Genetic Characterization and Zoonotic Potential of Leptospira interrogans Identified in Small Non-Flying Mammals from Southeastern Atlantic Forest, Brazil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

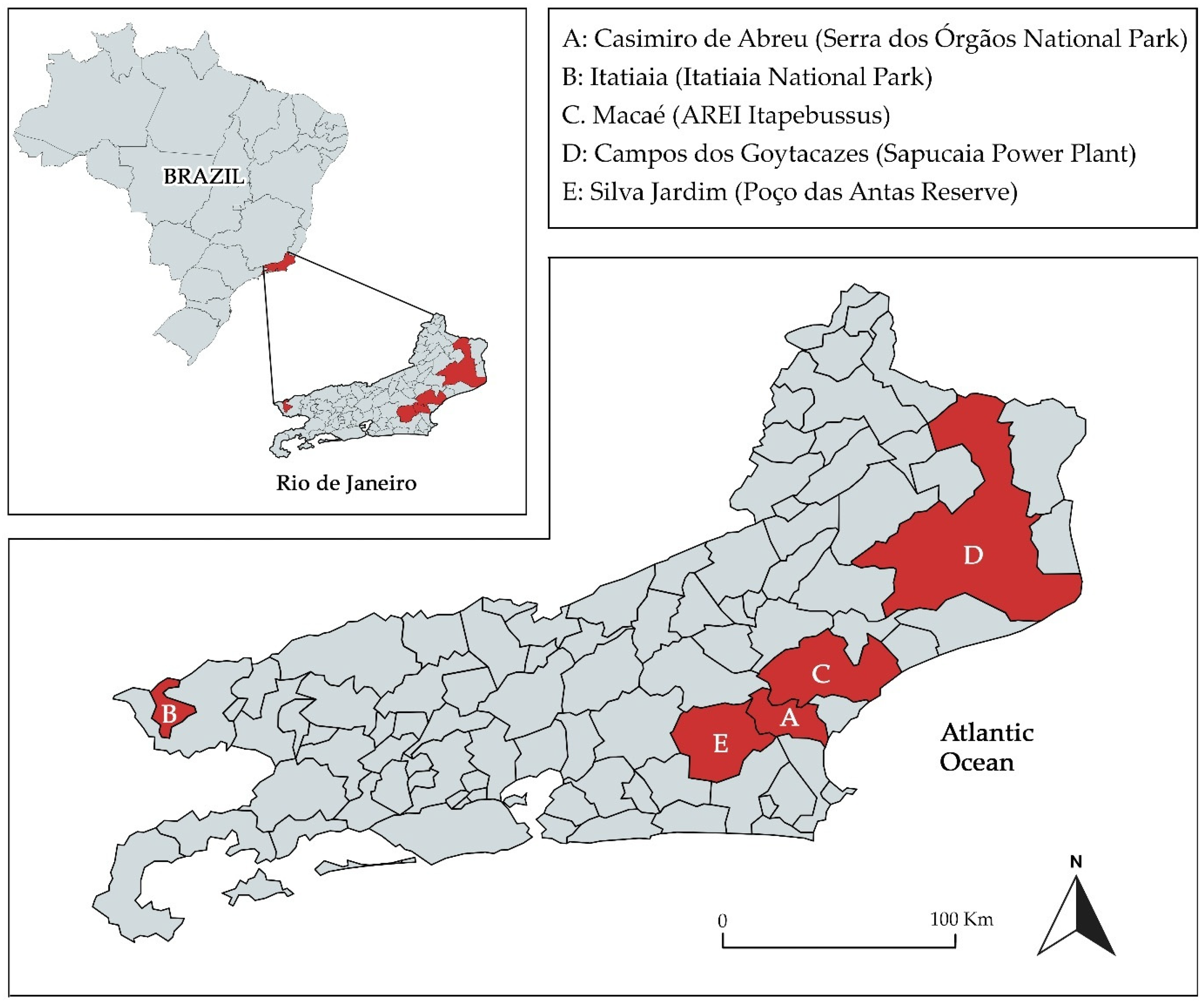

2.1. Animal Capture and Study Areas

2.2. Molecular Diagnosis

2.3. Genetic Characterization of Pathogenic Leptospira spp.

2.4. Phylogenetic Analyses

2.5. Assessment of Genetic Diversity and Determination of Haplotype Circulation Patterns

3. Results

3.1. Molecular Identification of Pathogenic Leptospira spp.

3.2. Genetic Characterization of Pathogenic Leptospira spp. Identified

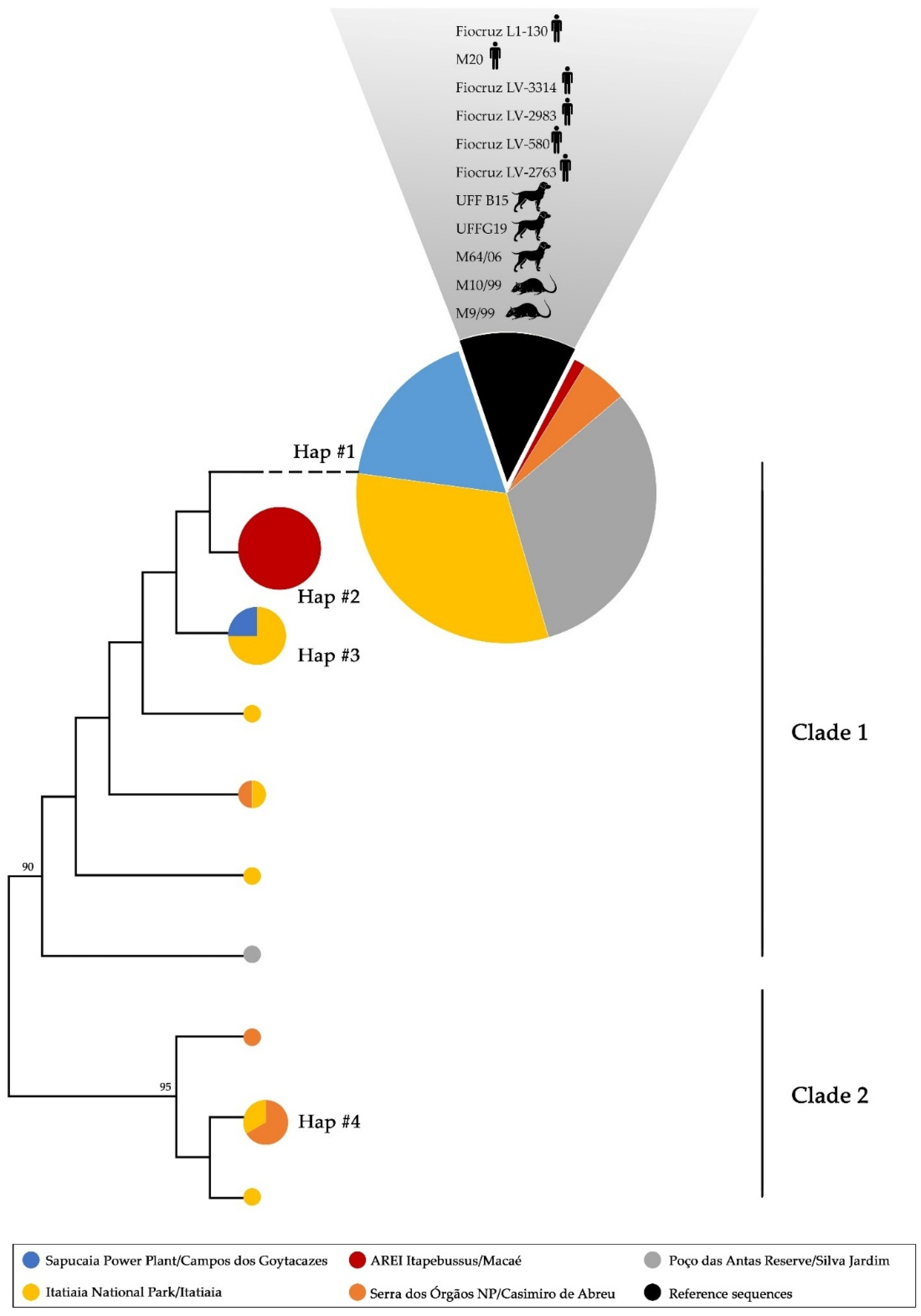

3.3. Phylogenetic Analyses and Haplotype Distribution

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karpagam, K.B.; Ganesh, B. Leptospirosis: A neglected tropical zoonotic infection of public health importance—An updated review. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barragan, V.; Olivas, S.; Keim, P.; Pearson, T. Critical knowledge gaps in our understanding of environmental cycling and transmission of Leptospira spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e01190-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.S.; Matthias, M.A.; Vinetz, J.M.; Fouts, D.E. Leptospiral pathogenomics. Pathogens 2014, 3, 280–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putz, E.J.; Nally, J.E. Investigating the immunological and biological equilibrium of reservoir hosts and pathogenic Leptospira: Balancing the solution to an acute problem? Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, B.; de la Peña Moctezuma, A. Leptospira and leptospirosis. Vet. Microbiol. 2010, 140, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze, M.H.; Raschel, H.; Langen, H.-J.; Stich, A.; Tappe, D. Severe Leptospira interrogans serovar Icterohaemorrhagiae infection with hepato-renal-pulmonary involvement treated with corticosteroids. Clin. Case Rep. 2014, 2, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Dunn, N. Leptospirosis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Haake, D.A.; Levett, P.N. Leptospirosis in humans. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015, 387, 65–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leptospirosis|CDC Yellow Book. 2024. Available online: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2024/infections-diseases/leptospirosis (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Soni, N.; Eyre, M.T.; Souza, F.N.; Diggle, P.J.; Ko, A.I.; Begon, M.; Pickup, R.; Childs, J.E.; Khalil, H.; Carvalho-Pereira, T.S.A.; et al. Disentangling the influence of reservoir abundance and pathogen shedding on zoonotic spillover of the Leptospira agent in urban informal settlements. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1447592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, A.F.; Joly, C.A. Brazilian Atlantic Forest lato sensu: The most ancient Brazilian forest, and a biodiversity hotspot, is highly threatened by climate change. Braz. J. Biol. 2010, 70, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, L.; Loureiro, A.P.; Lilenbaum, W. Effects of rainfall on incidental and host-maintained leptospiral infections in cattle in a tropical region. Vet. J. 2017, 220, 63–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBGE-Censo Brasileiro de 2022. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/trabalho/22827-censo-demografico-2022.html (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Galan, D.I.; Roess, A.A.; Pereira, S.V.C.; Schneider, M.C. Epidemiology of human leptospirosis in urban and rural areas of Brazil, 2000–2015. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baquero, O.S.; Machado, G. Spatiotemporal dynamics and risk factors for human leptospirosis in Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santa Rosa, C.A.; Sulzer, C.R.; Giorgi, W.; da Silva, A.S.; Yanaguita, R.M.; Lobao, A.O. Leptospirosis in wildlife in Brazil: Isolation of a new serotype in the Pyrogenes group. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1975, 36, 1363–1365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cordeiro, F.; Sulzer, C.R.; Ramos, A.A. Leptospira interrogans in several wildlife species in Southeast Brazil. Rev. Bras. Pesq. Vet. 1981, 1, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Medici, E.P.; Mangini, P.R.; Fernandes-Santos, R.C. Health assessment of wild Lowland Tapir (Tapirus terrestris) populations in the Atlantic Forest and Pantanal biomes, Brazil (1996–2012). J. Wildl. Dis. 2014, 50, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornazari, F.; Langoni, H.; Marson, P.M.; Nóbrega, D.B.; Teixeira, C.R. Leptospira reservoirs among wildlife in Brazil: Beyond rodents. Acta Trop. 2018, 178, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libonati, H.; Pinto, P.S.; Lilenbaum, W. Seronegativity of bovines face to their own recovered leptospiral isolates. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 108, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.S.; Di Azevedo, M.I.N.; D’Andrea, P.S.; do Val Vilela, R.; Lilenbaum, W. Neotropical wild rodents Akodon and Oligoryzomys (Cricetidae: Sigmodontinae) as important carriers of pathogenic renal Leptospira in the Atlantic Forest, in Brazil. Res. Vet. Sci. 2019, 124, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.S.; D’Andrea, P.S.; Vilela, R.d.V.; Loretto, D.; Jaeger, L.H.; Carvalho-Costa, F.A.; Lilenbaum, W. Pathogenic Leptospira species are widely disseminated among small mammals in Atlantic Forest Biome. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 1195–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamond, C.; Martins, G.; Loureiro, A.P.; Pestana, C.; Lawson-Ferreira, R.; Medeiros, M.A.; Lilenbaum, W. Urinary PCR as an increasingly useful tool for an accurate diagnosis of leptospirosis in livestock. Vet. Res. Commun. 2014, 38, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.-Y.; Low, G.K.-K.; Chee, H.-Y. Diagnostic accuracy of genetic markers and nucleic acid techniques for the detection of Leptospira in clinical samples: A meta-analysis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillová, L.; Angermeier, H.; Levy, M.; Giard, M.; Lastère, S.; Picardeau, M. Circulating genotypes of Leptospira in French Polynesia: An 9-Year molecular epidemiology surveillance follow-up study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, M.A.; Blackshields, G.; Brown, N.P.; Chenna, R.; McGettigan, P.A.; McWilliam, H.; Valentin, F.; Wallace, I.M.; Wilm, A.; Lopez, R.; et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2947–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X.; Xie, Z. DAMBE: Software package for data analysis in molecular biology and evolution. J. Hered. 2001, 92, 371–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh, J.W.; Bryant, D. Monte Carlo strategies for selecting parameter values in simulation experiments. Syst. Biol. 2015, 64, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, E.C.; Fornazari, F.; de Paula Antunes, J.M.A.; de Castro Demoner, L.; de Oliveira, L.H.O.; Peres, M.G.; Megid, J.; Langoni, H. Molecular detection of Leptospira spp. in small wild rodents from rural areas of São Paulo State, Brazil. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2023, 56, e0160-2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, E.A.; Lockaby, G. Leptospirosis and the environment: A review and future directions. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, L.D.S.; Braga Domingos, S.C.; di Azevedo, M.I.N.; Peruquetti, R.C.; de Albuquerque, N.F.; D’Andrea, P.S.; Botelho, A.L.d.M.; Crisóstomo, C.F.; Vieira, A.S.; Martins, G.; et al. Small mammals as carriers/hosts of Leptospira spp. in the Western Amazon Forest. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 569004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, V.C.; Gamietea, I.; Loffler, S.G.; Brihuega, B.F.; Beldomenico, P.M. New host species for Leptospira borgpetersenii and Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni. Vet. Microbiol. 2018, 215, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, J.E.B.; Knobel, D.L.; Allan, K.J.; Bronsvoort, B.M.d.C.; Handel, I.; Agwanda, B.; Cutler, S.J.; Olack, B.; Ahmed, A.; Hartskeerl, R.A.; et al. Urban leptospirosis in Africa: A cross-sectional survey of Leptospira infection in rodents in the Kibera Urban Settlement, Nairobi, Kenya. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013, 89, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benavidez, K.M.; Guerra, T.; Torres, M.; Rodriguez, D.; Veech, J.A.; Hahn, D.; Miller, R.J.; Soltero, F.V.; Ramírez, A.E.P.; Perez de León, A.; et al. The prevalence of Leptospira among invasive small mammals on Puerto Rican cattle farms. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, F.; Ribeiro, G.S.; Felzemburgh, R.D.M.; Santos, N.; Reis, R.B.; Santos, A.C.; Fraga, D.B.M.; Araujo, W.N.; Santana, C.; Childs, J.E.; et al. Influence of household rat infestation on Leptospira transmission in the urban slum environment. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorge, S.; Hartleben, C.P.; Seixas, F.K.; Coimbra, M.A.A.; Stark, C.B.; Larrondo, A.G.; Amaral, M.G.; Albano, A.P.N.; Minello, L.F.; Dellagostin, O.A.; et al. Leptospira borgpetersenii from free-living white-eared opossum (Didelphis albiventris): First isolation in Brazil. Acta Trop. 2012, 124, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulsenheimer, B.C.; Tonin, A.A.; von Laer, A.E.; Dos Santos, H.F.; Sangioni, L.A.; Fighera, R.; Dos Santos, M.Y.; Brayer, D.I.; de Avila Botton, S. Leptospira borgptersenii and Leptospira interrogans identified in wild mammals in Rio Grande Do Sul, Brazil. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 1941–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chang, Y.-F.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhuang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, L.; et al. Whole genome sequencing revealed host adaptation-focused genomic plasticity of pathogenic Leptospira. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croix, M.D.S.; Holmes, J.; Wanford, J.J.; Moxon, E.R.; Oggioni, M.R.; Bayliss, C.D. Selective and non-selective bottlenecks as drivers of the evolution of hypermutable bacterial loci. Mol. Microbiol. 2020, 113, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wein, T.; Dagan, T. The effect of population bottleneck size and selective regime on genetic diversity and evolvability in bacteria. Genome Biol. Evol. 2019, 11, 3283–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, L.H.; Pestana, C.P.; Carvalho-Costa, F.A.; Medeiros, M.A.; Lilenbaum, W. Characterization of the clonal subpopulation Fiocruz L1–130 of Leptospira interrogans in rats and dogs from Brazil. J. Med. Microbiol. 2018, 67, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Azevedo, M.I.N.; Aymée, L.; Borges, A.L.D.S.B.; Lilenbaum, W. Molecular epidemiology of pathogenic Leptospira spp. infecting dogs in Latin America. Animals 2023, 13, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, F.H.; Sanchez, A.; Aidar, M.P.M.; Rochelle, A.L.C.; Tarabalka, Y.; Fonseca, M.G.; Phillips, O.L.; Gloor, E.; Aragão, L.E.O.C. Mapping Atlantic Rainforest degradation and regeneration history with indicator species using convolutional network. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guedes Pinto, L.F.; Voivodic, M. Reverse the tipping point of the Atlantic Forest for mitigation. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 364–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfenning-Butterworth, A.; Buckley, L.B.; Drake, J.M.; Farner, J.E.; Farrell, M.J.; Gehman, A.-L.M.; Mordecai, E.A.; Stephens, P.R.; Gittleman, J.L.; Davies, T.J. Interconnecting global threats: Climate change, biodiversity loss, and infectious diseases. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e270–e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Collection Site | Host | Haplogroup | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | #2 | #3 | #4 | ND | ||

| (A) Serra dos Órgãos NP (n = 8) | Didelphis aurita (n = 1) | 1 | ||||

| Akodon montensis (n = 3) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Oligoryzomys nigrips (n = 3) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Trinomys marmosa (n = 1) | 1 | |||||

| (B) Itatiaia NP (n = 34) | Monodelphis sp. (n = 4) | 2 | 2 | |||

| Akodon sp. (n = 8) | 6 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Brucepattersonius sp. (n = 10) | 8 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Delomys sp. (n = 6) | 3 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Oligoryzomys sp. (n = 2) | 2 | |||||

| Oxymycterus sp. (n = 4) | 3 | 1 | ||||

| (C) AREI Itapebussus (n = 10) | Marmosa paraguayana (n = 5) | 1 | 4 | |||

| Akodon cursor (n = 3) | 3 | |||||

| Mus musculus (n = 2) | 2 | |||||

| (D) Sapucaia Power Plant * (n = 15) | Mus musculus (n = 15) | 14 | 1 | |||

| (E) Poço das Antas Reserve * (n = 26) | Akodon sp. (n = 9) | 9 | ||||

| Mus musculus (n = 4) | 4 | |||||

| Necromys lasiurus (n = 13) | 12 | 1 | ||||

| Total | 68 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 7 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Azevedo, M.I.N.; Soares, A.C.d.R.; Ezepha, C.; Carvalho-Costa, F.A.; Vieira, A.S.; Lilenbaum, W. Genetic Characterization and Zoonotic Potential of Leptospira interrogans Identified in Small Non-Flying Mammals from Southeastern Atlantic Forest, Brazil. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10030062

Di Azevedo MIN, Soares ACdR, Ezepha C, Carvalho-Costa FA, Vieira AS, Lilenbaum W. Genetic Characterization and Zoonotic Potential of Leptospira interrogans Identified in Small Non-Flying Mammals from Southeastern Atlantic Forest, Brazil. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2025; 10(3):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10030062

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Azevedo, Maria Isabel Nogueira, Ana Clara dos Reis Soares, Camila Ezepha, Filipe Anibal Carvalho-Costa, Anahi Souto Vieira, and Walter Lilenbaum. 2025. "Genetic Characterization and Zoonotic Potential of Leptospira interrogans Identified in Small Non-Flying Mammals from Southeastern Atlantic Forest, Brazil" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 10, no. 3: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10030062

APA StyleDi Azevedo, M. I. N., Soares, A. C. d. R., Ezepha, C., Carvalho-Costa, F. A., Vieira, A. S., & Lilenbaum, W. (2025). Genetic Characterization and Zoonotic Potential of Leptospira interrogans Identified in Small Non-Flying Mammals from Southeastern Atlantic Forest, Brazil. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 10(3), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10030062