A New Serious Game (e-SoundWay) for Learning English Phonetics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tools for Game Creation

- Hierarchical Tree: Enables the creation of screen elements and their interdependencies, including layered objects such as buttons, text, and images.

- Project Window: Hosts the organizational structure of assets and code modules used throughout the application.

- Scene and Game View: Provides a live preview of the interface, including audio-visual materials and user interactions.

- Inspector and Console: Allows developers to configure each element’s properties (e.g., size, position, behavior) and troubleshoot runtime issues.

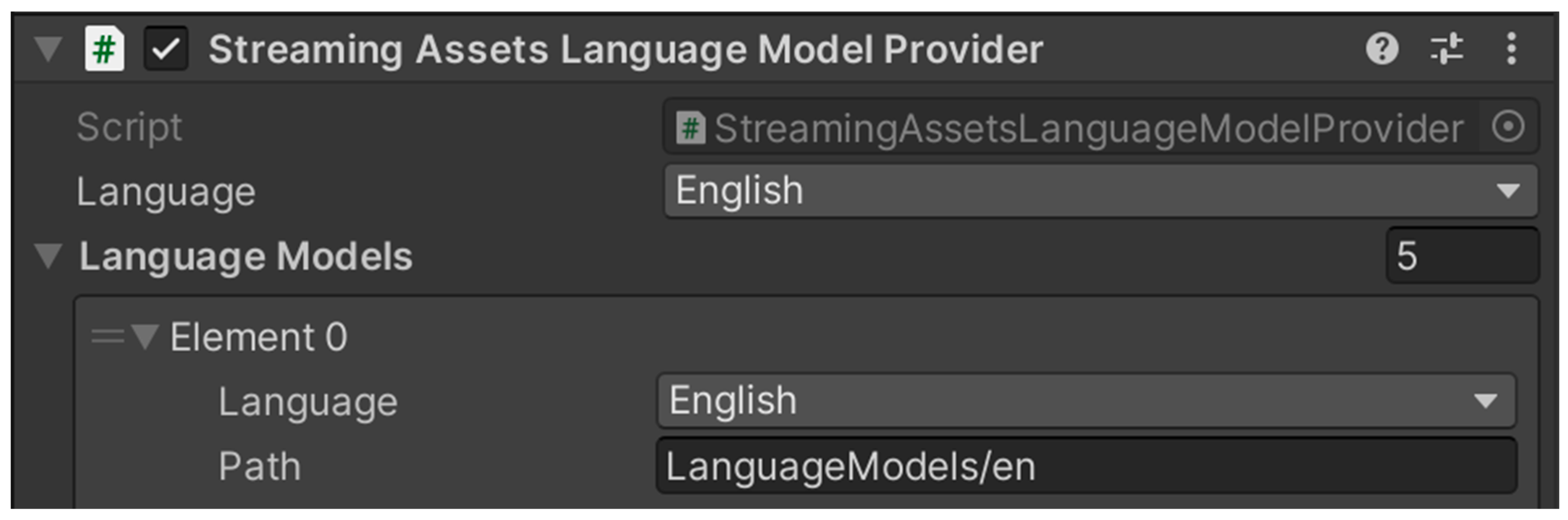

- Language Model Provider: References the target language model used to evaluate user speech input (see Figure 1). It specifies the location of the language-specific dictionaries and phonetic resources that support the speech recognition process.

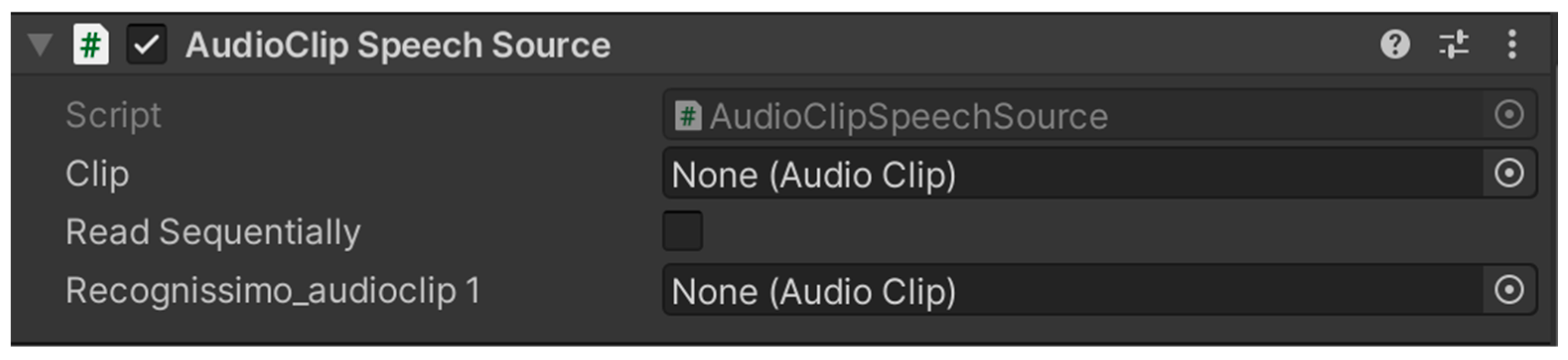

- Audio fragment as voice source: Handles incoming audio clips, including cleaning, segmentation, and preparation for recognition tasks (Figure 2). It is specifically used in gameplay sections that require temporary audio file creation for comparing user-generated speech with predefined reference samples. By preprocessing the audio input, this module improves the accuracy and reliability of the speech recognition system.

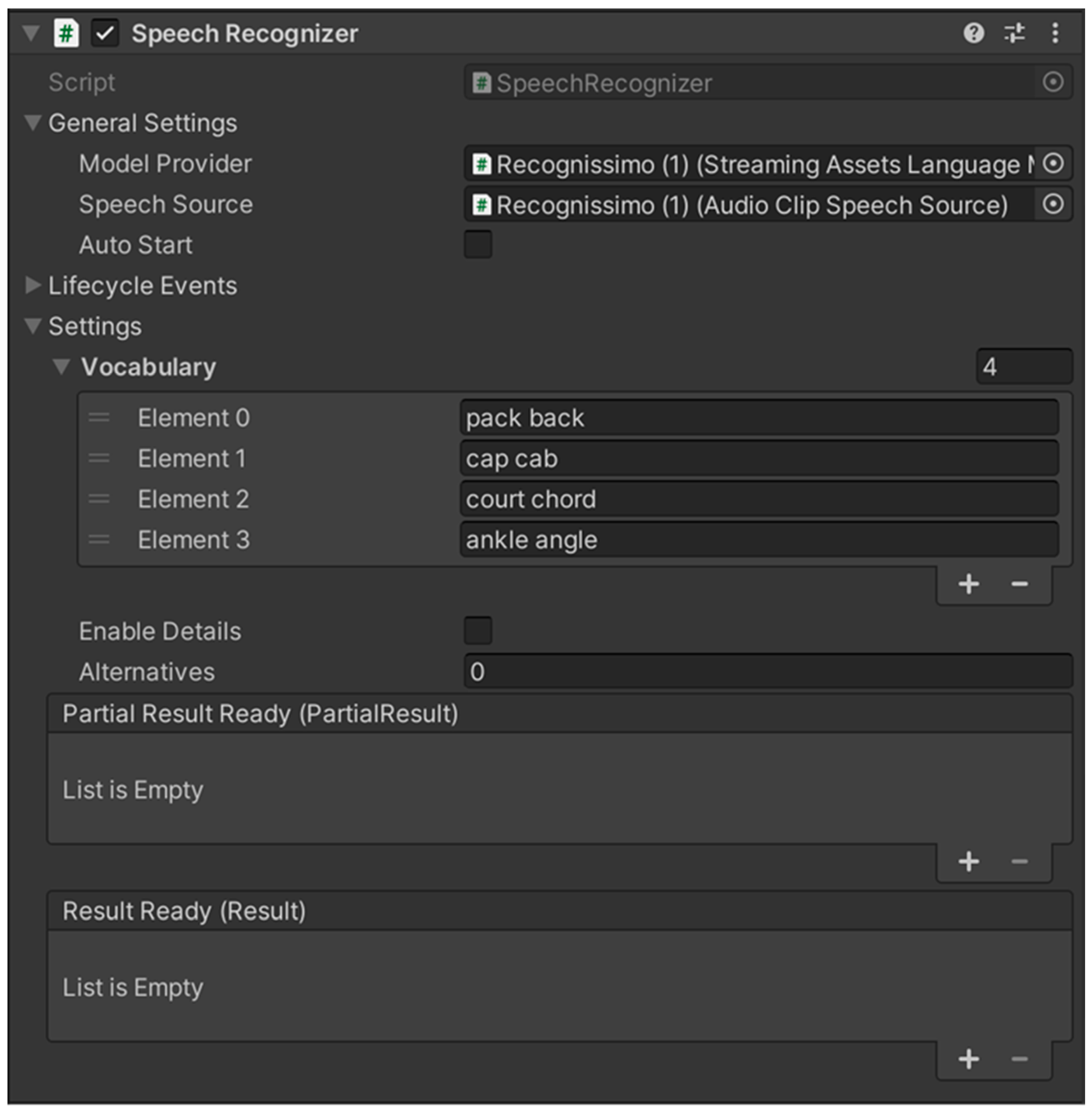

- Speech Recognizer: Executes the speech recognition process by integrating various program elements (Figure 3). It utilizes the target language configuration defined in the Language Model Provider and accepts input either directly from a microphone or from pre-recorded audio clips. Target words are dynamically assigned to guide the evaluation process. A dedicated function supports control and comparison algorithms, allowing the system to generate reference lists and assess learner output through tolerance thresholds and approximation-based matching.

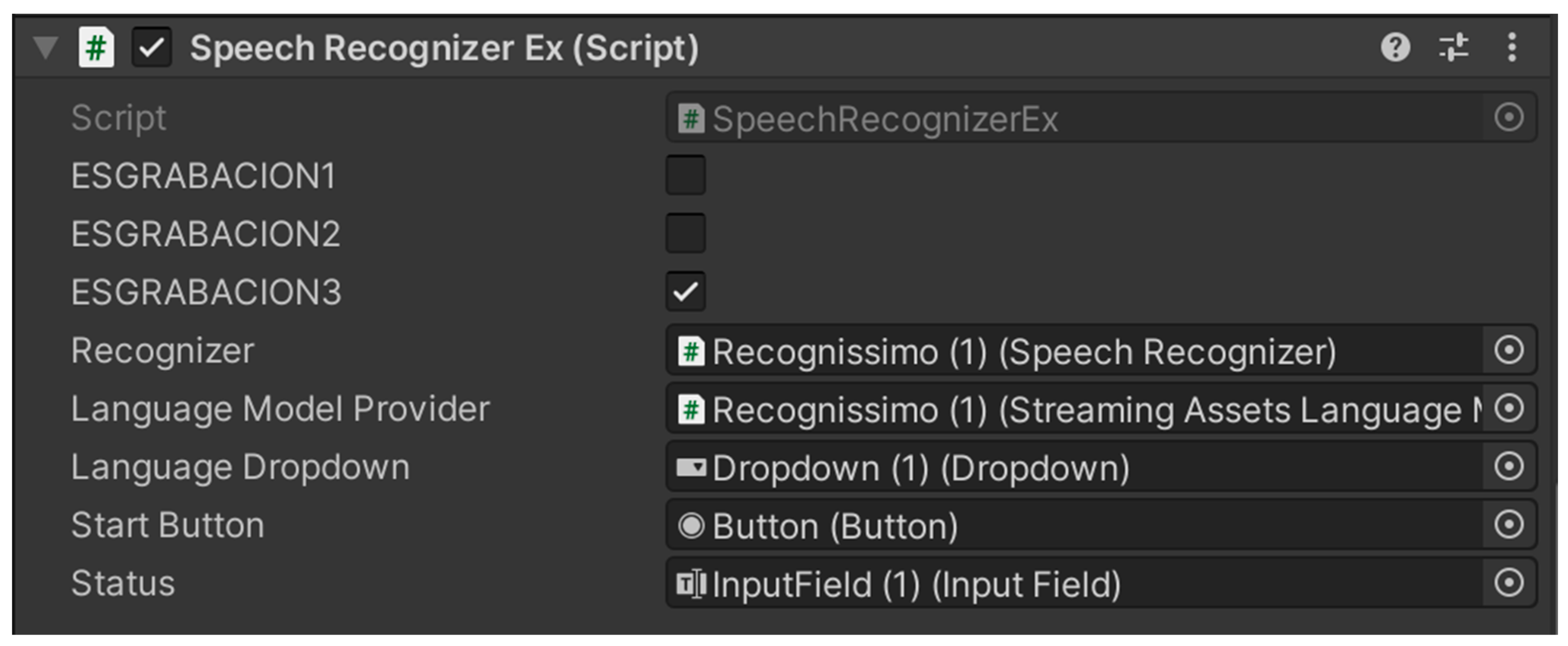

- External speech recognizer: Manages the execution of the speech recognition program based on the mini-game type selected (Figure 4). Within the development environment, a Boolean selector is used to configure the input format: short recordings for Listen and Repeat tasks (RECORDING1), medium-length recordings for Minimal Pairs (RECORDING2), and extended recordings for Connected Speech exercises (RECORDING3). This configuration ensures that the recognition system adapts accurately to the phonetic and temporal complexity of each task type.

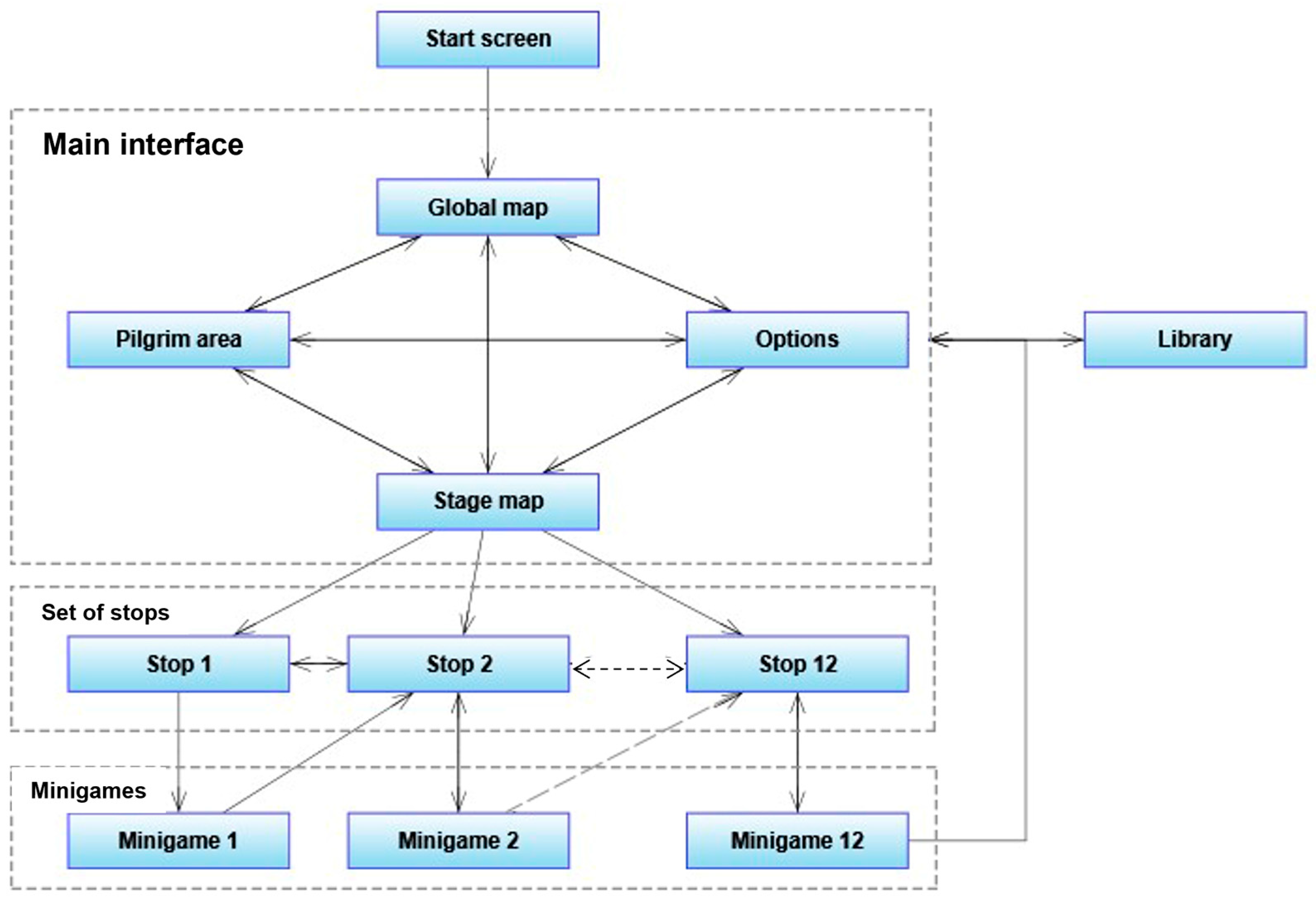

2.2. General Structure and Game Contents

2.2.1. Home Screen

2.2.2. Main Interface

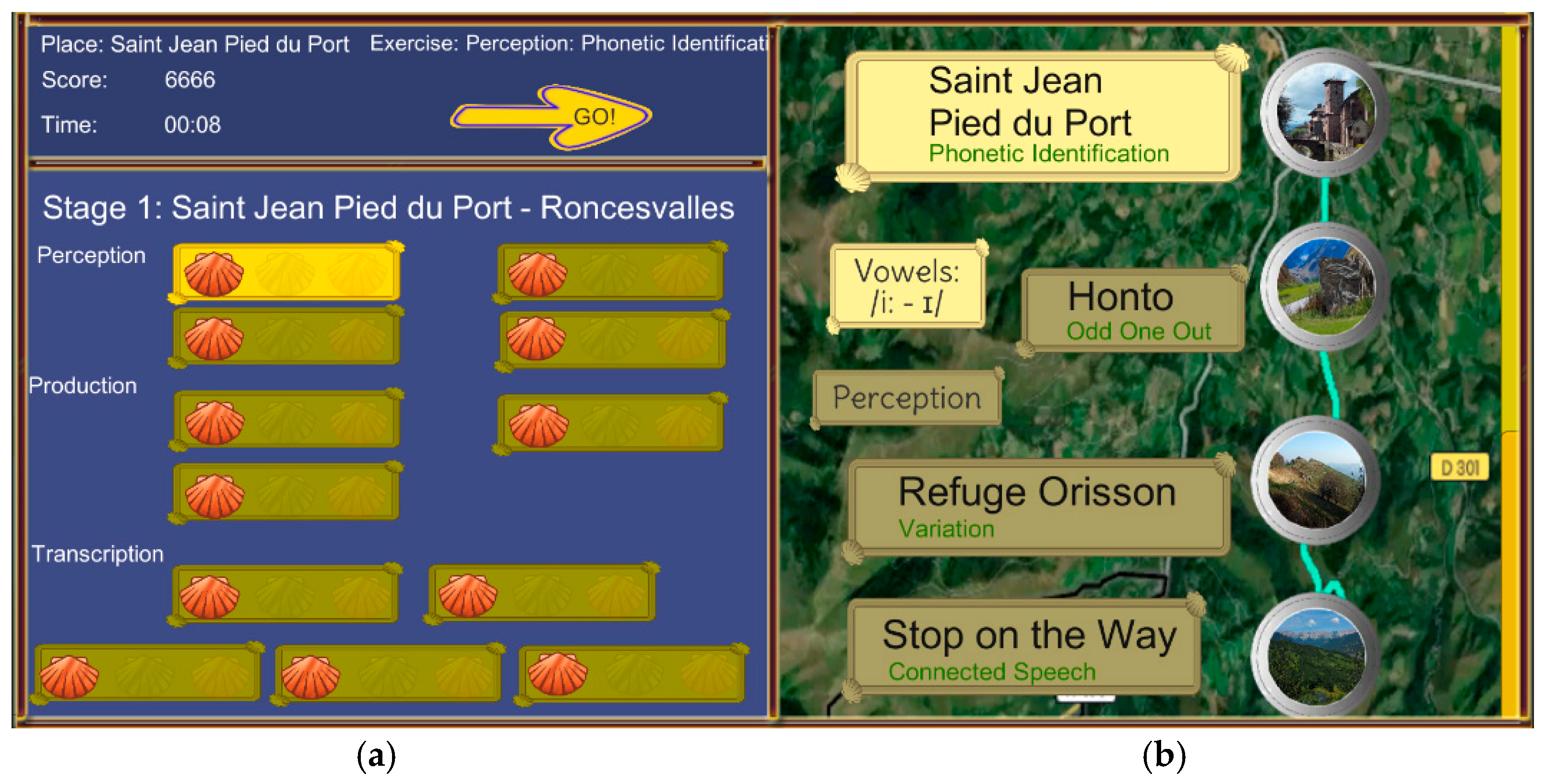

- Stage Map: Displays an image of a real section of the Camino de Santiago with interactive stop markers placed along the route (Figure 7). On the left side of the interface, a static frame presents information on player progress, including stop descriptions and a visual record of earned medals. Scallop shells, chosen for their cultural association with the Camino, represent achievement tiers: bronze, silver, or gold, awarded based on learner performance. The use of culturally grounded symbols aligns with findings by Lems [39], who emphasizes that familiar cultural cues increase emotional investment and deepen engagement with learning tasks. Each stage map includes interactive buttons programmed to activate animations, illuminate earned medals, and display stop-specific data such as time spent and phonetic scores. A “GO!” button becomes available once a stop is activated, allowing learners to continue their journey. Across the platform, 34 stage maps provide unique content and visual references while maintaining a consistent interaction logic.

- The Global Map (“The Way”): includes hidden actuators that, once triggered, load associated stage data and dynamically generate the relevant interface elements. This modular design supports data-driven content delivery and simplifies stage transitions, enhancing both navigational clarity and scalability [35].

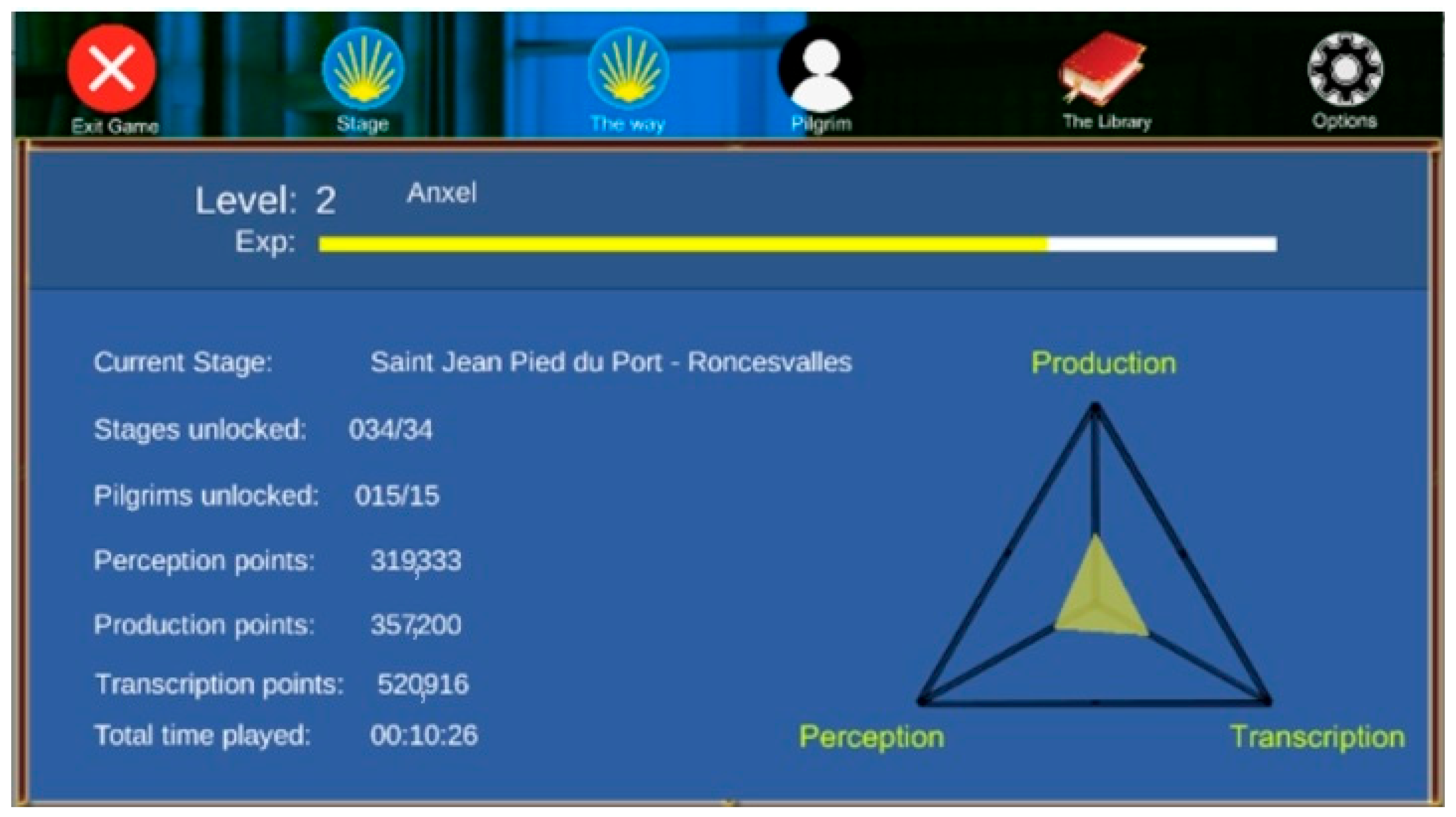

- The Pilgrim Zone: Includes a personalized learning dashboard (see Figure 8) that provides learners with real-time feedback on their current stage, accumulated scores, unlocked content, and overall progress across three core skill areas: perception, production, and transcription. These competencies are visually represented in a dynamic 3D pyramid, which reflects the learner’s advancement along each dimension. Additional features, such as an experience bar and a usage time clock, are incorporated to promote sustained engagement, metacognitive awareness, and effective time management, in accordance with established principles of serious game design [33,34]. Consistent with other EFL-focused serious games [23,24], e-SoundWay adopts a scaffolded, performance-based learning path grounded in the EPSS model. This structure ensures a gradual increase in phonetic and phonological complexity, thereby supporting effective and individualized pronunciation development.

- The Options Panel: Provides basic configuration tools, such as adjusting game audio levels and resetting progress. Selecting the reset option deletes all persistent data tied to the player profile, restoring the game to its default state. This functionality supports both usability testing and learner control, two features highlighted ineffective CALL platform design [24,27].

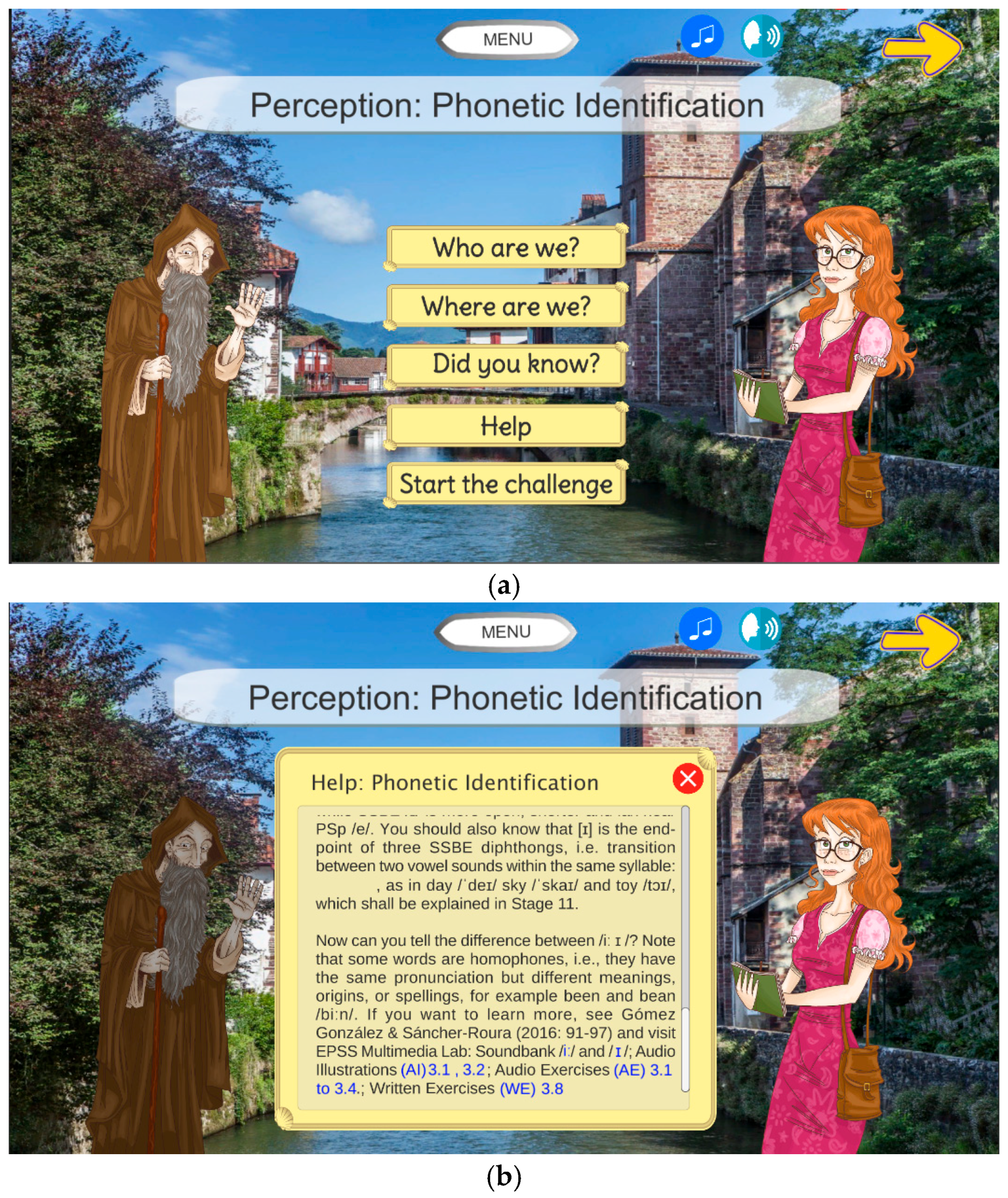

2.2.3. Stop Screens

2.2.4. The Library as a Multimodal Resource

2.2.5. Scoring System and Game Progress

if (success < mistakes) → 0

2.2.6. Structure of the Mini-Games

Perception

- Odd one out: Players listen to four items and select the phonologically distinct one (A-B-A-A, B-A-A-A) (Figure 12b). Focusing on phonetic discrimination, i.e., comparing sounds and deciding whether they are the same or different, these activities build categorical perception and raise awareness of subtle L2 contrasts, often without requiring explicit labeling [6,42].

- Variation: These mini-games train learners to recognize phonetic variants, both context-driven and accent-based, by exposing them to multiple realizations of target phonemes (Figure 12c). This fosters flexible listening and perceptual tolerance, aligning with research that stresses the need to prepare learners for phonetic diversity in real-world speech (Setter & Jenkins [44]; Munro & Derwing [45]) and supports the development of robust phonological categories and speech convergence (Bradlow et al. [42]).

- Connected speech. Learners identify target sounds embedded in naturalistic text. By interacting with audio and receiving visual feedback, they develop an awareness of linking, assimilation, and reduction (Figure 12d). Strange and Shafer [41] and Wang and Munro [46] both advocate for such training to improve real-world listening comprehension.

Production

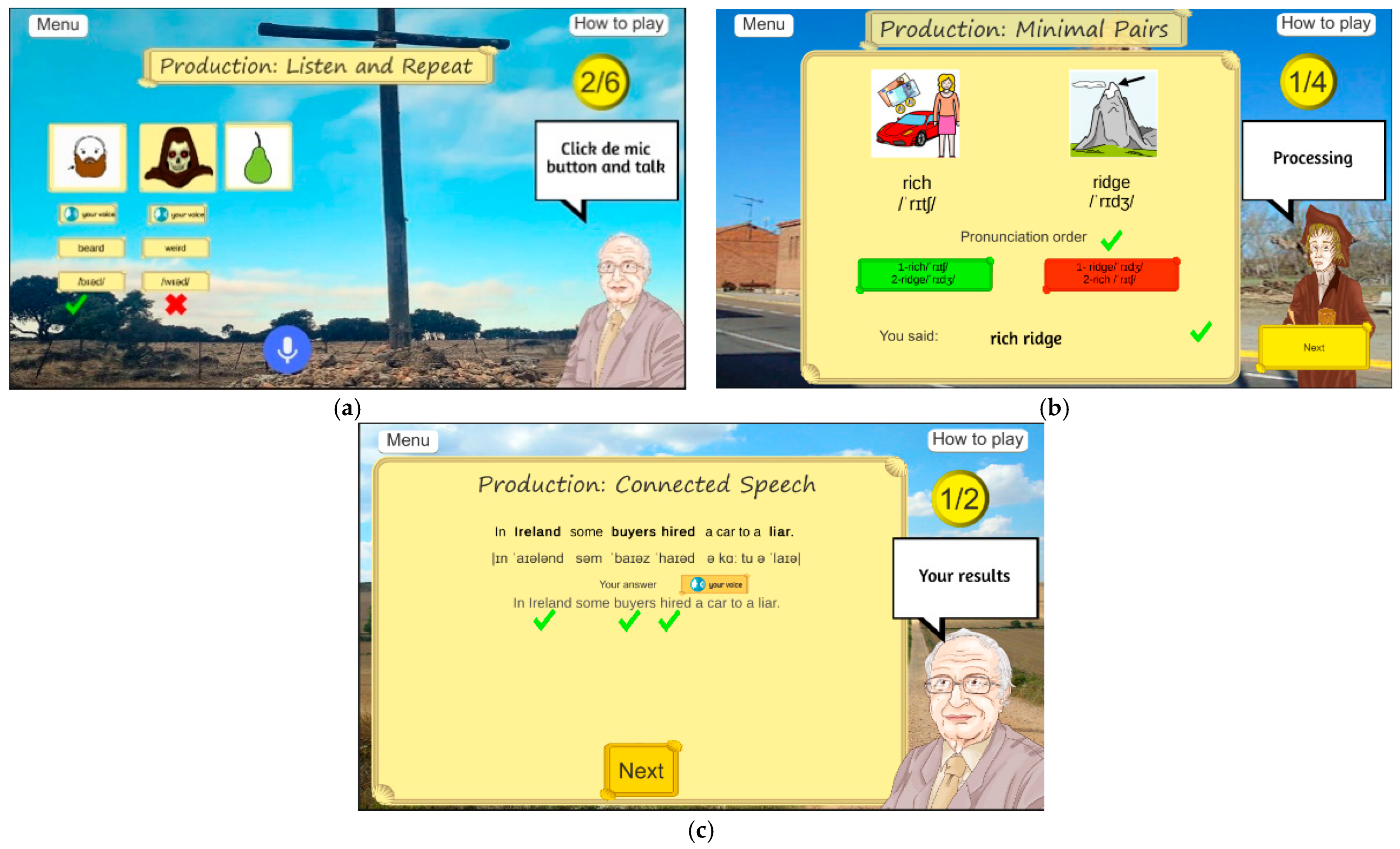

- Listen and Repeat tasks are rooted in traditional mimicry-drill techniques, where learners attempt to replicate the target sound after auditory exposure (Figure 13a). Wang and Munro [46], among others, demonstrated that, despite their simplicity, such drills remain effective for developing articulatory precision, particularly when paired with immediate feedback and visual reinforcement. It is therefore assumed that computer-assisted listen-and-repeat tasks will improve sound contrast production and lead to measurable gains in intelligibility and learner confidence.

- Minimal pairs: Provide contrastive practice with phonemes that are especially challenging for EFL learners. By requiring learners to differentiate and articulate pairs of words that differ in the pronunciation of one, often challenging phoneme, these tasks promote fine-grained phonological awareness and motor control (Figure 13b), as previously found by authors like Bradlow et al. [42] or Lengeris and Hazan [43]. They explained that explicit minimal pair training leads to improvements in both perception and production, especially when it incorporates high-variability input across speakers and contexts.

- Connected speech mini-games focus on the natural flow of spoken English, requiring learners to articulate word sequences that exhibit phonetic processes such as assimilation, linking, and elision (Figure 13c). These features often contribute to reduced intelligibility among EFL speakers who have primarily trained on isolated words or canonical forms. Studies such as those by Jenkins [44] emphasize that connected speech awareness is critical for developing rhythm, fluency, and listener-oriented intelligibility. Training learners to perceive and produce connected speech patterns equips them with the tools to understand rapid, native-like speech and to improve their own prosodic delivery in extended utterances. Incorporating connected speech into production tasks also supports the communicative goal of pronunciation instruction, which is not only accuracy but also comprehensibility in real-world interaction [45].

Transcription

- Missing symbols: In these mini-games, learners are required to fill in missing phonemes within a set of words displayed on the screen in order to reinforce sound-symbol associations and test learners’ segmental decoding accuracy [46]. Unlike in identification tasks, here learners must select phonemic symbols from a virtual IPA keyboard to complete the word forms. The player can overwrite previously placed entries before finalizing their response using the “Check” button (Figure 14a).

- Direct transcription mini-games require learners to transcribe full words from graphemes into phonemic script, in line with Wang and Munro’s [45] suggestion that transcription-based tasks improve learners’ sensitivity to non-native vowel contrasts and provide insight into their own production limitations. Audio support is provided for each word, and users interact with the IPA keyboard to generate phonological representations. The format mirrors authentic tasks used in pronunciation instruction to strengthen learners’ understanding of English spelling-pronunciation irregularities (Figure 14b).

- Reverse transcription: Learners are given phonemic transcriptions and must produce the corresponding graphemic forms. The game employs a QWERTY keyboard and allows for multiple correct spellings, as one phoneme string may correspond to several orthographic variants. The evaluation system accounts for such variability, penalizing only duplicated or incorrect entries while accommodating lexical diversity (Figure 14c). As in the previous case, these minigames intend to enhance learners’ decoding strategies and are especially relevant for those who struggle with the irregularities of English spelling conventions.

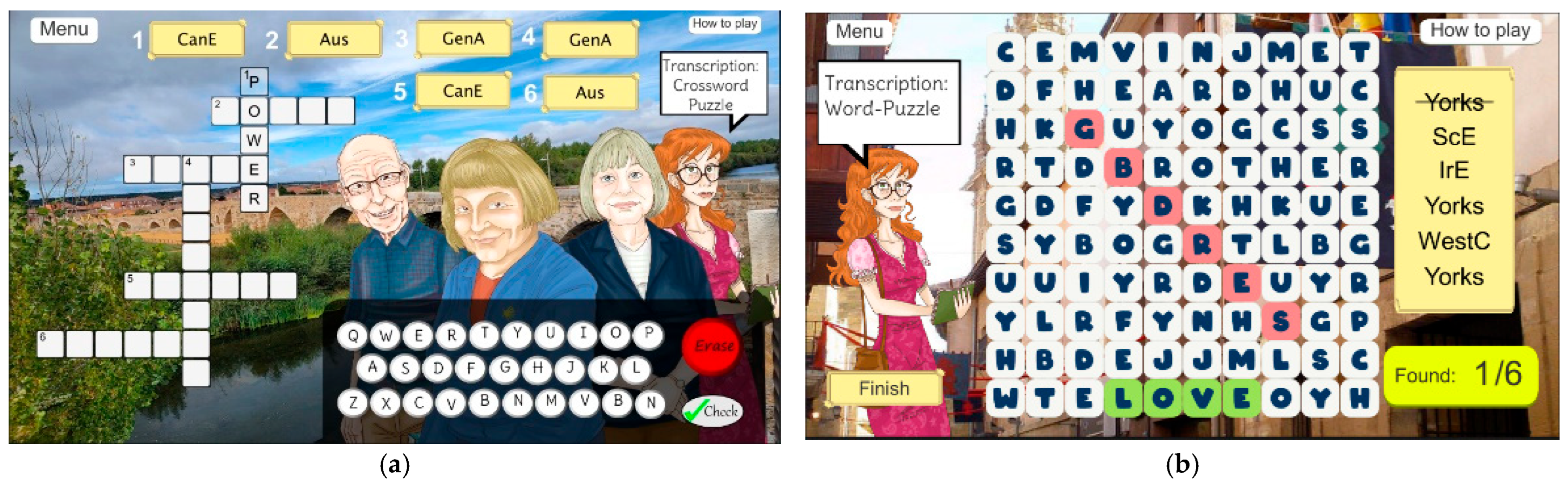

- Crossword. In these interactive puzzles, players complete a crossword grid using either phonemes or graphemes, depending on the given clues. The clues may include audio, IPA symbols, or graphemic hints, and the keyboard script dynamically updates each entry and score. Evaluation is based on the correctness of full entries, though the task avoids penalizing partial errors. This game helps consolidate learners’ segmental and suprasegmental awareness across multiple word forms (Figure 15a). as suggested by authors like Setter and Jenkins [44], who note that explicit transcription activities enhance learners’ ability to monitor their own pronunciation more effectively over time.

- Word puzzle: In these mini-games, players must locate words within a grid using graphemes, phonemes, or only audio clues. Increased difficulty is introduced in stages involving accent confrontation, where audio becomes the primary input. The grid is dynamically generated using stored lexical data, and correct matches are highlighted visually and aurally (Figure 15b). This task promotes orthographic and phonemic scanning skills, crucial for real-time decoding and listening comprehension [41,44].

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Research Questions

- To what extent does the use of e-SoundWay improve Spanish-speaking university EFL learners’ performance in phonetic perception, production, and transcription as measured by pre- and post-intervention tests?

- How do learners perceive the pedagogical effectiveness, usability, and motivational value of the e-SoundWay platform according to post-intervention user experience questionnaires?

2.3.2. Research Design

2.3.3. Participants

2.3.4. Player Progression and Level System

2.3.5. Instruments

2.3.6. Procedure

2.3.7. Data Analysis

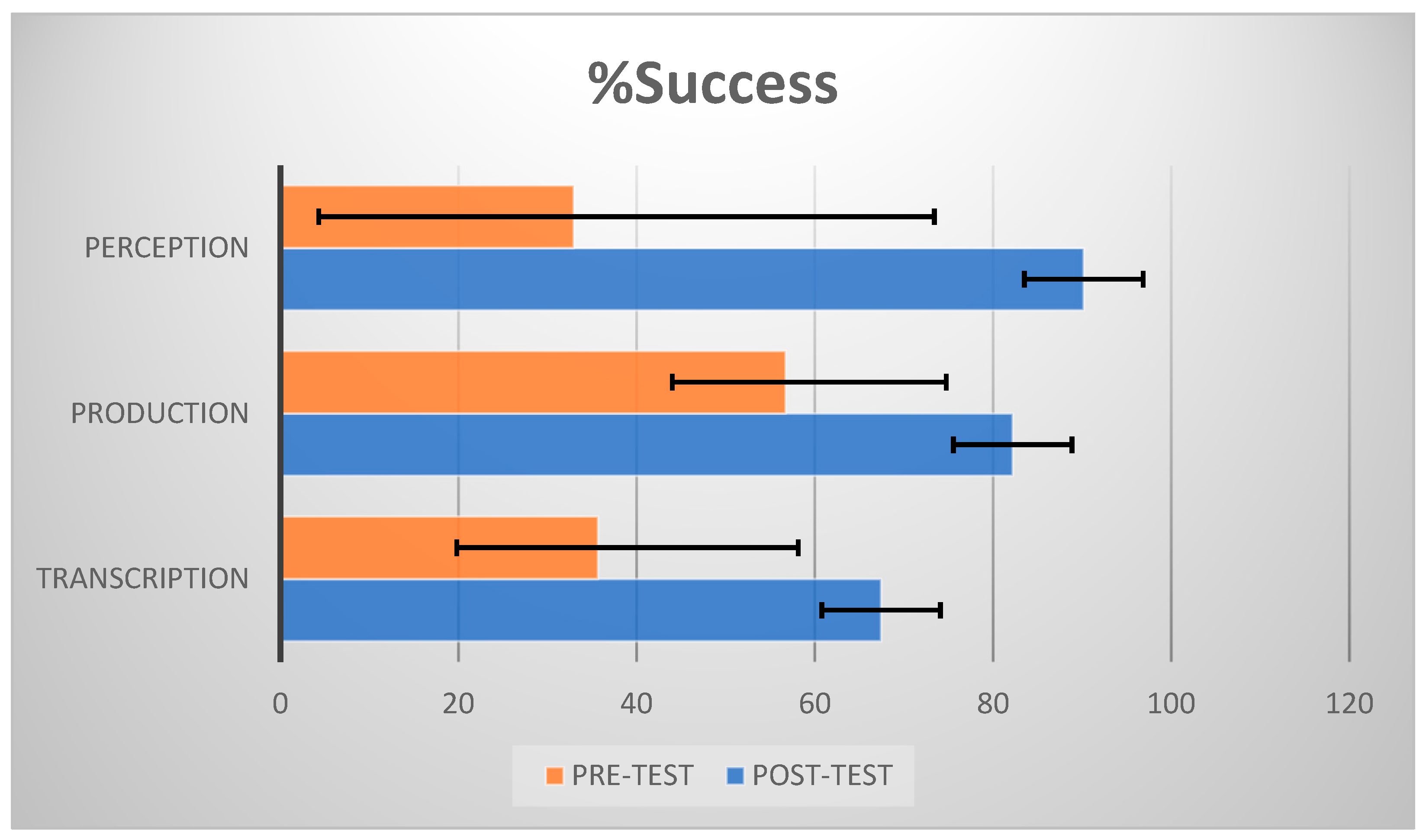

3. Results

3.1. Pre-/Post-Tests

- In Perception, the standard deviation decreased from 0.0284 to 0.0070.

- In Production, it dropped from 0.0669 to 0.0197.

- In Transcription, it declined from 0.0444 to 0.0111.

3.2. User Experience Questionnaire

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Language Policy Programme Education Policy Division, Education Department, Council Europe. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment—Companion; Editorial Council of Europe Publishing: Strasbourg, France, 2020; 278p. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho Marti, M.; Estévez-González, V.; Esteve Mon, F.M.; Gisbert Cervera, M.M.; Lázaro Cantabrana, J.L. Capítulo XIV. Indicadores de Calidad para el uso de las TIC en los Centros Educativos. Compartir Aprendizaje. Editorial Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, Sapin. 2014. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11797/imarina9149374 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Salinas, J. Innovación Educativa y Uso de las TIC. Editorial Universidad Internacional de Andalucía, Andalucía, Spain, 2008-09, 15–30. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10334/136 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Clark, R.C.; Mayer, R.E. E-Learning and the Science of Instruction: Proven Guidelines for Consumers and Designers of Multimedia Learning, 3rd ed.; Pfeiffer: Zurich, Switzerland, 2011; 528p. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A.; Carlile, O.; Stack, A. Approaches to Learning: A Guide for Teachers; McGraw Hill Education: London, UK, 2008; 278p. [Google Scholar]

- Derwing, T.M.; Munro, M.J. Pronunciation Fundamentals: Evidence-based perspectives for L2 teaching and research. In Language Learning & language Teaching; John Benjamin Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; 208p. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, M. Culture, culture learning and new technologies: Towards a pedagogical framework. Lang. Learn. Lang. Teach. 2007, 11, 104–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Z.; Avadoust, V. A review of the methodological quality of quantitative mobile-assisted language learning research. System 2021, 100, 102568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago Ferreiro, A.; Gómez González, M.Á.; Fragueiro Agrelo, Á.; Llamas Nistal, M. Mulit-platform application for learning English phonetics: Serious Game. In Proceedings of the XV Technologies Applied to Electronics Teaching Conference, Teruel, Spain, 29 June–1 July 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, C.; Vavoula, G.N.; Glew, J.P.; Taylor, J.; Sharples, M.; Lefrere, P.; Lonsdale, P.; Naismith, L.; Waycott, J. Guidelines for Learning/Teaching/Tutoring in a Mobile Environment. Mobilearn Project Deliverable. 2005. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280851673_Guidelines_for_learningteachingtutoring_in_a_mobile_environment (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Hwang, W.Y.; Chen, H.S.L.; Shadiev, R.; Huang, R.Y.-M.; ChenImproving, C.-Y. English as a foreign language writing in elementary schools using mobile devices in familiar situational context. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2014, 27, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.Y.; Chen, H.S. Users’ familiar situational contexts facilitate the practice of EFL in elementary schools with mobile devices. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2013, 26, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H. Integrating self-paced mobile learning into language instruction: Impact on reading comprehension and learner satisfaction. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2017, 25, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrigglesworth, J. Using smartphones to extend interaction beyond the EFL classroom. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2019, 33, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burston, J. Twenty years of MALL project implementation: A meta-analysis of learning outcomes. ReCALL 2015, 27, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.M.; Chen, L.C.; Yang, S.M. An English vocabulary learning app with self-regulated learning mechanism to improve learning performance and motivation. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2019, 32, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, F.; Rezvani, R.; Faceli, S. Social networks and their effectiveness in learning foreign language vocabulary: A comparative study using WhatsApp. CALL-EJ 2017, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Elekaei, A.; Tabrizi, H.H.; Chalak, A. Investigating the Effects of EFL Learners’vocabulary gain and retention levels on their choice of memory and compensation strategies in an e-learning project. CALL-EJ 2019, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez González, M.Á.; Sánchez Roura, T. English Pronunciation for Speakers of Spanish: From Theory to Practice; Editorial De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez González, M.Á.; Lago Ferreiro, A. Computer-Assisted Pronunciation Training (CAPT): An empirical evaluation of EPSS Multimedia Lab. Lang. Learn. Lang. Teach. 2024, 28, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez González, M.Á.; Lago Ferreiro, A. Web-assisted instruction for teaching and learning EFL phonetics to Spanish learners: Effectiveness, perceptions and challenges. Comput. Educ. Open 2024, 7, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardisty, D.; Windeatt, S. Computer-Assisted Language Learning; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1989; 165p. [Google Scholar]

- Chansarian-Dehkordi, F.; Ameri-Golestan, A. Effects of mobile learning on acquisition and retention of vocabulary among Persian-speaking EFL learners. CALL-EJ 2016, 17, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson-Revell, P.M. Computer-Assisted Pronunciation Training (CAPT): Current issues and future directions. RELC J. 2021, 52, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colferai, E.; Gregory, S. Minimizing attrition in online degree courses. J. Educ. Online 2015, 12, 62–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracke, E. A road to understanding: A qualitative study into why learners drop out of a blended language learning (BLL) environment. ReCALL 2007, 19, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz de Carvalho, C.; Coelho, A. Game-Based Learning, Gamification in Education and Serious Games. Computers 2022, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, M.H. Students’ reactions to using smartphones and social media for vocabulary feedback. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2019, 32, 920–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouz-González, J. Pronunciation instruction through twitter: The case of commonly mispronounced words. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2017, 30, 631–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Lin, C.-H.; You, J.; Shen, H.J.; Qi, S.; Luo, L. Improving the English-speaking skills of young learners through mobile social networking. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2017, 30, 304–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskeliünas, R.; Kulikajevas, A.; Blažauskas, T.; Damaševičius, R.; Swacha, J. An Interactive Serious Mobile Game for Supporting the Learning of Programming in JavaScript in the Context of Eco-Friendly City Management. Computers 2020, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, C.; Ecalle, J.; Magnan, A.A. Serious games as new educational tools: How effective are they? A meta-analysis of recent studie. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2013, 29, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhash, S.; Cudney, E.A. Gamified learning in higher education: A systematic review of the literature. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 87, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Sridharan, H.; Koepke, L.; Singh, S.; Boiko, R. Learning and engagement in a gamified course: Investigating the effects of student characteristics. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2018, 34, 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, J.P.; Silveira, I.F. A Systematic Review on Open Educational Games for Programming Learning and Teaching. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2020, 15, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unity User Manual 2023.1. Available online: https://docs.unity3d.com/2023.1/Documentation/Manual/UnityManual.html (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Recognissimo Documentation. Available online: https://bluezzzy.github.io/recognissimo-docs/ (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Allen, M.L.; Hartley, C.; Cain, K. Do iPads promote symbolic understanding and word learning in children with autism? Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lems, K. New Ideas for Teaching English Using Songs and Music. Engl. Teach. Forum 2018, 56, 14–21. Available online: https://americanenglish.state.gov/files/ae/resource_files/etf_56_1_pg14-21_0.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Peterson, M.; Jabbari, N. Digital Games in Language Learning: Case Studies and Applications; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: Oxfordshire, UK, 2023; 202p. [Google Scholar]

- Strange, W.; Shafer, V.L. Speech perception in second language learners: The re-education of selective perception. In Phonology and Second Language Acquisition; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 153–191. [Google Scholar]

- Bradlow, A.R.; Pisoni, D.B.; Akahane-Yamada, R.; Tohkura, Y. Training Japanese listeners to identify English /r/ and /l/: Long-term retention of learning in perception and production. Percept. Psychophys. 1997, 59, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengeris, A.; Hazan, V. The effect of native vowel processing ability and frequency discrimination acuity on the phonetic training of English vowels for native Greek listeners. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2010, 128, 3757–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, J.; Setter, J. Teaching English pronunciation: A state of the art review. Lang. Teach. 2005, 38, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, M.J.; Derwing, T.M. The functional load principle in ESL pronunciation instruction: An exploratory study. System 2006, 34, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Munro, M.J. Computer-based training for learning English vowel contrasts. System 2004, 32, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lively, S.E.; Logan, J.S.; Pisoni, D.B. Training Japanese listeners to identify English /r/ and /l/: II. The role of phonetic environment and talker variability in learning. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1993, 94, 1242–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, J.S. On phonetic convergence during conversational interaction. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2006, 119, 2382–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| % Success | Points | Scallop Shell Medals |

|---|---|---|

| 0% < X < 50% | 3 | None |

| 50% ≤ X < 75% | 5 | Bronze |

| 75% ≤ X < 90% | 7 | Silver |

| 90% ≤ X ≤ 100% | 10 | Gold |

| Number | Question |

|---|---|

| 1 | What is your occupation? |

| 2 | How many hours a day are you online? |

| 3 | How long do you devote to playing games online? |

| 4 | What kind of games do you play? |

| Number | Question |

|---|---|

| 5 | Are the instructions to play clear enough? |

| 6 | Do you find the interactivity of the game is user-friendly? |

| 7 | Do you find it challenging enough? |

| 8 | Does e-SoundWay feel like a game? |

| 9 | Which was the most difficult game section? |

| 10 | Do you think you have improved your level in English Phonetics and Phonology? |

| 11 | How satisfied are you with e-SoundWay as a whole? |

| 12 | Would you recommend this game to others in your situation? |

| Question | Summary/Distribution | Interpretive Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Q1: Participant type | 91% undergraduate | Homogeneous academic cohort |

| Q2: Daily internet use | 64% (2–4 h), 18% (1–2 h), 18% (>4 h) | High internet usage |

| Q3: Daily gaming time | 64% (<30 min), 27% (30–60 min), 9% (>2 h) | Low gaming engagement |

| Q4: Prior experience with serious games | 21% Yes, 79% No | No significant impact on Q5 |

| Q5: Instruction clarity | 73% Clear, 18% Not always clear | Generally positive |

| Q6: Prior experience vs Q5 (Chi-square) | χ²(2, N = 91) = 1.84, p = 0.398 | No significant association |

| Q7: Daily gaming vs engagement (ANOVA) | F(2, 88) = 4.67, p = 0.012 (Tukey: 30–60 min > rare) | Moderate gamers more engaged |

| Q8: Perceived game-likeness | 55% Game-like, 27% Challenging, 9% Exercise-like | Subjective perceptions varied |

| Q9: Most difficult phonetic task | 64% Transcription, 18% Production, 9% Perception | Friedman χ2(2) = 36.5, p < 0.001; transcription hardest |

| Q10: Perceived improvement | Strongly Agree (39%), Agree (42%), Neutral (12%), Disagree (6%), No answer (1%) | Positive overall; high agreement |

| Q11: Overall satisfaction | Very satisfied (36%), Satisfied (45%), Neutral (13%), Dissatisfied (4%), No answer (2%) | Correlated with Q10; generally high satisfaction |

| Q12: Willingness to recommend | Definitely (49%), Probably (36%), Not sure (10%), Probably not (4%), No answer (1%) | The majority would recommend the tool |

| Q10 vs Q11 (Pearson correlation) | r = 0.52, p < 0.001 | Moderate, significant correlation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lago-Ferreiro, A.; Gómez-González, M.Á.; López-Ardao, J.C. A New Serious Game (e-SoundWay) for Learning English Phonetics. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2025, 9, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti9060054

Lago-Ferreiro A, Gómez-González MÁ, López-Ardao JC. A New Serious Game (e-SoundWay) for Learning English Phonetics. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction. 2025; 9(6):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti9060054

Chicago/Turabian StyleLago-Ferreiro, Alfonso, María Ángeles Gómez-González, and José Carlos López-Ardao. 2025. "A New Serious Game (e-SoundWay) for Learning English Phonetics" Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 9, no. 6: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti9060054

APA StyleLago-Ferreiro, A., Gómez-González, M. Á., & López-Ardao, J. C. (2025). A New Serious Game (e-SoundWay) for Learning English Phonetics. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 9(6), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti9060054