Active Case Finding for Tuberculosis in India: A Syntheses of Activities and Outcomes Reported by the National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme

Abstract

:1. Introduction

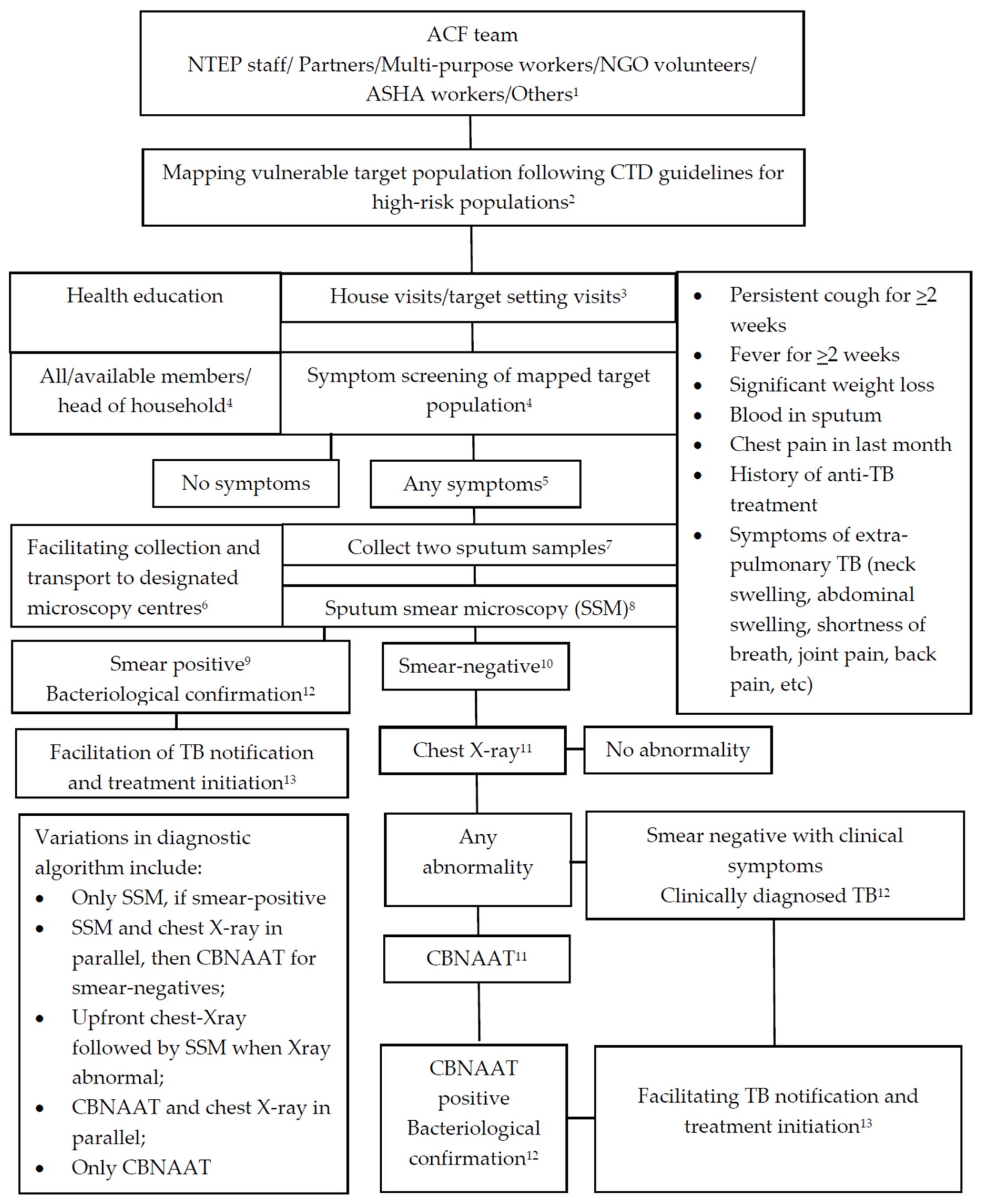

Active Case Finding (ACF) Campaign under the National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Types of Studies

2.2. Participants and ACF Activities

2.3. Types of Outcome Measures

- A description of the ACF programmes and the diagnostic algorithms used to detect TB cases;

- The outcomes of ACF activities, including the number (and proportion) of people: (a) screened from the vulnerable target population mapped; (b) identified with presumptive TB; (c) tested for TB at the district medical/microscopy centres; (d) diagnosed with all forms of TB (positivity rate or yield) through sputum microscopy, chest X-ray and GeneXpert (cartridge-based nucleic acid amplification tests or CBNAAT); (e) initiated on anti-TB treatment (treatment initiation rate) and (f) completing treatment (treatment completion rate, loss to follow up and mortality). From this data, we estimated (g) the number needed to screen (NNS), which is the number of individuals who were screened to identify one person diagnosed with TB. We also sought (h) data on the impact of ACF on TB notification.

- The challenges encountered during the process of community-based ACF.

2.4. Search Methods

2.5. Data Management and Analysiss

3. Results

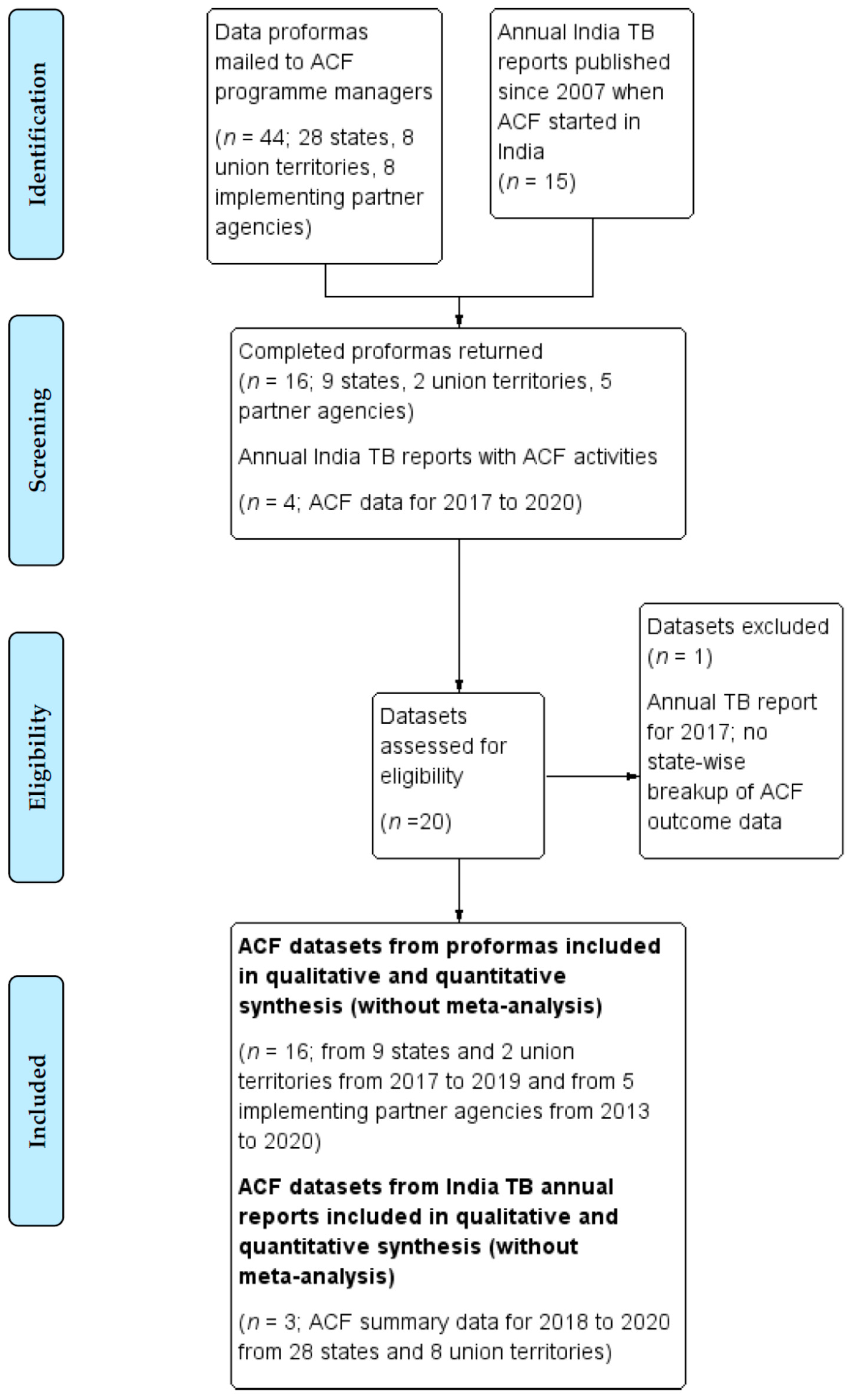

3.1. Respondents

3.2. Overall Data Quality and Completeness

3.3. Details of ACF Activities

3.3.1. Frequency and Duration of ACF Activities

3.3.2. Mapping Vulnerable Populations and Selecting Target Areas

3.3.3. Types of ACF Activities

3.3.4. Personnel Engaged for ACF

3.3.5. Incentives for ACF Personnel and Support for Activities

3.3.6. Diagnostic Algorithms Used

3.4. ACF Activities and Outcomes from Responding State and Union Territories

3.5. ACF Activities Provided by Partner Agencies

3.6. ACF Outcomes for All States and Union Territories in India for 2020

3.7. ACF Outcomes for States and Union Terrritories Compared to the Expected Indicators for ACF Set by the NTEP

3.7.1. Vulnerable Target Population Mapped and Screened

3.7.2. Proportions Undergoing Diagnostic Tests for TB among Those Screened and in Those with Presumptive TB

3.7.3. Diagnostic Algorithms Used and the Proportions Tested with Sputum Smear Microscopy, Chest X-ray and Xpert MTB/Rif (CBNAAT)

3.7.4. Proportions Diagnosed with All Forms of TB (Diagnostic Yield)

3.7.5. Proportions Initiating and Completing Anti-TB Treatment

3.7.6. The Number Needed to Screen (NNS)

3.7.7. The Impact of ACF on TB Notification

3.8. Challenges Faced by Implementors in Implementing ACF

4. Discussion

4.1. The Gaps between the Expected Indicators and Outcomes in India’s ACF Programme

4.2. Implications for Potential Interventions to Improve ACF Outcomes and Efficiency

4.2.1. Improving the Mapping of Vulnerable Populations and Increasing the Uptake of Screening

4.2.2. Better Use of Data Management Systems

4.2.3. Moving beyond Screening for TB Symptoms

4.2.4. Increasing the Diagnostic Yield with ACF

4.3. Limitations of the Review

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/336069/9789240013131-eng.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Ho, J.; Fox, G.J.; Marais, B.J. Passive case finding for tuberculosis is not enough. Int. J. Mycobacteriol. 2016, 5, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. The End TB Strategy; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: http://www.who.int/tb/post2015_TBstrategy.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2020).

- World Health Organization. Systematic Screening for Active Tuberculosis. Principles and Recommendations; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; Available online: https://www.who.int/tb/publications/tbscreening/en/ (accessed on 14 January 2020).

- Fox, G.J.; Barry, S.E.; Britton, W.J.; Marks, G. Contact investigation for tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 41, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golub, J.E.; Mohan, C.I.; Comstock, G.W.; Chaisson, R.E. Active case finding of tuberculosis: Historical perspective and future prospects. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2005, 9, 1183–1203. [Google Scholar]

- Kranzer, K.; Houben, R.M.; Glynn, J.R.; Bekker, L.-G.; Wood, R.; Lawn, S.D. Yield of HIV-associated tuberculosis during intensified case finding in resource-limited settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kranzer, K.; Afnan-Holmes, H.; Tomlin, K.; Golub, J.E.; Shapiro, A.; Schaap, A.; Corbett, E.; Lonnroth, K.; Glynn, J.R. The benefits to communities and individuals of screening for active tuberculosis disease: A systematic review. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2013, 17, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mhimbira, F.A.; Cuevas, L.E.; Dacombe, R.; Mkopi, A.; Sinclair, D. Interventions to increase tuberculosis case detection at primary healthcare or community-level services. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 11, CD011432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chadha, V.; Praseeja, P. Active tuberculosis case finding in India—The way forward. Indian J. Tuberc. 2019, 66, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewade, H.D.; Gupta, V.; Satyanarayana, S.; Pandey, P.; Bajpai, U.N.; Tripathy, J.P.; Kathirvel, S.; Pandurangan, S.; Mohanty, S.; Ghule, V.H.; et al. Patient characteristics, health seeking and delays among new sputum smear positive TB patients identified through active case finding when compared to passive case finding in India. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shewade, H.D.; Gupta, V.; Satyanarayana, S.; Kharate, A.; Sahai, K.; Murali, L.; Kamble, S.; Deshpande, M.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, S.; et al. Active case finding among marginalised and vulnerable populations reduces catastrophic costs due to tuberculosis diagnosis. Glob. Health Action 2018, 11, 1494897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, G.B.; Nguyen, N.V.; Nguyen, P.T.; Nguyen, T.A.; Nguyen, H.B.; Tran, K.H.; Nguyen, S.V.; Luu, K.B.; Tran, D.T.; Vo, Q.T.; et al. Community-wide Screening for Tuberculosis in a High-Prevalence Setting. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1347–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraja, S.B.; Satyanarayana, S.; Shastri, S. Active tuberculosis case finding in India: Need for introspection. Public Health Action 2017, 7, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Central TB Division. National Strategic Plan for Tuberculosis Elimination 2017–2025; Directorate General of Health Services Ministry of Health and Family Welfare: New Delhi, India, 2017.

- Central TB Division. Active TB Case Finding, Guidance document (Updated in June 2017); Directorate General of Health Services Ministry of Health and Family Welfare: New Delhi, India, 2017.

- Nagaraja, B.S.; Thekkur, P.; Satyanarayana, S.; Tharyan, P.; Sagili, K.; Tonsing, J.; Rao, R. Approaches to community-based active case finding for tuberculosis in India: A systematic review. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020199854 (accessed on 3 November 2020).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Central TB Division. India TB Annual Report—2018; Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare: New Delhi, India, 2018.

- Central TB Division. India TB Annual Report—2019; Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare: New Delhi, India, 2019.

- Central TB Division. India TB Annual Report—2020; Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare: New Delhi, India, 2020.

- Central TB Division. India TB Annual Report—2021; Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare: New Delhi, India, 2021.

- Campbell, M.; Katikireddi, S.; Hoffmann, T.; Armstrong, R.; Waters, E.; Craig, P. TIDieR-PHP: A reporting guideline for population health and policy interventions. BMJ 2018, 361, k1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Campbell, M.; McKenzie, J.; Sowden, A.; Katikireddi, S.; Brennan, S.; Ellis, S.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Ryan, R.; Shepperd, S.; Thomas, J.; et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: Reporting guideline. BMJ 2020, 368, l6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Systematic Screening for Active Tuberculosis: An Operational Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/181164/9789241549172_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- World Health Organization. WHO Operational Handbook on Tuberculosis. Module 2: Screening—Systematic Screening for Tuberculosis Disease; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022614 (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Indian Council of Medical Research. Tuberculosis in India—A Sample Survey, 1955–1958; Special Report Series No 34; Indian Council of Medical Research: New Delhi, India, 1959.

- Chadha, V.K. Tuberculosis epidemiology in India: A review. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2005, 9, 1072–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, B.E.; Adinarayanan, S.; Manogaran, C.; Swaminathan, S. Pulmonary tuberculosis among tribals in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J. Med. Res. 2015, 141, 614–623. [Google Scholar]

- Chadha, V.K.; Anjinappa, S.M.; Dave, P.; Rade, K.; Baskaran, D.; Narang, P.; Kolappan, C.; Katoch, K.; Sharma, S.K.; Rao, V.G.; et al. Sub-national TB prevalence surveys in India, 2006–2012: Results of uniformly conducted data analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sathiyamoorthy, R.; Kalaivani, M.; Aggarwal, P.; Gupta, S.K. Prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lung India 2020, 37, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamanewadi, A.N.; Naik, P.R.; Thekkur, P.; Madhukumar, S.; Nirgude, A.S.; Pavithra, M.B.; Poojar, B.; Sharma, V.; Urs, A.P.; Nisarga, B.V.; et al. Enablers and Challenges in the Implementation of Active Case Findings in a Selected District of Karnataka, South India: A Qualitative Study. Tuberc. Res. Treat. 2020, 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Multisectoral Accountability Framework to Accelerate Progress to End Tuberculosis by 2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/tb/publications/MultisectoralAccountability/en (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Satyanarayana, S.; Thekkur, P.; Kumar, A.M.V.; Lin, Y.; Dlodlo, R.A.; Khogali, M.; Zachariah, R.; Harries, A.D. An Opportunity to END TB: Using the Sustainable Development Goals for Action on Socio-Economic Determinants of TB in High Burden Countries in WHO South-East Asia and the Western Pacific Regions. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- André, E.; Rusumba, O.; Evans, C.; Ngongo, P.; Sanduku, P.; Elvis, M.M.; Celestin, H.N.; Alain, I.R.; Musafiri, E.M.; Kabuayi, J.-P.; et al. Patient-led active tuberculosis case-finding in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Bull. World Health Organ. 2018, 96, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuot, S.; Teo, A.K.J.; Cazabon, D.; Sok, S.; Ung, M.; Ly, S.; Choub, S.C.; Yi, S. Acceptability of active case finding with a seed-and-recruit model to improve tuberculosis case detection and linkage to treatment in Cambodia: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teo, A.K.J.; Prem, K.; Tuot, S.; Ork, C.; Eng, S.; Pande, T.; Chry, M.; Hsu, L.Y.; Yi, S. Mobilising community networks for early identification of tuberculosis and treatment initiation in Cambodia: An evaluation of a seed-and-recruit model. ERJ Open Res. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vo, L.N.Q.; Vu, T.N.; Nguyen, H.T.; Truong, T.T.; Khuu, C.M.; Pham, P.Q.; Nguyen, L.H.; Le, G.T.; Creswell, J. Optimizing community screening for tuberculosis: Spatial analysis of localized case finding from door-to-door screening for TB in an urban district of Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0209290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mac, T.H.; Phan, T.H.; Van Nguyen, V.; Dong, T.T.T.; Van Le, H.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Nguyen, T.D.; Codlin, A.J.; Mai, T.D.T.; Forse, R.J.; et al. Optimizing Active Tuberculosis Case Finding: Evaluating the Impact of Community Referral for Chest X-ray Screening and Xpert Testing on Case Notifications in Two Cities in Viet Nam. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onozaki, I.; Law, I.; Sismanidis, C.; Zignol, M.; Glaziou, P.; Floyd, K. National tuberculosis prevalence surveys in Asia, 1990–2012: An overview of results and lessons learned. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2015, 20, 1128–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Xia, Y. Diagnostic Value of Symptom Screening for Pulmonary Tuberculosis in China. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadeer, E.; Fatima, R.; Yaqoob, A.; Tahseen, S.; Haq, M.U.; Ghafoor, A.; Asif, M.; Straetemans, M.; Tiemersma, E.W. Population Based National Tuberculosis Prevalence Survey among Adults (>15 Years) in Pakistan, 2010–2011. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drain, P.K.; Bajema, K.L.; Dowdy, D.; Dheda, K.; Naidoo, K.; Schumacher, S.G.; Ma, S.; Meermeier, E.; Lewinsohn, D.M.; Sherman, D.R. Incipient and Subclinical Tuberculosis: A Clinical Review of Early Stages and Progression of Infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bekken, G.K.; Ritz, C.; Selvam, S.; Jesuraj, N.; Hesseling, A.C.; Doherty, T.M.; Grewal, H.M.S.; Vaz, M.; Jenum, S. Identification of subclinical tuberculosis in household contacts using exposure scores and contact investigations. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Recommendations for Investigating Contacts of Persons with Infectious Tuberculosis in Low- and Middle-Income Countries; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; pp. 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Das, M.; Pasupuleti, D.; Rao, S.; Sloan, S.; Mansoor, H.; Kalon, S.; Hossain, F.N.; Ferlazzo, G.; Isaakidis, P. GeneXpert and Community Health Workers Supported Patient Tracing for Tuberculosis Diagnosis in Conflict-Affected Border Areas in India. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ho, J.; Nguyen, P.T.B.; Nguyen, T.A.; Tran, K.H.; Van Nguyen, S.; Nguyen, N.V.; Nguyen, H.B.; Luu, K.B.; Fox, G.J.; Marks, G. Reassessment of the positive predictive value and specificity of Xpert MTB/RIF: A diagnostic accuracy study in the context of community-wide screening for tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 1045–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassall, A.; van Kampen, S.; Sohn, H.; Michael, J.S.; John, K.R.; Boon, S.D.; Davis, J.L.; Whitelaw, A.; Nicol, M.; Gler, M.T.; et al. Rapid Diagnosis of Tuberculosis with the Xpert MTB/RIF Assay in High Burden Countries: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. PLoS Med. 2011, 8, e1001120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cilloni, L.; Kranzer, K.; Stagg, H.R.; Arinaminpathy, N. Trade-offs between cost and accuracy in active case finding for tuberculosis: A dynamic modelling analysis. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Indicator | Expected Proportion |

|---|---|

| Vulnerable population to be mapped per 1 million population | 11% |

| Number in the mapped target population to be screened | >90% |

| Number with presumptive TB among those screened | 5% |

| Number with presumptive TB patients examined (by smear microscopy, CBNAAT or other investigations) | >95% |

| Number with sputum smear-positive test results | 5% (minimum >2% to 3%) |

| Number of sputum smear-negative TB patients examined by chest X-ray and/or CBNAAT | >90% |

| Number with TB diagnosed among those tested | 5% |

| Number of diagnosed TB patients put on treatment | >95% |

| State/ Union Territory | Year | Target Population Mapped | Numbers Screened (%) | TB Tested in Those with Presumptive TB (%) and among Those Screened [%] | TB Diagnostic Tests | TB Diagnosed (%; 95% CI) | NNS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sputum Positive (%) | X-ray Abnormal (%) | CBNAAT Positive (%) | Anti-TB Treatment Initiated (%) | |||||||

| Andaman & Nicobar | 2017 | 18,526 | 15,040 (81.1) | 11/11 a (100) [0.7] | 11/11 (100) | 1/1 (100) | 10/11 (90.9) | 11 (100; 74.1 to 100) | 1367 | 11 (100) |

| 2018 | 1389 | 46 (3.3) | 31/31 a (100) [67.4] | 1/23 (4.4) | 0/13 (0) | 1/5 (20) | 1 (3.2; 0.6 to 16.2) | 46 | 1 (100) | |

| Andhra Pradesh | 2018 to 2019 | 34,220,840 | 465,223 (1.4) | 55,922/55,922 a (100) [12.0] | 4736/55,922 (8.5) | NA | NA | 4736 (8.5; 8.2 to 8.7) | 98 | NA |

| Bihar | 2017 | 5,650,354 | 3,033,966 (53.7) | NA | 3130/33,754 (9.3) | Nil | Nil | 3130 (9.3; 9.0 to 9.6) | 969 | NA |

| 2018 | 2,722,279 | 1,453,422 (53.4) | NA | 816/24,482 (3.3) | Nil | Nil | 816 (3.3; 3.1 to 3.6) | 1781 | NA | |

| 2019 | 10,298,046 | 6,141,262 (59.6) | 44,858/329,060 (13.6) [0.7] | 2583/31,955 (8.1) | 921/3974 (23.2) | 559/2046 (27.3) | 3200 (7.1; 6.9 to 7.4) | 1919 | NA | |

| Gujarat | 2017 | 14,747,300 | 4,763,436 (32.3) | 37,899/65,059 (58.3) [0.8] | 1331/37,899 (3.5) | 930/6185 (15.0) | Nil | 2261 (6.0; 5.7 to 6.2) | 2106 | NA |

| 2018 | 29,310,663 | 18,452,680 (63.0) | 60,764/79,723 (76.2) [0.3] | 1922/60,764 (3.2) | 1192/15176 (7.9) | 320/4437 (7.2) | 3562 (5.9; 5.7 to 6.1) | 5180 | 1856 (52.1) | |

| 2019 | 59,397,280 | 37,692,373 (63.5) | 77,680/101,304 (76.6) [0.2] | 1889/71,039 (2.7) | 887/20,269 (4.4) | 311/11,892 (2.6) | 3087 (4.0; 3.8 to 4.1) | 12,210 | 1931 (62.6) | |

| Karnataka | 2017 | 12,489,357 | 12,086,328 (96.8) | 110,910/110,910a (100) [0.9] | 4093/110,910 (3.7) | Nil | Nil | 4093 (3.7; 3.6 to 3.8) | 2952 | NA |

| 2018 | NA | 10,265,692 (NA) | 90,041/99,946 (90.1) [0.9] | 1822/85,408 (2.1) | 1914/15,609 (12.3) | 372/1715 (21.7) | 2957 (2.7; 2.6 to 2.8) | 3472 | NA | |

| 2019 | NA | 43,478,614 (NA) | 260,157/307,519 (84.6) [0.6] | 4205/245,243 (1.7) | 4527/42,077 (10.8) | 1836/5747 (40.0) | 7283 (2.8; 2.4 to 2.7) | 5969 | NA | |

| Ladakh (Leh & Kargil) | 2018 | 35,798 | 25,116 (70.2) | 462/NA (NA) [1.8] | 3/374 (0.8) | 0/148 (0) | 13/462 (2.8) | 13 (2.8; 1.7 to 4.8) | 1932 | 13 (100) |

| 2019 | 8996 | 6199 (68.9) | 462/NA (NA); [7.5] | 12/205 (5.9) | Nil | 1/462 (0.2) | 13 (2.8; 1.7 to 4.8) | 477 | 13 (100) | |

| Maharashtra | 2017 | 10,363,469 | 9,413,295 (90.8) | 43,945/55,381 (79.0) [0.5] | 1357/43,945 (3.1) | 2336/17,663 (15.9) | 225/1698 (13.2) | 2654 (6.0; 5.8 to 6.3) | 3547 | 2410 (90.8) |

| 2018 | 23,479,803 | 21,281,430 (90.6) | 74,634/91,225 (81.5) [0.4] | 1925/74,634 (2.6) | 4078/25,283 (16.1) | 411/5209 (7.9) | 3912 (5.2; 5.1 to 5.4) | 5440 | 3845 (98.3) | |

| 2019 | 95,163,760 | 87,568,441 (92.0) | 192,300/211,850 (90.8) [0.2] | 5815/192,300 (3.0) | 27,009/145,805 (18.5) | 1350/23,570 (5.7) | 11,363 (5.9; 5.8 to 6.0) | 7707 | 11,151 (98.1) | |

| Manipur | 2017 | 46,429 | 31,291 (67.4) | 1827/NA (NA) [5.8] | 37/1827 (2.0) | 0/5 (0) | Nil | 37 (2.0; 1.5 to 2.8) | 846 | NA |

| Mizoram | 2017 | 16,8028 | 86,391 (51.4) | 2378/NA (NA) [2.8] | 14/272 (5.2) | 0/5 (0) | 47/2106 (2.2) | 61 (2.6; 2.0 to 3.9) | 1416 | 61 (100) |

| Tamil Nadu | 2017 to 2019 | 8,781,657 | 4,967,754 (56.6) | 1,972,878/ 3,343,099 (59.0) [39.7] | NA/1,972,878 (NA) | NA/1,136,568 (NA) | 2019 data: 277/5969 (4.6) | 6580 (0.3; 0.3 to 0.4) | 755 | 2017 data: 2468/3304 (74.7) |

| Uttarakhand | 2017 to 2019 | 1,412,700 | 125,516 (8.9) | 10,716/NA (NA) [8.5] | 324/10,716 (3.0) | 68/432 (15.7) | 15/600 (2.5) | 407 (3.8; 3.5 to 4.2) | 308 | NA |

| Years | Target Population Mapped | Numbers Screened from Population Mapped (%) | TB Tested in Those with Presumptive TB (%) and among Those Screened [%] | TB Diagnostic Tests | TB Diagnosed (%; 95% CI) | NNS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partner Agency | Sputum Positive (%) | X-ray Abnormal (%) | CBNAAT Positive (%) | Anti-TB Treatment Initiated (%) | ||||||

| The Union Axshya Project | 2013-2015 | NA | 8,120,015 households (NA) | 225,443/541,406 (41.6) [NA] | 21,268/225,443 (9.4) | Nil | Nil | 21,268 (9.4; 9.3 to 9.6) | NA | 20,589 (96.8) |

| (The Global Fund) | 2015-2017 | NA | 9,003,299 households (NA) | 272,836/535,613 (50.9) [NA] | 25,493/272,836 (9.3) | Nil | Nil | 25,493 (9.3; 9.2 to 9.5) | NA | 24,524 (96.2) |

| 2018-2020 | NA | 25,575,009 (NA) | 216,075/292,557 (73.9) [0.9] | 15,550/216,075 (7.2) | 4190/10,136 (41.3) | 784/2166 (36.0) | 21,012 (9.7; 9.6 to 9.9) | 1217 | 18,373 (87.4) | |

| ICMR TIE-TB (The Global Fund) | 2015-2017 | 6,117,597 | 55,707 (0.91) | 49,998/49,998 (100) [89.7] | 2091/49,998 (4.2) | 5,272/45,840 (11.5) | NA | 4286 (8.5; 8.3–8.8) | 13 | 4286 (100) |

| KHPT Project THALI (USAID) | 2017-2019 | NA | NA | 21,171/28,473 (74.3) [NA] | 1578/NA | NA | 30/NA | 2247 (10.6; 10.2 to 11.0) | NA | 2174 (96.8) |

| World Health Partners (USAID) | 2017–2019 | 1,707,990 | 381,761 (22.3%) | 6254/6254 (100) [1.6] | 451/6254 (7.2) | Nil | Nil | 451 (7.2; 6.6 to 7.9) | 847 | 451 (100) |

| 2018-2020 | NA | 18,705 (NA) | 1155/1398 (82.6) [6.1] | 46/279 (16.5) | 156/1155 (13.5) | 13/192 (6.8) | 215 (18.6; 16.5 to 21.0) | 87 | 215 (100) | |

| 2019 | NA | 20,863 (NA) | 501/501 (100) [2.4] | 34/501 (6.8) | Nil | Nil | 34 (6.8; 4.9 to 9.3) | 614 | 34 (100) | |

| 2018-2019 | NA | 1389 (NA) | 19/42 (45.2) [1.3] | 1/19 (5.3) | Nil | Nil | 1 (5.3; 0.9 to 24.6) | 1389 | 1 (100) | |

| World Vision (The Global Fund) | 2015-2017 | 3,535,072 | 1.8 million households (NA) | 71,980/NA (NA) [NA] | NA | NA/71,980 | NA | 34,761 (48.4; 48.0 to 48.7) | NA | 34,761 (100) |

| State/Union Territory (Estimated Population in Millions) | Vulnerable Target Population Mapped from State Population (%) | Numbers Screened from Mapped Target Population (%) | Numbers with Presumptive TB Tested from Those Screened (%) | TB Diagnosed in Those Tested (%; 95% CI) | Number Needed to Screen (NNS) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Uttar Pradesh (223.43) | 44,019,832 (18.9) | 43,255,104 (98.3) | 156,980 (0.4) | 10,121 (6.5; 6.3 to 6.6) | 4274 |

| 2 | Maharashtra (125.74) | 85,791,971 (68.2) | 333,161 (0.4) | 311,650 (93.5) | 12,823 (4.1; 4.0 to 4.2) | 26 |

| 3 | Bihar (124.76) | 884,094 (0.7) | 13,776 (1.6) | 49 (0.4) | 7 (1.3; 7.1 to 26.7) | 1968 |

| 4 | West Bengal (99.91) | 13,608,540 (13.6) | 11,997,372 (88.2) | 232,599 (1.9) | 1810 (0.8; 0.7 to 0.8) | 6628 |

| 5 | Madhya Pradesh (84.36) | 14,668,164 (17.4) | 1,070,951 (7.3) | 44,341 (4.1) | 4912 (11.1; 10.8 to 11.4) | 218 |

| 6 | Tamil Nadu (81.4) | 1,148,451 (1.4) | 281,122 (24.5) | 14,744 (5.2) | 395 (2.7; 2.4 to 3.0) | 711 |

| 7 | Rajasthan (79.92) | 8,090,518 (10.1) | 6,906,255 (85.4) | 43,083 (0.6) | 1067 (2.5; 2.3 to 2.6) | 6473 |

| 8 | Gujarat (69.76) | 65,882,010 (94.4) | 50,847,334 (77.2) | 121,466 (0.2) | 4565 (3.8; 3.7 to 3.9) | 11,138 |

| 9 | Karnataka (68.51) | 15,507,273 (22.6) | 92,436 (0.6%) | 87,505 (94.7) | 2939 (3.4; 3.3 to 3.5) | 31 |

| 10 | Andhra Pradesh (52.54) | 1,335,818 (2.5) | 1,151,885 (86.2) | 51,982 (4.5) | 1685 (3.2; 3.1 to 3.4) | 683 |

| 11 | Odisha (46.32) | 45,292,673 (97.8) | 41,965,511 (92.7) | 222,198 (0.5) | 5116 (2.3; 2.2 to 2.4) | 8202 |

| 12 | Jharkhand (39.48) | 14,854,650 (37.6) | 15,230 (0.1) | 10,731 (70.5) | 1891 (17.6; 16.9 to 18.4) | 8 |

| 13 | Telangana (37.92) | 754,912 (2.0) | 60,632 (8.0) | 4822 (8.0) | 1207 (25.0; 23.8 to 26.3) | 50 |

| 14 | Assam (35.05) | 79,329 (0.2) | 15,243 (19.2) | 2029 (13.3) | 91 (4.5; 3.7 to 5.5) | 167 |

| 15 | Kerala (35.44) | 1,171,034 (3.4) | 37,685 (3.2) | 29,166 (77.4) | 802 (2.8; 2.6 to 2.9) | 47 |

| 16 | Punjab (30.67) | 4,856,533 (15.8) | 4,317,208 (88.9) | 5371 (0.1) | 529 (9.9; 9.1 to 10.7) | 8161 |

| 17 | Chhattisgarh (30.03) | 571,344 (1.9) | 7462 (1.3) | 6436 (86.3) | 170 (2.6; 2.3 to 3.1) | 44 |

| 18 | Haryana (29.44) | 9,889,536 (33.6) | 8,282,557 (83.8) | 30,539 (0.4) | 866 (2.8; 2.7 to 3.0) | 9564 |

| UT1 | Delhi (19.05) | 1716 (0.0) | 985 (57.4) | 256 (26.0) | 30 (11.7; 8.3 to 16.2) | 33 |

| UT2 | Jammu & Kashmir (14.50) | 422,954 (2.9) | 141,814 (33.5) | 15,254 (10.8) | 190 (1.3; 1.1 to 2.4) | 746 |

| 19 | Uttarakhand (11.63) | 1,291,237 (11.1) | 1,785,11 (13.8) | 2953 (1.7) | 100 (3.4; 2.8 to 4.1) | 1785 |

| 20 | Himachal Pradesh (7.5) | 7,485,901 (99.8) | 22,709 (0.3) | 15,852 (69.8) | 595 (3.8: 3.5 to 4.1) | 38 |

| 21 | Tripura (3.96) | 198,624 (5.0) | 98,845 (49.8) | 9084 (9.2) | 109 (1.2; 1.0 to 1.5) | 906 |

| 22 | Meghalaya (3.66) | 1,435,077 (39.2) | 532,359 (37.1) | 1064 (0.2) | 28 (2.6; 1.8 to 3.8) | 19,012 |

| 23 | Manipur (3.12) | 53,336 (1.7) | 32,289 (60.5) | 3802 (11.8) | 52 (1.4; 1.0 to 1.8) | 621 |

| 24 | Nagaland (2.07) | 91,005 (4.4) | 23,272 (25.6) | 1291 (5.5) | 23 (1.8; 1.2 to 2.7) | 1011 |

| 25 | Arunachal Pradesh (1.64) | 56,236 (3.4) | 48,925 (87.0) | 2350 (4.8) | 73 (3.1; 2.5 to 3.9) | 670 |

| 26 | Goa (1.54) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| UT3 | Puducherry (1.50) | 16,152 (1.1) | 10,886 (67.4) | 109 (1.0) | 5 (4.6; 2.0 to 10.1) | 2177 |

| 27 | Mizoram (1.26) | 1,35,399 (10.7) | 59,883 (44.2) | 293 (0.5) | 8 (2.7; 1.4 to 5.3) | 7485 |

| UT4 | Chandigarh (1.17) | 145,297 (12.4) | 6962 (4.8) | 703 (10.1) | 36 (5.1; 3,7 to 7.0) | 193 |

| UT5 | Dadra & Nagar Haveli; Daman & Diu (0.80) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 28 | Sikkim (0.66) | 62,853 (9.6) | 11,034 (17.6) | 149 (1.4) | 4 (2.7; 1.1 to 6.7) | 2759 |

| UT6 | Andaman & Nicobar (0.39) | 389,615 (99.0) | 44,762 (11.5) | 432 (1.0) | 21 (4.9; 3.2 to 7.3) | 2130 |

| UT7 | Ladakh (0.34) | 5952 (1.7) | 5952 (100) | 14 (0.2) | 0 (0) | NA |

| UT8 | Lakshadweep (0.07) | 70,070 (100) | 70,070 (100) | 509 (0.7) | 3 (0.6; 0.2 to 1.7) | 23,356 |

| India (1,377.54) | 340,268,106 (24.7) | 171,940,182 (50.5) | 1,429,806 (0.8) | 52,273 (3.66; 3.63 to 3.69) | Median: 906 (IQR 108 to 6550) |

| Category | Challenges | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Health system challenges leading to pre-diagnostic drop-outs and poor documentation of ACF referrals, TB notifications, treatment outcomes and impact of ACF | Poor access to health facilities | Failure to get tested at health facilities due to the distance and time taken to travel, difficulties in finding transport at convenient times, loss of wages incurred due to travel times. |

| Non-availability of all diagnostic tests at peripheral health institutions | Chest radiography and GeneXpert are often not available at one place, but at different levels of health care provision (secondary and tertiary hospitals). This makes it difficult for people to complete the required tests in a day. | |

| Difficulties in accessing radiography services at secondary hospitals | ACF patients are not considered a priority compared to emergency referrals; shortages in materials, resources and equipment malfunction also contribute. | |

| Poor documentation of ACF referrals for diagnostic tests Lack of a separate ACF module in the data management system | Referral slips given by field staff for diagnostic tests are often misplaced by patients or are not entered in diagnostic facilities as an ACF referral. Nikshay, the online data management tool, does not specifically link TB notifications identified by the ACF programme with treatment outcomes. | |

| Healthcare provision challenges leading to poor ACF screening and diagnostic outcomes | Poor TB awareness among general population | Despite time and effort spent on advocacy, communication and social mobilisation, large segments of the vulnerable population are unaware of the importance of the ACF programme and were unwilling to fully comply with ACF requirements. |

| Obtaining an exact denominator of the population, and the geographical boundaries of areas to be mapped | Difficulty in accurately estimating the number of people residing in geographical areas that are mapped. Figures from the previous census are not dynamic and do not accurately reflect the actual population numbers, or its composition, at the time of ACF activities. In many areas, the geographical boundaries of the areas mapped are not clearly demarcated and often overlapped with adjacent areas. | |

| Difficulties due to mountainous terrains and hard-to access areas | Areas in the country with mountainous terrains (as in Leh and Kargil in Ladakh), or other hard-to-reach areas, make it difficult for ACF teams to screen all of the mapped populations. | |

| Challenges faced by patients and families leading to poor compliance with ACF requirements | Pressure to undergo screening and testing | People identified with presumptive TB often do not feel unwell. Requests to visit designated diagnostic centres are perceived as undue pressure from the health workers, particularly if they are busy and if the travel involves long distances and time away from productive work |

| Non-availability of all family members during screening visits | Not all family members can be present when health workers made home-visits. Available family members may find it difficult to accurately report symptoms in other family members. | |

| Non-availability of investigations | Patients are dissatisfied when tests are unavailable when they visit diagnostic facilities, and they have to make multiple visits to complete their tests. | |

| Out-of-pocket expenditure for diagnostic tests | Diagnostic tests are provided free of cost at government-designated facilities. Testing at private diagnostic facilities is often more convenient, but the expenditure involved is considerably greater. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burugina Nagaraja, S.; Thekkur, P.; Satyanarayana, S.; Tharyan, P.; Sagili, K.D.; Tonsing, J.; Rao, R.; Sachdeva, K.S. Active Case Finding for Tuberculosis in India: A Syntheses of Activities and Outcomes Reported by the National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed6040206

Burugina Nagaraja S, Thekkur P, Satyanarayana S, Tharyan P, Sagili KD, Tonsing J, Rao R, Sachdeva KS. Active Case Finding for Tuberculosis in India: A Syntheses of Activities and Outcomes Reported by the National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2021; 6(4):206. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed6040206

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurugina Nagaraja, Sharath, Pruthu Thekkur, Srinath Satyanarayana, Prathap Tharyan, Karuna D. Sagili, Jamhoih Tonsing, Raghuram Rao, and Kuldeep Singh Sachdeva. 2021. "Active Case Finding for Tuberculosis in India: A Syntheses of Activities and Outcomes Reported by the National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 6, no. 4: 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed6040206

APA StyleBurugina Nagaraja, S., Thekkur, P., Satyanarayana, S., Tharyan, P., Sagili, K. D., Tonsing, J., Rao, R., & Sachdeva, K. S. (2021). Active Case Finding for Tuberculosis in India: A Syntheses of Activities and Outcomes Reported by the National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 6(4), 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed6040206