Cultural Heritage Sites as a Facilitator for Place Making in the Context of Smart City: The Case of Geelong

Abstract

1. Introduction

Literature Review

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

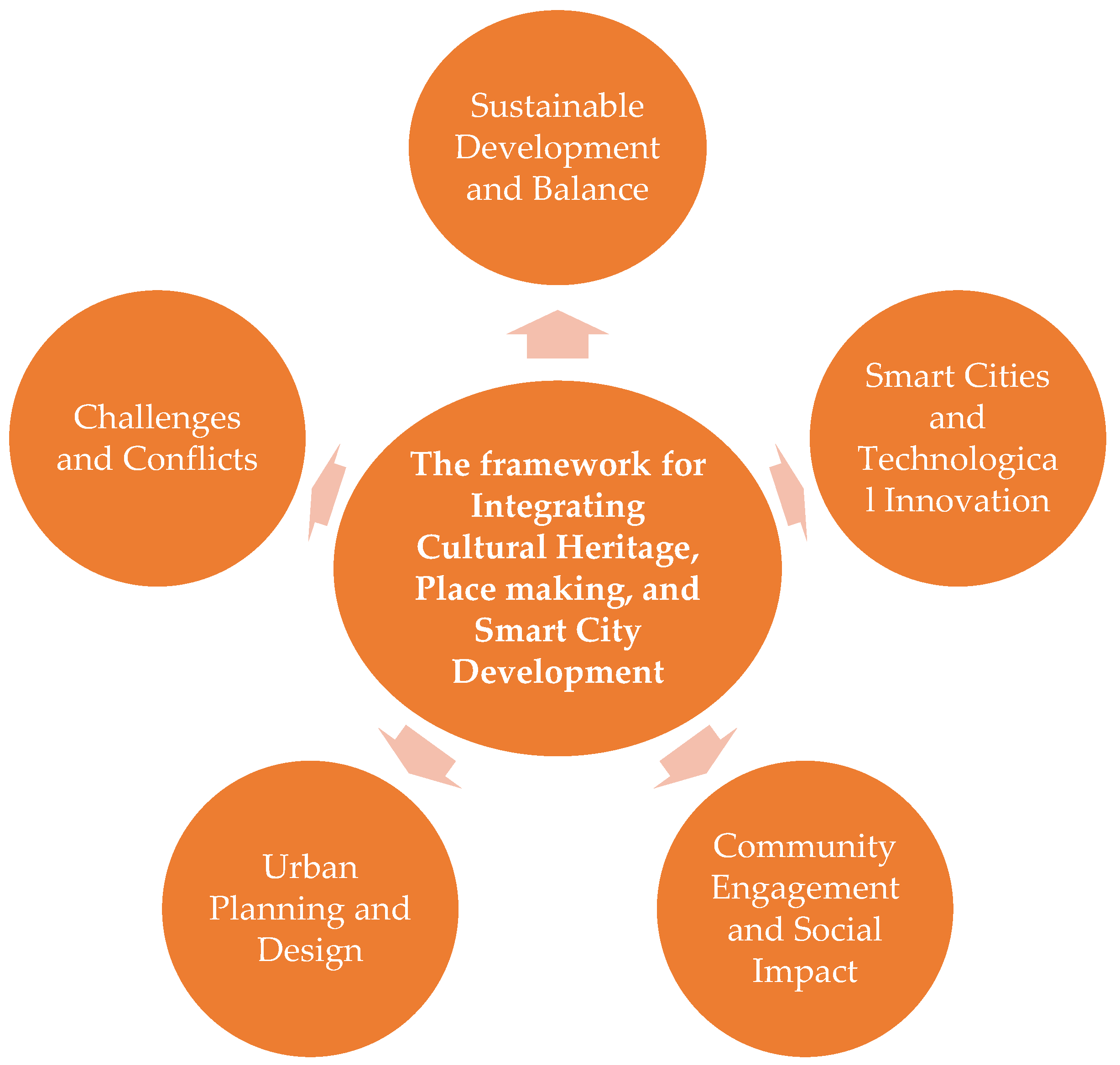

2.2. Conceptual Model

- Cultural heritage as a multidimensional urban asset (historical, symbolic, economic, and social);

- Place making as a dynamic process of spatial identity, community engagement, and cultural continuity;

- Smart city principles as an operational layer involving technology, sustainability, and participatory governance.

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Participants and Sampling Strategy

2.3.2. Interview Method and Protocol

- The role of cultural heritage in urban identity and continuity;

- Use of digital technologies for storytelling and activation of heritage;

- Community engagement and co-design;

- Sustainable planning and adaptive reuse;

- Economic and policy implications.

2.4. Data Analysis

- Familiarisation—Interview transcripts were read multiple times for immersion.

- Generating initial codes—Open coding was conducted manually to highlight recurrent ideas and categories.

- Searching for themes—Codes were grouped into potential themes and sub-themes through pattern recognition.

- Reviewing themes—Themes were reviewed in relation to coded extracts and the entire dataset for coherence.

- Defining and naming themes—Final themes were refined, clearly named, and supported by direct quotes.

- Producing the report—A narrative was developed for each theme with analytical depth and relevance to research questions.

- Heritage as Identity Anchor in Smart Cities

- Digital Technologies Enhancing Cultural Narratives

- Community Engagement and Ownership

- Adaptive Reuse and Sustainable Planning

- Economic Potential and Policy Integration

2.5. Research Tools and Validity

- Triangulation of data sources (interviews) and perspectives (from diverse disciplines);

- Member checks, where select participants reviewed thematic summaries;

- Peer debriefing, involving discussions with academic supervisors to challenge emerging interpretations.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

2.7. Summary

3. Results

3.1. Participant Overview

3.2. Thematic Analysis of Qualitative Data

3.3. Heritage as Identity Anchor in Smart Cities

- Smart City Specialist (Group 1);

- Urban Planner (Group 1 & 3);

- Cultural Anthropologist (Group 2);

- Community Developer (Group 2).

“Geelong, one of Victoria’s oldest cities, boasts significant cultural heritage from both the early European settlers and the Indigenous Wathaurong people… Over the years, each era has added new layers of significance to our heritage sites… These sites represent an ongoing dialogue between history and modernity.”(Urban Planner, City of Geelong)

“Preserving heritage might have seemed like a side issue compared to all the development happening. But now we realise these sites are absolutely crucial for the city’s soul. They give the community a shared identity, a connection to the past.”(Sustainability and Climate Expert)

“From the industrial roots of the Waterfront to the growing celebration of Wadawurrung culture, the city’s blending history with modern needs. These sites aren’t just preserved, they’re activated, creating spaces that respect the past while building community connections today.”(Smart City Specialist)

“Now, these places aren’t just reminders of the past. They’re platforms for dialogue, education, and cultural exchange… They help us bridge the gaps between different communities and understand our shared history.”(Cultural Anthropologist)

3.4. Digital Technologies Enhancing Cultural Narratives

- Urban Planner (Group 1);

- Heritage Officer (Group 2 & 3);

- Sustainability Expert (Group 1);

- Landscape Architect (Group 3).

“In Geelong, integrating cultural heritage into smart city projects means using technology not just for efficiency but to deepen connections to the city’s history and culture… For example, digital tools like augmented reality could bring the Wadawurrung heritage to life for residents and visitors.”(Smart City Specialist)

“To enhance the interpretation and storytelling of cultural heritage sites, I recommend leveraging augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) technologies… an AR app could provide additional context… displaying historical images, videos, and narratives that enrich understanding.”(Smart City Specialist)

“One really effective strategy is using geolocation-based storytelling… accessing site-specific narratives right on their smartphones… We can also collaborate with local universities and tech companies to create amazing digital exhibits and interactive displays.”(Sustainability and Climate Change Expert)

“Digital technologies have opened up so many possibilities… One great example is interactive projection mapping… QR codes… or even community-generated digital archives that make history accessible online.”(Senior Architect, Group 3)

“We can use data analytics to better understand visitor patterns at our heritage sites… This data can then inform our management strategies… We’re also exploring the use of technology to improve accessibility—such as real-time audio descriptions or virtual tours.”(Heritage Project Officer, Geelong)

3.5. Community Engagement and Ownership

- Community Developer (Group 2);

- Cultural Anthropologist (Group 2);

- Architect (Group 3);

- Landscape Architect (Group 3).

“Fostering community engagement and ownership in cultural heritage planning is all about making people feel connected, heard, and invested… participatory design… digital platforms where people can share ideas or vote on proposals.”(Smart City Specialist)

“In Geelong, we’re encouraging things like community markets, cultural events, even public gatherings within these historic spaces. This not only brings them to life but also builds a sense of community pride and ownership.”(Sustainability and Climate Expert)

“We’ve prioritised community-driven initiatives, such as local heritage committees… digital storytelling tools have enabled residents to narrate their connections to these sites, fostering a sense of ownership and pride.”(Community Developer, City of Geelong)

“Interactive digital platforms where residents can share photos, stories, and their memories of these places… It’s like creating a community archive.”(Cultural Anthropologist)

“Heritage festivals are a fantastic way to celebrate our history and get people excited about preserving it… These events can involve everyone, from local musicians and dancers to historians and volunteers.”(Heritage Project Officer, Geelong)

3.6. Adaptive Reuse and Sustainable Planning

- Architect (Group 3);

- Sustainability and Climate Expert (Group 1);

- Urban Planner (Group 1 & 3).

“Cultural heritage preservation should be seen as a foundational element of sustainable urban development… supporting sustainability by encouraging adaptive reuse of existing structures, reducing construction waste, and promoting local materials.”(Smart City Specialist)

“We’re looking at innovative approaches like adaptive reuse—taking historic buildings and giving them new life with modern, eco-friendly features. This minimises the need for new construction, which is much better for the environment.”(Sustainability and Climate Expert)

“Adaptive reuse… can be a fantastic way to breathe new life into old buildings while preserving their historical fabric.”(Heritage Consultant)

“We made sure to incorporate the character of the area by reflecting the architectural styles and reusing materials from existing structures. It ended up being this great blend where the new spaces felt like they truly belonged to the community.”(Senior Architect)

“Preserving our cultural heritage sites isn’t just about history; it’s a key part of building a sustainable city… We should recognise the environmental benefits of adapting and reusing existing buildings.”(Urban Planner)

3.7. Economic Potential and Policy Integration

- Urban Planner (Group 1 & 3);

- Smart City Specialist (Group 1);

- Heritage Consultant (Group 2);

- Project Officer (Group 3).

“The integration of cultural heritage sites into smart city development plans can have significant positive economic implications… promoting our heritage can stimulate sectors such as hospitality, retail, and services, create jobs and support local businesses.”(Smart City Specialist)

“These sites can become major attractions, draw tourists and boost local businesses… We can focus on sustainable tourism, promoting local experiences and responsible travel.”(Sustainability and Climate Expert)

“Integrating our cultural heritage sites into our smart city plans is a real economic game-changer for Geelong… These sites are huge tourist draws… Well-preserved heritage sites also increase property values and attract investment.”(Urban Planner)

“By showcasing our unique historical assets, we can attract new residents, businesses, and visitors, create jobs and contribute to a more prosperous community.”(Heritage Consultant)

“Public–private partnerships are absolutely important… imagine businesses partnering with the city to restore and adapt historic buildings into hotels or cultural hubs… It benefits both the economy and the preservation of our history.”(Urban Planner)

“By joining forces, we can come up with some really creative solutions… Our ‘Cultural Heritage Fund’ here in Geelong encourages private businesses to get involved by offering tax incentives and grants.”(Heritage Project Officer)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jacks, B.S.; Ajala, O.A.; Lottu, O.A.; Okafor, E.S. Exploring theoretical constructs of smart cities and ICT infrastructure: Comparative analysis of development strategies in Africa-US Urban areas. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 21, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Singh, R.; Srivastava, A. Analyzing the role of geospatial technology in smart city development. In Geospatial Technology and Smart Cities: ICT, Geoscience Modeling, GIS and Remote Sensing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Freestone, R.; Favaro, P. The social sustainability of smart cities: A conceptual framework. City Cult. Soc. 2022, 29, 100460. [Google Scholar]

- Ntanda, A.; Carolissen, R. Technology’s dual role in smart cities and social equality: A systematic literature. J. Local Gov. Res. Innov. 2025, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazuleviciute-Vileniske, I.; Zmejauskaite, D. ‘Archeology’ of Hidden Values of Underutilized Historic Industrial Sites in Context of Urban Regeneration and Nature-Based Solutions. Buildings 2025, 15, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursanty, E.; Rusmiatmoko, D.; Husni, M.F.D. From heritage to identity: The role of city authenticity in shaping local community identity and cultural preservation. J. Archit. Hum. Exp. 2023, 1, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.H.G.; Lee, W.H.H.; Tang, B.M.; Chen, Z. Legacy of culture heritage building revitalization: Place attachment and culture identity. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1314223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, C.M.; Treija, S.; Zaleckis, K.; Bratuškins, U.; Chen, C.H.; Chen, Y.H.; Chiang, C.T.; Jankauskaitė-Jurevičienė, L.; Kamičaitytė, J.; Koroļova, A.; et al. Digital placemaking for urban regeneration: Identification of historic heritage values in Taiwan and the Baltic states. Urban Plan. 2021, 6, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirzadeh, M.; Sharifi, A. The evolutionary path of place making: From late twentieth century to post-pandemic cities. Land Use Policy 2024, 141, 107124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Guaralda, M.; Kerr, J.; Turkay, S. Digital intervention in the city: A conceptual framework for digital placemaking. Urban Des. Int. 2024, 29, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaniotto Costa, C.; Artopoulos, G.; Djukic, A. Reframing digital practices in mediated public open spaces associated with cultural heritage. Rev. Comun. Linguagens-Cid. Futuro = J. Lang. Commun. Cities Future 2018, 48, 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Westling, C.; Hall, E.; Krell, M. Reimagining heritage buildings as technological spaces. AMPS Proc. Ser. 2020, 20, 282–288. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, S.; Chau, H.W.; Jamei, E.; Vrcelj, Z. Understanding place identity in urban scale Smart Heritage using a cross-case analysis method. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2023, 9, 729–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Yuan, H.; Li, H. Exploring the contribution of advanced systems in smart city development for the regeneration of urban industrial heritage. Buildings 2024, 14, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Whitford, M.; Arcodia, C. Development of intangible cultural heritage as a sustainable tourism resource: The intangible cultural heritage practitioners’ perspectives. In Authenticity and Authentication of Heritage; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021; pp. 34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.-K.; Lim, H.H.; Tan, S.H.; Kok, Y.S. A cultural creativity framework for the sustainability of intangible cultural heritage. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 439–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas, J.; Lerones, P.M.; Medina, R.; Zalama, E.; Gómez-García-Bermejo, J. Classification of architectural heritage images using deep learning techniques. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtorf, C.; DeSilvey, C.; Harrison, R. Heritage Futures: Comparative Approaches to Natural and Cultural Heritage Practices; UCL Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, K.-A.; Kern, M.L.; Rozek, C.S.; McInerney, D.M.; Slavich, G.M. Belonging: A review of conceptual issues, an integrative framework, and directions for future research. Aust. J. Psychol. 2021, 73, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skounti, A. Tangible and Intangible Heritage: Two UNESCO Conventions. In Evolving Heritage Conservation Practice in the 21st Century; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Buonincontri, P.; Marasco, A.; Ramkissoon, H. Visitors’ experience, place attachment and sustainable behaviour at cultural heritage sites: A conceptual framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, D.S.; Alves, F.B.; Vásquez, I.B. The relationship between intangible cultural heritage and urban resilience: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, H. Intangible cultural heritage and soft power–exploring the relationship. Int. J. Intang. Herit. 2017, 12, 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, D. About Corayo: A Thematic History of Greater Geelong; City of Greater Geelong: Geelong, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kalandides, A. The problem with spatial identity: Revisiting the “sense of place”. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2011, 4, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendlebury, J.; Porfyriou, H. Heritage, urban regeneration and place-making. J. Urban Des. 2017, 22, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincher, R.; Pardy, M.; Shaw, K. Place-making or place-masking? The everyday political economy of “making place”. Plan. Theory Pract. 2016, 17, 516–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mısırlısoy, D.; Günçe, K. Adaptive reuse strategies for heritage buildings: A holistic approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 26, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. Downtown is for People. Explod. Metrop. 1958, 168, 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ellery, P.; Ellery, J. Strengthening community sense of place through placemaking. Urban Plan 2004, 4, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuma, B.; Rooijackers, M. Uncovering the potential of urban culture for creative placemaking. J. Tour. Futures 2020, 6, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Public Places Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vukmirovic, M.; Gavrilović, S. Placemaking as an approach of sustainable urban facilities management. Facilities 2020, 38, 801–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hes, D.; Hernandez-Santin, C. Placemaking Fundamentals for the Built Environment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Colella, S. Embedding engagement: Participatory approaches to cultural heritage. Scires-It 2019, 9, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Quintero, A.M.; González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Roldán, J.L. The role of authenticity, experience quality, emotions, and satisfaction in a cultural heritage destination. In Authenticity and Authentication of Heritage; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021; pp. 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Liotine, M.; Ramaprasad, A.; Syn, T. Managing a smart city’s resilience to ebola: An ontological framework. In Proceedings of the 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Koloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaprasad, A.; Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Syn, T. A unified definition of a smart city. In Proceedings of the Electronic Government: 16th IFIP WG 8.5 International Conference, EGOV 2017, St. Petersburg, Russia, 4–7 September 2017; Proceedings 16. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Somayaji, S.R.K.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Alazab, M.; Maddikunta, P.K.R. A review on deep learning for future smart cities. Internet Technol. Lett. 2022, 5, e187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidou, M.; Karachaliou, E.; Angelidou, T.; Stylianidis, E. Cultural heritage in smart city environments. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, 42, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halegoua, G. Smart Cities; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Radziejowska, A.; Sobotka, B. Analysis of the social aspect of smart cities development for the example of smart sustainable buildings. Energies 2021, 14, 4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Dambruch, J.; Peters-Anders, J.; Sackl, A.; Strasser, A.; Fröhlich, P.; Templer, S.; Soomro, K. Developing knowledge-based citizen participation platform to support Smart City decision making: The Smarticipate case study. Information 2017, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, Y.; Kashani, M.H.; Akbari, M.; Mahdipour, E. Leveraging big data in smart cities: A systematic review. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2021, 33, e6379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Babcock, J.; Pham, T.S.; Bui, T.H.; Kang, M. Smart city as a social transition towards inclusive development through technology: A tale of four smart cities. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2023, 27 (Suppl. S1), 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caragliu, A.; Del Bo, C.F. Smart innovative cities: The impact of Smart City policies on urban innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 142, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zygiaris, S. Smart city reference model: Assisting planners to conceptualize the building of smart city innovation ecosystems. J. Knowl. Econ. 2013, 4, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammen, D.M.; Sunter, D.A. City-integrated renewable energy for urban sustainability. Science 2016, 352, 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, T.; Pardo, T.A. Conceptualizing smart city with dimensions of technology, people, and institutions. In Proceedings of the 12th Annual International Digital Government Research Conference: Digital Government Innovation in Challenging Times, College Park, MD, USA, 12–15 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- El-Basha, M. Urban interventions in historic districts as an approach to upgrade the local communities. HBRC J. 2021, 17, 329–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladini, A.; Dhanda, A.; Ortiz, M.R.; Weigert, A.; Nofal, E.; Min, A.; Gyi, M.; Su, S.; Van Balen, K.; Quintero, M.S. Impact of virtual reality experience on accessibility of cultural heritage. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, 42, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, N.M.; Coolsaet, B.; Sterling, E.J.; Loveridge, R.; Gross-Camp, N.D.; Wongbusarakum, S.; Sangha, K.K.; Scherl, L.M.; Phan, H.P.; Zafra-Calvo, N.; et al. The role of Indigenous peoples and local communities in effective and equitable conservation. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichler, J. Intangible cultural heritage, inequalities and participation: Who decides on heritage? Int. J. Hum. Rights 2021, 25, 793–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.; Skinner, H.; Dennis, C.; Melewar, T. Towards a theoretical framework on sensorial place brand identity. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2020, 13, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seamon, D. Sense of place. In International Encyclopedia of Geography: People, the Earth, Environment, and Technology; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, G. Pre-European vegetation in the Geelong region. In Geelong’s Changing Landscape: Ecology, Development and Conservation; CSIRO: Canberra, Australia, 2019; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Novacevski, M.; Zižek, S. The post-industrial landscape of Geelong. In Geelong’s Changing Landscape: Ecology, Development and Conservation; Jones, D.S., Roös, P.B., Eds.; CSIRO: Canberra, Australia, 2019; pp. 249–260. [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan, S.; McIntyre, P.; McCutcheon, M. Australian Cultural and Creative Activity: A Population and Hotspot Analysis: Geelong and Surf Coast; Digital Media Research Centre: Brisbane, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gathen, C.; Skoglund, W.; Laven, D. The UNESCO creative cities network: A case study of city branding. In International Symposium: New Metropolitan Perspectives; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 727–737. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovski, A.; Djukic, A.; Maric, J.; Kazak, J. Digital tools and digital pedagogy for placemaking. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.M.; Khoo, C.K.; Pancholi, S. Augmented Geelong: Digital technologies as a tool for place-A case of regional town of Geelong. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Architectural Science Association, Perth, Australia, 1–2 December 2022; pp. 144–155. [Google Scholar]

- Allam, Z.; Newman, P. Redefining the smart city: Culture, metabolism and governance. Smart Cities 2018, 1, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Fouseki, K. Sustaining the Fabric of Time: Urban Heritage, Time Rupture, and Sustainable Development. Land 2025, 14, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tousi, E.; Pancholi, S.; Md, M.R.; Khoo, C.K. Cultural heritage sites as a facilitator for place making in the context of smart city: The case of Geelong. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, D.; Clark, M.; Southerton, C. Digitized and datafied embodiment: A more-than-human approach. In Palgrave Handbook of Critical Posthumanism; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Predescu, A. Applications: Interactive Maps and Augmented Reality. In Level Up! Exploring Gamification’s Impact on Research and Innovation; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Group | Person | Expertise |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Budrish Kapoor | Smart City Specialist |

| Group 1 | Armando Aragon | Sustainability and Climate Chage Expert |

| Group 1 | Shwiti Ravisankar | Urban Planner, City of Geelong |

| Group 2 | Mardi Hirst | Community Developer, City of Geelong |

| Group 2 | Fiona Tribe | Cultural Anthropologist |

| Group 2 | Azin Saeedi | Heritage Consultant |

| Group 2 | Benjamin Petkov | Heritage Project Officer, City of Greater Geelong |

| Group 3 | Majid Ettefaghioun | Senior Architect, Architectus |

| Group 3 | Farzaneh Khamehchian | Landscape Architect |

| Group 3 | Margie McKay | Urban Designer, City of Greater Geelong |

| Group 3 | Shwiti Ravisankar | Architect and Urban Designer, City of Greater Geelong |

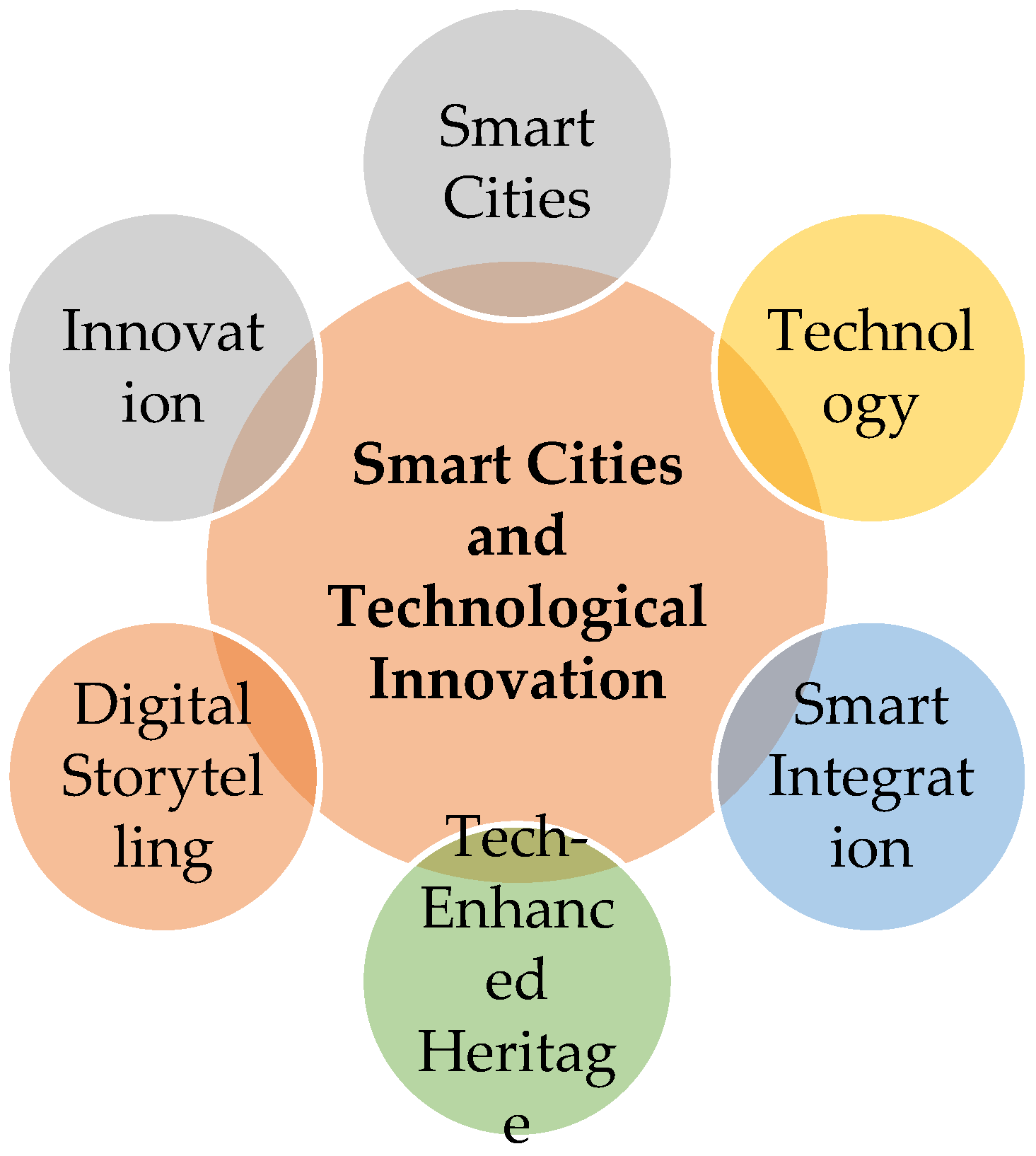

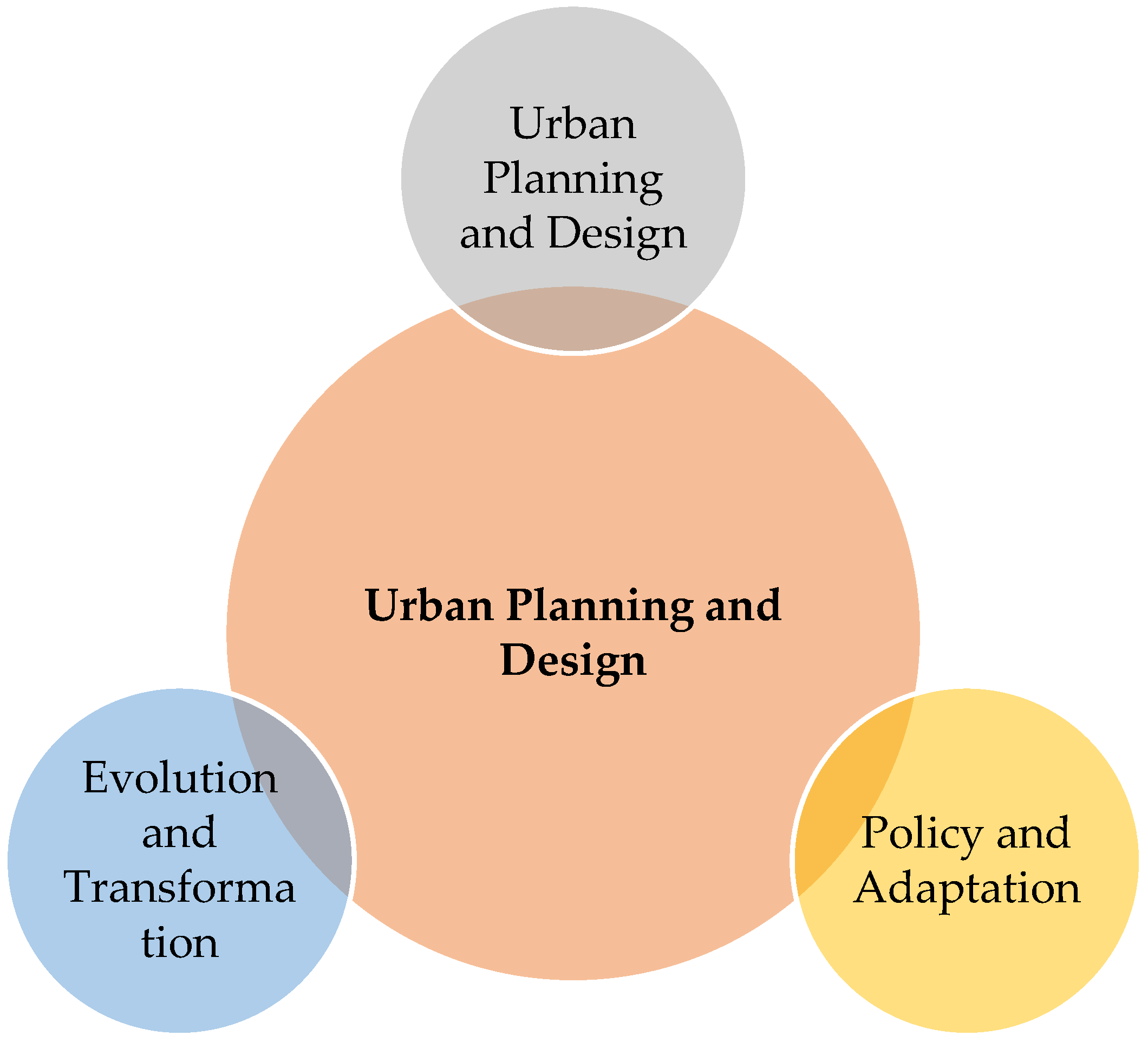

| Main Themes | Person |

|---|---|

| Sustainable Development and Balance | Sustainable Development |

| Balance | |

| Economic Growth and Value | |

| Adaptive Reuse and Integration | |

| Smart Cities and Technological Innovation | Smart Cities |

| Technology | |

| Smart Integration | |

| Innovation | |

| Tech-Enhanced Heritage | |

| Digital Storytelling | |

| Community Engagement and Social Impact | Community Engagement and Empowerment Metrics |

| Cultural Heritage and Identity | |

| Collaboration and Partnerships | |

| Urban Planning and Design | Urban Planning and Design |

| Evolution and Transformation | |

| Policy and Adaptation | |

| Challenges and Conflicts | Challenges and Conflicts |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tousi, E.; Pancholi, S.; Rashid, M.M.; Khoo, C.K. Cultural Heritage Sites as a Facilitator for Place Making in the Context of Smart City: The Case of Geelong. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9090337

Tousi E, Pancholi S, Rashid MM, Khoo CK. Cultural Heritage Sites as a Facilitator for Place Making in the Context of Smart City: The Case of Geelong. Urban Science. 2025; 9(9):337. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9090337

Chicago/Turabian StyleTousi, Elika, Surabhi Pancholi, Md Mizanur Rashid, and Chin Koi Khoo. 2025. "Cultural Heritage Sites as a Facilitator for Place Making in the Context of Smart City: The Case of Geelong" Urban Science 9, no. 9: 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9090337

APA StyleTousi, E., Pancholi, S., Rashid, M. M., & Khoo, C. K. (2025). Cultural Heritage Sites as a Facilitator for Place Making in the Context of Smart City: The Case of Geelong. Urban Science, 9(9), 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9090337