To accomplish that, instead of attempting to rigidly criticise the concept of security in public space, this text adopts a Foucauldian perspective to analyse how its ambiguity can contribute to urban governance processes [

33]. Foucault’s concept of security is deeply rooted in his broader theoretical framework of power, governance, and biopolitics [

34]. Distinct from traditional notions of sovereignty and discipline, in Foucault’s view, security operates through mechanisms of regulation and optimisation, shaping social realities rather than imposing rigid controls. He states that in the case of security, “the objective is to plan an environment based on a series of possible events” [

34]; here, control becomes inherent in spatial planning when security is prioritised. However, security opens up an internal controversy when juxtaposed with public space: efforts to enhance security inevitably involve social control measures. At the heart of Foucault’s perspective is the

dispositif of security, a set of strategies and institutions that govern through anticipation, modulation, and facilitation, rather than direct coercion [

33]. This regards a heterogeneous system comprising discourses, institutions, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific statements, philosophical propositions, and moral frameworks. Unlike juridical or disciplinary systems that impose strict control, the security

dispositif is a flexible formation that emerges in response to pressing societal needs, adapting to specific historical and spatial frameworks, which Foucault terms the milieu. Unlike the territory of sovereignty, which is to be conquered and defended, or the closed space of discipline, which is structured and controlled, the milieu is an open, dynamic space designed to facilitate movement and circulation. Here, security does not seek to prohibit or confine but rather to organise circulation of people, goods, and risks—eliminating threats, distinguishing between beneficial and harmful flows [

33], and maximising the former while minimising the latter. The milieu of security refers to a series of possible events and the uncertainty that must be integrated into given spaces [

35,

36]. Foucault further emphasises that security evolves: while early forms of governance sought to contain and structure, modern security strategies aim to expand, regulate, and facilitate flows. The author claimed that modern security apparatuses do not aim to discipline or confine, but rather to manage and optimise flows and circulations within a

milieu acknowledging the uncertainty and unpredictability of urban life, while still seeking to preserve its freedom and vitality. This transition reflects a broader transformation in power relations, where control is exercised not through rigid enforcement but through flexible, anticipatory situated governance mechanisms that shape the conditions of possibility within which events unfold.

3.1. Eu Approaches to Urban Security

The EU has adopted a dual approach, implementing both measures to enhance security and initiatives to preserve the openness of public spaces. Initiatives such as the security-by-design principles and a new counter-terrorism agenda for the EU aim to incorporate risk awareness in the planning of public spaces rather than strengthen control.

The European Union’s approach to urban safety and security, particularly addressing terrorism threats, has evolved significantly over the last five decades. In the 1970s and 1980s, Europe faced domestic terrorism threats from groups like the IRA and ETA. However, the post-9/11 era marked a major shift, with EU institutions strengthening cooperation on counterterrorism through intelligence-sharing, border control measures, and coordinated security policies [

37]. Following the Madrid (2004) and London (2005) bombings, the EU adopted the Counterterrorism Strategy [

39], focusing on four pillars: prevent, protect, pursue, and respond. The 2015–2016 wave of terrorist attacks in Paris, Brussels, and Nice prompted additional measures, including stricter Schengen border controls, stronger cybersecurity measures, and improved urban security planning to protect public spaces: as far as border controls are concerned EU Justice and Home Affairs ministers met on 20 November and agreed to strengthen external Schengen border checks—including systematic screening of all travellers (EU citizens and non-citizens), biometric verification, connection to Interpol databases, and enhanced Frontex and Europol cooperation—to be implemented by March 2016 and France temporarily reinstated its national borders after the Paris attacks and maintained those controls “as long as the terrorist threat requires us to do so,” putting additional road checkpoints in place. As for cybersecurity side, the EU 2016 General Report highlights reinforced efforts in cybersecurity and counter-terrorism, including tightening online radicalization prevention, collaboration with major tech platforms, and establishing the EU Internet Referral Unit under Europol to remove extremist content; also, following the attacks, the EU Internet Forum was created to bring together industry and law enforcement to tackle terrorist material online. Urban security improvements took place mainly in Belgium, after the March 2016 Brussels bombings: the national government elevated its terror alert to level 4 and launched “Operation Vigilant Guardian,” deploying the military to patrol “soft targets” like metro stations (increasing baggage screening, and introducing security technology like body scanners, metal detectors, and more CCTV, broadening urban protections on public transport) and public spaces.

Today, the EU prioritises a comprehensive approach, balancing security with urban design that maintains accessibility and social interaction. Several EU regulations and guidelines support urban safety and anti-terrorism efforts, including the Urban Agenda for the EU—Security in Public Spaces Partnership [

40] and the European Security Union Strategy [

41]. These policies outline the need for preventive measures and effective response mechanisms that integrate security, openness, aesthetics, liveability, accessibility, and public well-being within urban systems and public spaces, while considering their diverse characteristics. They also extend to fostering cooperation among stakeholders at various levels, aiming to raise awareness of risk-related aspects and their integration into security processes, concerning new threats (such as cyberterrorism).

Among these, the security-by-design approach (SBD) [

25] emerges as a fruitful synthetic strategy to integrate the various components of public life and its protection to threads. Promoted and supported by the European Commission, the SBD approach refers to mitigating threats of human origin (criminal actions, illegal behaviour, or terrorist attacks) through intrinsic structural features of a public space or its surrounding environment, often, but not always, from its foundational phase.

The objective is to embed protective interventions into the design of public spaces in a manner that maintains both functionality and aesthetic quality [

25]. Ideally, these preventive or protective elements are part of the initial design of a public space, but they can also be integrated later.

SBD is also a multidisciplinary approach that involves a vast diversity of actors in the urban space: architects, urban planners, law enforcement agencies (LEAs), engineers, municipal staff, emergency services, and other entities.

The four key principles that define the approach are as follows:

Proportionality: security measures should be balanced according to the risks being addressed, minimising their impact on daily social and economic activities.

Multifunctionality: security principles should be considered (and applied) from the early stages of design or redesign, leading to integrated, multifunctional, economic and aesthetically high-quality solutions.

Stakeholder cooperation: various stakeholders (authorities, architects, designers, police, security specialists, civil society, etc.) are considered essential for high-quality public spaces equipped with well-designed and should be called to collaborate to develop effective security solutions.

Aesthetic design: security solutions should be seamlessly integrated into the morphology/design of public spaces, combining comfort, usability, and functionality while avoiding intrusiveness or inducing fear and anxiety in society.

EC’s SBD guidelines are directed at operators and public authorities and cover four main areas: assessment and planning, awareness and training, physical protection of spaces, and cooperation.

The first area emphasises the importance of preventive actions by conducting vulnerability assessments, security plans, and crisis management strategies, alongside the appointment and proper training of specific personnel responsible for coordination and security measures. This category includes initiatives to integrate anti-terrorism design principles and CPTED [

14,

20] into urban planning to enhance security in high-risk areas. From a management perspective, adopting a proportionality-based strategy may involve reorganising site elements, such as separating public and private activities and minimising vehicular access points to control movement within urban areas. In these designated areas, communication protocols and decision-making models—such as JESIP (Joint Emergency Services Interoperability Principles) in the United Kingdom or Oslo’s emergency response framework—can be established to improve inter-agency coordination in crises. This definition includes all “incidents” or emergencies (regardless of their causes-natural, individual, terroristic) that may potentially damage people: these protocols also include digital tools (Apps, guided flowcharts) that enable responding agencies to build a shared situation awareness and framing from the very beginning.

The second area focuses on public awareness campaigns to educate people on recognising suspicious behaviour and responding to sudden security threats in public spaces or events, fostering a general security culture. Enhancing emergency preparedness through training and simulation exercises has helped internalise procedures, building a “muscle memory” for situational awareness among security personnel and first responders to ensure swift and coordinated action in emergency scenarios. Projects like Project Griffin in London [

6] were pioneering in bringing together the police, emergency services, local authorities, and the private security sector to coordinate efforts through training to disrupt hostile reconnaissance and support operations in response to terrorist activity.

The third area concerns integrating security considerations into the early stages of designing new structures or events in public spaces, aimed at responding concretely to the growing demand for security and social interaction, as well as the freedom of expression by citizens. This approach often struggles to find full operational implementation, particularly in local or small-scale interventions entrusted to municipalities, which tend to favour “strong” security measures [

33]. An example is Barcelona’s “Security in Public Spaces” Approach [

40]: the city combines discreet security infrastructure (e.g., urban furniture as protection) with community engagement programmes and the “superblocks” model prioritises pedestrian-friendly, accessible, and socially engaging spaces. Hybrid Governance Models can also be explored, combining government security policies with local participation and urban design strategies. The Netherlands’ “Safe and Open Cities” approach in Rotterdam and Amsterdam [

42], for example, integrated preventive policing, social outreach programmes, and urban design solutions to promote safety while maintaining an open public realm. In many cases, these measures are added later in the process, without engaging in a redesign or even partial adaptation of the site. This lack of real integration with the specific urban context risks negatively affecting these spaces’ perception, liveability, and collective nature.

The fourth aspect—cooperation—addresses clarifying roles and responsibilities in public–private security cooperation, enhancing local, regional, and national coordination, improving communication, facilitating information-sharing, and promoting the exchange of best practices and practical recommendations [

40]. The creation of “communities of practice,” networks formed with an explicit focus on problem-solving, knowledge exchange, and “discourse coalitions” within a specific location, can facilitate collaboration between different interests, creating a shared framework [

21].

The EC proposed approach, however, tends to provide reduced space for urban adaptation, leaving individual security forces (police or other enforcement) to organise security and this way denying the principles of dynamic/open milieu that shape a flexible, anticipatory Foucauldian governance. An approach that ensures coordinated reactions to urban threats and encourages research on urban security.

3.2. Balancing Security and Sociality in Public Spaces: The SAFE CITIES Approach

In the framework of the SBD optimisation, the SAFE CITIES project (GA 101073945) was financed to develop a set of tools that supports local authorities, space and facility managers, practitioners, first responders in planning and managing temporary public spaces, such as sport games, markets, shopping malls, festivals, music or cultural events. Specifically, SAFE CITIES worked considering a wide range of public spaces and the planned or ordinary events and activities that take place there: business spaces (hotels, large office spaces, conferences), cultural spaces (concert hall, museum, monuments, sport events, stadiums, amusement parks, tourist sites, etc.), institutional spaces (public buildings, healthcare buildings, education buildings), nightlife areas (high density of bars, pubs and/or nightclubs, restaurants, coffee shops, small concert halls), religion/worship spaces (churches, mosques, etc.), shopping areas (malls, main shopping streets in city centres), vibrant public squares (where many events take place, next to important buildings, that have regular big markets, festivals, etc.) and transport hubs (train station, bus hub, underground metro stations, airports, etc.).

The project adopted a multi-disciplinary approach to integrating urban security principles with adaptive urban planning while adhering to the design-for-all philosophy. Its primary objective was to test the potential harmonisation of security measures with urban planning strategies, ensuring that public safety and well-being are seamlessly embedded into the city’s fabric. This approach promotes the development of public spaces that are not only secure but also welcoming and accommodating, where safety and accessibility address the intersectional needs of all community members, regardless of age, ability, or background. To achieve this, the project involved a comprehensive assessment of public spaces, considering their societal role, urban planning and design challenges, and physical conditions. Among the project results is a security and vulnerability (SVA) assessment framework supported by an interactive platform that helps municipalities, planners, and urban security stakeholders to include and consider different dimensions into an SBD framework.

This methodology should prove particularly useful in organising the security governance of spaces, as well as in connection with national regulations and the local division of roles for planning, security management, and active protection. This approach, precisely with the idea of creating a balance between logistical and regulatory aspects and those related to management and sociality, places a special emphasis on the involvement of citizens and stakeholders, identified by the term Local Citizens Networks (LCN). LCNs are expected to contribute to various project activities, including SVA, validation, and awareness raising. The aim is to strengthen a culture of safety and security in public spaces, ensuring the optimisation of social and spatial solutions to be embraced by both security stakeholders and civil society, not to compromise the vibrancy of social life.

The participation in the SAFE CITIES activities allowed the authors to refine some insights related to the Foucauldian vision of security, emphasising the management of uncertainty, not by eliminating threats but organising social and environmental conditions to sustain and enhance the dynamic processes that constitute public spaces’ dynamics. In this avenue, the approach developed by the project incorporated different potential approaches: engaging local stakeholders in planning how spaces are secured, involving them in devising response strategies but also investigate risk perception and possible individual and group tolerance of restrictive measures, and work on communication actions (the so called third tier–information circle) that may involve citizens and stakeholders with low levels of relevance and interest, primarily focused on ensuring transparency and openness to the community.

3.2.1. The SAFE CITIES Atlas

To incorporate these assumptions and suggestions, the SAFE-CITIES project has developed a decision-supporting tool named Atlas 4 Safe Public Spaces Design Guiding Framework. The Atlas is an operational tool to assess the socio-technical aspects of urban spaces that may not be considered in traditional security evaluation tools. The Atlas is inspired by the NEB Compass methodology [

43] of the New European Bauhaus.

The NEB Compass [

44] is a multi-criteria assessment and guidance tool developed to operationalise the core values of the New European Bauhaus (NEB) initiative—sustainability, aesthetics, and inclusion—within the design and regeneration of architecture and public spaces. Introduced in 2020 by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, the NEB is a flagship initiative that aligns with the EU Green Deal, aiming to foster environmental transformation and social and cultural renewal in European cities. The Compass provides a structured framework to valorise and assess design practices contributing to these goals. The Compass was developed to enable practitioners, policymakers, and communities to evaluate how proposed or existing urban spaces contribute to climate action (e.g., circular economy, biodiversity, pollution reduction), to the aesthetic and experiential quality of spaces (i.e., beauty beyond functionality), and social inclusion (e.g., accessibility, affordability, and cultural diversity) (

Figure 1). The tool supports the idea that these three pillars are interdependent and should not be pursued in isolation. A distinctive feature of the NEB framework is its coupling of security and inclusiveness—viewing both not as competing concerns, but as mutually reinforcing imperatives. Rather than imposing obtrusive or alienating security interventions, the adoption and transformation of the NEB Compass into the Atlas allowed to encourage embedded solutions, preserving openness while addressing real risks and interpreting the NEB Compass not merely a design checklist but a transformative lens through which the quality, resilience, and democratic nature of urban spaces can be evaluated and enhanced shaped the premises of the Atlas creation.

The Atlas aims to serve as a comprehensive tool for integrating security into urban design while maintaining a balance between safety, aesthetics, and social functionality. It was developed to address the socio-technical dimensions of urban spaces often overlooked in conventional security assessment methodologies. By extending beyond purely physical considerations, the Atlas provides a more holistic evaluation of security challenges and solutions in public spaces.

Functioning as a strategic “compass” for security-by-design interventions, the Atlas offers practical guidance to urban planners, designers, and policymakers on implementing security measures that are seamlessly embedded within the urban landscape. A core objective is to support decision-makers in translating the values of the New European Bauhaus—beauty, sustainability, and inclusion—into actionable strategies within urban security frameworks. This ensures that protective measures enhance safety and contribute to the overall quality and liveability of public spaces.

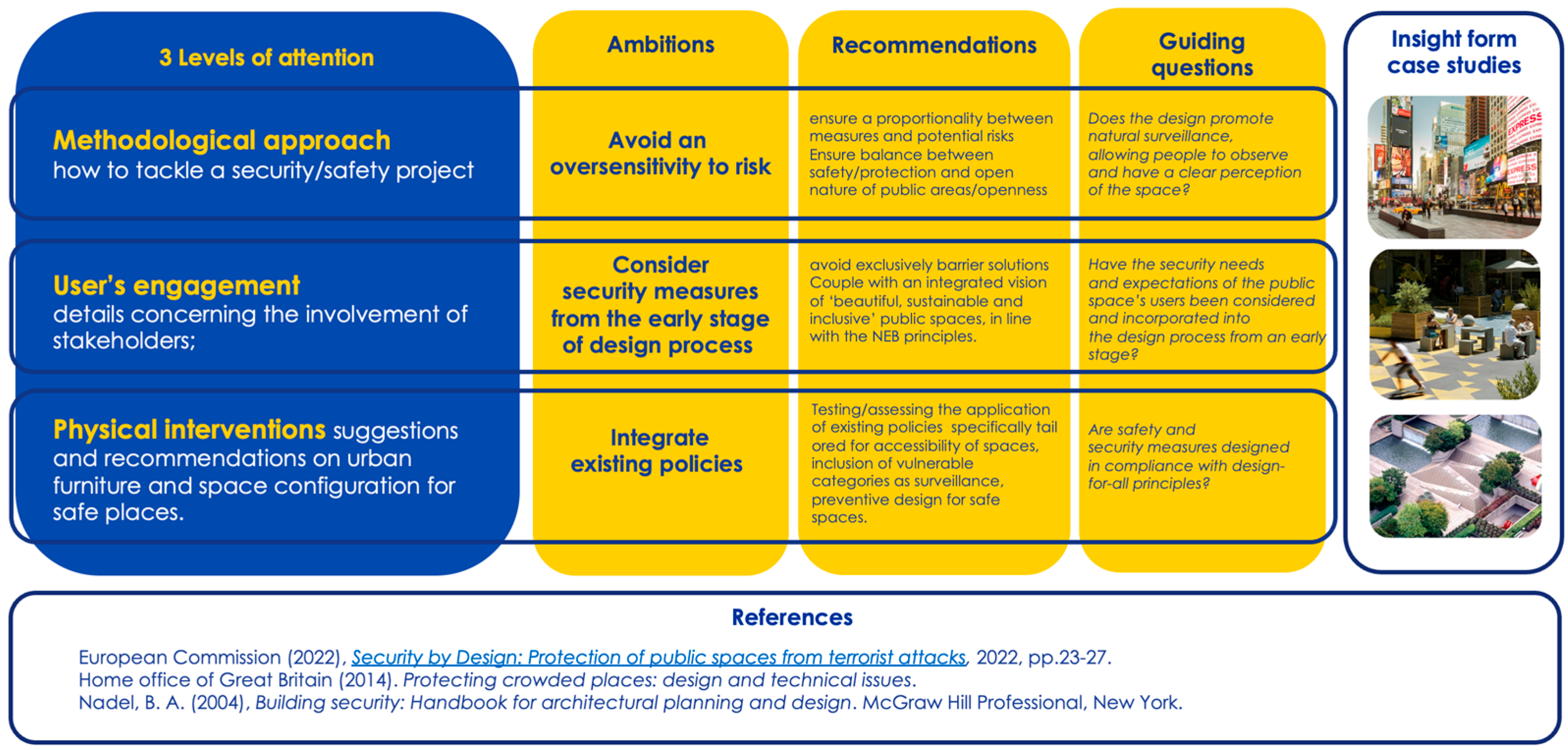

It is structured as a matrix that considers three main focus levels:

Methodological approach—how to address a security/safety project.

User involvement—details regarding stakeholder engagement.

Physical interventions—suggestions and recommendations on urban furniture and spatial configuration for safer places.

Each level of the methodology is structured into clusters of transversal ambitions and overarching goals aligned with varying levels of attention, primarily derived from EU priorities and policy recommendations. Where relevant, additional sources relating to the SBD approach were also incorporated to ensure a comprehensive foundation. These ambitions are further operationalised through recommendations, grounded in key policy documents, reports, and studies relevant to EU priorities and the SBD framework. To support the practical application of these recommendations, guiding questions are provided to clarify the intent behind each recommendation and qualify the attractiveness and relevance of a space. The Atlas concludes with insights from case studies corresponding to each level of attention and ambition. These curated examples—covering a broad spectrum of urban contexts across Europe and beyond—serve both as illustrative design scenarios and as the foundation for a portfolio of projects and initiatives from which practitioners can draw inspiration and lessons learned. The final layer of the tool features a set of references, including scientific literature, policy documents, regulations, and strategic frameworks, which informed the ambitions and recommendations. These references explicitly link to the wider European policy ecosystem on public space security and to the core values of the New European Bauhaus.

The Atlas canvas (

Figure 2) facilitates virtual experimentation with SBD approaches in pilot projects to foster innovation and adaptability. This allows testing and refining different solutions before physical implementation, reducing potential disruptions and optimising effectiveness. This resonates with the requirements of flexibility and anticipation that should increase the optimisation of uncertainty suggested by Foucault.

Another potential function of the Atlas is supporting the assessment of SBD strategies within various urban contexts, including permanent infrastructure, temporary installations, and public events. Its versatility makes it applicable across different scenarios, reinforcing its value as a decision-support tool.

Beyond its methodological framework, the Atlas also serves as a knowledge repository, offering insights from case studies to illustrate best practice in security-conscious urban design. Providing concrete examples enables practitioners to align their projects with proven strategies while fostering continuous learning and adaptation. In this scenario, the Atlas helps reconnect security assessments with Europe’s broader policy ecosystem governing public space security. It aligns with existing policies, regulations, and academic research, ensuring that security interventions are both evidence-based and contextually relevant, combining general aspects (such as avoiding risk hypersensitivity and assessing the value of places) with more operational actions (such as design elements or urban furniture layout) and hybrid solutions merging urban art with security regulations.

3.2.2. The SAFE CITIES Tools Testing

Following the approach mentioned above, the project has developed its SVA tools and Atlas by preliminarily testing them in four pilot sites: the stadium in Gdask (Poland); a shopping mall in Larnaca (Ciprus); the Paaspoop Festival in the Netherlands and the cross-border Transalpina square in Gorizia-Nova Gorica, the scene of many events of GO2025-European Capital of Borderless Culture.

In all of these pilot sites, a multi-level approach on security [

45] was developed through several steps: the project staff involved the authorities in charge of security organisation/planning and all the stakeholders in charge of collaborating in the maintenance of safety or possible intervention in case of emergency/terrorist attack. Starting with a discussion with these stakeholders, and in some cases with Local Citizen Network and end users, the case study then included the testing application of some versions of the tools.

In the specific pilot site of Gorizia and Nova Gorica, this workflow was demonstrated and discussed in a dedicated demo-event in March 2025. The pilot site was Piazza Transalpina; also known as Trg Europe or Europe Square, it is a unique public space that physically and symbolically unites the Italian city of Gorizia and the Slovenian city of Nova Gorica [

46]. This square stands as a powerful emblem of European unity, reconciliation, and cross-border cooperation: the border runs through the entire length of the square, marked, however, only by symbolic and visual elements. As the focal point for GO! 2025, it hosts cultural events that celebrate the shared heritage and future of the twin cities, offering visitors a tangible experience of European unity and cooperation. Planning security/safety measures and emergency protocol in this location has been a big challenge from the start, due to the influence of space on two different local and state regulatory set of mandatory protocols.

Indeed, the Gorizia-Nova Goriza pilot site was chosen as the location for the demo event (and related workshops) because, compared to the other areas involved, it allowed the project tools to be tested in a particularly complex context, having to respond to the needs of two different teams of national organisations (municipalities, police forces, first responders). The other pilot sites were used more as starting points presenting more straightforward conditions (including that of Cyprus, which, although located in a strongly border area, was in a national territory).

In this cross-border area a very large security team and stakeholder community is engaged: representatives of both municipal administrations, the two local police delegations, firefighters from both sides, the Italian Red Cross, and the Italian and Slovenian civil defence. With this transnational group, several preliminary activities where performed: the group shared with SAFE CITES staff the maps of the area (including specifics of buildings facing the square, existing street furniture, and other architectural features) alongside an initial survey of existing or planned security features for GO2025 events (cameras, barriers, officer controls, etc.).

The decision to focus in depth on the Gorizia-Nova Gorica cross-border pilot site stemmed from its unique characteristics as a symbolic and functional space that physically unites two cities across national borders, each governed by different legal and administrative frameworks. However, we recognise that focusing primarily on this single, highly specific site poses challenges for generalising the findings to other urban contexts.

The SVA application has been performed through the beta version of the tool “SERVE—SEcuRity Vulnerability assEssment”: the Transalpina Square was marked on the tool’s virtual map and participants were guided to customise the overall existing security assessments. In a second stage the group was invited to select from a predefined list of potential threats, as the system guided users through a structured evaluation process, using step-by-step risk assessments to determine the impact, attractiveness, and severity of each threat. The testing allowed both the assessment of the threat and a tailored specific risk relevant to the location. It has helped the stakeholders to imagine new or different security measures relevant to the location or threat.

The Transalpina cross-border square demo event also tested the SBS—The Tool for Protecting Large-Scale Public Events. The Scenario Builder & Serious Gaming Simulator (SBS) was developed to allow security teams to construct detailed 3D event venue models, clearly visualising security layouts and potential vulnerabilities. Starting from a realistic render of the square and of the GO2025 kick-off event, which included the actual placement of the stage, event entrances and other temporary equipment, teams have had the opportunity to simulate various security threats, including crowd surges, drone attacks, and unattended items, in a VR-enabled environment that enhances situational awareness and simulates crowd behaviour.

Beyond training, SBS enables teams to test security measures before an event begins, with authorities able to optimise resource deployment, refine emergency response plans, and identify weaknesses before they become critical issues. As a result, security personnel can anticipate potential threats and refine their strategies, ensuring a faster, more effective reaction in real-world emergencies.

During the Gorica-Nova Gorica event, both the SERVE and SBS tools underwent a testing phase and a participatory evaluation involving all the stakeholders. Participants were invited to use the tools and to actively assess their usability, clarity, and relevance for cross-border security planning. The cross-border pilot in Piazza Transalpina particularly highlighted both the opportunities and complexities of safeguarding transnational public spaces. The presence of overlapping jurisdictions and varied legal mandates necessitated a high degree of flexibility in both the assessment methodologies and the security planning processes. SERVE’s customisable risk assessment modules and SBS’s 3D scenario simulations offered stakeholders novel means to collaboratively assess vulnerabilities, experiential learning in a safe setting, preparing stakeholders for a wide range of possible threats, including emerging challenges such as drone incursions and chemical incidents.

The feedback collected during this phase praised the flexibility in adapting to different regulatory environments, such as those simultaneously at the Italian-Slovenian border. However, some participants recommended further customisation features to better address highly localised regulatory differences and operational practices.

Similarly, the SBS tool was positively received, with particular praise for its immersive 3D visualisation and simulation capabilities. Security teams reported that simulating complex scenarios such as simultaneous emergencies, crowd panic, and drone intrusions significantly enhanced their understanding of potential vulnerabilities and improved their readiness to respond. The VR-enabled environment was considered highly beneficial for decision-making training and for identifying weak points in event layouts that would not be immediately visible through traditional planning tools. Recommendations for improvement included the expansion of predefined threat libraries and the integration of real-time crowd density data feeds for even more accurate simulations.

Overall, the SAFE CITIES deployment addressed two critical challenges. First, by focusing on flexible, scenario-based vulnerability assessments and participatory simulation exercises, it promoted a more nuanced understanding of risks as they enabled stakeholders to tailor security interventions to specific threats without defaulting to generic, heavy-handed physical fortifications [

47]. This resonates with contemporary critiques of the over-application of CPTED principles [

47,

48], where surveillance and territoriality have sometimes been prioritised at the expense of public life.

Second, the deployment emphasised the importance of governance as a dynamic and participatory process. The project tested a portion of process by involving local authorities, civil society, and emergency services in the assessment and planning phases fostering a more balanced, flexible, anticipatory, risk-aware approach. It is not yet clear if this model is able to strengthen informal social control networks and supports self-regulation mechanisms [

10], however it allows to enlarge the participating arena on a sensitive topic.

Both SERVE and the SBS tools have the advantage that they can be applied in a dynamic way to single venues or events: no matter the size of the city, even a small town can use these tools to shape or fine-tune the design of security measures for a temporary event (such as a festival whose location has already been defined, a sporting event, etc.) or for recurring activities (such as markets, concerts) and even to check and refine security measures of usually crowded public spaces (a train station, a square, a church). Both tools are based on knowledge of a single space and do not need to be operated by a specific level of governance: information can be provided by an organiser or event planner or better it can result from a participatory process which engages relevant stakeholders as stated above. In this case the tools shaped by SAFE CITIES can have an impact not only on space but on a more general collective empowerment of those involved in security issues (even when they belong to different national organisations, as happened in the Gorizia-Nova Gorica demo).

Within this framework, implementing the Atlas methodology could provide additional empirical evidence. The Atlas methodology structures the workflow through sequential, participatory steps from spatial mapping to vulnerability assessment, scenario simulation, and the co-design of mitigation strategies. It provides a systematic way to ensure that the security needs of the public space are considered alongside, and not in opposition to, its civic and social dimensions. By requiring stakeholders to move iteratively between risk identification, threat evaluation, and mitigation co-design, Atlas operationalises a form of “secure governance” attentive to both the physical characteristics and the symbolic, relational dimensions of the urban space [

31].

By promoting a flexible and modular evaluation, and allowing local actors to calibrate security measures in proportion to assessed risks rather than imposing standardised, rigid solutions, the Atlas can support urban governance that avoids the pitfalls of over-securitisation. Moreover, including the Atlas in the process of security-by-design can enhance the value of procedural transparency and strengthen collective reflection. Stakeholders, through the guided workflow, are both able to reflect on operational vulnerabilities and on broader urban values such as inclusivity, accessibility, and democratic use of space. This dimension can contribute to achieving this balance by framing security as a dynamic negotiation between multiple urban functions, rather than a singular technical problem. This aspect would be critical in the case of urban spaces such as the cross-border context of Gorizia-Nova Gorica, where the harmonisation of distinct regulatory systems is a fragile balance and should not only provide operational measures but enabling the creation of a shared security culture without eroding the openness and permeability of the square at the same time.

Nevertheless, as with the tools themselves, some areas for refinement emerged. The Atlas is still a management tool, but it is not yet able to answer the need for greater adaptability to different scales and types of public spaces and for enhanced integration with real-time spatial and environmental data. Future iterations of the Atlas methodology focus on increasing its responsiveness to dynamic contexts, ensuring its relevance for temporary event planning and longer-term urban design processes.