Epidemiological Differences in Hajj-Acquired Airborne Infections in Pilgrims Arriving from Low and Middle-Income versus High-Income Countries: A Systematised Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

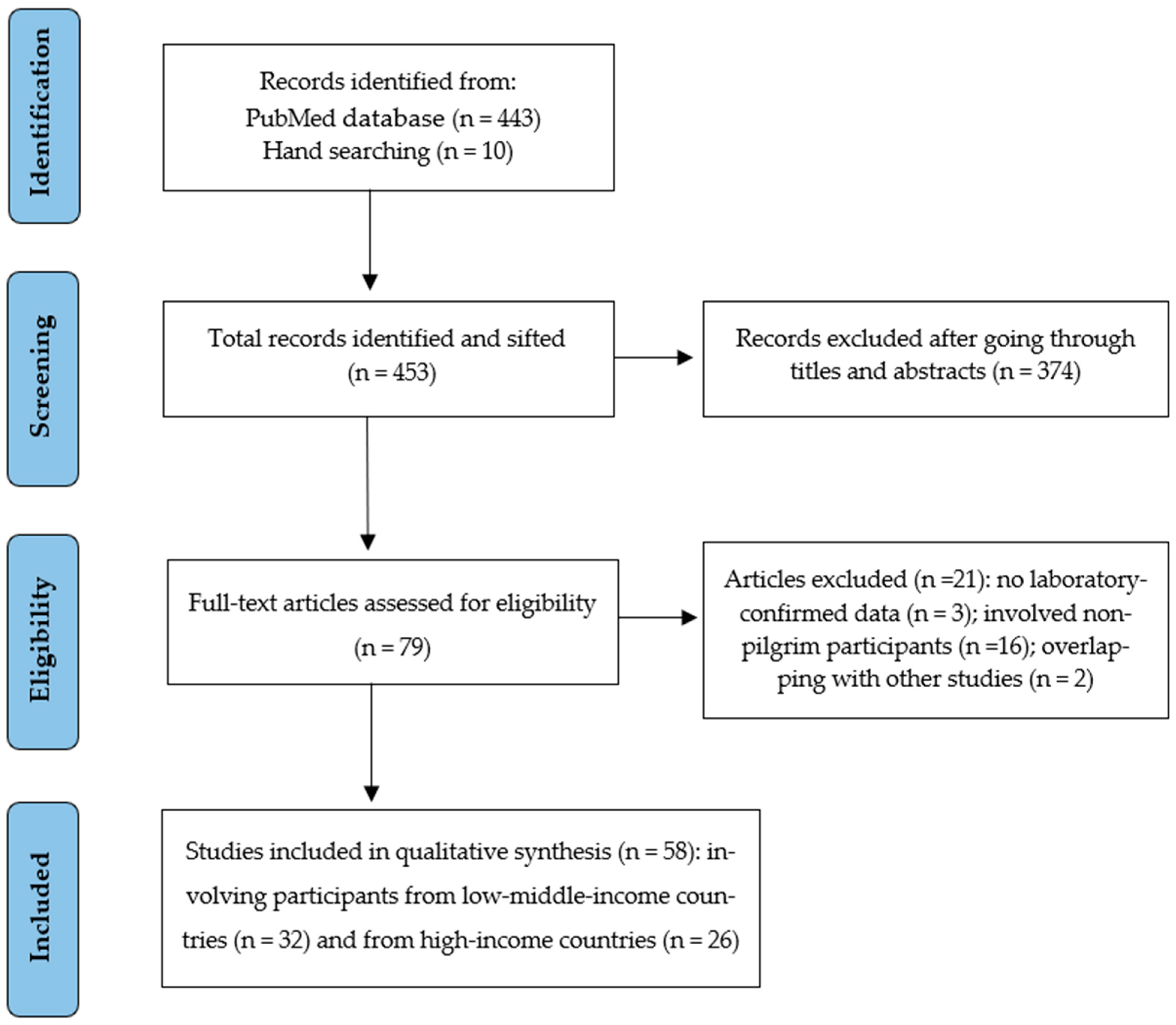

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

2.2. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. General Description of Included Studies and Quality Assessment

| Author, Publication Year | Study Year | Participants’ Nationalities (%) | Selection Method/Case Ascertainment | Testing Method | Sample Size | Mean/Median Age (Range) | Male: Female | Risk Factors (%) | Vaccine Uptake (%) | Detected Diseases Name | Disease Burden n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlBarrak et al., 2018 [13] | 2016 | Majority from LMIC: Indonesian (22.3) Egyptian (10.2) Indian (9.8) | Adults with radiologically confirmed pneumonia admitted in general hospitals in Makkah and Al Madinah | Urine antigen test was used in addition to culture-based methods | 266 | 65.3 (30–90) | 2:1 | Diabetes (36) | NR | Community-acquired pneumonia | S. pneumoniae 48 (18) |

| Alborzi et al., 2009 [41] | 2006–2007 | Iranian | Pilgrims with symptoms of ARI at Shiraz airport on return from the Hajj | Direct fluorescent staining and viral culture were performed on nasal wash specimens. Rhinovirus and enterovirus tested by RT-PCR | 255 | 52.4 (19–82) | 1:1.1 | NR | Influenza vaccine (85.5) | Viral respiratory infections | Influenza 25 (9.8) Rhinovirus 15 (5.9) Other viruses 42 (16.4) |

| Alsayed et al., 2021 [14] | 2019 | Asian (64) African (30.3) European (2.7) North American (2.2) Oceanian (0.5) | Pilgrims with severe ARI symptoms who were initially hospitalised at seven healthcare facilities in Makkah, Arafat, and Mina at Hajj | Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected and tested using multiplex RT-PCR | 185 | 58 (2 d–88 y) | 1.9:1 | NR | NR | Viral respiratory infections | Rhinovirus 53 (42) Influenza 54 (29.2) Coronaviruses 35 (18.9) Other viruses 19 (10.2) MERS-CoV 0 (0) |

| Alzeer et al., 1998 [32] | 1994 | Middle Eastern (34) South-East Asian (31) Indian (23) African (11) | All pilgrims admitted with pneumonia to Al-Noor Specialist Hospital and King Abdulaziz Hospital, Makkah | Sputum samples or fibre optic bronchoscopy samples for microscopy and culture, blood chemistry | 64 | 63 | 2.6:1 | NR | NR | Pneumonia | Viruses: Influenza 3 (4.7) Parainfluenza 1 (1.6) Bacteria: M. tuberculosis 13 (20.3) S. pneumoniae 6 (9.4) K. pneumoniae 5 (7.8) H. influenzae 3 (4.7) S. aureus 2 (3.1) Other bacteria 11 (17.3) |

| Annan et al., 2015 [42] | 2013 | Ghanaian | Adult pilgrims at the Kotoka International Airport after Hajj | Nasopharyngeal specimens were tested by RT-PCR | 839 | 52 (21–85) | 1:1.2 | NR | NR | Viral respiratory infections | Rhinovirus 141 (16.8) RSV 43 (5.1) Influenza viruses 11 (1.3) MERS-CoV 0 (0) |

| Asghar et al., 2011 [15] | 2005 | Indonesian (18.4) Saudi (17.1) Pakistani (11.8) Indian (9.2) Egyptian (6.6) Malaysian (5.3) Syrian (4) Others (27.6) | Hajj pilgrims with suspected pneumonia who were admitted to hospitals in Makkah | Sputum samples were tested by routine culture, acid fast bacilli examination, and culture | 141 | >94% of cases were >50 y | 1.3:1 | Diabetes (55) | NR | Pneumonia | M. tuberculosis 1 (0.7) S. pneumoniae 5 (3.5) K. pneumoniae 8 (5.7) S. aureus 7 (5) Others 70 (50) |

| Ashshi et al., 2014 [36] | 2010 | 280 Indonesian 157 Algerian 188 Indian 101 Syrian 128 Ivorian 104 Sierra Leonean 113 Somalian 123 Nigerian 112 Turkish 89 Australian 99 American 97 British | Pilgrims entering Saudi Arabia via King Abdulaziz International Airport, Jeddah city | Throat swab analysed using RT-PCR | 1600 | 1309 aged > 40 291 aged ≤ 40 | 1.6:1 | NR | Influenza vaccine (93.4) | Influenza A | Influenza A 120 (7.5) |

| Baharoon et al., 2009 [16] | 2004 | Majority were South Asian | All pilgrims admitted with severe sepsis and septic shock among Hajj pilgrims in two major ICUs in Makkah: King Faisal and King Abdulaziz Hospitals | Clinical diagnosis of severe sepsis/septic shock. Confirmation of source of infection with X-ray and/or positive culture | 42 | 65.4 | 1.8:1 | Lung diseases (71) Hypertension/Cardiac (43) Diabetes (29) Kidney diseases (2) | NR | Bacterial sepsis | Community-acquired pneumonia 23 (54.8) |

| Bokhary et al., 2022 [17] | 2018 | Egyptian (22.3) Sudanese (14.9) Algerian (11.6) Moroccan (9.1) Libyan (2.6) Saudi (14.9) Indian (7.4) Pakistani (6.6) | Adult pilgrims who sought medical care for upper RTIs during Hajj | Oropharyngeal swabs were taken and tested by bacteriological culture method and automated VITEK 2 COMPACT system | 121 | 45 | 8.3:1 | NR | NR | Bacterial respiratory infections | H. influenzae 6 (4.9) S. pneumoniae 2 (1.6) S. aureus 1 (0.8) Others 1 (0.8) |

| El-Gamal et al., 1988 [19] | 1987 | Pakistani, Indian and Indonesian (50) | Suspected cases of meningitis were presented to the outpatient clinic at King Abdulaziz Hospital in Al Madinah city | CSF, blood and skin samples were examined. CSF samples were examined under microscope and by latex test | 229 | (30–70) | 2.3:1 | NR | NR | Meningococcal | Meningitis 188 (82) (177 serogroup A and 11 serogroup C) |

| El-Kafrawy et al., 2022 [20] | 2019 | 15 Indonesian 9 Indian 4 Moroccan 3 Somalian and Sudanese (each) 2 Saudi, Bangladeshi, and Nigerian (each) 13 others | Pilgrims with RTIs who presented to the healthcare facilities at Hajj sites in Makkah | Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected and tested by multiplex RT-PCR | 53 | Majority (58%) >60 years old | NR | NR | NR | Human rhinoviruses | Rhinoviruses 19 (36.8) |

| El-Sheikh et al., 1998 [21] | 1991–1992 | 30 different nationalities | Pilgrims who were referred to either Ajyad hospital or three dispensaries in Jeddah. Upon enrolment, all patients were diagnosed with upper or lower RTIs | Sputa were collected and examined microscopically. Throat swabs were collected for cell culture and virus identification by immunofluorescence | 1156 | (10–80) | NR | NR | NR | Viral and bacterial respiratory infections | Viruses: RSV 18 (2.4) Influenza 49 (6.4) Parainfluenza virus 45 (5.9) Adenovirus 36 (4.7) Bacteria: H. influenzae 42 (10.6) K. pneumoniae 31 (7.8) S. pneumoniae 27 (6.8) S. pyogenes 7 (2.4) S. aureus 11 (3.8) |

| Hashem et al., 2019 [22] | 2014 | Majority Indian and Indonesian | During the 5 days of Hajj, samples were collected from all pilgrims presenting with ARI symptoms and suspected of MERS-CoV infection at seven healthcare facilities in Makkah, Mina, and Arafat | Nasopharyngeal samples were collected and tested using RT-PCR and microarray | 132 | 61.85 (26–95) | 2:1 | NR | NR | Viral respiratory infections | Influenza 39 (29.5) Rhinoviruses 17 (12.1) Coronaviruses 24 (18.2) Other viruses 18 (13.6) MERS-CoV 0 (0) |

| Harimurti et al., 2021 [54] | 2015 | Indonesian | A multi-site longitudinal study collected data before the departure from Indonesia, and immediately upon arrival | Nasopharyngeal samples were collected pre- and post-Hajj and tested by culturing onto blood agar | 813 | 53.1 | 1:1 | Lung disease (2) Cardiovascular disease (0.8) Liver disease (0.2) Diabetes (5.8) | Pneumococcal vaccine (2) | Pneumococcal infection | S. pneumoniae (8.2) |

| Kandeel et al., 2011 [43] | 2009 | Egyptian | Random selection of pilgrims who returned by ship to Port Tawfiq. Non-random selection of returning pilgrims at Cairo International airport | Throat swabs analysed by RT-PCR | 551 | (12–65) | 1.3:1 | NR | Influenza vaccination (98) | Viral respiratory infections | Influenza A/H3N2 6 (1) |

| Karima et al., 2003 [23] | 2000 | Majority Pakistani (18) Indian (15) Indonesian (12) | All suspected and microbiologically confirmed cases of meningococcal disease referred to public and private hospitals and health centres in Makkah | CSF examination: Gram stain smears, latex agglutination and culture | 105 | 23% (61–70) 22% (41–50) | 1.9:1 | fourteen diabetes one ischemic heart disease one renal failure three hypertension | NR | Meningococcal | Meningitis A, B, W 67 (64) |

| Koul et al., 2018 [44] | 2014–2015 | Indian | Pilgrims were interviewed for respiratory symptoms and tested for respiratory viruses in Srinagar International Airport, Jammu and Kashmir, India | Nasopharyngeal and throat swabs tested by RT-PCR | 300 | 60 (26–60) | 1:1.1 | NR | Influenza vaccine (72) | Viral respiratory infections | Influenza 33 (11) Coronaviruses 52 (17.3) Rhinovirus 20 (6) Other viruses 20 (6) MERS-CoV 0 (0) |

| Lingappa et al., 2003 [24] | 2000 | African (35) Asian (42) Southwest Asian (26) European (4) Middle Eastern (19) | Case data from Ministry of Health surveillance records, regional health directories, clinical laboratory records and inpatient charts from all hospitals in Makkah, Al Madinah and Jeddah | Blood and CSF culture, latex agglutination of CSF | 253 | 40 (0.2–80) | 1.1:1 | NR | NR | Meningococcal | 253 confirmed cases among approx. 1.7 million pilgrims (0.015). Serogroups W 93 (37), A 60 (24), B 4 (2), C 4 (2) |

| Mandourah et al., 2012 [25] | 2009–2010 | Over 40 nationalities | All patients admitted to 15 hospitals in Makkah and Al Madinah | Sputum culture and blood culture | 452 | 64 | 1.8:1 | Diabetes (32.5) Lung diseases (17.1) | NR | Pneumonia | S. pneumoniae 3 (0.7) K. pneumoniae 5 (1.1) S. aureus 3 (0.7) Other bacteria 21 (4.6) |

| Mandourah et al., 2012 [26] | 2009 | East Asian (29.1) South Asian (24.6) Arab (30.9) Black (12.7) White (2.7) | All pilgrims admitted to ICUs of four key hospitals in Makkah | Nasal-swab specimens were tested by RT-PCR | 110 | 60.5 | 1.7:1 | Cardiovascular disease (28.2) Lung disease (20.9) Liver disease (6.4) Diabetes (28.2) Hypertension (31.8) | NR | Viral and bacterial respiratory infections | Influenza A/H1N1 * 24 (21.8) Community- acquired pneumonia 21 (19.3) Tuberculosis 1 (0.9) |

| Memish et al., 2012 [37] | 2009 | Middle Eastern (63) Asian or African (37) | On arrival of pilgrims just before Hajj, and before departure after Hajj at King Abdulaziz International Airport, Jeddah | Nasopharyngeal and throat swabs tested by xTAG Respiratory Viral Panel FAST assay. Specimens positive for influenza A but negative for seasonal H1 and H3 were subjected to additional PCR amplification to detect pandemic H1 and avian H5 | 3550 | 49.4 | 1.4:1 | NR | Influenza vaccine (53.3) | Viral respiratory infections | Influenza 11 (0.5) RSV 8 (0.3) Coronaviruses 10 (0.4) Entero-rhinovirus 351 (13) Other viruses 14 (0.7) |

| Memish et al., 2014 [38] | 2013 | Majority from Indonesia (32.4) Pakistan (18.9) India (10.8) | All pilgrims admitted to 15 healthcare facilities in Makkah and Al Madinah, who were diagnosed with pneumonia | Sputum samples screened for MERS-CoV by RT-PCR and respiratory multiplex array was used to detect up to 22 other viral and bacterial respiratory pathogens | 38 | 58.6 (25–83) | 2.2:1 | NR | NR | Viral and Bacterial respiratory infections | Viruses: Influenza 6 (15.8) Rhinoviruses 15 (39.5) Coronaviruses 5 (13.3) Others 2 (5.2) MERS-CoV 0 (0) Bacteria: S. pneumoniae 13 (34.2) H. influenzae 5 (13.2) Others 10 (26.3) |

| Memish et al., 2014 [39] | 2013 | Majority Indian (17.1) Indonesian (12.9) Pakistani (11.9) Turkish (10.7) | A random selection at the Hajj terminal of King Abdulaziz International Airport, Jeddah, of arriving and departing pilgrims | Nasal swabs analysed by RT-PCR | 5235 | 51.8 (18–93) | 1.2:1 | Diabetes (6.8), Hypertension (13.1) | Influenza vaccine (22), pneumococcal vaccine (4.4) | MERS-CoV | MERS-CoV 0 (0) |

| Memish et al., 2015 [66] | 2013 | African (44.2) Asian (40.2) American (8.4) European (7.2) | Pilgrims recruited upon entering Saudi Arabia at Jeddah International Airport and at Mina camps before leaving Saudi Arabia | Nasal swabs analysed by RT-PCR | 1206 | 50 (18–88) | 1.9:1 | NR | Influenza vaccine (21.9) Pneumococcal vaccine (1.2) | Viral and Bacterial respiratory infections | Viruses: Influenza (3.6) Rhinovirus (34.4) Coronaviruses (19.5) Others (2.4) Bacteria: Meningococcal (0.3) S. pneumoniae (12.7) K. pneumoniae (3.9) S. aureus (7.9) H. influenzae (11.7) |

| Moattari et al., 2012 [46] | 2009 | Iranian | Symptomatic Iranian pilgrims who arrived at Shiraz Airport Iran from Hajj | Throat swabs were collected and tested by virus culture and RT-PCR | 275 | 46 (20–70) | 1:1 | NR | Influenza vaccine (100) | Influenza viruses | Influenza A/H3N2 8 (2.9) Influenza A/H1N1 5 (1.8) Influenza B 20 (7.3) |

| Muraduzzaman et al., 2018 [47] | 2013–2016 | Bangladeshi | Pilgrims and other people returning from the Middle East presented with respiratory symptoms were recruited via active screening at the point of entry | Nasal and throat swabs and sputum tested by RT-PCR | 81 | 49 (14 m–81 y) | 1.2:1 | NR | NR | Viral respiratory infections | Influenza viruses 18 (22.2) Other viruses 6 (7.4) MERS-CoV 0 (0) |

| Refaey et al., 2017 [51] | 2012–2015 | Egyptian | A convenience sample of about 10% of pilgrims from each flight who returned at Cairo International Airport from Hajj | Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected from all participants while sputum specimens collected only from those with respiratory symptoms. Specimens were tested by RT-PCR | 3364 | 56 (0–105) | (1:1.1) | NR | Influenza vaccine (19.7) | Viral respiratory infections | All influenza viruses 484 (14.4) Influenza A/H1N1 117 (3.5) Influenza A/H3N2 187 (5.6) Influenza B 180 (5.4) MERS-CoV 0 (0) |

| Shirah et al., 2017 [30] | 2004–2013 | African (43.9) Asian (51.2) European (3.3) North African (0.7) South American (0.47) Oceanian (0.47) | Clinical data of pilgrims with confirmed pneumonia who attended emergency department of a general hospital in Al Madinah during Hajj | Chest X-ray, throat and nose swabs, sputum and blood culture | 1059 | 56.8 (48–64) | 2.9:1 | Lung disease (15) Diabetes (34.8) Cardiovascular disease (23.3) | NR | Pneumonia | K. pneumoniae 307 (29) S. pneumoniae 1 (1) S. aureus 382 (36) H. influenzae 257 (24) Other bacteria 102 (10) |

| Yavarian et al., 2018 [52] | 2013–2016 | Iranian | Specimens were taken from arriving pilgrims at Emam Khomeini Airport in Tehran | Throat swabs were collected and tested by using one-step RT-PCR | 3840 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Influenza viruses | All influenza viruses 499 (13) Influenza A/H1N1 258 (51.7) Influenza A/H3N2 100 (20) Influenza B 135 (27) MERS-CoV 0 (0) |

| Yezli et al., 2017 [35] | 2015 | Afghan (27.1) Pakistani (25.9) Bangladeshi (19.1) Nigerian (15.1) South African (12.7) | Non-hospitalised adult pilgrims were enrolled during Hajj who had coughs and could voluntarily produce sputum samples | Sputum samples were processed using the Xpert MTB-RIF assay | 1164 | 54.5 (18–94) | 2.6:1 | Hypertension (58.8) Diabetes (42.2) Kidney disease (2) Lung disease (4.4) Liver disease (2.4) Cardiovascular disease (15.9) | NR | Tuberculosis | M. tuberculosis 15 (1.4) |

| Yousuf et al., 2000 [40] | 1992–1993 | Pakistani (53.3) Algerian (13.3) Indonesian, Thai, Syrian, American, and Congolese (6.7) | All patients admitted to King Abdulaziz Hospital, Al Madinah with a diagnosis of meningococcal disease | CSF culture and smear | 15 | NR | 2.7:1 | NR | NR | Meningococcal | Meningococcal infection A and C 8 (53.3) |

| Ziyaeyan et al., 2012 [53] | 2009 | Iranian | One in ten individuals passing through the passport checkout at Shiraz International Airport was selected | Pharyngeal swabs were collected and tested by using RT-PCR | 305 | 49.2 (24–65) | 1:1.3 | NR | Influenza vaccine (97.7) | Influenza viruses | Influenza A/H1N1 4 (1.6) Other influenza A viruses 8 (2.6) |

| Author, Publication Year | Study Year | Participants’ Nationalities (%) | Selection Method/Case Ascertainment | Testing Method | Sample Size | Mean/Median Age (Range) | Male: Female | Risk Factors (%) | Vaccine Uptake (%) | Detected Diseases Name | Disease Burden n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aberle et al., 2015 [55] | 2014 | Austrian | Returning Hajj pilgrims who had sought medical care in different Austrian hospitals/medical centres | Sera, sputa, throat swabs, or bronchoalveolar lavage samples were collected and tested by RT-PCR | 7 | 54 (47–66) | (2.5:1) | Diabetes (43) Hypertension (43) Cardiovascular diseases (12.5) Lung disease (12.5) | NR | Viral respiratory infections | Influenza B 3 (43) Influenza A 2 (29) Rhinovirus 2 (29) MERS-CoV 0 (0) |

| Aguilera et al., 2002 [56] | 2000 | French and British | Hospitalised cases identified by National Surveillance Centres in Europe: only cases in France and UK were used for analysis | Cases were diagnosed by soluble antigen detection or PCR | 90 | 51 | (1:1.1) | NR | NR | Meningococcal | 90 cases of meningococcal W135 disease: pilgrims 12 (13) |

| Al-Abdallat et al., 2017 [57] | 2014 | Jordanian | Returning Hajj pilgrims with symptoms of RTIs were instructed to present to sentinel health facilities in the south, north, and central regions of Jordan | Nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs were collected and tested by RT-PCR | 125 | 51.5 (25–86) | (1.6:1) | Hypertension (22) Diabetes (14) Cardiovascular disease (8) Kidney disease (1) Lung disease (2) | NR | Viral respiratory infections | Rhino/enterovirus 59 (47) Coronavirus 16 (13) Influenza 6 (5) Other viruses 5 (4) MERS-CoV 0 (0) |

| Alahmari et al., 2022 [67] | 2021 | 100 different nationalities | Records of pilgrims who did the PCR test were collected from the official database of the Saudi Ministry of Health | PCR-based surveillance with paired-swab samples (pre-Hajj and post-Hajj) | 58428 | NR | (1:1) | NR | NR | COVID-19 infection | SARS-CoV-2 41 (0.1) |

| Alfelali et al., 2020 [31] | 2013–2015 | Saudi and Qatari (91) Australian (9) | Pilgrims were randomised to ‘facemask’ or ‘no facemask’ by tents in Mina, Makkah | Nasal swabs were collected and tested using a multiplex RT-PCR | 7687 | 34 (18–95) | (1:1.1) | NR | Influenza vaccine: intervention group (49.9) vs. control group (49.4) | Viral respiratory infections | Rhinovirus (35.1) Influenza A/H1N1 and H3N2 (4.5) Parainfluenza (1.7) |

| Alzeer et al., 2023 [70] | 2018 | NR | Samples were collected voluntarily from pilgrims who resided in the study tents | Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected and tested by multiplex RT-PCR | 32 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Viral and bacterial respiratory infections | Viruses: Rhinovirus 5 (15.62) Coronavirus 3 (9.4) Influenza 3 (9.4) Other viruses 7 (21.9) Bacteria: K. pneumoniae 20 (62.5) S. aureus 10 (31.3) S. pneumoniae 5 (15.6) H. influenzae 1 (3.1) Other bacteria 3 (9.4) |

| Atabani et al., 2016 [58] | 2013–2015 | British | UK travellers/pilgrims who returned from the Middle East and presented to hospitals in the Midlands, the Southwest, and North of England with RTI symptoms were actively investigated | Nose and throat swabs, nasopharyngeal aspirates, sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage samples were collected and tested by RT-PCR | 202 | 54 (4 m–85 y) | (1.4:1) | NR | NR | Viral respiratory infections | Influenza 41 (20.3) Rhinovirus 29 (14.4) Other viruses 20 (9.9) MERS-CoV 0 (0) |

| Balkhy et al., 2004 [18] | 2003 | Saudi (46.8) | Patients presented to the National Guard Mina hospital outpatient clinic, on days 10 and 11 of Hajj | Throat swabs were inoculated onto MDCK, A549 and LL19Ks cell lines using conventional methodology, and screened by immunofluorescence for viruses | 500 | Majority (20–40) | (1.1:1) | NR | Influenza vaccine (4.4) | Viral respiratory infections | Influenza 30 (7) Other viruses 24 (4.8) |

| Barasheed et al., 2014 [33] | 2013 | Australian, Saudi, and Qatari | Pilgrims were recruited during the first day of Hajj and followed closely for four days | Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected and tested by multiplex RT-PCR | 112 | 35 (18–75) | (1:1.3) | Lung disease (68) Diabetes (41) Cardiovascular disease (4) Kidney disease (4) | Influenza vaccine (68.8) | Viral respiratory infections | Rhinovirus 28 (25) Influenza 5 (4) Coronavirus 2 (2) Other viruses 5 (4) |

| Barasheed et al., 2014 [34] | 2011 | Australian | Tents were randomised to ‘supervised mask use’ versus ‘no supervised mask use’. Pilgrims with ILI symptoms for ≤3 days were recruited as ‘cases’ and those who slept within 2 m of them as ‘contacts’ | Nasal swabs were taken and tested using Quick-Vue A+B point-of-care test and NAT for influenza viruses | 164 | 44.1 (17–80) | (1:1.3) | NR | NR | Viral respiratory infections | Rhinovirus 39 (23.8) Influenza 7 (4.3) Other viruses 2 (1.2) |

| Benkouiten et al., 2013 [60] | 2012 | French | A prospective survey among a cohort of pilgrims departing from Marseille, France, to Makkah for Hajj | Nasal swabs were collected and tested by RT-PCR | 154 | 59.3 (21–83) | (1:1.6) | Diabetes (27.5) Hypertension (26.3) Lung disease (7.8) Cardiovascular disease (7.2) | Influenza vaccine (45.6) Pneumococcal vaccine (35.9) | Viral respiratory infections | Rhinovirus 13 (8.4) Influenza 2 (1.3) Other viruses 4 (2.6) |

| Benkouiten et al., 2014 [61] | 2013 | French | Pilgrims were recruited at a private specialised travel agency in Marseille, France. participants were sampled and followed up before departing from France and before leaving Saudi Arabia | Paired nasal and throat swab specimens were collected and tested by RT-PCR | 129 | 61.7 (34–85) | (1:1.5) | NR | Influenza vaccine (0) Pneumococcal vaccine (51.2) | Viral and bacterial respiratory infections | Viruses: Influenza 10 (7.8) Coronavirus 27 (20.9) Rhinovirus 19 (14.7) MERS-CoV 0(0) Bacteria: S. pneumoniae 80 (62) |

| El Bashir et al., 2004 [65] | 2003 | British | A cohort of pilgrims from the East End of London who participated in Hajj | Blood samples were collected pre-and post-Hajj, and tested by haemagglutination inhibition | 115 | NR | NR | NR | Influenza vaccine (26) | Influenza viruses | All influenza viruses 44 (38) Influenza A/H3N2 42 (37) Influenza A/H1N1 1 (0.9) Influenza B 1 (0.9) |

| Erdem et al., 2016 [59] | 201–2015 | Turkish | In patients with a diagnosis of a travel-associated infection needing hospitalisation after returning from the Arabian Peninsula. Data were collected retrospectively from infectious diseases departments of 15 Turkish referral centres | Microbiological cultures were used for bacteria and Multiplex/RT-PCR was used for viruses | 185 | 60.3 | (1:1.1) | Diabetes (24.3) Hypertension (8.6) Cardiovascular disease (10.8) Liver disease (1.1) Kidney disease (0.54) Lung disease (14.1) | NR | Viral and bacterial respiratory infections | Viruses: Influenza 15 (8.1) Coronavirus 1 (0.5) Rhinovirus 1 (0.5) Other viruses 3 (1.6) Bacteria: S. pneumoniae 1 (0.5) H. influenzae 1 (0.5) Other bacteria 1 (0.5) |

| Hoang et al., 2022 [62] | 2014–2018 | French | Hajj pilgrims from Marseille, France, were recruited through a private specialised travel agency and were systematically sampled before departing and upon their return from Hajj | Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected and tested by RT-PCR | 207 | NR | NR | Diabetes (32.4) Hypertension (28) Lung disease (15) Cardiovascular disease (9.7) Kidney disease (1.9) | Influenza vaccine (29.5) Pneumococcal vaccine (30.9) | Viral and bacterial respiratory infections | Viruses: Rhinovirus (40.6) Coronavirus (15.5) Influenza (2.9) Bacteria: S. aureus (35.8) H. influenzae (30.4) K. pneumoniae (17.4) S. pneumoniae (3.9) |

| Jones et al., 1990 [68] | 1987–1988 | British | Meningococcal Reference Laboratory | Nasal swabs were cultured | 39 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Meningococcal | Meningococcal A (0.18) |

| Ma et al., 2017 [45] | 2013–2015 | Chinese | Randomly selected returning pilgrims arriving at Xinjiang and Gansu airports | Viral infection samples collected and tested by RT-PCR | 847 | 2.24 | (1.4:1) | NR | Influenza vaccine (100) | Viral respiratory infections | Influenza 48 (5.7) Coronavirus 3 (0.3) MERS-CoV 0 (0) |

| Marglani et al., 2016 [27] | 2014 | Gulf (58) Asian (12.4) South Asian (11.9) North African (11.5) African (3.5) European (2.2) American (0.5) | Patients presented to the emergency or outpatient departments of Alnoor Specialised Hospital in Makkah | Bacteriological culture and isolation, and antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) were performed using MicroScan Walk Away System ID/AST | 226 | 34.6 (9–77) | (3.5:1) | NR | NR | Bacterial acute rhinosinusitis | S. aureus 46 (20.3) |

| Matsika-Claquin et al., 2001 [69] | 2000 | French | Standardised questionnaire used to interrogate study subjects | A case was considered to be confirmed when the strain isolated from usually sterile media was found to be identical to the epidemic strain (W135, 2a: P1-2.5--clonal complex ET37) | 27 | (2 m–87 y) | (1:1.2) | NR | NR | Meningococcal | Meningococcal W (0.002) |

| Nik Zuraina et al., 2018 [48] | 2016 | Malaysian | Hajj pilgrims who returned to the arrival hall of Sultan Ismail Airport, Kota Bharu, Kelantan, Malaysia with RTI symptoms, including productive cough | Bacteriological culture method and Vitek II system | 297 | 57.4 (27–82) | (1:1) | NR | NR | Bacterial respiratory infections | H. influenzae 123 (44.4) K. pneumoniae 11 (3.7) S. pneumoniae 2 (0.7) Other bacteria 28 (9.4) |

| Nik Zuraina et al., 2022 [49] | 2016 | Malaysian | Hajj pilgrims who returned to Sultan Ismail Petra Airport, Kelantan, Malaysia with RTI symptoms during Hajj | Sputum specimens were collected and tested by culture and thermostabilized, multiplex PCR | 202 | 56.7 (26–80) | (1:1.1) | NR | NR | Bacterial respiratory infections | H. influenzae 88 (43.5) K. pneumoniae 1 (0.5) S. pneumoniae 2 (1) Other bacteria 20 (9.9) |

| Novelli et al., 1987 [50] | 1987 | Qatari | Returning pilgrims or their contacts admitted to Hamad General Hospital, Doha, Qatar | Blood and/or CSF culture and/or latex test for meningococcal antigen in CSF | 15 | 40 | NR | NR | NR | Meningococcal | Meningococcal A 6 (40) |

| Rashid et al., 2008 [28] | 2005 | British | Pilgrims attending the British Hajj Delegation Medical Clinic in Makkah and in tents in Mina with symptoms of upper RTI | Two nasal swabs taken and tested by testing using PoCT and RT-PCR | 202 | 44 (1.5–83) | (9.1:1) | Diabetes, chronic heart, lung or kidney disease, all high-risk conditions together (26) | Influenza vaccine (28) | Viral respiratory infections | Influenza 28 (13.9) RSV 9 (4) |

| Rashid et al., 2008 [29] | 2006 | British | Hajj pilgrims with upper RTI who attended British Hajj Delegation Clinic in Makkah and Mina | Two nasal swabs taken and tested by testing using PoCT and RT-PCR | 150 | 41 (14–81) | (11.5:1) | Diabetes (62) Lung disease (23) Cardiovascular disease (12) | Influenza vaccine (37.3) | Viral respiratory infections | Influenza 17 (11) Rhinovirus 19 (12.7) Other viruses 2 (1.3) |

| Wilder-Smith et al., 2003 [63] | 2002 | Singaporean | Referred by travel agencies, pilgrims were recruited at a Muslim centre in Singapore that performs mass vaccinations and following a few months after Hajj | Paired blood samples were collected pre- and post-Hajj, and IgG antibodies for pertussis whole-cell antigen were measured | 358 | 48 (16–75) | (1:1.7) | NR | NR | Pertussis | Bordetella pertussis 5 (1.4) |

| Wilder-Smith et al., 2005 [64] | 2002 | Singaporean | Pilgrims were consecutively recruited at mass pre-travel vaccination sites before Hajj and following a few months after Hajj | A whole-blood assay (Quanti- FERON TB assay) prior to departure and 3 months after return from Hajj | 365 | 49.2 (18–75) | (1:1.6) | Diabetes (8.8) | NR | Tuberculosis | M. tuberculosis 139 (38) |

3.2. Comparative Variables and Attack Rates of Hajj-Acquired Airborne Infections

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gatrad, A.R.; Sheikh, A. Hajj: Journey of a lifetime. BMJ 2005, 330, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, A.S.; Alshahrani, A.M.; Rashid, H. Health Issues of Mass Gatherings in the Middle East. In Handbook of Healthcare in the Arab World; Laher, I., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1183–1198. [Google Scholar]

- Cobbin, J.C.A.; Alfelali, M.; Barasheed, O.; Taylor, J.; Dwyer, D.E.; Kok, J.; Booy, R.; Holmes, E.C.; Rashid, H. Multiple Sources of Genetic Diversity of Influenza A Viruses during the Hajj. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e00096-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almehmadi, M.; Alqahtani, J.S. Healthcare Research in Mass Religious Gatherings and Emergency Management: A Comprehensive Narrative Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, A.S.; Tashani, M.; Ridda, I.; Gamil, A.; Booy, R.; Rashid, H. Burden of clinical infections due to S. pneumoniae during Hajj: A systematic review. Vaccine 2018, 36, 4440–4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautret, P.; Benkouiten, S. Circulation of respiratory pathogens at mass gatherings, with special focus on the Hajj pilgrimage. In The Microbiology of Respiratory System Infections; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Basahel, S.; Alsabban, A.; Yamin, M. Hajj and Umrah management during COVID-19. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 2021, 13, 2491–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Benkouiten, S.; Memish, Z.A. A systematic review of emerging respiratory viruses at the Hajj and possible coinfection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. Travel. Med. Infect. Dis. 2018, 23, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkouiten, S.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Memish, Z.A.; Albarrak, A.; Gautret, P. Clinical respiratory infections and pneumonia during the Hajj pilgrimage: A systematic review. Travel. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 28, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarpour, H.; Safi-Keykaleh, M.; Farahi-Ashtiani, I.; Bazyar, J.; Daliri, S.; Sahebi, A. Prevalence of Influenza Among Hajj Pilgrims: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 16, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautret, P.; Benkouiten, S.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Memish, Z.A. Hajj-associated viral respiratory infections: A systematic review. Travel. Med. Infect. Dis. 2016, 14, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlBarrak, A.; Alotaibi, B.; Yassin, Y.; Mushi, A.; Maashi, F.; Seedahmed, Y.; Alshaer, M.; Altaweel, A.; Elshiekh, H.; Turkistani, A.; et al. Proportion of adult community-acquired pneumonia cases attributable to Streptococcus pneumoniae among Hajj pilgrims in 2016. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 69, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsayed, S.M.; Alandijany, T.A.; El-Kafrawy, S.A.; Hassan, A.M.; Bajrai, L.H.; Faizo, A.A.; Mulla, E.A.; Aljahdali, L.S.; Alquthami, K.M.; Zumla, A.; et al. Pattern of Respiratory Viruses among Pilgrims during 2019 Hajj Season Who Sought Healthcare Due to Severe Respiratory Symptoms. Pathogens 2021, 10, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asghar, A.H.; Ashshi, A.M.; Azhar, E.I.; Bukhari, S.Z.; Zafar, T.A.; Momenah, A.M. Profile of bacterial pneumonia during Hajj. Indian. J. Med. Res. 2011, 133, 510–513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baharoon, S.; Al-Jahdali, H.; Al Hashmi, J.; Memish, Z.A.; Ahmed, Q.A. Severe sepsis and septic shock at the Hajj: Etiologies and outcomes. Travel. Med. Infect. Dis. 2009, 7, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokhary, H.; Research Team, H.; Barasheed, O.; Othman, H.B.; Saha, B.; Rashid, H.; Hill-Cawthorne, G.A.; Abd El Ghany, M. Evaluation of the rate, pattern and appropriateness of antibiotic prescription in a cohort of pilgrims suffering from upper respiratory tract infection during the 2018 Hajj season. Access Microbiol. 2022, 4, 000338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balkhy, H.H.; Memish, Z.A.; Bafaqeer, S.; Almuneef, M.A. Influenza a common viral infection among Hajj pilgrims: Time for routine surveillance and vaccination. J. Travel. Med. 2004, 11, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- El-Gamal, S.A.; Saleh, L.H. An outbreak of meningococcal infection at the time of pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia. J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc. 1988, 63, 263–274. [Google Scholar]

- El-Kafrawy, S.A.; Alsayed, S.M.; Alandijany, T.A.; Bajrai, L.H.; Faizo, A.A.; Al-Sharif, H.A.; Hassan, A.M.; Alquthami, K.M.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Zumla, A.; et al. High genetic diversity of human rhinovirus among pilgrims with acute respiratory tract infections during the 2019 Hajj pilgrimage season. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 121, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheikh, S.M.; El-Assouli, S.M.; Mohammed, K.A.; Albar, M. Bacteria and viruses that cause respiratory tract infections during the pilgrimage (Haj) season in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Trop. Med. Int. Health 1998, 3, 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Hashem, A.M.; Al-Subhi, T.L.; Badroon, N.A.; Hassan, A.M.; Bajrai, L.H.M.; Banassir, T.M.; Alquthami, K.M.; Azhar, E.I. MERS-CoV, influenza and other respiratory viruses among symptomatic pilgrims during 2014 Hajj season. J. Med. Virol. 2019, 91, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karima, T.M.; Bukhari, S.Z.; Fatani, M.I.; Yasin, K.A.; Al-Afif, K.A.; Hafiz, F.H. Clinical and microbiological spectrum of meningococcal disease in adults during Hajj 2000: An implication of quadrivalent vaccination policy. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2003, 53, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lingappa, J.R.; Al-Rabeah, A.M.; Hajjeh, R.; Mustafa, T.; Fatani, A.; Al-Bassam, T.; Badukhan, A.; Turkistani, A.; Makki, S.; Al-Hamdan, N.; et al. Serogroup W-135 meningococcal disease during the Hajj, 2000. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2003, 9, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandourah, Y.; Al-Radi, A.; Ocheltree, A.H.; Ocheltree, S.R.; Fowler, R.A. Clinical and temporal patterns of severe pneumonia causing critical illness during Hajj. BMC Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandourah, Y.; Ocheltree, A.; Al Radi, A.; Fowler, R. The epidemiology of Hajj-related critical illness: Lessons for deployment of temporary critical care services. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marglani, O.A.; Alherabi, A.Z.; Herzallah, I.R.; Saati, F.A.; Tantawy, E.A.; Alandejani, T.A.; Faidah, H.S.; Bawazeer, N.A.; Marghalani, A.A.; Madani, T.A. Acute rhinosinusitis during Hajj season 2014: Prevalence of bacterial infection and patterns of antimicrobial susceptibility. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2016, 14, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, H.; Shafi, S.; Booy, R.; El Bashir, H.; Ali, K.; Zambon, M.; Memish, Z.; Ellis, J.; Coen, P.; Haworth, E. Influenza and respiratory syncytial virus infections in British Hajj pilgrims. Emerg. Health Threats J. 2008, 1, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, H.; Shafi, S.; Haworth, E.; El Bashir, H.; Memish, Z.A.; Sudhanva, M.; Smith, M.; Auburn, H.; Booy, R. Viral respiratory infections at the Hajj: Comparison between UK and Saudi pilgrims. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008, 14, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirah, B.H.; Zafar, S.H.; Alferaidi, O.A.; Sabir, A.M.M. Mass gathering medicine (Hajj Pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia): The clinical pattern of pneumonia among pilgrims during Hajj. J. Infect. Public Health 2017, 10, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfelali, M.; Haworth, E.A.; Barasheed, O.; Badahdah, A.M.; Bokhary, H.; Tashani, M.; Azeem, M.I.; Kok, J.; Taylor, J.; Barnes, E.H.; et al. Facemask against viral respiratory infections among Hajj pilgrims: A challenging cluster-randomized trial. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzeer, A.; Mashlah, A.; Fakim, N.; Al-Sugair, N.; Al-Hedaithy, M.; Al-Majed, S.; Jamjoom, G. Tuberculosis is the commonest cause of pneumonia requiring hospitalization during Hajj (pilgrimage to Makkah). J. Infect. 1998, 36, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barasheed, O.; Almasri, N.; Badahdah, A.M.; Heron, L.; Taylor, J.; McPhee, K.; Ridda, I.; Haworth, E.; Dwyer, D.E.; Rashid, H.; et al. Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial to Test Effectiveness of Facemasks in Preventing Influenza-like Illness Transmission among Australian Hajj Pilgrims in 2011. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 2014, 14, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barasheed, O.; Rashid, H.; Alfelali, M.; Tashani, M.; Azeem, M.; Bokhary, H.; Kalantan, N.; Samkari, J.; Heron, L.; Kok, J.; et al. Viral respiratory infections among Hajj pilgrims in 2013. Virol. Sin. 2014, 29, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yezli, S.; Zumla, A.; Yassin, Y.; Al-Shangiti, A.M.; Mohamed, G.; Turkistani, A.M.; Alotaibi, B. Undiagnosed Active Pulmonary Tuberculosis among Pilgrims during the 2015 Hajj Mass Gathering: A Prospective Cross-sectional Study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 97, 1304–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ashshi, A.; Azhar, E.; Johargy, A.; Asghar, A.; Momenah, A.; Turkestani, A.; Alghamdi, S.; Memish, Z.; Al-Ghamdi, A.; Alawi, M.; et al. Demographic distribution and transmission potential of influenza A and 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 in pilgrims. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2014, 8, 1169–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memish, Z.A.; Assiri, A.M.; Hussain, R.; Alomar, I.; Stephens, G. Detection of respiratory viruses among pilgrims in Saudi Arabia during the time of a declared influenza A(H1N1) pandemic. J. Travel. Med. 2012, 19, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memish, Z.A.; Assiri, A.; Almasri, M.; Alhakeem, R.F.; Turkestani, A.; Al Rabeeah, A.A.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Alzahrani, A.; Azhar, E.; Makhdoom, H.Q.; et al. Prevalence of MERS-CoV nasal carriage and compliance with the Saudi health recommendations among pilgrims attending the 2013 Hajj. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 210, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memish, Z.A.; Assiri, A.; Turkestani, A.; Yezli, S.; Al Masri, M.; Charrel, R.; Drali, T.; Gaudart, J.; Edouard, S.; Parola, P.; et al. Mass gathering and globalization of respiratory pathogens during the 2013 Hajj. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 571.e1–571.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousuf, M.; Nadeem, A. Meningococcal infection among pilgrims visiting Madinah Al-Munawarah despite prior A-C vaccination. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2000, 50, 184–186. [Google Scholar]

- Alborzi, A.; Aelami, M.H.; Ziyaeyan, M.; Jamalidoust, M.; Moeini, M.; Pourabbas, B.; Abbasian, A. Viral etiology of acute respiratory infections among Iranian Hajj pilgrims, 2006. J. Travel Med. 2009, 16, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annan, A.; Owusu, M.; Marfo, K.S.; Larbi, R.; Sarpong, F.N.; Adu-Sarkodie, Y.; Amankwa, J.; Fiafemetsi, S.; Drosten, C.; Owusu-Dabo, E.; et al. High prevalence of common respiratory viruses and no evidence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Hajj pilgrims returning to Ghana, 2013. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2015, 20, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandeel, A.; Deming, M.; Elkreem, E.A.; El-Refay, S.; Afifi, S.; Abukela, M.; Earhart, K.; El-Sayed, N.; El-Gabay, H. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 and Hajj Pilgrims who received Predeparture Vaccination, Egypt. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 1266–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koul, P.A.; Mir, H.; Saha, S.; Chadha, M.S.; Potdar, V.; Widdowson, M.A.; Lal, R.B.; Krishnan, A. Respiratory viruses in returning Hajj & Umrah pilgrims with acute respiratory illness in 2014–2015. Indian J. Med. Res. 2018, 148, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Liu, F.; Liu, L.; Zhang, L.; Lu, M.; Abudukadeer, A.; Wang, L.; Tian, F.; Zhen, W.; Yang, P.; et al. No MERS-CoV but positive influenza viruses in returning Hajj pilgrims, China, 2013–2015. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moattari, A.; Emami, A.; Moghadami, M.; Honarvar, B. Influenza viral infections among the Iranian Hajj pilgrims returning to Shiraz, Fars province, Iran. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2012, 6, e77–e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraduzzaman, A.K.M.; Khan, M.H.; Parveen, R.; Sultana, S.; Alam, A.N.; Akram, A.; Rahman, M.; Shirin, T. Event based surveillance of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS- CoV) in Bangladesh among pilgrims and travelers from the Middle East: An update for the period 2013–2016. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0189914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nik Zuraina, N.M.N.; Sarimah, A.; Suharni, M.; Hasan, H.; Suraiya, S. High frequency of Haemophilus influenzae associated with respiratory tract infections among Malaysian Hajj pilgrims. J. Infect. Public Health 2018, 11, 878–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor Nik Zuraina, N.M.; Hasan, H.; Mohamad, S.; Suraiya, S. Diagnostic detection of intended bacteria associated with respiratory tract infections among Kelantanese Malaysian Hajj pilgrims by a ready-to-use, thermostable multiplex PCR assay. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 103349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, V.M.; Lewis, R.G.; Dawood, S.T. Epidemic group A meningococcal disease in Haj pilgrims. Lancet 1987, 2, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refaey, S.; Amin, M.M.; Roguski, K.; Azziz-Baumgartner, E.; Uyeki, T.M.; Labib, M.; Kandeel, A. Cross-sectional survey and surveillance for influenza viruses and MERS-CoV among Egyptian pilgrims returning from Hajj during 2012–2015. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2017, 11, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavarian, J.; Shafiei Jandaghi, N.Z.; Naseri, M.; Hemmati, P.; Dadras, M.; Gouya, M.M.; Mokhtari Azad, T. Influenza virus but not MERS coronavirus circulation in Iran, 2013–2016: Comparison between pilgrims and general population. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2018, 21, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziyaeyan, M.; Alborzi, A.; Jamalidoust, M.; Moeini, M.; Pouladfar, G.R.; Pourabbas, B.; Namayandeh, M.; Moghadami, M.; Bagheri-Lankarani, K.; Mokhtari-Azad, T. Pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection among 2009 Hajj Pilgrims from Southern Iran: A real-time RT-PCR-based study. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2012, 6, e80–e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harimurti, K.; Saldi, S.R.F.; Dewiasty, E.; Alfarizi, T.; Dharmayuli, M.; Khoeri, M.M.; Paramaiswari, W.T.; Salsabila, K.; Tafroji, W.; Halim, C.; et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage and antibiotic susceptibility among Indonesian pilgrims during the Hajj pilgrimage in 2015. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberle, J.H.; Popow-Kraupp, T.; Kreidl, P.; Laferl, H.; Heinz, F.X.; Aberle, S.W. Influenza A and B Viruses but Not MERS-CoV in Hajj Pilgrims, Austria, 2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 726–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilera, J.F.; Perrocheau, A.; Meffre, C.; Hahne, S.; Group, W.W. Outbreak of serogroup W135 meningococcal disease after the Hajj pilgrimage, Europe, 2000. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002, 8, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Abdallat, M.M.; Rha, B.; Alqasrawi, S.; Payne, D.C.; Iblan, I.; Binder, A.M.; Haddadin, A.; Nsour, M.A.; Alsanouri, T.; Mofleh, J.; et al. Acute respiratory infections among returning Hajj pilgrims-Jordan, 2014. J. Clin. Virol. 2017, 89, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabani, S.F.; Wilson, S.; Overton-Lewis, C.; Workman, J.; Kidd, I.M.; Petersen, E.; Zumla, A.; Smit, E.; Osman, H. Active screening and surveillance in the United Kingdom for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in returning travellers and pilgrims from the Middle East: A prospective descriptive study for the period 2013-2015. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 47, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, H.; Ak, O.; Elaldi, N.; Demirdal, T.; Hargreaves, S.; Nemli, S.A.; Cag, Y.; Ulug, M.; Naz, H.; Gunal, O.; et al. Infections in travellers returning to Turkey from the Arabian peninsula: A retrospective cross-sectional multicenter study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 35, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkouiten, S.; Charrel, R.; Belhouchat, K.; Drali, T.; Nougairede, A.; Salez, N.; Memish, Z.A.; Al Masri, M.; Fournier, P.E.; Raoult, D.; et al. Respiratory viruses and bacteria among pilgrims during the 2013 Hajj. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 1821–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkouiten, S.; Charrel, R.; Belhouchat, K.; Drali, T.; Salez, N.; Nougairede, A.; Zandotti, C.; Memish, Z.A.; Al Masri, M.; Gaillard, C.; et al. Circulation of respiratory viruses among pilgrims during the 2012 Hajj pilgrimage. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, V.T.; Dao, T.L.; Ly, T.D.A.; Drali, T.; Yezli, S.; Parola, P.; Pommier de Santi, V.; Gautret, P. Respiratory pathogens among ill pilgrims and the potential benefit of using point-of-care rapid molecular diagnostic tools during the Hajj. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2022, 69, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder-Smith, A.; Earnest, A.; Ravindran, S.; Paton, N.I. High incidence of pertussis among Hajj pilgrims. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 37, 1270–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder-Smith, A.; Foo, W.; Earnest, A.; Paton, N.I. High risk of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection during the Hajj pilgrimage. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2005, 10, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Bashir, H.; Haworth, E.; Zambon, M.; Shafi, S.; Zuckerman, J.; Booy, R. Influenza among U.K. pilgrims to hajj, 2003. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1882–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memish, Z.A.; Almasri, M.; Turkestani, A.; Al-Shangiti, A.M.; Yezli, S. Etiology of severe community-acquired pneumonia during the 2013 Hajj-part of the MERS-CoV surveillance program. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 25, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alahmari, A.A.; Khan, A.A.; Alamri, F.A.; Almuzaini, Y.S.; Alradini, F.A.; Almohamadi, E.; Alsaeedi, S.; Asiri, S.; Motair, W.; Almadah, A.; et al. Hajj 2021: Role of mitigation measures for health security. J. Infect. Public Health 2022, 15, 1350–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.M.; Sutcliffe, E.M. Group A meningococcal disease in England associated with the Haj. J. Infect. 1990, 21, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsika-Claquin, M.D.; Perrocheau, A.; Taha, M.K.; Levy-Bruhl, D.; Renault, P.; Alonso, J.M.; Desenclos, J.C. Meningococcal W135 infection epidemics associated with pilgrimage to Mecca in 2000. Presse Med. 2001, 30, 1529–1534. [Google Scholar]

- Alzeer, A.H.; Somily, A.; Aldosari, K.M.; Ahamed, S.S.; Saadon, A.H.A.; Mohamed, D.H. Microbial surveillance of Hajj tents: Bioaerosol sampling coupled with real-time multiplex PCR. Am. J. Infect. Control 2023, 51, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, N.S.; Al-Barrak, A.M.; Al-Moamary, M.S.; Zeitouni, M.O.; Idrees, M.M.; Al-Ghobain, M.O.; Al-Shimemeri, A.A.; Al-Hajjaj, M.S. The Saudi Thoracic Society pneumococcal vaccination guidelines-2016. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2016, 11, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsuhebany, N.; Alowais, S.A.; Aldairem, A.; Almohareb, S.N.; Bin Saleh, K.; Kahtani, K.M.; Alnashwan, L.I.; Alay, S.M.; Alamri, M.G.; Alhathlol, G.K.; et al. Identifying gaps in vaccination perception after mandating the COVID-19 vaccine in Saudi Arabia. Vaccine 2023, 41, 3611–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, H.; Abdul Muttalif, A.R.; Mohamed Dahlan, Z.B.; Djauzi, S.; Iqbal, Z.; Karim, H.M.; Naeem, S.M.; Tantawichien, T.; Zotomayor, R.; Patil, S.; et al. The potential for pneumococcal vaccination in Hajj pilgrims: Expert opinion. Travel. Med. Infect. Dis. 2013, 11, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albutti, A.; Mahdi, H.A.; Alwashmi, A.S.; Alfelali, M.; Barasheed, O.; Barnes, E.H.; Shaban, R.Z.; Booy, R.; Rashid, H. The relationship between hand hygiene and rates of acute respiratory infections among Umrah pilgrims: A pilot randomised controlled trial. J. Infect. Public Health, 2023; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, Q.A.; Memish, Z.A. Hajj 2022 and the post pandemic mass gathering: Epidemiological data and decision making. New Microbes New Infect. 2022, 49–50, 101033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Statement on the Fifteenth Meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Alarabiya News. Saudi Arabia to Host Pre-Pandemic Numbers for 2023 Hajj Pilgrimage Season. Available online: https://english.alarabiya.net/News/saudi-arabia/2023/01/09/Saudi-Arabia-to-host-pre-pandemic-numbers-for-2023-Hajj-pilgrimage-season (accessed on 27 May 2023).

| Variables | Low and Middle-Income Countries | High-Income Countries |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Pooled study sample | 27,799 | 70,865 |

| Age (range) | 2 d–105 y | 2 m–95 y |

| Male: Female | 1.3:1 | 1:1 |

| Vaccination uptake (%) | ||

| Influenza vaccination | 19.7–100 | 0–100 |

| Pneumococcal vaccination | 1.2–4.4 | 30.9–51.2 |

| Risk factors (%) | ||

| Diabetes | 5.8–36 | 0.9–32.4 |

| Hypertension | 2.9–43 | 8.6–28 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 0.8–43 | 0.1–10.8 |

| Chronic lung disease | 1.1–71 | 1.4–15 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0.5–2 | 0.1–1.9 |

| Chronic liver disease | 0.2–6.4 | 1.1 |

| Attack rate of viral airborne infections (%) | ||

| Influenza | 0.5–29.5 | 1.3–38 |

| Human rhinovirus | 5.9–39.5 | 0.5–47 |

| Human coronavirus | 0.4–19.5 | 0.1–20.9 |

| Other viruses | 0.7–16.4 | 0.7–21.9 |

| Attack rate of bacterial airborne infections (%) | ||

| Meningococci | 0.015–82 | 0.002–40 |

| M. tuberculosis | 0.7–20.3 | 38 |

| S. pneumoniae | 1–54.8 | 0.5–62 |

| K. pneumoniae | 1.1–29 | 0.5–62.5 |

| H. influenza | 4.7–24 | 0.5–44.4 |

| S. aureus | 0.7–36 | 20.3–35.8 |

| Other bacteria | 0.8–50 | 0.5–9.9 |

| Studies | Selection (Max 4 Stars) | Comparability (Max 2 Stars) | Outcome/Exposure (Max 3 Stars) | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-income countries (HIC) | ||||

| Aberle et al., 2015 [55] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Aguilera et al., 2002 [56] | *** | – | *** | 6 |

| Al-Abdallat et al., 2017 [57] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Alahmari et al., 2022 [67] | *** | – | *** | 6 |

| Alfelali et al., 2020 [31] | *** | * | ** | 6 |

| Alzeer et al., 2023 [70] | *** | – | ** | 5 |

| Atabani et al., 2016 [58] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Balkhy et al., 2004 [18] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Barasheed et al., 2014 [33] | *** | * | ** | 6 |

| Barasheed et al., 2014 [34] | *** | * | ** | 6 |

| Benkouiten et al., 2013 [60] | *** | – | *** | 6 |

| Benkouiten et al., 2014 [61] | *** | – | *** | 6 |

| El Bashir et al., 2004 [65] | *** | – | *** | 6 |

| Erdem et al., 2016 [59] | ** | – | *** | 5 |

| Hoang et al., 2022 [62] | *** | – | *** | 6 |

| Jones et al., 1990 [68] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Ma et al., 2017 [45] | ** | – | *** | 5 |

| Marglani et al., 2016 [27] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Matsika-Claquin et al., 2001 [69] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Nik Zuraina et al., 2018 [48] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Nik Zuraina et al., 2022 [49] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Novelli et al., 1987 [50] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Rashid et al., 2008 [28] | ** | – | *** | 5 |

| Rashid et al., 2008 [29] | ** | – | *** | 5 |

| Wilder-Smith et al., 2003 [63] | *** | – | ** | 5 |

| Wilder-Smith et al., 2005 [64] | *** | – | ** | 5 |

| Low and middle-income countries (LMIC) | ||||

| AlBarrak et al., 2018 [13] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Alborzi et al., 2009 [41] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Alsayed et al., 2021 [14] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Alzeer et al., 1998 [32] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Annan et al., 2015 [42] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Asghar et al., 2011 [15] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Ashshi et al., 2014 [36] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Baharoon et al., 2009 [16] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Bokhary et al., 2022 [17] | ** | – | * | 3 |

| El-Gamal et al., 1988 [19] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| El-Kafrawy et al., 2022 [20] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| El-Sheikh et al., 1998 [21] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Hashem et al., 2019 [22] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Harimurti et al., 2021 [54] | *** | – | *** | 6 |

| Kandeel et al., 2011 [43] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Karima et al., 2003 [23] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Koul et al., 2018 [44] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Lingappa et al., 2003 [24] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Mandourah et al., 2012 [25] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Mandourah et al., 2012 [26] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Memish et al., 2012 [37] | *** | – | *** | 6 |

| Memish et al., 2014 [38] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Memish et al., 2014 [66] | *** | – | *** | 6 |

| Memish et al., 2015 [39] | *** | – | *** | 6 |

| Moattari et al., 2012 [46] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Muraduzzaman et al., 2018 [47] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Refaey et al., 2017 [51] | *** | – | ** | 5 |

| Shirah et al., 2017 [30] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Yavarian et al., 2018 [52] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Yezli et al., 2017 [35] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Yousuf et al., 2000 [40] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

| Ziyaeyan et al., 2012 [53] | ** | – | ** | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mahdi, H.A.; Alluhidan, M.; Almohammed, A.B.; Alfelali, M.; Shaban, R.Z.; Booy, R.; Rashid, H. Epidemiological Differences in Hajj-Acquired Airborne Infections in Pilgrims Arriving from Low and Middle-Income versus High-Income Countries: A Systematised Review. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8080418

Mahdi HA, Alluhidan M, Almohammed AB, Alfelali M, Shaban RZ, Booy R, Rashid H. Epidemiological Differences in Hajj-Acquired Airborne Infections in Pilgrims Arriving from Low and Middle-Income versus High-Income Countries: A Systematised Review. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2023; 8(8):418. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8080418

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahdi, Hashim A., Mohammed Alluhidan, Abdulrahman B. Almohammed, Mohammad Alfelali, Ramon Z. Shaban, Robert Booy, and Harunor Rashid. 2023. "Epidemiological Differences in Hajj-Acquired Airborne Infections in Pilgrims Arriving from Low and Middle-Income versus High-Income Countries: A Systematised Review" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 8, no. 8: 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8080418

APA StyleMahdi, H. A., Alluhidan, M., Almohammed, A. B., Alfelali, M., Shaban, R. Z., Booy, R., & Rashid, H. (2023). Epidemiological Differences in Hajj-Acquired Airborne Infections in Pilgrims Arriving from Low and Middle-Income versus High-Income Countries: A Systematised Review. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 8(8), 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8080418