Impact of Wuchereria bancrofti Infection on Cervical Mucosal Immunity and Human Papillomavirus Prevalence in Women from Lindi and Mbeya Regions, Tanzania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Volunteers and Baseline Tests

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Flow Cytometry

2.4. Human Papillomavirus DNA Detection and Genotyping

2.5. Histopathology of Papanicolaou Smear

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

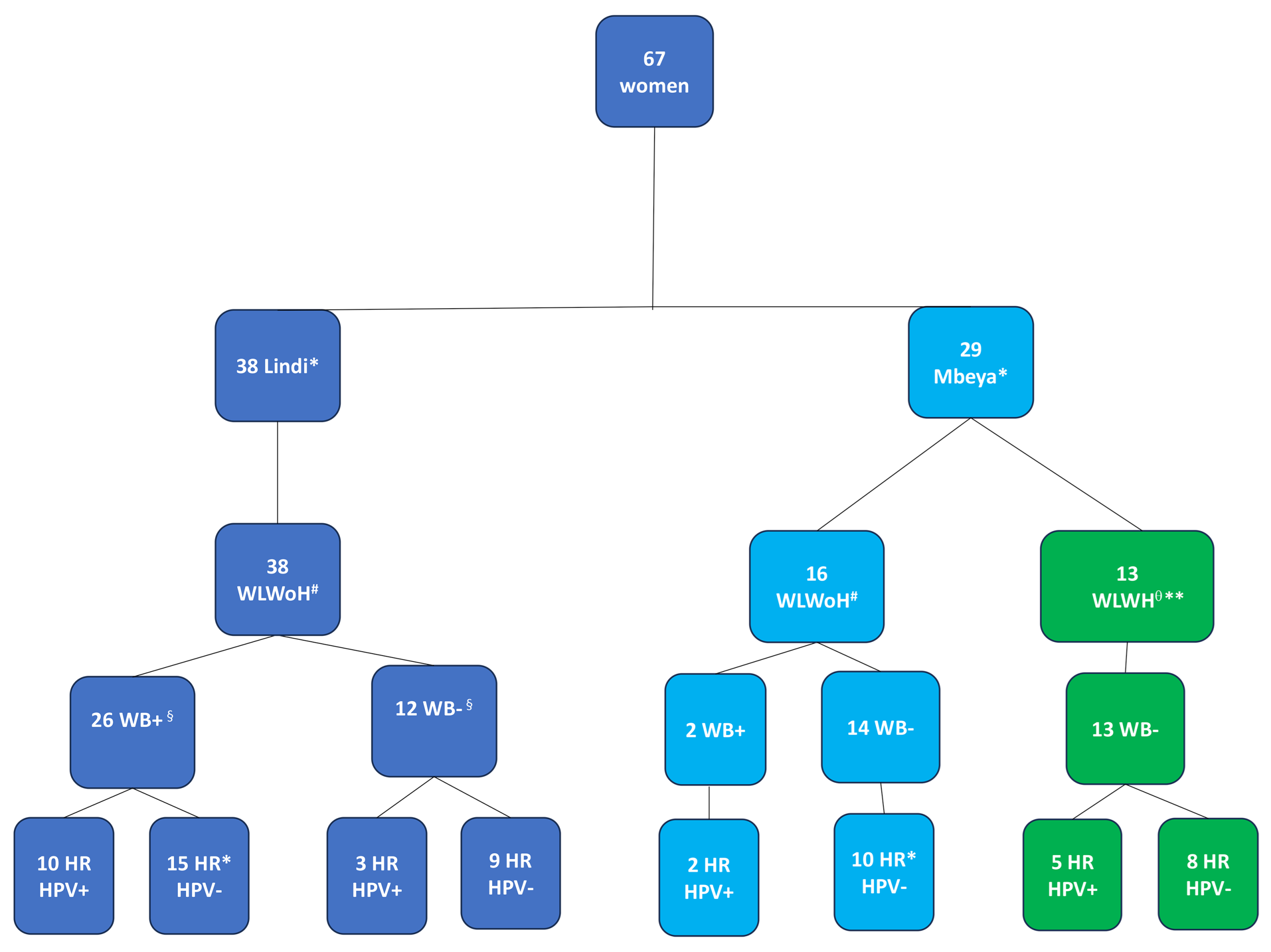

3.1. Study Cohort

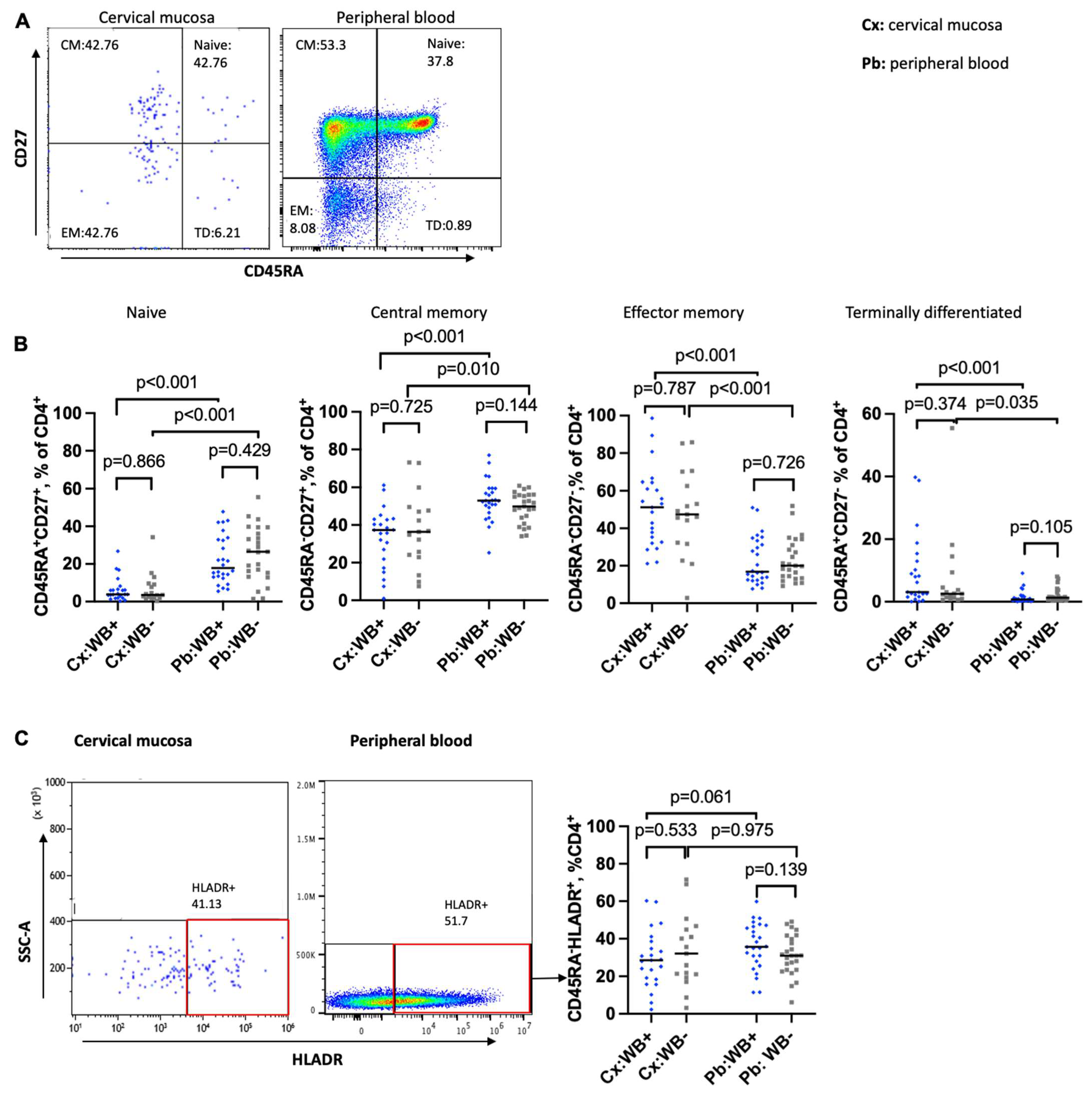

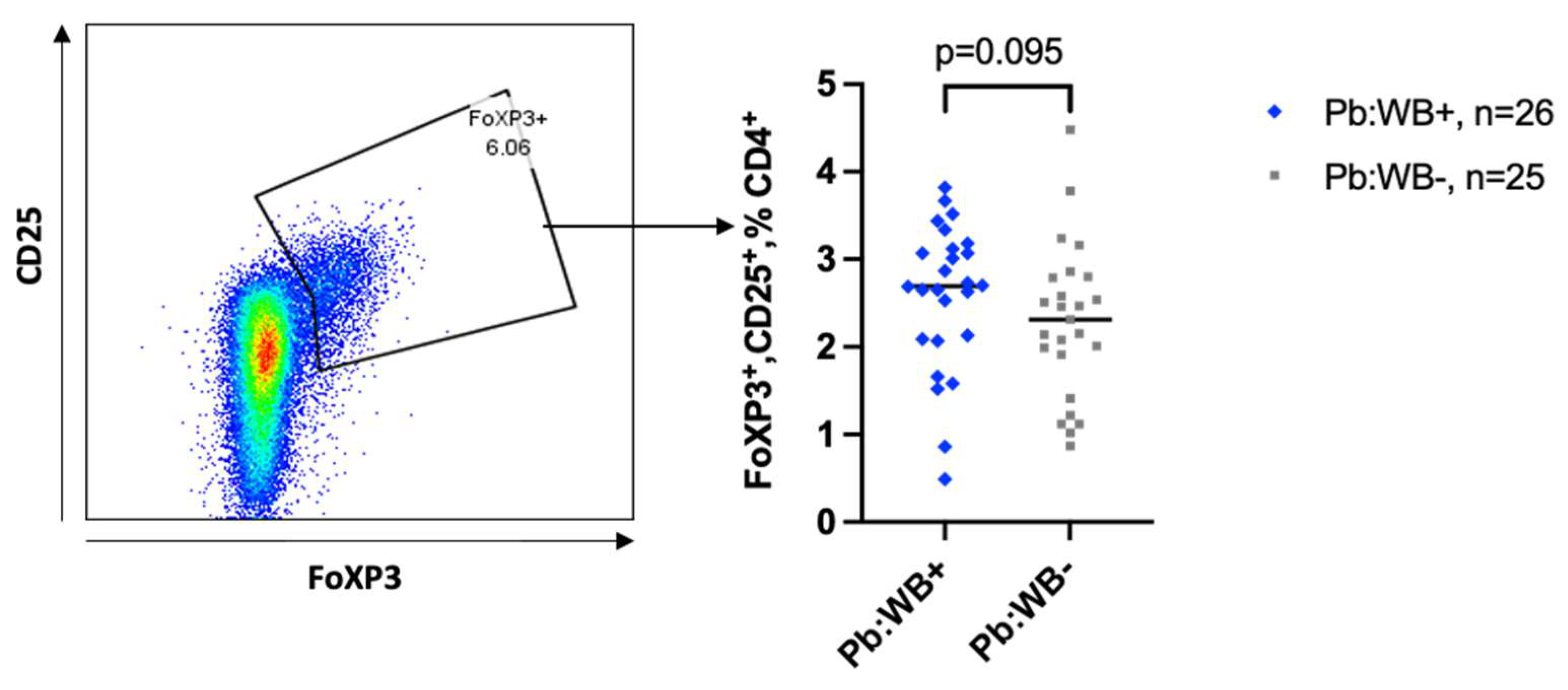

3.2. Impact of WB on the Maturation Status of CD4 T Cells in the Cervical Mucosa and Peripheral Blood

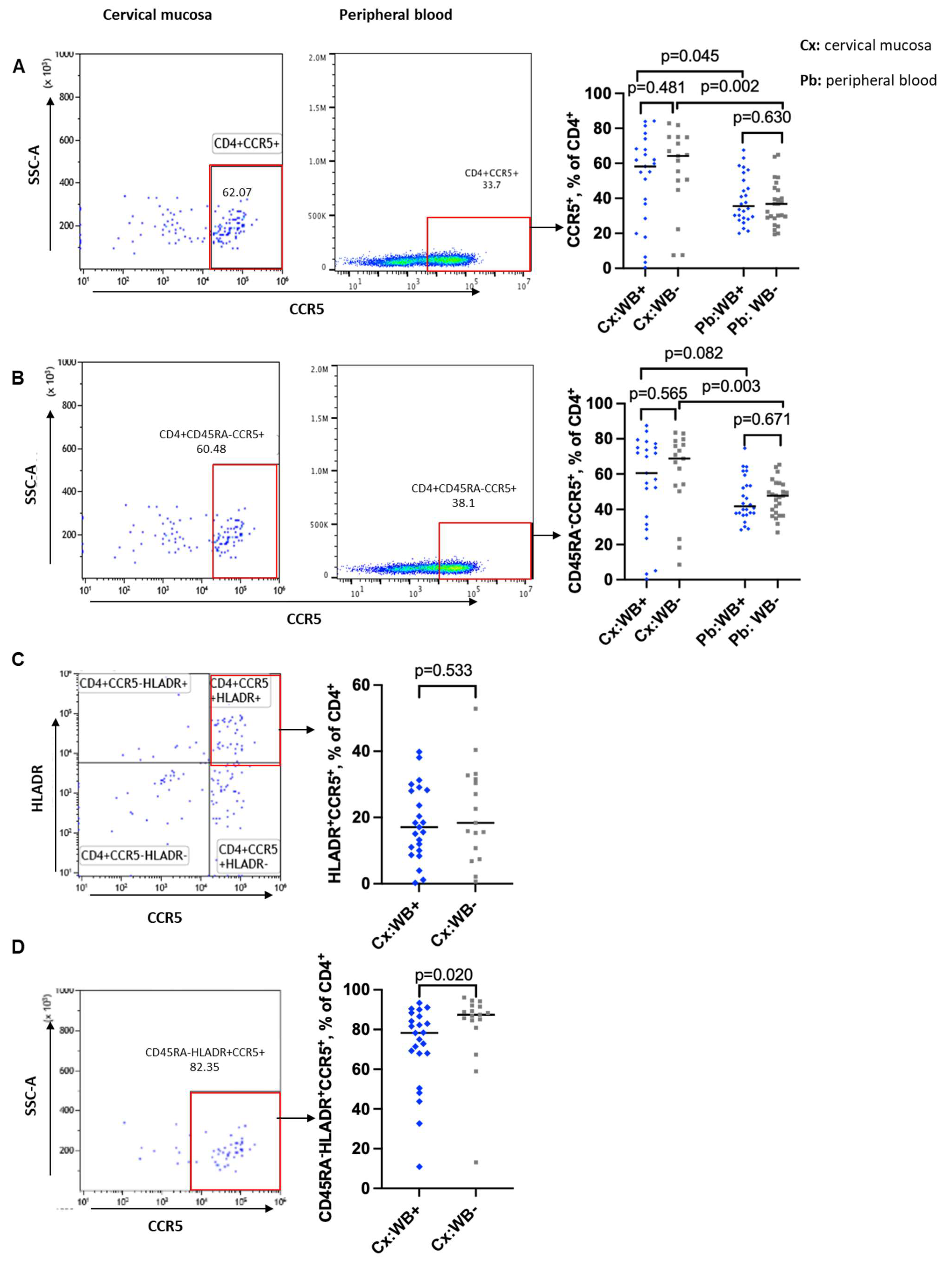

3.3. Influence of WB Infection Status on CD4 T Cells Expression of CCR5 and a4b7

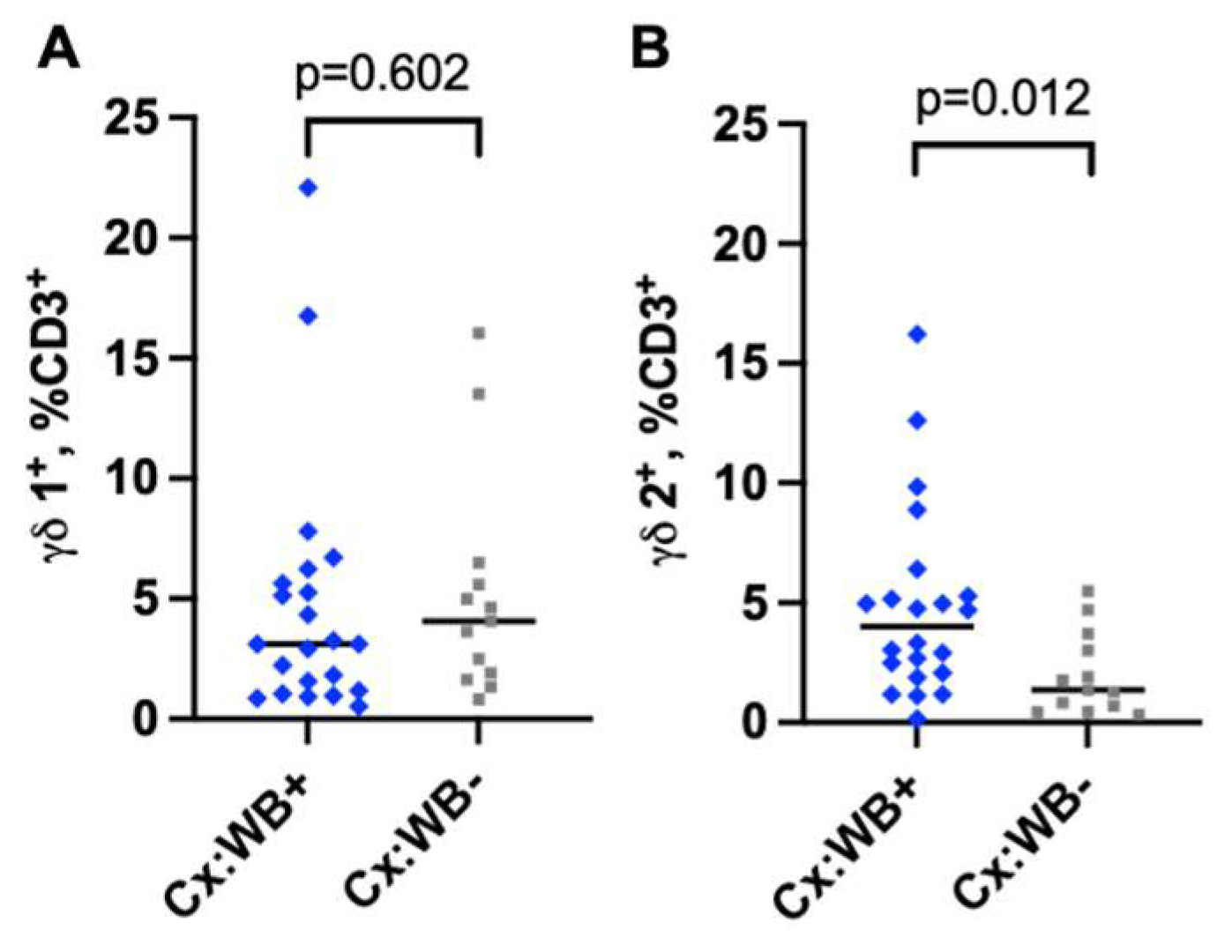

3.4. Infection with WB Increases the Frequency of γδ2 CD3 T Cells in the Cervical Mucosa

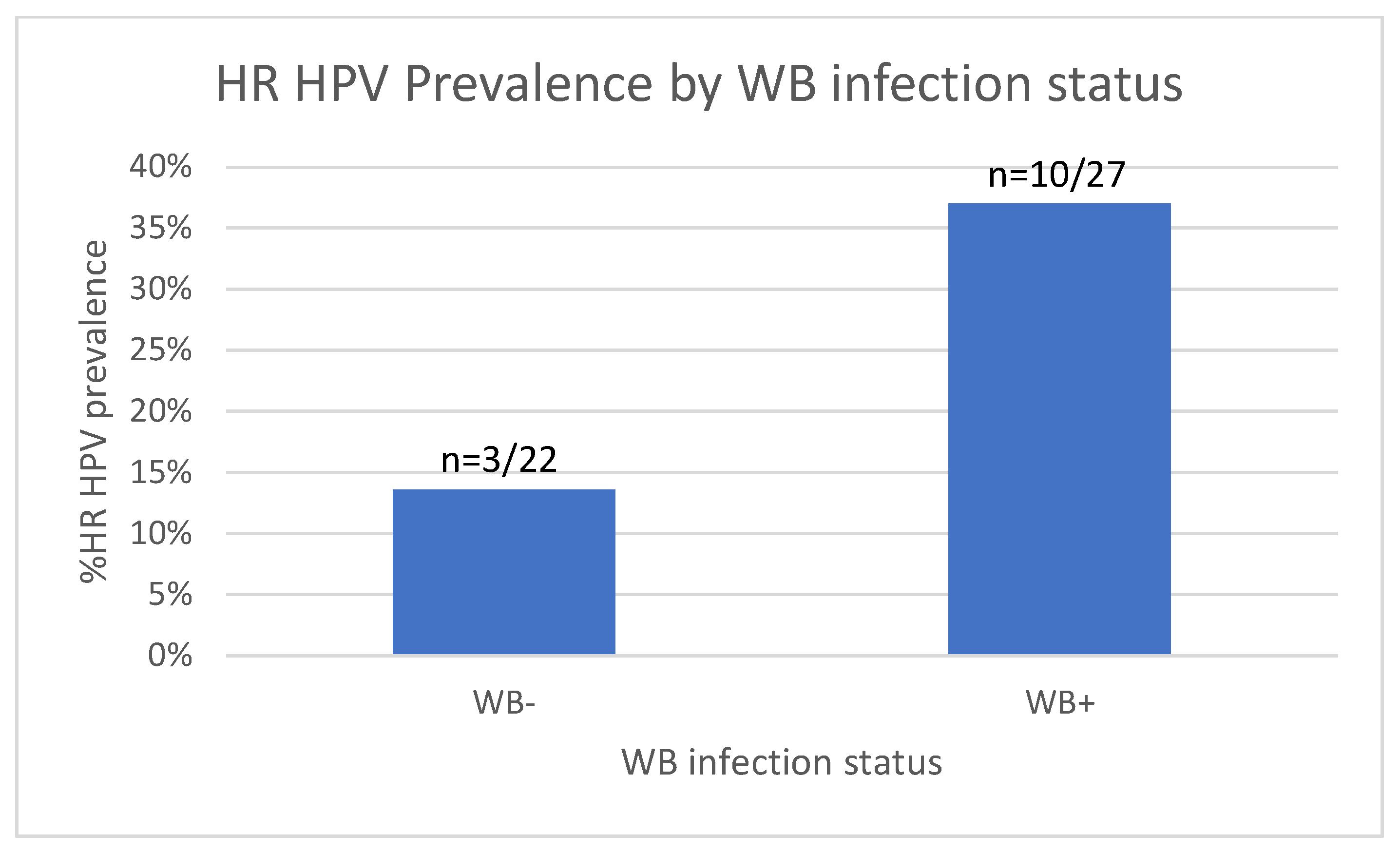

3.5. Increased HR HPV Prevalence in WB-Infected Women

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Cx | Cervical mucosa |

| FRT | Female reproductive tract |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| HR HPV | High-Risk Human Papillomavirus |

| Pb | Peripheral blood |

| STI | Sexually transmitted infection |

| WB+ | Wuchereria Bancroft-infected |

| WB− | Wuchereria bancrofti-uninfected |

| WLWH | Women living with HIV |

| WLWoH | Women living without HIV |

References

- Albuquerque, C.M.; Cavalcanti, V.M.; Melo, M.V.A.; Verçosa, P.; Regis, L.N.; Hurd, M. Bloodmeal Microfilariae Density and the Uptake and Establishment of Wuchereria bancrofti Infections in Culex quinquefasciatus and Aedes aegypti. Memórias Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 1999, 94, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appawu, M.A.; Dadzie, S.K.; Baffoe-Wilmot, A.; Wilson, M.D. Lymphatic filariasis in Ghana: Entomological investigation of transmission dynamics and intensity in communities served by irrigation systems in the Upper East Region of Ghana. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2001, 6, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derua, Y.A.; Rumisha, S.F.; Batengana, B.M.; Max, D.A.; Stanley, G.; Kisinza, W.N.; Mboera, L.E.G. Lymphatic filariasis transmission on Mafia Islands, Tanzania: Evidence from xenomonitoring in mosquito vectors. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, S.M.; Fischer, K.; Weil, G.J.; Christensen, B.M.; Fischer, P.U. Distribution of Brugia malayi larvae and DNA in vector and non-vector mosquitoes: Implications for molecular diagnostics. Parasit. Vectors 2009, 2, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maizels, R.M.; Partono, F.; Oemijatit, S.; Ogilviet, B.M. Antigenic analysis of Brugia timori, a filarial nematode of man: Initial characterization by surface radioiodination and evaluation of diagnostic potential. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1983, 51, 269–277. [Google Scholar]

- Ughasi, J.; Bekard, H.E.; Coulibaly, M.; Adabie-Gomez, D.; Gyapong, J.; Appawu, M.; Wilson, M.D.; Boakye, D.A. Mansonia africana and Mansonia uniformis are Vectors in the transmission of Wuchereria bancrofti lymphatic filariasis in Ghana. Parasit. Vectors 2012, 5, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromwell, E.; Schmidt, C.; Kwong, K.; Piggot, D.; Mupfasoni, D.; Biswas, G. The global distribution of lymphatic filariasis, 2000–18: A geospatial analysis. Lancet 2020, 8, e1186–e1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neglected Tropical Diseases Control Programme. Lymphatic Filariasis; NTDCP: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2018; Available online: https://www.ntdcp.go.tz/about/about_program (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Kroidl, I.; Saathoff, E.; Maganga, L.; Makunde, W.H.; Hoerauf, A.; Geldmacher, C.; Clowes, P.; Maboko, L.; Hoelscher, M. Effect of Wuchereria bancrofti infection on HIV incidence in southwest Tanzania: A prospective cohort study. Lancet 2016, 388, 1912–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnkai, J.; Marandu, T.F.; Mhidze, J.; Urio, A.; Maganga, L.; Haule, A.; Kavishe, G.; Ntapara, E.; Chiwerengo, N.; Clowes, P.; et al. Step towards elimination of Wuchereria bancrofti in Southwest Tanzania 10 years after mass drug administration with Albendazole and Ivermectin. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, W.; Mushi, V.; Tarimo, D.; Mwingira, U. Prevalence and management of filarial lymphoedema and its associated factors in Lindi district, Tanzania: A community-based cross-sectional study. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2022, 27, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaxter, M.L.; Maizels, R.M. Nematode Surface Coats: Actively Evading Immunity. Parasitol. Today 1992, 8, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C.L.; Mahanty, S.; Kumaraswami, V.; Abrams, J.S.; Regunathan, J.; Jayaraman, K.; Ottesen, E.A.; Nutman, T.B. Cytokine Control of Parasite-specific Anergy in Human Lymphatic Filariasis. Preferential Induction of a Regulatory T Helper Type 2 Lymphocyte Subset. J. Clin. Invest. 1993, 92, 1667–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartono, E.; Kruize, Y.C.M.; Kurniawan, A.; Maizels, R.; Yazdanbakhsh, M. Depression of antigen-specific interleukin-5 and interferon-gamma responses in human lymphatic filariasis as a function of clinical status and age. J. Infect. Dis. 1997, 175, 1276–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.; Clark, C.E.; Lugli, E.; Roederer, M.; Nutman, T.B. Filarial Infection Modulates the Immune Response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis through Expansion of CD4+ IL-4 Memory T Cells. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 2706–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degarege, A.; Legesse, M.; Medhin, G.; Animut, A.; Erko, B. Malaria and Related Outcomes in Patients with Intestinal Helminths: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacher, M.; Singhasivanon, P.; Yimsamran, S.; Thanyavanich, N.; Wuthisen, P.; Looareesuwan, S. Intestinal helminth infections are associated with increased incidence of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Thailand. J. Parasitol. 2002, 88, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinkovich, A.; Weisman, Z.; Greenberg, Z.; Nahmias, J.; Eitan, S.; Stein, M.; Bentwich, Z. Decreased CD4 and increased CD8 counts with T cell activation is associated with chronic helminth infection. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1998, 114, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinkovich, A.; Borkow, G.; Weisman, Z.; Tsimanis, A.; Stein, M.; Bentwich, Z. Increased CCR5 and CXCR4 expression in Ethiopians living in Israel: Environmental and constitutive factors. Clin. Immunol. 2001, 100, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chachage, M.; Podola, L.; Clowes, P.; Nsojo, A.; Bauer, A.; Mgaya, O.; Kowour, D.; Froeschl, G.; Maboko, L.; Hoelscher, E.; et al. Helminth-Associated Systemic Immune Activation and HIV Co-receptor Expression: Response to Albendazole/Praziquantel Treatment. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secor, W.E.; Shah, A.; Mwinzi, P.M.N.; Ndenga, B.A.; Watta, C.O.; Karanja, D.M.S. Increased Density of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Coreceptors CCR5 and CXCR4 on the Surfaces of CD4+ T Cells and Monocytes of Patients with Schistosoma mansoni Infection. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 6668–6671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroidl, I.; Marandu, T.F.; Maganga, L.; Horn, S.; Urio, A.; Haule, A.; Mhidze, J.; Mnkai, J.; Mosoba, M.; Ntapara, E.; et al. Articles Impact of Quasielimination of Wuchereria bancrofti on HIV Incidence in Southwest Tanzania: A 12-year Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet HIV 2025, 12, e338–e345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicala, C.; Martinelli, E.; Mcnally, J.P.; Goode, D.J.; Gopaul, R.; Hiatt, J.; Jelicic, K.; Kottilil, S.; Macleod, K.; O’shea, A.; et al. The Integrin alpha4beta7 Forms a Complex with Cell-Surface CD4 and Defines a T-cell Subset That is Highly Susceptible to Infection by HIV-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20877–20882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatjana, D.; Virginia, L.; Graham, P.; Scott, R.; Kirsten, N.; Charmagne, C.; Paul, J.; Richard, A.; John, P.; William, A. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature 1996, 381, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndts, K.; Deininger, S.; Specht, S.; Klarmann, U.; Mand, S.; Adjobimey, T.; Debrah, A.Y.; Batsa, L.; Kwarteng, A.; Epp, C.; et al. Elevated adaptive immune responses are associated with latent infections of Wuchereria bancrofti. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 6, e1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, S.; Borrero-Wolff, D.; Ritter, M.; Arndts, K.; Wiszniewsky, A.; Debrah, L.B.; Debrah, A.Y.; Osei-Mensah, J.; Chachage, M.; Hoerauf, A.; et al. Distinct Immune Profiles of Exhausted Effector and Memory CD8+ T Cells in Individuals With Filarial Lymphedema. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 680832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, S.; Ritter, M.; Arndts, K.; Borrero-Wolff, D.; Wiszniewsky, A.; Debrah, L.B.; Debrah, A.Y.; Osei-Mensah, J.; Chachage, M.; Hoerauf, A.; et al. Filarial Lymphedema Patients Are Characterized by Exhausted CD4+ T Cells. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 11, 767306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroidl, I.; Chachage, M.; Mnkai, J.; Nsojo, A.; Berninghoff, M.; Verweij, J.J.; Maganga, L.; Ntinginya, N.E.; Maboko, L.; Clowes, P.; et al. Wuchereria bancrofti infection is linked to systemic activation of CD4 and CD8 T cells. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahamani, A.A.; Horn, S.; Ritter, M.; Feichtner, A.; Osei-Mensah, J.; Opoku, V.S.; Debrah, L.B.; Marandu, T.F.; Haule, A.; Mhidze, J.; et al. Stage-Dependent Increase of Systemic Immune Activation and CCR5+CD4+ T Cells in Filarial Driven Lymphedema in Ghana and Tanzania. Pathogens 2023, 12, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, M.; Osei-Mensah, J.; Debrah, L.B.; Kwarteng, A.; Mubarik, Y.; Debrah, A.Y.; Pfarr, K.; Hoerauf, A.; Layland, L.E. Wuchereria bancrofti-infected individuals harbor distinct IL-10-producing regulatory B and T cell subsets which are affected by antifilarial treatment. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, Y.; Morrison, C.S.; Chen, P.L.; Gao, X.; Yamamoto, H.; Chipato, T.; Anderson, S.; Barbieri, R.; Salata, R.; Doncel, G.F.; et al. Cervical and systemic innate immunity predictors of HIV risk linked to genital herpes acquisition and time from HSV-2 seroconversion. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2023, 99, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joag, V.R.; McKinnon, L.R.; Liu, J.; Kidane, S.T.; Yudin, M.H.; Nyanga, B.; Kimwaki, S.; Besel, K.E.; Obila, J.O.; Huibner, S.; et al. Identification of preferential CD4+ T-cell targets for HIV infection in the cervix. Mucosal Immunol. 2016, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbuya, W.; McHaro, R.; Mhizde, J.; Mnkai, J.; Mahenge, A.; Mwakatima, M.; Mwalongo, W.; Chiwerengo, N.; Hölscher, M.; Lennemann, T.; et al. Depletion and activation of mucosal CD4 T cells in HIV infected women with HPV-associated lesions of the cervix uteri. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omondi, M.A.; Kamassa, E.H.; Katawa, G.; Tchopba, C.N.; Vogelbusch, C.; Parcina, M.; Tchadié, E.P.; Amessoudji, O.M.; Arndts, K.; Karou, S.D.; et al. Hookworm infection associates with a vaginal Type 1/Type 2 immune signature and increased HPV load. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1009968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturt, A.S.; Webb, E.L.; Phiri, C.R.; Mudenda, M.; Mapani, J.; Kosloff, B.; Cheeba, M.; Shanaube, K.; Bwalya, J.; Kjetland, E.F.; et al. Female Genital Schistosomiasis and HIV-1 Incidence in Zambian Women: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukair, S.A.; Allen, S.A.; Cianci, G.C.; Stieh, D.J.; Anderson, M.R.; Baig, S.M.; Gioia, C.J.; Spongberg, E.J.; Kauffman, S.M.; McRaven, M.D.; et al. Human cervicovaginal mucus contains an activity that hinders HIV-1 movement. Mucosal Immunol. 2013, 6, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacroix, G.; Gouyer, V.; Gottrand, F.; Desseyn, J.L. The cervicovaginal mucus barrier. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wira, C.R.; Ghosh, M.; Smith, J.M.; Shen, L.; Connor, R.I.; Sundstrom, P.; Frechette, G.M.; Hill, E.T.; Fahey, J.V. Epithelial cell secretions from the human female reproductive tract inhibit sexually transmitted pathogens and Candida albicans but not Lactobacillus. Mucosal Immunol. 2011, 4, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castle, P.E.; Hillier, S.L.; Rabe, L.K.; Hildesheim, A.; Herrero, R.; Bratti, M.C.; Sherman, M.E.; Burk, R.D.; Rodriguez, A.C.; Alfaro, M.; et al. An Association of Cervical Inflammation with High-Grade Cervical Neoplasia in Women Infected with Oncogenic Human Papillomavirus (HPV). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001, 10, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Masson, L.; Mlisana, K.; Little, F.; Werner, L.; Mkhize, N.N.; Ronacher, K.; Gamieldien, H.; Williamson, C.; McKinnon, L.R.; Walzl, G.; et al. Defining genital tract cytokine signatures of sexually transmitted infections and bacterial vaginosis in women at high risk of HIV infection: A cross-sectional study. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2014, 90, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, L.; Passmore, J.A.S.; Liebenberg, L.J.; Werner, L.; Baxter, C.; Arnold, K.B.; Williamson, C.; Little, F.; Mansoor, L.E.; Naranbhai, V.; et al. Genital Inflammation and the Risk of HIV Acquisition in Women. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 61, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wira, C.R.; Rodriguez-Garcia, M.; Patel, M.V. The role of sex hormones in immune protection of the female reproductive tract. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, E.-L.; Rudin, A.; Wassén, L.; Holmgren, J. Distribution of lymphocytes and adhesion molecules in human cervix and vagina. Immunology 1999, 96, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifonova, R.T.; Lieberman, J.; van Baarle, D. Distribution of immune cells in the human cervix and implications for HIV transmission. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2014, 71, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monin, L.; Ushakov, D.S.; Arnesen, H.; Bah, N.; Jandke, A.; Muñoz-Ruiz, M.; Carvalho, J.; Joseph, S.; Almeida, B.C.; Green, M.J.; et al. γδ T cells compose a developmentally regulated intrauterine population and protect against vaginal candidiasis. Mucosal Immunol. 2020, 13, 969–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strbo, N.; Romero, L.; Alcaide, M.; Fischl, M. Isolation and flow cytometric analysis of human endocervical gamma delta T cells. J. Vis. Exp. 2017, 2017, 55038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzieva, A.; Dimitrova, V.; Djerov, L.; Dimitrova, P.; Zapryanova, S.; Hristova, I.; Vangelov, I.; Dimova, T. Early pregnancy human decidua is enriched with activated, fully differentiated and pro-inflammatory gamma/delta T cells with diverse TCR repertoires. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, J.E.; Pearson, J.; Scott, P.; Carding, S.R. The Interaction of γδ T Cells with Activated Macrophages Is a Property of the Vγ1 Subset. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 6488–6494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravitt, P.E.; Marks, M.; Kosek, M.; Huang, C.; Cabrera, L.; Olortegui, M.P.; Medrano, A.M.; Trigoso, D.R.; Qureshi, S.; Bardales, G.S.; et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infections are associated with an increase in human papillomavirus prevalence and a T-helper type 2 cytokine signature in cervical fluids. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 213, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameyapoh, A.H.; Katawa, G.; Ritter, M.; Tchopba, C.N.; Tchadié, P.E.; Arndts, K.; Kamassa, H.E.; Mazou, B.; Amessoudji, O.M.; N’djao, A.; et al. Hookworm Infections and Sociodemographic Factors Associated With Female Reproductive Tract Infections in Rural Areas of the Central Region of Togo. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 738894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Zhang, X.; He, L.L.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Deng, R.; Qiu, B.; Liu, F.; Xiao, H.; Li, Q.; et al. Human papillomavirus infections among women with cervical lesions and cervical cancer in Yueyang, China: A cross-sectional study of 3674 women from 2019 to 2022. Virol. J. 2023, 20, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mchome, B.L.; Kjaer, S.K.; Manongi, R.; Swai, P.; Waldstroem, M.; Iftner, T.; Wu, C.; Mwaiselage, J.; Rasch, V. HPV types, cervical high-grade lesions and risk factors for oncogenic human papillomavirus infection among 3416 Tanzanian women. Sex Transm. Infect. 2021, 97, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chachage, M.; Parikh, A.P.; Mahenge, A.; Bahemana, E.; Mnkai, J.; Mbuya, W.; Mcharo, R.; Maganga, L.; Mwamwaja, J.; Gervas, R.; et al. High-risk human papillomavirus genotype distribution among women living with and at risk for HIV in Africa. AIDS 2023, 37, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pangarkar, M.A. The Bethesda System for reporting cervical cytology. Cytojournal. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yao, D.; Zeng, X.; Kasakovski, D.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Zha, X.; Li, Y.; Xu, L. Age related human T cell subset evolution and senescence. Immun. Ageing 2019, 16, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekere, E.F.; Useh, M.F.; Okoroiwu, H.U.; Mirabeau, T.Y. Cysteine-cysteine chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) profile of HIV-infected subjects attending University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar, Southern Nigeria. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faivre, N.; Verollet, C.; Dumas, F. The chemokine receptor CCR5: Multi-faceted hook for HIV-1. Retrovirology 2024, 21, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.G.; Guo, J.; Wu, Y. Chemokine Receptor CCR5 Antagonist Maraviroc: Medicinal Chemistry and Clinical Applications. Curr. Trop. Med. Chem. 2014, 14, 1504–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, C.M.; McLaren, P.J.; Wachihi, C.; Kimani, J.; Plummer, F.A.; Fowke, K.R. Decreased immune activation in resistance to HIV-1 infection is associated with an elevated frequency of CD4(+)CD25(+)FOXP3(+) Regulatory T Cells. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 199, 1318–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koning, F.A.; Otto, S.A.; Hazenberg, M.D.; Dekker, L.; Prins, M.; Miedema, F.; Schuitemaker, H. Low-Level CD4+ T Cell Activation Is Associated with Low Susceptibility to HIV-1 Infection. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 6117–6122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bégaud, E.; Chartier, L.; Marechal, V.; Ipero, J.; Léal, J.; Versmisse, P.; Breton, G.; Fontanet, A.; Capoulade-Metay, C.; Fleury, H.; et al. Reduced CD4 T cell activation and in vitro susceptibility to HIV-1 infection in exposed uninfected Central Africans. Retrovirology 2006, 3, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapira-Nahor, O.; Kalinkovich, A.; Weisman, Z. Increased susceptibility to HIV-1 infection of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from chronically immune-activated individuals. AIDS 1998, 12, 1731–1733. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chetty, A.; Darby, M.G.; Vornewald, P.M.; Martín-Alonso, M.; Filz, A.; Ritter, M.; McSorley, H.J.; Masson, L.; Smith, K.; Brombacher, M.K.; et al. Il4ra-independent vaginal eosinophil accumulation following helminth infection exacerbates epithelial ulcerative pathology of HSV-2 infection. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 579–593.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Tasker, C.; Lespinasse, P.; Dai, J.; Fitzgerald-Bocarsly, P.; Lu, W.; Heller, D.; Chang, T.L.Y. Integrin α4β7 Expression Increases HIV Susceptibility in Activated Cervical CD4+ T Cells by an HIV Attachment-Independent Mechanism. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2015, 69, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douek, D.C.; Brenchley, J.M.; Betts, M.R.; Ambrozak, D.R.; Hill, B.J.; Okamoto, Y.; Casazza, J.P.; Kuruppu, J.; Kunstmank, K.; Wolinskyk, S.; et al. HIV Preferentially Infects HIV-Specific CD4 T Cells. Nature 2002, 417, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarev, A.; McKinnon, L.R.; Pagliuzza, A.; Sivro, A.; Omole, T.E.; Kroon, E.; Chomchey, N.; Phanuphak, N.; Schuetz, A.; Robb, M.L.; et al. Preferential infection of α4β7+ memory CD4+ T cells during early acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, E735–E743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan, J.L.; Kremsner, P.G.; Deelder, A.M.; Yazdanbakhsh, M. Elevated proliferation and interleukin-4 release from CD4+ cells after chemotherapy in human Schistosoma haematobium infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 1996, 26, 1365–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.D.; LeGoff, L.; Harris, A.; Malone, E.; Allen, J.E.; Maizels, R.M. Removal of Regulatory T Cell Activity Reverses Hyporesponsiveness and Leads to Filarial Parasite Clearance In Vivo. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 4924–4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metenou, S.; Dembele, B.; Konate, S.; Dolo, H.; Coulibaly, S.Y.; Coulibaly, Y.I.; Diallo, A.A.; Soumaoro, L.; Coulibaly, M.E.; Sanogo, D.; et al. At Homeostasis Filarial Infections Have Expanded Adaptive T Regulatory but Not Classical Th2 Cells. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 5375–5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, S.; Blauvelt, C.P.; Kumaraswami, V.; Nutman, T.B. Regulatory Networks Induced by Live Parasites Impair Both Th1 and Th2 Pathways in Patent Lymphatic Filariasis: Implications for Parasite Persistence. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 3248–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrick, D.A.; Schrenzel, M.D.; Mulvania, T.; Hsieh, B.; Ferlin, W.G.; Lepper, H. Differential production of interferon-gamma and interleukin-4 in response to Th1- and Th2- stimulating pathogens by gamma delta T cells in vivo. Nature 1995, 373, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sciammas, R.; Kodukula, P.; Tang, Q.; Hendricks, R.L.; Bluestone, J.A. T Cell Receptor- gamma/delta Cells Protect Mice from Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1-induced Lethal Encephalitis. J. Exp. Med. 1997, 185, 1969–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockhart, E.; Green, A.M.; Flynn, J.L. IL-17 Production Is Dominated by gammadelta T Cells rather than CD4 T Cells during Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 4662–4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junqueira, C.; Polidoro, R.B.; Castro, G.; Absalon, S.; Liang, Z.; Santara, S.S.; Crespo, Â.; Pereira, D.B.; Gazzinelli, R.T.; Dvorin, J.D.; et al. γδ T cells suppress Plasmodium falciparum blood-stage infection by direct killing and phagocytosis. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Wu, Q.; Huang, J.; Yang, B.; Liang, C.; Chi, P.; Wu, C. Tissue Resident Memory γδT Cells in Murine Uterus Expressed High Levels of IL-17 Promoting the Invasion of Trophocytes. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 588227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.; Mann, B.T.; Ryan, P.L.; Bosque, A.; Pennington, D.J.; Hackstein, H.; Soriano-Sarabia, N. Deep characterization of human γδ T cell subsets defines shared and lineage-specific traits. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1148988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, A.; Omondi, M.A.; Butters, C.; Smith, K.A.; Katawa, G.; Ritter, M.; Layland, L.; Horsnell, W. Impact of Helminth Infections on Female Reproductive Health and Associated Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 577516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, P.J.; Yin, C.; Martini, F.; Evans, P.S.; Propp, N.; Poccia, F.; Pauza, C.D. HIV-mediated gammadelta T cell depletion is specific for Vgamma2+ cells expressing the Jgamma1.2 segment. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2003, 19, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | N = 40 | Mean | Coefficient (95% CI) | p Value | Coefficient (95% CI) | p Value |

| Cervix cells | ||||||

| CD4+CCR5+ | ||||||

| WB negative * | 17 | 56.3 | Ref | Ref | ||

| WB positive | 23 | 50.3 | −6.0 (−22.3–10.4) | 0.464 | 0.2 (−16–16.5) | 0.977 |

| CD4+CD45RA-CCR5+ | ||||||

| WB negative * | 17 | 60.5 | Ref | Ref | ||

| WB positive | 23 | 54.3 | −6.2 (−22.8–10.4) | 0.456 | 1.8 (−14.4–17.9) | 0.827 |

| CD4+CCR5+HLA-DR+ | ||||||

| WB negative * | 17 | 21.4 | Ref | Ref | ||

| WB positive | 23 | 18.3 | −3.1 (−11.2–5.1) | 0.452 | −1.8 (−11–7.3) | 0.686 |

| CD4+CD45RA-HLA-DR+CCR5+ | ||||||

| WB negative * | 17 | 81.5 | Ref | Ref | ||

| WB positive | 23 | 71.2 | −10.3 (−23.6–3.0) | 0.127 | −8.7 (−23.2–5.7) | 0.227 |

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | N = 35 | Mean | Coefficient (95% CI) | p Value | Coefficient (95% CI) | p Value |

| WB | ||||||

| Negative * | 13 | 2.0 | Ref | Ref | ||

| positive | 22 | 4.8 | 2.8 (0.4–5.2) | 0.022 | 3.0 (0.5–5.6) | 0.022 |

| Age-group | ||||||

| 18–<25 * | 9 | 3.5 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 25–<45 | 19 | 4.6 | 1.1 (−1.8–4.0) | 0.452 | −0.2 (−3.1–2.7) | 0.909 |

| 45–65 | 7 | 1.8 | −1.8 (−5.4–1.8) | 0.328 | −2.9 (−6.4–0.6) | 0.104 |

| Site | ||||||

| Kyela * | 3 | 2.3 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Lindi | 32 | 3.9 | 1.7 (−2.7–6.1) | 0.449 | 0.3 (−3.9–4.5) | 0.885 |

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | N = 61 * | N-positive (%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p Value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p Value |

| WB | ||||||

| Negative * | 34 | 8 (23.5) | Ref | Ref | ||

| positive | 27 | 10 (37.0) | 1.87 (0.63–5.55) | 0.259 | 4.07 (0.91–18.1) | 0.066 |

| Not performed ** | 1 * | - | - | - | - | - |

| HIV status | ||||||

| Negative * | 49 | 13 (26.5) | Ref | Ref | ||

| positive | 12 | 5 (41.7) | 1.98 (0.56–7.03) | 0.289 | 5.46 (0.88–33.66) | 0.068 |

| Age-group | ||||||

| 18–<25 * | 14 | 4 (28.6) | Ref | Ref | ||

| 25–<45 | 36 | 11 (30.6) | 1.05 (0.28–3.88) | 0.891 | 0.50 (0.10–2.42) | 0.402 |

| 45–65 | 11 | 3 (27.3) | 0.96 (0.18–5.07) | 0.943 | 0.49 (0.08–3.17) | 0.380 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mosoba, M.; Marandu, T.F.; Maganga, L.; Mhidze, J.; Mahenge, A.; Mnkai, J.; Urio, A.; Chiwarengo, N.; Torres, L.; John, W.; et al. Impact of Wuchereria bancrofti Infection on Cervical Mucosal Immunity and Human Papillomavirus Prevalence in Women from Lindi and Mbeya Regions, Tanzania. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 317. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10110317

Mosoba M, Marandu TF, Maganga L, Mhidze J, Mahenge A, Mnkai J, Urio A, Chiwarengo N, Torres L, John W, et al. Impact of Wuchereria bancrofti Infection on Cervical Mucosal Immunity and Human Papillomavirus Prevalence in Women from Lindi and Mbeya Regions, Tanzania. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2025; 10(11):317. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10110317

Chicago/Turabian StyleMosoba, Maureen, Thomas F. Marandu, Lucas Maganga, Jacklina Mhidze, Anifrid Mahenge, Jonathan Mnkai, Agatha Urio, Nhamo Chiwarengo, Liset Torres, Winfrida John, and et al. 2025. "Impact of Wuchereria bancrofti Infection on Cervical Mucosal Immunity and Human Papillomavirus Prevalence in Women from Lindi and Mbeya Regions, Tanzania" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 10, no. 11: 317. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10110317

APA StyleMosoba, M., Marandu, T. F., Maganga, L., Mhidze, J., Mahenge, A., Mnkai, J., Urio, A., Chiwarengo, N., Torres, L., John, W., Ngenya, A., Kalinga, A., Mwingira, U. J., Ritter, M., Hoerauf, A., Horn, S., Geldmacher, C., Hoelscher, M., Chachage, M., & Kroidl, I. (2025). Impact of Wuchereria bancrofti Infection on Cervical Mucosal Immunity and Human Papillomavirus Prevalence in Women from Lindi and Mbeya Regions, Tanzania. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 10(11), 317. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed10110317