1. Introduction

According to Ousley and Cermak (2013), Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition marked by significant impairments in social communication, interaction, and language skills, alongside the presence of restricted and repetitive behaviors, interests, and activities [

1].

Social skills encompass the capacity to engage effectively with others within various social contexts. These abilities include essential behaviors such as cooperation, sharing, turn-taking, and adherence to social norms. Proficiency in social skills enables individuals to successfully navigate group dynamics, resolve conflicts, and collaborate as part of a team. A pivotal element of social competency is empathy, which facilitates understanding and appropriate responses to others’ emotional states. However, a critical caution is that social skills can be misapplied manipulatively, with individuals potentially using these abilities to exploit others. Therefore, grounding these skills in a strong ethical framework is essential to prevent misuse. Research underscores that the early development of social skills is pivotal for sustained interpersonal success throughout life [

2].

Communication skills refer to the ability to transmit information clearly and effectively across verbal, non-verbal, and written channels. Competent communicators not only express their thoughts with clarity but also actively listen to others, fostering mutual understanding and facilitating productive collaboration. Effective communication extends beyond words, encompassing the interpretation of non-verbal signals, such as body language and facial expressions. A potential drawback is that an excessive focus on communication techniques can lead to prioritizing efficiency at the expense of clarity, which may result in misunderstandings. Moreover, overly formal or detached communication can alienate recipients. Striking a balance between precision and empathy is critical. Empirical evidence shows that enhanced communication skills significantly improve interpersonal relationships and professional outcomes [

3].

Emotional skills, commonly referred to as emotional intelligence, involve the ability to perceive, understand, and regulate both one’s own emotions and those of others. These skills equip individuals to manage stress, regulate their emotional responses, and sustain positive social interactions. High emotional intelligence facilitates conflict resolution and enhances resilience in challenging situations. However, it is important to note that individuals with advanced emotional skills may sometimes overly rely on emotional regulation, leading to the suppression of genuine feelings and, potentially, emotional fatigue. Maintaining a balance between effective emotional regulation and authentic emotional expression is vital. According to Goleman [

4], emotional intelligence is a critical determinant of success in both personal and professional spheres, though it must be cultivated alongside other competencies for a well-rounded sense of well-being [

4].

An intervention that can be applied during the early stages of therapy involves the use of social stories. A social story is a short story designed to assist children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in comprehending and navigating social situations, guiding them in appropriate responses. These stories can take written or visual forms, elucidating various social interactions, skills, concepts, and behaviors prevalent in the community. The objective is to provide accurate, compelling, and easily understandable social information tailored to children with ASD. Typically, therapists directly administer social story therapy to autistic children, either through verbal delivery without visual aids or with 2D visual support, although the latter is deemed less precise. The visual aspect’s perceived lack of engagement may hinder the effective conveyance and reception of the story’s intended message [

5].

The visual novel is a genre of game originating from Japan, characterized by narrative storytelling and dialog, which depict its characters and settings. Occasionally, it incorporates gameplay action. Typically, a visual novel presents a branching narrative where the player faces choices that ultimately lead to one of several possible endings. These various branches are often referred to as “routes” or “stories”, concepts related to role-playing games in general. The appeal of these games lies in their replay value, as depending on the game, a different route can lead the player to minor or significant differences from the previous playthrough [

6]. Visual novels are increasingly recognized as tools for education and edutainment.

Most of these games are typically presented as mere learning tools and are not evaluated for their learning outcomes. However, some recent studies have examined and demonstrated the positive effects of educational visual novels on self-efficacy and flow [

7], as well as improvements in knowledge, learning, and interest compared to reading non-interactive material [

8].

Visual novels combine the benefits of games with the narrative and visual presentation of classic books. They can help students improve their language skills, reading and comprehension abilities, and develop imagination and critical thinking [

9].

Virtual reality (VR) technologies have emerged as a powerful and promising educational tool, offering unique features that distinguish them from other Information Communication Technologies (ICT). Virtual reality can be described as a collection of technologies that create highly interactive 3D environments, representing both real and imaginary scenarios. These VR applications can be applied to education thanks to their distinctive attributes that allow users to immerse themselves in a virtual world, interact through multiple sensory channels, and engage with the environment intuitively and in real-time [

10]. It is essential to define virtual reality accurately and ensure its integration into educational programs to maximize its potential benefits.

In contrast to traditional 2D visuals, VR environments offer distinct advantages. Firstly, the immersive nature of VR can enhance the sense of presence and engagement, potentially leading to more meaningful learning experiences. Secondly, the interactive nature of VR, particularly through branching narratives and player agency, promotes active learning. This is particularly beneficial for children with ASD Level 1 as it provides a structured yet flexible environment where they can explore social scenarios, make choices, and observe the consequences of their actions in a risk-free, controlled setting.

With advancements in technology facilitating more digitized learning experiences, the adoption of game-based and immersive educational techniques has increased. This shift aligns with the broader trend of gamifying education, utilizing VR to create engaging, interactive learning modules tailored to different learning needs.

This literature review seeks to explore whether virtual reality social stories—incorporating elements of visual novels such as narrative-driven interactions and decision-making—can effectively aid children with ASD Level 1 in developing social skills. To clearly define the scope of the systematic review and address the pertinent issues, the following research questions have been formulated:

Q1. What are the settings and learning approaches for children with ASD?

Q2. How Virtual reality can improve emotional skills for children with ASD?

Q3. How Virtual reality can improve social skills communication for children with ASD?

A systematic review was undertaken to address the questions. The aim of the systematic review is to evaluate and synthesize existing research on the effectiveness of virtual reality and digital social stories, specifically those that incorporate elements of visual novels—such as narrative-driven interaction and user choices—in supporting social skill development for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. By examining the current body of literature, this review seeks to identify key components, benefits, and limitations of VR social stories in primary educational settings, with a focus on their impact in typical school environments. The ultimate goal is to establish a foundational understanding of how VR-based social stories can be designed to effectively engage and support children with ASD in learning and practicing essential social skills.

2. Materials and Methods

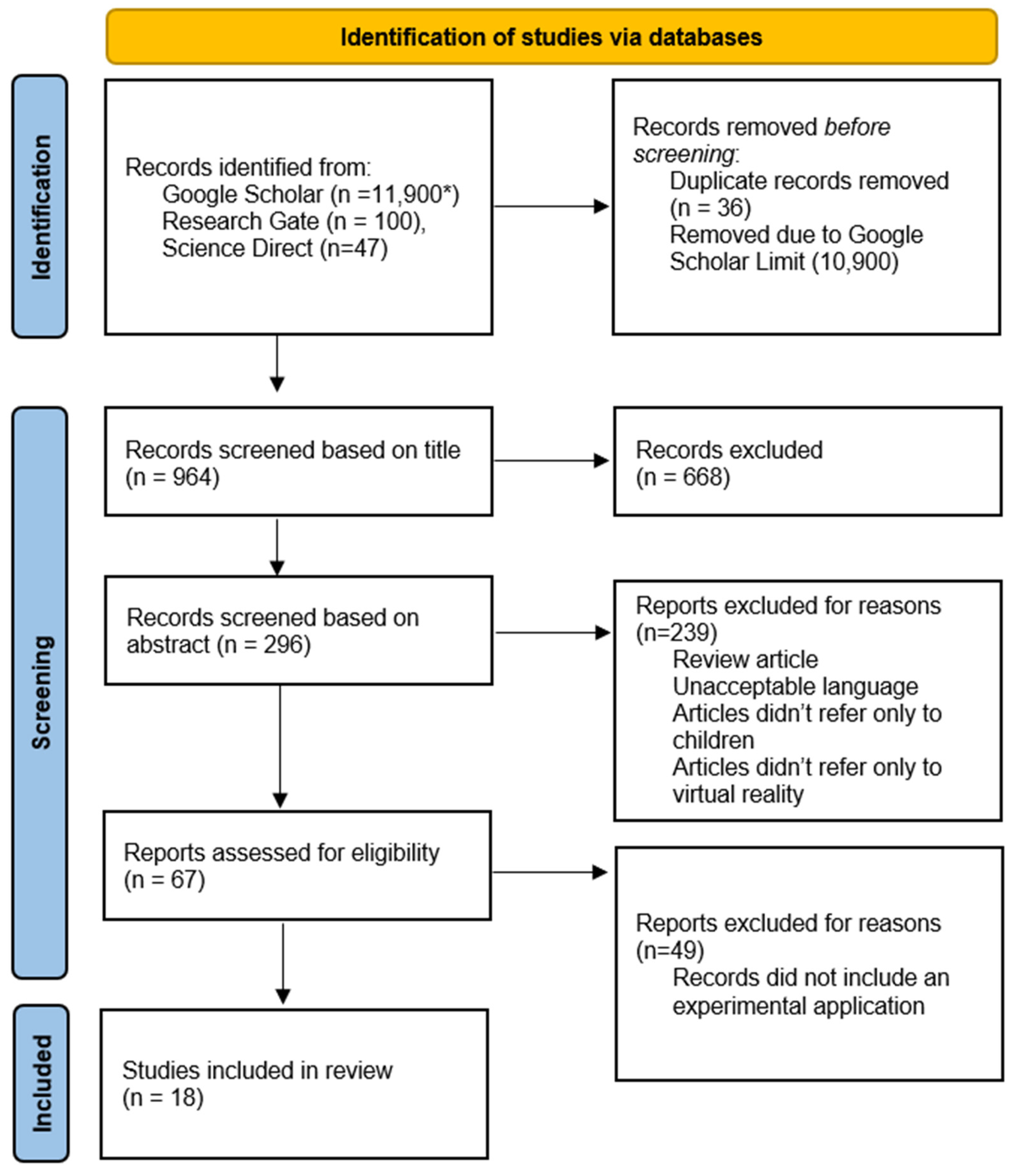

To comprehensively address the research questions, this systematic literature review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

The review included articles published between 2015 and 2024, reflecting the rapid advancements in immersive technologies. Studies were selected based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure the relevance and quality of the data. This approach enabled a focused examination of the effectiveness of virtual reality and digital social stories, specifically those that incorporate elements of visual novels—such as narrative-driven interaction and user choices—in supporting social skill development for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder Level 1.

2.1. Identification of Studies

A comprehensive search strategy was employed across Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, and ResearchGate using Boolean operators and specific keyword combinations: (“Children” OR “Students”) AND (“Autism Spectrum Disorder” OR “ASD”) AND (“VR” OR “Virtual Reality”) AND Education AND (“Social skills” OR “Emotional skills” OR “Communication skills”). Filters were applied to include only studies published between 2015 and 2024, and only peer-reviewed journal articles were considered.

2.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction

According on

Figure 1 a total of 12,047 records were initially identified through database searches. After removing duplicates, 964 unique records remained for title screening. This first screening stage eliminated a large portion of irrelevant studies, reducing the pool to 296 articles for further assessment based on abstracts.

At the abstract screening stage, 239 records were excluded for various reasons, including being non-review articles, inappropriate language, or lack of focus on children or virtual reality, which were essential criteria for this review. Following this, 67 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, with an additional 49 excluded due to not including experimental applications of virtual reality, a key requirement for inclusion.

Ultimately, 18 articles met all eligibility criteria and were included in the final review. This multi-step process, characterized by stringent screening and precise inclusion standards, ensured that only high-quality, relevant studies were selected, thus enhancing the reliability and rigor of the review findings.

The study selection process followed a two-step screening approach. Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts based on predefined inclusion criteria, followed by a full-text review of eligible studies. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus.

Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers using a standardized data extraction form. The extracted information included study characteristics, intervention details, outcome measures, and key findings. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. No automation tools or direct contact with study investigators were used to obtain additional data.

The primary outcomes sought in this review were improvements in social skills, communication abilities, and emotional regulation in children with ASD following VR-based interventions. Secondary outcomes included participant engagement, intervention feasibility, and learning retention. All available results within these domains were collected, prioritizing studies that reported both qualitative and quantitative measures over time. When information was unclear or missing, assumptions were made based on related details within the study, or the study was noted as having incomplete data

Studies were included in the synthesis if they met the predefined eligibility criteria, focusing on VR-based interventions targeting social, communication, and emotional skills in children with ASD. The characteristics of each study, including participant demographics, intervention type, and measured outcomes, were tabulated for comparison. Only studies that provided sufficient data on intervention effectiveness were synthesized, while those lacking outcome details were excluded from the synthesis but noted in the study selection process.

Data from the included studies were systematically tabulated to present key characteristics, intervention details, and outcomes. Tables were used to summarize study settings, participant number, learning approach, and observed effects on social, communication, and emotional skills.

2.3. Bias Assesment

To assess the methodological quality of the included studies, the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist [

11] was used. This checklist evaluates several criteria adequate for each type of study in order to determine the validity, reliability, and overall accuracy of each study. The two authors independently assessed the risk of bias of each included study using this list. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved through discussion and consensus.

4. Discussion

The settings and learning approaches showcase diverse implementations of immersive technology in educational environments, each designed to explore different methods for enhancing learning experiences. In analyzing these studies, several commonalities and distinctions can be observed in how virtual reality systems are used to facilitate both individual and collaborative learning, as well as the environments in which these experiences take place.

The primary objective of this systematic review was to evaluate and summarize the key findings related to the effectiveness of virtual reality programs in the intervention and treatment of children with ASD. A total of fourteen research papers, published between 2015 and 2024, were selected and analyzed for this review.

Several commonalities and distinct differences emerge in the settings and learning approaches used in virtual environments for educational purposes. One notable similarity across most of the studies is that they all take place in controlled, quiet environments, whether in a lab setting [

12,

18] or classrooms [

23] with VR systems [

22]. These quiet spaces are crucial for focusing participants’ attention and reducing external distractions, ensuring that they can fully engage with the virtual environments. One study was conducted in a playroom where participants interacted with peers. However, it is important to mention that, in the end, the researchers had to change the room for one of the participants to complete the sessions [

29]. Additionally, the majority of the studies focused on individual learning experiences, where participants interacted with virtual characters, avatars, or objects on their own, such as in the work of Cheng et al. [

20], Zhao et al. [

24], Moon [

26], Uzuegbunam [

29], Cheng [

20], Beach and Wendt [

19], and Yuan and Ip [

16].

A key difference is found in Parsons [

21], which stands out as the only study that incorporated pair collaboration as a learning approach, allowing participants to engage in collaborative exploration in the virtual environment. This contrasts with the rest of the studies where participants typically entered the virtual environments alone, suggesting that collaborative virtual learning is still relatively underexplored compared to individual learning in these environments.

Another common approach across several studies is experiential learning through interaction with avatars or virtual scenarios. For instance, two studies by Ip et al. [

13,

14] used the CAVE™ VR system, focusing on immersive, scenario-based experiential learning. Similarly, Bekele et al. [

16], Soltiyeva et al. [

25], and Yuan and Ip [

16] provided participants, particularly children with ASD, opportunities for social interaction and exploration within virtual environments, all by using different platforms. However, Zhao et al. [

24] and Frolli et al. [

12] relied more on observation of virtual scenarios rather than direct interaction, which points to a division in how engagement with virtual content is structured—either passively (through observation) or actively (through exploration and interaction).

The length of intervention also varied significantly among the studies. Frolli et al. [

12] and George et al. [

27] implemented relatively long interventions (3 months), whereas other studies, such as Cheng et al. [

17], Didehbani et al. [

18], Vahabzadeh et al. [

23], and Alvarado et al. [

15] had much shorter durations of 5 to 6 weeks and even less. This variation in duration may influence the depth of learning or social skills development that participants can achieve, with longer interventions potentially offering more opportunities for sustained improvement.

Based on Alvarado et al.’s [

15] and Manju et al.’s [

28] studies, it is also important to mention that both studies did not yield the positive results they had anticipated. Both studies pointed out that one potential reason for this outcome could be the limited duration of the sessions. Manju et al. and Alvarado et al. suggested that with more time and additional repetitions, the results might have been more favorable. The limited session time likely restricted the participants’ ability to fully engage and learn, hindering the potential benefits of the interventions. While both studies did find some improvement in general areas, such as social interaction and academic engagement, these improvements were not as substantial as expected. With longer sessions, participants might have had more opportunities for consistent practice and deeper immersion, leading to more significant progress in their social, academic, and psychological development. Therefore, it is crucial to consider that extended exposure and repetition in these virtual environments could potentially yield better outcomes for students with autism.

Regarding areas of intervention, and considering the possibilities offered by VR technologies, most of the studies focused on enhancing communication, particularly social and emotional skills.

The analysis of the reviewed studies underscores the emphasis on social skills interventions for children with ASD, with virtual reality emerging as a significant tool. Social skills, often a core deficit in ASD, were the primary focus in many studies, utilizing avatars and virtual environments to replicate realistic social interactions. This seems to occur because these virtual settings provide a personalized, controlled, and safe space for children to practice and develop these essential skills. This aligns with the literature, as interventions addressing social skill deficits are crucial in ASD therapy [

12,

13,

14,

18,

20,

21,

24,

26,

27].

A notable finding is that studies using virtual platforms, such as “Second Life”, demonstrated improvements in emotional regulation, social attribution, and analogical reasoning [

18,

20,

22,

26]. This is consistent with the literature [

18,

26], as such platforms provide a dynamic method for simulating complex social scenarios that individuals with ASD might otherwise struggle to encounter in real-world settings. These interventions also contributed to enhancing key social skills, including initiating play, responding to social cues, and engaging in conversations, which are essential for improving everyday social interactions. According to the findings of George et al. [

27], the intervention group experienced high levels of presence, perceived realism, and emotional response, as well as overall satisfaction with the VR experience, indicating that the safe, controlled environment of VR played a key role in achieving these positive results.

On the other hand, as emphasized in the research by Soltiyeva et al. [

25], children with ASD tended to focus more on static objects than on dynamic ones, offering valuable insight into their strong attention to detail. This observation aligns with the understanding that children on the autism spectrum often exhibit a heightened interest in specific visual aspects of their surroundings. While interactions with virtual characters are essential for nurturing social skills, some participants faced challenges in fully engaging with these scenarios. For instance, the “Greeting task” with the virtual farmer presented difficulties, as many children required additional time and guidance from specialists to respond appropriately.

Interestingly, while a few children with typical language abilities expressed enthusiasm in playing games, such as “rock-paper-scissors” with a virtual character, indicating the potential for virtual environments to promote positive social interactions, this level of engagement was not consistent across the group. The virtual farm setting was generally well-received, with many children enjoying the opportunity to observe and interact with the animals, suggesting that familiar and engaging settings can promote interest and involvement. However, the mixed success in social interactions highlights the need for personalized support, as not all children responded equally to the social tasks presented during the training. This underscores the importance of individualized approaches in virtual reality-based learning environments for children with autism.

Furthermore, communication skills, another significant challenge for children with ASD, were shown to improve through VR interventions. The analyzed studies indicated positive outcomes in both verbal and non-verbal communication strategies [

12,

13,

14,

17,

21,

22,

24,

26]. As emphasized by Moon [

26], participants exhibited greater confidence in initiating conversations with NPCs in different social scenarios, with some showcasing humor and assertiveness during group discussions. Verbal prompts effectively guided their responses to NPC behaviors, encouraging more appropriate engagement. Additionally, the participants’ varying interests and levels of verbal literacy likely influenced their understanding of the training’s verbal and social cues. This is consistent with the literature because communication forms the foundation of social interaction, and VR provides children with a risk-free environment in which they can practice and refine these skills in a manner that can be adapted to their specific needs. According to Yuan and Ip’s study [

16], numerous parents observed that their children showed greater initiative in greeting and interacting with neighbors and relatives. Additionally, teachers reported that students started forming new friendships and participating in more two-way conversations. Beach and Wendt’s [

19] study showed improvement in participants’ weaknesses. The one participant maintained conversations without redirecting to personal interests and disengaged appropriately from negative interactions. The other sustained eye contact in virtual and real-life scenarios. Both reported feeling less stressed and distracted in conversations after practicing in the immersive virtual environment.

Emotional interventions were also a central focus, targeting the regulation of emotional expression, recognition, and social–emotional reciprocity. This seems to occur because these interventions offer a structured environment where children can learn to identify and express emotions appropriately. Studies revealed that VR scenarios facilitating emotional training showed promising results, improving emotional recognition and competencies related to social-emotional exchanges [

13,

22,

26]. This aligns with existing research, which highlights the importance of enhancing emotional intelligence in individuals with ASD to achieve better social engagement and relationships.

Finally, VR’s unique ability to simulate real-life scenarios, and even those that are otherwise difficult or impossible to experience, presents distinct advantages. By immersing children in these virtual settings, they are able to practice social navigation and emotional recognition in environments that are both challenging and engaging [

21,

24,

26]. This innovative approach shows the potential for VR interventions to significantly improve social competencies in children with ASD, equipping them with vital tools to apply in real-world social situations.

Key Factors Influencing the Effectiveness of VR Social Stories

A closer examination of the included studies reveals several critical factors that influence the success of VR-based social stories in improving social, communication, and emotional skills in children with ASD.

Interactivity and active participation. A deeper analysis of the included studies reveals that the degree of interactivity within VR social stories plays a pivotal role in determining their impact on social, communicative, and emotional development. Studies that featured immersive, scenario-based decision making and dynamic interaction, such as Didehbani et al. [

18], Moon [

26], and Parsons [

21], demonstrated more substantial improvements in participants’ ability to initiate conversations, interpret social cues, and engage emotionally. In contrast, studies like Frolli et al. [

12] and Zhao et al. [

24], which primarily emphasized passive observation of pre-scripted VR scenarios without user-driven interaction, showed more modest improvements in active social engagement. In these cases, children often required additional support to respond to the social content, highlighting the importance of active participation and role-play in achieving meaningful outcomes.

Duration and Repetition. Intervention length and repetition frequency also influenced outcomes. Longer-term programs, such as those conducted by Frolli et al. [

12], George et al. [

27], and Ip et al. [

13,

14], were associated with greater improvements in participants’ ability to initiate and sustain social interactions. In contrast, short-duration interventions like those by Alvarado et al. [

15] and Manju et al. [

28] produced more modest or inconsistent results, often attributing limited success to insufficient session time. These findings support the view that VR interventions may require sustained and repeated exposure to facilitate lasting behavioral change.

Learning Context and Environment. The setting in which the intervention was delivered played a nuanced role. Structured environments—such as laboratories and classrooms used in studies like Ip et al. [

13] and Lorenzo et al. [

22]—helped maintain focus and minimize distraction, which are crucial for children with ASD. However, immersive and emotionally engaging settings, such as the virtual farm used by Soltiyeva et al. [

25] or the playful modules in Vahabzadeh et al. [

23], enhanced participant enjoyment and comfort. This suggests a potential benefit in blending structure with emotionally resonant environments to improve both attentiveness and motivation.

Emotional Engagement and Realism. Finally, emotional presence and perceived realism significantly influenced intervention outcomes. George et al. [

27], Parsons [

21], and Yuan and Ip [

16] noted that emotionally immersive scenarios led to deeper engagement and stronger emotional learning. Children responded more appropriately to social cues and demonstrated empathy when they felt a sense of presence in the virtual world. Conversely, studies like Soltiyeva et al. [

25] reported that some participants focused more on static visual details than dynamic interactions, indicating a need for careful design to ensure that VR environments support—not distract from—emotional and social development.

Despite the promising findings, several limitations were identified in the evidence included in this review. In particular most of the papers focused on children with high-functioning autism, meaning the results may not generalize to all children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Additionally, the evidence supporting the efficacy of VR-based treatments remains limited, as many studies lacked control groups with ASD participants undergoing traditional therapies for comparison. Another limitation is that the majority of the participants were male. Furthermore, the use of new technologies in autism treatment presents challenges, with VR-based interventions still being refined and their effectiveness not yet fully established. Another important aspect is the application of these interventions from home, combined with caregiver training, which could enhance the learning gained during therapy and improve patient–caregiver interactions. This approach could also alleviate caregiver stress and overload.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review highlights the transformative potential of virtual reality (VR) as an innovative intervention tool to enhance social, communication, and emotional skills in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Level 1. By analyzing 14 studies published between 2015 and 2024, this review evaluates the effectiveness of VR interventions, specifically social stories incorporating visual novel elements like narrative and choices, in addressing core developmental challenges in children with ASD.

Findings reveal that VR-based interventions are typically conducted in controlled, quiet environments to reduce distractions and increase engagement. Individualized learning approaches dominate the field, with participants interacting directly with virtual characters, avatars, and scenarios to practice social and emotional skills. Collaborative learning, while explored in only one study, presents an untapped potential to further enrich peer-to-peer interactions in virtual settings. The review also underscores the role of immersive, scenario-based experiential learning in enabling children to navigate realistic social situations, fostering improvements in emotional regulation, empathy, and communication skills.

VR’s ability to provide a safe, structured, and adaptive environment allows children with ASD to practice key social competencies without the pressures of real-world interactions. Many studies reported significant progress in participants’ abilities to initiate and respond to social cues, express emotions, and engage in conversations. However, variations in intervention duration, participant demographics, and methodologies highlight the need for more standardized and inclusive research.

Despite its promise, current VR interventions focus largely on high-functioning children with ASD, limiting generalizability across the spectrum. Challenges such as limited caregiver involvement, inconsistent comparisons with traditional therapies, and underrepresentation of diverse populations highlight areas for future research. Expanding participant diversity, incorporating collaborative VR learning, integrating home-based interventions, and involving caregivers are crucial steps to enhance the impact and applicability of these technologies.

By addressing these gaps and leveraging VR’s unique capabilities, future research can refine VR social stories into scalable, effective tools for helping children with ASD develop vital social and emotional skills, ultimately improving their quality of life and real-world social functioning.

The findings of this systematic review suggest that VR-based interventions hold significant potential for improving social, communication, and emotional skills in children with ASD. From a practical standpoint, educators and therapists can integrate VR social stories and interactive environments into individualized learning plans to provide a safe and engaging way for children to practice social interactions. Policymakers should consider funding and supporting research into scalable VR interventions, ensuring accessibility for children across diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. Future research should focus on standardizing assessment methods, conducting long-term studies to evaluate the sustained impact of VR interventions, and expanding the inclusion of children with varying levels of ASD severity. Additionally, incorporating parent and caregiver involvement in VR-based training could enhance the effectiveness and real-world applicability of these interventions.

Limitations and Future Work

This systematic review has several limitations. The search was conducted in only three databases, excluding well-known databases such as SCOPUS and Web of Science. Additionally, only 1000 of the 11,900 studies were accessible via Google Scholar. Moreover, only journal articles were considered, leaving out conference papers that often contain the latest research. Another limitation is the lack of a specific age limit, aside from the general focus on children. The broad age range and varying participant characteristics across studies introduce variability that may impact the consistency and generalizability of the findings.

Future research should address the limitations of this review by expanding the number of databases used for literature searches, including well-established sources such as SCOPUS, Web of Science, and other comprehensive databases, to ensure a broader and more representative collection of studies. Additionally, incorporating conference papers, which often contain the latest research not yet published in journals, could provide valuable insights into emerging trends and developments.

Another important consideration for future work is the establishment of more specific inclusion criteria, such as defining a narrower age range to allow for clearer comparisons across studies. This would help to better understand developmental differences and ensure more consistent results across various age groups. Moreover, future studies should aim to include a wider spectrum of individuals with autism, encompassing all subtypes and levels of severity, to enhance the generalizability of findings and ensure that interventions are applicable across the diverse autism spectrum.