International HIV-infected Adoptees in the US. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2016, 35, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slogrove, A.L.; Mahy, M.; Armstrong, A.; Davies, M.-A. Living and dying to be counted: What we know about the epidemiology of the global adolescent HIV epidemic. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Continisio, G.I.; Lo Vecchio, A.; Basile, F.W.; Russo, C.; Cotugno, M.R.; Palmiero, G.; Storace, C.; Mango, C.; Guarino, A.; Bruzzese, E. The Transition of Care From Pediatric to Adult Health-Care Services of Vertically HIV-Infected Adolescents: A Pilot Study. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryscavage, P.; Herbert, L.; Roberts, B.; Cain, J.; Lovelace, S.; Houck, D.; Tepper, V. Stepping up: Retention in HIV care within an integrated health care transition program. AIDS Care 2022, 34, 554–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njuguna, I.N.; Beima-Sofie, K.; Mburu, C.W.; Mugo, C.; Itindi, J.; Onyango, A.; Neary, J.; Richardson, B.A.; Oyiengo, L.; Wamalwa, D.; et al. Transition to independent care for youth living with HIV: A cluster randomised clinical trial. Lancet HIV 2022, 9, e828–e837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturo, D.; Powell, A.; Major-Wilson, H.; Sanchez, K.; De Santis, J.P.; Friedman, L.B. Transitioning Adolescents and Young Adults With HIV Infection to Adult Care: Pilot Testing the “Movin’ Out” Transitioning Protocol. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2015, 30, e29–e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straub, D.M.; Tanner, A.E. Health-care transition from adolescent to adult services for young people with HIV. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveras, C.; Cluver, L.; Bernays, S.; Armstrong, A. Nothing About Us Without RIGHTS-Meaningful Engagement of Children and Youth: From Research Prioritization to Clinical Trials, Implementation Science, and Policy. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2018, 78 (Suppl. 1), S27–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.; Hill, S.V.; Alexander, K.A.; Ahonkhai, A.A.; Ameyan, W.; Hatane, L.; Zanoni, B.C.; D’Angelo, L.; Friedman, L.; Cluver, L. Improving Outcomes for Adolescents and Young Adults Living With HIV. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 73, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.; Agwu, A.L.; Castelnouvo, B.; Trent, M.; Kambugu, A.D. Improved retention in care for Ugandan youth living with HIV utilizing a youth-targeted clinic at entry to adult care: Outcomes and implications for a transition model. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoni, B.C.; Archary, M.; Sibaya, T.; Musinguzi, N.; Kelley, M.E.; McManus, S.; Haberer, J.E. Development and validation of the HIV adolescent readiness for transition scale (HARTS) in South Africa. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2021, 24, e25767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reif, S.S.; Sullivan, K.; Wilson, E.; Berger, M.; McAllaster, C. HIV/AIDS Care and Prevention Infrastructure in the US Deep South. Available online: https://southernaidsstrategy.org/infrastructure/ (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Zuniga, M.A.; Buchanan, R.J.; Chakravorty, B.J. HIV education, prevention, and outreach programs in rural areas of the southeastern United States. J. HIV/AIDS Soc. Serv. 2006, 4, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding the HIV Care Continuum; US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Volume 4.

- Gonzalez, J.S.; Penedo, F.J.; Antoni, M.H.; Durán, R.E.; McPherson-Baker, S.; Ironson, G.; Isabel Fernandez, M.; Klimas, N.G.; Fletcher, M.A.; Schneiderman, N. Social support, positive states of mind, and HIV treatment adherence in men and women living with HIV/AIDS. Health Psychol. 2004, 23, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R. The Provisions of Social Relationships; Rubin, Z., Ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1974; pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona, C.E.; Russell, D.W. The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. Adv. Pers. Relatsh. 1987, 1, 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- Reinius, M.; Wettergren, L.; Wiklander, M.; Svedhem, V.; Ekström, A.M.; Eriksson, L.E. Development of a 12-item short version of the HIV stigma scale. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, G.S.; Lukens-Bull, K.; Yin, X.; Demars, N.; Huang, I.-C.; Livingood, W.; Reiss, J.; Wood, D. Measuring the Transition Readiness of Youth with Special Healthcare Needs: Validation of the TRAQ—Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2009, 36, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjora, A. Qualitative Research as Stepwise-Deductive Induction; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Azungah, T. Qualitative research: Deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis. Qual. Res. J. 2018, 18, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoletta, K.M.; Starr, S.R. Health systems science. Adv. Pediatr. 2021, 68, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehman, B.J.; David, D.M.; Gruber, J.A. Rethinking the biopsychosocial model of health: Understanding health as a dynamic system. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2017, 11, e12328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramonti, F.; Giorgi, F.; Fanali, A. Systems thinking and the biopsychosocial approach: A multilevel framework for patient-centred care. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2021, 38, 215–230. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV; United States Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- Rowe, K.; Buivydaite, R.; Heinsohn, T.; Rahimzadeh, M.; Wagner, R.G.; Scerif, G.; Stein, A. Executive function in HIV-affected children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analyses. AIDS Care 2021, 33, 833–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvie, P.A.; Brummel, S.S.; Allison, S.M.; Malee, K.M.; Mellins, C.A.; Wilkins, M.L.; Harris, L.L.; Patton, E.D.; Chernoff, M.C.; Rutstein, R.M.; et al. Roles of Medication Responsibility, Executive and Adaptive Functioning in Adherence for Children and Adolescents With Perinatally Acquired HIV. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2017, 36, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, K.S.; Beima-Sofie, K.M.; Moraa, H.; Wagner, A.D.; Mugo, C.; Mutiti, P.M.; Wamalwa, D.; Bukusi, D.; John-Stewart, G.C.; Slyker, J.A. “At our age, we would like to do things the way we want:” a qualitative study of adolescent HIV testing services in Kenya. Aids 2017, 31, S213–S220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidman, R.; Violari, A. Growing up positive: Adolescent HIV disclosure to sexual partners and others. AIDS Care 2020, 32, 1565–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, G.Z.; Reinius, M.; Eriksson, L.E.; Svedhem, V.; Esfahani, F.M.; Deuba, K.; Rao, D.; Lyatuu, G.W.; Giovenco, D.; Ekström, A.M. Stigma reduction interventions in people living with HIV to improve health-related quality of life. Lancet HIV 2020, 7, e129–e140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, M.L.S.; Darmont, M.Q.R.; Monteiro, S.S. HIV-related stigma among young people living with HIV transitioning to an adult clinic in a public hospital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Cien Saude Colet. 2021, 26, 2653–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fair, C.D.; Berk, M. Provider perceptions of stigma and discrimination experienced by adolescents and young adults with pHiV while accessing sexual and reproductive health care. AIDS Care 2018, 30, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabunya, P.; Byansi, W.; Sensoy Bahar, O.; McKay, M.; Ssewamala, F.M.; Damulira, C. Factors Associated With HIV Disclosure and HIV-Related Stigma Among Adolescents Living With HIV in Southwestern Uganda. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan-Blitz, L.T.; Mena, L.A.; Mayer, K.H. The ongoing HIV epidemic in American youth: Challenges and opportunities. Mhealth 2021, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naswa, S.; Marfatia, Y.S. Adolescent HIV/AIDS: Issues and challenges. Indian J. Sex. Transm. Dis. AIDS 2010, 31, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, K.S.; Bauermeister, J.A.; Zimmerman, M.A. Psychological Distress, Substance Use, and HIV/STI Risk Behaviors Among Youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010, 39, 514–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitahi-Kamau, N.; Wahome, S.; Memiah, P.; Bukusi, E.A. The Role of Self-Efficacy in HIV treatment Adherence and its interaction with psychosocial factors among HIV Positive Adolescents in Transition to Adult Care in Kenya. Vulnerable Child. Youth Stud. 2022, 17, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela, J.M.; Buchanan, C.L.; Radcliffe, J.; Ambrose, C.; Hawkins, L.A.; Tanney, M.; Rudy, B.J. Transition to Adult Services among Behaviorally Infected Adolescents with HIV—A Qualitative Study. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2009, 36, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fair, C.D.; Sullivan, K.; Dizney, R.; Stackpole, A. “It’s like losing a part of my family”: Transition expectations of adolescents living with perinatally acquired HIV and their guardians. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012, 26, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philbin, M.M.; Tanner, A.E.; Chambers, B.D.; Ma, A.; Ware, S.; Lee, S.; Fortenberry, J.D.; The Adolescent Trials, N. Transitioning HIV-infected adolescents to adult care at 14 clinics across the United States: Using adolescent and adult providers’ insights to create multi-level solutions to address transition barriers. AIDS Care 2017, 29, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.; Jin, L.; Childs, J.; Posada, R.; Jao, J.; Agwu, A. Outcomes of a Comprehensive Retention Strategy for Youth With HIV After Transfer to Adult Care in the United States. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2019, 38, 722–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantrell, K.; Patel, N.; Mandrell, B.; Grissom, S. Pediatric HIV disclosure: A process-oriented framework. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2013, 25, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guideline on HIV Disclosure Counselling for Children Up to 12 Years of Age; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sherr, L.; Cluver, L.D.; Toska, E.; He, E. Differing psychological vulnerabilities among behaviourally and perinatally HIV infected adolescents in South Africa—Implications for targeted health service provision. AIDS Care 2018, 30, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mburu, G.; Hodgson, I.; Kalibala, S.; Haamujompa, C.; Cataldo, F.; Lowenthal, E.D.; Ross, D. Adolescent HIV disclosure in Zambia: Barriers, facilitators and outcomes. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2014, 17, 18866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoni, B.C.; Archary, M.; Subramony, T.; Sibaya, T.; Psaros, C.; Haberer, J.E. Disclosure, Social Support, and Mental Health are Modifiable Factors Affecting Engagement in Care of Perinatally-HIV Infected Adolescents: A Qualitative Dyadic Analysis. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Patient and Family Engagement in Primary Care. Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/reports/engage/interventions/index.html (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Tanner, A.E.; Philbin, M.M.; Ma, A.; Chambers, B.D.; Nichols, S.; Lee, S.; Fortenberry, J.D.; Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. Adolescent to Adult HIV Health Care Transition From the Perspective of Adult Providers in the United States. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momplaisir, F.; McGlonn, K.; Grabill, M.; Moahi, K.; Nkwihoreze, H.; Knowles, K.; Laguerre, R.; Dowshen, N.; Hussen, S.A.; Tanner, A.E.; et al. Strategies to improve outcomes of youth experiencing healthcare transition from pediatric to adult HIV care in a large U.S. city. Arch. Public Health 2023, 81, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, A.E.; Dowshen, N.; Philbin, M.M.; Rulison, K.L.; Camacho-Gonzalez, A.; Lee, S.; Moore, S.J.; Fortenberry, J.D.; Hussen, S.A. An Intervention for the Transition From Pediatric or Adolescent to Adult-Oriented HIV Care: Protocol for the Development and Pilot Implementation of iTransition. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2021, 10, e24565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, M.; Archary, M.; Adong, J.; Haberer, J.E.; Kuhns, L.M.; Kurth, A.; Ronen, K.; Lightfoot, M.; Inwani, I.; John-Stewart, G.; et al. Systematic Review of mHealth Interventions for Adolescent and Young Adult HIV Prevention and the Adolescent HIV Continuum of Care in Low to Middle Income Countries. AIDS Behav. 2023, 27, 94–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agwu, A.L.; Yusuf, H.E.; D’Angelo, L.; Rathore, M.; Marchesi, J.; Rowell, J.; Smith, R.; Toppins, J.; Trexler, C.; Carr, R.; et al. Recruitment of Youth Living With HIV to Optimize Adherence and Virologic Suppression: Testing the Design of Technology-Based Community Health Nursing to Improve Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) Clinical Trials. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2020, 9, e23480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, A.E.; Philbin, M.M.; DuVal, A.; Ellen, J.; Kapogiannis, B.; Fortenberry, J.D. Transitioning HIV-Positive Adolescents to Adult Care: Lessons Learned From Twelve Adolescent Medicine Clinics. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2016, 31, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, V.; Wong, M.; Rodriguez, C.A.; Sanchez, H.; Galea, J.; Ramos, A.; Senador, L.; Kolevic, L.; Matos, E.; Sanchez, E.; et al. Community-based accompaniment for adolescents transitioning to adult HIV care in urban Peru: A pilot study. AIDS Behav. 2022, 26, 3991–4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, J.T.; Wong, M.; Ninesling, B.; Ramos, A.; Senador, L.; Sanchez, H.; Kolevic, L.; Matos, E.; Sanchez, E.; Errea, R.A.; et al. Patient and provider perceptions of a community-based accompaniment intervention for adolescents transitioning to adult HIV care in urban Peru: A qualitative analysis. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2022, 25, e26019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, R.; Adetunji, A.; Kuhns, L.M.; Omigbodun, O.; Johnson, A.K.; Kuti, K.; Awolude, O.A.; Berzins, B.; Janulis, P.; Okonkwor, O.; et al. Evaluation of the iCARE Nigeria Pilot Intervention Using Social Media and Peer Navigation to Promote HIV Testing and Linkage to Care Among High-Risk Young Men: A Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e220148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, D.; Hrapcak, S.; Ameyan, W.; Lovich, R.; Ronan, A.; Schmitz, K.; Hatane, L. Peer Support for Adolescents and Young People Living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: Emerging Insights and a Methodological Agenda. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019, 16, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.; Snyder, J.; Dell, S.; Nolan, K.; Keruly, J.; Agwu, A. Impact of a Youth-Focused Care Model on Retention and Virologic Suppression Among Young Adults With HIV Cared for in an Adult HIV Clinic. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2019, 80, e41–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Eligible AYAHCTC Patients (n = 21) | Interviewed Patients (n = 5) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 33.33% | 0% |

| Male | 66.66% | 100% |

| Gender Identity | ||

| Cisgender identity | 100% | 100% |

| Heterosexual | 71.4% | 60% |

| Bisexual | 14.3% | 20% |

| Homosexual | 14.3% | 20% |

| Race and Ethnicity | ||

| Black race | 85.7% | 100% |

| Caucasian race | 9.5% | 0% |

| Asian race | 4.8% | 0% |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0% | 0% |

| International Identity | ||

| Internationally born | 47.6% | 40% |

| International adoptee | 22.2% | 20% |

| Primary Language | ||

| English | 90.5% | 100% |

| Non-English | 9.5% | 0% |

| Insurance Status | ||

| Private | 61.9% | 80% |

| Medicaid | 38.1% | 20% |

| HIV Transmission Group | ||

| Non-perinatal | 28.6% | 20% |

| Perinatal | 71.4% | 80% |

| Number of Patients | 21 |

|---|---|

| Mean age at 1st visit (years) | 19.6 |

| Average time in clinic (years) | 2.21 |

| Average number of visits | 7.86 |

| Visits per year (# visits/duration in clinic) | 4.34 |

| Engagement in first year (%) | 100.0% |

| Retention in first year (%) | 95.5% |

| Viral suppression at first visit (%) | 66.7% |

| Viral suppression at last visit (%) | 81.0% |

| Number of patients who transitioned out of AYAHCTC | 11 |

| Mean, SD | |

|---|---|

| Social Provision Scale | 14.1 +/− 2.0 |

| HIV Stigma Scale | 6.7 +/− 3.7 |

| Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire | 4.3 +/− 0.7 |

| PHQ-9 | 2.0 +/− 1.2 |

| Subthemes: Patient Contextual Factors | Selected Exemplary Quotes |

|---|---|

| Timing of HIV self-disclosure | I’ve always been taking medication […] I never knew why I was taking medication, until I turned maybe 10 and that’s when they told me. So, at that point, it was just like, “Okay.” It was never really a struggle living with HIV. […] It was just something I lived with. |

| [Time of disclosure] would have been around eight or nine years of age. | |

| Emotional adjustment to HIV status | It took years. It was just years of conversation from the adolescent clinic, from my provider that was at my children’s hospital. […] And when I say years, years, not two or three, this is like 10 years of conversations trying to get the guts and the courage to sit and talk about [my HIV status] and stop leaving it sitting in on me and it stressing me out. And it’s a lot of build up, anger and stuff like that. |

| Stigma | I don’t like saying [HIV], so you got to, excuse me. I’ll probably say ‘it’ or ‘status’. I guess dealing with that status, you kind of wonder if some people are really nice because they feel bad or they’re just being nice because they’re nice people. But I always like to think that they would be nice because they’re nice people, and that’s how I look at it. |

| Just feeling like an outcast. | |

| History with providers | I still keep in touch with [Dr. NAME at AYAHCTC] […] Very friendly staff, physicians very friendly, just makes you feel like you don’t have HIV to begin with. |

| Health literacy | The [laboratory] results, I personally don’t ever really check on until I go back to the office […] there’s a lot of things that I don’t want to worry myself about and they’re actually normal. So, I don’t even bother looking at my test results on my own, but I know that if I were, [Dr. NAME] is going to explain them to me, he’s going to explain them very thoroughly, he’s going to make an action plan with me right then and right there. |

| Facilitator | Exemplary Quote |

|---|---|

| Trust in AYAHCTC provider | And then the adolescents, [Dr. NAME at AYAHCTC] already knew [Dr. NAME at VCCC]. So, the fact that the two communicated made me more accepting of the transition. |

| Staff support in developing autonomy | My parents used to schedule all the appointments for me, but now before fully transitioning, [my providers] basically taught me, ‘Hey, you need to start doing this’, gave a little more responsibility, a real small step until I was fully able to do appointments by myself, order prescriptions myself. So, they slowly over a couple months or so were like ‘Hey, I’m going to start slowly not doing things for you’, and you slowly start picking up your own medication, which I got used to really quickly. And after that I was like, okay, I’ve been doing this for quite a while, I know what to do now. |

| Communication with AYAHCTC team | If I need something after the appointment that I forgot to talk to [Dr. NAME] about, I can ask my nurse and they’ll go get him. Or if he’s in another patient’s room, he’ll tell me, “Well, text me on the telehealth app” […] He’s always there. |

| [Front desk staff] are always quick to respond. Even if they don’t answer, they may call me back in, I would say the longest probably was maybe an hour they’ll be calling back, but 9 times out of 10, they answer the phone. | |

| In the adolescent workup, yes, they prepared me for the next step, be like, ‘Hey, for the next step you’ll have to do X, Y, Z by yourself with little help from your parents’, which mentally prepared me like, okay, this is all for me and my health matters to me and my parents can intervene if need be, but this is all for me. So, it helped me get ready. | |

| Feeling welcomed by the VCCC team | I met the physician that was going to be helping or taking care of me. I met the caseworkers, case managers, the front desk people. And it was more of a relief that everybody was very friendly towards [Dr. NAME from AYAHCTC] and they knew the whole situation. So, I guess it was relieving, not too scary. |

| AYAHCTC clinical environment | Whenever I walk in most doctors’ offices, dental offices, most places in the healthcare industry, they’re really overworked and overwhelmed at times, and you can definitely tell by the way that they greet you. It’s like they’re trying to get you in and out very quickly. With my adolescent clinic, I don’t really feel that way. I feel like whenever I’m walking in, they’re excited to see me. |

| And I don’t feel like there’s judgment whenever I’m in [the waiting room], people are not staring at me. They don’t know why I’m going there because, I mean, it’s just an adolescent clinic, so it’s not like no one knows, oh, he has HIV or, oh, he’s done this, he’s done that. No, there’s not that pre-assumed, what’s the word, pre-assumed notion on a person. It’s just very calming, and I just feel like that’s where I should be. | |

| It could be intimidating to be in that [examination] room, and they make it less of that and more of a chill and comfort while doing the examination. | |

| I did like how every room has a privacy curtain. That was nice. Because I didn’t always feel like at any given moment, somebody could walk in, and I’d be exposed. | |

| In-house phlebotomy | [The laboratory technologists] were very friendly. They were very, very good. They did their job quite well. And if I had a curious thought about why, what was the blood for, what’s the purpose of me getting the blood draw, they would tell me to get sample of this diagnosis, whatnot, and I’ll be at ease at that moment knowing that. |

| [The phlebotomy room] is very comfortable. It’s very good. It gives distraction. When you look at the wall, you see various creatures, drawings on the wall. It’s a very chill environment. I like that. | |

| So, from pediatrics and adolescents, usually they have their own little spot for labs. When I went to the adult care clinic, I had to go to another spot for labs, which other people had to get labs. So, I was just used to being in and out. You do the examination, you do the lab in the same place, and then you’re out. And adults, it’s like you do the examination and you have to go downstairs and get your labs. And the labs, the waiting room or waiting area might take 40 min to wait. | |

| Case management or healthcare navigator service | The [caseworker] gave me her card the first time I met her. She was like, “If you need anything, don’t hesitate. Call and let me know and we’ll figure it out together, or if I have to do some researching”. She’s there for her people. She’s not just going to leave you. It’s not the blind leading the blind. |

| The [caseworker] will send me information on insurance policy plans, new prescriptions, and health plans. So, he’ll just keep me updated with new information surrounding about the healthcare of HIV, new medication, new testing that’s going on. He’ll text me at least once a month, making sure I’m good. So, he was a very friendly guy. | |

| My fixing [with HIV] was going to be within myself as far as getting comfortable with it […] rather than, “Hey, I want you to meet such and such, they’re going to be your case worker for the day”. And then they talk about it and it’s like, I don’t even know who you are. You haven’t been around. And I’m not even comfortable with telling close people. How do you know? It just didn’t feel comfortable for me to talk to them. | |

| Counseling service | She was one who done kind of a little evaluation on me, and she was like, “You may be a little depressed. Do you want to go see someone?” And she was recommending all of these places for me to go and all of these people for me to see. […] I really do like that. It’s very sweet of her. |

| I tried counseling, realized it was not for me. I didn’t like talking to people that hadn’t been through the same things and understood exactly what I was going through. It just felt very weird, and in a way, I felt a little judged going to someone. | |

| Tour of the VCCC | [Dr. NAME] set up a whole tour with somebody who was in the adult care […] Let me get to know the people who are in the adult clinic, so the transition would be a little bit easier. So that was very helpful to me, as far as getting to know where I’m going, how it looks, instead of just being pushed into the unknown. |

| Data sharing | They already knew who I was and stuff when I got there […] I guess they transferred my file or something, but I don’t know. |

| Barrier | Exemplary Quote |

|---|---|

| Loss of parental support | It was when I went to my first appointment by myself […] It was weird in a way since I’ve been only going with my parents and whatnot, so it was all up to me to listen and get the information and process it and choose the next option. So, I was usually the one to sit back and twiddle my thumbs while the parents talked to the doctor. But now just I was forced […] to listen and hear instead of playing around. |

| Loss of a trusted provider | For me, it’s not the fact that I have to transfer, it’s more so the fact that I have to have a new doctor, and I feel like I’ve built a bond with [Dr. NAME] already, and that what we have going on is something that’s working for us. And I really like that he’s starting to understand me, I’m starting to understand his expectations a lot more, and he just cares about his patients, so I want to see him [at the adult clinic]. My biggest challenge was switching physicians because like I said, at the time I was happy where I was at, happy with my care, built a really close relationship with my physicians and stuff like that. So, it’s always hard to leave when you build a really strong connection with people who are helping you. |

| Skepticism around adult HIV providers | I feel like a lot of adult doctors, they’re just there just to examine you and go on about their day. I like the conversations that me and [Dr. NAME] have, because sometimes I do go in there nervous, because I have very bad anxiety that I’m trying to work on, and he understands that. So, he talks to me, he explains everything. I feel like I’m not going to get that at other places at all. |

| Confusion about having multiple VCCC providers | [Dr. NAME at AYAHCTC] has my personal number, so we communicate through there. […] They’re switching out my [adult care] physician, so I never know what new physician I have. It’s usually on MyHealth. |

| Insufficient preparation to develop autonomy | I guess the beginning of the adult [care] […] just taught me you are responsible for your health and not anyone else. And that came as a shock in a way because I always relied on others to make choices for my health, but the fact that I’m in charge of making it is scary. In that small transition of adolescence to adult, it would’ve helped to learn how to reschedule things yourself and or set time for appointment. |

| Loss of confidentiality in the VCCC | When I was a kid, it was okay because everybody was in [AYAHCTC] for different reasons. But as an adult, it’s just kind of like, I don’t know, very uncomfortable because [VCCC is] in a whole separate part of the building, and it’s isolated. […] And everybody’s in there for the same thing. So, I feel like that takes the privacy away. So, I didn’t like that part. And that’s what took me so long to get out of the children’s part. |

| Perceived stigma in the VCCC | But with the VCCC, you go in there and I went to school with this person and there’s no other reason for you to be checking in over here but for that and I don’t know, it just felt weird. Now it’s one of those things where rumors can start, people accidentally saying something, “Oh, I seen such… How did you see him when you…” So, all that, it’s just so uncomfortable. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chew, H.; Bonnet, K.; Schlundt, D.; Hill, N.; Pierce, L.; Ahonkhai, A.; Desai, N. Mixed Methods Evaluation of a Youth-Friendly Clinic for Young People Living with HIV Transitioning from Pediatric Care. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9090198

Chew H, Bonnet K, Schlundt D, Hill N, Pierce L, Ahonkhai A, Desai N. Mixed Methods Evaluation of a Youth-Friendly Clinic for Young People Living with HIV Transitioning from Pediatric Care. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2024; 9(9):198. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9090198

Chicago/Turabian StyleChew, Hannah, Kemberlee Bonnet, David Schlundt, Nina Hill, Leslie Pierce, Aima Ahonkhai, and Neerav Desai. 2024. "Mixed Methods Evaluation of a Youth-Friendly Clinic for Young People Living with HIV Transitioning from Pediatric Care" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 9, no. 9: 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9090198

APA StyleChew, H., Bonnet, K., Schlundt, D., Hill, N., Pierce, L., Ahonkhai, A., & Desai, N. (2024). Mixed Methods Evaluation of a Youth-Friendly Clinic for Young People Living with HIV Transitioning from Pediatric Care. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 9(9), 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed9090198