Operational Research Improves Compliance with Treatment Guidelines for Empirical Management of Urinary Tract Infection: A Before-and-After Study from a Primary Health Facility in Ghana

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting

2.2.1. General Setting

2.2.2. Specific Setting

Management of Uncomplicated UTIs at the KBP

Electronic Medical Records

2.2.3. Dissemination of Findings of the Operational Research Study

2.2.4. Recommendations Made and Actions Taken

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Data Collection, Sources, and Variables

Operational Definitions

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

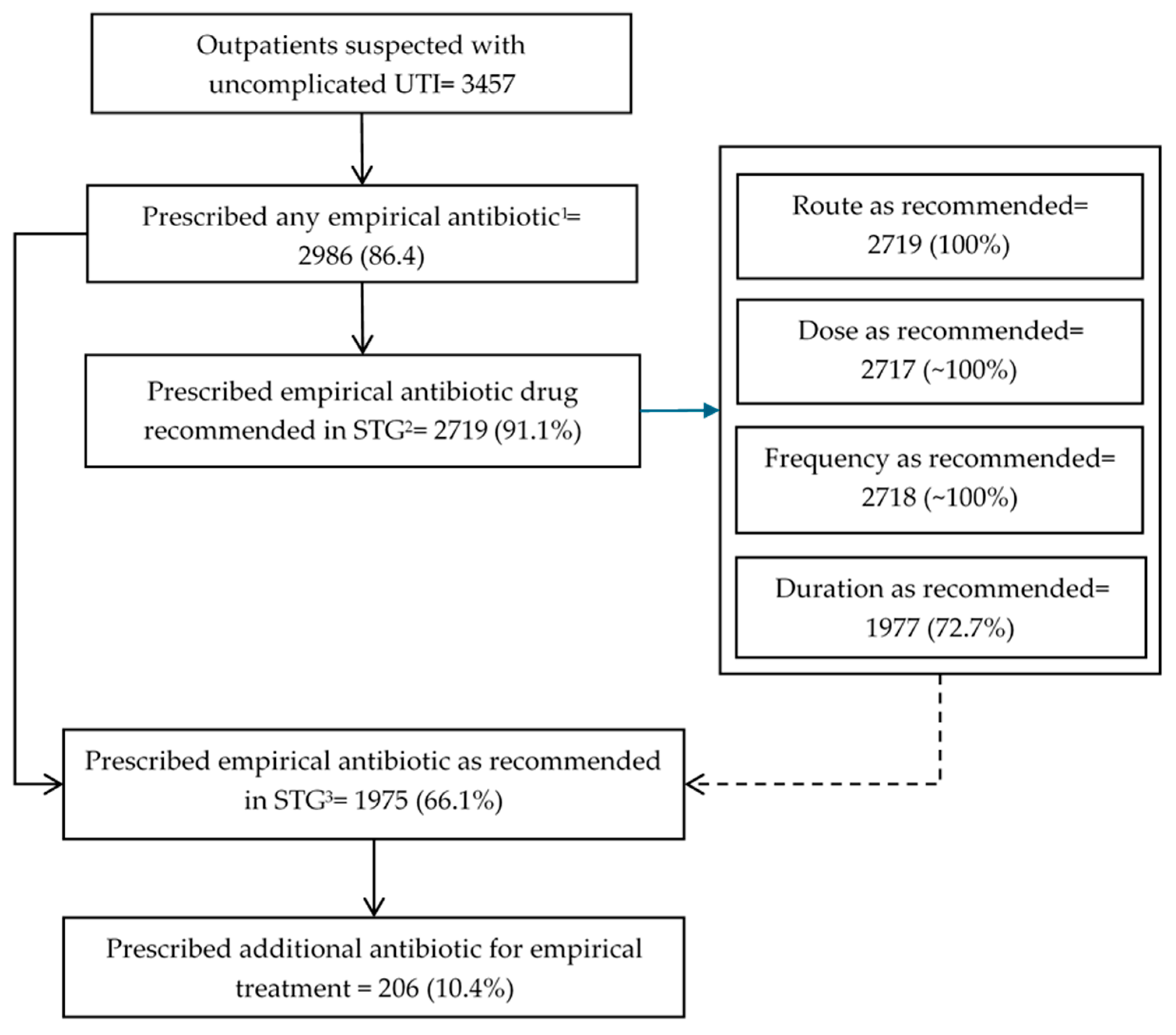

3.2. Prescription of Empirical Antibiotics for UTI Patients

3.3. Distribution of Prescribed Empirical Antibiotics Across the WHO AWaRe Category

3.4. Patient and Prescriber Characteristics Associated with the Prescription of Empirical Antibiotics Not in Line with the STGs

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tandogdu, Z.; Wagenlehner, F. Global Epidemiology of Urinary Tract Infections. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 29, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxman, B. Epidemiology of Urinary Tract Infections: Incidence, Morbidity, and Economic Costs. Am. J. Med. 2002, 113 (Suppl. 1), 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Zhan, J.; Zhang, K.; Chen, H.; Cheng, S. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Urinary Tract Infections from 1990 to 2019: An Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. World J. Urol. 2022, 40, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antinori, S.; Pezzani, M.D. Uncomplicated and Complicated Urinary Tract Infections in Adults: The Infectious Diseases’s Specialist Perspective. In Imaging and Intervention in Urinary Tract Infections and Urosepsis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 17–33. ISBN 978-3-319-68276-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ong Lopez, A.; Tan, C.; Yabon, A.; Masbang, A. Symptomatic Treatment (Using NSAIDS) versus Antibiotics in Uncomplicated Lower Urinary Tract Infection: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Kotsantis, I.K.; Vouloumanou, E.K.; Rafailidis, P.I. Antibiotics versus Placebo in the Treatment of Women with Uncomplicated Cystitis: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Infect. 2009, 58, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Mireles, A.L.; Walker, J.N.; Caparon, M.; Hultgren, S.J. Urinary Tract Infections: Epidemiology, Mechanisms of Infection and Treatment Options. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Hooton, T.M.; Naber, K.G.; Rn Wullt, B.; Colgan, R.; Miller, L.G.; Moran, G.J.; Nicolle, L.E.; Raz, R.; Schaeffer, A.J.; et al. International Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Acute Uncomplicated Cystitis and Pyelonephritis in Women: A 2010 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, e103–e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; LaSala, C. Role of Antibiotic Resistance in Urinary Tract Infection Management: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 225, 550.e1–550.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Grigoryan, L.; Trautner, B. Urinary Tract Infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 167, ITC49–ITC64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulder, M.; Baan, E.; Verbon, A.; Stricker, B.; Verhamme, K. Trends of Prescribing Antimicrobial Drugs for Urinary Tract Infections in Primary Care in the Netherlands: A Population-Based Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isberg, H.K.; Hedin, K.; Melander, E.; Mölstad, S.; Beckman, A. Increased Adherence to Treatment Guidelines in Patients with Urinary Tract Infection in Primary Care: A Retrospective Study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langner, J.L.; Chiang, K.F.; Stafford, R.S. Current Prescribing Practices and Guideline Concordance for the Treatment of Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections in Women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 225, 272.e1–272.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoryan, L.; Zoorob, R.; Wang, H.; Trautner, B.W. Low Concordance With Guidelines for Treatment of Acute Cystitis in Primary Care. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2015, 2, ofv159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durkin, M.J.; Keller, M.; Butler, A.M.; Kwon, J.H.; Dubberke, E.R.; Miller, A.C.; Polgreen, P.M.; Olsen, M.A. An Assessment of Inappropriate Antibiotic Use and Guideline Adherence for Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2018, 5, ofy198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Kung, K.; Au-Doung, P.; Ip, M.; Lee, N.; Fung, A.; Wong, S. Antibiotic Resistance Rates and Physician Antibiotic Prescription Patterns of Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections in Southern Chinese Primary Care. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Chen, Y.; Hang, Y.; Luo, H.; Fang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Cao, X.; Zou, S.; Hu, X.; Hu, L.; et al. Impact of Inappropriate Empirical Antibiotic Treatment on Clinical Outcomes of Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Escherichia Coli: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 26, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabbara, W.K.; Meski, M.M.; Ramadan, W.H.; Maaliki, D.S.; Salameh, P. Adherence to International Guidelines for the Treatment of Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections in Lebanon. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2018, 2018, 7404095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appaneal, H.; Shireman, T.; Lopes, V.; Mor, V.; Dosa, D.; LaPlante, K.; Caffrey, A. Poor Clinical Outcomes Associated with Suboptimal Antibiotic Treatment among Older Long-Term Care Facility Residents with Urinary Tract Infection: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. Ghana National Drugs Programme Urinary Tract Infection. In Standard Treatment Guidelines; Ministry of Health: Accra, Ghana, 2017; pp. 401–403. ISBN 9789988257873. [Google Scholar]

- Zachariah, R.; Stewart, A.G.; Chakaya, J.M.; Teck, R.; Khogali, M.A.; Harries, A.D.; Seeley-Musgrave, C.; Samba, T.; Reeder, J.C. The Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative for Strengthening Health Systems to Tackle Antimicrobial Resistance and Improve Public Health in Low-and-Middle Income Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TDR SORT IT Operational Research and Training. Available online: https://tdr.who.int/activities/sort-it-operational-research-and-training (accessed on 8 December 2023).

- Owusu, H.; Thekkur, P.; Ashubwe-Jalemba, J.; Hedidor, G.K.; Corquaye, O.; Aggor, A.; Steele-Dadzie, A.; Ankrah, D. Compliance to Guidelines in Prescribing Empirical Antibiotics for Individuals with Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infection in a Primary Health Facility of Ghana, 2019-2021. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TDR Communicating Research Findings with a KISS. Available online: https://tdr.who.int/newsroom/news/item/21-06-2021-communicating-research-findings-with-a-kiss (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- UN. Human Population. World Population Prospect. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.PPO.TOTL?locations=GH (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Assan, A.; Takian, A.; Aikins, M.; Akbarisari, A. Universal Health Coverage Necessitates a System Approach: An Analysis of Community-Based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) Initiative in Ghana. Glob. Health 2018, 14, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHIS–Your Access to Healthcare. Available online: http://www.nhis.gov.gh/ (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Christmals, C.D.; Aidam, K. Implementation of the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) in Ghana: Lessons for South Africa and Low-and Middle-Income Countries. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 1879–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems: Tenth Revision. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42980 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Murray, C.J.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llor, C.; Bjerrum, L. Antimicrobial Resistance: Risk Associated with Antibiotic Overuse and Initiatives to Reduce the Problem. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2014, 5, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkor, E.S.; Horlortu, P.Z.; Dayie, N.T.K.D.; Obeng-Nkrumah, N.; Labi, A.K. Community Acquired Urinary Tract Infections among Adults in Accra, Ghana. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 2059–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes in Health-Care Facilities in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. A WHO Practical Toolkit; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah, O.K.O.; Courtenay, A.; Ayisi-Boateng, N.K.; Abuelhana, A.; Opoku, D.A.; Blay, L.K.; Abruquah, N.A.; Osafo, A.B.; Danquah, C.B.; Tawiah, P.; et al. Assessing the Impact of Antimicrobial Stewardship Implementation at a District Hospital in Ghana Using a Health Partnership Model. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 5, dlad084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) Antibiotic Book; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Phamnguyen, T.J.; Murphy, G.; Hashem, F. Single Centre Observational Study on Antibiotic Prescribing Adherence to Clinical Practice Guidelines for Treatment of Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infection. Infect. Dis. Health 2019, 24, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabih, A.; Leslie, S.W. Complicated Urinary Tract Infections; StatPearls Publishing: Petersburg, FA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.J.; Coffey, K.C. Shorter Courses of Antibiotics for Urinary Tract Infection in Men. JAMA 2021, 326, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germanos, G.J.; Trautner, B.W.; Zoorob, R.J.; Salemi, J.L.; Drekonja, D.; Gupta, K.; Grigoryan, L. No Clinical Benefit to Treating Male Urinary Tract Infection Longer Than Seven Days: An Outpatient Database Study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019, 6, ofz216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mode of Delivery | To Whom (Number) | Where | When |

|---|---|---|---|

| Three-minute lightning PowerPoint presentation | MoH stakeholders (32) | The national SORT IT module 4 | October 2022 |

| Published article | Global and national AMS/AMR professional groups (35) | Social media platforms: Whatsapp, Facebook, and LinkedIn | November 2022 |

| Twenty-minute technical PowerPoint presentation | Polyclinic staff and other medical officers (50+) | Polyclinic morning meeting (Online) | January 2023 |

| Ten-minute technical PowerPoint presentation | MoH stakeholders (30) | National SORT IT dissemination programme | July 2023 |

| Poster presentation | Pharmacists from all over Ghana (500+) | Annual General Meeting of Pharmacists | September 2023 |

| Plain language handouts | Polyclinic core management Team (5) | Polyclinic HoD office | December, 2022 |

| Pharmacy students and interns (100) | Polyclinic pharmacy | January 2023 |

| Recommendation | Action Status | Details of Action (When) |

|---|---|---|

| Institute an audit feedback system by leveraging the EMR within a comprehensive antimicrobial stewardship programme | Fully implemented | A clinical audit–feedback system was integrated into the resident training in January 2023. Clinical audit and feedback on malaria and pneumonia management were implemented in September 2023 and March 2024, respectively. The prescribers were presented with the findings and feedback was provided on ways to improve compliance with the STGs. The antimicrobial stewardship committee with a dedicated clinical audit and feedback team is yet to be established, although efforts are far advanced. |

| Determine and address reasons for the poor compliance in this study | Partially implemented | This was performed informally by interviewing the residents and medical officers in February and March 2023. It was discovered that apart from the STGs, other international guidelines are used by prescribers, including the BNF, Medscape, and UpToDate. |

| Systematic monitoring of compliance with STGs for other diseases | Fully implemented | Monitoring of compliance with guidelines in severe malaria and pneumonia completed in September 2023 and March 2024, respectively. |

| Promote similar efforts to assess compliance with STGs across primary care facilities with EMRs | Partially implemented | Ongoing collaborations with 5 other Ghanaian hospitals (Police Hospital, Tema General Hospital, Keta Municipal Hospital, University of Ghana Medical Center, and Cape Coast Teaching Hospital) to determine compliance with guidelines in prescribing for community-acquired pneumonia. |

| Consider revising the STGs on treatment of uncomplicated UTI based on current evidence | Partially implemented | The Ministry of Health is currently reviewing the STGs |

| Characteristics | Before | After | p Value 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) 1 | n | (%) 1 | ||

| Total | 3717 | (100) | 3457 | ||

| Age in years | |||||

| 18–29 | 757 | (20.4) | 730 | (21.1) | 0.130 |

| 30–44 | 919 | (24.7) | 775 | (22.4) | |

| 45–59 | 804 | (21.6) | 787 | (22.8) | |

| ≥60 | 1237 | (33.3) | 1165 | (33.7) | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 1064 | (28.6) | 974 | (28.2) | 0.672 |

| Female | 2653 | (71.4) | 2483 | (71.8) | |

| NHIS | |||||

| Yes | 2920 | (78.5) | 2718 | (78.6) | 0.473 |

| No | 797 | (21.5) | 739 | (21.4) | |

| Comorbidities 2 | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 621 | (16.7) | 644 | (18.6) | 0.016 |

| Hypertension | 1231 | (33.1) | 1327 | (38.4) | <0.001 |

| Routine urine examination | |||||

| Not done | 1137 | (30.5) | 1138 | (32.9) | 0.007 |

| Done | 2574 | (69.3) | 2319 | (67.1) | |

| Missing | 6 | (0.2) | |||

| Prescriber sex | |||||

| Male | 2084 | (56.0) | 1783 | (51.6) | <0.001 |

| Female | 1623 | (43.7) | 1674 | (48.4) | |

| Missing | 10 | (0.3) | |||

| Prescriber rank 3 | |||||

| Physician Assistant | 36 | (1.0) | 32 | (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Medical Officer | 1616 | (43.5) | 1466 | (42.4) | |

| Senior/Principal/Deputy Chief/Chief Medical Officer | 348 | (9.4) | 554 | (16.0) | |

| Resident/Senior Resident | 1136 | (30.6) | 1103 | (31.9) | |

| Specialist/Senior Specialist/Consultant | 469 | (15.6) | 302 | (8.7) | |

| Particulars | Before | After | p Value 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n | (%) 1 | N | n | (%) 1 | ||

| Prescribed any empirical antibiotic | 3717 | 3073 | (83) | 3457 | 2986 | (86) | <0.001 |

| Prescribed the empirical antibiotic recommended in the STGs 3 | 3073 | 2714 | (88) | 2986 | 2719 | (91) | <0.001 |

| Prescribed the empirical antibiotic recommended in the STGs at the correct dose 4 | 2714 | 2712 | (~100) | 2719 | 2717 | (~100) | 0.996 |

| Prescribed the empirical antibiotic recommended in the STGs for the correct duration 4 | 2714 | 1848 | (68) | 2719 | 1977 | (73) | <0.001 |

| Prescribed the empirical antibiotic recommended in the STGs in the correct route 4 | 2714 | 2712 | (~100) | 2719 | 2719 | (100) | 0.156 |

| Prescribed the empirical antibiotic recommended in the STGs in the correct frequency 4 | 2714 | 2712 | (~100) | 2719 | 2718 | (~100) | 0.561 |

| Prescribed the empirical antibiotic in line with the STGs 5 | 3073 | 1847 | (60) | 2986 | 1975 | (66) | <0.001 |

| Antimicrobials | Before, N = 3378 | After, N = 3491 | p Value b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) a | n | (%) a | ||

| Access | |||||

| Total | 381 | (11.2) | 577 | (16.5) | <0.001 |

| Tinidazole | 119 | (3.5) | 121 | (3.5) | 0.898 |

| Nitrofurantoin | 90 | (2.7) | 142 | (4.1) | <0.001 |

| Doxycycline | 88 | (2.6) | 157 | (4.5) | <0.001 |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 52 | (1.5) | 22 | (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Secnidazole | 20 | (0.6) | 38 | (1.1) | 0.025 |

| Metronidazole | 8 | (0.2) | 72 | (2.0) | <0.001 |

| Clindamycin | 2 | (0.1) | 13 | (0.4) | 0.005 |

| Amoxicillin | 1 | (<0.1) | 7 | (0.2) | 0.038 |

| Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim | 1 | (<0.1) | 5 | (0.1) | 0.111 |

| Watch | |||||

| Total | 2997 | (88.8) | 2914 | (83.5) | <0.001 |

| Cefuroxime | 1831 | (54.2) | 1479 | (42.4) | <0.001 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1036 | (30.7) | 1252 | (35.9) | <0.001 |

| Cefixime | 38 | (1.1) | 86 | (2.5) | <0.001 |

| Ceftriaxone | 33 | (1.0) | 17 | (0.5) | 0.017 |

| Levofloxacin | 31 | (0.9) | 18 | (0.5) | 0.048 |

| Azithromycin | 23 | (0.7) | 50 | (1.4) | 0.002 |

| Cefpodoxime | 3 | (0.1) | 3 | (0.1) | 0.968 |

| Clarithromycin | 2 | (0.1) | 9 | (0.2) | 0.040 |

| Characteristics | Total | Empirical Antibiotics not in Line with STGs | Unadjusted b | Adjusted c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) a | PR | (95% CI) | aPR | (95% CI) | ||

| Total | 2986 | 1011 | (33.9) | ||||

| Age in years | |||||||

| 18–29 | 628 | 168 | (26.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 30–44 | 660 | 216 | (32.7) | 1.2 | (1.0–1.4) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.3) |

| 45–59 | 685 | 252 | (36.8) | 1.4 | (1.2–1.6) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.3) |

| ≥60 | 1013 | 375 | (37.0) | 1.4 | (1.2–1.6) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.3) |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 844 | 689 | (81.6) | 5.4 | (4.9–6.0) | 5.4 | (4.9–6.1) |

| Female | 2142 | 322 | (15.0) | 1 | 1 | ||

| NHIS | |||||||

| Yes | 2568 | 851 | (33.1) | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 418 | 160 | (38.3) | 1.2 | (1.0–1.3) | 1.0 | (0.8–1.1) |

| Comorbidities d | |||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 537 | 181 | (33.7) | 1.0 | (0.9–1.1) | 1.1 | (1.0–1.2) |

| Hypertension | 1142 | 419 | (36.7) | 1.1 | (1.0–1.3) | 1.0 | (0.9–1.1) |

| Routine urine examination | |||||||

| Done | 960 | 333 | (34.7) | 1.0 | (0.9–1.2) | 1.0 | (1.0–1.1) |

| Not done | 2026 | 678 | (33.5) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Prescriber gender | |||||||

| Male | 1537 | 523 | (34.0) | 1.0 | (0.9–1.1) | 1.0 | |

| Female | 1449 | 488 | (33.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Prescriber rank e | |||||||

| Physician Assistant | 25 | 10 | (40.0) | 1.2 | (0.8–2.0) | 1.3 | (0.8–2.1) |

| Medical Officer | 1269 | 439 | (34.6) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.2) | 1.0 | (0.9–1.1) |

| Senior/Principal/Deputy Chief/Chief Medical Officer | 484 | 167 | (34.5) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.2) | 1.0 | (0.9–1.1) |

| Resident/Senior Resident | 957 | 310 | (32.4) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Specialist/Snr Specialist/Consultant | 251 | 85 | (33.9) | 1.0 | (0.9–1.3) | 1.0 | (0.9–1.2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boateng, E.; Owusu, H.; Thekkur, P.; Hedidor, G.K.; Corquaye, O.; Opare-Addo, M.N.A.; Nkansah, F.A.; Vandyck-Sey, P.; Ankrah, D.; Ofei-Palm, C.N.K. Operational Research Improves Compliance with Treatment Guidelines for Empirical Management of Urinary Tract Infection: A Before-and-After Study from a Primary Health Facility in Ghana. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10090259

Boateng E, Owusu H, Thekkur P, Hedidor GK, Corquaye O, Opare-Addo MNA, Nkansah FA, Vandyck-Sey P, Ankrah D, Ofei-Palm CNK. Operational Research Improves Compliance with Treatment Guidelines for Empirical Management of Urinary Tract Infection: A Before-and-After Study from a Primary Health Facility in Ghana. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2025; 10(9):259. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10090259

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoateng, Elizabeth, Helena Owusu, Pruthu Thekkur, George Kwesi Hedidor, Oksana Corquaye, Mercy N. A. Opare-Addo, Florence Amah Nkansah, Priscilla Vandyck-Sey, Daniel Ankrah, and Charles Nii Kwadee Ofei-Palm. 2025. "Operational Research Improves Compliance with Treatment Guidelines for Empirical Management of Urinary Tract Infection: A Before-and-After Study from a Primary Health Facility in Ghana" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 10, no. 9: 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10090259

APA StyleBoateng, E., Owusu, H., Thekkur, P., Hedidor, G. K., Corquaye, O., Opare-Addo, M. N. A., Nkansah, F. A., Vandyck-Sey, P., Ankrah, D., & Ofei-Palm, C. N. K. (2025). Operational Research Improves Compliance with Treatment Guidelines for Empirical Management of Urinary Tract Infection: A Before-and-After Study from a Primary Health Facility in Ghana. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 10(9), 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10090259