Feasibility and Acceptability of a Strategy Deploying Multiple First-Line Artemisinin-Based Combination Therapies for Uncomplicated Malaria in the Health District of Kaya, Burkina Faso

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

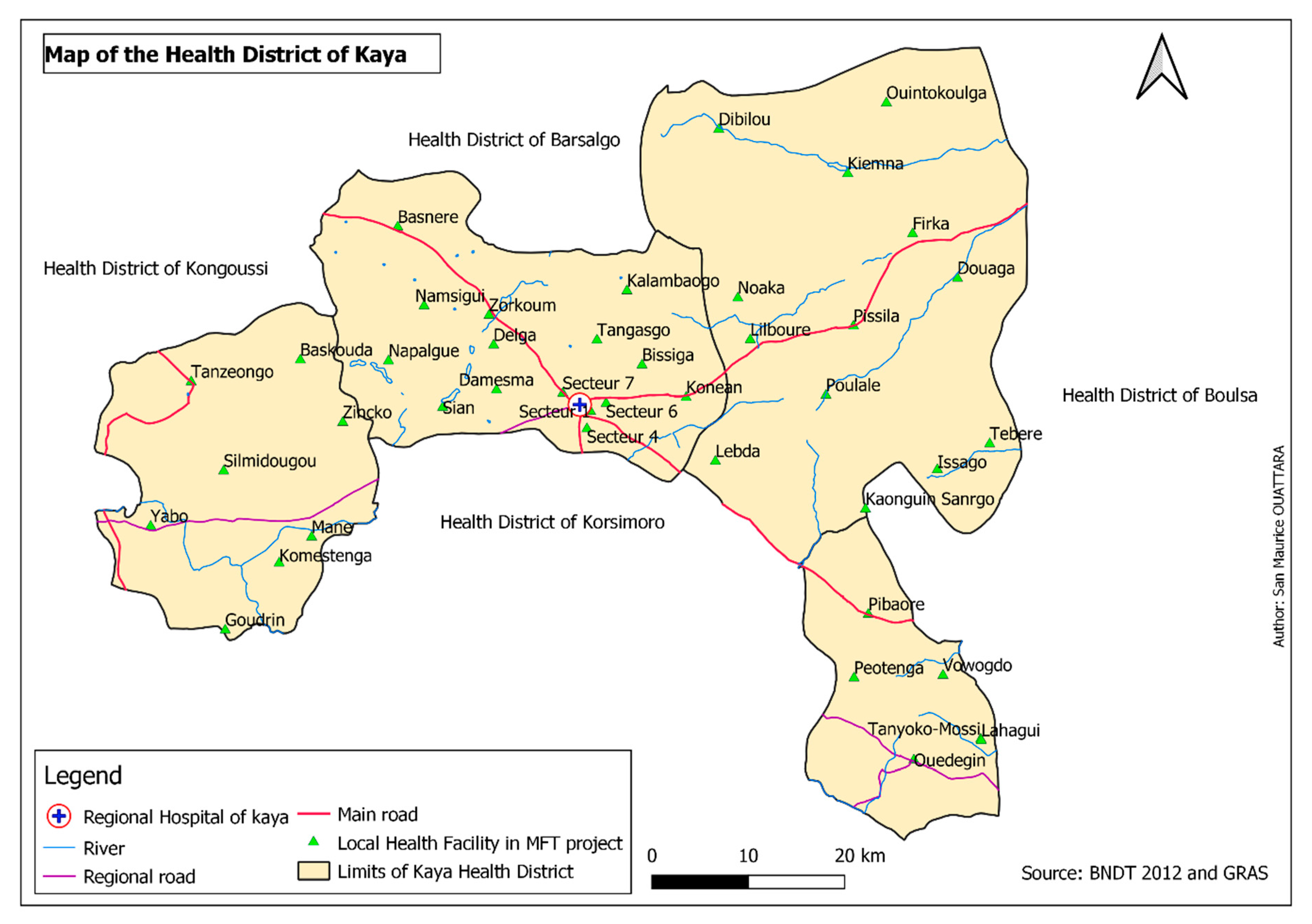

2.1. Study Setting

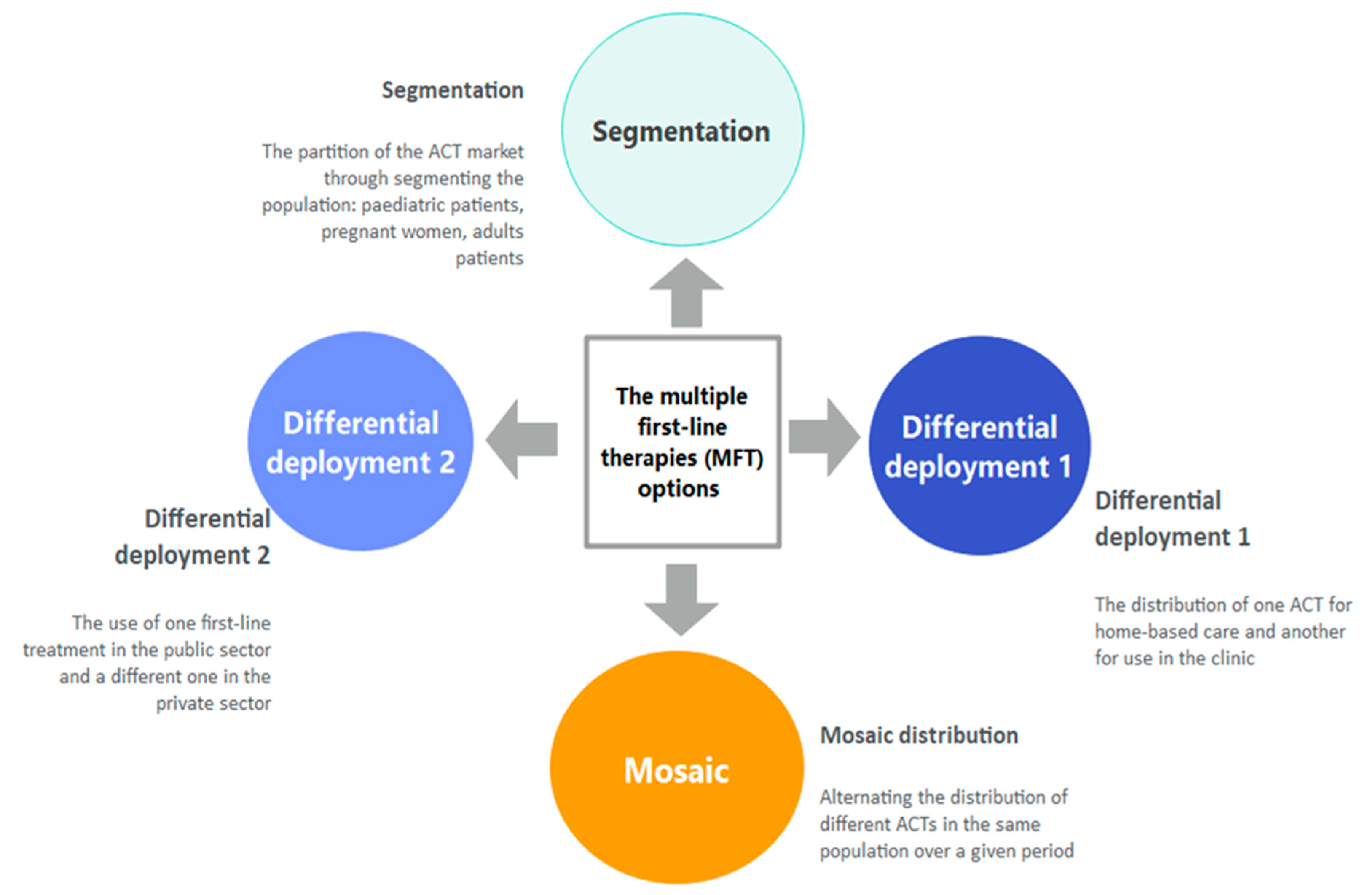

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Description of the Intervention

2.4. Training Cascade of HWs

2.5. Supervision

2.6. Sampling Strategy

2.6.1. Health-Facility Based Survey

2.6.2. Household and Qualitative Surveys

2.7. Sample Size

2.8. Data Collection Procedures

2.9. Outcomes and Explanatory Variables

2.10. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.1.1. HWs Compliance with MFT Strategy Guidelines

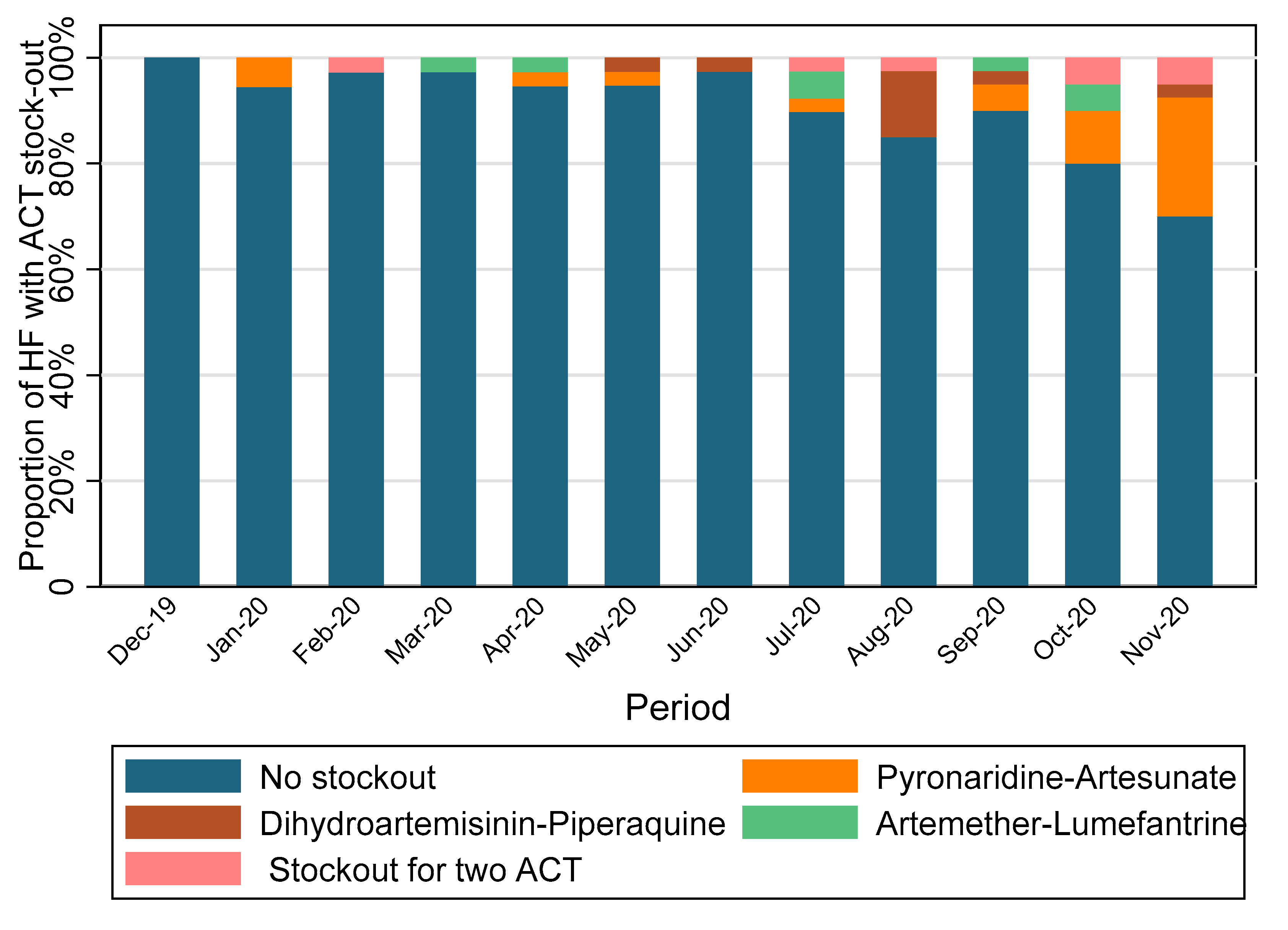

3.1.2. Study Drug Stock Management

3.1.3. Pre- and Post-Intervention Household Surveys

3.1.4. Treatment Side Effects

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.2.1. Health Workers’ and Policymakers’ Opinions on MFT Intervention

“The MFT approach, I think it is good because we have three choices and what is interesting for children under 5, Pyramax is in a sachet [powder], it is in a single dose per day, and easily children accept.”(IDI, Physician)

“For us [HWs], it does not tire us. Because once we have specified, we know that this drug is for this age group and such a treatment for such an age group. Now, you give it according to weight, quantity by weight. And since we were given the posters and put them up in the consultation rooms, I do not think there is a problem for me anyway.”(FGD, head of HF)

“Everyone actually adheres to this new malaria treatment protocol. If you have noticed even since this morning, it is Pyramax, D-artepp except in the case of pregnant women for whom AL is given.”(IDI, health worker)

“This strategy has contributed to better management of uncomplicated malaria. We cannot really say the opposite.”(IDI, health worker)

“This is a good strategy. I think it is new in our country. It is an experience. Thank God! Burkina Faso has given itself the power to absorb this new strategy. I followed the topic from the beginning to the end, from the training until we also report it. I think it is a good strategy”(IDI, Policymaker, NMCP)

“It is a good approach; people have bought in.”(IDI, Health authority, Head of Kaya HD)

3.2.2. Community Acceptability of the Intervention

“These are good medicines [study drugs]; we appreciate the medicines we are given. They are effective.”(FGD, Mothers of children under 5)

“In any case, the product [new product] treats well. In the meantime, my child had malaria, and I went to the hospital, they gave me the prescription, and I took the products, and when I gave it to the child, he quickly recovered his health.”(FGD, adult men)

3.2.3. Challenges in Implementing MFT Strategy

“In the meantime, there was stock out for D-artepp, so we had to switch to AL.”(IDI, Physician)

“Unfortunately, several shortcomings were noted because some [local drug store managers] did not know what target to give. They did not know what was the target that was concerned in this study, what are the different prescription modalities.”(IDI, Policymaker, NMCP)

“I went to the hospital last time and the drug was stocked out. They gave me a prescription and told me to go to town to buy it. I said I could not because my husband is not here. It was the doctor himself who took my prescription to go to the city to get the medicine and come back.”(FGD, Mothers of children under 5)

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2022; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Ministère de la Santé. Secrétariat Général, Direction Générale des Etudes et des Statistiques Sectorielles, Burkina Faso. Annuaire Statistique 2020. Available online: https://www.sante.gov.bf/fileadmin/user_upload/storages/annuaire_statistique_ms_2020_signe.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Trape, J.F. The public health impact of chloroquine resistance in Africa. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2001, 64 (Suppl. 1–2), 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Partnership to Roll Back Malaria. Antimalarial Drug Combination Therapy: Report of a WHO Technical Consultation, 4–5 April 2001. World Health Organization. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66952 (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Rasmussen, C.; Alonso, P.; Ringwald, P. Current and emerging strategies to combat antimalarial resistance. Expert. Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2022, 20, 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministère de la Santé. PNLP, Directives Nationales Pour la Prise en Charge du Paludisme Dans les Formations Sanitaires du Burkina Faso. Available online: http://data.sante.gov.bf/legisante/uploads/DIRECTIVES_PEC_PALU_2017_LLV.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Ministère de la Santé. PNLP, Directives Nationales Pour la Prise en Charge du Paludisme Dans les Formations Sanitaires du Burkina Faso. Available online: http://data.sante.gov.bf/legisante/uploads/Directives-2021_PEC_Palu_VF_.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Sagara, I.; Beavogui, A.H.; Zongo, I.; Soulama, I.; Borghini-Fuhrer, I.; Fofana, B.; Camara, D.; Some, A.F.; Coulibaly, A.S.; Traore, O.B.; et al. Safety and efficacy of re-treatments with pyronaridine-artesunate in African patients with malaria: A substudy of the WANECAM randomised trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West African Network for Clinical Trials of Antimalarial, D. Pyronaridine-artesunate or dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine versus current first-line therapies for repeated treatment of uncomplicated malaria: A randomised, multicentre, open-label, longitudinal, controlled, phase 3b/4 trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 1378–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duparc, S.; Borghini-Fuhrer, I.; Craft, C.J.; Arbe-Barnes, S.; Miller, R.M.; Shin, C.S.; Fleckenstein, L. Safety and efficacy of pyronaridine-artesunate in uncomplicated acute malaria: An integrated analysis of individual patient data from six randomized clinical trials. Malar. J. 2013, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization GMP. Status Report on Artemisinin Resistance. 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/status_rep_artemisinin_resistance_jan2014.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- Dondorp, A.M.; Nosten, F.; Yi, P.; Das, D.; Phyo, A.P.; Tarning, J.; Lwin, K.M.; Ariey, F.; Hanpithakpong, W.; Lee, S.J.; et al. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noedl, H.; Se, Y.; Schaecher, K.; Smith, B.L.; Socheat, D.; Fukuda, M.M. Evidence of artemisinin-resistant malaria in western Cambodia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 2619–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phyo, A.P.; Nkhoma, S.; Stepniewska, K.; Ashley, E.A.; Nair, S.; McGready, R.; ler Moo, C.; Al-Saai, S.; Dondorp, A.M.; Lwin, K.M.; et al. Emergence of artemisinin-resistant malaria on the western border of Thailand: A longitudinal study. Lancet 2012, 379, 1960–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanh, N.V.; Thuy-Nhien, N.; Tuyen, N.T.; Tong, N.T.; Nha-Ca, N.T.; Dong, L.T.; Quang, H.H.; Farrar, J.; Thwaites, G.; White, N.J.; et al. Rapid decline in the susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum to dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine in the south of Vietnam. Malar. J. 2017, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaratunga, C.; Sreng, S.; Suon, S.; Phelps, E.S.; Stepniewska, K.; Lim, P.; Zhou, C.; Mao, S.; Anderson, J.M.; Lindegardh, N.; et al. Artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in Pursat province, western Cambodia: A parasite clearance rate study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyaw, M.P.; Nyunt, M.H.; Chit, K.; Aye, M.M.; Aye, K.H.; Aye, M.M.; Lindegardh, N.; Tarning, J.; Imwong, M.; Jacob, C.G.; et al. Reduced susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum to artesunate in southern Myanmar. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imwong, M.; Hien, T.T.; Thuy-Nhien, N.T.; Dondorp, A.M.; White, N.J. Spread of a single multidrug resistant malaria parasite lineage (PfPailin) to Vietnam. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 1022–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uwimana, A.; Legrand, E.; Stokes, B.H.; Ndikumana, J.M.; Warsame, M.; Umulisa, N.; Ngamije, D.; Munyaneza, T.; Mazarati, J.B.; Munguti, K.; et al. Emergence and clonal expansion of in vitro artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum kelch13 R561H mutant parasites in Rwanda. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1602–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balikagala, B.; Fukuda, N.; Ikeda, M.; Katuro, O.T.; Tachibana, S.I.; Yamauchi, M.; Opio, W.; Emoto, S.; Anywar, D.A.; Kimura, E.; et al. Evidence of Artemisinin-Resistant Malaria in Africa. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gansane, A.; Moriarty, L.F.; Menard, D.; Yerbanga, I.; Ouedraogo, E.; Sondo, P.; Kinda, R.; Tarama, C.; Soulama, E.; Tapsoba, M.; et al. Anti-malarial efficacy and resistance monitoring of artemether-lumefantrine and dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine shows inadequate efficacy in children in Burkina Faso, 2017–2018. Malar. J. 2021, 20, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C.; Ringwald, P. Is there evidence of anti-malarial multidrug resistance in Burkina Faso? Malar. J. 2021, 20, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boni, M.F.; Smith, D.L.; Laxminarayan, R. Benefits of using multiple first-line therapies against malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 14216–14221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Olliaro, P.; Dondorp, A.M.; Baird, J.K.; Lam, H.M.; Farrar, J.; Thwaites, G.E.; White, N.J.; Boni, M.F. Optimum population-level use of artemisinin combination therapies: A modelling study. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, e758–e766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boni, M.F.; White, N.J.; Baird, J.K. The Community As the Patient in Malaria-Endemic Areas: Preempting Drug Resistance with Multiple First-Line Therapies. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1001984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antao, T.; Hastings, I. Policy options for deploying anti-malarial drugs in endemic countries: A population genetics approach. Malar. J. 2012, 11, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shretta, R. Operational Challenges of Implementing Multiple First-Line Therapies for Malaria in Endemic Countries; Management Sciences for Health: Arlington, VA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de la Santé. Secrétariat Général, Direction Générale des Etudes et des Statistiques Sectorielles, Burkina Faso. Annuaire Statistique 2018. Available online: http://cns.bf/IMG/pdf/annuaire_ms_2018.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Siribie, M.; Tchouatieu, A.M.; Soulama, I.; Kabore, J.M.T.; Nombre, Y.; Hien, D.; Kiba Koumare, A.; Barry, N.; Baguiya, A.; Hema, A.; et al. Protocol for a quasi-experimental study to assess the feasibility, acceptability and costs of multiple first-lines artemisinin-based combination therapies for uncomplicated malaria in the Kaya health district, Burkina Faso. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e040220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabore, J.M.T.; Siribie, M.; Hien, D.; Soulama, I.; Barry, N.; Nombre, Y.; Dianda, F.; Baguiya, A.; Tiono, A.B.; Burri, C.; et al. Attitudes, practices, and determinants of community care-seeking behaviours for fever/malaria episodes in the context of the implementation of multiple first-line therapies for uncomplicated malaria in the health district of Kaya, Burkina Faso. Malar. J. 2022, 21, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druetz, T.; Bila, A.; Bicaba, F.; Tiendrebeogo, C.; Bicaba, A. Free healthcare for some, fee-paying for the rest: Adaptive practices and ethical issues in rural communities in the district of Boulsa, Burkina Faso. Glob. Bioeth. 2021, 32, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- President’s Malaria Initiative. Burkina Faso Malaria Operational Plan FY 2018. Available online: https://d1u4sg1s9ptc4z.cloudfront.net/uploads/2021/03/fy-2018-burkina-faso-malaria-operational-plan.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Bonko, M.D.A.; Kiemde, F.; Tahita, M.C.; Lompo, P.; Some, A.M.; Tinto, H.; van Hensbroek, M.B.; Mens, P.F.; Schallig, H. The effect of malaria rapid diagnostic tests results on antimicrobial prescription practices of health care workers in Burkina Faso. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2019, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpimbaza, A.; Babikako, H.; Rutazanna, D.; Karamagi, C.; Ndeezi, G.; Katahoire, A.; Opigo, J.; Snow, R.W.; Kalyango, J.N. Adherence to malaria management guidelines by health care workers in the Busoga sub-region, eastern Uganda. Malar. J. 2022, 21, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Boyle, S.; Bruxvoort, K.J.; Ansah, E.K.; Burchett, H.E.D.; Chandler, C.I.R.; Clarke, S.E.; Goodman, C.; Mbacham, W.; Mbonye, A.K.; Onwujekwe, O.E.; et al. Patients with positive malaria tests not given artemisinin-based combination therapies: A research synthesis describing under-prescription of antimalarial medicines in Africa. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hien, D.; Kabore, J.M.T.; Siribie, M.; Soulama, I.; Barry, N.; Baguiya, A.; Tiono, A.B.; Tchouatieu, A.M.; Sirima, S.B. Stakeholder perceptions on the deployment of multiple first-line therapies for uncomplicated malaria: A qualitative study in the health district of Kaya, Burkina Faso. Malar. J. 2022, 21, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, D.; Gouws, E.; Sach, M.; Karim, S.S. Effect of removing user fees on attendance for curative and preventive primary health care services in rural South Africa. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001, 79, 665–671. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, V.L.; Terlouw, D.J.; Kapinda, A.; Pace, C.; Richards, E.; Tolhurst, R.; Lalloo, D.G. Perceptions and utilization of the anti-malarials artemether-lumefantrine and dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine in young children in the Chikhwawa District of Malawi: A mixed methods study. Malar. J. 2015, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, N.J.; Pongtavornpinyo, W.; Maude, R.J.; Saralamba, S.; Aguas, R.; Stepniewska, K.; Lee, S.J.; Dondorp, A.M.; White, L.J.; Day, N.P. Hyperparasitaemia and low dosing are an important source of anti-malarial drug resistance. Malar. J. 2009, 8, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millogo, O.; Doamba, J.E.O.; Sie, A.; Utzinger, J.; Vounatsou, P. Constructing a malaria-related health service readiness index and assessing its association with child malaria mortality: An analysis of the Burkina Faso 2014 SARA data. BMC Public. Health 2021, 21, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Segment I: Children < 5 Years | Segment II: 5 Years and above | Segment III: Pregnant Women | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | |

| Patients age group | 905 (45.1) | 1012 (50.4) | 91 (4.5) | 2008 (100) |

| Mean age (SD) | 1.85 (1.3) | 18.7 (15.7) | 24.5 (6.1) | 11.4 (14.2) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 459 (50.7) | 464 (45.8) | 0 (0.0) | 923 (46.0) |

| Female | 446 (49.3) | 548 (54.2) | 91 (100.0) | 1085 (54.0) |

| Residence area | ||||

| Rural | 568 (62.8) | 591 (58.4) | 42 (46.2) | 1201 (59.8) |

| Urban | 337 (37.2) | 421 (41.6) | 49 (53.8) | 807 (40.2) |

| Distance travelled for care | ||||

| <5 km | 620 (68.4) | 727 (71.9) | 68 (74.7) | 1415 (70.5) |

| 5–10 km | 160 (17.7) | 120 (11.9) | 7 (7.7) | 287 (14.3) |

| >10 km | 126 (13.9) | 164 (16.2%) | 16 (17.6) | 306 (15.2) |

| Segment I: Children <5 Years | Segment II: Individuals ≥5 Years | Segment III: Pregnant Women | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | |

| HW performance in testing febrile patients for malaria | ||||

| Malaria RDT test performed | N = 906 | N = 1011 | N = 91 | N = 2008 |

| Yes | 706 (77.9) | 813 (80.4) | 69 (75.8) | 1588 (79.1) |

| No | 200 (22.1) | 198 (19.6) | 22 (24.2) | 420 (20.9) |

| Malaria RDT result | N = 706 | N = 813 | N = 69 | N = 1588 |

| Positive | 408 (57.8) | 589 (72.5) | 43 (62.3) | 1040 (65.5) |

| Negative | 292 (41.4) | 211 (25.9) | 26 (37.7) | 529 (33.3) |

| Missing information | 6 (0.8) | 13 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 19 (1.2) |

| Treatment of patients | ||||

| RDT positive * | N = 401 | N = 578 | N = 41 | N = 1020 |

| PYR-AS | 347 (86.5) | 28 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 375 (36.8) |

| DHA-PQP | 9 (2.3) | 464 (80.3) | 0 (0.0) | 473 (46.4) |

| AL | 36 (9.0) | 81 (14.0) | 21 (51.2) | 138 (13.5) |

| QUININE | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (43.9) | 18 (1.8) |

| No treatment | 9 (2.2) | 5 (0.9) | 2 (9.9) | 16 (1.6) |

| RDT negative | N = 292 | N = 211 | N = 26 | N = 529 |

| Treated with ACT | 4 (1.4) | 4 (2.0) | 2 (7.7) | 110 (1.9) |

| No treatment | 288 (98.6) | 206 (97.6) | 24 (92.3) | 518 (98.1) |

| RDT not done | N = 200 | N = 198 | N = 22 | N = 420 |

| Treated | 52 (26.0) | 95 (48.0) | 6 (27.3) | 153 (36.4) |

| No treatment | 148 (74.0) | 103 (52.0) | 16 (72.7) | 267 (63.6) |

| HWs compliance with MFT strategy | ||||

| Appropriate ACT given ** | 348 (86.8) | 493 (85.3) | 37 (90.2) | 878 (86.1) |

| Correctly treated *** | 275 (74.1) | 377 (70.5) | 36 (87.8) | 688 (72.7) |

| Adherence to ACT regimen from the household survey | N = 404 | N = 707 | N = 24 | N = 1135 |

| Adhere to 3-days regimen for any ACT | 335 (82.9) | 577 (81.6) | 20 (83.3) | 932 (82.1) |

| Adhere to 3-days regimen for PYR-AS | 296 (85.3) | 16 (84.2) | 0 (0.0) | 312 (85.3) |

| Adhere to 3-days regimen for DHA-PQP | 12 (92.3) | 364 (84.9) | 0 (0.0) | 376 (85.1) |

| Adhere to 3-days regimen for AL | 27 (61.4) | 197 (76.1) | 20 (83.3) | 244 (74.6) |

| Before Intervention | After Intervention | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children < 5 Years | ≥5 Years | Pregnant Women | Total | Children < 5 Years | ≥5 Years | Pregnant Women | Total | |

| Total of participants interviewed | 462 (33.1) | 898 (64.4) | 34 (2.4) | 1394 (100) | 485 (33.5) | 933 (64.4) | 30 (2.1) | 1448 (100) |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male, n (%) | 240 (51.9) | 350 (39.0) | 0 (0.0) | 590 (42.3) | 252 (52.0) | 406 (43.5) | 0 (0.0) | 658 (45.4) |

| Female, n (%) | 222 (48.1) | 548 (61.0) | 34 (100.0) | 804 (57.7) | 232 (48.8) | 514 (55.1) | 30 (100.0) | 776 (53.6) |

| Missing data | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 13 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (1.0) |

| Education level of respondents | ||||||||

| None | 370 (80.1) | 570 (63.5) | 22 (64.7) | 962 (69.0) | 430 (88.7) | 527 (56.5) | 20 (66.7) | 977 (67.5) |

| Informal education | 35 (7.6) | 72 (8.0) | 4 (11.8) | 111 (8.0) | 9 (1.9) | 36 (3.9) | 2 (6.7) | 47 (3.3) |

| Primary school | 27 (5.8) | 150 (16.7) | 4 (11.8) | 181 (13.0) | 15 (3.1) | 224 (24.0) | 4 (13.3) | 243 (16.8) |

| Secondary and higher | 18 (3.9) | 98 (10.9) | 4 (11.8) | 120 (8.6) | 17 (3.5) | 132 (14.1) | 4 (13.3) | 153 (10.6) |

| Missing data | 12 (2.6) | 8 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (1.4) | 14 (2.9) | 14 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 28 (1.9) |

| Occupation of respondents | ||||||||

| Farmer | 374 (81.0) | 666 (74.2) | 23 (67.7) | 1063 (76.3) | 368 (75.9) | 608 (65.2) | 18 (60.0) | 994 (68.6) |

| Housewife | 50 (10.8) | 47 (5.2) | 5 (14.7) | 102 (7.3) | 93 (19.2) | 235 (25.2) | 11 (36.7) | 339 (23.4) |

| Employee/Merchant | 25 (5.4) | 71 (7.9) | 3 (8.8) | 99 (7.1) | 12 (2.5) | 40 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 52 (3.6) |

| Student | 4 (0.9) | 54 (6.0) | 2 (5.9) | 60 (4.3) | 2 (0.4) | 17 (1.8) | 1 (3.3) | 20 (1.4) |

| Others | 7(1.5) | 27 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 34 (2.4) | 7 (1.4) | 26 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 33 (2.3) |

| Missing data | 2 (0.4) | 33 (3.7) | 1 (2.9) | 36 (2.6) | 3 (0.6) | 7 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (0.7) |

| Household size | ||||||||

| ≤6 | 109 (23.6) | 216 (24.1) | 16 (47.1) | 341 (24.5) | 156 (32.2) | 237 (25.4) | 8 (26.7) | 401 (27.7) |

| >6 | 353 (76.4) | 682 (75.9) | 18 (52.9) | 1053 (75.5) | 329 (67.8) | 696 (74.6) | 22 (73.3) | 1047 (72.3) |

| Before Intervention | After Intervention | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children < 5 Years | ≥5 Years | Pregnant Women | Total | Children < 5 Years | ≥5 Years | Pregnant Women | Total | |

| Total of participants interviewed | 432 (33.5) | 898 (64.4) | 34 (2.4) | 1394 (100) | 485 (33.5) | 933 (64.4) | 30 (2.1) | 1448 (100) |

| Care-seeking behaviours | ||||||||

| Sought care, n (%) | 454 (98.3) | 880 (98.0) | 32 (94.1) | 1366 (98.0) | 480 (99.0) | 913 (97.9) | 30 (100) | 1423 (98.3) |

| Care-seeking within 24 h, n (%) | 311 (68.5) | 573 (65.1) | 20 (62.5) | 904 (66.5) | 256 (53.3) | 487 (53.3) | 10 (33.3) | 753 (54.3) |

| Sources of providers for care | ||||||||

| Public health facilities, n (%) | 384 (84.6) | 570 (64.8) | 28 (87.5) | 982 (72.0) | 407 (84.8) | 693 (76.0) | 29 (96.7) | 1129 (79.4) |

| Private HF/NGO, n (%) | 3 (0.6) | 57 (6.5) | 1 (3.1) | 61 (4.5) | 9 (1.9) | 18 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 27 (1.9) |

| Community health workers, n (%) | 25 (5.5) | 102 (11.6) | 2 (6.3) | 129 (9.5) | 32 (6.7) | 63 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | 95 (6.7) |

| Family stock, n (%) | 26 (5.7) | 53 (6.0) | 0 (0.0) | 79 (5.8) | 20 (4.2) | 59 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 79 (5.6) |

| Traditional healer, n (%) | 7 (1.4) | 11 (2.4) | 1 (3.1) | 32 (2.3) | 7 (1.5) | 37 (4.1) | 0 (0.0) | 44 (3.1) |

| Private pharmacy, n (%) | 2 (0.4) | 9 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 40 (2.9) | 2 (0.4) | 24 (2.6) | 1 (3.3) | 27 (1.9) |

| Street vendor, n (%) | 5 (1.1) | 13 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 35 (2.6) | 3 (0.6) | 14 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (1.2) |

| Malaria RDT test performed and treatment practices | ||||||||

| Tested for malaria, n (%) | 348 (75.3) | 619 (68.9) | 25 (73.5) | 992 (71.2) | 424 (87.6) | 720 (77.6) | 27 (93.1) | 1171 (81.3) |

| Positive malaria test, n (%) | 326 (94.2) | 610 (98.7) | 22 (88.0) | 958 (96.9) | 408 (99.0) | 707 (99.2) | 25 (92.6) | 1140 (98.9) |

| Treated with ACT from any providers, n (%) | 319 (71.9) | 659 (77.3) | 15 (48.4) | 993 (74.8) | 414 (85.4) | 726 (77.8) | 24 (80.0) | 1164 (80.4) |

| Malaria treatment advice given to patient, n (%) | 311 (98.4) | 640 (98.3) | 15 (100.0) | 966 (98.4) | 400 (97.6) | 699 (98.6) | 24 (100.0) | 1123 (98.3) |

| Adherence to 3-day ACT treatment regimen, n (%) | 244 (77.2) | 295 (87.8) | 12 (80.0) | 830 (84.3) | 335 (82.9) | 577 (81.6) | 20 (83.3) | 932 (82.1) |

| PYR-AS (n = 308) | DHA-PQP (n = 374) | AL (n = 267) | Total (n = 949) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any adverse event | 25 (8.1) | 35 (9.4) | 39 (14.6) | 99 (10.4) |

| Vomiting | 11 (3.6) | 9 (2.4) | 17 (6.4) | 37 (3.9) |

| Pruritus | 3 (1.0) | 5 (1.3) | 5 (1.9) | 13 (1.4) |

| Anorexia | 1 (0.3) | 7 (1.9) | 3 (1.2) | 11 (1.2) |

| Diarrhoea | 3 (1.0) | 3 (0.8) | 3 (1.1) | 9 (1.0) |

| Somnolence | 3 (1.0) | 3 (0.8) | 3 (1.1) | 9 (1.0) |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 5 (0.5) |

| Headache | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.5) | 4 (0.4) |

| Other | 3 (1.0) | 5 (1.3) | 3 (1.1) | 11 (1.2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaboré, J.M.T.; Siribié, M.; Hien, D.; Soulama, I.; Barry, N.; Baguiya, A.; Tiono, A.B.; Burri, C.; Tchouatieu, A.-M.; Sirima, S.B. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Strategy Deploying Multiple First-Line Artemisinin-Based Combination Therapies for Uncomplicated Malaria in the Health District of Kaya, Burkina Faso. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8040195

Kaboré JMT, Siribié M, Hien D, Soulama I, Barry N, Baguiya A, Tiono AB, Burri C, Tchouatieu A-M, Sirima SB. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Strategy Deploying Multiple First-Line Artemisinin-Based Combination Therapies for Uncomplicated Malaria in the Health District of Kaya, Burkina Faso. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2023; 8(4):195. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8040195

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaboré, Jean Moïse Tanga, Mohamadou Siribié, Denise Hien, Issiaka Soulama, Nouhoun Barry, Adama Baguiya, Alfred B. Tiono, Christian Burri, André-Marie Tchouatieu, and Sodiomon B. Sirima. 2023. "Feasibility and Acceptability of a Strategy Deploying Multiple First-Line Artemisinin-Based Combination Therapies for Uncomplicated Malaria in the Health District of Kaya, Burkina Faso" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 8, no. 4: 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8040195

APA StyleKaboré, J. M. T., Siribié, M., Hien, D., Soulama, I., Barry, N., Baguiya, A., Tiono, A. B., Burri, C., Tchouatieu, A.-M., & Sirima, S. B. (2023). Feasibility and Acceptability of a Strategy Deploying Multiple First-Line Artemisinin-Based Combination Therapies for Uncomplicated Malaria in the Health District of Kaya, Burkina Faso. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 8(4), 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8040195