Exploring the 15-Minutes City Concept: Global Challenges and Opportunities in Diverse Urban Contexts

Abstract

1. Introduction

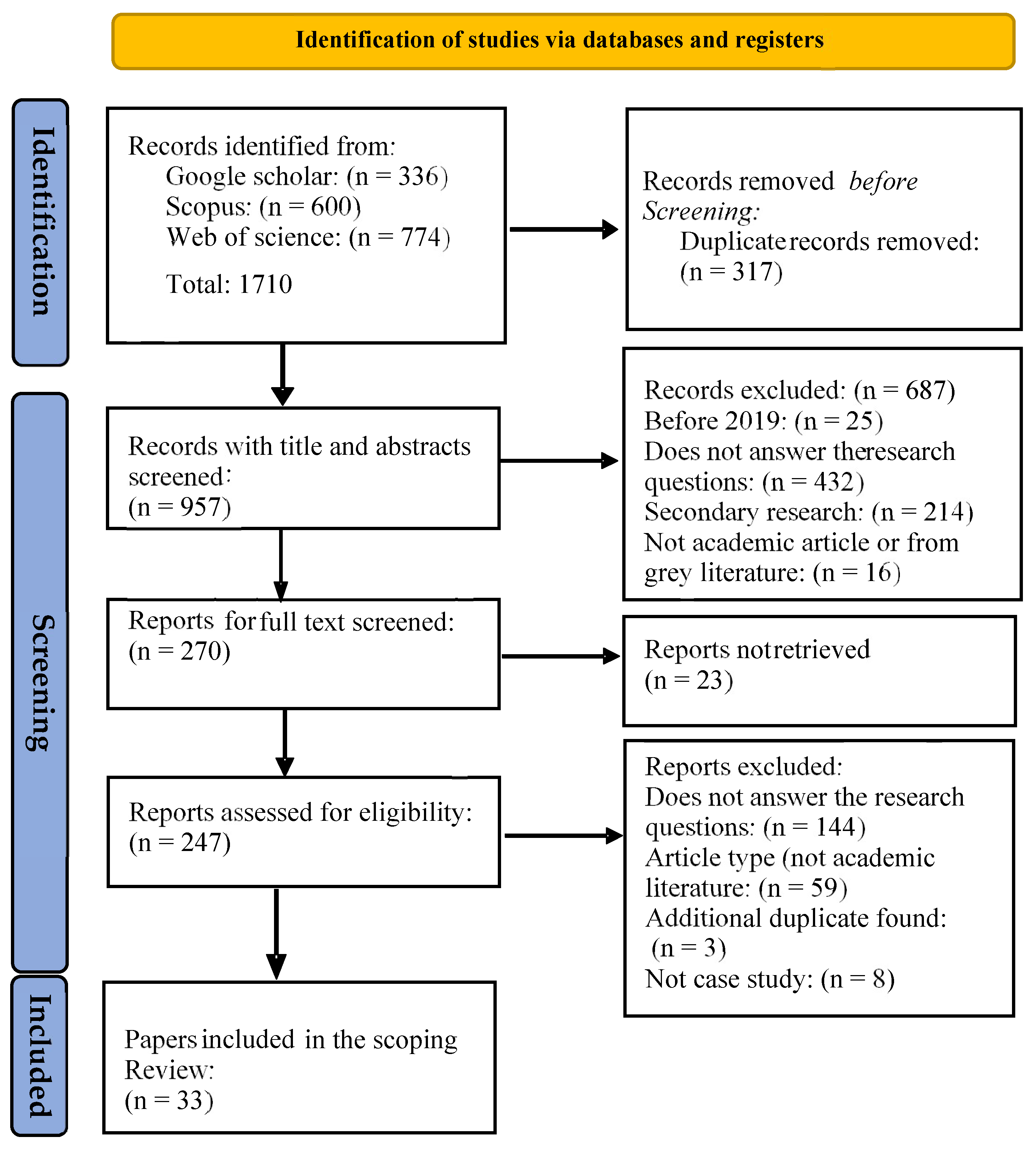

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

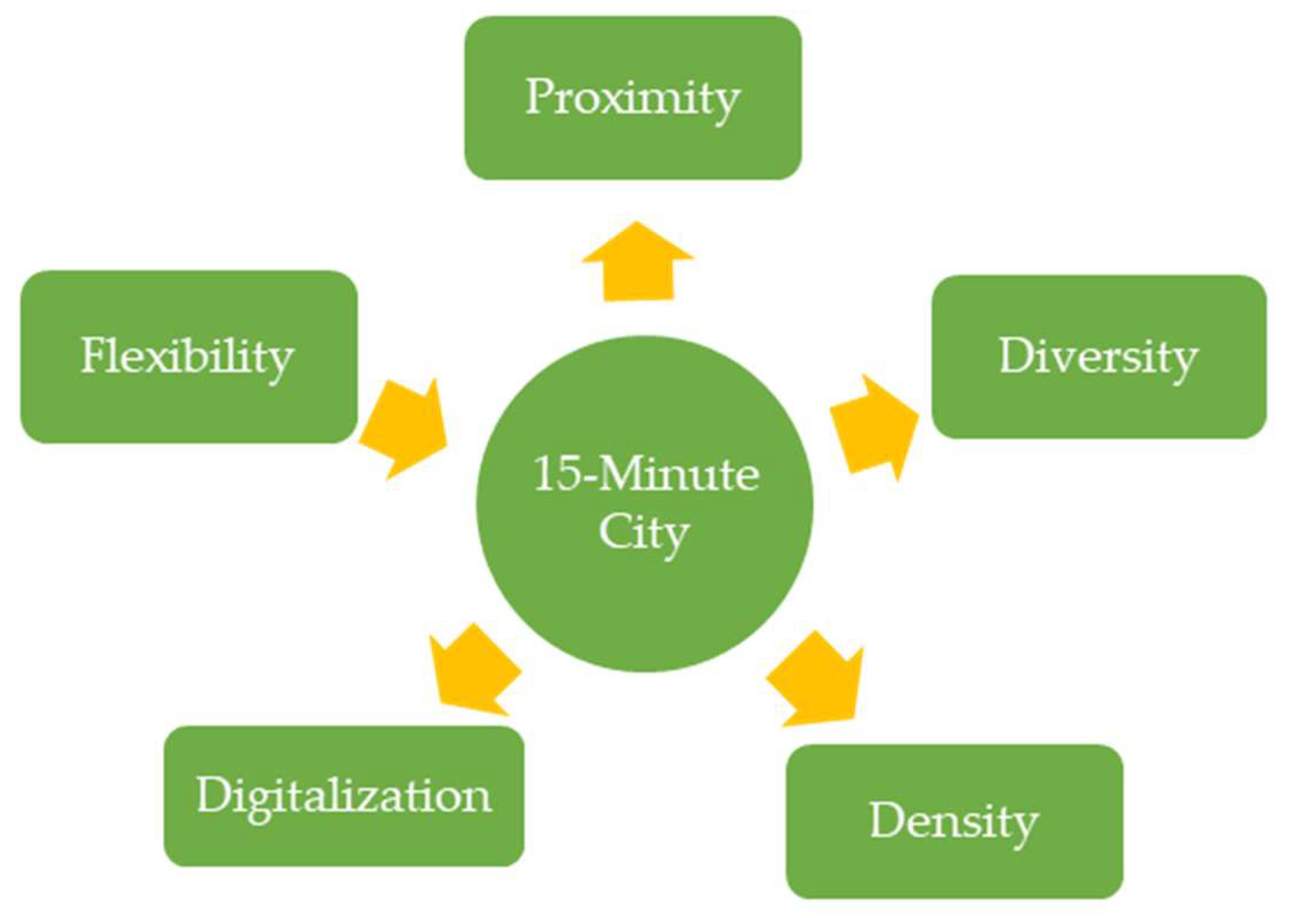

3.1. Key Components of 15-Minute Cities and Global Urban Performance

3.2. Urban Planning Tools and Strategies

3.3. Comparative Analysis of 15 MC Implementation Across Global Regions

3.3.1. Europe (Paris, Barcelona, Oslo, Lisbon, Rome, Milan, etc.)

3.3.2. North America and Oceania (Portland, Montréal, Auckland, Hamilton)

3.3.3. Asia-Pacific Region (Beijing, Shanghai, Chengdu, Jakarta, Surabaya, Melbourne, Auckland etc.)

3.4. Challenges in Dense and Resource-Constrained Settings

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 15-minutes city | 15 MC |

Appendix A

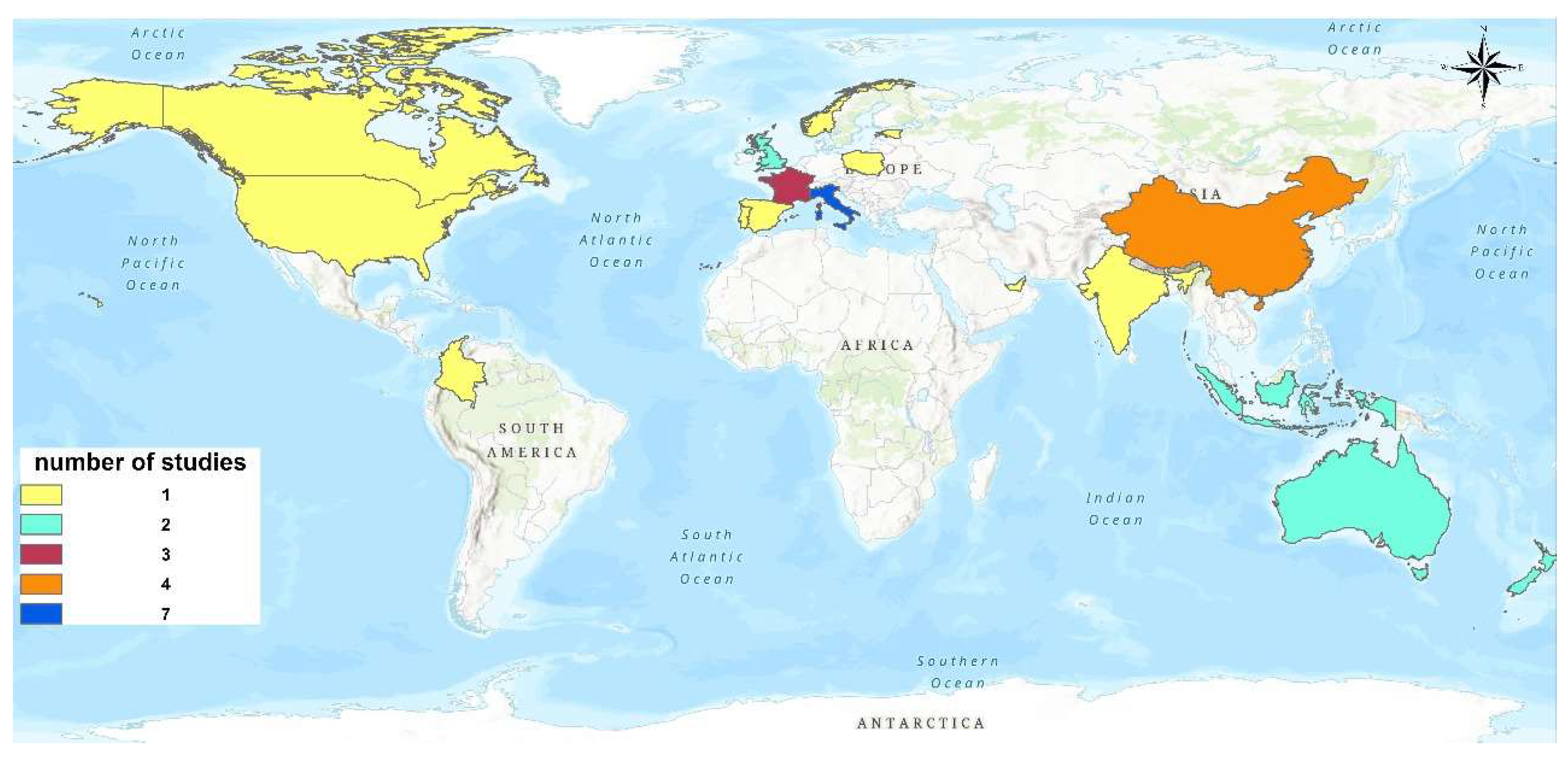

| Country | Cities Analyzed | # of Studies | Developed/Developing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | Rome, Milan, Naples, Turin, Cagliari, Pisa, Palermo, Perugia, Trieste | 7 | Developed |

| China | Beijing, Shanghai, Chengdu, Guangzhou | 5 | Developing |

| USA | Portland, Kapolei | 3 | Developed |

| France | Paris | 3 | Developed |

| Australia | Melbourne | 2 | Developed |

| Spain | Barcelona | 2 | Developed |

| India | Mumbai, New Delhi, Bhubaneswar | 2 | Developing |

| Indonesia | Surabaya, Surakarta, Jakarta | 2 | Developing |

| UK | London | 2 | Developed |

| Portugal | Lisbon | 2 | Developed |

| Norway | Oslo | 1 | Developed |

| Germany | Munich | 1 | Developed |

| Poland | Krakow | 1 | Developed |

| Greece | Thessaloniki | 1 | Developed |

| New Zealand | Hamilton, Auckland | 2 | Developed |

| Estonia | Tallinn | 1 | Developed |

| Canada | Montréal | 2 | Developed |

| Colombia | Bogotá | 1 | Developing |

| UAE | Dubai | 1 | Developing |

| Nigeria | Lagos | 1 | Developing |

| S. No | Ref. | Year | Proximity | Accessibility and Walkability | Density | Diversity | Mixed Use | Adaptability | Flexibility | Human-Scale Urban Design | Connectivity | Digitalization | Inclusive Urban Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [1] | 2024 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 2 | [3] | 2024 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| 3 | [5] | 2023 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| 4 | [9] | 2022 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| 5 | [14] | 2022 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| 6 | [17] | 2022 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 7 | [18] | 2021 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 8 | [20] | 2024 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| 9 | [24] | 2019 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| 10 | [25] | 2021 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 11 | [26] | 2021 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| 12 | [31] | 2022 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 13 | [32] | 2022 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 14 | [34] | 2024 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 15 | [35] | 2023 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 16 | [36] | 2023 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 17 | [37] | 2022 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 18 | [38] | 2023 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 19 | [39] | 2024 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| 20 | [40] | 2021 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| 21 | [41] | 2022 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 22 | [43] | 2024 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 23 | [45] | 2022 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 24 | [46] | 2023 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| 25 | [47] | 2023 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| 26 | [48] | 2023 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| 27 | [49] | 2023 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 28 | [33] | 2023 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| 29 | [51] | 2022 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| 30 | [52] | 2020 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 31 | [53] | 2024 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| 32 | [55] | 2024 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| 33 | [56] | 2024 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ref. | Year | City | Country | Tool/Assessment Method | Parameters Assessed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [1] | 2024 | Hong Kong | China | GIS, Walk Score, accessibility tools | Proximity, Accessibility, Walkability, Urban Services |

| 2 | [3] | 2024 | Cagliari, Perugia, Pisa, Trieste | Italy | Urban Morphology, GIS | Accessibility, Morphological Features, Walkability |

| 3 | [5] | 2023 | Various Italian Cities | Italy | Next Proximity Index (based on open data) | Proximity, Accessibility, Open Data Analysis |

| 4 | [9] | 2022 | Not specific (urban China) | China | Urban Heat Adaptation Framework | Urban Climate Adaptability |

| 5 | [17] | 2022 | Guangzhou | China | GPS Trajectory Data | Mobility, Traffic Exposure, Individual Movement Patterns |

| 6 | [18] | 2021 | Multiple cities in the US | USA | Longitudinal Mobility Study using Mobile & GIS Data | Pandemic Impact on Movement & Access |

| 7 | [20] | 2024 | Surabaya | Indonesia | Urban morphology, policy review | Proximity, spatial layout |

| 8 | [14] | 2022 | General (India) | India | Geospatial analysis | Micro-mobility, access time |

| 9 | [56] | 2024 | Surakarta | Indonesia | Big Data, GIS | Green space accessibility |

| 10 | [24] | 2019 | Urban China | China | GIS, walkability index | Walkable neighborhoods, inequality |

| 11 | [26] | 2021 | Cagliari | Italy | GIS, reuse potential (Porosity, Crossing, etc.) | Reuse of public buildings |

| 12 | [32] | 2022 | Barcelona | Spain | Pedestrian travel time, GIS | Accessibility and proximity via walk times |

| 13 | [35] | 2023 | Oslo, Lisbon | Norway, Portugal | Case studies, planning analysis | Remote workspaces, mixed-use planning |

| 14 | [34] | 2024 | Oslo | Norway | Accessibility modelling, travel distance | 15-minutes city accessibility in Oslo |

| 15 | [36] | 2023 | Rome, London, Paris | Italy, UK, France | Graph theory and spatial network analysis | Comparative network-based accessibility |

| 16 | [25] | 2021 | Naples, London | Italy, UK | Accessibility analysis using GIS | Comparative analysis of neighborhood accessibility |

| 17 | [48] | 2023 | Beijing | China | Post-pandemic urban analysis, spatial mapping | Living circle analysis under an epidemic context |

| 18 | [49] | 2023 | Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei | China | GIS and visual analysis | 15-minutes facility distribution |

| 19 | [43] | 2024 | Terni, Matera | Italy | Configurational urban analysis | Urban quality through a 15-minutes city lens |

| 20 | [45] | 2022 | Palermo | Italy | Urban policy and spatial design analysis | Palermo’s structure in the 15-minutes context |

| 21 | [46] | 2023 | Sicily | Italy | Case study analysis (COVID-19 period) | COVID-19 effects on proximity and service access |

| 22 | [47] | 2023 | Montréal | Canada | Behavioral surveys, urban lifestyle analysis | Behavioral perspective on 15/30-minutes city lifestyles |

| 23 | [37] | 2022 | Turin | Italy | Service accessibility measurement | Access to services in a 15-minutes city framework |

| 24 | [39] | 2024 | Auckland | New Zealand | GIS-based spatial analysis Custom indexes: Porosity, Crossing, Attractiveness | Spatial connectivity, Accessibility of services, Urban morphology and walkability |

| 25 | [33] | 2023 | Montréal | Canada | Accessibility metrics by travel purpose Mode-based spatial analysis | Travel time to key services, Mode-based access differences (e.g., walk, cycle, transit), Functional diversity and proximity, |

| 26 | [38] | 2023 | Dubai | UAE | GIS-based service area mapping Walkability analysis | Walking distance to services, Spatial distribution of services, Service coverage efficiency |

| 27 | [51] | 2022 | Paris, Barcelona, Milan | France, Spain, Italy | Comparative urban spatial analysis, Morphological and functional indicators | Proximity of daily service, Urban density, and land-use mix Human-scale design and public space integration |

| 28 | [52] | 2020 | Lombardy | Italy | Chrono-urbanism (time-based spatial assessment), Station catchment area analysis | Access to urban functions via railway stations, Temporal proximity of daily needs, Transport-oriented spatial planning |

| 29 | [41] | 2022 | Krakow | Poland | GIS-based spatial analysis | Proximity to services, walking coverage, and service distribution |

| 30 | [31] | 2022 | Naples | Italy | GIS, network analysis | Accessibility index, spatial equity, 15-minutes walking coverage |

| 31 | [40] | 2021 | Bogotá | Colombia | Mobility & behavior surveys, temporal analysis | Mobility change, activity patterns, and access to daily needs |

| 32 | [55] | 2024 | Tallinn | Estonia | Two-level GIS spatial analysis | Urban + expansion area service proximity, suitability mapping |

| 33 | [53] | 2024 | Hamilton | New Zealand | GIS, catchment mapping, mobility analysis | Accessibility to services, multimodal coverage, and equity |

References

- Liu, D.; Kwan, M.-P.; Wang, J. Developing the 15-Minute City: A comprehensive assessment of the status in Hong Kong. Travel Behav. Soc. 2024, 34, 100666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgante, B.; Patimisco, L.; Annunziata, A. Developing a 15-minute city: A comparative study of four Italian Cities-Cagliari, Perugia, Pisa, and Trieste. Cities 2024, 146, 104765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z.; Moreno, C.; Chabaud, D.; Pratlong, F. The Palgrave Handbook of Global Sustainability; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Olivari, B.; Cipriano, P.; Napolitano, M.; Giovannini, L. Are Italian cities already 15-minute? Presenting the Next Proximity Index: A novel and scalable way to measure it, based on open data. J. Urban Mobil. 2023, 4, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarin, G.; MacLeavy, J.; Manley, D. Rethinking urban utopianism: The fallacy of social mix in the 15-minute city. Urban Stud. 2023, 60, 3167–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fronczak, M. 15-Minute City-Genesis-Inspiration-Realisation. Introduction to Research in a Form of Overview; Przestrzeń Urbanistyka Architektura: Kraków, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, C.; Gall, C.; Chabaud, D.; Garnier, M.; Illian, M.; Pratlong, F. The 15-Minute City Model: An Innovative Approach to Measuring the Quality of Life in Urban Settings 30-Minute Territory Model in Low-Density Areas WHITE PAPER N° 3; IAE Paris-Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; He, B.-J. Development of a framework for urban heat adaptation in 15-minute city. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wolański, M. The potential role of railway stations and public transport nodes in the development of “15-minute cities”. Infrastructures 2023, 8, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukouras, E. The question of proximity. Demographic ageing places the 15-minute-city theory under stress. Authorea Preprints 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, E.; Sdoukopoulos, A.; Politis, I. Measuring compliance with the 15-minute city concept: State-of-the-art, major components and further requirements. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L. An analysis of the role of 15-minute cities in developing countries. Interdiscip. Humanit. Commun. Stud. 2024, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Bhattacharya, D.; Chaturvedi, A.; Singh, N. Assessing micro-mobility services in pandemics for studying the 10-minutes cities concept in India using geospatial data analysis: An application. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM SIGSPATIAL International Workshop on Computational Transportation Science, Seattle, WA, USA, 1 November 2022; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Sharifi, A.; Hajian Hossein Abadi, M.; Moradi, Z. From garden city to 15-minute city: A historical perspective and critical assessment. Land 2023, 12, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z.; Bibri, S.E.; Chabaud, D.; Moreno, C. The ‘15-Minute City’concept can shape a net-zero urban future. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, Z.; Kwan, M.-P.; Liu, D.; Tang, L.; Chen, Y.; Fang, M. Assessing individual activity-related exposures to traffic congestion using GPS trajectory data. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 98, 103240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kwan, M.-P. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people’s mobility: A longitudinal study of the US from March to September of 2020. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 93, 103039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozoukidou, G.; Chatziyiannaki, Z. 15-Minute City: Decomposing the New Urban Planning Eutopia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiansa, A.; Navastara, A.; Yusuf, M.; Ramadhan, M.; Akbar, R. From 15-minutes city to proximity paradigm: Insights from surabaya rungkut development unit. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, T.; Farber, S.; Manaugh, K.; El-Geneidy, A. Assessing the readiness for 15-minute cities: A literature review on performance metrics and implementation challenges worldwide. Transp. Rev. 2025, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Sharifi, A.; Sadeghi, A. The 15-minute city: Urban planning and design efforts toward creating sustainable neighborhoods. Cities 2023, 132, 104101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozoukidou, G.; Angelidou, M. Urban planning in the 15-minute city: Revisited under sustainable and smart city developments until 2030. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 1356–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, M.; Ding, N.; Li, J.; Jin, X.; Xiao, H.; He, Z.; Su, S. The 15-minute walkable neighborhoods: Measurement, social inequalities and implications for building healthy communities in urban China. J. Transp. Health 2019, 13, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglione, F.; Gargiulo, C.; Zucaro, F.; Cottrill, C. 15-minute neighbourhood accessibility: A comparison between Naples and London. Eur. Transp. 2021, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balletto, G.; Ladu, M.; Milesi, A.; Borruso, G. A methodological approach on disused public properties in the 15-minute city perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. The Fifteen Minute Vision: Future Proofing Our Cities. 2024. Available online: https://www.arup.com/en-us/insights/the-fifteen-minute-vision-future-proofing-our-cities/ (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Allam, Z.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Chabaud, D.; Moreno, C. The 15-minute city offers a new framework for sustainability, liveability, and health. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e181–e183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Kwan, M.-P.; Kan, Z.; Wang, J. Toward a healthy urban living environment: Assessing 15-minute green-blue space accessibility. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, T.; Hobbs, M.; Conrow, L.; Reid, N.; Young, R.; Anderson, M. The x-minute city: Measuring the 10, 15, 20-minute city and an evaluation of its use for sustainable urban design. Cities 2022, 131, 103924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglione, F.; Gargiulo, C.; Zucaro, F.; Cottrill, C. Urban accessibility in a 15-minute city: A measure in the city of Naples, Italy. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Ortiz, C.; Marquet, O.; Mojica, L.; Vich, G. Barcelona under the 15-minute city lens: Mapping the accessibility and proximity potential based on pedestrian travel times. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negm, H.; Miller, H.; El-Geneidy, A. Exploring the X-Minute City by Travel Purpose in Montréal, Canada. Findings 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrami, M.; Sliwa, M.W.; Rynning, M.K. Walk further and access more! Exploring the 15-minute city concept in Oslo, Norway. J. Urban Mobil. 2024, 5, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marino, M.; Tomaz, E.; Henriques, C.; Chavoshi, S.H. The 15-minute city concept and new working spaces: A planning perspective from Oslo and Lisbon. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2023, 31, 598–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, L.; D’Autilia, R.; Marrone, P.; Montella, I. Graph representation of the 15-minute city: A comparison between Rome, London, and Paris. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staricco, L. 15-, 10-or 5-minute city? A focus on accessibility to services in Turin, Italy. J. Urban Mobil. 2022, 2, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Ali, T.; Gawai, R.; Elaksher, A. Fifteen-, Ten-, or five minute city? Walkability to services assessment: Case of Dubai, UAE. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Qiao, W.; Chuang, I.-T.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Beattie, L. Mapping liveability: The “15-min city” concept for car-dependent districts in Auckland, New Zealand. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 163, 103197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, L.A.; Arellana, J.; Oviedo, D.; Aristizábal, C.A.M. COVID-19, activity and mobility patterns in Bogotá. Are we ready for a ‘15-minute city’? Travel Behav. Soc. 2021, 24, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noworól, A.; Kopyciński, P.; Hałat, P.; Salamon, J.; Hołuj, A. The 15-Minute City—The geographical proximity of services in Krakow. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoina, M.; Voukkali, I.; Anagnostopoulos, A.; Papamichael, I.; Stylianou, M.; Zorpas, A.A. The 15-minute city concept: The case study within a neighbourhood of Thessaloniki. Waste Manag. Res. 2024, 42, 694–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgante, B.; Valluzzi, R.; Annunziata, A. Developing a 15-minute city: Evaluating urban quality using configurational analysis. The case study of Terni and Matera, Italy. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 162, 103171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelfattah, L.; Deponte, D.; Fossa, G. The 15-minute city: Interpreting the model to bring out urban resiliencies. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezer, E. 15 Minute City Concept. A Glance at the Palermo Case Study. Riv. Dottorato Ric. Archit. Arti Pianif. Dell’università Studi Palermo-Dip. Archit. 2022, 21, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Basbas, S.; Campisi, T.; Papas, T.; Trouva, M.; Tesoriere, G. The 15-minute city model: The case of sicily during and after COVID-19. Komunikácie 2023, 25, A83–A92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkenfeld, C.; Victoriano-Habit, R.; Alousi-Jones, M.; Soliz, A.; El-Geneidy, A. Who is living a local lifestyle? Towards a better understanding of the 15-minute-city and 30-minute-city concepts from a behavioural perspective in Montréal, Canada. J. Urban Mobil. 2023, 3, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C. A 15-minute Living Circle from the Perspective of Epidemic and Post-epidemic Cities-the Case of Beijing. SHS Web Conf. 2023, 163, 04001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Visualizing and assessing the 15-minute city facility configuration of city region A study on the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Urban Agglomeration. Adv. Educ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Res. 2023, 4, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D. Examination of the 15-minute life cycle program of a Chinese mega city: Case study of Guangzhou. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 238, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, F.; Radicchi, A. La prossimità nei progetti urbani: Una analisi comparativa fra Parigi, Barcellona e Milano. Techne 2022, 23, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Donno, M. The 15 Minutes City: A Case Study of Chrono-Urbanism Applied to the Lombardy Railway Stations. Master’s Thesis, Scuola di Ingegneria Industriale e dell’Informazione, Milan, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Chuang, I.-T.; Qiao, W.; Jiang, J.; Beattie, L. Evaluating the 15-minute city paradigm across urban districts: A mobility-based approach in Hamilton, New Zealand. Cities 2024, 151, 105147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchigiani, E.; Bonfantini, B. Urban transition and the return of neighbourhood planning. Questioning the proximity syndrome and the 15-minute city. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffaree Pour, N.; Partanen, J. Planning for the urban future: Two-level spatial analysis to discover 15-Minute City potential in urban area and expansion in Tallinn, Estonia. J. Comput. Soc. Sci. 2024, 7, 777–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musyary, M.D.; Perdana, A.B.; Mantali, Z.; Gayo, A.P.A.; Muhtadin, R.; Alma, Z. Use of big data in implementing the 15-minutes city concept in Indonesia (Case study: Providing ideal locations for public green open space in the city of Surakarta). Rev. Contemp. Philos. 2024, 23, 71–94. [Google Scholar]

| Concept | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Content | Articles published between 2019 and 2024. Answers the research question Papers containing at least one relevant keyword related to the 15 MC concept. Focus on urban planning, policy discourse, and implementation of the 15 MC model. | Non-English language papers were removed. Papers that did not have titles and abstracts relevant to the core research questions were excluded. Full-text screening further eliminated papers that only mentioned the 15 MC concept without directly engaging with it in a meaningful way. |

| Article type | Academic: empirical, peer-reviewed articles. Conference papers Grey literature, including case studies from reputable sources | Blogs Editorials Commentary Media Secondary research |

| Geographical focus | Developing countries, LMICs [World Bank criteria] HICs [World Bank criteria] |

| City | GIS Spatial Analysis | Walkability Index [Walk Score] | Mixed-Use Development Analysis | Transport Network Analysis [Public Transport Accessibility Index] | Urban Morphology [Space Syntax] | Cycling Infrastructure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paris | High service accessibility mapping [33] | 98 [High] | Strong mixed-use zoning | Metro, tram, bus, well-integrated [2] | Compact urban form [2] | Extensive bike lanes, bike-sharing system [2] |

| Milan | Service accessibility mapping in urban studies [5] | 85 [High] | High-density mixed-use zoning [5] | Metro, trams, and buses are well-connected [5] | Compact historical core with expanding modern zones [5] | Strong investments in cycling lanes [5] |

| Melbourne | Not specifically used in GIS tools | 92 [High] | Mixed-use zoning is integrated in new developments [12] | Not discussed | Not discussed | Expanding bike lanes and infrastructure [19] |

| Lagos | Limited GIS accessibility mapping [13] | 50 [Low] | Highly informal settlement areas lack structured mixed-use planning [13] | Public transport lacks integration [13] | High-density, unstructured urban expansion [13] | Very limited cycling infrastructure [13] |

| Mumbai | Inconsistent service accessibility [14] | 58 [Low] | Limited mixed-use planning [14] | High-density rail, poor last-mile connectivity [14] | Unstructured, informal settlements [14] | Weak cycling infrastructure [14] |

| Portland | Not specifically used in GIS tools | 89 [High] | Mixed-use zoning policies implemented [19] | Not discussed | Not discussed | Not discussed |

| Jakarta | Limited GIS application [21] | 65 [Medium] | Some mixed-use developments but lack consistency [21] | Bus rapid transit, weak metro system [21] | High-density urban sprawl [21] | Few dedicated bike lanes [21] |

| Shanghai | GIS urban mobility analysis [24] | 87 [High] | High urban density supports mixed-use zoning [24] | Extensive metro network [24] | Dense urban core [24] | Growing cycling infrastructure, but still car-reliant [24] |

| London | Used in transport and accessibility analysis [25] | 94 [High] | Mixed-use development strategies applied [25] | Well-integrated transit system [25] | Polycentric urban layout [25] | London Cycleways program improving connectivity [25] |

| Bogotá | GIS-based cycling and transit analysis [31] | 75 [Medium] | Strong community-based planning [31] | BRT system is well-developed [31] | Polycentric urban structure [31] | Expanding bike lanes, urban cycling culture [31] |

| Naples | Limited application [31] | 78 [Medium] | Unstructured mixed-use zoning [31] | Moderate public transport efficiency [31] | Fragmented urban morphology [31] | Weak cycling infrastructure [31] |

| Barcelona | GIS-based analysis for superblocks [32] | 90 [High] | Strong mixed-use model [32] | Metro and BRT systems integrated [32] | Compact grid layout [32] | Superblocks prioritize pedestrian and cycling mobility [32] |

| Oslo | Public transport-oriented GIS mapping | 95 [High] | High integration of mixed-use neighborhoods [34] | Strong metro, tram, and bus connectivity [34] | Compact city design [35] | Extensive cycling lanes, investments in bike-sharing [34] |

| Lisbon | Spatial accessibility mapping applied [35] | 88 [High] | Moderate mixed-use zoning [35] | Moderate metro and bus network [35] | Historic core limits transformation [35] | Expanding cycling network but still underdeveloped [35] |

| Rome | Not specifically used in GIS tools | 80 [Medium] | Mixed-use policies improving accessibility [36] | Not discussed | Not discussed | Not discussed |

| Turin | GIS-based spatial planning tools applied [37] | 82 [Medium-High] | Mixed-use zoning improves accessibility [37] | Moderate public transport efficiency [37] | Well-structured central layout [37] | Expanding cycling network [37] |

| Dubai | GIS used in transport analysis [38] | 64 [Medium-Low] | Gated communities hinder mixed-use integration [38] | High reliance on car-based transport [38] | Urban expansion challenges proximity planning [38] | Limited cycling infrastructure, improving policies [38] |

| Auckland | GIS applied in walkability and proximity studies [39] | 70 [Medium-High] | Moderate mixed-use zoning [39] | Public transport efficiency varies by district [39] | Car-dependent suburban areas impact morphology [39] | Cycling infrastructure is expanding, but unevenly distributed [39] |

| Tallinn | Spatial analysis for 15 MC assessment [40] | 80 [Medium-High] [40] | Improving mixed-use urban development [40] | Expanding the bus and tram network [40] | Compact city design [40] | Growing cycling infrastructure, but still developing [40] |

| Krakow | Used in urban accessibility research [41] | 77 [Medium] | Moderate mixed-use zoning [41] | Tram-based public transport [41] | Historic core limits accessibility improvements [41] | Low cycling infrastructure, improving gradually [41] |

| Thessaloniki | GIS applied in accessibility mapping [42] | 72 [Medium] | Mixed-use developments emerging [42] | Bus-dominant public transport [42] | Historic layout limits transformation [42] | Growing cycling network [42] |

| Aspect | Developed Countries [e.g., Paris, Melbourne, Portland, Oslo] | Developing Countries [e.g., Mumbai, Jakarta, Lagos, Surabaya] |

|---|---|---|

| Urban Infrastructure | Well-planned, existing pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods, extensive cycling infrastructure [2,37] | Unplanned urban sprawl, weak cycling and pedestrian infrastructure, reliance on cars [19,20] |

| Governance and Policy | Strong zoning laws, integrated public transport, and sustainability-focused urban planning [36] | Weak enforcement of zoning laws, informal settlements, and limited funding for infrastructure [13,21] |

| Public Transportation | High public transit efficiency, multimodal connectivity, and investments in green transport [18] | Underdeveloped or overcrowded public transport, informal modes [rickshaws, minibuses] dominate [46] |

| Proximity and Accessibility | Most services within a 15-minutes walking or cycling distance, high accessibility score [24] | Services may require 20–30 min due to congestion, lack of mixed-use zoning [13,47] |

| Socio-Economic Barriers | Gentrification risks, rising housing costs near accessible hubs [6] | High economic inequality, informal housing, poor service distribution [38] |

| Adaptation Strategies | Expansion of pedestrian zones, cycling lanes, and smart mobility [15] | Incremental improvements to community-led projects, micro-mobility solutions [21,53] |

| Challenge | Scientific Debate & Challenges | Key Studies, Perspectives, and Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Gentrification & Socioeconomic Exclusion | Critics argue that the 15 MC model can lead to gentrification, pricing out low-income residents from well-connected areas. While proximity increases livability, it can also exacerbate socio-economic divides, as seen in Paris and Barcelona. There is an ongoing debate on whether rent control or subsidized housing can mitigate displacement risks. | Ref. [6]—The 15 MC creates “exclusive proximity” where only high-income residents benefit from walkability. [32] Superblock initiatives in Barcelona incorporate social housing policies to counteract displacement. |

| Infrastructure Constraints in Developing Cities | Many developing cities lack the infrastructure to implement the 15 MC model due to poor road networks, informal settlements, and a lack of planning frameworks. The scientific debate centers on whether this model can be adapted to informal urban areas or if a 20- or 30-min model is more realistic. | [20] A “10 min city” model was tested in India, showing that shorter proximity models can be successful in dense areas. [21] Studied Surabaya’s urban expansion, showing how micro-infrastructure projects help integrate informal areas. |

| Car Dependency & Urban Sprawl | Cities with urban sprawl and low-density suburbs struggle with the 15 MC model due to long travel distances. There is a scientific divide on whether retrofitting suburbs for walkability is feasible or if transport-oriented solutions are a better alternative. | [34] Found that in Oslo, transit-oriented developments helped suburban areas meet 15-minutes criteria. [46] Argued that in Auckland, a hybrid 30-min city model is more practical due to car dependency. |

| Land-Use & Zoning Barriers | Rigid zoning laws in some cities prevent mixed-use developments, making the 15 MC hard to implement. Scientific debate focuses on whether existing zones should be reformed or if new urban developments should be built instead. | [12] Found that in Athens, mixed-use zoning regulations improved urban mobility. [18] Suggest “soft zoning” policies that encourage gradual transitions to mixed-use neighborhoods. |

| Digital Divide & Smart Mobility | The digital divide makes it harder for some residents [especially elderly and low-income populations] to access smart mobility services. - Some researchers argue that digital tools enhance accessibility, while others warn that they may increase exclusion. | [8] Advocated for a “hybrid mobility” approach that integrates digital tools with traditional urban planning. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iqbal, A.; Nazir, H.; Qazi, A.W. Exploring the 15-Minutes City Concept: Global Challenges and Opportunities in Diverse Urban Contexts. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9070252

Iqbal A, Nazir H, Qazi AW. Exploring the 15-Minutes City Concept: Global Challenges and Opportunities in Diverse Urban Contexts. Urban Science. 2025; 9(7):252. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9070252

Chicago/Turabian StyleIqbal, Asifa, Humaira Nazir, and Ammad Waheed Qazi. 2025. "Exploring the 15-Minutes City Concept: Global Challenges and Opportunities in Diverse Urban Contexts" Urban Science 9, no. 7: 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9070252

APA StyleIqbal, A., Nazir, H., & Qazi, A. W. (2025). Exploring the 15-Minutes City Concept: Global Challenges and Opportunities in Diverse Urban Contexts. Urban Science, 9(7), 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9070252