High Levels of Community Support for Mansonellosis Interventions in an Endemic Area of the Brazilian Amazon

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

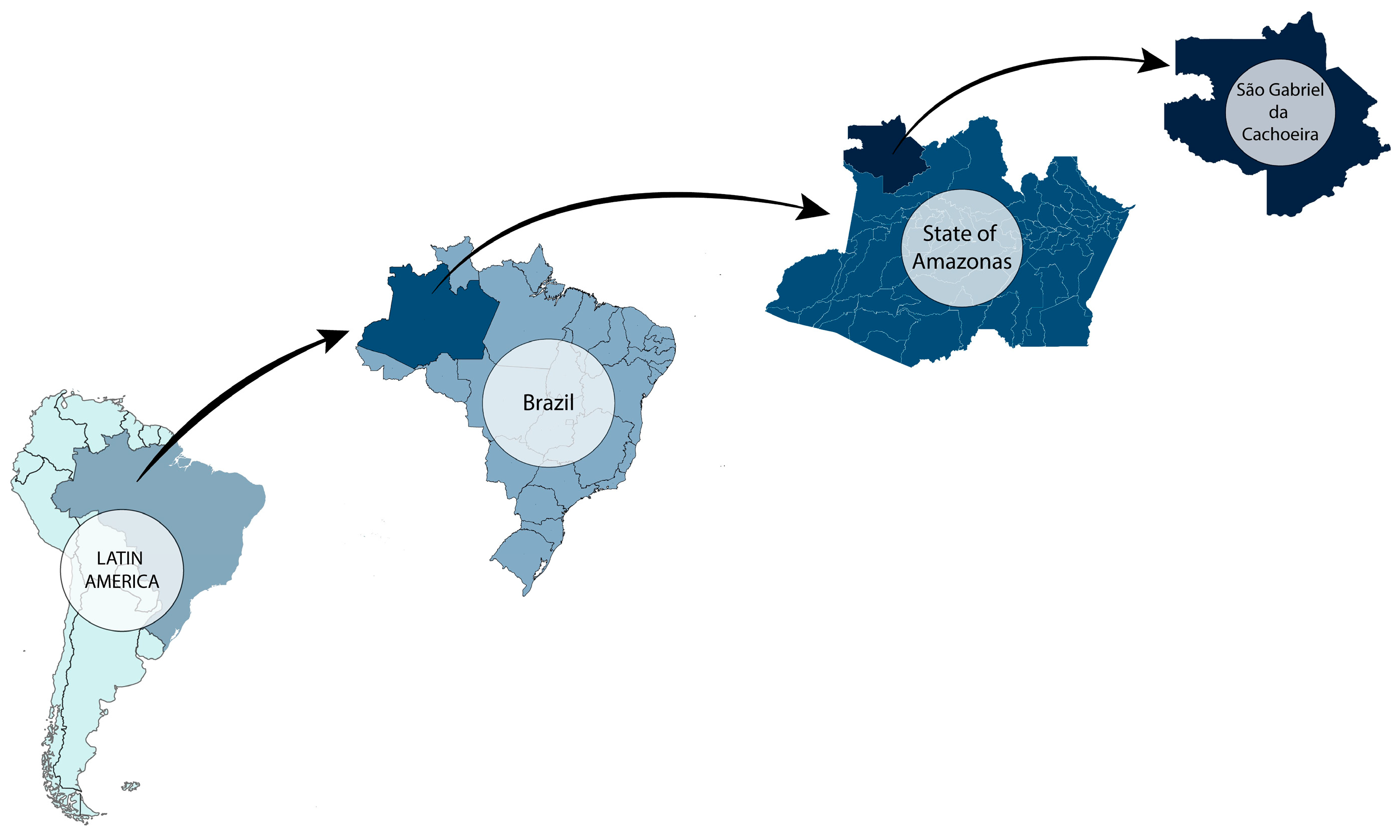

2.1. The Study Site

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Profile of Surveyed SGC Residents

3.2. SGC Community Support for Mansonellosis and SHT Treatment Programs

4. Discussion

4.1. High Levels of Community Member Willingness to Participate in Anthelmintic Disease Programs Suggests Such Programs Could Work Efficiently in SGC

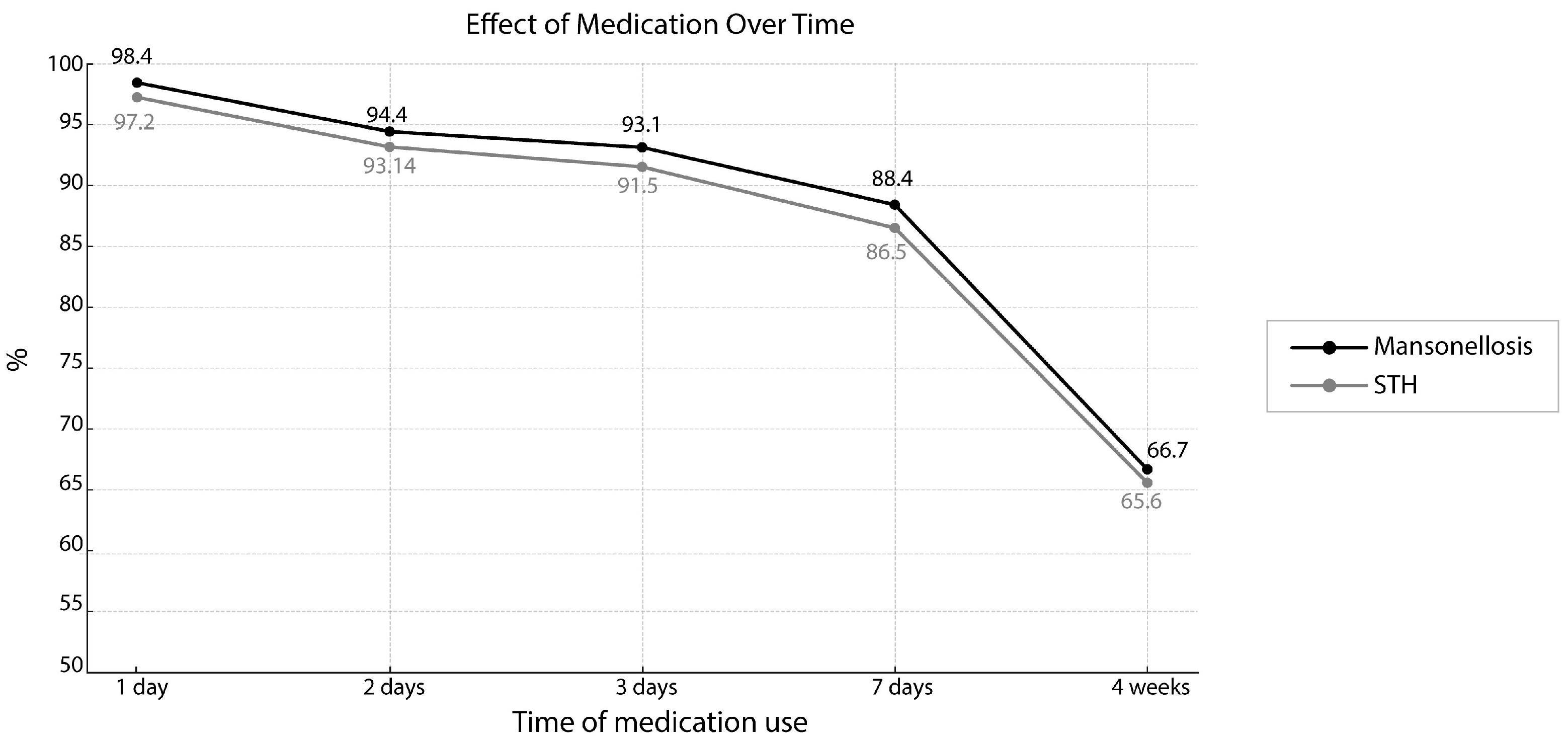

4.2. Community Participation in Mansonellosis and STH Treatment Programs Can Likely Be Enhanced with Fast-Acting Drug Treatments

4.3. Community Participation in Mansonellosis and STH Treatment Programs Can Likely Be Enhanced with Diagnostic Testing and Prevalence Surveys

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ta-Tang, T.H.; Crainey, J.L.; Post, R.J.; Luz, S.L.; Rubio, J.M. Mansonellosis: Current perspectives. Res. Rep. Trop. Med. 2018, 9, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares da Silva, L.B.; Crainey, J.L.; Ribeiro da Silva, T.R.; Suwa, U.F.; Vicente, A.C.; Medeiros, J.F.; Pessoa, F.A.; Luz, S.L. Molecular verification of new world Mansonella perstans parasitemias. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017, 23, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crainey, J.L.; Costa, C.H.A.; Leles, L.F.; Silva, T.R.R.; Aquino, L.H.N.; Santos, Y.V.S.D.; Conteville, L.C.; Pessoa, F.A.C.; Cortés, J.J.C.; Vicente, A.C.P.; et al. Deep-sequencing reveals occult mansonellosis co-infections in residents from the Brazilian Amazon village of São Gabriel da Cachoeira. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 1990–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portela, C.S.; Araújo, C.P.M.; Sousa, P.M.; Simão, C.L.G.; Oliveira, J.C.S.; Crainey, J.L. Filarial disease in the Brazilian Amazon and emerging opportunities for treatment and control. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector Borne Dis. 2023, 5, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adami, Y.L.; Herzog, M.M. Mansonelose no médio rio Purus (Amazonas). Rev. Eletrônica De Comun. Informação Inovação Em Saúde 2008, 2, 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros, J.F.; Py-Daniel, V.; Barbosa, U.C.; Izzo, T.J. Mansonella ozzardi in Brazil: Prevalence of infection in riverine communities in the Purus region, in the state of Amazonas. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2009, 104, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.; Pessoa, F.A.; Medeiros, M.B.; Andrade, E.V.; Medeiros, J.F. Mansonella ozzardi in Amazonas, Brazil: Prevalence and distribution in the municipality of Coari, in the middle Solimões River. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2010, 105, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.U.; Crainey, J.L.; Gobbi, F.G. The search for better treatment strategies for mansonellosis: An expert perspective. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2023, 24, 1685–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela, C.S.; Suwa, U.F.; Oliveira, J.C.S.; Simão, C.L.G.; Crainey, J.L. Monitoramento e controle das doenças filariais na região amazônica brasileira. In MCRF Planejamento e Políticas De Saúde Na Amazônia, 1st ed.; Série Saúde & Amazônia, v.31, E-book: PDF; Tobias, R., Leles, F.G., Lima, M.C.R.F., Eds.; Editora Rede UNIDA: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2024; 320p, ISBN 978-65-5462-140-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrah, L.B.; Phillips, R.O.; Pfarr, K.; Klarmann-Schulz, U.; Opoku, V.S.; Nausch, N.; Owusu, W.; Mubarik, Y.; Sander, A.L.; Lämmeret, C.; et al. The efficacy of doxycycline treatment on Mansonella perstans infection: An open-label, randomized trial in Ghana. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 101, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, Y.I.; Dembele, B.; Diallo, A.A.; Lipner, E.M.; Doumbia, S.S.; Coulibaly, S.Y.; Konate, S.; Diallo, D.A.; Yalcouye, D.; Kubofcik, Y. A randomized trial of doxycycline for Mansonella perstans infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1448–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrens, A.; Hoerauf, A.; Hübner, M.P. Current perspective of new anti-Wolbachial and direct-acting macrofilaricidal drugs as treatment strategies for human filariasis. GMS Infect. Dis. 2022, 10, Doc02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risch, F.; Kazakov, A.; Specht, S.; Pfarr, K.; Fischer, P.U.; Hoerauf, A.; Hübner, M.P. The long and winding road towards new treatments against lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis. Trends Parasitol. 2024, 40, 829–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ta-Tang, T.H.; Luz, S.L.; Crainey, J.L.; Rubio, J.M. An overview of the management of mansonellosis. Res. Rep. Trop. Med. 2021, 12, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutono, N.; Basáñez, M.G.; James, A.; Stolk, W.A.; Makori, A.; Kimani, T.N.; Hollingsworth, T.D.; Vasconcelos, A.; Dixon, M.A.; Vlas, S.J.; et al. Elimination of transmission of onchocerciasis (river blindness) with long-term ivermectin mass drug administration with or without vector control in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e771–e782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamgno, J.; Djeunga, H.N. Progress towards global elimination of lymphatic filariasis. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e1108–e1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakwo, T.; Oguttu, D.; Ukety, T.; Post, R.; Bakajika, D. Onchocerciasis elimination: Progress and challenges. Res. Rep. Trop. Med. 2020, 118, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdan, P.M.; Lamberton, P.H.L.; Fenwick, A.; Addiss, D.G. Soil-transmitted helminth infections. Lancet 2018, 391, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotez, P.J.; Fenwick, A.; Molyneux, D.H. Collateral benefits of preventive chemotherapy—Expanding the war on neglected tropical diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 2389–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotez, P.J.; Fenwick, A.; Ray, S.E.; Hay, S.I.; Molyneux, D.H. Rapid impact 10 years after: The first decade (2006–2016) of integrated neglected tropical disease control. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotez, P.J.; Lo, N.C. Neglected tropical diseases: Public health control programs and mass drug administration. In Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Diseases; Hill, D., Ryan, E., Aronson, N., Endy, P., Solomon, T., Eds.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 209–213. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, L.; Stolk, W.A.; Farrell, S.H.; Hollingsworth, T.D. Measuring and modelling the effects of systematic non-adherence to mass drug administration. Epidemics 2017, 18, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnen, M.; Plaisier, A.P.; Alley, E.S.; Nagelkerke, N.J.; Van Oortmarssen, G.J.; Habbema, J.D. Can ivermectin mass treatments eliminate onchocerciasis in Africa? Bull. World Health Organ. 2002, 80, 384–391. [Google Scholar]

- Wanji, S.; Nji, T.M.; Hamill, L.; Dean, L.; Ozan, K.; Abdel, J.; Njouendou, R.A.; Abong, E.D.O.; Amuam, A.; Kanya, R. Implementation of test-and-treat with doxycycline and temephos ground larviciding as alternative strategies for accelerating onchocerciasis elimination in an area of loiasis co-endemicity: The Countdown consortium multi-disciplinary study protocol. Parasites Vectors 2019, 12, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katabarwa, M.N.; Griswold, E.; Habomugisha, P.; Eyamba, A.; Byamukama, E.; Nwane, P.; Khainza, A.; Bernard, L.; Weiss, P.; Richards, F.O. Comparison of reported and survey-based coverage in onchocerciasis programs over a period of 8 years in Cameroon and Uganda. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 100, 1208–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmakar, P.R.; Mitra, K.; Chatterjee, A.; Jana, P.K.; Bhattacharya, S.; Lahiri, S.K. A study on coverage, compliance and awareness about mass drug administration for elimination of lymphatic filariasis in a district of West Bengal, India. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2011, 48, 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, M.U.; Crainey, J.L.; Luz, S.L. Mansonella ozzardi. Trends Parasitol. 2021, 37, 90–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, N.F.; Aybar, C.A.V.; Juri, M.J.D.; Ferreira, M.U. Mansonella ozzardi: A neglected New World filarial nematode. Pathog. Glob. Health 2016, 110, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basano, S.A.; Fontes, G.; Medeiros, J.F.; Camargo, J.S.A.A.C.; Vera, L.J.S.; Araújo, M.P.P.; Parente, M.S.P.; Ferreira, R.G.M.; Crispim, P.T.B.; Camargo, L.M.A. Sustained clearance of Mansonella ozzardi infection after treatment with ivermectin in the Brazilian Amazon. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014, 90, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basano, S.A.; Camargo, J.D.S.A.A.; Fontes, G.; Pereira, A.R.; Medeiros, J.F.; Oliveira, L.M.C.; Ferreira, R.G.M.; Camargo, L.M.A. Phase III clinical trial to evaluate ivermectin in the reduction of Mansonella ozzardi infection in the Brazilian Amazon. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 98, 786–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro De Geografia E Estatística (IBGE). Censo Demográfico 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/trabalho/22827-censo-demografico-2022.html (accessed on 20 February 2025). (In Portuguese)

- Rios, L.; Cutolo, S.A.; Giatti, L.L.; Castro, M.; Rocha, A.A.; Toledo, R.F.; Pelicioni, M.C.F.; Barreira, L.P.; Santos, J.G. Prevalência de parasitos intestinais e aspectos socioambientais em comunidade indígena no Distrito de Iauaretê, Município de São Gabriel da Cachoeira (AM), Brasil. Saúde E Soc. 2007, 16, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coura, J.R.; Willcox, H.P.; Tavares, A.M.; Paiva, D.D.; Fernandes, O.; Rada, E.L.; Perez, E.P.; Borges, L.C.; Hidalgo, M.E.; Nogueira, M.L. Epidemiological, social, and sanitary aspects in an area of the Rio Negro, State of Amazonas, with special reference to intestinal parasites and Chagas’ disease. Cad. Saude Publica 1994, 10, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.R.R.D.; Narzetti, L.H.A.; Crainey, J.L.; Costa, C.H.; Santos, Y.V.S.D.; Leles, L.F.O.; Pessoa, F.A.C.; Vicente, A.C.P.; Luz, S.L.B. Molecular detection of Mansonella mariae incriminates Simulium oyapockense as a potentially important bridge vector for Amazon-region zoonoses. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2022, 98, 105200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romão, R.S.T.; Crainey, J.L.; Costa, P.F.A.; Costa, C.H.; Santos, Y.V.S.D.; Leles, L.F.O.; Pessoa, F.A.C.; Vicente, A.C.P.; Luz, S.L.B. Blackflies in the ointment: O. volvulus vector biting can be significantly reduced by the skin-application of mineral oil during human landing catches. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongololo, G.; Funsanani, M.; Musaya, J.; Juziwelo, L.T.; Furu, P. An assessment of implementation and effectiveness of mass drug administration for prevention and control of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths in selected southern Malawi districts. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 19, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.; Togbevi, I.C.; Ibikounlé, M.; Avokpaho, E.F.; Walson, J.L.; Means, A.R. Soil-transmitted helminth surveillance in Benin: A mixed-methods analysis of factors influencing non-participation in longitudinal surveillance activities. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0010984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibikounlé, M.; Onzo-Aboki, A.; Doritchamou, J.; Tougoué, J.J.; Boko, P.M.; Savassi, B.S.; Siko, E.J.; Daré, A.; Batcho, W.; Massougbodji, A.; et al. Results of the first mapping of soil-transmitted helminths in Benin: Evidence of countrywide hookworm predominance. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanji, S.; Kengne-Ouafo, J.A.; Esum, M.E.; Chounna, P.W.N.; Tendongfor, N.; Adzemye, B.F.; Eyong, J.E.E.; Jato, I.; Datchoua-Poutcheu, F.R.; Kah, E.; et al. Situation analysis of parasitological and entomological indices of onchocerciasis transmission in three drainage basins of the rain forest of South West Cameroon after a decade of ivermectin treatment. Parasites Vectors 2015, 8, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senyonjo, L.; Oye, J.; Bakajika, D.; Biholong, B.; Tekle, A.; Boakye, D.; Schmidt, E.; Elhassan, E. Factors Associated with Ivermectin Non-Compliance and Its Potential Role in Sustaining Onchocerca volvulus Transmission in the West Region of Cameroon. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, J.D.; Tendongfor, N.; Esum, M.; Johnston, K.L.; Langley, R.S.; Ford, L.; Faragher, B.; Specht, S.; Mand, S.; Hoerauf, A.; et al. Macrofilaricidal activity after doxycycline only treatment of Onchocerca volvulus in an area of Loa loa co-endemicity: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2010, 4, e660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nditanchou, R.; Dixon, R.; Atekem, K.; Akongo, S.; Biholong, B.; Ayisi, F.; Nwane, P.; Wilhelm, A.; Basnet, S.; Selby, R.; et al. Acceptability of test and treat with doxycycline against Onchocerciasis in an area of persistent transmission in Massangam Health District, Cameroon. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrer, A.; Wanji, S.; Obie, E.D.; Nji, T.M.; Hamill, L.; Ozano, K.; Piotrowski, H.; Dean, L.; Njouendou, A.J.; Ekanya, R. Why onchocerciasis transmission persists after 15 annual ivermectin mass drug administrations in South-West Cameroon. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e003248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, J.; Basáñez, M.G.; O’Hanlon, S.J.; Tekle, A.H.; Wanji, S.; Zouré, H.G.; Rebollo, M.P.; Pullan, R.L. Identifying co-endemic areas for major filarial infections in sub-Saharan Africa: Seeking synergies and preventing severe adverse events during mass drug administration campaigns. Parasites Vectors 2018, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suwa, U. Investigação Diagnóstica de Pacientes com Mansonelose Submetidos ao Tratamento com Ivermectina no Município de São Gabriel da Cachoeira, Amazonas. Master´s Thesis, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Rio De Janeiro, Brazil, 2017. Available online: https://bdtd.ibict.br/vufind/Record/CRUZ_0a81cd6bf20a5677179499f54c11e207 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Bakowski, M.A.; Shiroodi, R.K.; Liu, R.; Olejniczak, J.; Yang, B.; Gagaring, K.; Guo, H.; White, P.H.; Chappell, L.; Debec, A.; et al. Discovery of short-course anti-wolbachial quinazolines for elimination of filarial worm infections. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaav3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, J.F.; Almeida, T.A.P.; Silva, L.B.T.; Rubio, J.M.; Crainey, J.L.; Pessoa, F.A.C.; Luz, S.L.B. A field trial of a PCR-based Mansonella ozzardi diagnosis assay detects high-levels of submicroscopic M. ozzardi infections in both venous blood samples and FTA® card dried blood spots. Parasites Vectors 2015, 8, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, D.K.; Otchere, J.; Sumboh, J.G.; Odame, A.; Joseph, O.; Asemanyi-Mensah, K.; Boakye, D.A.; Gass, K.M.; Long, E.F.; Ahorlu, C.S. Finding and eliminating the reservoirs: Engage and treat, and test and treat strategies for lymphatic filariasis programs to overcome endgame challenges. Front. Trop. Dis. 2022, 3, 953094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunt, M.W.; Crainey, J.L. AI sees an end to filariasis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Dacal, E.; Díez, N.; Carmona, C.; Martin Ramirez, A.; Barón Argos, L.; Bermejo-Peláez, D.; Caballero, C.; Cuadrado, D.; Darias-Plasencia, O.; et al. Edge Artificial Intelligence (AI) for real-time automatic quantification of filariasis in mobile microscopy. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 105 | 32.8 |

| Female | 215 | 67.2 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–28 | 88 | 27.5 |

| 29–39 | 85 | 26.6 |

| 40–50 | 60 | 18.8 |

| 51–60 | 45 | 14.1 |

| >60 | 42 | 13.1 |

| Race/Skin Color | ||

| White | 7 | 2.2 |

| Black | 2 | 0.6 |

| Brown | 17 | 5.3 |

| Indigenous | 294 | 91.9 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 134 | 41.9 |

| Married | 100 | 31.3 |

| Widower | 17 | 5.3 |

| Divorced | 6 | 1.9 |

| Others | 63 | 19.7 |

| Level of education (years) | ||

| Between 0 and 9 | 68 | 21.25 |

| ≥10 | 252 | 78.8 |

| Variables | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Work/occupation | ||

| Farmer | 59 | 18.4 |

| Civil servant | 64 | 20.0 |

| Housewife | 56 | 17.5 |

| Student | 10 | 3.1 |

| Retiree | 30 | 9.4 |

| Unemployed | 40 | 12.5 |

| Other services | 61 | 19.1 |

| Family income | ||

| Less than 3 minimum wages | 276 | 86.3 |

| ≥3 minimum wages | 44 | 13.8 |

| Nº Number of residents in the household | ||

| Up to 4 people | 128 | 40.0 |

| 5 or more people | 192 | 60.0 |

| Time spent at the address | ||

| 0–5 years | 98 | 30.6 |

| 6–10 years | 60 | 18.8 |

| >10 years | 162 | 50.6 |

| Neighborhood | ||

| Areal | 82 | 25.6 |

| Dabaru | 37 | 11.6 |

| Praia | 113 | 35.3 |

| Tiago Montalvo | 88 | 27.5 |

| Economic situation | ||

| A or B1 or B2 or C1 | 62 | 19.4 |

| C2 or D-E | 258 | 80.6 |

| STH | Mansonellosis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self | Family Member | Self | Family Member | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| 1 day | 315 | 98.4 | 314 | 98.1 | 1 day | 311 | 97.2 | 308 | 96.25 |

| 2 days | 302 | 94.4 | 302 | 94.3 | 2 days | 298 | 93.14 | 294 | 91.8 |

| 3 days | 298 | 93.1 | 295 | 92.1 | 3 days | 293 | 91.5 | 289 | 90.3 |

| 7 days | 283 | 88.4 | 280 | 87.5 | 7 days | 277 | 86.5 | 278 | 86.8 |

| 4 weeks | 210 | 66.7 | 206 | 64.3 | 4 weeks | 204 | 65.6 | 206 | 64.3 |

| STH | Mansonellosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Regimenn | p-Value | p-Value (Family Member) | p-Value | p-Value (Family Member) |

| 1 Day vs. 2 Days | 0.005767 | 0.012534 | 0.016686 | 0.019197 |

| 3 Days vs. 7 Days | 0.040404 | 0.049662 | 0.042725 | 0.171368 |

| 7 Days vs. 4 Weeks | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 |

| STH | Mansonellosis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self | Family Member | Self | Family Member | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Without prior diagnosis of contamination | 232 | 72.5 | 229 | 71.6 | Without prior diagnosis of contamination | 231 | 72.2 | 225 | 70.3 |

| Probability ≥ 50% of contamination | 261 | 81.6 | 258 | 80.6 | Probability ≥ 50% of contamination | 254 | 79.4 | 248 | 77.8 |

| 100% of contamination | 315 | 98.4 | 314 | 98.1 | 100% of contamination | 311 | 97.1 | 308 | 96.2 |

| STH | Mansonellosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infection Status | p-Value | p-Value (Family Member) | p-Value | p-Value (Family Member) |

| 100% vs. 50% | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 | 0.00001 |

| 50% vs. unknown | 0.006425 | 0.007195 | 0.033823 | 0.038426 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suwa, U.F.; Simão, C.L.G.; Barbosa, U.C.; Sousa, P.M.; Araújo, C.P.M.d.; Martins, M.; Crainey, J.L. High Levels of Community Support for Mansonellosis Interventions in an Endemic Area of the Brazilian Amazon. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10070186

Suwa UF, Simão CLG, Barbosa UC, Sousa PM, Araújo CPMd, Martins M, Crainey JL. High Levels of Community Support for Mansonellosis Interventions in an Endemic Area of the Brazilian Amazon. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2025; 10(7):186. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10070186

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuwa, Uziel Ferreira, Carla Letícia Gomes Simão, Ulysses Carvalho Barbosa, Patrícia Moura Sousa, Cláudia Patrícia Mendes de Araújo, Marilaine Martins, and James Lee Crainey. 2025. "High Levels of Community Support for Mansonellosis Interventions in an Endemic Area of the Brazilian Amazon" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 10, no. 7: 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10070186

APA StyleSuwa, U. F., Simão, C. L. G., Barbosa, U. C., Sousa, P. M., Araújo, C. P. M. d., Martins, M., & Crainey, J. L. (2025). High Levels of Community Support for Mansonellosis Interventions in an Endemic Area of the Brazilian Amazon. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 10(7), 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10070186