Bloom: Scaffolding Multiple Positive Emotion Regulation Techniques to Enhance Casual Conversations and Promote the Subjective Well-Being of Emerging Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Positive Casual Conversations Through Positive Emotion Regulation

2.2. First-Person Method: Autobiographical Research Through Design

2.3. Experiential-Versus-Didactic Emotion Regulation Technologies

3. Developing Bloom: A Prototype to Facilitate Flourishing Conversations

3.1. Applying Autobiographical Research Through Design

3.2. Positive Emotion Regulation Technique Selection Process

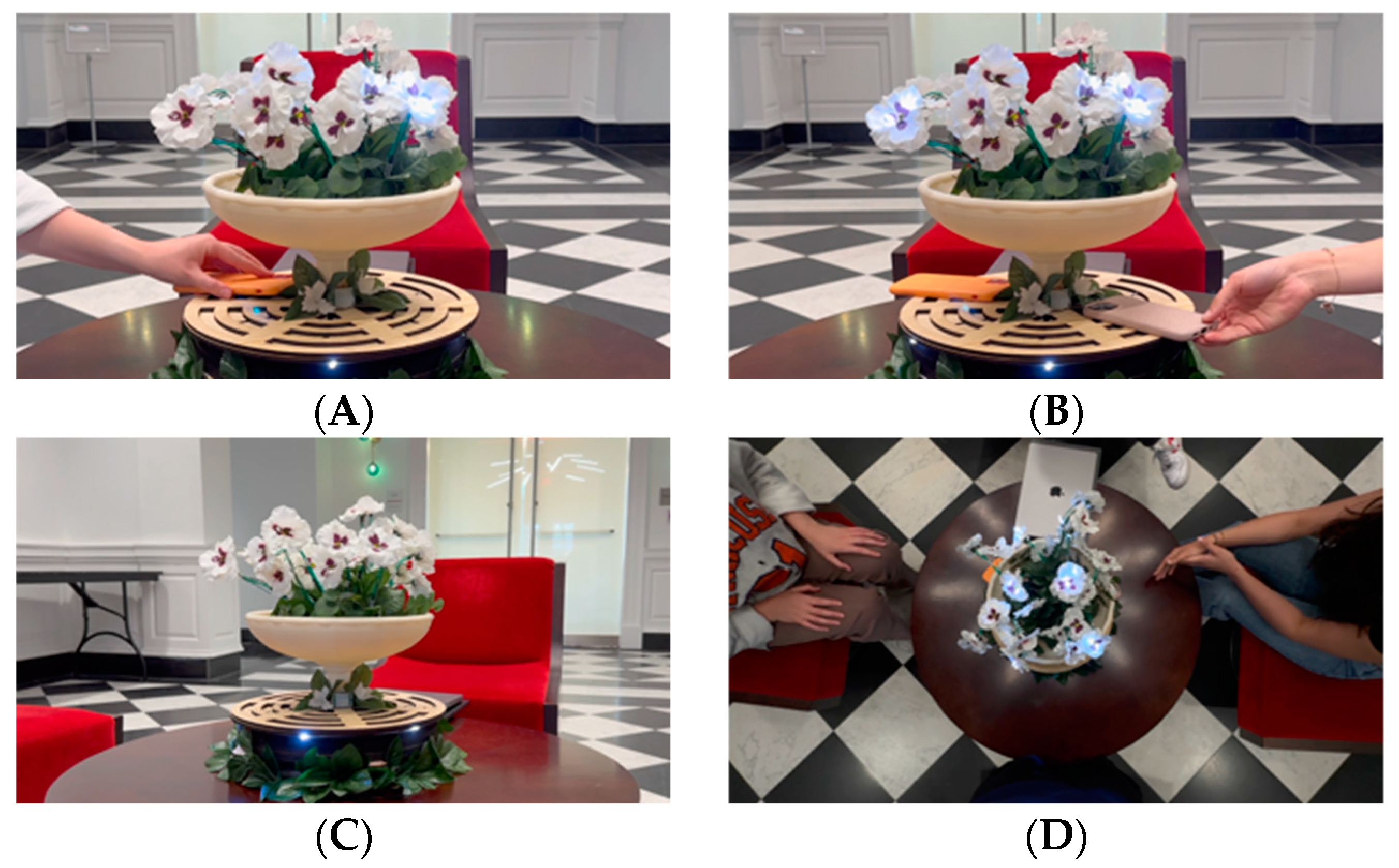

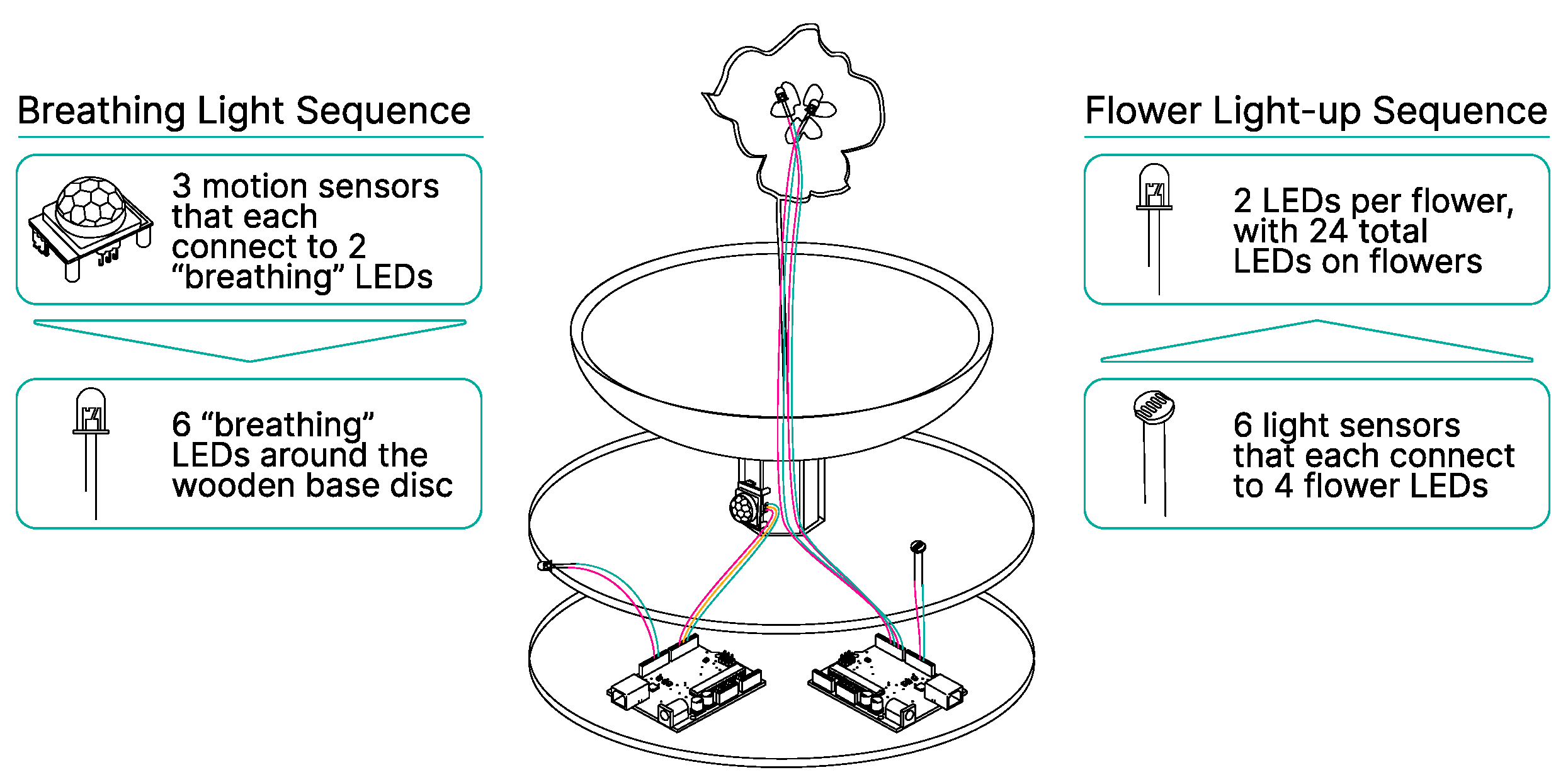

3.3. Process Prototype Design and Interaction Scenarios

- Late-night dorm room hangout: After finishing their study sessions, a group of students gathers spontaneously in their dormitory lounge. They sink into the couches and place their phones on Bloom, ready for a relaxed conversation to unwind from the day.

- Being immersed and absorbed: As Bloom’s flowers light up, the students become absorbed in conversation. They discuss lighthearted topics such as favorite music, campus gossip, and travel plans. Bloom’s gentle glow helps them stay in the moment, free from phone distractions.

- Engaging in a collective: Each phone placed on Bloom activates more lights, a subtle reminder of their shared engagement. The collective lighting reflects the inclusive, relaxed atmosphere, making everyone feel connected to the group.

- Creating a savoring atmosphere: The soft, ambient light transforms the casual hangout into a warm, inviting space. In this relaxed mood, time seems to slow, and students feel comfortable sharing deeper thoughts about their future dreams.

- Sharing the positive experience with others: The group exchanges funny stories from the week, laughing and bonding over shared experiences. They often note how much they are enjoying this low-key hangout, with Bloom’s light serving as a visual reminder of their time together.

- Infusing the ordinary with special meaning: Bloom elevates what could have been an ordinary late-night chat into something special. The device transforms a spontaneous gathering into a memorable moment, leaving the group feeling more connected and refreshed.

4. Evaluation: Experiences of Using and Living with Bloom

4.1. Method and Data Analysis

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Initial Experiences

4.2.2. Integrating Bloom into Daily Life

4.2.3. Contextual Factors

4.2.4. Enhancing Social Interactions

4.2.5. Interpersonal Dynamics

4.2.6. Challenges and Adaptations

4.2.7. Evolution over Time

4.2.8. Other Findings—Additional PER Activities

5. Discussion

5.1. Methodological and Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Key Interaction Qualities of Bloom That Contributed to Facilitating Casual Conversations

5.2.1. Social Accountability

5.2.2. Autonomy and Open-Endedness

5.2.3. Fit with Context and Enhanced Visibility

5.3. Limitations and Future Study Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnett, J.J.; Žukauskienė, R.; Sugimura, K. The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Halliburton, A.E.; Hill, M.B.; Dawson, B.L.; Hightower, J.M.; Rueden, H. Increased stress, declining mental health: Emerging adults’ experiences in college during COVID-19. Emerg. Adulthood 2021, 9, 433–448. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, S.H.; Schaub, J.P.; Nagata, J.M.; Park, M.J.; Brindis, C.D.; Irwin, C.E., Jr. Young adult anxiety or depressive symptoms and mental health service utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 70, 985–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senter, M.S. The impact of social relationships on college student learning during the pandemic: Implications for sociologists. Teach. Sociol. 2024, 52, 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gonza, G.; Burger, A. Subjective well-being during the 2008 economic crisis: Identification of mediating and moderating factors. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 18, 1763–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibe, S.; Blanchard-Fields, F. Effects of regulating emotions on cognitive performance: What is costly for young adults is not so costly for older adults. Psychol. Aging 2009, 24, 217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Weinstein, N. Can you connect with me now? How the presence of mobile communication technology influences face-to-face conversation quality. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2013, 30, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büttner, C.M.; Gloster, A.T.; Greifeneder, R. Your phone ruins our lunch: Attitudes, norms, and valuing the interaction predict phone use and phubbing in dyadic social interactions. Mob. Media Commun. 2022, 10, 387–405. [Google Scholar]

- Kafka, G.J.; Kozma, A. The construct validity of Ryff’s scales of psychological well-being (SPWB) and their relationship to measures of subjective well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2002, 57, 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, P. Happiness by Design: Finding Pleasure and Purpose in Everyday Life; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, J.J. (Ed.) Handbook of Emotion Regulation; Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sanches, P.; Janson, A.; Karpashevich, P.; Nadal, C.; Qu, C.; Daudén Roquet, C.; Umair, M.; Windlin, C.; Doherty, G.; Höök, K. HCI and Affective Health: Taking stock of a decade of studies and charting future research directions. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Petermans, A.; Cain, R. Design for Wellbeing: An Applied Approach; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hekler, E.B.; Klasnja, P.; Froehlich, J.E.; Buman, M.P. Mind the theoretical gap: Interpreting, using, and developing behavioral theory in HCI research. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Paris, France, 27 April–2 May 2013; pp. 3307–3316. [Google Scholar]

- Slovak, P.; Antle, A.N.; Theofanopoulou, N.; Roquet, C.D.; Gross, J.J.; Isbister, K. Designing for emotion regulation interventions: An agenda for HCI theory and research. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2022, 30, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, L.D.; Tugade, M.M.; Morrow, J.; Ahrens, A.H.; Smith, C.A. Vive la Différence; Tugade, M.M., Shiota, M.N., Kirby, L.D., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 241–255. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J.; Kim, C. Positive emodiversity in everyday human-technology interactions and users’ subjective well-being. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2022, 14, 651–666. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L.; Kang, J. Employing Emotion Regulation Strategies in Tracking Personal Fitness Progress. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2018, 35, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schueller, S.M. Behavioral intervention technologies for positive psychology: Introduction to the special issue. J. Posit. Psychol. 2014, 9, 475–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.; Wadley, G.; Webber, S.; Tag, B.; Kostakos, V.; Koval, P.; Gross, J.J. Digital emotion regulation in everyday life. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 29 April–5 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Quoidbach, J.; Mikolajczak, M.; Gross, J.J. Positive interventions: An emotion regulation perspective. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 655–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Li, S.; Hao, Y. Design-mediated positive emotion regulation: The development of an interactive device that supports daily practice of positive mental time traveling. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2021, 38, 432–446. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, D.; Calvo, R.A.; Ryan, R.M. Designing for motivation, engagement and wellbeing in digital experience. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 300159. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, L.; Kirzinger, A.; Sparks, G.; Stokes, M.; Brodie, M. KFF/CNN Mental Health In America Survey—Findings—10015. Available online: https://www.kff.org/report-section/kff-cnn-mental-health-in-america-survey-findings (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Israelashvili, J. More Positive Emotions During the COVID-19 Pandemic Are Associated With Better Resilience, Especially for Those Experiencing More Negative Emotions. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1635. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.; Yoon, J.; Kim, C. Mitigating negative emotions in anxious attachment through an interactive device. Int. J. Des. 2024, 18, 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, T.; Vastenburg, M.H.; Keyson, D.V. Designing to support social connectedness: The case of SnowGlobe. Int. J. Des. 2011, 5, 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Desmet, P.M.A.; Sääksjärvi, M.C. Form matters: Design creativity in positive psychological interventions. Psychol. Well-Being 2016, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassenzahl, M.; Eckoldt, K.; Diefenbach, S.; Laschke, M.; Lenz, E.; Kim, J. Designing moments of meaning and pleasure. Int. J. Des. 2013, 7, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Casais, M.; Mugge, R.; Desmet, P. Objects with symbolic meaning: 16 directions to inspire design for well-being. J. Des. Res. 2018, 16, 247–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maréchal, G. Autoethnography. In Encyclopedia of Case Study Research 2; Mills, A., Eurepos, G., Wiebe, E., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2010; pp. 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, H.; Desmet, P.; Yoon, J. On the cultivation of designers’ emotional connoisseurship (Part 1): A theoretical positioning. She Ji J. Des. Econ. Innov. 2024, 10, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Desmet, P.M.A. Researcher introspection for experience- driven design research. Des. Stud. 2019, 63, 37–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.; Bardzell, S.; Neustaedter, C.; Tatar, D.; Lucero, A.; Desjardins, A.; Neustaedter, C.; Höök, K.; Hassenzahl, M.; Cecchinato, M.E. A Sample of One: First-Person Research Methods in HCI. In Proceedings of the Companion Publication of the 2019 on Designing Interactive Systems Conference 2019 Companion, San Diego, CA, USA, 23–28 June 2019; pp. 385–388. [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins, A.; Tomico, O.; Lucero, A.; Cecchinato, M.E.; Neustaedter, C. Introduction to the Special Issue on First-Person Methods in HCI. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2021, 28, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero, A. Living without a mobile phone: An autoethnography. In Proceedings of the 2018 Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Hong Kong, China, 9–13 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, W.-C.; Hassenzahl, M.; Welge, J. Sharing a robotic pet as a maintenance strategy for romantic couples in long-distance relationships. An autobiographical design exploration. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lockton, D.; Zea-Wolfson, T.; Chou, J.; Song, Y.; Ryan, E.; Walsh, C. Sleep ecologies: Tools for snoozy autoethnography. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 6–10 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, W.-C.; Hassenzahl, M. Technology-mediated relationship maintenance in romantic long-distance relationships: An autoethnographical research through design. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2020, 35, 240–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuthel, J.M.; Hofer, L.; Fuchsberger, V. Exploring Remote communication through design interventions: Material and bodily considerations. In Proceedings of the Nordic Human-Computer Interaction Conference, Aarhus, Denmark, 8–12 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- O’Kane, A.A.; Rogers, Y.; Blandford, A.E. Gaining empathy for non-routine mobile device use through autoethnography. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April–1 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Neustaedter, C.; Sengers, P. Autobiographical design in HCI research: Designing and learning through use-it-yourself. In Proceedings of the Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 11–15 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Neustaedter, C.; Judge, T.K.; Sengers, P. Autobiographical design in the home. Stud. Des. Technol. Domest. Life Lessons Home 2014, 135, 135–158. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, J.; Forlizzi, J.; Evenson, S. Research Through Design as a Method for Interaction Design Research in HCI; ACM: San Jose, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gaver, W.; Gaver, F. Living with light touch: An autoethnography of a simple communication device in long-term use. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 23–28 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gamboa, M. Living with drones, robots, and young children: Informing research through design with autoethnography. In Proceedings of the Nordic Human-Computer Interaction Conference, Aarhus, Denmark, 8–12 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Löwgren, J. Annotated portfolios and other forms of intermediate-level knowledge. Interactions 2013, 20, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaver, B.; Bowers, J. Annotated portfolios. Interactions 2012, 19, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, D.; Proudfoot, J.; Clarke, J.; Christensen, H. e-CBT (myCompass), antidepressant medication, and face-to-face psychological treatment for depression in Australia: A cost-effectiveness comparison. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, D.A.; Caldeira, C.; Figueiredo, M.C.; Lu, X.; Silva, L.M.; Williams, L.; Lee, J.H.; Li, Q.; Ahuja, S.; Chen, Q. Mapping and taking stock of the personal informatics literature. In Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies 2020, Online, 12–17 September 2020; Volume 4, pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mandryk, R.L.; Dielschneider, S.; Kalyn, M.R.; Bertram, C.P.; Gaetz, M.; Doucette, A.; Taylor, B.A.; Orr, A.P.; Keiver, K. Games as neurofeedback training for children with FASD. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, New York, NY, USA, 24–27 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, W. The Design of Implicit Interactions; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Buchenau, M.; Suri, J.F. Experience prototyping. In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques, New York, NY, USA, 17–19 August 2000; pp. 424–433. [Google Scholar]

- Buxton, B. Sketching User Experiences: Getting the Design Right and the Right Design; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010; p. 448. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J.; Faulk, J. Design for positive emotion regulation: Introducing the typology of 25 activity-oriented techniques that uplift the well-being of users. Int. J. Des. 2025; in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Doré, B.P.; Silvers, J.A.; Ochsner, K.N. Toward a Personalized Science of Emotion Regulation. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2016, 10, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahrous, A.; Dewidar, K.; Refaat, M.; Nessim, A. The impact of biophilic attributes on university students level of Satisfaction: Using virtual reality simulation. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hommes, J.; Kipp, M. Light Bridge: Improving social connectedness through ambient spatial interaction. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark, 1–5 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Höök, K.; Caramiaux, B.; Erkut, C.; Forlizzi, J.; Hajinejad, N.; Haller, M.; Hummels, C.; Isbister, K.; Jonsson, M.; Khut, G. Embracing first-person perspectives in soma-based design. Informatics 2018, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfarr, N.; Gregory, J. Cognitive Biases and Design Research: Using insights from behavioral economics and cognitive psychology to re-evaluate design research methods. In Proceedings of the Design and Complexity—DRS International Conference, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–9 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Terzi, P.; Tretter, S.; Uhde, A.; Hassenzahl, M.; Diefenbach, S. Technology-mediated experiences and social context: Relevant needs in private vs. public interaction and the importance of others for positive affect. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 718315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. Positive emotions broaden and build. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; Volume 47, pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Boon, B.; Rozendaal, M.C.; Van den Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M.; van der Net, J.; van Grotel, M.; Stappers, P.J. Design strategies for promoting young children’s physical activity: A Playscapes perspective. Int. J. Des. 2020, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S.; Moskowitz, J.T. Positive affect and the other side of coping. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifor, M.; Garcia, P. Gendered by design: A duoethnographic study of personal fitness tracking systems. ACM Trans. Soc. Comput. 2020, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, P.; Cifor, M. Expanding our reflexive toolbox: Collaborative possibilities for examining socio-technical systems using duoethnography. In Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, Paphos, Cyprus, 2–6 September 2019; Volume 3, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, E.E.; McNally, R.J. Exercise as a buffer against difficulties with emotion regulation: A pathway to emotional wellbeing. Behav. Res. Ther. 2018, 109, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklósi, M.; Martos, T.; Szabó, M.; Kocsis-Bogár, K.; Forintos, D. Cognitive emotion regulation and stress: A multiple mediation approach. Transl. Neurosci. 2014, 5, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Troy, A.S.; Shallcross, A.J.; Mauss, I.B. A person-by-situation approach to emotion regulation: Cognitive reappraisal can either help or hurt, depending on the context. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 2505–2514. [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz, J.T.; Jackson, K.L.; Cummings, P.; Addington, E.L.; Freedman, M.E.; Bannon, J.; Lee, C.; Vu, T.H.; Wallia, A.; Hirschhorn, L.R. Feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of a positive emotion regulation intervention to promote resilience for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0305172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PER Technique | Description |

|---|---|

| Being immersed and absorbed | Becoming fully engaged in a positive experience or its aspects, existing only in the present. Example activity: Creating a mural at a school with students, focusing only on the act of painting together. |

| Engaging in a collective | Joining in, or contributing to the shared concerns of a group. Rather than feeling apart from a sense of communal purpose. Example activity: Participating in a marathon to raise money for a sick colleague. |

| Creating a savoring atmosphere | Creating or rearranging the environment to physically, psychologically, and socially support the intended positive experience. Example activity: Lighting candles and playing romantic music during your anniversary dinner. |

| Sharing the positive experience with others | Creating a ripple effect between you and others in response to positive experiences. Example activity: Encouraging your friend to try a terrific new restaurant you discovered. |

| Infusing ordinary events with positive meaning | Enriching day-to-day experiences with language, thoughts, and actions that promote positive associations. Rather than seeing experiences only in a functional way. Example activity: Inventing a nickname for your smart lamp so that you can speak of it playfully. |

| PER Technique | Description |

|---|---|

| Being immersed and absorbed | Bloom fostered sustained engagement by removing external distractions and creating an immersive, uninterrupted experience. The soft lighting and slow transitions helped stay present in the conversation in a calming way. |

| Engaging in a collective | Bloom transformed individual engagement into a shared experience, reinforcing social presence. When multiple people placed their phones on Bloom, the light intensity increased, creating a collaborative interaction ritual—a collective moment of commitment that reinforced the feeling of being part of a group conversation. |

| Creating a savoring atmosphere | Bloom’s lighting and slow, rhythmic feedback encouraged mindful reflection and emotional resonance; the glowing flowers made the space feel more intimate and helped appreciate the conversation more deeply. |

| Sharing the positive experience with others | Bloom functioned as a social cue for positive reinforcement, reminding everyone of their shared experience. Seeing the light respond to their presence reinforced the importance of their conversation, making it feel like a special, collective event. |

| Infusing ordinary events with positive meaning | Bloom elevated casual interactions by giving them symbolic weight. The physical act of placing a phone on Bloom became a ritualistic gesture, reinforcing social accountability and emotional investment. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kozin, K.; Mapara, S.; Kim, C.; Yoon, J. Bloom: Scaffolding Multiple Positive Emotion Regulation Techniques to Enhance Casual Conversations and Promote the Subjective Well-Being of Emerging Adults. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2025, 9, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti9040033

Kozin K, Mapara S, Kim C, Yoon J. Bloom: Scaffolding Multiple Positive Emotion Regulation Techniques to Enhance Casual Conversations and Promote the Subjective Well-Being of Emerging Adults. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction. 2025; 9(4):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti9040033

Chicago/Turabian StyleKozin, Kyra, Sehar Mapara, Chajoong Kim, and JungKyoon Yoon. 2025. "Bloom: Scaffolding Multiple Positive Emotion Regulation Techniques to Enhance Casual Conversations and Promote the Subjective Well-Being of Emerging Adults" Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 9, no. 4: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti9040033

APA StyleKozin, K., Mapara, S., Kim, C., & Yoon, J. (2025). Bloom: Scaffolding Multiple Positive Emotion Regulation Techniques to Enhance Casual Conversations and Promote the Subjective Well-Being of Emerging Adults. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 9(4), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti9040033