Abstract

Since the 1960s, atopic dermatitis has seen a steady increase in prevalence in developed countries. Most often, the onset begins at an early age and many patients are very young children. Due to their young age, their parents are forced to take over handling of the disease. As a consequence, atopic dermatitis places a high burden not only on affected children, but also on their parents and siblings, limiting human flourishing of a whole family. Therefore, the described research area calls for a possibility-driven approach that looks beyond mere problem-solving while building on existing support possibilities and creating new ones. This paper presents atopi as a result of such a possibility-driven approach. It incorporates existing patient education and severity scoring into an extensive service, adding new elements to turn necessary practices into joyful experiences, to create feelings of relatedness and to increase perceived self-efficacy, thus is suitable to enable human flourishing.

1. Introduction

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic disease characterized by an inflammation of the skin. In developed countries, it is estimated that every 5th child is affected [1]. Like other chronic diseases, it places a high burden on patients and their families. Its impact on subjective wellbeing and perceived quality of life can even be compared to cancer, diabetes, or a heart attack [2]. So far, approaches center on problem-oriented solutions and show typical characteristics by focusing on minimizing pain and discomfort. As an example, severity scoring in atopic dermatitis enables the documentation of skin conditions, therefore supporting appropriate treatment and contributing to an improvement of symptoms. As Desmet and Pohlmeyer state: “This might make a situation better, but not necessarily good” [3]. Instead, the handling of atopic dermatitis calls not only for the solution of problems, but also for a possibility-driven approach [4] and for positive design to enable human flourishing [3]. In this paper, we discuss and describe an approach to design specifically in the context of chronic diseases, with the intention of providing experiences of self-efficacy [5] and enabling human flourishing through need-fulfilment [6,7], while building on knowledge necessary to manage symptoms of the chronic disease [8].

This paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, we cover basic terminology including chronic disease in general as well as atopic dermatitis in particular, patient self-management, and the characteristics of possibility-driven design and positive design. In Section 3, we describe the design process from research to prototype development, while in Section 4, we introduce the design and results of the user test. In Section 5 and Section 6, we present and discuss the findings.

2. Background

2.1. Chronic Disease

A chronic disease has specific characteristics that are best described by differentiation to acute disease. The latter is characterized by a sudden onset and often foreseeable course. Its process is self-limited or specific therapy is available. Most acute diseases can be diagnosed and named accurately. Treatment with medication or surgery is usually effective. Thus, a cure, followed by return to full health, is likely. Consequently, we can assume low uncertainty in patients. In cases of an acute disease, doctors are proficient, while patients have no special knowledge. In contrast, a chronic disease is commonly characterized by a gradual onset. A long period of uncertainty can pass from first symptoms to an initial diagnosis. As the chronic disease progresses, episodes of severe symptoms can be followed by symptom-free phases. Chronic diseases have no cure and require consistent management over time, forcing the patient to take over treatment and care. In this situation, medical professionals and patients are partially and reciprocally knowledgeable [8].

2.2. Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic disease characterized by an inflammation of the skin. The main symptoms are severe itching and dry, cracked skin [2]. Furthermore, lack of sleep as a result of itching at nighttime is common. The onset of atopic dermatitis is often sudden and leaves patients overwhelmed. An accurate diagnose is difficult and requires time, as episodic recurrence of symptoms at the same time complicate and facilitate assessment. As a result, months of uncertainty can pass from first signs of skin inflammation until final diagnosis. As in many cases of chronic disease, the patient her- or himself takes over responsibility for the treatment of symptoms. Therefore, knowledge about indicated handling is most important, as an appropriate management of symptoms can improve the rash and significantly improve quality of life [2]. Often, first symptoms appear in early childhood, which means many patients are young children [1], with their parents having to take on the management of the disease. The unexpected and unclear entry of atopic dermatitis and consequent burden can leave families feeling helpless and desperate. Dealing with these challenges requires a versatile set of skills, many of which have to be newly acquired.

2.3. Self-Management

Self-management programs emphasize the patient’s central role in managing chronic diseases and support them to live the best possible quality of life with their chronic condition [9]. Self-management aims not only to reduce motivational barriers and the feeling of helplessness by offering information and technical skills; the main objective is to support patients in acquiring problem-solving skills in real-life settings [10]. Patients as well as their social environments should become able to contribute their own preferences and to take responsible actions without supervision by medical professionals. Meta studies investigating the potential of self-management programs support the assumption that these programs are more effective than information-only patient education in improving clinical outcomes [11]. A central concept in self-management is self-efficacy. This concept, originally introduced by Bandura [5], is defined as peoples’ beliefs about their capabilities to produce a behavior that is necessary to reach a desired goal. According to Bandura, four main influences can be distinguished how this subjective confidence of control can be empowered. The most effective way of creating a strong sense of efficacy is through mastery experiences [5], e.g., by finding an appropriate level of challenge that makes success possible and by providing instant feedback on successful outcomes that primarily focuses on the person as an agent. Secondly, self-efficacy can be improved by social models, i.e., by seeing other people similar to oneself who succeeded in reaching comparable goals. A third way is to reduce self-doubts and dwelling on personal deficiencies when problems arise through supporting self-confidence and the belief of having all the resources that are necessary to reach a goal. Finally, self-efficacy is affected by a low level of stress reactions, i.e., the capability to reinterpret burdening factors in the environment. For young children with chronic diseases, it can be assumed that the development of self-efficacy in the context of self-management programs is strongly related to experiences that are centered within the family. Therefore, in this case, self-management programs necessarily have to consider the individual needs of all relevant family members as well as their social interaction, communication, and behavior [12].

2.4. Possibility-Driven Design

Many projects, in whatever context, start by identifying a problem and then proceed to work out a solution to the problem. Such can be called problem-driven design [4]. It can make a situation better, but will not necessarily lead to positive experiences or to human flourishing. In contrast, possibility-driven design seeks to go beyond mere problem-solving, for example by creating meaningful or happy experiences [13]. As a consequence, a possibility-driven approach needs to integrate the fulfilment of human needs like autonomy, competence, and relatedness [3,7,14] (self-determination theory, Ryan and Deci [6]) or strive to increase perceived self-efficacy (self-efficacy theory, Bandura [5]). Another difference lies in the temporal focus of these two approaches: Problem-driven design is rooted in the here and now, focusing on the current, undesirable state. In contrast, possibility-driven design drafts a future state, drawing on potentials [4]: “Problems are obstacles that need to be resolved to achieve a desired goal, objective, or purpose, whereas possibilities are future prospects or potentials” [4].

3. Method and Approach

Positive design [3] states that the intention of design to support human flourishing is decisive [3]. As children are mainly affected by atopic dermatitis, this project is intended to put them at the center of research. Therefore, at the beginning, the intention was set as the following design challenge: How can very young children with atopic dermatitis best be supported in their wellbeing and human flourishing? The project then can be characterized in phases with different aims, during which specific methods were applied. These are as follows:

- Research. Aim: identify research interest. Method: literature analysis.

- Familiarization. Aim: immerse into research context. Method: participating observation.

- Analysis and interpretation. Aim: understand research results. Methods: interview inter pretation, relationship maps, user experience maps, user journey map.

- Design objective and concept. Aim: align with intention to enable human flourishing. Method: matrix.

- Prototype. Aim: enable testing. Method: high-fidelity prototype.

- Evaluation. Aim: evaluate impact. Method: user test, questionnaire.

3.1. Research and Familiarization

In human-centered design, understanding is a necessary starting point. This stage can be described as familiarization, as the designer familiarizes themselves with theoretical knowledge (in this case, medical expressions, symptoms, treatments) as well as practical knowledge (in this case, application of treatment, familial handling of disease). At the very beginning, a basic understanding was created by literature analysis and expert interviews. Drawing from these insights, the main research interests were identified. A five-day stay at a hospital specialized in the treatment of atopic dermatitis was chosen for immersive research combining observation with participation. At the hospital, patients with atopic dermatitis stayed over a longer period of time for an ongoing treatment. The hospital setting offered multiple benefits: the researching designer was embedded in-context, taking part in the same activities as patients and medical staff. The duration of five days allowed deeper immersion as compared to a day-long visit and enabled a deep analysis and understanding. Patients and family members as well as medical staff, nurses, therapists, and nutritionists were available for talks or interviews. Characteristic practices like scratching and application of ointments could be observed in a discreet and respectful manner.

In total, twelve semi-structured interviews with parents were conducted, while children with an average age of 2.4 years were present. Three additional interviews were conducted with hospital staff (head physician, nurse, therapist). Observations were recorded mostly in notes and only few photographs were taken. On every occasion, the researching designer was either introduced by a staff member or introduced herself and the reason for her stay as well as the research interest. All persons interviewed or shadowed were asked for agreement and could withdraw their agreement at any time. In addition, it was made clear that no disadvantage would arise for participants should they decide not to take part. For photographs, explicit consent was asked and pictures taken in a way that faces were not shown. Personal information was treated as strictly anonymous.

3.2. Analysis

Collected material was analyzed using a variety of methods in a specific chronological order, as the results became increasingly fine-grained. All steps support examination of the collected material, enable reflection, and process raw data into interpretable and shareable documents. First, interviews and observations were analyzed for recurring needs and feelings, as well as for characteristic practices (for example, when itching occurs). These were extracted and collected separately in lists. Additionally, interviews were examined in user empathy maps [15] of four individual user types (child, mother, father, medical staff). A user empathy map consists of four quadrants (thinking and feeling, hearing, saying, and doing) and can help to visualize user attitudes and behavior. Building on these findings, two user personas [16] were developed, representing a child and a mother. Both personas were visualized using a portrait and name, substantiated by a photo collage and a short paragraph storytelling the persona’s fictional life. Then, a user journey map [17] was devised, outlining a fictional day in family life including child, mother, father, and sibling. In a last step, correlations were pictured in relationship maps. For a relationship map about requirements and interdependencies between family members, please see Figure 1.

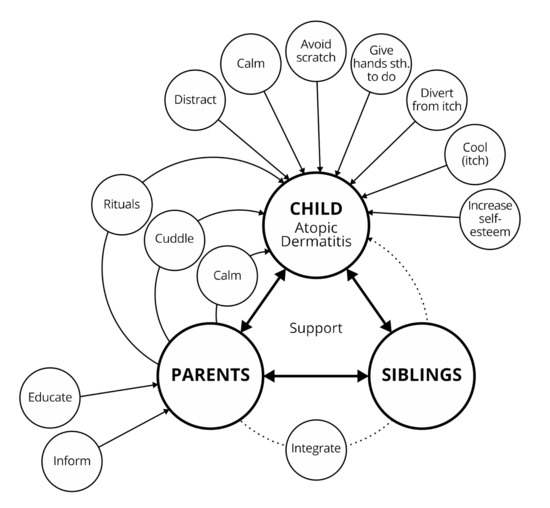

Figure 1.

Results of the user-centered research: Perceived influencing factors of atopic dermatitis symptoms. The lines indicate that a positive effect on children is seen by educating parents, especially when they are primary care providers.

3.3. Interpretation

The results were interpreted keeping in mind the main symptoms of atopic dermatitis, which are itching and inflammation of skin. With regards to itching, it was observed that children use a multitude of strategies, for example using the surface of a couch, a toy animal, or the back of the chair for scratching, or using a metal table leg to cool. Parents are also involved in this process, mainly employing softer methods like soft scratching with the back of the nails or caressing to avoid damaging the skin. Observed and reported scratch alternatives were collected in a list. With regards to inflamed and sensitive skin, appropriate treatment is required several times daily and, as expected, at this age, children are to a high degree dependent from their parents as primary care givers. Interviewed parents spend a considerable amount of time with a multitude of tasks concerning atopic dermatitis, for example caring for their children, playing with their children, distracting them from itching, researching treatment, applying unguent several times a day, visiting doctors, or trying new diets—while beneficial outcomes of this timely investment seem unclear. Consequently, parents reported feelings of strain and helplessness, resulting partially from a lack of knowledge about the nature of atopic dermatitis and appropriate skin treatment. Many complained about difficulties in acquiring reliable information, having more questions that doctors took the time to answer, and slowly and painfully learning through trial and error.

In summary, atopic dermatitis poses many problems that have to be solved in order to improve eczema and other symptoms. Still, we consider it feasible to create a solution that employs a possibility-driven approach. In a study on the potential advantages of divergent hearing, the perspective of “non-normal hearing” (disability) was changed to “divergent hearing” (possibility for enhancement) [18]. While in atopic dermatitis, it is difficult to conceive the main symptoms of eczema or itching as positive, we can take a look at practices that arise from it. Thus, we can change the perspective of necessary treatment from “strenuous duty” to “thoughtful care”. At this point, we want to stress that we have no intention to trivialize the impact of atopic dermatitis, the burden on families, the inflamed eczema, or the painful application of treatment. While keeping all this in mind, we try to take a positive approach to see not only problems but also possibilities. As a chronic disease, atopic dermatitis calls for both the (enhanced) solution of problems and the drafting of possibilities, to enable personal wellbeing. A change of perspective can help to re-script recurring practices typical of atopic dermatitis into joyful experiences. Conclusively, the following requirements for support possibilities were extracted from the material:

(Enhanced) problem-solving:

- Providing information about appropriate handling of the disease;

- Introducing possible treatment options and their advantages and disadvantages;

- Teaching self-management strategies of chronic disease to children and parents;

- Introducing various alternative actions to scratching to break the itch-scratch cycle;

- Underlining the importance of self-care for parents;

- Explaining the relation between “Relaxed parents–relaxed children”;

- Considering an appropriate integration of siblings;

- Relieving parents of wrongly assumed responsibility for the origin of the disease;

- Teaching self-confident handling of public perception of the disease.

Possibility-driven:

- Providing information in a playful way to include all family members;

- Turning itching into a positive practice, creating feelings of self-efficacy;

- Prompting experiences for all family members to foster relatedness.

3.3.1. Atopic Dermatitis and Human Flourishing

Clearly, atopic dermatitis challenges psychological needs of all family members like autonomy, competence, and relatedness [6]. Autonomy can be compromised as the chronic disease dictates everyday life. Competence can be impaired as patients feel helpless in the face of the unexpected course of atopic dermatitis. Lastly, feelings of relatedness between family members can be put under serious pressure. To gain a comprehensive understanding, the findings were arranged in a matrix (see Table 1), starting from a need, then stating characteristic interferences with this need due to the chronic disease, and lastly, filling in possible solutions (problem-solving approach as well as possibility-driven approach).

Table 1.

Atopic dermatitis (AD), conflicts with needs, and intended solutions (problem-solving approach and possibility-driven approach).

3.3.2. Atopic Dermatitis and Perceived Self-Efficacy

At the same time, feelings of self-efficacy (self-efficacy theory, Bandura, 1994) are low, as the patients see little effect of their actions and feel they do not know enough to react appropriately. In the context of arthritis, another chronic disease, it was found that patient self-management and learning about handling of the disease (for example, disease-related problem-solving, medication, and reacting to symptoms and emotions) led to an increase in patient’s confidence to cope with the chronic disease, thus raising perceived self-efficacy [8].

3.3.3. Atopic Dermatitis and Impact on Family Members

In a typical western nuclear family, we can find three affected parties: children with atopic dermatitis, their parents (as caregivers or onlookers), and siblings (who can express feelings of neglect). The complex interplay can be described by the following example: children with atopic dermatitis might take scratching as a way to punish parents or siblings, while siblings in turn might take the opportunity to penalize them by reporting to parents. Parents in turn need to react to both (scratching and reporting) but are under pressure to find the right balance. As every family member can have a positive or negative effect on human flourishing of all others, everyone needs to be considered in a possible solution.

4. Design Objective

Considering these findings, as well as research into self-management in atopic dermatitis [19,20], and taking into account the very young age of the patients, we decided to develop a solution connecting the child, parents, and siblings in a conjoined effort to improve symptoms and quality of life, and thus, enable human flourishing. Focusing on one functionality, like creating a single scratch alternative, seemed unsatisfactory, as it would mean only a small and particular improvement of the disease and—given the individual differences of trigger factors—only few children would benefit. Therefore, after analysis and interpretation of findings, three basic requirements for development of a support possibility were noted:

Three basic requirements:

- Education about atopic dermatitis and appropriate handling;

- Fulfilment of psychological needs (SDT and SET);

- Inclusion of whole family.

4.1. Existing Approaches

In the context of atopic dermatitis, we already find well-developed approaches that focus on patient empowerment. Two main approaches are severity scoring and, as mentioned, patient education. Severity scoring [21,22,23,24] categorizes skin conditions in three stages ranging from no inflammation to highly inflamed, with each stage requiring specific treatment. During the introduction of the SCORAD (Scoring Atopic Dermatitis) index [21], physicians took care of scoring, but over time, the process has been gradually changed into self-assessment by patients [22,23,24]. Recognizing the actual stage and applying appropriate treatment is a prerequisite to improve the skin condition. Therefore, severity scoring can greatly contribute to quality of life.

Patient education in atopic dermatitis integrates severity scoring but covers a multitude of topics. In fact, its aim is to impart all knowledge necessary to enable self-management of the disease by the patient. In Germany, the ArbeitsGemeinschaft NeurodermitisSchulung e.V. (AGNeS) offers patient education programs tailored to different age groups [19,20]. In the case of very young children, a patient education program directed at parents is available. The AGNeS working group consists of specialists in the treatment of atopic dermatitis; the education program is thoroughly developed, based on profound scientific knowledge of atopic dermatitis and psychology, and is well attended. For deeper insight, the researching designer participated in a parent education program consisting of six appointments. Before taking part, the researching designer introduced herself and her research interest to the organizers, as well as to all participating parents. The education program was found to be comprehensive, with appointments being led by experts from different backgrounds. Parents expressed great satisfaction with their learning and the education program, and the knowledge imparted during its course had the potential to increase quality of life. Given the setup as personal meetings, a few drawbacks were noted:

Drawbacks of educational programs as meetings:

- Fixed in time and space, may not reach everyone (too far, no time);

- Usually, one family member takes part—is, therefore, the only knowledgeable one;

- Children are not present during the meetings;

- Apart from flyers or printouts, imparted knowledge has no place or presence at home;

- Knowledge may thus be forgotten;

- Program may come too late;

- Some parents may never learn about them.

We examined these two approaches in terms of a problem-solving or possibility-driven approach and found that they mainly focus on changing the current, undesirable state. PO-SCORAD (Patient Oriented SCORAD) [22] solves the problem of severity scoring by offering a helpful app. In this process, users learn to differentiate skin conditions, essential for appropriate skin treatment. Thus, severity scoring has a great influence on the course of the disease and quality of life. Patient education as offered by AGNeS [19,20] is able to solve a multitude of problems, from appropriate treatment to nutrition to psychological issues, but focuses on problems instead of creating possibilities. Still, the significance of these two approaches in terms of skin improvement cannot be stressed enough. Given the challenges of atopic dermatitis, it is necessary to offer patient education and severity scoring. The proposed service atopi goes one step further.

4.2. Concept

Desmet and Pohlmeyer describe possibility-centered design as entering “the positive space beyond neutrality” [3]. Instead of eliminating pre-existing negative factors, positive design intends to support existing possibilities and to create new ones. In the case of atopic dermatitis, severity scoring and patient education are existing possibilities that have the potential to significantly improve quality of life. With the proposed design, we seek to reach even greater wellbeing by connecting existing elements of problem-driven solutions for atopic dermatitis and drafting new elements based on a possibility-driven approach.

Therefore, we propose atopi as a design solution. atopi is a service for families with very young children just diagnosed with atopic dermatitis. It consists of four boxes containing information about the chronic disease and material to address personal wellbeing. The first box should ideally be handed over by a pediatrician directly after diagnosis. The following boxes are intended to be sent at weekly intervals to the families. The material of the first box includes a brochure, folder, cards, and a cool pad with a sleeve, while digital items in the form of an app and an e-learning tool are linked via QR-codes. The box also provides space for additional material like flyers, if the individual diagnosis requires. This multitude of items provides a choice for the families: Parents who prefer reading might reach for the brochure, parents who prefer videos might watch the video instead. Children might select cool pad “Coolie” for his toy-like appearance or might be drawn to the big illustrations on cards and brochure.

All items are connected by a consistent graphic design that was developed for the service, characterized by clear colors and clean illustrations, with the intention to make a complex subject like atopic dermatitis appear manageable and to appeal to children as well as adults. The layout includes illustrations of relatable characters like Lili (a girl with atopic dermatitis) and Dr. Atopi. The focus lies not on suffering, but on confident, knowledgeable characters. In the following paragraph, all items are explained in more detail with their main purpose.

4.2.1. Brochure, Video, and Folder—Provide Information

The brochure (see Figure A1) and video are the main sources of information and cover the same topics with a weekly focus. They contain illustrations (for children) as well as summarized explanations (for parents). Both items are illustrated in atopi style and contain characters like Lili and Dr. Atopi. Children who are not yet able to read can be integrated by pointing at pictures and telling stories. Next to the brochure and video, a folder (see Figure A3) provides information on the psychological aspects of scratching. Its design is clean and intends to address users who might consider themselves professional or regard colorful designs as too child-like and not serious. The information in the brochure, video, and folder is based on AGNeS patient education, with kind permission, to ensure reliable and valid information during testing of the prototype. These sources of information can lead to a better understanding of atopic dermatitis and therefore, provide feelings of autonomy and competence.

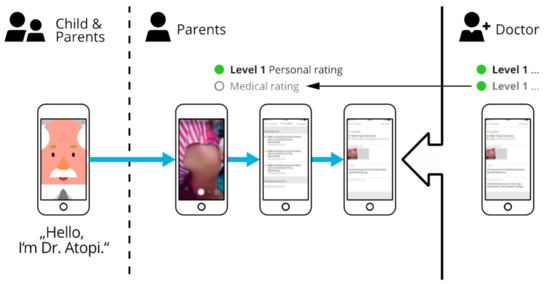

4.2.2. Dr. Atopi—Document Skin Condition

Dr. Atopi (see Figure 2, far left) is integrated into the atopi app that follows the setup of severity scoring like PO-SCORAD [22]. Parents can document skin condition and rate severity to learn to recognize the current stage (see Figure A4). The app is intended to be checked by professionals on a regular basis who give feedback on ratings. Therefore, a day can contain two colors: one is a rating by a parent, the other a rating by a professional (see Figure A3). By comparison, parents can learn appropriate rating. The app prominently features Dr. Atopi who fills up the screen and interacts with children, asking how they are. This is intended to make the recurring process of documentation more enjoyable, to integrate children playfully, and to mediate feelings of relatedness as parent and child communicate with Dr. Atopi.

Figure 2.

Elements of the atopi Box that especially stress the positive approach, from left to right: Dr. Atopi app, fabric expedition card (front and back), and toy-like characters “Sparkle”, “Coolie”, and “Ungi”.

4.2.3. Cards—Create Experiences

Cards (see Figure A2) are designed with a picture on one side (addressing children) and information on the other side (addressing parents). They can fulfil a variety of functions and are categorized as task, scratch alternative, relax, and play and discover. In the prototype, a task card introduces the atopi app. A scratch alternative card explains cool pad “Coolie” and another card features a coloring mandala to distract from itching. Lastly, play and discover cards encourage exchange about topics related to atopic dermatitis. In the prototype, the card suggests a “fabric expedition” (see Figure 2, center) inside the house to examine fabrics (a common trigger factor) and how they are perceived. As a starter, some fabric samples are already included. All participants (children and parents) are put in the same position (as explorers) to encourage free exchange about the effects of atopic dermatitis—a behavior not natural to children. This can empower children by creating feelings of self-efficacy and help to triangulate dialogue about the perception of the disease, which in turn can lead to feelings of relatedness between family members.

4.2.4. Toy-Like Characters—Introduce Scratch Alternatives

The main symptom of atopic dermatitis is severe itching. Often, the itching occurs before inflammation, which is a mere result of skin injuries by scratching [2]. Scratching can even become habitual. During the stay at the hospital, it could be observed that families had developed a variety of personal strategies to distract from itching and avoid scratching. Following AGNeS, these can be classified into four categories:

Categories of scratch alternatives (AGNeS):

- Cooling (cool pad as character “Coolie”);

- Diversion (mandala card);

- Intervention using unguent (unguent container as character “Ungi”);

- Alternative stimulation of skin (massage ball as character “Sparkle”).

For all categories, a scratch alternative has been designed, three of them being toy-like characters (see Figure 2, far right). These scratch alternatives intend to re-script the often unconscious practice into deliberate action by supplying children with a choice of toy-like items. For the first box, cool pad “Coolie” (see Figure A2) has been created. The ears are long to offer a handle and to allow more possible applications, for example using the fabric to scratch often affected areas between fingers. The material is easy to clean and washable; the cool pad can be removed from the sleeve and stored in the freezer. Most importantly, this tool can provide children with a feeling of self-efficacy, as they recognize an immediate effect, and offer an alternative to scratching, thus possibly raising feelings of autonomy. The first box also contains a card with a mandala in the style of a coloring book. While children are busy coloring the mandala, a diversion from the itch is created.

For further boxes, atopi proposes “Ungi” (a character in the form of an unguent pot, explaining the application of unguent and possible usage for cooling an itch) and “Sparkle” (a character in the form of a massage ball, explaining singing and alternative skin stimulation to divert from itching). These three toy-like items could transform daily practices into playful experiences and help to create joy. They are intended to turn itching into a possibility for playful intervention.

4.2.5. E-Learning Tool—Train Situations

An e-learning tool, integrated into the atopi app, can set an additional interactive stimulus. It can be used to prepare for unsettling situations, for example conflict with friends or children’s questions about atopic dermatitis. From the training dialogue, parents can feel better prepared to encounter these situations, and feelings of competence can be raised. This item has not been included in the prototype.

4.2.6. Box—Store and Collect Material

The box (see Figure A1) serves as a container for all the elements and is handed over by the physician directly after diagnosis or sent by post. The unpacking of the box and discovery of its contents reminds families, especially children, of receiving a gift and a sign of appreciation. In this aspect, a desirable design and clear structure is important. The box also serves as a manifested place for all familial knowledge about atopic dermatitis. Additional information and personal objects connected to handling the disease can be added, making the content even more relatable. While some elements might be neglected due to lack of time, toy-like objects have a higher probability to be integrated into daily life and play. They serve as a reminder and connection to the box.

4.3. Prototype

All listed elements (except the e-learning tool) were prepared as prototypes and, in the case of the brochure, cards, and folder, printed. The app was illustrated and animated as a short demo video. For cool pad “Coolie”, a sewing pattern was created and ten sleeves were sewn. An exemplary atopi box, prepared for user testing, can be seen in Figure 3.

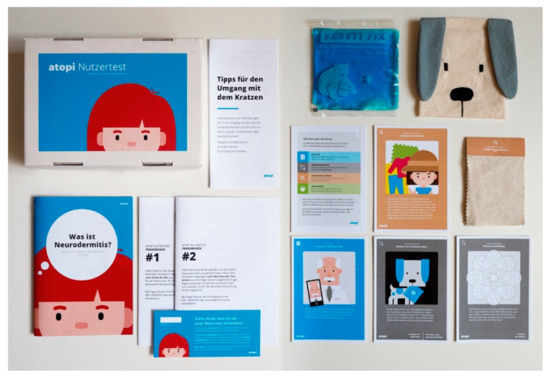

Figure 3.

Prototype, clockwise from top left: box, folder, cool pad and sleeve (Coolie), cards (with additional instruction card), fabric swatches, questionnaires with cover card, and brochure. App and video are not shown.

5. Evaluation

The prototype was used in an evaluation, bringing together expert interviews and user testing. This evaluation served to verify the functionality of the service in a realistic setting and to quickly gain insights.

5.1. Expert Interviews

Two separate interviews with child psychotherapists (one of them specialized in atopic dermatitis) were conducted. Each interview lasted around 45 min. The atopi box and a summarization of interview questions were handed over one day before the interview for testing. After trying the service, the therapists considered it as motivating for children to employ the materials, mainly due to the overall design. When asked what element of the atopi box they were immediately drawn to, both answered “Coolie” as being likeable, tangible, and introducing a scratch alternative. Furthermore, they highlighted the cards which could form a means to triangulate communication between parents and children, and were suitable to break states of helplessness. The full set of cards (comprising different scratch alternatives) could serve as a decision-making tool for children, helping to integrate them in the process of treatment, thus increasing feelings of competence and perceived self-efficacy. During treatment, the atopi box could make knowledge available at home, turning talking at the doctor’s into concrete action. For children aged between 3 and 7 years, old enough to understand their skin was different to their peers, the atopi box could be beneficial by providing information. For very young children, the atopi box could serve as an inspiration for parents. It could also be used to make an abstract condition like a chronic disease easier to grasp and to appear manageable. One expert stressed the importance of hygiene, especially in a hospital context, which would mean wrapping “Coolie” in plastic to make clear it was new and unused.

5.2. User Test

Eight families took part in the user testing. Six of these had been interviewed during their stay at the hospital, where they had expressed interest in a possible user test and had given permission to be contacted. Two more participants were recruited at the patient education. After initial contact, intention and course of the test as well as data protection (anonymization, no publication of personal data, strictly confidential treatment of address) were explained in a text. All participants were informed that they could withdraw at any stage without any consequences.

For the test, all participants received a personal atopi box via post. The box contained all elements, as shown in Figure 3, complemented by a short introduction card, as well as links to video and the Dr. Atopi app. Feedback regarding the box and elements was collected in two questionnaires. The first questionnaire was to be completed directly after receiving the box. The second was to be completed after testing the box and its contents for a week. At the end of questionnaire 2, users also had the opportunity to give open feedback. After the test period, seven families returned the questionnaires using the enclosed return envelopes in time to be considered in the evaluation. These families had children with atopic dermatitis aged between 2 and 7 years. Three children had siblings without atopic dermatitis (age min = 7, max = 13 years), who also took part in the test. In each case, the mother (age min = 32, max = 45 years) served as the main contact person and filled out the questionnaire.

5.2.1. Subjective Overall Ratings of Service

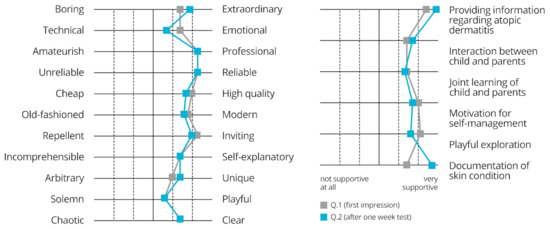

The general impression of the atopi box (entertainment, reliability, quality, educative effect) was evaluated using a semantic differential in both questionnaires: answers before and after using the box for one week were compared. Generally, atopi was rated favorably, with low differences between ratings before and after the test phase (see Figure 4). Furthermore, it was examined if the atopi box supported achieving specific goals (providing information, interaction between child and parents, joint learning, motivation for self-management, playful exploration, and documentation of skin condition). In all aspects, the box was regarded as “supportive” or “very supportive” (see Figure 4). Additionally, all users answered the question “Do you feel better informed about atopic dermatitis” with “Yes”, and all users except one stated they had gained new insights into atopic dermatitis (i.e., psychological aspects, treatment, scratch alternatives).

Figure 4.

Semantic differential for subjective overall rating (left) and rating of perceived support by atopi box (right), n = 7 families, Q.1 = questionnaire 1, Q.2 = questionnaire 2.

The weekly interval of the service (one box per week, total of four boxes) was considered by five users as “very suitable”. Still, four of seven users considered the contents “too much, as an amount that could not be managed in one week”. Open feedback was generally positive, with participants considering the box well designed, providing clear and reliable information. All testers except one considered the mixture between digital and analog material as “not confusing”.

5.2.2. Detailed Ratings of Elements

The second, more detailed questionnaire also recorded grades and frequency of use for all elements. Parents were asked to mark each item with grades between 1 (very good) and 6 (very bad). For children, a smiley-rating (see Figure 5) was included for the cool pad “Coolie”, cards, and brochure.

Figure 5.

Smiley rating for cool pad “Coolie”. As the participating children were mainly very young, the researcher had to rely on feedback from the parents. The visual design of the rating was intended to appeal to children and to remind parents to integrate their view in the questionnaire.

Generally, the items received good to very good grades. The brochure received the best average grade at 1.1. The lowest average grade of 1.9 went to video (low = 3, high = 1) and mandala card (low = 4, high = 1). Frequency of use apparently was not very high during the test period, with a minimum of 1 instance of use and a maximum of 4 instances of use. Parents most often used the brochure (average 2.3 times, min = 1, max = 4), while children most often used cool pad “Coolie” (average 2.6 times, min = 1, max = 4). Concerning the app, all test users, except one, stated to own a smart phone and to use it regularly, with respect to atopic dermatitis i.e., for research, as a calendar (e.g., for medical appointments), and for documentation of the skin condition. When trying the demo app with Dr. Atopi together with their children, parents reported that the children reacted either “interested” or “amused”. Five of seven users stated they would use the app for documentation. Of the two remaining testers, one did not own a smart phone. The other would use the app during acute phases of the disease to identify personal trigger factors, due to the time the documentation would require.

6. Discussion

The intention of the atopi box is (1) to enhance existing, problem-driven solutions for atopic dermatitis; (2) to create new, possibility-driven solutions along unique experiences of children with atopic dermatitis; and (3) to connect these ideas in a service to enable human flourishing of families with very young children with atopic dermatitis.

Two existing and proven approaches, severity scoring and patient education, were redesigned in the atopi box as an app and information materials (brochure, video, folder). This redesign considered an optimistic stance of experience design [4] and re-scripted necessary practices like severity scoring into moments of joy, for example by introducing character “Dr. Atopi” and having him greet and interact with the children in the app, thus turning a mere chore into an entertaining experience. Similarly, brochure and video were redesigned to present knowledge in a way to appeal to the whole family, while at the same time, conveying all needed information, thus enabling all family members together to engage with knowledge about the chronic disease. These aims, covered in the evaluation as items “providing information”, “motivation for self-management”, and “documentation of skin condition” (see Figure 4), received the highest or very high ratings after one week of testing. Based on the open feedback, parents seem to feel more secure in handling the disease and we can assume feelings of competence and self-efficacy.

Furthermore, the atopi box incorporates new, possibility-driven approaches like play and discover cards (fabric expedition) and toy-like items (cool pad “Coolie”). Both take sensations unique to patients with atopic dermatitis, like sensitive skin and itching, and create joyful experiences. In the fabric expedition, families can follow the guidelines on the card and interact with the enclosed fabric samples, or discover fabrics (clothes, furniture) at home. In one test family, a mother reported that her three-year-old son was inspired by the fabric expedition to open up about his personal experiences, which seemed to create relatedness and foster understanding between mother and son. Other parents reported that children played with the swatches but criticized that the fabric samples were too simple and constrained to one purpose.

Cool pad “Coolie” received by far most of the open feedback, invariably positive, with one child reportedly calling out “Can we keep it?” upon first seeing it. Additionally, both interviewed psychologists voted him their favorite, not only due to his looks, but as a means to create feelings of self-efficacy and to overcome felt helplessness. In the evaluation, parents reported that “Coolie” was used both as a scratch alternative and as a toy, in the case of the latter by all siblings (with or without atopic dermatitis). Thus, we can assume that a playful experience and feelings of relatedness were created, while at the same time, a scratch alternative was established that can contribute to improve skin condition, create feelings of self-efficacy, and fulfil needs of autonomy. Additionally, planned toy-like items (unguent container “Ungi”, massage ball “Sparkle”), similarly offering playful scratch alternatives, could further enhance these experiences.

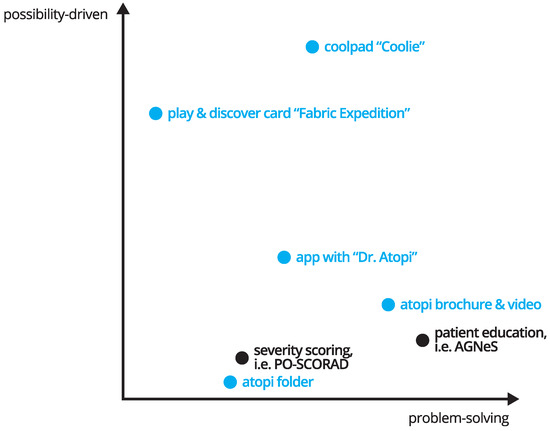

Altogether, the atopi service combines elements with varying degrees of possibility-driven and problem-solving characteristics (see Figure 6) to support coping with atopic dermatitis. The brochure, for instance, might be seen as a pure hygiene factor, offering information about atopic dermatitis. We argue that this item also taps to a certain degree into a possibility-driven approach due to its design. It is meant to transform the process of information into an experience that even small children can feel integrated with. Coolie and the fabric expedition are items that go the furthest above pure problem-solving and draft possibilities. “Coolie”, and the other planned toy-like items “Ungi” and “Sparkle”, take on itch and scratching and turn these moments into playful experiences, while at the same time, offering feelings of self-efficacy. The fabric expedition offers the possibility to explore fabrics with senses unique to children with atopic dermatitis, while at the same time, including all family members.

Figure 6.

Projection of existing approaches and atopi elements along the two axes “problem-solving” and “possibility-driven”. Black = existing approaches, blue = atopi elements. The problem-solving axis does not count the numbers of solved problem, nor does the possibility-driven axis reflect the number of created possibilities. Instead, the diagram is a visualization of the authors’ perception of the potential of the single elements.

Manifestation of the service is the atopi box, where all items are collected and which serves not only as a container, but, according to an interviewed psychologist, can embody a space for gathered knowledge about atopic dermatitis. From this collection, families and children with atopic dermatitis can choose according to their wishes and needs. The service as a whole goes beyond mere problem-solving and includes possibility-driven approaches that turn necessary practices into joyful and motivating experiences. At the same time, feelings of self-efficacy are created and the fulfilment of psychological needs is promoted, thus being suited to enable human flourishing of all family members in families with children with atopic dermatitis.

Due to its modular structure, the atopi service can be extended to accommodate individual needs (i.e., information about food allergies) and leaves behind any one-size-fits-all solution. The distribution over four boxes, one box per week, ensures acceptable portions of information and serves as a weekly reminder. Here, the period could even be stretched to two weeks, as four of seven users considered the amount as too much for one week. As atopic dermatitis is a highly individual disease, the box and its diverse content could be an answer. With its setup as a customizable box, even different language versions would be possible, enabling wellbeing of a multitude of people from different backgrounds. One remaining question is how and when to provide the atopi box to ensure all families are reached. A handover by a pediatrician directly after initial diagnosis seems sensible and would spare much pain and suffering, as one mother put it.

The presented user test employed rapid prototyping to quickly evaluate functionality and perception of the atopi service, while two expert interviews added professional opinion. Need fulfilment and feelings of perceived self-efficacy were estimated favorably by psychologists. Thus, in a next step, validated tests for self-efficacy and self-perception can be carried out with a higher number of participants. Participants should be recruited from diverse backgrounds, for example considering different stages of relatedness between family members, to see how the box is accepted by families with lower and higher cohesion. To evaluate which items lead to an increase in self-efficacy, an AB testing could be devised, providing some families with all materials and some families with less materials. Finally, the evaluation should also monitor skin improvement to measure the effectiveness of patient self-management.

7. Conclusions

This paper presents research into support possibilities for very young children with atopic dermatitis using a possibility-centered approach. As research has shown, atopic dermatitis affects not only children themselves, but their parents and siblings as well. The paper thus proposes the service atopi. Following ideas of positive design, experience design, and design for wellbeing, the service aims one step beyond mere problem solving while at the same time, discarding the one-size-fits-all solutionism by offering the means for personalization. The solution enhances existing problem-driven approaches that are proven to improve the course of the chronic disease, and adds new possibility-driven solutions that consider sensations unique to children with atopic dermatitis.

The extensive concept has been evaluated using a rapid, high-fidelity prototype in expert interviews and a user test. Though the current sample is small (n = 7), general results were rather positive and open questions lead to favorable feedback. By the use of a high-fidelity prototype, and testing the concept with easy-to-create, low-technology elements, the first step of the atopi box presents a promising way to support children with atopic dermatitis and their parents, creating feelings of autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the family and raising perceived self-efficacy to support human flourishing and personal wellbeing.

This paper can help researchers and designers with the development of possibility-driven solutions in the context of a chronic disease that has specific requirements. The suggested solutions demonstrate how existing problem-driven, efficient, and proven solutions can be enhanced using a positive stance, and how new possibility-driven solutions can be created drawing on unique qualities of the chronic disease. Figure 6 tries to visualize that both characteristics (problem-solving and possibility-driven) can be incorporated in an item. The goal should be to keep an open, optimistic mind even in contexts where problems seem at first overwhelming (eczema, recurring episodes of skin condition, loss of control, helplessness, burden on family life) and to create opportunities for joyful experiences [4].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.W.; methodology, V.W., M.M. and S.H.; design and prototype, V.W.; validation, V.W.; formal analysis, V.W.; data curation, V.W.; writing—original draft preparation, V.W., M.M. and B.P.; writing—review and editing, V.W. and B.P.; visualization, V.W.; supervision-interaction design: S.H.; supervision-psychology: M.M.; project administration, V.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all interview partners, as well as all children and families taking part in the user test of the prototype. The first author would like to thank the specialized hospital for the possibility of embedded research and AGNeS (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Neurodermitisschulung e.V.) for the opportunity to use information of the patient education program in the development of atopi prototype, as well as Christine Lehmann for thoughtful feedback on concept and prototype. Furthermore, the authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Atopi Box and brochure.

Figure A2.

Cool pad “Coolie”, cards, and fabric swatches.

Figure A3.

Folder, Dr. Atopi in atopi app, severity-scoring in app.

Figure A4.

Severity rating in atopi app. Parents take a picture of current skin condition and make a rating (for example Stage 1) and receive feedback by a physician, who makes their own rating according to the provided photograph of skin condition.

References

- Flohr, C.; Mann, J. New insights into the epidemiology of childhood atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2014, 69, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ring, J. Neurodermitis: Atopisches Ekzem; Thieme: Stuttgart, Germany, 2012; ISBN 978-3-13-146661-7. [Google Scholar]

- Desmet, P.M.A.; Hassenzahl, M. Towards Happiness: Possibility-Driven Design. In Human-Computer Interaction: The Agency Perspective; Zacarias, M., de Oliveira, J.V., Eds.; Studies in Computational Intelligence: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Desmet, P.M.A.; Pohlmeyer, A.E. Positive Design—An Introduction to Design for Subjective Well-Being. Int. J. Des. 2013, 7, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy. In Encyclopedia of Human Behavior; Ramachaudran, V.S., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassenzahl, M.; Diefenbach, S.; Göritz, A. Needs, affect, and interactive products—Facets of user experience. Interact. Comput. 2010, 22, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, H.; Lorig, K. Patient Self-Management: A Key to Effectiveness and Efficiency in Care of Chronic Disease. Public Health Rep. 2004, 119, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redman, B.K.; Abt-Zegelin, A.; Brock, E. Selbstmanagement Chronisch Kranker: Chronisch Kranke Gekonnt Einschätzen, Informieren, Beraten und Befähigen; Pflegeberatung Patientenedukation; 1. Aufl.; Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2008; ISBN 978-3-456-84503-6. [Google Scholar]

- Seidel, G.; Meierjürgen, A.; Melin, S.; Krug, J.; Dierks, M.-L. (Eds.) Selbstmanagement bei Chronischen Erkrankungen; Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-8452-8991-5. [Google Scholar]

- Warsi, A.; Wang, P.S.; LaValley, M.P.; Avorn, J.; Solomon, D.H. Self-management Education Programs in Chronic Disease: A Systematic Review and Methodological Critique of the Literature. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004, 164, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinquart, M. (Ed.) Wenn Kinder und Jugendliche Körperlich Chronisch Krank Sind; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; ISBN 978-3-642-31276-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hassenzahl, M.; Eckoldt, K.; Diefenbach, S.; Laschke, M.; Lenz, E.; Kim, J. Designing Moments of Meaning and Pleasure. Exp. Des. Happiness 2013, 7, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Hassenzahl, M.; Diefenbach, S. Well-being, need fulfillment, and Experience Design. In Proceedings of the DIS 2012 Workshop on Designing Wellbeing, Newcastle, UK, 11–12 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, B.; Silva, W.; Oliveira, E.; Conte, T. Designing Personas with Empathy Map. In Proceedings of the SEKE 2015, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 6–8 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, A. The Inmates Are Running the Asylum; Sams: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-672-31649-4. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, T. Journey mapping: A brief overview. Commun. Des. Q. 2014, 2, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörrenbächer, J.; Hassenzahl, M. Changing Perspective: A Co-Design Approach to Explore Future Possibilities of Divergent Hearing. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems—CHI ’19, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; ACM Press: Glasgow, UK, 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wenninger, K.; Kehrt, R.; von Rüden, U.; Lehmann, C.; Binder, C.; Wahn, U.; Staab, D. Structured parent education in the management of childhood atopic dermatitis: The Berlin model. Patient Educ. Couns. 2000, 40, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staab, D.; Diepgen, T.L.; Fartasch, M.; Kupfer, J.; Lob-Corzilius, T.; Ring, J.; Scheewe, S.; Scheidt, R.; Schmid-Ott, G.; Schnopp, C.; et al. Age related, structured educational programmes for the management of atopic dermatitis in children and adolescents: Multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2006, 332, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stalder, J.F.; Taieb, A.; Atherton, D.J.; Bieber, P.; Bonifazi, E.; Broberg, A.; Calza, A.; Coleman, R.; De Prost, Y.; Gelmetti, C. Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: The SCORAD index: Consensus report of the european task force on atopic dermatitis. Dermatology 1993, 186, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Stalder, J.-F.; Barbarot, S.; Wollenberg, A.; Holm, E.A.; De Raeve, L.; Seidenari, S.; Oranje, A.; Deleuran, M.; Cambazard, F.; Svensson, A.; et al. Patient-Oriented SCORAD (PO-SCORAD): A new self-assessment scale in atopic dermatitis validated in Europe: PO-SCORAD self-assessment scale validation. Allergy 2011, 66, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolkerstorfer, A.; De van der Spek, F.B.W.; Glazenburg, E.J.; Mulder, P.G.H.; Oranje, A.P. Scoring the severity of atopic dermatitis: Three item severity score as a rough system for daily practice and as a pre-screening tool for studies. Acta Derm. Stock. 1999, 79, 356–359. [Google Scholar]

- Lob-Corzilius, T.; Böer, S.; Scheewe, S.; Wilke, K.; Schon, M.; Schulte im Walde, J.; Diepgen, T.L.; Gieler, U.; Staab, D.; Werfel, T.; et al. The ‘Skin Detective Questionnaire’: A Survey Tool for Self-Assessment of Patients with Atopic Dermatitis. First Results of Its Application. Dermatol. Psychosom. Dermatol. Psychosom. 2004, 5, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).