1. Introduction

In the field of urban and architectural design, “abandoned urban void” is understood as a spatial discontinuity in the urban fabric generated by programmatic abandonment, morphological fragmentation, or socioeconomic crisis. Beyond being a mere physical absence, this notion has been explored as an ambivalent construct: residue, reserve, or resource [

1]. In its densest version, it is recognized as a space with disruptive or innovative potential [

2]. Likewise, Németh and Langhorst [

3] conceptualize these voids as urban lands with multiple possibilities for temporary use or regeneration within a logic of sustainable urban transformation. From an applied and contemporary perspective, Kim, Newman, and Jiang [

4] demonstrate how community engagement with vacant lots in declining cities can activate regenerative processes at various scales.

The scale emerges as a critical variable for analyzing the impact and intervention strategies regarding abandoned urban voids. At the micro- or neighborhood scale, voids manifest as abandoned lots or residual spaces that affect the cohesion and perception of the environment, but whose potential value can be activated through temporary uses or community micro-interventions [

3]; at the intermediate level, unused industrial land, obsolete enclosures, or abandoned rails represent voids whose regeneration requires larger project scales. At the metropolitan scale, voids result from demographic decline or productive reconversion processes [

4]. This article systematizes approaches that encompass these three scales, evaluating how different strategies (from targeted interventions to strategic urban plans) have been applied to activate various types and magnitudes of voids.

Abandoned urban voids are not limited to vacant lots or abandoned buildings; they can also exist in functioning spaces that have lost social, economic, or symbolic significance. Recent studies indicate that these voids include vacant lots, underutilized infrastructure, contaminated lands (brownfields), interstitial spaces, and even operational buildings disconnected from their context [

5,

6].

In this sense, urban regeneration is conceived not only as a physical intervention or architectural rehabilitation but as a comprehensive transformation process that simultaneously addresses morphological, social, cultural, political, and environmental dimensions [

7,

8]. The connection between void and regeneration lies in their dual potential: voids represent spatial dysfunctions, but they also constitute latent opportunities for reactivation, community reinterpretation, and political and cultural innovation.

The study of abandoned urban voids has established itself as a key field for addressing contemporary challenges such as the accelerated expansion of cities, territorial fragmentation, and the environmental crisis. Recent research has shown that these spaces should not be understood solely as degraded areas but rather as potential catalysts for urban and environmental regeneration. Ref. [

9] conducted a systematic review of 55 studies across 14 countries, demonstrating that factors such as landscape connectivity, plot size, and land management influence the ability of abandoned urban voids to support biodiversity and generate ecosystem benefits, although without addressing their architectural reconversion. Complementarily, studies on urban regeneration in European cities like Brescia (Italy) highlight the strategic role of voids in sustainable planning, focusing on reuse policies to avoid land consumption and revitalize the existing urban fabric [

10]. These approaches reveal the transformative potential of abandoned urban voids but also uncover a gap: the limited integration of architectural strategies that convert these spaces into functional and social nodes within the city, which constitutes the core of the research question of this study.

Although the terms “void,” “emptiness,” and “urban gap” share the idea of absences or discontinuities in the urban fabric, it is essential to conceptually distinguish them. The abandoned urban void generally refers to physical spaces without occupation or manifest function, such as vacant lots, abandoned buildings, or brownfields, and it is a recurring category in regeneration studies, as seen in research that maps the causes and effects of vacant areas [

11].

Emptiness, on the other hand, alludes to a sociocultural or functional absence even in spaces that are technically occupied or in use; in this regard, some studies have interpreted emptiness as a condition of symbolic irrelevance or disconnection from the community without necessarily implying physical abandonment, which establishes a distinct conceptual space within urban analysis [

12].

As for the urban gap, it refers to discontinuities in connectivity, flows, or urban proportions (gaps in the spatial or functional network) that do not always imply physical absence but do present obstacles to urban cohesion and mobility. This concept has been discussed in studies that highlight how urban fragmentation can create disconnected, vulnerable, or peripheral areas, even if they are not abandoned [

13].

A recent systematic review evaluated 55 studies published in 14 countries on abandoned urban voids, such as vacant lots and interstitial spaces, and their influence on urban plant biodiversity. Applying the PRISMA protocol, it identified key biological and environmental factors such as lot size, age, soil structure, landscape connectivity, and human management, in contrast to spatial factors like distance to existing green areas. Although this review establishes a solid quantitative ecological foundation, it does not address architectural design strategies aimed at regenerating these voids with urban functionality. Incorporating this aspect clarifies how your research fills that gap in the existing literature [

14].

Additionally, a quantitative study on “interim reuse” mapped 577 abandoned urban voids in the historic districts of Balat and Fener (Istanbul) using a decision model with five variables (ownership, debris, economic activity, surface sealing, and recreational equipment) to classify the spaces, followed by a phase of site-identity-adapted regenerative ecological intervention. This systematic approach integrated machine learning with regenerative treatments but primarily focused on ecological criteria rather than integrated architectural proposals. Comparing this approach with your systematic review highlights the novelty of your study, which combines quantitative models [

15].

Among the less common strategies identified, the rehabilitation of abandoned urban voids is primarily associated with the recovery of abandoned structures and underutilized land in order to reintegrate them into the urban fabric. Studies in European cities indicate that rehabilitation involves not only the physical restoration of deteriorated buildings but also the social and economic reintegration of these spaces. For example, Ref. [

16] analyzes revitalization projects in residential brownfields in the Czech Republic, highlighting that successful rehabilitation combines structural repair with community programs that strengthen neighborhood identity and reduce the perception of insecurity. This approach confirms that rehabilitation of abandoned urban voids cannot be limited to the physical dimension but must integrate social and functional factors to achieve effective regeneration.

In parallel, the remediation of contaminated soils is identified as an essential preliminary step for the reuse of industrial brownfields, which constitute a significant category of abandoned urban voids. Recent research shows that the application of integrated bioventing and phytoremediation systems in contaminated urban lands not only reduces toxic compounds, such as hydrocarbons and heavy metals, but also enables these sites for architectural regeneration projects with low environmental impact [

17]. This type of strategy reveals that remediation should not be considered solely as an isolated environmental process but as a key stage in transforming degraded abandoned urban voids into sustainable urban assets, creating the necessary technical conditions for their conversion into functional and socially beneficial spaces.

Abandoned urban voids should not be designed and viewed as negative elements but rather as spaces with significant potential for urban and architectural regeneration [

14,

15]. These spaces should be developed according to certain guidelines such as connectivity, accessibility, and morphology [

16]. Various intervention strategies have been implemented, including participatory community techniques and co-creative design [

17,

18]. The review found studies conducted in over 20 countries, covering regions such as Europe, Latin America, Asia, North America, and Africa. In these cases, common factors were identified that contribute to the formation of abandoned urban voids, including issues like lack of urban planning or poor urban management [

19,

20].

Urban regeneration presents itself as a key strategy to simultaneously mitigate and improve certain urban spaces that are outdated or excluded in dense areas [

21,

22]. In this context, the change proposed by the authors has been to view abandoned urban voids as strategic opportunities for the optimal development of a city, referred to by Freitas as “new ways to enable them” [

9]. Interventions and nature-based solutions were also highlighted [

23]. On the other hand, no articles belonging to systematic reviews were found; rather, all studies belong to methodological approaches that provide important and usable information for application in this context of abandoned urban voids.

Although the reviewed studies have effectively contributed to the development of urbanism, a paradigmatic shift has yet to occur that would allow these contributions to be expanded to various regional realities, particularly in the South American context. Despite the significant richness provided by critical analyses in the reviewed texts, there are gaps or voids that need to be studied and analyzed, both in territorial and methodological terms. Furthermore, abandoned urban voids should be leveraged and reused, as they hold great potential to become optimal spaces for improving quality of life in cities.

This article aims to analyze the different approaches applied in abandoned urban void interventions and how they seek to address the need to fill these spaces for their rehabilitation or improvement. Through this systematic review, abandoned urban voids will be classified according to certain criteria such as location, origin, and state of use, and their corresponding approaches (adaptive reuse, temporary design, community activation, and green infrastructure) will also be examined. Additionally, the diversity of architectural interventions and the social, ecological, and urban impacts resulting from these modifications will be explored, with the goal of contributing to future research that will benefit the field.

The gaps identified in the specialized literature significantly influence the formulation of the objectives of this research, as they highlight the need to integrate approaches that currently appear fragmented. Most existing systematic reviews address abandoned urban voids from ecological or landscape perspectives, such as the analysis of factors that condition plant biodiversity in urban wastelands [

16], without developing architectural regeneration models that articulate these environmental dynamics with urban functionality. Similarly, quantitative studies [

17] propose ecological treatment guidelines based on classification models of voids but lack a methodological integration that incorporates architectural design strategies aimed at their adaptive reuse. These absences justify that one of the central objectives of this article is to connect the systematic analysis of abandoned urban voids with proposals for architectural and urban regeneration, seeking to build an interdisciplinary framework that transcends the exclusively ecological approach and allows for the treatment of these spaces as nodes of social, functional, and environmental activation within the contemporary city.

2. Materials and Methods

This article aims to scientifically evaluate the integration of abandoned urban voids in urban areas, focusing on how their elements contribute to the resilience of the city, sustainability, adaptability, and the psychological well-being of individuals. The methodology employed is based on a systematic literature review, with the goal of recognizing and assessing the analyzed background on regenerative architecture and urban planning. This methodological approach leads to the following criteria of the PRISMA 2020 framework.

The systematic search in the SCOPUS database identified 80 initial records. After removing duplicates using the Zotero reference manager (n = 0), the titles and abstracts were reviewed to assess the relevance of the studies. From this process, 16 articles met all inclusion criteria and were selected for final analysis following the stages of the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram; it is important to clarify that the total number of 80 records corresponds to the initial population of articles obtained after applying the search strategy, while the 16 articles constitute the final sample used for data extraction and synthesis. This figure aligns with the studies that passed the eligibility phase after the full-text review, ensuring consistency between the stages of identification, screening, and selection.

The question is the following: What strategies and approaches in the current architectural intervention have been utilized for the regeneration of abandoned urban voids within established urban contexts?

The use of the PRISMA 2020 protocol was chosen to ensure the transparency, comprehensiveness, and reproducibility of the systematic review. PRISMA has been recognized as the international methodological standard for synthesizing scientific evidence, allowing for a clear and verifiable structuring of the process of searching, selecting, and analyzing studies [

24]. Its application in urban research has proven effective in integrating multidisciplinary approaches and evaluating complex phenomena involving spatial, social, and environmental variables, as seen in recent reviews on urban regeneration and sustainable planning [

25,

26].

In the context of this study, PRISMA 2020 provided a solid foundation for systematizing the scattered literature on abandoned urban voids and architectural regeneration strategies. The implementation of this protocol allowed for the definition of clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, minimizing selection bias and ensuring that the findings could be comparable and replicable in future research. Furthermore, its graphical structure through the PRISMA flow diagram facilitates the traceability of each stage of the process, from the initial identification of articles to the final selection, which is a key aspect in an emerging field where methodological consolidation is essential.

The inclusion criteria were defined as follows: (A) works published and edited between the years 2000 and 2024; (B) peer-reviewed articles; (C) studies addressing abandoned urban voids and their architectural, urban, or landscape intervention; (D) documents proposing strategies or approaches for urban regeneration; and (E) publications in English, Spanish, or Portuguese. On the other hand, the exclusion criteria that highlight non-viable information are (A) absence of relation to unused or underused spaces, (B) thematic duplication without new contributions, (C) approaches not applicable to the urban context, (D) lack of architectural focus, (E) lack of academic rigor, and (F) regeneration not directed towards the reuse of constructed space.

The search was conducted in an academic database, specifically SCOPUS, which was chosen for its significance in urban studies and for containing research in Spanish, English, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish. A search modality was designed and implemented through the fusion of keywords and Boolean operators considering languages such as Spanish, English, or Portuguese; the applied formula was as follows:

TITLE-ABS-KEY (“vacant lots” OR “vacant land” OR “urban gaps” OR “leftover spaces” OR “derelict sites” OR “underused land” OR “disused urban areas” OR “urban interstices” OR brownfields OR “residual space”) AND ALL (“architectural rehabilitation” OR “architectural renewal” OR “adaptive reuse” OR “building reuse” OR “architectural retrofitting” OR refurbishment)).

The selection of studies was conducted in three stages using the Parsifal program (2025). In the first stage, duplicate requirements were eliminated using the Zotero bibliographic manager. In the second stage, titles and abstracts were examined to verify their relevance, and in the third stage, a thorough reading of the documents was carried out to apply the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Additionally, an extraction sheet was created where the databases, article titles, authors, references, and citations were noted according to APA (American Psychological Association, 2020) 7th edition standards, along with keywords, research problem, general objective, key ideas that assist in problem formulation, reading compilation, results, conclusions, discussion, and contributions related to biophilic design and automation in a resilient environment.

Some biases were implemented in the review, including publication bias (limitation to academic literature), selection bias (inclusion/exclusion criteria), and access bias (relevant studies that may be outside the public domain). No bias statistics were developed as a meta-analytic review was not the goal.

The selection process is presented in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram. A total of 80 initial records were identified, and after removing duplicates (n = 0), 80 titles and abstracts were examined, of which 16 were chosen that met all the criteria and were included in the analysis (see

Figure 1).

Justification for the Use of PRISMA 2020

The choice of the PRISMA 2020 protocol responds to the need to structure a systematic review that ensures transparency, reproducibility, and methodological rigor in an interdisciplinary field like urban studies. Although PRISMA was initially developed for health sciences reviews, its structure, based on the traceability of the search and selection process of literature, has been successfully adapted in urban and territorial research. For example, [

27] applied PRISMA to evaluate urban resilience strategies against climate change, demonstrating its ability to integrate multidisciplinary evidence and synthesize complex findings in urban contexts. Similarly, [

28] used PRISMA to analyze systematic reviews on urban sustainability, confirming that the protocol can be adapted to assess urban phenomena, with methodological rigor comparable to that of other scientific fields.

Additionally, PRISMA 2020 provides a standardized framework that allows for the establishment of clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, minimizes selection biases, and ensures that the results are traceable and replicable. This quality is particularly relevant in the analysis of urban gaps and architectural regeneration strategies, where the literature is scattered and multidisciplinary. Recent studies in Cities and Sustainable Cities and Society demonstrate that adapting PRISMA to urban contexts facilitates the identification of patterns and the construction of integrative conceptual frameworks [

29,

30] (Zhang, G; Longo, A.). For these reasons, the implementation of PRISMA in this study is not assumed automatically but rather as a methodological adaptation grounded in previous experiences documented in literature indexed in SCOPUS.

3. Results

Concluding with the methodology, the selection stages were carried out according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, followed by an analysis of the results obtained, in which 84 articles were identified for study and 16 were selected for their high relevance to the topic. This allows for generating answers to the research questions posed in this article, along with their respective graphs.

3.1. Reference Statistics

3.1.1. General Statistics Reference Statistics

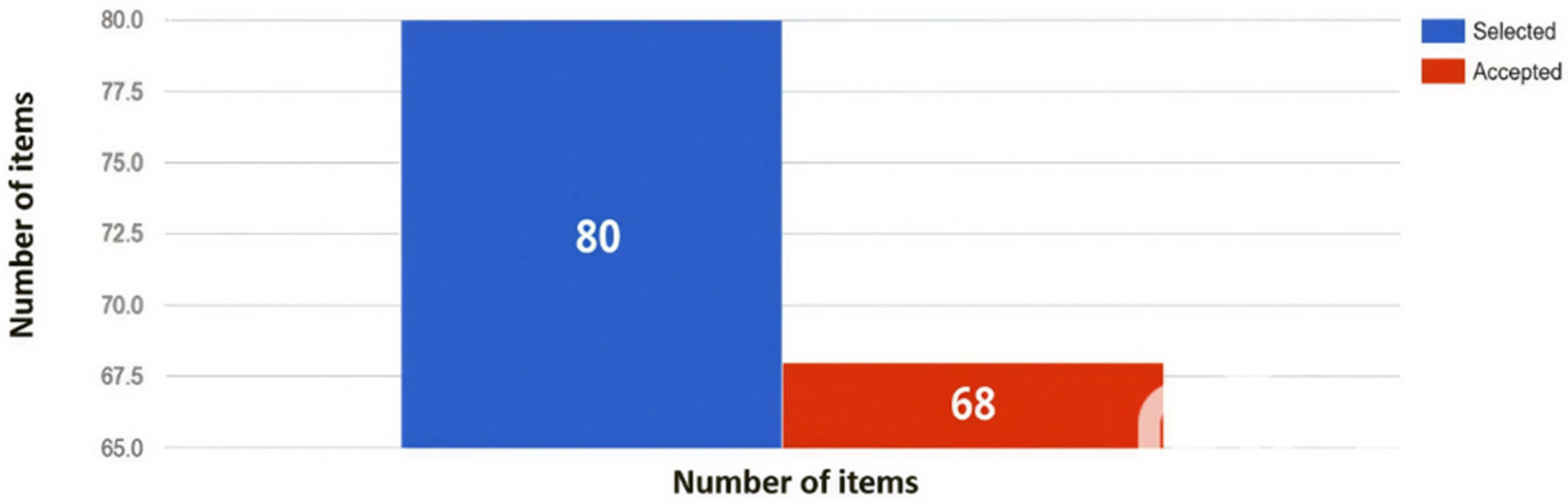

The 80 articles considered in this study come from the Scopus database. This indicates that articles from other sources, such as Web of Science or Scielo, were not included, so all the reviewed studies are concentrated on a single platform, demonstrating a rigorous selection criterion as shown in

Figure 2.

In this graph (

Figure 3), it is evident that, out of approximately 80 articles selected from Scopus, only 68 were accepted after the quality assessment due to the filtering process through the system, where only a tiny percentage meets the final inclusion criteria, ensuring a strict refinement of the content.

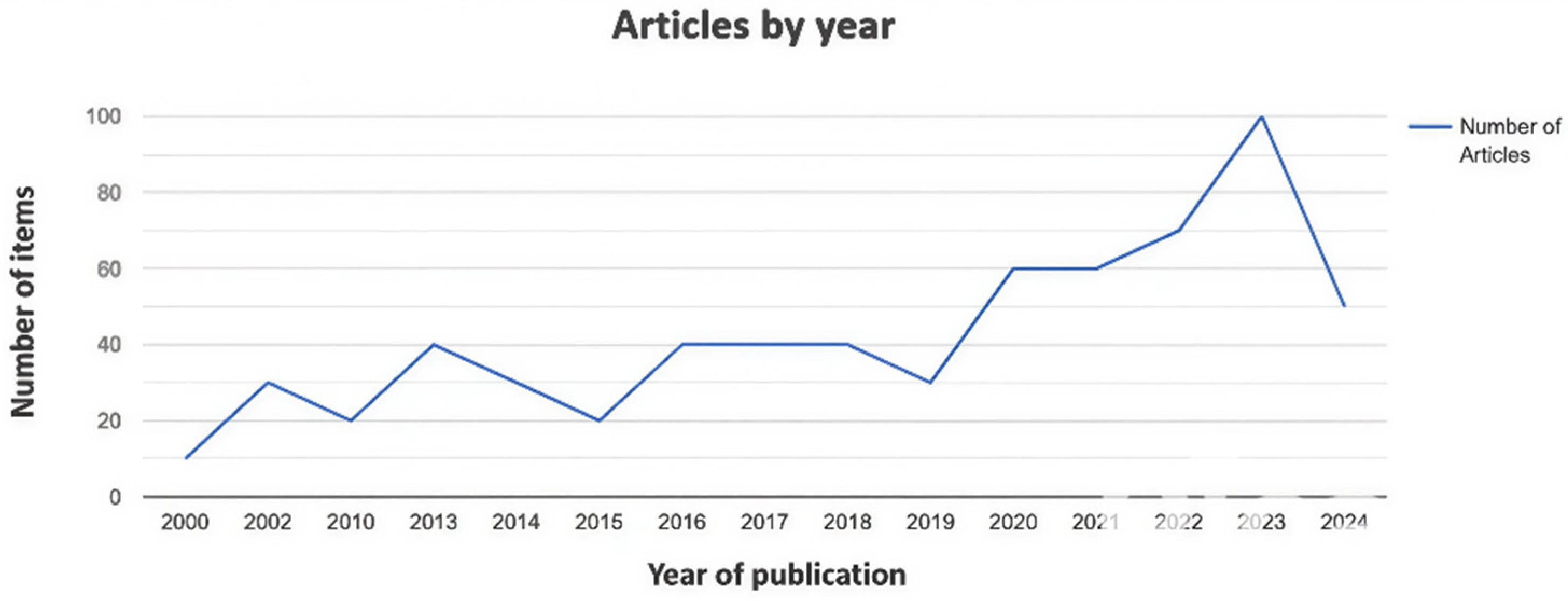

Figure 4 shows an irregular growth in the number of accepted articles from 2000 to 2024, indicating that, from 2000 to 2019, there was a stepped increase, with growth from 2019 to 2023, and in the last year, there was a decrease in the number of published articles. This may suggest a lack of greater interest in publishing new recent articles on the researched topic.

The following table presents information on accepted and peer-reviewed scientific articles within the framework of a study on abandoned urban voids. Each row corresponds to an article, and columns provide data such as title, author(s), year, country, design, population, and main findings. Additionally, it showcases the geographical, methodological, and thematic diversity of the analyzed studies, highlighting approaches such as adaptability, sustainability, integration, innovation, and resource use in spaces, among others.

The type of article in this research is quantitative, and through the study of 16 selected and accepted articles, categories focused on qualitative analysis were identified, allowing for the recognition of various approaches and impacts regarding the proposed strategies (see

Table 1).

3.1.2. Strategies and Intervention Approaches Applied in Abandoned Urban Voids

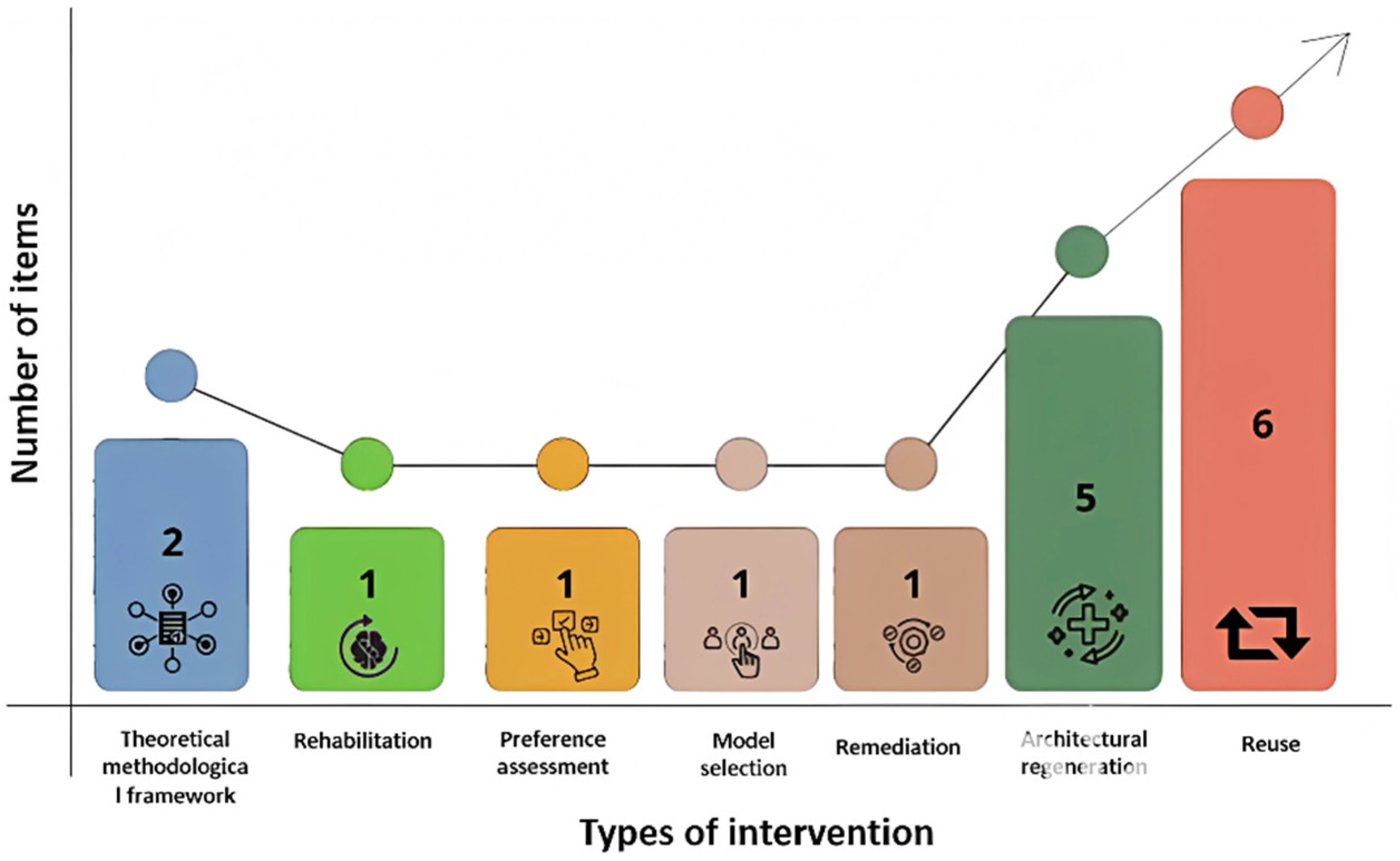

Of the 16 articles analyzed, the most predominant approach is the reuse of abandoned urban voids, present in six articles; secondly, urban regeneration as a strategy appears in five articles. Additionally, one article mentions remediation, another utilizes model selection, one proposes preference evaluation, another mentions rehabilitation, and two focus on the theoretical and methodological framework.

Figure 5 visually represents the distribution of the articles according to the type of intervention proposed. Considering the total of 16 studies, the graph shows that reuse is the most employed strategy, with a total of six studies. This intervention is based on the reuse of disused structures that are being abandoned or rendered unusable, thus exhibiting its main characteristics of efficiency, adaptability, and low environmental impact. Among the authors proposing this approach are [

22] or [

20] or [

27] or [

18] or [

14,

16].

On the other hand, architectural regeneration is found in five studies and is characterized by proposing transformations in deteriorated or vacant spaces. This approach is mainly applied in “brownfields” and degraded industrial areas, integrating principles of landscaping and sustainability. The authors who develop this strategy are [

10,

15,

19,

21,

28].

At the intermediate level, there are theoretical and methodological approaches that do not involve direct physical interventions but focus on conceptual analysis. These studies provide tools and theoretical frameworks applicable to urban planning, constituting a solid foundation for future interventions with greater rigor and academic support.

There are also less common strategies, each represented by a single study, which are rehabilitation, outcome assessment, model selection, and remediation. Rehabilitation involves the recovery of degraded and abandoned structures for inclusion in the urban fabric [

23]. Outcome assessment centers on the perspective of citizens for urban design [

17]. Model selection applies technical foundations to appropriately intervene in spaces [

28], and environmental remediation of contaminated soils serves as a basis for future interventions [

20].

Overall, there is a clear trend toward sustainable and practical interventions, highlighting that the most proposed interventions in this review are reuse and regeneration. It can be seen that current interventions have a greater focus on low environmental impact strategies, and the value of theoretical and participatory approaches is also emphasized as complementary information for making informed and substantiated decisions.

3.1.3. Architectural and Urban Strategies Implemented

Of the 16 articles, it is evident that the most common strategies for intervening in abandoned urban voids are adaptive reuse, focusing on transforming abandoned spaces into new functional uses; architectural regeneration, which applies urban design to revitalize degraded areas; and environmental remediation, aimed at decontaminating industrial soils.

In

Figure 6, adaptive reuse involves transforming abandoned land or buildings for new urban uses, such as parks, housing, agricultural spaces, etc. The most notable case is that of brownfields, with six articles discussing reuse, whether of residual spaces, environmental regeneration, or utilization strategies, among others. The authors include [

22] or [

20] or [

27] or [

18] or [

14,

16].

Architectural regeneration focuses on applying urban design and architecture to revitalize deteriorated areas, with an emphasis on functional, environmental, and social renewal. The authors develop regeneration strategies, comparing abandoned places with regeneration zones and selecting regeneration models. The authors involved in this application are [

15,

21,

28].

Environmental remediation encompasses the processes for soil decontamination and environmental recovery as a preliminary step for new urban and architectural uses, which includes the restoration of contaminated soils, environmental treatments, and the application of the AdRem model in contaminated sites. The authors who conduct these applications are [

20] or [

18,

27].

Landscape design is proposed as an architectural tool to regenerate deteriorating industrial lands [

21]. On the other hand, there is the participatory intervention of the population in the regeneration process, perception, and appropriation of space in urban regeneration projects [

17].

Finally, we have the conceptual / methodological framework that studies theoretical or methodological models to guide interventions in abandoned urban voids from planning and evaluation, based on the urban ecosystem approach and the theoretical determination for green regeneration [

10,

15].

3.1.4. Intervention Strategies and Their Impacts on Sustainable Urban Regeneration

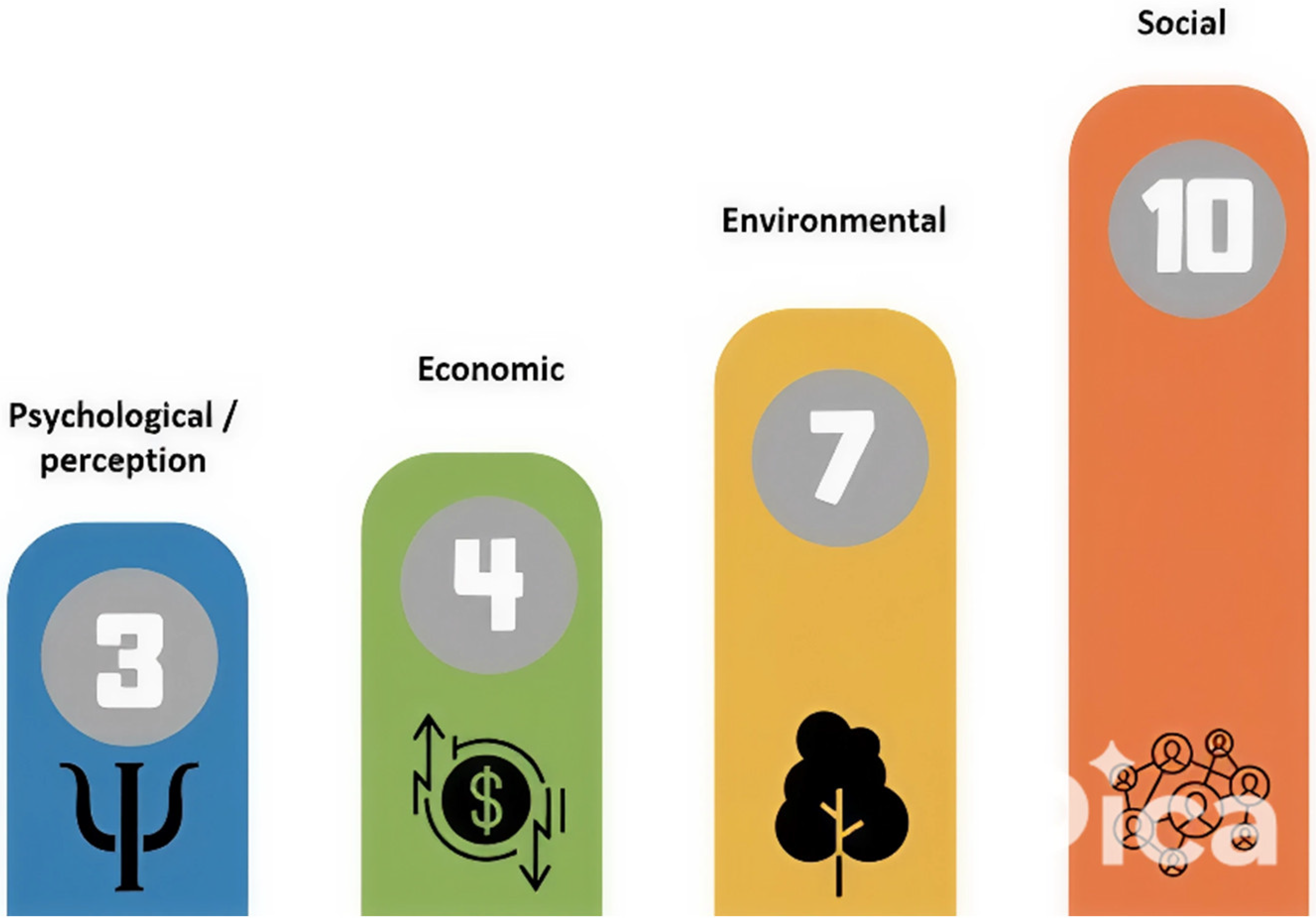

The effects vary according to the type of architectural intervention applied, which are classified into four types of impacts: social, environmental, economic, and psychological.

In

Figure 7, the social impact is the most addressed, with a total of 10 studies, as shown in

Figure 4. These articles highlight the effects derived from urban regeneration interventions, including the improvement of the sense of belonging, neighborhood integration, and citizen participation. These impacts are identified in studies such as those by [

31,

32,

33], among six other authors who reinforce this impact.

On the other hand, the environmental impact is present in seven studies, which report effects such as soil decontamination, reduction in heat islands, and reduction in environmental footprint. Studies such as those by [

19,

21] and five other studies report these impacts as a result of the intervention.

Regarding economic impacts, four studies were identified, related to the increase in real estate supply in regenerated areas as well as the attraction of both public and private investment. Authors such as [

28,

30] highlight how residual lands can energize the real estate market.

Finally, the psychological impact is addressed in three studies, which mention benefits such as reduced feelings of insecurity, increased emotional well-being, and improved visual perception of public spaces. These effects are analyzed in studies like those of [

15,

17], emphasizing sensory and emotional effects as a result of the interventions.

3.1.5. Classification and Reuse of Abandoned Urban Voids in Different Regions of the World

An analysis of 16 articles on abandoned urban voids allows for the identification of different categories of unused or degraded urban spaces as well as approaches and regeneration strategies that vary according to the urban context and typology. Of the 16 articles reviewed, 14 were classified as highly important, clear, and relevant to the topic, while two were omitted due to their mixed or ambiguous classification, namely those by [

2,

4].

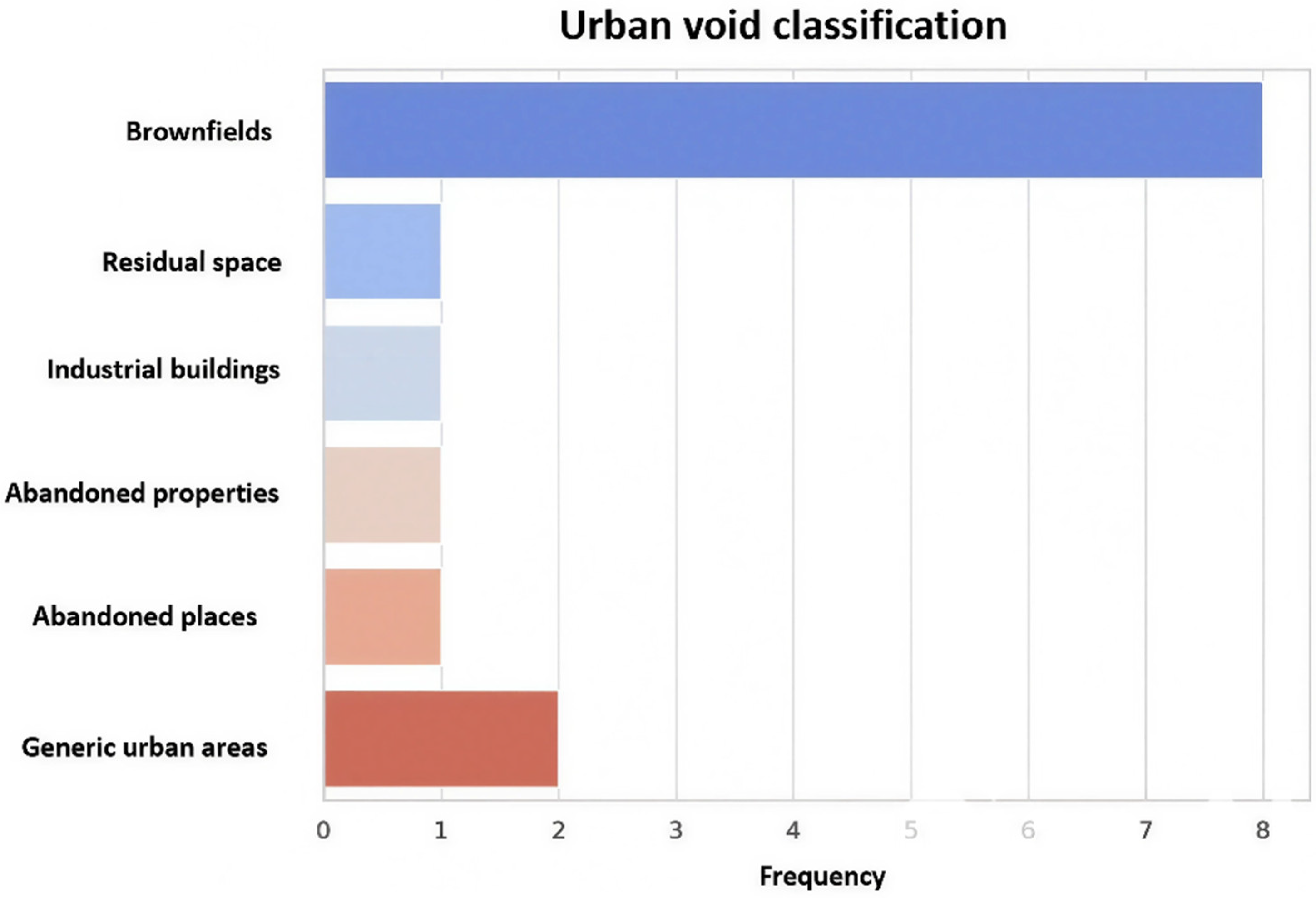

In

Figure 8, brownfields are previously urbanized lands, commonly industrial, that have been abandoned or contaminated, which seek environmental remediation, architectural regeneration, and adaptive reuse. The following authors are [

9,

18,

19,

20,

21,

27,

28,

30].

Unused urban spaces, abandoned urban voids, or vacant lots that do not classify as industrial are examined. The aim is to evaluate the perception and preferences of the population and create a system that assesses the potential for reuse of urban spaces mentioned by [

16,

17].

Residual spaces are leftover or unused urban areas within the urban structure. It proposes the temporary reuse of residual urban spaces for markets or recreational areas, and the author conducting this research is [

22].

Industrial buildings aim to transform abandoned infrastructure into spaces with new uses. It explores the case of reusing obsolete industrial factories converted into urban agricultural spaces for production and education [

14].

Abandoned properties refer to homes or buildings in a state of neglect. The strategies focus on architectural rehabilitation and urban reintegration. It examines strategies for addressing abandoned properties in the U.S., focusing on rehabilitation and urban reintegration [

23].

Abandoned places are urban areas perceived as unsafe or deteriorated, with the challenge being the transformation to improve psychological well-being. It compares the perception of the population in abandoned places versus regenerated areas, emphasizing psychological well-being [

15].

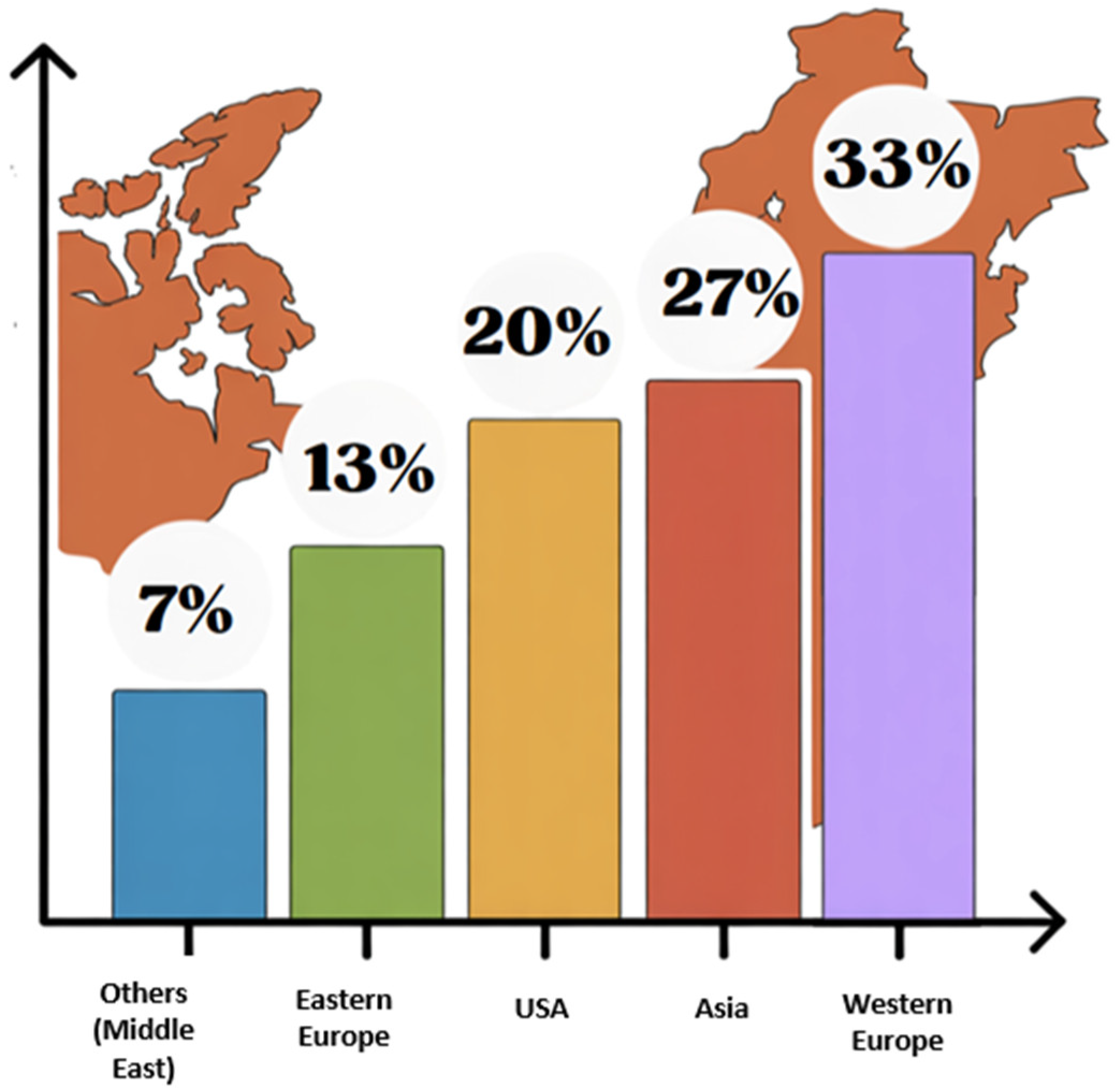

3.1.6. Geographic Distribution of Studies

Of the 16 articles studied, only 15 are related to diversity across regions of the world, reflecting a broad geographic focus. The region with the highest concentration of research is Western Europe, with six studies addressing strategies such as brownfield remediation. In Asia, there are five studies applying approaches related to green regeneration, landscape design, and temporary reuse of residual spaces.

Despite the high presence of abandoned urban voids in Latin America, no relevant studies have been identified. This absence can be attributed to low scientific production, weak institutions regarding the concept, informal-centric approaches, and limitations in sustainable urban spaces. This highlights the urgent need to promote research by proposing intervention strategies in abandoned urban voids, especially under sustainability, population inclusion, and territorial resilience frameworks.

A possible explanation for the absence of Latin American studies is not solely due to low scientific production but rather to structural factors in the generation of urban information in the region. Various studies have indicated that, in Latin American cities, the study of abandoned urban voids has mainly focused on quantifying their magnitude, location, and typology as part of land market analyses, without progressing towards methodological proposals for urban and architectural regeneration comparable to other contexts [

31,

34]. This descriptive approach limits the visibility of applied interventions and, consequently, their indexing in international academic databases such as SCOPUS.

Additionally, the heterogeneity of urban contexts and the fragmentation of territorial governance in the region hinder the production of systematic studies. According to the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, the lack of clear policies for managing vacant land and the prevalence of dispersed regulatory frameworks generate non-standardized data, preventing the development of replicable methodologies for the regeneration of abandoned urban voids [

34]. These structural conditions explain why, despite the significant presence of abandoned urban voids in Latin American cities, studies with methodologies compatible with those analyzed in this review were not identified.

In

Figure 9, China focuses on strategies for green regeneration, urban landscaping, and analysis of reconversion models. These actions respond to high population density and the need to reduce the urban ecological footprint while considering sustainability and ecological adaptation. The authors are [

19,

21,

22,

28,

29].

Abandoned urban voids in Western Europe include industrial spaces, abandoned areas, and degraded central zones, ranging from productive agricultural reuse to methods for assessing urban potential. Approaches focusing on sustainability and social function are applied, considering environmental, psychological, and community impacts. The authors are [

12,

14,

15,

16,

20,

30].

In the U.S., strategies are being sought to strengthen community living through community centers, parks, and libraries, based on adaptive reuse with social objectives aimed at public utility and reducing urban degradation [

18,

23].

In Eastern Europe, strategies focus on citizen perception and biodiversity as part of regenerative urban design. The preferences of the population and the recovery of spaces in former industrial areas are being studied [

10,

17].

In other parts of the Middle East, such as in Turkey, a strategy is proposed based on the temporary reuse of residual spaces, especially in urban areas far from the city center. Immediate social reactivation is prioritized without making significant modifications to the environment [

22].

4. Discussion

The mathematical results confirm a trend towards the sustainable intervention of abandoned urban voids through architectural strategies, with adaptive reuse and architectural regeneration standing out as the most frequent approaches. These findings are consistent with previous studies indexed in Scopus, such as those by [

10,

11,

14], which highlight the transformative potential of industrial or residual spaces into infrastructures with social, economic, and environmental value. Chowdhury and Escolà-Gascón [

9,

15] agree in noting reuse as an effective solution to urban degradation.

In the current review, six of the sixteen articles address this approach with proposals that include temporary uses, such as gardens, parks, and markets, as well as the structural conversion of industrial facilities. In contrast, the architectural regeneration identified in five studies focuses on the morphological and functional recomposition of the urban environment. Studies such as those by Sharifi and MArino [

2,

4] complement this perspective by analyzing the landscape and psychological well-being, showing that the transformation of the environment brings not only physical changes but also sensory and emotional improvements. At a global level, studies like that of Hosseini [

3] present concrete examples of how former spaces are integrated as centers.

The different trends are observed according to geographical regions based on their context: In Asia, studies focus on environmental aspects, landscape design, and reducing ecological impact, in response to the context of population density and pollution; in Western Europe, studies are oriented towards the recovery of industrial heritage and community sustainability [

3,

5]; in the United States, adaptive reuse stands out, although with a social focus aimed at constructing public centers, such as libraries or community centers [

7,

12]; in Eastern Europe, there is a primary focus on the perception of the population and urban biodiversity, fostering greater connection to participatory design [

6].

Among the main contributions highlighted in this article is the classification of impacts derived from architectural interventions into four integrated dimensions: social, environmental, economic, and psychological. Although the article mentions these impacts in a scattered manner, they are rarely presented in an articulated way within a systematic comparative framework.

The social impact is linked to the appropriation of space, neighborhood activation, and the improvement of the sense of belonging, as described by [

7,

13]. Aleha [

12] also emphasizes rehabilitation for communicative purposes, highlighting the importance of considering this component in urban design. The environmental impact aligns with the findings of Németh [

8], who underscore the reduction in the ecological footprint and improvements in air quality through green regeneration. However, in international articles, this approach is often addressed from the perspective of urban planning, which adds value to this study by connecting both approaches.

Regarding the economic impact, it establishes the relationship between regeneration and the attraction of real estate investment, similar to what is suggested by Negrello and Neprise [

14,

16]. However, this relationship still requires further analysis and evidence to assess its financial sustainability. Finally, the psychological impact constitutes one of the most novel contributions in research, such as that of Marino and Brighenti [

4,

6], which agree on the importance of the perception of safety and emotional well-being. However, the limited specific production suggests opportunities for future disciplinary research that incorporates environmental psychology approaches in the analysis of regeneration.

Another element that distinguishes this article from the rest is the inclusion of approaches with less analysis and depth, the evaluation of preferences Brighenti [

6], the selection of intervention models Negrello [

14], and environmental remediation Chowdhury [

9]. Although these strategies each have only one study, they demonstrate the level of research achieved according to the type of intervention. In the reviewed literature, particularly in regions such as Asia and Eastern Europe, there was evidence of development in theoretical and methodological models integrating into ecosystemic approaches, as seen in the cases of Sharifi and Escolà-Gascón [

2,

15]. This review recovers these contributions and systematizes them to subsequently propose them in future urban plans.

Regarding the methodology used, this article employs the Parsifal tool and the PRISMA 2020 diagram, ensuring greater rigor in the systematized information. This allowed for the acquisition of diverse and multiple approaches in different regions as well as the identification of significant thematic gaps and the classification of impacts, enabling a comparative perspective. On the other hand, an identified limitation was the lack of dependence on the language identified in the indexed databases, which may have excluded relevant experiences outside of the preferred languages.

One of the most important findings was the absence of studies conducted in Latin America in the SCOPUS database, despite the fact that this region contains the largest number of abandoned urban voids. This situation may be due to the low number of indexed studies, urban informality, or lack of planning. Studies such as those by Kim [

11] in Turkey demonstrate how countries with more recent institutional structures have been able to consolidate participatory intervention strategies.

While this systematic review provides a structured view of the architectural strategies applied to abandoned urban voids, it presents certain methodological limitations; firstly, the exclusion of gray literature, academic theses, and technical documents limits the epistemological and contextual diversity of the analysis; furthermore, the focus on articles indexed in English restricts the representativeness of experiences developed in Latin American, African, or Asian contexts that could contain alternative approaches to urban regeneration not formalized in scientific publications. This review concentrated on implemented architectural strategies, thus excluding theoretical or project studies without proven empirical application, which narrows the prospective perspective.

Among the documented advancements, a conceptual evolution stands out regarding the treatment of abandoned urban voids, which has shifted from a corrective logic of “functional infill” to more complex approaches of socio-spatial re-signification, ecosystemic integration, and territorial reconnection. In many of the systematized studies, there is an increasing sensitivity towards the multifunctionality of empty space as well as its potential to promote urban resilience, spatial equity, or citizen participation. This paradigm shift implies a transition from viewing voids as problems to seeing them as project opportunities, representing progress in the transdisciplinary understanding of the phenomenon.

As a future direction, there is a need to delve deeper into studies that integrate experimental practices, pedagogical approaches, or participatory methodologies related to abandoned urban voids, especially in vulnerable or informal contexts. Additionally, the intersection of digital tools (such as predictive modeling, spatial big data analysis, or environmental simulation) and regeneration processes could open up new possibilities for strategic intervention. It is suggested to explore with greater emphasis the interrelation between voids and governance scales, recognizing how regulatory frameworks, land policies, and economic models determine both the emergence and the potential regeneration of these spaces.

In light of this, it is proposed to conduct studies in under-researched regions like Latin America, thereby strengthening research in this context.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review allows for a critical analysis and structured synthesis of a set of studies addressing intervention in abandoned urban voids through architectural and urban strategies. This analysis reveals recurring patterns, predominant trends, differentiated impacts, and significant gaps in recent scientific literature. The results obtained enhance the understanding of abandoned urban voids as a strategic resource for improvement and transformation rather than merely a problem of abandonment, contributing a renewed conceptual framework for sustainable and inclusive architectural interventions applied in degraded spaces or residual areas.

One of the central findings of this review was the identification of two dominant strategies in the treatment of abandoned urban voids. Adaptive reuse, present in six of the sixteen articles, demonstrates a clear preference for converting disused structures, such as factories, warehouses, railway facilities, or abandoned hospitals, into new cultural facilities, productive spaces, collective housing, or innovation centers. These are characterized by being highly efficient from both energy and economic perspectives, as they minimize the consumption of new resources and promote the conservation of built heritage.

On the other hand, architectural regeneration is presented in five studies, proposing a more comprehensive intervention in the urban environment by combining morphological recomposition, functional redesign, and landscaping, with a focus on environmental sustainability and the improvement of urban quality. In addition to these two dominant strategies, this review identified complementary or emerging approaches such as the environmental remediation of contaminated soils, the incorporation of citizen preferences in design, the selection of intervention models, and the rehabilitation of deteriorated structures, each documented in at least one study.

The analysis allowed for the organization of the impacts of the interventions into four key dimensions: the social impact relates to the improvement of community integration through the strengthening of the sense of belonging and the promotion of citizen participation, which shows results suggesting that the interventions not only repair the physical fabric but also the social ties deteriorated by neglect or disinvestment; regarding the environmental impact, the decontamination of soils, mitigation of heat islands, and increase in green areas stand out as key strategies in response to the urban ecological crisis; in the economic sphere, benefits such as increased property values, attraction of investments, and revitalization of local economies are identified, although these effects require more robust evaluations; finally, the psychological impact emerges as a relevant dimension by linking the quality of urban space with emotional well-being, perception of safety, and symbolic appropriation of the environment.

The theoretical and practical contributions to these findings imply that the treatment of abandoned urban voids should not be limited to their elimination as urban anomalies but should aim to recognize and enhance their transformative capacity through a comprehensive and projective approach. Intervention strategies must be designed within a multidimensional analysis that includes socio-spatial, environmental, and cultural factors and that acknowledges the diversity of scales and temporalities involved in the urban regeneration process.

Despite these advances, this review identified structural limitations in the available literature, highlighting the geographical concentration of studies in European and Asian contexts, with a notable absence of research from Latin America, Africa, and the Global South. This limitation reduces contextual diversity and complicates the transfer of knowledge to urban realities that, despite their differences, share common challenges related to abandonment, fragmentation, and degradation of space. The scarcity of Latin American studies in indexed databases such as SCOPUS also reflects a gap in academic production that must be addressed through policies for scientific visibility and international collaboration.

Secondly, the observed studies show a lack of longitudinal evaluation regarding the impacts generated by interventions, as most articles present immediate or long-term results, making it difficult to conclude their effectiveness in terms of sustainability or long-term outcomes. This highlights the need for research that continuously and sustainably monitors impacts over time, indicating relevant impact indicators.

Thirdly, the analyzed studies have limitations concerning the explicitness of methodological constraints as well as a lack of replicable studies. This underscores the necessity to strengthen transparency in the research process and methodologies applicable to various urban contexts.

Future research should adopt mixed methodologies that combine quantitative analyses (such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS), accessibility metrics, and spatial modeling using Space Syntax) with qualitative approaches based on participatory analysis and ethnographic observation. This integration would allow for the construction of analytical frameworks that relate the physical and morphological characteristics of abandoned urban voids to their social and functional dynamics. In the Latin American context, where scientific production is limited, it is recommended to apply systematic reviews following the PRISMA 2020 protocol, incorporating regional databases (SciELO, RedALyC) and linking findings to land management policies and frameworks for adaptive urban planning.

It is also essential to advance architectural regeneration models that integrate rehabilitation and remediation strategies under principles of circular economy. The use of frameworks such as the Urban Regeneration Framework (URF) or the Brownfield Integrated Redevelopment Model (BIRM) could provide replicable protocols for transforming abandoned urban voids into sustainable assets. The incorporation of urban simulations and machine learning techniques (e.g., Urban Modelling Interface, CitySim) would allow for predictions of the impact of different strategies on connectivity, functional density, and environmental resilience. Finally, it is suggested to develop post-intervention longitudinal studies that assess social, environmental, and economic indicators in the long term, providing empirical evidence to validate and adjust the proposed regeneration models.

It is also suggested to advance research on technological and digital innovation applied in unused urban spaces as strategies. The application of sensors, 3D simulations, geographic information, or interaction platforms for decision-making could be a good alternative for planning and evaluating intervention processes. Additionally, the development of studies that analyze the effectiveness of different intervention models, such as the dimensions of the void to be intervened, the proposed actors, or the intended use of the void, could contribute various typologies that guide decision-making in real contexts.

Various studies have shown that abandoned urban voids generate direct psychological effects on communities, related to both the perception of safety and the sense of belonging. Research conducted in cities like Philadelphia and Baltimore demonstrates that the presence of vacant lots and abandoned buildings is associated with higher levels of anxiety, stress, and perceptions of urban disorder, while their rehabilitation leads to a significant decrease in depressive symptoms among the surrounding population [

32,

33]. These findings are consistent with environmental psychology theories, such as the Broken Windows Theory, which points to the relationship between the physical deterioration of the environment and the negative emotional impact on residents. In this sense, including the analysis of psychological impact allows for understanding abandoned urban voids not only as spatial elements but also as factors that affect mental health and social cohesion within communities [

35].

Architectural regeneration interventions in abandoned urban voids have shown direct benefits for the mental health of the population. A meta-analysis of studies conducted in the U.S. and Europe concluded that the rehabilitation of vacant lots through revegetation and landscape conditioning resulted in increases of up to 25% in the perception of safety and reductions of over 30% in self-reported symptoms of stress in vulnerable communities [

36]. These findings justify the consideration of the psychological dimension as a key contribution of this study, as they link the regeneration of abandoned urban voids with indicators of emotional well-being and social cohesion.

The integration of geographic information systems (GIS) is crucial for mapping and prioritizing abandoned urban voids in regeneration processes. In a study conducted in Porto, Portugal, the application of GIS combined with multicriteria analysis allowed for the evaluation of 212 abandoned urban voids considering accessibility, ecological connectivity, population density, and heritage value, generating a prioritization index that guided low-impact and high-efficiency urban architectural interventions [

37]. This type of methodology can be replicated in different contexts to link precise spatial data with design and planning decisions.

Complementarily, the incorporation of IoT environmental sensors has proven effective for monitoring the performance of transformed abandoned urban voids. Pilot projects in cities such as Berlin and Barcelona installed networks of temperature, noise, and air quality sensors to measure the effects of converting vacant lots into green spaces, demonstrating reductions of up to 2 °C in heat islands and improvements in the perception of environmental comfort [

38]. The integration of this real-time data with urban simulation models allows for the adjustment of architectural and landscaping strategies, turning the regeneration of voids into a dynamic process based on empirical evidence.

Finally, it is recommended to focus studies on informal or non-institutionalized abandoned urban voids that lack delineation in the cadastre and are not considered for use within urban planning. These spaces have significant potential for transformation and utilization, especially in cities with high population growth rates. In such cases, the application of these interventions can be crucial.

In general, this review provides a theoretical and methodological foundation, helping to view abandoned urban voids not as a problem but as opportunities for improvement in various areas such as social, economic, environmental, and psychological. In this way, urban environments will be generated with greater citizen participation as well as being ecologically friendly, resilient, and comfortable.