Community Participatory Approach to Design, Test, and Implement Interventions That Reduce Risk of Bat-Borne Disease Spillover: A Case Study from Cambodia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

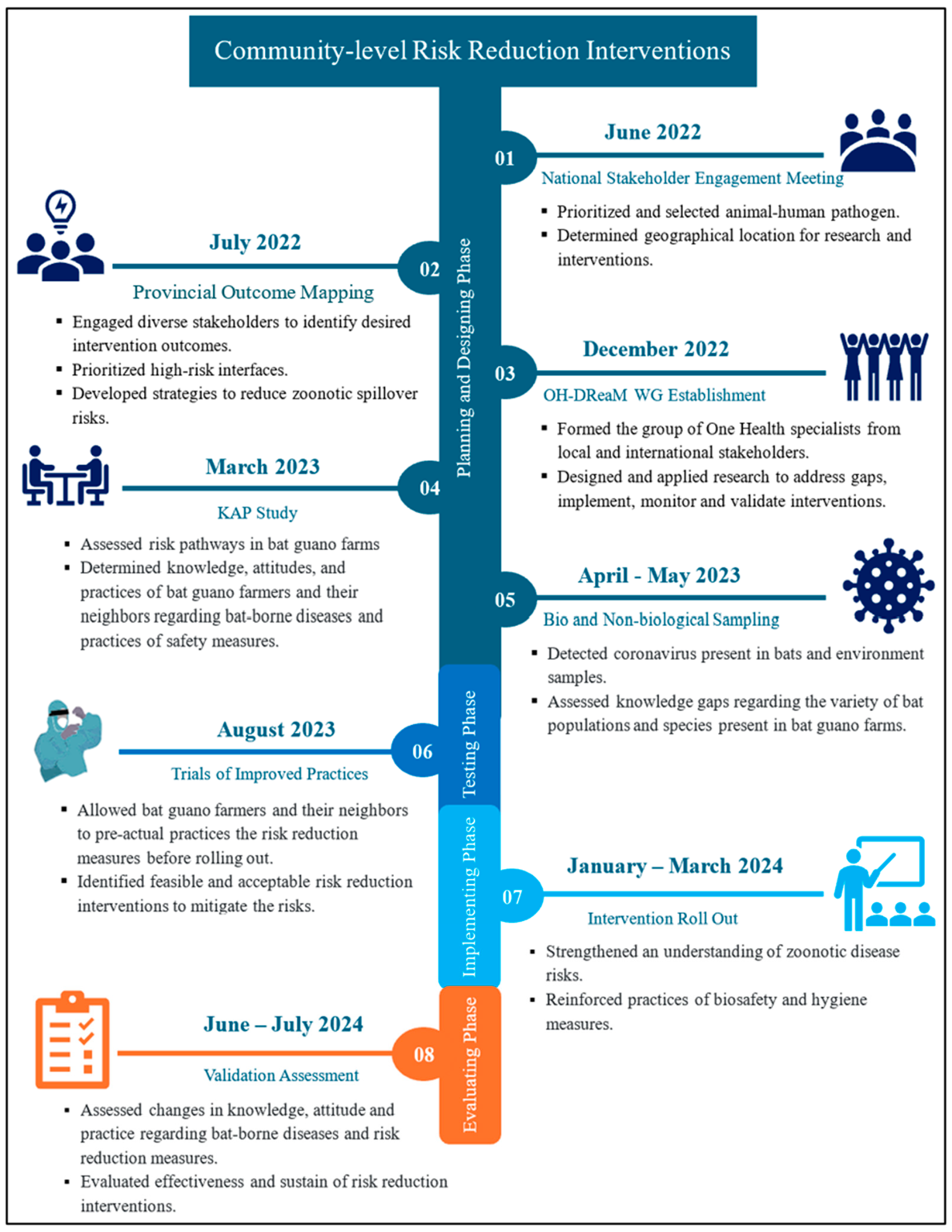

2.1. Planning and Design Phase

2.1.1. Outcome Mapping: National Stakeholder Engagement Meeting

2.1.2. Provincial Outcome Mapping

2.1.3. One Health Design, Research, and Mentorship Working Group Establishment

- Research and Knowledge Gap Assessment: Collaborative research to identify knowledge, attitude, and practice gaps among bat guano farmers and their neighbors.

- Intervention Design and Validation: Participatory designing, testing, and prioritizing feasible risk reduction interventions through discussions with community members.

- Implementation of Risk Reduction Interventions: Collaborative implementation of educational activities, household visits, and technical support to promote biosafety and hygiene practices.

- Monitoring and Evaluation: Joint monitoring and evaluation of intervention effectiveness and making necessary adjustments to strengthen risk reduction efforts.

2.2. Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Study

2.3. Sampling

2.4. Intervention Testing Phase

Trials of Improved Practices

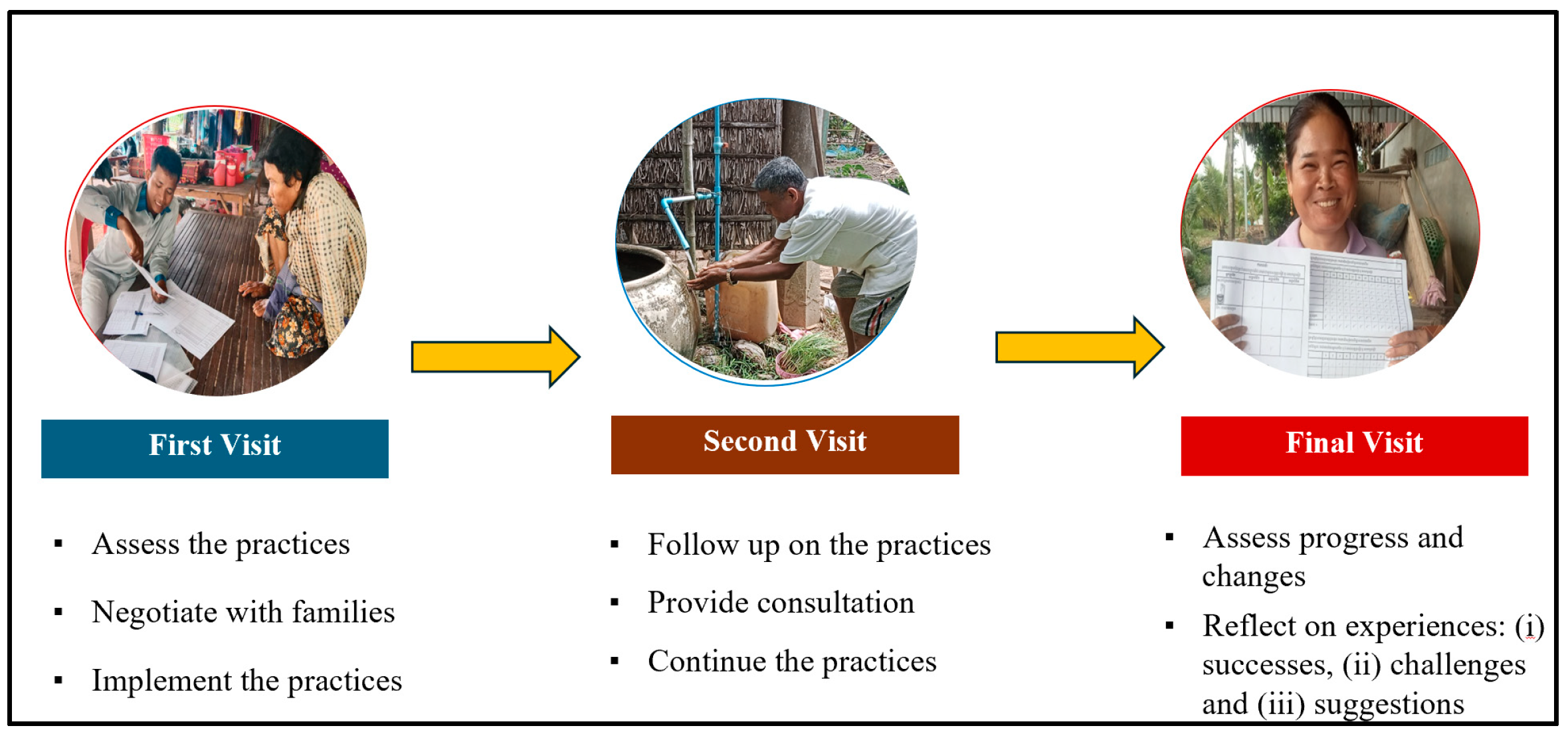

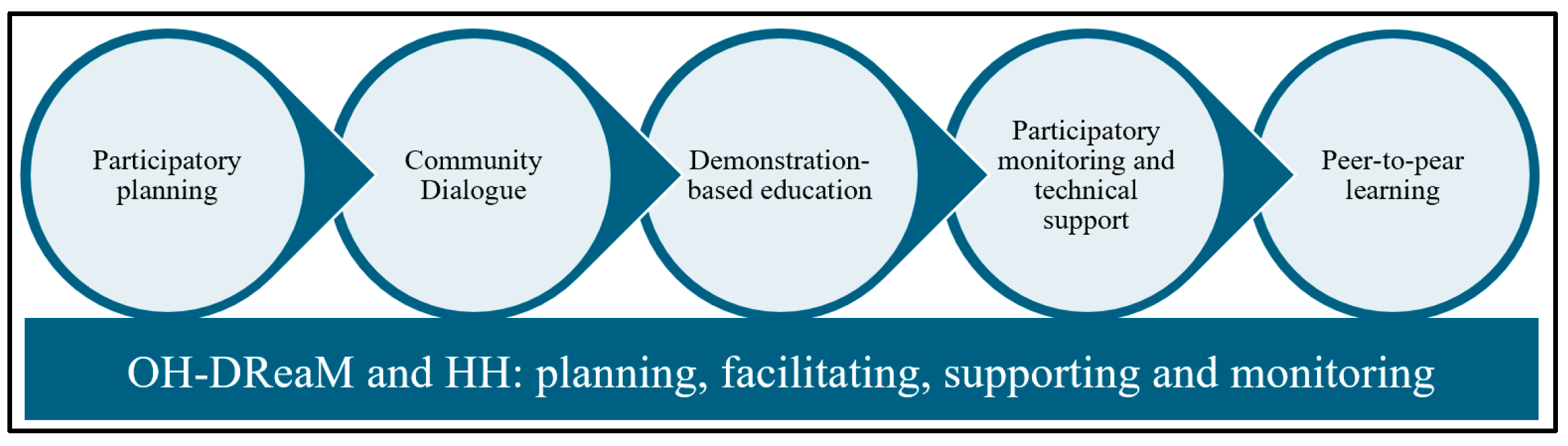

2.5. Implementation Phase

Intervention Roll-Out

2.6. Evaluation Phase

Validation Assessment

2.7. Ethical Statement

3. Results

3.1. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Study (KAP)

“I don’t think it has an infection either. If it had been infected, I would have died quite a long time ago. But I think the government and foreigners are worried.” (IDI, M, bat guano farmer, 68 years old).

In fact, we have used Krama or caps for a long time when we enter the bat farm so that we can protect ourselves from becoming dirty with bat waste. (FGD, F, bat guano farmer)

“Before they didn’t use anything. Only a scarf or cap to cover the head. The cap is used to protect us from urine because of smell or drops of urine or guano from the bats, but I don’t think they protect us from disease or virus.” (IDI, M, CC, 67 years old)

“They [bat and non-bat guano producers] live together as usual, they understand each other. Some people complain about the noise and smell. I think they could not talk with bat guano producers directly, as they are afraid that those people will be angry. People murmur about this. I never received complaints officially from non-bat guano farmers and not all non-bat guano producers complain. For example, among 5 non-bat households, there might be 1 that complains. I think the rest are getting used to the smell.” (IDI, F, CCWC, 42 years old)

3.2. Sampling

3.3. Risk Reduction Intervention Design and Testing

Trials of Improved Practices

“It’s like a reminder for me not to forget to protect myself”. (BGP_011)

“I will continue using them (PPE) to take care of my health.” (BGP_009)

“I don’t get much guano, so I mostly just collect and dry it and keep it in the open jar. I will put it in the common plastic bag if anyone buys that guano…sometimes the chickens from other HH jumped into that jar to eat insects, sleep and sometimes also lay eggs there…” (BGP_005)

“I will tell my daughters grandchildren to keep good hygiene by cleaning surfaces every morning with soap. We have to live in good hygiene because we are living close to the bat roosts.” (NBGP_011)

3.4. Intervention Validation Assessment

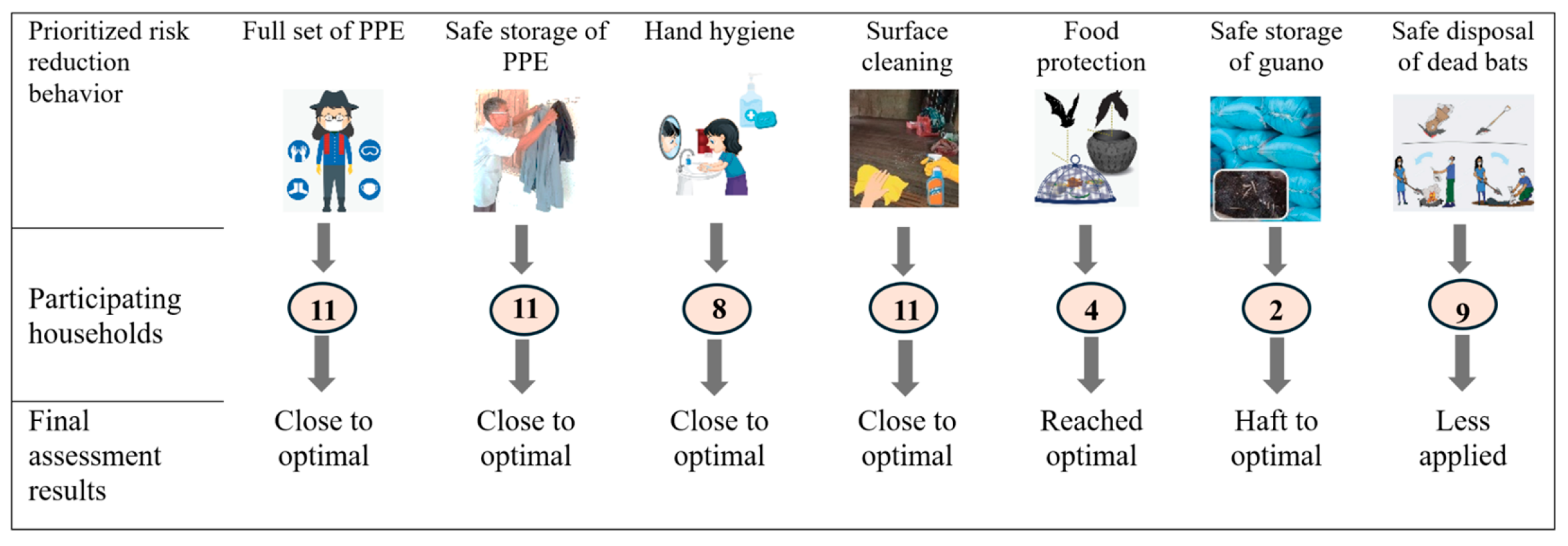

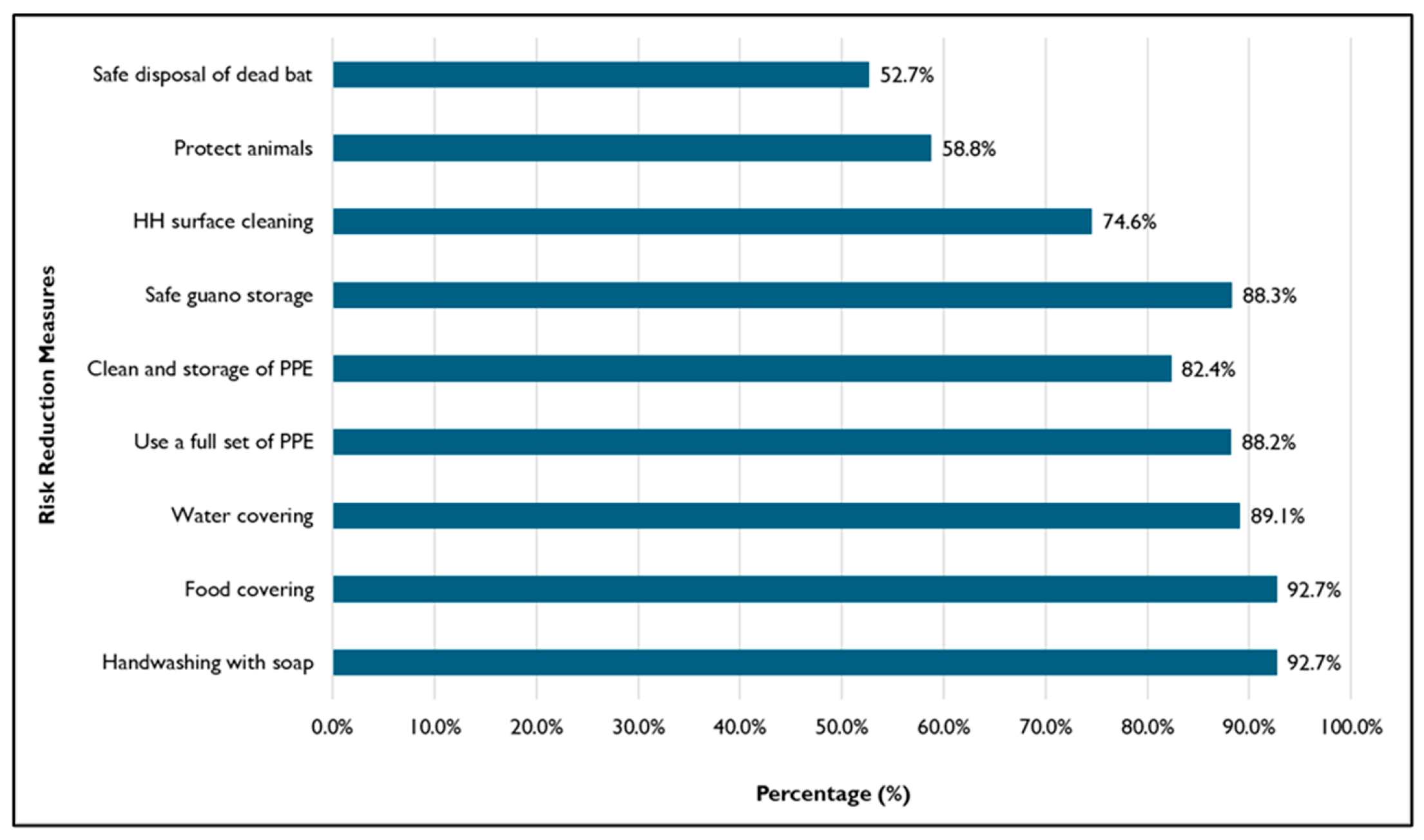

3.4.1. Behavior and Risk Reduction Practices

“Handwashing is the most important because after we work, we need to wash. If we don’t wash, we touch food and eat so it will affect us. In short, whenever we finish the guano collection, we need to shower and wash our hands immediately.” (FGD_BGP_Male)

“Raising the net is good as it is easier than before. It also protects from chickens and dogs as the dog really likes playing in the bat guano and protects them from carrying out the infectious diseases. It also saves time in collecting the guano as well.” (FGD_BGP_Female)

“Last time the bat flew into my water container, so in the morning I took them and buried them. I also throw away that water without giving it to my cow.” (FGD_NBGP)

3.4.2. Risk Reduction Effectiveness

“The use of full PPE may protect about 90% but not 100% as we need to shower with soap. If the disease is serious, it can also protect some, but it is not a serious disease it can protect fully.” (FGD_BGP_Female)

“The project educated us on zoonotic diseases and prevention techniques. We understood and applied it, so we feel confident about 90% that we are safer from the spillover risk. We are confident enough to be working at the farms.” (FGD_BGP_Male)

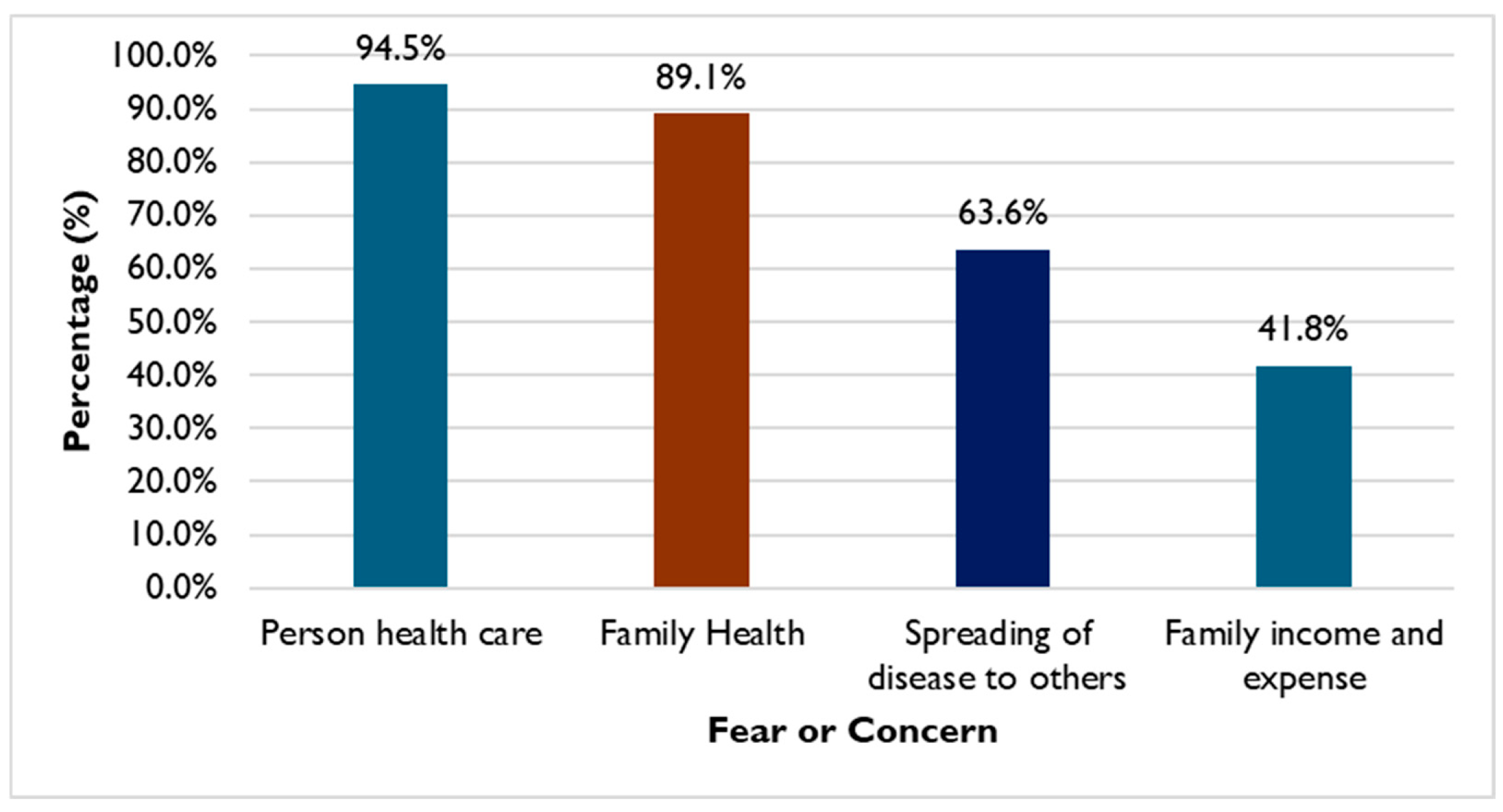

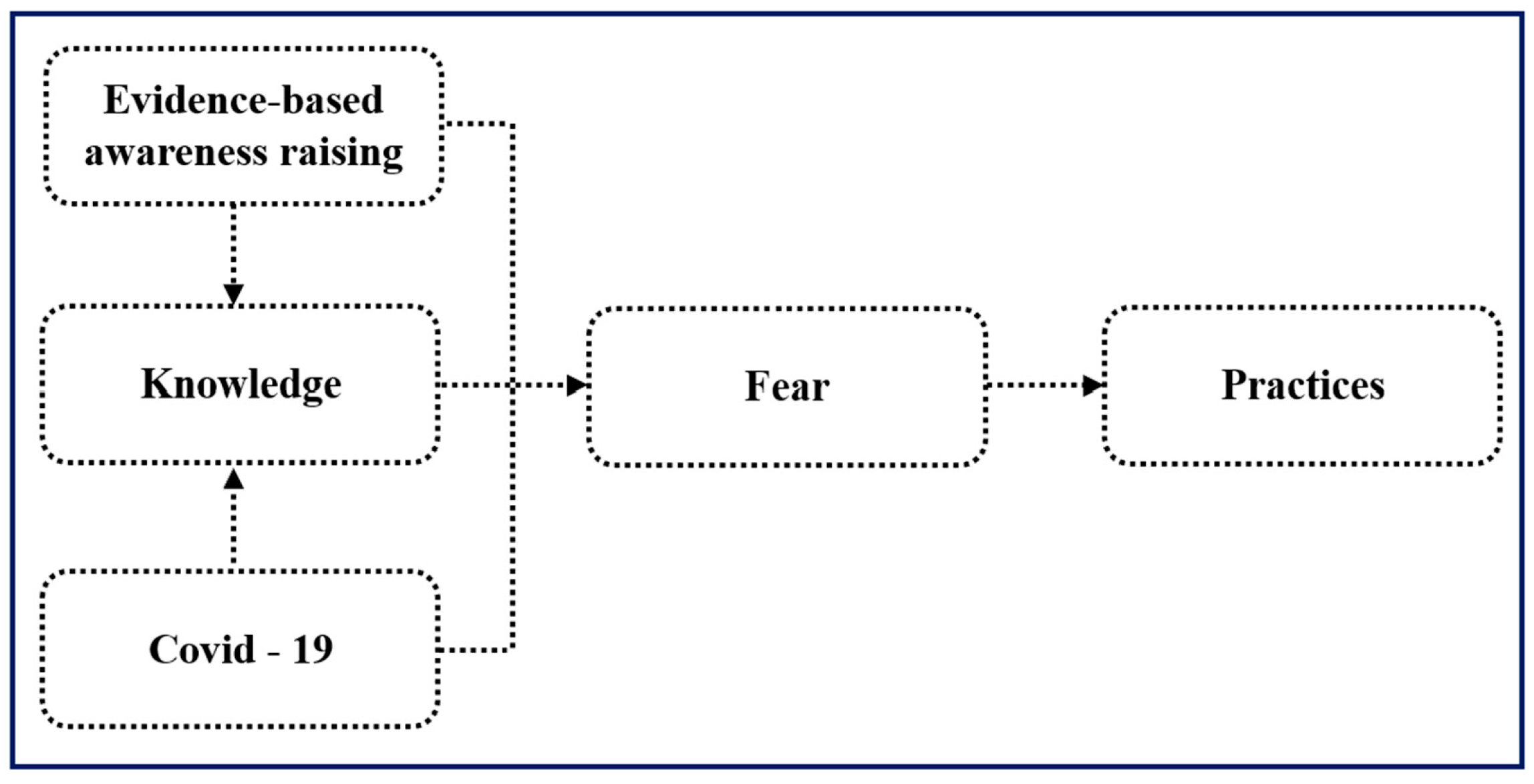

3.5. Behavior Change Motivators

“We are changing because the project tells us. Then why do we change? Because we are afraid of infectious diseases. Especially after we see COVID. We are afraid there will be some diseases like COVID to happen again.” (FGD_BGP_Female)

“COVID is also an example of the disease, and they learn and react to this quickly.” (IDI_PDA)

“We are afraid of viruses from bats for our health and if it affects us and will affect our family and other people in this community.” (FGD_BGP_Female)

“We change because we take care of our health. [Being] sick is never easy. Being sick also costs so much money. Whenever we are sick, it will be gone even with how much money we have (spending on health care). When we are sick we will lose our jobs and money. So just to protect our health is easier…” (FGD_BGP_Male)

3.6. Risk Reduction Sustainability

“We will continue practicing hygiene even when the project phases out because the project taught us. We have knowledge and we will practice because we want to prevent infectious diseases and protect our health. We will be healthy if we can avoid disease and we also can save more money.” (FGD_BGP_Female)

“I plan to make a report and report the results to the commune and local authority to ask them to take over and take care these activities…The most important thing is the support of local authority…For me, I am still committed to come over this area to see how the activities are and continue to raise awareness among them or remind them…I think if we can bring the result to provincial level so that we can ask provincial level to take over…” (IDI_provincial government representative)

“Monks and priests here have knowledge; I also have knowledge so I will continue to share this knowledge and information. Even if I have a new monk coming, I will share with them. I will continue mainstreaming and reminding people through events in the pagoda every full moon day and ceremonies in the village.” (IDI_community representative).

4. Discussion

4.1. Community Participatory Approach

4.2. Understanding Current Practices and Risk Pathways

4.3. Trials of Improved Practices (TIPs)

4.4. Validation Assessment

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| BGP | Bat guano producer |

| CCWC | Commune committee for women and children |

| CD | Commune dialog |

| DBE | Demonstration-based education |

| FGD | Focus group discussion |

| HH | Household |

| IBV | Infectious bronchitis virus |

| IDI | In-depth interview |

| KAP | Knowledge, attitude and practice |

| KII | Key informant interview |

| MAFF | Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries |

| MoE | Ministry of Environment |

| MoH | Ministry of Health |

| NBGP | Non-bat guano producer |

| NGO | Non-governmental organization |

| OH | One Health |

| OH-DReaM | One Health design, research and mentorship |

| OM | Outcome mapping |

| PPE | Personal protective equipment |

| STOP | Strategies to prevent spillover |

| TIP | Trials of Improved Practices |

| WASH | Water, sanitation, and hygiene |

References

- Furey, N. Effect of bat guano on the growth of five economically important plant species. J. Trop. Agric. 2014, 52, 169. [Google Scholar]

- Korn, L.; Ngan, C.; David, R.A.; Srean, P. Bat Guano Application Rate in Horticulture in Cambodia: An Experiment with Tomato. 2023. Available online: https://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/201/300/jrn_agricultural_science/2023/JAS-V15N11-All.pdf#page=28 (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Li, W.; Shi, Z.; Yu, M.; Ren, W.; Smith, C.; Epstein, J.H.; Wang, H.; Crameri, G.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, H.; et al. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science 2005, 310, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijaykrishna, D.; Smith, G.J.D.; Zhang, J.X.; Peiris, J.S.M.; Chen, H.; Guan, Y. Evolutionary insights into the ecology of coronaviruses. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 4012–4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.N. Impacts on Human Health Caused by Zoonoses. Biol. Toxins Bioterrorism 2014, 1, 211–228. [Google Scholar]

- Allocati, N.; Petrucci, A.G.; Di Giovanni, P.; Masulli, M.; Di Ilio, C.; De Laurenzi, V. Bat–man disease transmission: Zoonotic pathogens from wildlife reservoirs to human populations. Cell Death Discov. 2016, 2, 16048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez Francel, L.; García-Herrera, L.; Losada-Prado, S.; Reinoso-Flórez, G.; Sánchez-Hernández, A.; Estrada-Villegas, S.; Lim, B.K.; Guevara, G. Bats and their vital ecosystem services: A global review. Integr. Zool. 2021, 17, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About World Health Organization—Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Zoonotic Disease: Emerging Public Health Threats in the Region. Available online: http://www.emro.who.int/about-who/rc61/zoonotic-diseases.html (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Han, H.J.; Wen, H.L.; Zhou, C.M.; Chen, F.F.; Luo, L.M.; Liu, J.W.; Yu, X.J. Bats as reservoirs of severe emerging infectious diseases. Virus Res. 2015, 205, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, E.T.; Ohemeng, F.; Ayivor, J.; Leach, M.; Waldman, L.; Ntiamoa-Baidu, Y. Understanding framings and perceptions of spillover: Preventing future outbreaks of bat-borne zoonoses. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2017, 26, 396–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Osinubi, M.O.; Osikowicz, L.; McKee, C.; Vora, N.M.; Rizzo, M.R.; Recuenco, S.; Davis, L.; Niezgoda, M.; Ehimiyein, A.M.; et al. Human Exposure to Novel Bartonella Species from Contact with Fruit Bats. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Shi, N.; Shan, F.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, J.; Lu, H.; Ling, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Shi, Y. Emerging 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Pneumonia. Radiology 2020, 295, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, H.; Willcox, A.; Ader, D.; Willcox, E. Attitudes towards and Relationships with Cave-Roosting Bats in Northwest Cambodia. J. Ethnobiol. 2021, 41, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, R.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; López-Baucells, A.; Andriamitandrina, S.F.M.; Andriatafika, Z.E.; Temba, E.M.; Torrent, L.; Burgas, D.; Cabeza, M. Human-Bat Interactions in Rural Southwestern Madagascar through a Biocultural Lens. J. Ethnobiol. 2021, 41, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninsiima, L.R.; Nyakarahuka, L.; Kisaka, S.; Atuheire, C.G.; Mugisha, L.; Odoch, T.; Romano, J.S.; Klein, J.; Mor, S.M.; Kankya, C. Knowledge, perceptions, and exposure to bats in communities living around bat roosts in Bundibugyo district, Uganda: Implications for viral haemorrhagic fever prevention and control. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokop, P.; Fančovičová, J.; Kubiatko, M. Vampires Are Still Alive: Slovakian Students’Attitudes toward Bats. Anthrozoos Multidiscip. J. Interact. People Anim. 2009, 22, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, S.A.; Jamieson, D.J.; Uyeki, T.M. Effects of influenza on pregnant women and infants. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 207, S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, V.; Cappelle, J.; Hul, V.; Hoem, T.; Binot, A.; Bumrungsri, S.; Furey, N.; Ly, S.; Tarantola, A.; Dussart, P. Circulation of Nipah virus at the human-Flying fox interface in Cambodia. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 101, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, P. Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation. Black Gold from Cambodian Bats. 2015. Available online: https://www.merlintuttle.org/cambodian-farmers-friends-of-bats/ (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- USAID. PREDICT Cambodia: One Health in Action (2009–2020); USAID: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, M.H.; Maiman, L.A. Sociobehavioral determinants of compliance with health and medical care recommendations. Med. Care 1975, 13, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dernburg, A.R.; Fabre, J.; Philippe, S.; Sulpice, P.; Calavas, D. A Study of the Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors of French Dairy Farmers Toward the Farm Register. J. Dairy. Sci. 2007, 90, 1767–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herck, K.; Zuckerman, J.; Castelli, F.; Damme, P.; Walker, E.; Steffen, R.; European Travel Health Advisory Board. Travelers’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices on Prevention of Infectious Diseases: Results from a Pilot Study. J. Travel. Med. 2006, 10, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyanju, T.E.; Alarape, A.A.; Musila, S.; Adeyanju, A.T.; Omotoriogun, T.C.; Medina-Jerez, W.; Yellow, U.E.; Prokop, P. Human–Bat Relationships in Southwestern Nigerian Communities. Anthrozoös 2023, 36, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, N.; Shi, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, S.; Ye, M.; Peng, Z.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, H.; Liao, Q.; Huai, Y.; et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) relating to avian influenza in urban and rural areas of China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameh, V.O.; Chirima, G.J.; Quan, M.; Sabeta, C. Public Health Awareness on Bat Rabies among Bat Handlers and Persons Residing near Bat Roosts in Makurdi, Nigeria. Pathogens 2022, 11, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toovey, S.; Jamieson, A.; Holloway, M. Travelers’ Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices on the Prevention of Infectious Diseases: Results from a Study at Johannesburg International Airport. J. Travel Med. 2004, 11, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrian, A.M.; Smith, M.H.; van Rooyen, J.; Martínez-López, B.; Plank, M.N.; Smith, W.A.; Conrad, P.A. A community-based One Health education program for disease risk mitigation at the human-animal interface. One Health 2018, 5, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghai, R.R.; Wallace, R.M.; Kile, J.C.; Shoemaker, T.R.; Vieira, A.R.; Negron, M.E.; Shadomy, S.V.; Sinclair, J.R.; Goryoka, G.W.; Salyer, S.J.; et al. A generalizable one health framework for the control of zoonotic diseases. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad Farhan, N.; Gull, N.; Majeeda, R.; Azhar, R.; Hafiz Muhammad Abrar, A.; Ishrat, P.; Hajirah, R.; Ayesha, R.; Urwa, J.; Zobia, H.; et al. From Awareness to Action Promoting Behavior Change for Zoonotic Disease Prevention Through Public Health Education. 2023. Available online: https://uniquescientificpublishers.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/zon-v1/304-315.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Emiroglu, N.; Khoury, P.; Noble, D. Defining Community Protection: A Core Concept for Strengthening the Global Architecture for Health Emergency Prevention, Preparedness, Response and Resilience. 2024. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/379055/9789240096134-eng.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Moutos, A.; Doxani, C.; Stefanidis, I.; Zintzaras, E.; Rachiotis, G. Knowledge, Attitude and Practices (KAP) of Ruminant Livestock Farmers Related to Zoonotic Diseases in Elassona Municipality, Greece. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2022, 12, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemma, M.; Kinati, W.; Annet, M.; Mesfin, M.; Barbara, W. Community Conversations: A Community-Based Approach to Transform Gender Relations and Reduce Zoonotic Disease Risks. 2019. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/a3c7024f-c37b-41e0-9b9a-f4c06ce2d1b8/content (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Medley, A.M.; Gasanani, J.; Nyolimati, C.A.; McIntyre, E.; Ward, S.; Okuyo, B.; Kabiito, D.; Bender, C.; Jafari, Z.; LaMorde, M.; et al. Preventing the cross-border spread of zoonotic diseases: Multisectoral community engagement to characterize animal mobility—Uganda, 2020. Zoonoses Public Health 2021, 68, 747–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafique, S.; Bhattacharyya, D.S.; Nowrin, I.; Sultana, F.; Islam, R.; Dutta, G.K.; del Barrio, M.O.; Reidpath, D.D. Effective community-based interventions to prevent and control infectious diseases in urban informal settlements in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, S.; Carde, F.; Smutylo, T. Outcome Mapping: Building Learning and Reflection into Development Programs; IDRC—International Development Research Centre: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2001. Available online: https://idrc-crdi.ca/en/book/outcome-mapping-building-learning-and-reflection-development-programs (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- JSI. Trials of Improved Practices Brief. Available online: https://publications.jsi.com/JSIInternet/Inc/Common/_download_pub.cfm?id=26246&lid=3 (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Krieger, L.; Pantaleón, N.; Abreu, D. Trials of Improved Practices (Tips) in the Dominican Republic to Develop a Solid Waste Management System and Social and Behavior Change. Pract. Anthropol. 2023, 45, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.A.; Schnefke, C.H.; Flax, V.L.; Nyirampeta, S.; Stobaugh, H.; Routte, J.; Musanabaganwa, C.; Ndayisaba, G.; Sayinzoga, F.; Muth, M.K. Using Trials of Improved Practices to identify practices to address the double burden of malnutrition among Rwandan children. Public. Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 3175–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fisher, R.A. The Logic of Inductive Inference. R. Stat. Soc. 1935, 98, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, P.-L.; Firth, C.; Street, C.; Henriquez, J.A.; Petrosov, A.; Tashmukhamedova, A.; Hutchison, S.K.; Egholm, M.; Osinubi, M.O.V.; Niezgoda, M.; et al. Identification of a Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-Like Virus in a Leaf-Nosed Bat in Nigeria. mBio 2010, 1, e00208–e00210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, M.V.T.; Ngo Tri, T.; Hong Anh, P.; Baker, S.; Kellam, P.; Cotten, M. Identification and characterization of Coronaviridae genomes from Vietnamese bats and rats based on conserved protein domains. Virus Evol. 2018, 4, vey035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loparimoi, P.M.; Ng’eno, W.K. Effect of Community Participation on Sustainability of Donor Funded Projects in Chukudum, Budi County. J. Public. Policy Gov. 2023, 3, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirigha, E.R. Influence of Community Participation on Sustainability of Donor Funded Projects: Case of Kenya Coastal Development Project Kilifi County, Kenya; University of Nairobi: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chomel, B.B.; Stuckey, M.J.; Boulouis, H.J.; Setién, A.A. Bat-related zoonoses. In Zoonoses: Infections Affecting Humans and Animals; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 697–714. [Google Scholar]

- Baudel, H.; De Nys, H.; Mpoudi Ngole, E.; Peeters, M.; Desclaux, A. Understanding Ebola virus and other zoonotic transmission risks through human–bat contacts: Exploratory study on knowledge, attitudes and practices in Southern Cameroon. Zoonoses Public. Health 2019, 66, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadana, S.; Valitutto, M.T.; Aung, O.; Hayek, L.A.C.; Yu, J.H.; Myat, T.W.; Lin, H.; Htun, M.M.; Thu, H.M.; Hagan, E.; et al. Assessing Behavioral Risk Factors Driving Zoonotic Spillover Among High-risk Populations in Myanmar. EcoHealth 2023, 20, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| (1) | Conduct research on bat ecology and pathogens prevalence to address knowledge gaps in bat guano farming communities; |

| (2) | Conduct a comprehensive national risk assessment to identify and map high-risk bat–human interfaces beyond guano harvesting; |

| (3) | Implement community-level risk reduction interventions to improve biosafety and hygiene practices among bat guano farmers and communities; and |

| (4) | Facilitate the coordination and capacity building of sentinel surveillance teams to monitor for spillover of coronaviruses and other bat-transmitted pathogens. |

| Approach | Respondents (Type and Number) | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Household Survey (Structured questionnaire) | 67 households

|

|

| Observations (Checklist) | 15 households

|

|

| FGDs (Semi-structured questions) | 15 participants

|

|

| KIIs (Semi-structured questions) | 5 representatives

|

|

| Type of Samples (n) | Prioritized Samples Collected |

|---|---|

| Food (70) * BGPH: 30 † NBGPs: 40 | Dried banana, coconut waste, dried fish, dried pork, green vegetables (leftovers), jackfruits, leftover fish, leftover pork, mango, orange, potato, raw meat, rice, sugar cane, tomato, and vegetable waste/garbage. |

| Household surface (376) BGPHs: 208 NBGPs: 168 | Bat roosts, basket over food, ceramic container for bat guano, clothes (near bat roost, in and out house), cooking table, cover on rice, hat for collecting bat guano, outside table, plate (inside in kitchen uncovered and outside kitchen), railing, table, fridge, table near stove, toilet door, upstairs floor, upstairs table, and water containers surfaces (outside and in the kitchen). |

| Water (75) BGPHs: 40 NBGPs: 35 | Drinking water (39samples), pond water used for vegetable gardening (36 samples) |

| Approach | Respondents (Type and Number) | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Household Survey (Structured questionnaire) | 55 households

|

|

| Observations (Checklist) | 55 households

|

|

| FGDs (Semi-structured questions) | 20 participants

|

|

| KIIs (Semi-structured questions) | 6 respondents

|

|

| Household surface sample testing | 60 samples

|

|

| KAP (n = 67) | Validation (n = 55) Like the New Demographic Tables | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BGP (n = 16) | NBGP (n = 51) | BGP (n = 17) | NBGP (n = 38) | |

| Sex | ||||

| 7 | 23 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 28 | 10 | 30 |

| Average Age (years) | ||||

| 62 | 53 | 63 | 64 |

| 58 | 56 | 56 | 60 |

| Education | ||||

| 16 | 34 | 12 | 28 |

| 0 | 17 | 5 | 10 |

| Main income source | ||||

| 10 | 24 | 8 | 16 |

| 5 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| 0 | 18 | 0 | 13 |

| 1 | 9 | 2 | 8 |

| Distance home to bat roost | ||||

| 16 | 21 | 17 | 24 |

| 0 | 14 | 0 | 14 |

| 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| Workforce at bat farm (total number) | ||||

| 28 | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| 23 | 0 | 13 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Direct Exposure (n = 16) | Description of Results |

|---|---|

| Use of PPE (n = 16) |

|

| Hygiene (n = 67) |

|

| Contamination (n = 67) |

|

| Human–bat–animal interaction (n = 16) |

|

| Bat–animal interaction (n = 16) |

|

| Gender (n = 16) |

|

| No | Types of Samples | No. of Sample | Lab Results (%) | Detected Virus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bat feces | 146 | 18% | Alphacoronavirus |

| 2 | Bat urine | 116 | 16.3% | Alphacoronavirus |

| 3 | Food | 70 | 1.4% | Alphacoronavirus/IBV |

| 4 | Household surface | 376 | 2.9% | Alphacoronavirus/IBV |

| 5 | Water | 75 | 0 |

| Key Behaviors | Before Intervention (KAP) | p-Value | After Intervention (Validation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BGPs’ and NBGPs’ awareness of zoonotic diseases | 19.4% (13/67) | <0.001 | 100% (51/51) |

| BGP women-led decision-making on bat guano farm operations | 43.7% (7/16) | 0.732 | 52.9% (9/17) |

| BGPs wore a full set of protective equipment | 25% (4/16) | 0.002 | 83.2% (14/17) |

| BGPs’ handwashing with soap after contact with bats, guanos and urine | 81.2% (13/16) | 1.000 | 88.2% (45/55) |

| BGPs’ and NBGPs’ covering of foods from contact of bats and livestock | 19.4% (13/67) | <0.001 | 98.2% (54/55) |

| BGPs’ and NBGPs’ covering of water sources from contacts bats and livestock | 44.8% (30/67) | 0.070 | 62.5% (34/55) |

| BGPs’ safe storage of harvested bat guano | 6.6% (1/16) | 0.017 | 47.1% (8/17) |

| BGPs’ and NGBPs’ wiping of household surfaces with soaps or disinfectant | 9% (6/67) | <0.001 | 85.5% (47/55) |

| BGPs’ and NBGPs’ safe disposal of dead bats (burning or burying) | 12.5% (2/16) | <0.001 | 75% (15/20) |

| BGPs’ prevention of domestic animals from roaming under the bat roosts | 18.8% (3/16) | <0.001 | 82.4% (14/17 *) |

| Type of HH Surfaces | No. of Samples | Level of Soiling (Average) | Reduction (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | |||

| 1. Brick meal tables | 16 | 2901 | 237 | 91.8% |

| 2. Metal kitchen cabinets | 2 | 1521 | 162 | 89.4% |

| 3. Metal meal tables | 6 | 1205 | 139 | 88.4% |

| 4. Water jar covers (Zinc) | 4 | 3197 | 855 | 73.1% |

| 5. Wooden relaxing tables | 26 | 2096 | 742 | 64.6% |

| 6. Wooden meal tables | 6 | 561 | 246 | 56.1% |

| Mean | 60 | 11,481 | 2381 | 79.3% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sok, D.; Vong, S.; Lorn, S.; Srey, C.; Kenyon, M.; Ghersi, B.M.; Burgess, T.L.; Griffiths, M.; Ali, D.; Faustman, E.M.; et al. Community Participatory Approach to Design, Test, and Implement Interventions That Reduce Risk of Bat-Borne Disease Spillover: A Case Study from Cambodia. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2026, 11, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed11010007

Sok D, Vong S, Lorn S, Srey C, Kenyon M, Ghersi BM, Burgess TL, Griffiths M, Ali D, Faustman EM, et al. Community Participatory Approach to Design, Test, and Implement Interventions That Reduce Risk of Bat-Borne Disease Spillover: A Case Study from Cambodia. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2026; 11(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed11010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleSok, Dou, Sreytouch Vong, Sophal Lorn, Chanthy Srey, Madeline Kenyon, Bruno M. Ghersi, Tristan L. Burgess, Marcia Griffiths, Disha Ali, Elaine M. Faustman, and et al. 2026. "Community Participatory Approach to Design, Test, and Implement Interventions That Reduce Risk of Bat-Borne Disease Spillover: A Case Study from Cambodia" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 11, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed11010007

APA StyleSok, D., Vong, S., Lorn, S., Srey, C., Kenyon, M., Ghersi, B. M., Burgess, T. L., Griffiths, M., Ali, D., Faustman, E. M., Gold, E., Gass, J. D., Nutter, F. B., Amuguni, J. H., & Peterson, J. (2026). Community Participatory Approach to Design, Test, and Implement Interventions That Reduce Risk of Bat-Borne Disease Spillover: A Case Study from Cambodia. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 11(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed11010007