e-Diagnosis in Medical Parasitology

Abstract

1. Why e-Diagnosis?

- Less importance/attention is given to parasitic diseases in humans in the developed world (including Australia).

- The re-distribution of parasites due to human/animal movement and environmental and practice changes has brought parasites into the developed world.

- There are declining numbers of experts in this field, especially morphologists.

- The internet ‘savvy’ public who ‘self-diagnose’ want to ‘confirm’ their thoughts.

2. Who Is the Team?

3. What Kind of Material/Advice is Sought?

- Images for identification (macroscopic and microscopic)

- Histology sections of tissues with possible parasites

- Molecular identification/availability

- Interpretation/availability of serology for parasites

- Advice on testing to exclude parasites

- Management of parasitic infections (treatment and follow-up)—OzBug (Australian email group of interested clinical experts)

- Advice on/to “internet-savvy” patient concerns

4. Type of Parasites Received from Intestine, Tissues or Blood

- Protozoa

- Nematodes

- Trematodes

- Cestodes

- Arthropods

- Pseudo-parasites and artefacts

5. Cases

5.1. Case 1: Lump in the Back (Melbourne, VIC, Australia)

5.2. Case 2: Lump in the Axilla (Brisbane, QLD, Australia)

5.3. Case 3: Larvae, Adults and Eggs in CSF/Brain (Adelaide, SA, Australia)

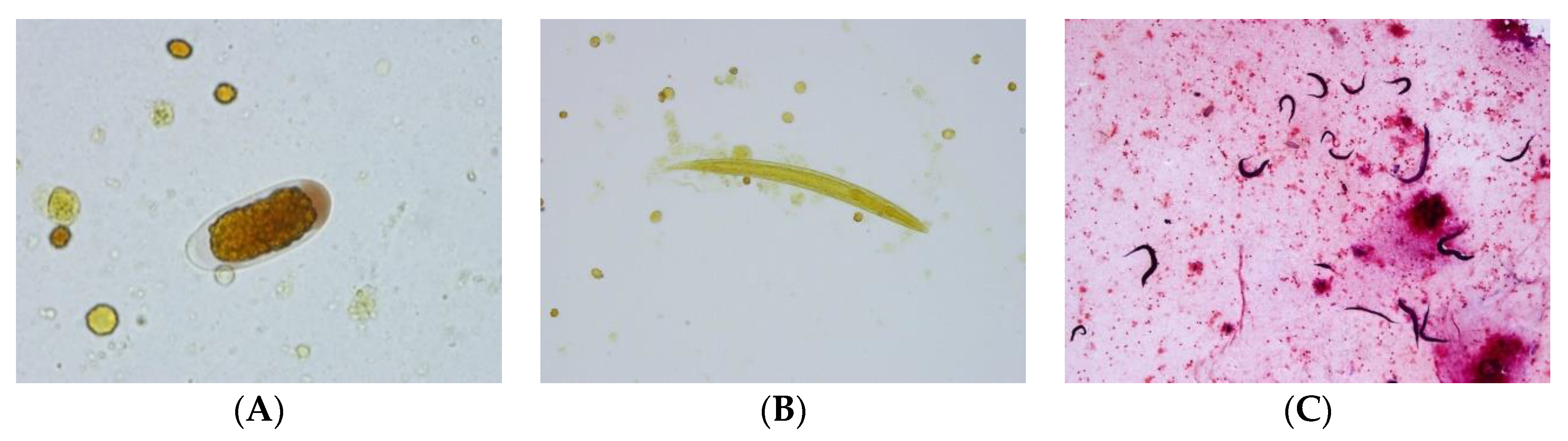

- The structure of the esophagus and ratio to gut may also help us. The two illustrated larvae could just be rhabditiform and hence no notching of tail; there does seem to be a darker region near the genital primordium zone in one photo, but we also lack ability to gain more definition of these key points. (Norbert Ryan).

- The egg looks very much like a Trichostrongylus egg (but the size of the eggs is too small), and the larvae have features that are reminiscent of that species also, particularly the wavy pattern of the intestine (John Walker).

- First of all, very few documented cases (of Strongyloides) in the brain/CSF. Have no explanation for eggs/rhabditiform larvae in this site (Lynne Garcia).

- I don’t think it is the usual suspects, namely Strongyloides or Angiostyrongylus, on morphological grounds. Eggs are not normally seen in angiostrongyliasis. They look most like stages of Trichostrongylus, but that infection does not disseminate, or at least there are no reports thereof. Thus, I think this is a very unusual aberrant infection with Trichostrongylus or similar nematode that is not normally found in humans (John Frean).

- I found a lovely description of all stages of Halicephalobus gingivalis in Anderson et al. (1998). This is now regarded as the correct name for the parasite. The drawings are very consistent with what is in the images. Note the elongated eggs, the recurved ovaries, and of course the rhabditoid esophagus (Rick Speare).

- Please don’t waste the nematodes you have by rushing in and using them immediately for PCR. They should be morphologically described first; then do PCR. Additionally, some should be kept in case it is a new species. Don’t forget the light microscopy and measurements, as well as SEM. Of course, the latter looks more spectacular but usually carries less taxonomic weight (Rick Speare).

- The sequence results have come back, and the worms are positive for Halicephalobus gingivalis. The 28s D2/D3 primers from Nadler’s 2003 paper were used and got the sequence found below (2). This sample was 99% identical to GenBank accession AY294177 over 786 base pairs (Anson Kohler).

- The combination of case details, plus description of the nematodes, plus PCR gives the maximum value. Fabulous effort! Good example of the value of a collaborative dispersed group in diagnosing unusual parasites! (Rick Speare)

5.4. Case 4: Worm Passed in Feces (Wollongong, NSW, Australia)

6. Limitations of This Diagnostic Procedure

- Poor images may be sent:

- -

- Not enough images: multiple images at different magnification levels and that cover key parts of the parasite are not always sent.

- -

- Poor quality photos that are out of focus or focused on wrong part may be sent. The new smart phones take very good images, so this should not be an excuse.

- No relevant history: Age, epidemiology, travel, exotic food, contact with animals, medication, immune status are all important, and, quite often, this is not communicated.

- Arthropods or large worms received in formalin and sectioned: Arthropods and large worms are better photographed whole and not sectioned. When stored in 70% alcohol, formalin makes specimens ‘brittle.’

- ‘Degenerate’ or dying parasite (histology-section): Morphology may not be typical enough to make a diagnosis.

- Not enough follow up material: The specimen or multiple images should be held onto if required for further identification.

- Direct contact with non-scientific public (via social media and internet):

- -

- Abuse: Some members of the public do not like answers that they do not want to hear and can get abusive.

- -

- Legal aspects: Advice/opinions given over limited information and presented this way should be taken in the context of clinical pictures. It should be made clear that this is an opinion, and a clinical judgment should be made by the treating doctor. Advice on treatment (drugs) should be avoided over internet/social media, as other medical history information needs to be taken in consideration. Wrong interpretation/understanding can lead to legal ramifications.

7. Summary and the Future

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crowe, A.; Koehler, A.V.; Sheorey, H.; Tolpinrud, A.; Gasser, R.B. PCR-coupled sequencing achieves specific diagnosis of onchocerciasis in a challenging clinical case, to underpin effective treatment and clinical management. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018, 66, 192–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.K.; Crawford, A.; Moore, C.V.; Gasser, R.B.; Nelson, R.; Koehler, A.V.; Bradbury, R.S.; Speare, R.; Dhatrak, D.; Weldhagen, G.F. First human case of fatal Halicephalobus gingivalis meningoencephalitis in Australia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 1768–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKelvie, P.; Reardon, K.; Bond, K.; Spratt, D.M.; Gangell, A.; Zochling, J.; Daffy, J. A further patient with parasitic myositis due to Haycocknema perplexum, a rare entity. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 20, 1019–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koehler, A.V.; Spratt, D.M.; Norton, R.; Warren, S.; Mcewan, B.; Urkude, R.; Murth, S.; Robertson, T.; Mccallum, N.; Parsonson, F.; et al. More parasitic myositis cases in humans in Australia, and the definition of genetic markers for the causative agents as a basis for molecular diagnosis. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016, 44, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sheorey, H. e-Diagnosis in Medical Parasitology. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed5010008

Sheorey H. e-Diagnosis in Medical Parasitology. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2020; 5(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed5010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleSheorey, Harsha. 2020. "e-Diagnosis in Medical Parasitology" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 5, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed5010008

APA StyleSheorey, H. (2020). e-Diagnosis in Medical Parasitology. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 5(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed5010008