Abstract

Residential segregation remains a persistent challenge in European urban environments and is an increasing focal point in urban policy debates. This study investigates the changing geographies of ethnic diversity and residential segregation in Riga, the capital city of Latvia. The research addresses the complex dynamics of ethnic residential patterns within the distinctive context of post-socialist urban transformation, examining how historical legacies of ethnic diversity interact with contemporary migration flows to reshape neighborhood ethnic composition. Using geo-referenced data from 2000, 2011, and 2021 census rounds, we examined changes in the spatial distribution of five major ethnic groups. Our analysis employs the Dissimilarity Index to measure ethnic residential segregation and the Location Quotient to identify the residential concentration of ethnic groups across the city. The findings reveal that Riga’s ethnic landscape is undergoing a gradual yet impactful transformation. The spatial distribution of ethnic groups is shifting, with the increasing segregation of certain groups, particularly traditional ethnic minorities, coupled with a growing concentration of Europeans and non-Europeans in the inner city. The findings reveal distinctive patterns of ethnic diversification and demographic change, wherein long-term trends intersect with contemporary migration dynamics to produce unique trajectories of ethnic residential segregation, which differ from those observed in Western European contexts. However, the specific dynamics in Riga, particularly the persistence of traditional ethnic minority communities and the emergence of new ethnic groups, highlight the unique context of post-socialist urban landscapes.

1. Introduction

Contemporary global migration is substantially reshaping urban landscapes, as migrants predominantly settle in urban centers [1], leading to significant transformations in the ethnic composition of cities worldwide. This increasing diversification has spurred considerable research on its implications, particularly focusing on the complex dynamics of ethnic residential segregation and associated spatial inequalities. Understanding these patterns is crucial, as neighborhood ethnic composition can influence social interactions, access to resources, and the overall integration trajectories of diverse population groups within a city. The study of ethnic residential segregation in post-socialist cities presents unique analytical challenges and opportunities. Contrary to Marxist theory and the official position during the socialist era, social residential segregation was evident in cities under socialism. Moreover, in terms of ethnic segregation, it could be contended that it even “thrived” [2]. The legacy of Soviet-era migration policies, combined with the accession to the European Union (EU), recent immigration, urban shrinkage, and demographic shifts, creates a complex urban context where traditional ethnic minorities coexist with emergent migrant populations in ways that differ from patterns observed in other European cities.

Ethnic segregation studies examine inter-ethnic encounters across numerous domains [3], with ethnic residential segregation being one of the key research areas. Changes in the ethnic makeup of neighborhoods can drive spatial transformations [4] and affect the residential choices and socioeconomic outcomes of individuals in both native- and foreign-born populations. However, the factors shaping migrant residential patterns are multifaceted and debated. While socioeconomic status and self-perception play a role, the extent to which neighborhood ethnic composition, particularly the presence of co-ethnics, directly dictates residential decisions varies significantly across contexts [5,6]. Some studies suggest that immigrants often prefer proximity to co-ethnics, yet they may also favor living near native residents over other foreign groups [7]. Furthermore, factors like mixed-ethnicity households [8] and the complex pathways of long-term residents [9] add layers of complexity, indicating that spatial assimilation is not always a straightforward outcome.

In the context of post-socialist cities, these dynamics are further complicated by the persistence of housing patterns established during the socialist era, when residential allocation was largely state-controlled and market mechanisms were absent. The subsequent privatization processes and gradual introduction of market-based housing systems have created hybrid residential landscapes where historical settlement patterns interact with contemporary migration flows and individual housing choices in complex ways [10]. Latvia’s experience exemplifies these complexities. Its history, particularly during Soviet occupation, involved large-scale migration dynamics that significantly altered the demographic makeup and strained ethnic relations. Upon regaining independence in 1991, Latvia inherited a multi-ethnic society with the highest proportion of ethnic minorities among the Baltic States, nearing half the population at the time [11,12,13]. Although large-scale immigration associated with the Soviet era ceased decades ago, its legacy persists in the country’s ethnic composition, which remains unevenly distributed, with the majority of Latvia’s ethnic minority population residing in major cities, most notably the capital city of Riga.

This study contributes to the limited but growing body of research on ethnic residential patterns in post-socialist cities by providing a comprehensive longitudinal analysis of ethnic diversification and segregation in Riga, Latvia. Our research addresses a significant gap in the literature by examining how segregation processes in Riga compare to those observed in other post-socialist cities, particularly in the context of the Baltic states, and assessing the extent to which Riga’s patterns can be considered typical or specific within the broader post-Soviet urban context. Therefore, we aim to explore the residential geographies of ethnic diversity in Riga, utilizing geo-referenced population census data from 2000, 2011, and 2021. We seek to address the following research questions:

- How did the levels of ethnic residential segregation between major ethnic groups in Riga change between 2000 and 2021?

- How did the patterns of spatial over- and underrepresentation of major ethnic groups across Riga change between 2000 and 2021 at the chosen spatial scale?

A longitudinal analysis spanning these two decades provides insights into both longer-term shifts and more recent developments in ethnic residential patterns, including the geography of emerging groups. This study contributes to a deeper understanding of the dynamics shaping ethnic landscapes in post-socialist cities, offering findings relevant to urban planning and policy discussions concerning social cohesion and spatial inequalities in ethnically diverse urban settings.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides an essential background on Riga’s historical context and the contemporary ethnic and sociodemographic landscape. Section 3 details the data sources and methodologies employed, including the Dissimilarity Index and the Location Quotient. Section 4 presents the core findings on population changes, segregation trends, and the geographical distribution of ethnic groups. Section 5 provides a comprehensive discussion that contextualizes our findings within broader theoretical frameworks and compares Riga’s patterns to those observed in other post-socialist cities, particularly examining the role of suburbanization and demographic decline in shaping ethnic residential patterns. Finally, Section 6 presents our conclusions, summarizing key findings, reinforcing this study’s contributions, and reflecting on broader implications for understanding ethnic diversification in post-socialist urban contexts.

2. Riga’s Ethnic and Sociodemographic Landscape

Riga, the capital of Latvia and the largest city in the Baltic States, possesses a demographic structure that is profoundly shaped by its historical trajectory. Its legacy as a Hanseatic League trading center, followed by governance under various external powers, has cumulatively forged its contemporary ethnic composition. The Soviet occupation notably instigated significant demographic changes through state-enforced, large-scale migration policies. These policies significantly altered the city’s ethnic balance, creating a complex sociodemographic landscape that persisted following the restoration of Latvia’s independence. Consequently, Riga emerged as a city characterized by a substantial ethnic minority population, exhibiting relatively low levels of socioeconomic and ethnic residential segregation.

The 20% population decline experienced by Riga between 2000 and 2021 represents a critical structural backdrop that fundamentally shapes contemporary urban change. This demographic decline, driven by out-migration following EU accession, declining birth rates, and suburbanization processes, has created a context of urban shrinkage that significantly influences the patterns of ethnic intermixing and diversification. The selective nature of this population loss, with different ethnic groups experiencing varying rates of out-migration and age-specific demographic changes, has important implications for understanding the contemporary dynamics of residential segregation. In 2021, the city’s population was recorded at 615,000 inhabitants, approximately 20% lower than in 2000, constituting 32% of Latvia’s total population. Despite this decline, Riga retained a distinctly multi-ethnic character. Ethnic minorities represent 53% of the population, and 17% of the residents are foreign-born, originating from over 140 different countries [14]. Alongside established minority communities, recent migration flows, especially those emerging over the past decade, are contributing to increased diversity and raising considerations regarding the potential exacerbation of socio-spatial disparities within the urban fabric [15]. The phenomenon of suburbanization around Riga has become increasingly significant over the past two decades, particularly affecting the spatial distribution of the population. While comprehensive data on suburban ethnic composition remain limited, available evidence suggests that suburbanization has been diversified, covering both affluent groups and people who have moved to the suburbs in search of a cheaper life [16]. It can be posited that suburbanization has contributed to the relative concentration of ethnic minorities in Riga, particularly within large housing estates. This process mirrors patterns observed in other post-socialist cities but occurs within the specific context of Riga’s demographic decline, creating unique dynamics where suburban growth coexists with urban population loss.

To facilitate a focused analysis of ethnic diversity patterns in Riga, this study categorizes the population into five aggregate groups: Latvians, Russians, other traditional ethnic minorities, Europeans, and non-Europeans (see Table 1). While Russians are considered a traditional ethnic minority, the substantial size of the group warrants their classification as a distinct group. This approach permits a clearer examination of the demographic and socioeconomic dynamics within the remaining traditional minority populations, which include Belarusians, Ukrainians, Poles, Lithuanians, Estonians, Jews, Roma, Armenians, Tatars, and Moldovans. Recent migration trends have resulted in the emergence of minority groups comprising both Europeans and non-Europeans. These trends are characterized by the influx of skilled labor, international student mobility, and broader East–West migration patterns.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic indicators of major aggregate ethnic groups for Riga in 2000, 2011, and 2021 (authors’ calculation based on population census data from the Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia).

Table 1 presents a comprehensive longitudinal analysis of demographic and socioeconomic indicators across major aggregate ethnic groups in Riga, spanning three census years. The key demographic and socioeconomic variables encompass fundamental demographic characteristics including gender composition (percentage of women), age structure (mean age, percentage aged 0–14, and percentage aged 65+), educational attainment (percentage with university education among those aged 15+), occupational stratification (percentage in high-status and low-status occupations based on ISCO-08 classifications), and residential mobility patterns (percentage of mobile residents within the year prior to each census). The data reveal pronounced temporal transformations and persistent ethnic stratification patterns that reflect broader processes of demographic change, educational expansion, and migration dynamics in Riga, Latvia. Over the 21-year observation period, the city experienced significant demographic aging, with the mean age increasing from 39.7 to 43.0 years for the total population, though this trend manifested with considerable ethnic variation. Russians and other traditional minorities exhibited the most dramatic aging trajectories, with Russians’ mean age rising from 40.0 to 47.9 years and other traditional groups reaching 53.4 years by 2021, accompanied by substantial declines in child populations (Russians from 14.0% to 8.9% aged 0–14; other traditional from 10.1% to 3.6%) and corresponding increases in elderly populations (Russians from 15.5% to 26.0% aged 65+; other traditional from 17.9% to 32.7%). In contrast, Latvians demonstrated relative demographic stability with their child population remaining constant at 17.4% across the period, while non-European groups exhibited demographic volatility with fluctuating age structures.

The period witnessed remarkable educational expansion across all ethnic groups, with university education rates more than doubling for most populations, rising from 18.9% to 40.2% for the total population. However, this educational transformation occurred within a context of persistent ethnic stratification, with European immigrants achieving the highest educational attainment levels (48.7% by 2021) and occupational status (46.5% in high-status occupations), while non-European groups, despite substantial educational gains (from 19.6% to 42.6% university-educated), remained disproportionately concentrated in low-status occupations (increasing from 18.8% to 29.4%). Residential mobility patterns further illuminate differential integration trajectories, with non-European populations exhibiting extraordinary mobility increases (from 4.8% to 31.5%), suggesting ongoing processes of immigration. Other traditional minorities maintained the lowest mobility rates, indicating established residential patterns and aging, as migration is highly age-selective.

These patterns illustrate how ethnic diversification persists despite overall socioeconomic advancement, with demographic aging particularly affecting Russian and other traditional ethnic minorities, educational expansion benefiting all groups but maintaining relative hierarchies, and mobility patterns reflecting differential stages of life course across native Latvians, established ethnic communities, and recent immigrants in contemporary Riga. Understanding this intricate mosaic, shaped by historical legacies, ongoing demographic shifts, and significant inter-group differences in age, gender, socioeconomic standing, and residential stability, is fundamental. It provides an essential context for investigating the spatial dimensions of ethnic diversity and segregation explored in this study, recognizing that these population segments are not uniformly distributed but exhibit distinct geographical concentrations and patterns of intermixing across Riga’s neighborhoods. The interplay between these sociodemographic characteristics and the evolving spatial organization of ethnic groups forms the foundation for subsequent analysis.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed quantitative methodologies to analyze the residential geographies of major ethnic groups within Riga. The primary data source comprises census data for three distinct years: 2000, 2011, and 2021. The Latvian census primarily determines ethnicity through self-reported affiliation utilizing predefined categories. Supplementary information, such as country of birth, country of previous residence, citizenship, and, in earlier censuses, language spoken, may also inform classification. While the system accommodates approximately 160 distinct ethnic identifications, it currently lacks categories for individuals of mixed ethnicities. Notably, the proportion of residents reporting categories of “not selected” or “unknown” for ethnicity increased over the study period, reaching 4.4% in 2021.

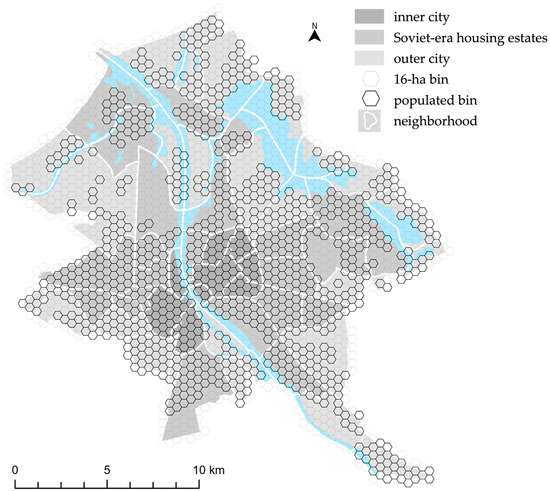

The spatial analysis was conducted using a hexagonal grid system that divided Riga into approximately one thousand hexagonal bins. This hexagonal grid approach was chosen to provide consistent spatial units that were not influenced by administrative boundary changes over time and to ensure adequate population sizes for statistical analysis while maintaining sufficient spatial resolution to capture neighborhood-level patterns. Geo-referenced population census data were aggregated into these hexagonal bins. Each populated bin thus contained counts for the analyzed ethnic groups, enabling the calculation of spatial statistics. The demographic scale of these units shifted over time; the median population within a 16 ha bin decreased from 210 persons in 2000 to 193 persons in 2021. Concurrently, the peak density also decreased, with the maximum population in the most densely populated bin falling from approximately 6700 to 4600 residents over the same period.

The study area map (see Figure 1) also delineates Riga’s broad urban structure, distinguishing between the inner-city zone, the Soviet-era housing estate zone, and the outer-city zone. These zones possess distinct historical development trajectories, built environment characteristics, demographic profiles, and migration histories. Consequently, it is hypothesized that the spatial distribution patterns of different ethnic groups vary significantly across these zones.

Figure 1.

The study area of Riga, illustrating the hexagon grid of 16 ha bins and neighborhoods by urban zones (inner-city, Soviet-era housing estates, outer-city).

To investigate the ethnic geographies of Riga, two key quantitative measures were employed. The Location Quotient (LQ) was calculated for each 16 ha bin to assess the local concentrations of specific ethnic groups. Additionally, the Index of Dissimilarity (DI) was computed to measure the overall segregation between pairs of ethnic groups across all bins within the city. Data processing, calculation of segregation indices, and spatial visualization were performed using Geo-Segregation Analyzer v.1.2 software [17] and ArcGIS Pro (version 3.0).

The Index of Dissimilarity (DI) was used to quantify the level of residential segregation between pairs of ethnic groups across the 16 ha hexagonal bins. As a standard measure in segregation research, the DI quantifies the degree of evenness in the distribution of two groups across spatial units. The index ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 signifies perfect integration (both groups are distributed identically across units) and 1 represents complete segregation (the two groups share no spatial units) [18]. The formula is:

where N is the total number of spatial units (hexagonal bins), xi is the population of ethnic group X in spatial unit i, yi is the population of ethnic group Y in spatial unit i, X is the total population of group X in the city, and Y is the total population of group Y in the city.

To visualize and quantify the relative concentration of specific ethnic groups at the local (16 ha bin) level, the Location Quotient (LQ) was calculated. The LQ compares the proportion of a specific ethnic group within a local unit to its proportion in the city as a whole. An LQ value of 1 indicates that the group’s share in the bin is identical to its city-wide share. Values greater than 1 signify overrepresentation (concentration) of the group in the bin relative to the city, whereas values less than 1 indicate underrepresentation. A range between 0.85 and 1.20 is often considered indicative of a relatively balanced distribution [19]. The formula is:

where xi is the population of ethnic group X in spatial unit i, ti is the total population of all groups in spatial unit i, X is the total population of group X in the city, and T is the total population of all groups in the city.

4. Results

This section details the empirical findings on the evolving patterns of ethnic residential distribution and segregation in Riga between 2000 and 2021. The analysis starts with an examination of relative population shifts among the defined aggregate ethnic groups, followed by an assessment of inter-group residential segregation levels using the Index of Dissimilarity (DI). Finally, the geographical distribution and local concentration patterns of each aggregate group are explored using the Location Quotient (LQ). Employing major aggregate ethnic groups facilitates the identification of broader trends related to population dynamics, residential segregation, and spatial diversity, which might be obscured when analyzing numerous individual ethnicities separately. This approach is particularly pertinent for Riga, given its historically large minority population and the relatively small, albeit growing, size of more recently arrived ethnic groups.

4.1. Population Changes by Aggregate Ethnic Group

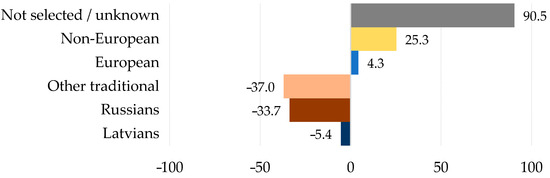

The analysis of population changes between 2000 and 2021 confirms significant shifts among major ethnic groups (see Figure 2). As anticipated, based on broader demographic trends, the populations classified as Russians and other traditional ethnic minorities experienced substantial declines, exceeding 30% for both groups. The Russian population decreased by nearly 113,000 individuals. In contrast, the decline within the Latvian group was comparatively modest in both absolute and relative terms. Conversely, the populations categorized as European and non-European exhibited growth. While modest in absolute terms, the relative increase exceeded 4% for the European group and a notable 25% for the non-European group. Consequently, the combined proportion of these two groups within Riga’s total population nearly doubled during this period, highlighting their increasing demographic presence.

Figure 2.

Relative population changes (%) by major aggregate ethnic groups between 2000 and 2021 (authors’ calculation based on data from the Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia).

A concurrent trend observed was more than a 90% increase in the number of individuals recorded with “not selected” or “unknown” ethnicity between 2000 and 2021. This considerable rise warrants acknowledgement, as the underlying factors—potentially including evolving self-identification patterns, the absence of mixed-ethnicity categories in the census, or other societal dynamics—are beyond the scope of this study’s data but represent an important contextual factor. This trend imposes a limitation, as individuals in the “not selected”/“unknown” category, representing more than 4% of Riga’s population in 2021, cannot be included in the analysis of the five defined aggregate ethnic groups.

4.2. Ethnic Residential Segregation

Inter-group residential segregation levels were assessed using the Index of Dissimilarity (DI) calculated at the 16 ha hexagonal bin scale for 2000, 2011, and 2021 (see Table 2). The values presented here indicate the degree of spatial separation between the pairs of ethnic groups. A general trend observed across the study period was an increase in DI values for most group pairings, suggesting a gradual rise in overall residential segregation within Riga. Specifically, the DI between Latvians and Russians, the city’s two largest populations, indicated moderate segregation levels that increased slightly during the study period. Other traditional ethnic minority groups consistently exhibited low segregation from Russians, indicating considerable spatial overlap, while showing similar segregation from Latvians. Conversely, both the European and non-European groups displayed substantially increasing segregation from the Russian and other traditional ethnic minority groups. Segregation between Europeans and Latvians also increased slightly, as did segregation between non-Europeans and Latvians. Notably, the segregation level between Europeans and non-Europeans remained relatively stable, with an interim increase in 2011.

Table 2.

Indices of Dissimilarity (DI) for major aggregate ethnic groups in Riga in 2000, 2011, and 2021 (authors’ calculation based on data from the Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia).

Table 2 also presents the IS values calculated between each specified group and all the other residents combined. These values measure the overall residential separation of each group from the rest of the city’s population. A consistent trend is that all five aggregate groups experienced an increase in this measure of separation between 2000 and 2021. The magnitude of this increase was most pronounced in the non-European group, followed by the European group. Examining the levels of separation by the end of the study period, other traditional minorities exhibited the lowest overall segregation. Russians displayed the next lowest level, followed by Latvians. The highest levels of overall spatial separation from the remaining population were recorded in the European and non-European groups.

4.3. Geographies of Ethnic Diversity

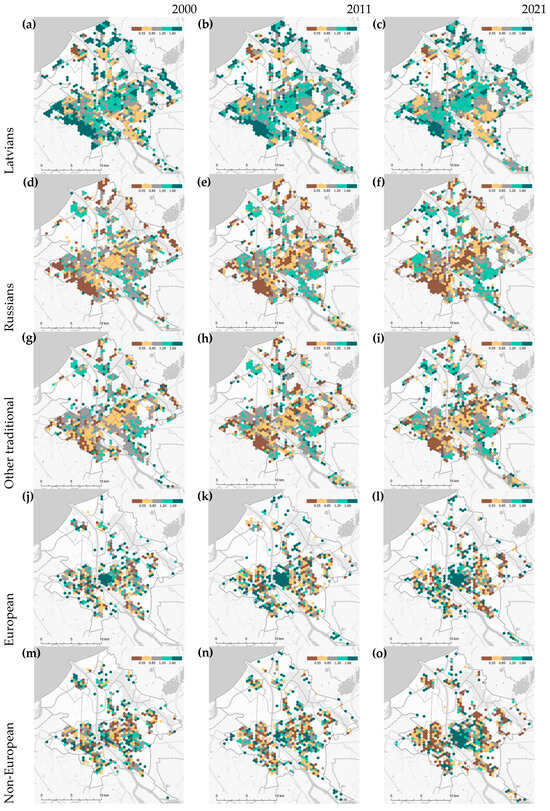

This subsection details the spatial distribution and concentration patterns of the five aggregate ethnic groups across Riga’s neighborhoods, utilizing Location Quotients (LQs) calculated at the 16 ha bin level for 2000, 2011, and 2021 (Figure 3). Throughout the study period, Latvians consistently exhibited overrepresentation in inner-city and outer-city neighborhoods, while generally showing underrepresentation in large Soviet-era housing estates, albeit with exceptions in specific greener or more prestigious locations within these estates (Figure 3a–c). Over time, their distribution appears to have become more homogeneous, with fewer areas of high over- or underrepresentation. Within the inner city, overrepresentation was notable on both banks of the Daugava River, with more optimal LQ values in the northern inner-city neighborhoods.

Figure 3.

Location Quotient (LQ) at the 16 ha hexagon bin level by major aggregate ethnic group in Riga: (a) Latvians in 2000; (b) Latvians in 2011; (c) Latvians in 2021; (d) Russians in 2000; (e) Russians in 2011; (f) Russians in 2021; (g) Other traditional minorities in 2000; (h) Other traditional minorities in 2011; (i) Other traditional minorities in 2021; (j) Europeans in 2000; (k) Europeans in 2011; (l) Europeans in 2021; (m) Non-Europeans in 2000; (n) Non-Europeans in 2011; (o) Non-Europeans in 2021 (authors’ figure based on data from the Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia).

Russians and other traditional ethnic minorities display persistent and similar spatial patterns. Both remained significantly underrepresented in outer-city areas and showed increasing underrepresentation in many inner-city neighborhoods between 2000 and 2021 (Figure 3d–i). Concurrently, their overrepresentation intensified in specific northern and southern sections of the city, predominantly within Soviet-era housing estates. While reflecting a shared tendency, these shifts towards greater spatial concentration and isolation were observed to be more pronounced for the Russian population compared to other traditional ethnic minorities.

The European group demonstrated increasing concentrations within the inner city, particularly on the right bank of the Daugava River, including marked growth in LQ values in northern inner-city areas (Figure 3j–l). In some peripheral inner-city areas, they transitioned from underrepresentation towards an optimal level or slight overrepresentation. Localized areas of overrepresentation were also observed in the southern inner city and its adjacent neighborhoods. However, underrepresentation persisted across most Soviet-era housing estates (barring some pockets of more affluent locations) and outer-city zones, where most areas remained unpopulated by Europeans, indicating a highly uneven distribution at the city scale.

The distribution of the non-European population shifted considerably. In 2000, their pattern was characterized by small, scattered clusters of varying representations across the city. By 2021, the concentration markedly increased in the right-bank inner city (Figure 3m–o) and decreased elsewhere. Inner-city neighborhoods like the Avoti neighborhood transitioned from widespread underrepresentation in 2000 to strong overrepresentation by 2021. This inner-city concentration also extended southward to the adjacent neighborhoods. Similar to Europeans, non-Europeans remained largely underrepresented in Soviet-era housing estates (except near higher education institutions) and exhibited only a minimal presence throughout most outer-city neighborhoods.

In summary, the LQ analysis revealed distinct and evolving spatial geographies for each aggregate ethnic group. Latvians displayed the most widespread distribution, becoming slightly more evenly distributed over time. Russians and other traditional minorities showed an increasing concentration within Soviet-era housing estates and a growing absence from inner- and outer-city zones. Europeans and non-Europeans both exhibited intensifying concentration within specific inner-city areas, contrasting with continued underrepresentation or even uninhibitedness across large parts of the remaining city, particularly extensive Soviet-era estates and outer-city zones.

5. Discussion

This section situates our findings within the broader theoretical framework of urban ethnic geography, offering a comparative analysis of Riga with other post-socialist cities. It specifically investigates how demographic change, suburbanization, and the post-socialist urban transition influence ethnic residential patterns.

5.1. Theoretical Framework and Causal Mechanisms

Our findings can be interpreted through various theoretical viewpoints that explain patterns of ethnic residential segregation. The spatial assimilation theory, originally developed by Massey and Denton [20], suggests that as immigrant groups achieve socioeconomic mobility, they tend to move away from ethnic enclaves toward more integrated and ethnically mixed urban neighborhoods. However, our results reveal a more complex pattern in Riga that challenges this linear progression model. The persistence and intensification of Russian and other traditional minority concentrations in Soviet-era housing estates, despite educational and occupational advancement among these groups (as shown in Table 1), suggests that spatial assimilation processes operate differently in contexts where Soviet-era settlement patterns create path-dependent residential trajectories. The place stratification model [21] provides additional explanatory power for understanding Riga’s ethnic diversification. This model emphasizes how structural barriers limit residential choices for minority groups, creating hierarchical residential systems. In Riga, ethnic infrastructure plays a crucial role, particularly in the realm of education, where Russian-speaking families have been allowed the option to enroll their children in schools where Russian is the primary language of instruction [22]. This educational policy, in conjunction with the Soviet-era housing allocation system that prioritized immigrants, significantly contributes to the ongoing overrepresentation and residential concentration of Russians and other traditional ethnic minorities in housing estates [23,24]. The differential suburbanization rates observed across ethnic groups in other Baltic state capitals [25,26] might also reflect stratified housing opportunities in the case of Riga, where Latvians demonstrate greater access to suburban housing markets, while ethnic minorities remain concentrated in housing estates. The suburbanization effect helps explain several key findings of our study. First, the increasing concentration of Latvians in outer-city residential areas reflects both new suburban development and the relative advantage of Latvians in accessing suburban housing markets. Second, the intensification of traditional minority concentrations in Soviet-era housing estates occurs partly because these groups have lower rates of suburban migration, creating a residual concentration effect. Third, the concentration of non-European migrants in inner-city areas may reflect housing market constraints, access to urban amenities, and the availability of affordable housing [27,28] in areas experiencing population decline. These suburbanization dynamics create unique challenges for ethnic integration in post-socialist cities. Unlike Western European contexts where suburban areas are increasingly becoming sites of ethnic diversity [29,30], the selective nature of suburbanization in Riga may contribute to increasing spatial separation between ethnic groups, with implications for social cohesion and integration processes.

The causal mechanisms driving the observed ethnic residential patterns operate through three primary pathways. First, the effects of demographic change create differential aging and residential mobility patterns across ethnic groups. The dramatic aging of Russians and other traditional minorities reduces their residential mobility and creates aging-in-place dynamics that intensify spatial concentration. Simultaneously, the younger age structure of new migrant populations (Europeans and non-Europeans) creates higher mobility rates and different residential preferences, contributing to their concentration in inner-city areas with better access to employment and services. Second, economic stratification mechanisms shape residential choices through differential access to housing markets. The occupational structure reveals persistent ethnic stratification, with Europeans and non-Europeans showing higher rates of high-status occupations (46.5% and 27.4% respectively) compared to traditional ethnic minorities (26.3% for Russians, 27.4% for other traditional groups). This economic stratification translates into differential housing market access, where higher-income groups can access suburban housing, while lower-income ethnic minorities remain in affordable housing estates. Third, social networks and institutional mechanisms influence residential patterns through ethnic infrastructure and community ties. The persistence of Russian-language schools, cultural institutions, and social networks in Soviet-era housing estates creates institutional anchors that maintain ethnic residential concentration even as individual preferences might favor greater integration. Conversely, new migrant groups lack established ethnic infrastructure, leading to their concentration in areas with diverse amenities and international connectivity, primarily in inner-city neighborhoods. Thus, the residential dynamics identified in Riga highlight the complex interactions between historical legacies, demographic change, and contemporary patterns of international and internal migration.

5.2. Theoretical Contribution and Comparative Analysis

Our findings contribute to the theoretical understanding of ethnic residential patterns in post-socialist cities by highlighting three distinct features of Riga’s contemporary ethnic geography. First, the concentration of new non-European migrants is highly focused within the inner-city, representing Riga’s specific urban structure, housing market dynamics, and the particular characteristics of the most recent immigration. The substantial increase in segregation levels for non-European populations suggests that Riga may be experiencing more pronounced ethnic clustering of new migrants than its Baltic counterparts. Second, the intensification of traditional minorities’ concentration in large housing estates, driven by selective out-migration, appears particularly pronounced in Riga. Third, and most crucially, the recent rise in segregation is not uniform; the sharpest increase in spatial separation occurred between new migrant groups and the established traditional minorities, whereas segregation between new migrants and the majority Latvian population increased only slightly. The persistence of Soviet-era spatial patterns, combined with new migration dynamics and selective suburbanization, creates hybrid urban landscapes that challenge conventional models of ethnic residential change developed primarily in Western contexts.

The Riga case contributes to post-socialist urban theory by demonstrating how path dependency operates in residential systems. Unlike Western cities, where ethnic residential patterns primarily reflect market-driven processes and contemporary migration flows, post-socialist cities like Riga exhibit strong path dependency, where the historical Soviet-era housing allocation system continues to influence contemporary residential choices even after fundamental political and economic transitions. This path dependency operates through multiple mechanisms: the physical infrastructure of Soviet-era housing estates that continues to house large populations; the institutional infrastructure of ethnic communities (schools, cultural centers, social networks) that developed around these residential concentrations; and the economic constraints that limit residential mobility for populations who experienced disadvantages during the post-socialist transition.

Our findings also contribute to understanding how urban shrinkage affects ethnic residential patterns. Unlike growing cities, where ethnic segregation often results from competition for desirable residential areas, shrinking cities, like Riga, experience segregation through selective out-migration and residual concentration effects. The 20% population decline between 2000 and 2021 has not affected all ethnic groups equally, creating new forms of segregation through differential mobility rather than competitive displacement. This represents a distinct pathway to ethnic residential segregation that may be characteristic of post-socialist cities experiencing demographic decline.

Comparison with other Baltic capitals reveals both common patterns and unique features of Riga’s ethnic residential dynamics. Like Tallinn, Riga exhibits a persistent concentration of Russian-speaking minorities in Soviet-era housing estates, but Riga shows more pronounced intensification of this concentration over time. All the Baltic capital cities must manage the integration of new migrant populations alongside established ethnic communities. However, Riga’s pattern of new migrant concentration in inner-city areas appears very pronounced, possibly reflecting differences in urban structure, housing markets, and economic opportunities.

5.3. Policy Implications and Further Research

The findings of this study have significant implications for urban planning and social policy in Riga and similar post-socialist cities. The persistence and intensification of ethnic residential segregation, particularly the concentration of traditional minorities in Soviet-era housing estates and new migrants in inner-city areas, requires targeted policy interventions that address both the symptoms and underlying causes of residential segregation.

Areas with high concentrations of traditional ethnic minorities, particularly Soviet-era housing estates, require comprehensive revitalization programs that address both physical infrastructure and social cohesion challenges. These programs should include improvements that enhance the quality of life in these neighborhoods without displacing existing residents and community development programs that strengthen social networks and civic participation. In addition, the concentration of new migrants in inner-city areas presents both opportunities and challenges for integration. Policy interventions should include supportive services, e.g., language training programs and community integration programs that facilitate interaction between new migrants and established residents, including both Latvians and traditional minorities.

The selective nature of suburbanization and its role in intensifying urban ethnic concentration suggest the need for more inclusive suburban development policies. Current suburban development primarily serves higher-income populations, contributing to ethnic residential segregation. The results of this study highlight the need for metropolitan-scale planning that considers the residential and mobility patterns of all ethnic groups. Current planning approaches that focus primarily on the administrative boundaries of Riga may miss important dynamics that occur in suburban municipalities. Policy interventions should include affordable housing; better coordination of public transportation to ensure that all ethnic communities have access to employment and services throughout the metropolitan area and to reduce the economic barriers to suburban residence for lower-income populations; and regional approaches to social integration that recognize the interconnected nature of urban and suburban ethnic residential patterns.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged, each of which opens important avenues for future research. First, while aggregating diverse ethnic groups into broad categories was necessary for this analysis, it may mask significant internal variations; future studies could therefore focus on specific ethnic communities to capture this heterogeneity. Second, our study concentrates on residential patterns rather than the underlying social and economic processes that drive them. A deeper understanding would require an investigation into the mechanisms behind residential choices, such as housing market dynamics, discrimination, and community formation processes. Furthermore, the analysis is confined to the administrative boundaries of Riga and does not capture suburban development in surrounding municipalities, pointing to the need for a metropolitan-scale approach to fully understand the interplay between suburbanization and ethnic residential patterns. Finally, the increasing proportion of residents not declaring an ethnic affiliation presents both a methodological challenge and a substantive phenomenon, making an inquiry into the factors driving this trend a crucial task for future research on diversity in post-socialist cities.

6. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive longitudinal analysis of ethnic diversification and residential segregation in Riga, contributing to our understanding of ethnic residential dynamics in post-socialist cities. Our findings reveal that Riga’s ethnic landscape is undergoing transformation, characterized by the persistence of historical ethnic residential patterns alongside recent immigration-driven changes.

First, our analysis demonstrates that segregation levels between traditional ethnic groups (Latvians and Russians) have remained relatively stable, with a slight increase over the study period, suggesting that the fundamental spatial relationship between these two main ethnic groups has not dramatically altered despite substantial demographic changes. This stability contrasts with more dynamic patterns observed for newer immigrant populations.

Second, this study reveals increasing segregation levels for non-European populations, with Dissimilarity Index values rising substantially between 2000 and 2021. This trend, combined with the concentration of non-European migrants in inner-city neighborhoods, suggests the emergence of new ethnic geographies that differ from historical patterns.

Third, our comparative analysis places Riga’s patterns within the broader context of post-socialist urban transition, revealing both typical characteristics shared with other Baltic cities and specific features that reflect Riga’s unique demographic and socioeconomic trajectory. These findings have important implications for understanding ethnic diversification processes in post-socialist cities more broadly. The persistence of Soviet-era spatial patterns, combined with selective suburbanization, new migration dynamics, and demographic change, creates a complex urban landscape and unique contexts for ethnic residential segregation that differ from Western European experiences. The concentration of new migrants in inner-city areas, rather than suburban dispersal, suggests alternative pathways of spatial integration that may be characteristic of shrinking post-socialist cities.

This study also highlights the importance of considering demographic decline and suburbanization as key factors shaping ethnic residential patterns in post-socialist contexts. The selective nature of population loss and suburban in-migration creates residual concentration effects that intensify ethnic clustering in certain areas while promoting dispersal in others. Future research should expand the comparative analysis to include other post-socialist cities within and beyond the Baltic region, examining how different economic trajectories, migration patterns, and policy contexts shape ethnic residential outcomes.

From a policy perspective, our findings suggest the need for differentiated approaches to ethnic integration that recognize the distinct challenges and opportunities presented by different types of ethnic concentration. Traditional minority areas require investment and support to prevent marginalization, while areas of new migrant concentration need services and infrastructure to support successful integration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.; methodology, M.B. and S.B.; software, M.B. and S.B.; validation, S.B.; formal analysis, M.B. and S.B.; investigation, S.B.; resources, M.B.; data curation, M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B. and S.B.; writing—review and editing, M.B. and S.B.; visualization, S.B.; supervision, M.B.; project administration, S.B.; funding acquisition, S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Recovery and Resilience Facility project “Internal and External Consolidation of the University of Latvia”, grant number 5.2.1.1.i.0/2/24/I/CFLA/007.

Data Availability Statement

The georeferenced census data utilized in this study are governed by an agreement between the Central Statistical Bureau of the Republic of Latvia and the University of Latvia. Disaggregated ethnic data are deemed sensitive, and their dissemination may potentially compromise individual privacy. The data in question were anonymized and processed in compliance with a confidentiality agreement, adhering to all data protection, privacy regulations, and contractual obligations. For further information regarding data usage, please contact maris.berzins@lu.lv.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Gemini Advanced 2.5 Pro (Google) for the purposes of text editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Benassi, F.; Bonifazi, C.; Heins, F.; Lipizzi, F.; Strozza, S. Comparing Residential Segregation of Migrant Populations in Selected European Urban and Metropolitan Areas. Spat. Demogr. 2020, 8, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcińczak, S.; Gentile, M.; Stȩpniak, M. Paradoxes of (Post)Socialist Segregation: Metropolitan Sociospatial Divisions under Socialism and after in Poland. Urban Geogr. 2013, 34, 327–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ham, M.; Tammaru, T. New Perspectives on Ethnic Segregation over Time and Space. A Domains Approach. Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammaru, T.; Marcin’czak, S.; Aunap, R.; van Ham, M.; Janssen, H. Relationship between Income Inequality and Residential Segregation of Socioeconomic Groups. Reg. Stud. 2020, 54, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichter, D.T.; Parisi, D.; Ambinakudige, S. The Spatial Integration of Immigrants in Europe: A Cross-National Study. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2020, 39, 465–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järv, O.; Masso, A.; Silm, S.; Ahas, R. The Link Between Ethnic Segregation and Socio-Economic Status: An Activity Space Approach. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2021, 112, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibraimovic, T.; Hess, S. A Latent Class Model of Residential Choice Behaviour and Ethnic Segregation Preferences. Hous. Stud. 2018, 33, 544–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindale, A.; Klocker, N. Neighborhood Ethnic Diversity and Residential Choice: How Do Mixed-Ethnicity Couples Decide Where to Live? Urban Geogr. 2021, 42, 744–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolt, G.; van Kempen, R. Ethnic Segregation and Residential Mobility: Relocations of Minority Ethnic Groups in the Netherlands. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2010, 36, 333–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boterman, W.R.; Musterd, S.; Manting, D. Multiple Dimensions of Residential Segregation. The Case of the Metropolitan Area of Amsterdam. Urban Geogr. 2021, 42, 481–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutland, P. Thirty Years of Nation-Building in the Post-Soviet States. Natl. Pap. 2023, 51, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garda-Rozenberga, I.; Zirnite, M. Ethnic Diversity in the Construction of Life Stories in Latvia. Acta Balt. 2017, 41, 266–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, Á. Ethnic Diversity and Its Spatial Change in Latvia, 1897–2011. Post. Sov. Aff. 2013, 29, 404–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia. Population and Its Characteristics. Available online: https://data.stat.gov.lv/pxweb/en/OSP_PUB/START__POP__IR/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Krišjāne, Z.; Bērziņš, M. Intra-Urban Residential Differentiation in the Post-Soviet City: The Case of Riga, Latvia. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2014, 63, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krisjane, Z.; Berzins, M. Post-Socialist Urban Trends: New Patterns and Motivations for Migration in the Suburban Areas of Rīga, Latvia. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apparicio, P.; Martori, J.C.; Pearson, A.L.; Fournier, É.; Apparicio, D. An Open-Source Software for Calculating Indices of Urban Residential Segregation. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2014, 32, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D.S.; Denton, N.A. The Dimensions of Residential Segregation. Soc. Forces 1988, 67, 281–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.A.; Chung, S.Y. Spatial Segregation, Segregation Indices and the Geographical Perspective. Popul. Space Place 2006, 12, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D.S.; Denton, N.A. Spatial Assimilation as a Socioeconomic Outcome. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1985, 50, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J.R.; Alba, R.D. Locational Returns to Human Capital: Minority Access to Suburban Community Resources. Demography 1993, 30, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutland, P. Introduction: Nation-Building in the Baltic States: Thirty Years of Independence. J. Balt. Stud. 2021, 52, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.B.; Tammaru, T. Modernist Housing Estates in the Baltic Countries: Formation, Current Challenges and Future Prospects. In Housing Estates in the Baltic Countries; Urban Book Series; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gentile, M.; Sjöberg, Ö. Housing Allocation under Socialism: The Soviet Case Revisited. Post. Sov. Aff. 2013, 29, 173–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammaru, T.; van Ham, M.; Leetmaa, K.; Kährik, A.; Kamenik, K. The Ethnic Dimensions of Suburbanisation in Estonia. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2013, 39, 845–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubarevičienė, R.; Burneika, D.; van Ham, M. Ethno-Political Effects of Suburbanization in the Vilnius Urban Region: An Analysis of Voting Behavior. J. Balt. Stud. 2015, 46, 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hans, N.; Hanhörster, H.; Polívka, J.; Beißwenger, S. The Role of Arrival Spaces in Integrating Immigrants. A Critical Literature Review. Raumforsch. Raumordn. 2019, 77, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolt, G.; Phillips, D.; Van Ronald, K. Housing Policy, (De)Segregation and Social Mixing: An International Perspective. Hous. Stud. 2010, 25, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.; Dwyer, C.; Ahmed, N. Ethnic and Religious Diversity in the Politics of Suburban London. Political Q. 2019, 90, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catney, G.; Wright, R.; Ellis, M. The Evolution and Stability of Multi-Ethnic Residential Neighbourhoods in England. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2021, 46, 330–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).