Circular Policy: A New Approach to Vector and Vector-Borne Diseases’ Management in Line with the Global Vector Control Response (2017–2030)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Discussion

- (A)

- Identified Sectors and fields of expertise involved in Vector and/or VBDs prevention, control, and treatment

- Political commitment from parties: can be the driving force that will embark the management cycle of an integrated management plan. Endorsement and support by governing authorities is a necessary step towards the implementation of a successful IVM strategy [2].

- International and national policies and legislations: this is pivotal to the creation of sound strategies and their subsequent enforcement. Sub-national levels and local governments must follow guidance documents (policies created by governmental bodies that interpret laws and regulations) to implement the national IVM strategy. In some countries the private sector is recruited in the battle of vector and VBD control and can often follow organizational policies (formal policies adopted by businesses, organizations, and non-governmental entities) that address how they operate, and how may impact their employees, members, volunteers etc. [53,54]. International regulations are succeeded into national laws of the signee parties, e.g., International Health Regulations [55], European Directives and regulations apply for all EU Member States, and Communicable Diseases Laws for each nation are applied during vector and VBD control activities.

- Institution enforcement—Managerial aspect [56]: the key elements of the IVM strategy are managed; competent authorities are assigned with clear goals and targets to manage the prevention, control and treatment of VBDs.

- Institution enforcement—Technical facilities/infrastructure/staff [2]: the managerial aspect of the IVM cannot function without the strengthening of technical facilities, infrastructure, and staff, and is an inclusive process.

- Intrasectoral and intersectoral collaboration [2]: since each sector and field of expertise in IVM depend on the efforts and results that each has, it is crucial to have a transparency of actions, reporting, and intersectoral meetings to avoid the overlapping of efforts or gaps in implemented actions. This is achieved with the formation of coordinating committees with regular meetings and the exchange of information on recognized opportunities and challenges, in order to achieve Best Practice Management. In turn, meetings with subcommittee representatives and relevant governmental committees should take place, to inform and report on the progress. Reviewing and evaluating of all activities can be performed annually and action plans may be amended if needed based on the assessed needs and gaps. After the primary evaluation and reporting, the assigned overarching authority retrieves financial resources for the activities and allocates the required funds to each competent sector/department/division. Since vectors and VBDs know no borders, collaborations with other nations when shared interests and resources are at risk, these can be safeguarded through international agreements.

- Data Sharing [2]: this section cannot be enforced without the prior strengthening of institution management and infrastructure and without intersectoral cooperation. It concerns the collection of data (e.g., surveillance and monitoring data); recording of data; application of data systems; reporting of data to higher level officers and/or committees and sharing data with all involved stakeholders and the public.

- Evaluation of efforts: evaluation of a national plan or program and political commitment/policy are among the most important pillars for integrated implementation. What is a plan good for, when it is not performing as it should or is not adaptable to seasonal, social economic and/or capacity needs of each involved level? An evaluation framework and the selection of evaluators (evaluating authorities) must be set prior to the plan’s implementation and be specific to the plan’s intended efforts (specific metrics/indicators) to achieve the desired result. This action is often overlooked or not set from the beginning, resulting in the blindfolded intensification of interventions (physical, chemical, biological) when the desired outcomes are not achieved.

- Why is it necessary: to ensure the fulfillment of the key principles of IVM and guide public health activities i.e., decision-making processes based on scientific data analysis, social equity from the specific actions/measures, effective performance of the involved sectors, and establishing efforts based on the desired result and accountability [57].

- How is this achieved [58,59]: by setting feedback systems and practical evaluations, ensuring learning and the further improvement of the strategic plan. Evaluations are conducted routinely to provide valid and detailed information to the Inter-Ministerial Steering Committee (overarching authority) to manage and effectively implement the national vector control program. For an evaluation framework to be developed, contribution is required from evaluation experts, directors and staff, governmental officials, independent control associates, researchers, and institutions involved in vector research. Furthermore, impact assessment surveys for vector control programs must include evaluation systems to identify and analyze potential adverse effects (environmental impacts on ecosystems and /or other beneficial species), which may require policy adjustment in order to be avoided in the future and/or mitigated.

- 8.

- Overarching authority: an overarching authority (i.e., ISC) coordinates actions, allocates responsibilities, overviews activities, and evaluates the overall results. It is often recommended that all governmental bodies having jurisdiction in this field are included in the established overarching authority. However, the overarching authority members are not exclusively limited to higher administration levels. Representatives from all relative management working groups are important to participate in the authority, as they are competent to provide advice, data, scientific information, and insight on the program’s processes and outcomes [2].

- 9.

- Communication, awareness, mobilization, education, and engagement [61]: this field is for planning the communication of a new or amended national policy and/or strategy and is performed at two different levels: the sectorial level, between the ISC and the subnational, academic, institutional level, and the private sector, and to the public, which is the general population. For a successful communication strategy, setting objectives, planning, and developing logical and rational interventions and measurements (indicators) of said communication activity—either being complex (i.e., campaigns, workshops, training) or single (i.e., conferences, newsletters, websites, public relations events, press events, social media, smartphone applications, publications etc.) interventions—is crucial [61].

- 10.

- Financial resources: sufficient funding is necessary to achieve the above. Managerial efforts involve expertized personnel, specialized equipment, sound infrastructure, and procured services. Dedicated funding to all sectors with appropriate resources can secure the outcome of an IVM strategy [2].

- (B)

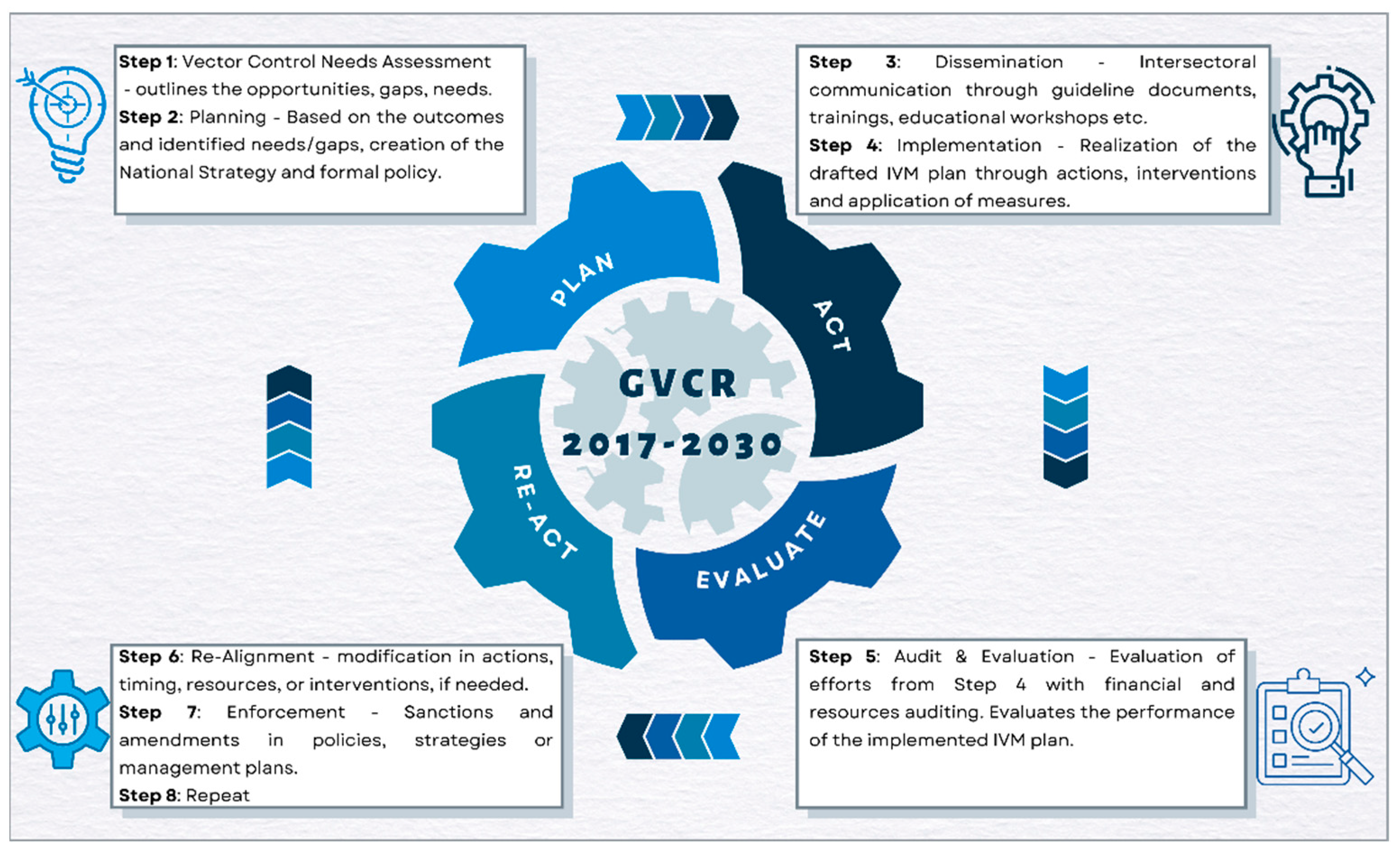

- Circular Policy Approach—Suggested Workflow to Achieve Optimum Implementation Results of an IVM

- (A)

- Plan

- Vector Research Sub-committee, responsible for coordinating activities regarding vector research, surveillance, and monitoring. An annual report on the results and required funds can be created submitted to the competent authority for approval.

- VBD and Public Health Sub-committee can be responsible for the coordinated activities regarding VBDs and public health issues related to vector communicable diseases.

- VBD Wildlife—Environmental Health Sub-committee. VBDs can affect animals as much as humans and both enzootic and zoonotic diseases may later pose a threat for human health as well. It can be responsible for coordinating research studies and the surveillance and monitoring of wildlife populations that are at risk of VBDs, as well as domesticated animals (for Dirofillaria spp., leishmaniasis etc.) and livestock animals (equine encephalitis etc.).

- Biocides’ Regulations Coordinating Sub-committee to oversee all relevant procedures of the regulating, authorizing, and licensing biocides/control—the storage and transport, distribution, and repackaging of chemicals/regulative, importing, exporting, circulating, storing, and repackaging activities of vector control biocides substances for public health.

- Implementation Sub-committee, where all vector control efforts (measures and interventions) should be managed. After consulting with the Vector Research Sub-committee, semester programs can be drafted allocating vector control activities and areas to be treated with physical, biological, or chemical means. The application of biocides can be conducted based on these programs for all vector species targeted and specific, minimizing fruitless actions and environmental impacts.

- Public Engagement Sub-Committee, where communication specialists are suggested to be involved, especially when communicating with the public, to coordinate all involved sectors in preparing publications, press releases, and dissemination of informative material, which is essential for public engagement. Furthermore, it is suggested to be responsible for the creation and keeping of a Scientific Registry of vector and entomological experts.

- (B)

- Acting

- (C)

- Evaluating

- (D)

- Reacting

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Global Vector Control Response 2017–2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Framework for a National Vector Control Needs Assessment; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Position Statement on Integrated Vector Management; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fouque, F.; Reeder, J.C. Impact of past and on-going changes on climate and weather on vector-borne diseases transmission: A look at the evidence. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2019, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beard, C.B.; Eisen, R.J.; Barker, C.M.; Garofalo, J.F.; Hahn, M.; Hayden, M.; Monaghan, A.J.; Ogden, N.H.; Schramm, P.J. Vectorborne Diseases. The Impacts of Climate Change on Human Health in the United States: A Scientific Assessment; U.S. Global Change Research Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Chapter 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lakshmi, P.V.M. Environmental Factors: Vector Borne Diseases; PIGMER: Chandigarh, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Parham, P.E.; Waldock, J.; Christophides, G.K.; Hemming, D.; Agusto, F.; Evans, K.J.; Fefferman, N.; Gaff, H.; Gumel, A.; LaDeau, S.; et al. Climate, environmental and socio-economic change: Weighing up the balance in vector-borne disease transmission. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20130551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ortiz, D.I.; Piche-Ovares, M.; Romero-Vega, L.M.; Wagman, J.; Troyo, A. The Impact of Deforestation, Urbanization, and Changing Land Use Patterns on the Ecology of Mosquito and Tick-Borne Diseases in Central America. Insects 2021, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, J.F.; Molyneux, D.H.; Birley, M.H. Deforestation: Effects on vector-borne disease. Parasitology 1993, 106, S55–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waits, A.; Emelyanova, A.; Oksanen, A.; Abass, K.; Rautio, A. Human infectious diseases and the changing climate in the Arctic. Environ. Int. 2018, 121, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, H.A.; Huxley, P.; Elmes, J.; Murray, K.A. Agricultural land-uses consistently exacerbate infectious disease risks in Southeast Asia. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Langevelde, F.; Mondoza, H.R.R.; Matson, K.D.; Esser, H.J.; de Boer, W.F.; Schindler, S. The Link Between Biodiversity Loss and the Increasing Spread of Zoonotic Diseases, Document for the Committee on Environment, Public Health and Food Safety, Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies; European Parliament: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mack, A.; National Academies of Sciences. Global Health Impacts of Vector-Borne Diseases (Workshop) Global Health Impacts of Vector-Borne Diseases: Workshop Summary; National Academies of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brogdon, W. Insecticide Resistance and Vector Control. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 1998, 4, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, H.V.D.; Bezerra, H.S.D.S.; Al-Eryani, S.; Chanda, E.; Nagpal, B.N.; Knox, T.B.; Velayudhan, R.; Yadav, R.S. Recent trends in global insecticide use for disease vector control and potential implications for resistance management. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Manga, L.; Bagayoko, M.; Sommerfeld, J. Climate change and vector-borne diseases: What are the implications for public health research and policy? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20130552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mugisha, A.; McLeod, A.; Percy, R.; Kyewalabye, E. Socio-economic factors influencing control of vector-borne diseases in the pastoralist system of south western Uganda. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2008, 40, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. A Global Brief on Vector-Borne Diseases; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Blas, E. Multisectoral Action Framework for Malaria; United Nation Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Handbook for Integrated Vector Management; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; Available online: Https://Apps.Who.Int/Iris/Handle/10665/44768 (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Martinou, A.F.; Schäfer, S.M.; Mari, R.B.; Angelidou, I.; Erguler, K.; Fawcett, J.; Ferraguti, M.; Foussadier, R.; Gkotsi, T.V.; Martinos, C.F.; et al. A call to arms: Setting the framework for a code of practice for mosquito management in European wetlands. J. Appl. Ecol. 2020, 57, 1012–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; European Food Safety Authority. Field Sampling Methods for Mosquitoes, Sandflies, Biting Midges and ticks: VectorNet Project 2014–2018; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Stockholm, Sweden; European Food Safety Authority: Parma, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Strategic Framework for Integrated Vector Management; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vector Control Advisory Group (VCAG). Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/control-of-neglected-tropical-diseases/overview/vector-control-advisory-committee (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- WHO. Vector Control Interventions Designed to Control Malaria in Complex Humanitarian Emergencies and in Response to Natural Disasters: Preferred Product Characteristics; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- WHO; IAEA. Guidance Framework for Testing the Sterile Insect Technique as a Vector Control Tool against Aedes-Borne Diseases; Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland; International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Norms, Standards and Processes Underpinning Development of WHO Recommendations on Vector Control; Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Equipment for Vector Control, 3rd ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Manual on Environmental Management for Mosquito Control, with Special Emphasis on Malaria Vectors; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Equipment for Vector Control Specification Guidelines, Revised ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Vector Control Response: Progress in Planning and Implementation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Protecting the Health and Safety of Workers in Emergency Vector Control of Aedes Mosquitoes; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Golding, N.; Wilson, A.L.; Moyes, C.L.; Cano, J.; Pigott, D.M.; Velayudhan, R.; Brooker, S.J.; Smith, D.L.; Hay, S.I.; Lindsay, S.W. Integrating vector control across diseases. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- WHO. The Evaluation Process for Vector Control Products; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Keeping the Vector out: Housing Improvements for Vector Control and Sustainable Development; World Health Organization: Geneva, Swizterland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Organisation of Vector Surveillance and Control in Europe; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chaskopoulou, A.; Braks, M.; van Bortel, W.; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; European Food Safety Authority. Vector Control Practices and Strategies against West Nile Virus; European Food Safety Authority: Parma, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Semenza, J.C.; Zeller, H. Integrated surveillance for prevention and control of emerging vector-borne diseases in Europe. Eurosurveillance 2014, 19, 20757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; European Food Safety Authority. The Importance of Vector Abundance and Seasonality—Results from an Expert Consultation; Stockholm and Parma: ECDC and EFSA; European Food Safety Authority: Parma, Italy, 2018; pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. A Spatial Modelling Method for Vector Surveillance; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Guidelines for the Surveillance of Native Mosquitoes in Europe; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Guidelines for the Surveillance of Invasive Mosquitoes in Europe; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Guidelines for Presentation of Surveillance Data; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, J. Core Competencies in Applied Infectious Disease Epidemiology in Europe Core Competencies in Applied Infectious Disease Epidemiology in Europe Ii; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Manuals and Protocols. Available online: https://www.iaea.org/topics/insect-pest-control/manuals-and-protocols?page=2 (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Gbolade, A.A.; Lukwa, N.; Kalenda, D.T.; Boëte, C.H.J.J.; Knols, B.G.J. Guidelines for studies on plant-based vector control agents. In Traditional Medicinal Plants and Malaria; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; pp. 479–503. [Google Scholar]

- Bouyer, J.; Chandre, F.; Gilles, J.; Baldet, T. Alternative vector control methods to manage the Zika virus outbreak: More haste, less speed. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases Selected Articles from the WORLD ANIMAL REVIEW. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/x6538e/X6538E00.htm (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Davies, F.G.; Martin, V. Recognizing Rift Valley Fever. Veter-Ital. 2006, 42, 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tsetse and trypanosomiasis information quarterly. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 1979, 11, 221. [CrossRef]

- Global Mosquito Alert Consortium. Real-Time Targeted Vector Mosquito Monitoring. Available online: https://globalmosquitoalert.com/guides/pillar1/ (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- Global Mosquito Alert Consortium. Vector Mosquito Monitoring via Biodiversity Specimen/DNA Data Sharing. Available online: https://globalmosquitoalert.com/guides/pillar4/ (accessed on 25 April 2022).

- ICLEI—Local Governments for Sustainability. Political Commitment Roadmap for Sustainable Baltic Cities; ICLEI: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Factsheet Drafting Effective Policies; Funded by the Kansas Health Foundation; Public Health Law Center at William Mitchell College of Law: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2014.

- WHO. International Health Regulations (2005); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg, H.; Mutero, C.M.; Ichimori, K. Guidance on Policy-Making for Integrated Vector Management Integrated Vector Management (IVM) Vector Ecology and Management (VEM) Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Monitoring and Evaluation Indicators for Integrated Vector Management. Cataloguing-in-Publication Data; World Health Organization Library: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Framework for Program Evaluation in Public Health. MMWR 1999, 48, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, G. A new evidence framework for health promotion practice. Health Educ. J. 2000, 59, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EVALSED: The Resource for the Evaluation of Socio-Economic Development. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/evaluation/guide/guide_evalsed.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- European Commission. TOOLKIT for the Evaluation of the Communication Activities. European Commission Directorate-General for Communication Unit COMM.D1—Budget, Accounting and Evaluations; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Community ToolBox. Chapter 36. Introduction to Evaluation. Available online: https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/evaluate/evaluation (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- American Veterinary Medical Association. One Health Initiative Task Force. “One Health: A New Professional Imperative”. Available online: https://www.avma.org/sites/default/files/resources/onehealth_final.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2020).

| Organization | Documents | Sector |

|---|---|---|

| WHO | Latest Meetings of the WHO Vector Control Advisory Group [24] | Product developers, innovators, and researchers on the generation of epidemiological data and study designs to enable assessment of the public health value of new vector control interventions |

| Vector control interventions designed to control malaria in complex humanitarian emergencies and in response to natural disasters [25] | ||

| Guidance framework for testing the sterile insect technique as a vector control tool against aedes-borne diseases [26] | ||

| Global vector control response 2017–2030: A strategic approach to tackle vector-borne diseases [1] | National, subnational, regional, and departmental level (i.e., governments and public health agencies, vector control workers) | |

| Norms, standards and processes underpinning development of WHO recommendations on vector control [27] | ||

| Equipment for vector control—Third edition [28] | ||

| Manual on environmental management for mosquito control, with special emphasis on malaria vectors [29] | ||

| Equipment for vector control specification guidelines—Revised edition [30] | ||

| Global vector control response: progress in planning and implementation [31] | ||

| Protecting the health and safety of workers in emergency vector control of Aedes mosquitoes: Interim guidance for vector control and health workers [32] | ||

| Integrating vector control across diseases [33] | ||

| The evaluation process for vector control products [34] | ||

| Framework for a national vector control needs assessment [2] | ||

| Handbook for integrated vector management [20] | ||

| Global Strategic Framework for Integrated Vector Management World Health Organization [23] | ||

| Keeping the vector out: housing improvements for vector control and sustainable development [35] | Communities | |

| ECDC | Organization of vector surveillance and control in Europe [36] | National, subnational, regional, and departmental level (i.e., governments and public health agencies, vector control workers) |

| Vector control practices and strategies against West Nile virus [37] | ||

| Integrated surveillance for prevention and control of emerging vector-borne diseases in Europe [38] | ||

| The importance of vector abundance and seasonality [39] | ||

| A spatial modeling method for vector surveillance [40] | ||

| Organization of vector surveillance and control in Europe [36] | ||

| Guidelines for the surveillance of native mosquitoes in Europe [41] | ||

| Guidelines for the surveillance of invasive mosquitoes in Europe [42] | ||

| Guidelines for presentation of surveillance data [43] | ||

| Field sampling methods for mosquitoes, sandflies, biting midges and ticks [22] | ||

| Core competencies in applied infectious disease epidemiology in Europe [44] | For training needs assessments in public health institutions | |

| IAEA | Insect–pest control: Manuals and protocols [45] | Product developers, innovators, and researchers on the generation of epidemiological data and study designs to enable assessment of the public health value of new vector control interventions |

| Guidelines for Studies on Plant-Based Vector Control Agents. In Traditional Medicinal Plants and Malaria [46] | ||

| Guidance framework for testing the sterile insect technique as a vector control tool against aedes-borne diseases [26] | ||

| Alternative vector control methods to manage the Zika virus outbreak: more haste, less speed [47] | National, subnational, regional, and departmental level (i.e., governments and public health agencies, vector control workers) | |

| FAO | Ticks and tick-borne diseases selected articles from the WORLD ANIMAL REVIEW [48] | For training needs assessments in public health institutions |

| Recognizing Rift Valley Fever [49] | ||

| Tsetse and trypanosomiasis information: Quarterly [50] | ||

| UNE, STIP, ECSA | Real-Time Targeted Vector Mosquito Monitoring Best Practices Guide [51] | Citizen science |

| Vector Mosquito Monitoring Via Biodiversity Specimen/DNA Data Sharing Best Practices Guide [52] | ||

| UNDP | Multisectoral action framework for malaria [19] | National, subnational, regional, and departmental level (i.e., governments and public health agencies, vector control workers) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tourapi, C.; Tsioutis, C. Circular Policy: A New Approach to Vector and Vector-Borne Diseases’ Management in Line with the Global Vector Control Response (2017–2030). Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7070125

Tourapi C, Tsioutis C. Circular Policy: A New Approach to Vector and Vector-Borne Diseases’ Management in Line with the Global Vector Control Response (2017–2030). Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2022; 7(7):125. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7070125

Chicago/Turabian StyleTourapi, Christiana, and Constantinos Tsioutis. 2022. "Circular Policy: A New Approach to Vector and Vector-Borne Diseases’ Management in Line with the Global Vector Control Response (2017–2030)" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 7, no. 7: 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7070125

APA StyleTourapi, C., & Tsioutis, C. (2022). Circular Policy: A New Approach to Vector and Vector-Borne Diseases’ Management in Line with the Global Vector Control Response (2017–2030). Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 7(7), 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed7070125