1. Introduction

Urban development is increasingly focused on integrating smart technologies into planning processes. However, historic cities face unique challenges in balancing modernisation with the preservation of cultural heritage. The integration of technology in smart cities is vital for fostering economic progress, sustainability, and improving quality of life [

1]. It is equally crucial to consider socio-cultural factors to ensure inclusivity in urban development [

2,

3]. Furthermore, cultural heritage sites play a significant role in shaping urban identity, fostering community cohesion, and promoting economic and environmental sustainability [

4].

While smart technologies are increasingly employed to document and manage heritage assets [

5], these implementations remain largely project-specific and lack consistent empirical evaluation across contexts. Their overemphasis in smart city agendas can marginalise social dimensions such as participation, cultural value, and identity preservation. Technology-centric approaches often overlook the embedded cultural narratives and everyday social practices that give places meaning, particularly in heritage-rich contexts. Although digital literacy is associated with increased engagement in urban initiatives [

6], several studies challenge the assumption that higher digital competence necessarily translates to civic participation [

7]. This tension highlights the need to interrogate the role of technological equity in shaping just and culturally inclusive smart cities.

There is growing recognition that cultural heritage is not simply a static set of preserved artefacts but an evolving element of place identity and community life. Smart city frameworks that integrate heritage have the potential to support place making practices that build social resilience, encourage local ownership, and reinforce shared memory [

8]. Various studies illustrate how digital platforms aid in cultural dissemination [

9], engage communities in historic contexts [

10], and develop smart heritage tools for adaptive reuse [

11]. However, these contributions remain fragmented and rarely offer a unified framework linking heritage, technology, and spatial practice.

Despite the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and digital tools in smart city management, their potential for fostering cultural belonging, local pride, and inclusive governance is still underexplored [

12]. AI is typically framed through functionalist perspectives—such as data analytics, automation, and infrastructure efficiency—yet its application in reinforcing cultural memory, civic identity, and site-based place making remains under-theorised. Technologies like augmented reality (AR), digital twins, or community-based storytelling platforms can support deeper citizen interaction with urban heritage, but their integration into planning remains sporadic and under-conceptualised.

The recent literature on urban digitalisation and smart city development highlights the increasing role of technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), augmented reality (AR), digital trade platforms, and Internet of Things (IoT) systems in promoting urban efficiency, carbon reduction, and sustainable innovation. Studies from Chinese cities, for example, demonstrate how digitisation improves green total factor energy efficiency [

13], how smart city policies yield spatial spillover effects on carbon reduction [

14], and how digital trade infrastructure can unlock sustainability gains [

15]. These insights are highly relevant for urban heritage contexts, as they show how large-scale digital systems can be adapted to site-specific challenges. However, while these technologies show promising potential, the current literature still lacks detailed analysis on how specific technologies are selected, phased, or evaluated for cultural heritage protection—including cost–benefit considerations and governance frameworks. This study identifies these implementation dynamics as critical areas for future research, especially when applying smart solutions in heritage-rich environments that require cultural sensitivity, community input, and technical adaptability.

A significant gap persists in current scholarship: while various disciplines recognise the relevance of heritage, place making, and digital transformation, no study to date has proposed an integrated conceptual framework that binds these domains into a cohesive model of smart city development. Previous works address these elements either individually or in loosely connected terms and rarely explain how their integration can function in practice through concrete planning mechanisms or digital strategies. They lack a synthesis that clarifies how cultural heritage sites can contribute to participatory governance, urban identity, and digital inclusivity.

This research seeks to address this gap by asking two guiding questions:

How can cultural heritage be systematically integrated with smart city strategies through place making to support coordinated urban development?

What digital tools, governance mechanisms, and spatial planning practices enable the protection and revitalisation of cultural heritage within smart city frameworks?

The study engages with three major theoretical traditions to ground its conceptual model: smart urbanism, which explores the governance and infrastructure logics of digital cities; critical heritage studies, which interrogate power, authenticity, and community memory in cultural policy; and place identity theory, particularly the triadic model proposed by Matlovičová [

16], which distinguishes between place identity, place image, and place reputation. These perspectives offer essential insights into how technology mediates the perception and experience of urban heritage and how local narratives can be preserved or reinterpreted in digital environments. However, each of these traditions has theoretical limitations. Smart city theory often prioritises efficiency, surveillance, and infrastructure over cultural and humanistic concerns [

17]. It frequently neglects the role of historical identity and socio-cultural memory in shaping the urban experience. Likewise, dominant approaches in cultural heritage protection have traditionally focused on conservation and authenticity, often overlooking opportunities for creative adaptation, participatory governance, or digital integration [

18]. Theories of local development, although attentive to community needs and spatial justice, tend to lack engagement with emerging technologies and their socio-spatial implications.

This paper addresses these theoretical blind spots by offering a framework that explicitly bridges digital infrastructure with cultural meaning. It recognises heritage as an evolving and participatory process rather than a static object of preservation. By embedding digital tools in culturally grounded planning practices, the model proposes a more integrative and responsive approach to smart urban development. Furthermore, the framework is enriched by interdisciplinary perspectives from sociology and anthropology. Concepts such as collective identity, spatial belonging, ritual practice, and cultural resilience provide additional analytical depth. These lenses help to uncover the subtle ways in which communities interact with heritage sites, resist or embrace technological interventions, and co-produce the meaning of place. This theoretical plurality ensures that the proposed model is not only functionally useful but also contextually and culturally sensitive.

Methodologically, the study conducts a systematic literature review (SLR) combined with qualitative content analysis. A total of 42 peer-reviewed articles were analysed, sourced from databases including Web of Science and Scopus, using screening platforms such as Covidence and coded through MAXQDA. The process followed PRISMA guidelines and employed open, axial, and selective coding in line with Corbin and Strauss [

19]. The study identifies key themes, emerging patterns, and conceptual clusters across four interdisciplinary domains: urban planning, smart governance, heritage conservation, and digital place making. The framework assumes that cultural heritage-driven place making, when paired with inclusive digital infrastructure, contributes to stronger civic identity and participatory smart governance.

The result is a conceptual framework that maps the interrelations between heritage, place-based identity, participatory digital platforms, and urban innovation. This model aims to guide policymakers, planners, and researchers in designing culturally inclusive smart city systems that prioritise community engagement, site-specific strategies, and technological equity.

Finally, while this research offers a theoretical contribution to a highly fragmented field, it recognises inherent limitations. These include the lack of empirical case studies, potential generalisation risks due to contextual diversity, and the reliance on secondary data sources. As such, the framework is presented as a flexible tool to be adapted and refined in future empirical work across culturally and technologically diverse urban environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Approach

This study adopts a comprehensive and multi-stage research methodology, combining a systematic literature review with an in-depth qualitative content analysis to investigate the interplay between cultural heritage, smart city development, and place making. The approach is rooted in best practices for systematic inquiry and aims to ensure methodological transparency, reproducibility, and analytical richness. Drawing on established guidance for systematic reviews [

20], and grounded theory coding techniques [

19], this methodology is carefully structured to generate a conceptual framework through rigorous data collection, analysis, and thematic synthesis.

2.2. Systematic Literature Review

Systematic reviews are valuable tools for identifying and synthesising existing bodies of knowledge across disciplines. They allow researchers to uncover thematic patterns, expose gaps, and clarify conceptual developments. In this study, the systematic review process involved repeatable and structured search protocols, dual-layer screening, and transparent documentation. Qualitative content analysis further enhanced this foundation by transforming unstructured data into conceptual codes and categories. As Shava et al. [

21] argue, qualitative analysis is both creative and interpretive, requiring methodical breakdowns of raw data to extract meaning and support theory construction.

2.3. Search Strategy

The research began with a carefully designed search strategy targeting two complementary databases: Web of Science and Google Scholar. Web of Science was chosen for its academic rigour and curated indexing of peer-reviewed publications, while Google Scholar expanded the coverage to include grey literature and emerging interdisciplinary work. This balanced approach enabled a comprehensive review of scholarly contributions across multiple fields, including urban studies, cultural heritage management, digital governance, and urban planning.

Search terms were identified based on the core research themes and structured into complex Boolean strings to ensure thoroughness. Key terms included combinations of “cultural heritage”, “smart city”, “urban development”, “place making”, “community engagement” and “digitalisation”. Search results were limited to English-language publications from January 2010 to January 2024 to capture both foundational and recent developments in the field.

2.4. Article Selection Process

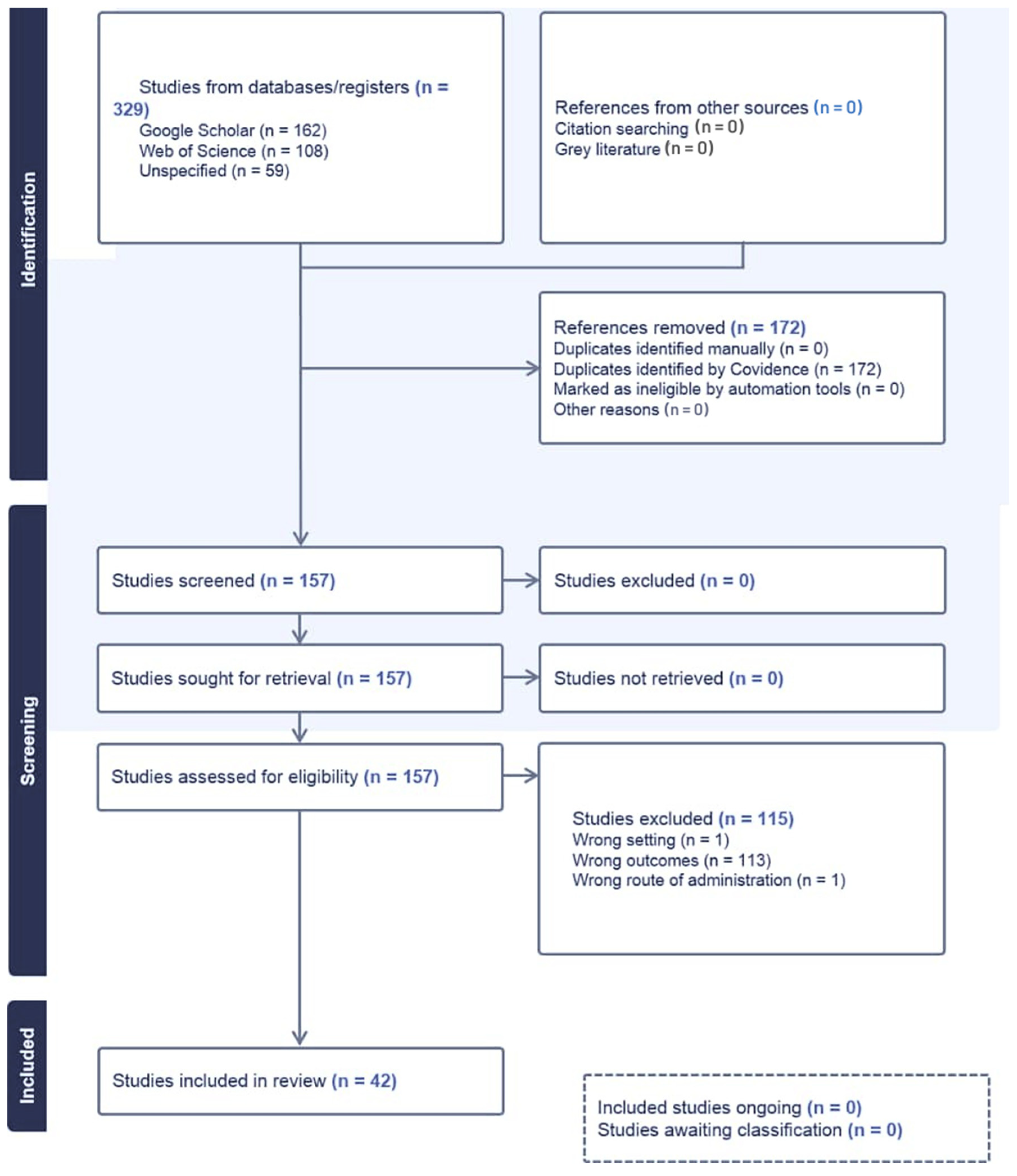

The initial search results yielded 329 articles. These were imported into EndNote 21, which was used for preliminary organisation and automatic duplicate detection. EndNote’s citation tracking and categorisation tools facilitated sorting, but critical review decisions were conducted manually by the research team to maintain interpretive consistency. Duplicate entries and irrelevant records were removed, reducing the dataset to 157 unique articles for screening.

To manage the screening process, the remaining records were transferred to Covidence.org, an online platform for systematic literature reviews. Each article was screened and analysed by the researcher using a systematic protocol. A summary of the inclusion and exclusion criteria applied at both the abstract and full-text stages is provided in

Table 1 to enhance methodological transparency. Predefined criteria were applied consistently, and interpretive decisions were documented through reflective coding memos. The use of consistency checks across coding phases further supported internal coherence throughout the study. The sequential research steps followed in this study are summarised in

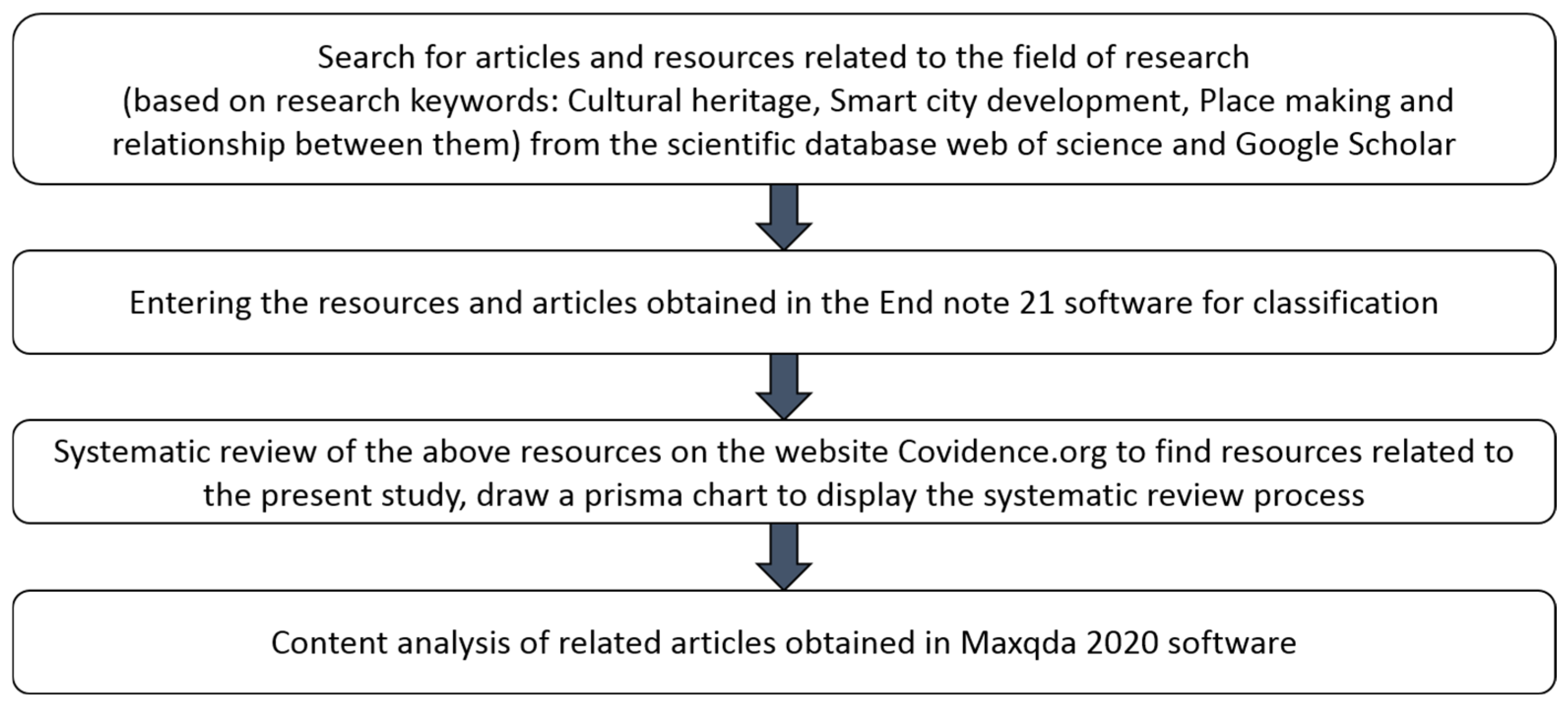

Figure 1. Ultimately, 42 articles met all criteria for inclusion in the qualitative synthesis.

While Covidence supported structured screening, the final inclusion decisions were based on a detailed evaluation of each article’s methodological transparency and thematic relevance. Studies were excluded if they addressed smart city technologies without any cultural or participatory framing, or if they focused solely on heritage tourism without broader urban planning implications. Common exclusion patterns included overly technical ICT studies with no social dimension, or heritage analyses unrelated to digital or spatial planning frameworks.

Although the primary screening and coding were conducted by the lead researcher, consistency checks were applied through reflective memos and periodic peer debriefing with co-authors to ensure interpretive alignment. Given the qualitative nature of the synthesis, a formal inter-rater reliability score was not calculated, but a cross-validation of themes was performed during the axial and selective coding phases.

The article selection process is documented through a PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 2). This diagram outlines each phase of selection from initial identification to final inclusion. Articles were excluded primarily due to lack of relevance to the research questions, insufficient methodological detail, duplication, or failure to address the intersection of cultural heritage, smart cities, and place making. These exclusion reasons are also summarised in

Table 1 and reflected in the PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 2).

2.5. Qualitative Content Analysis Using MAXQDA

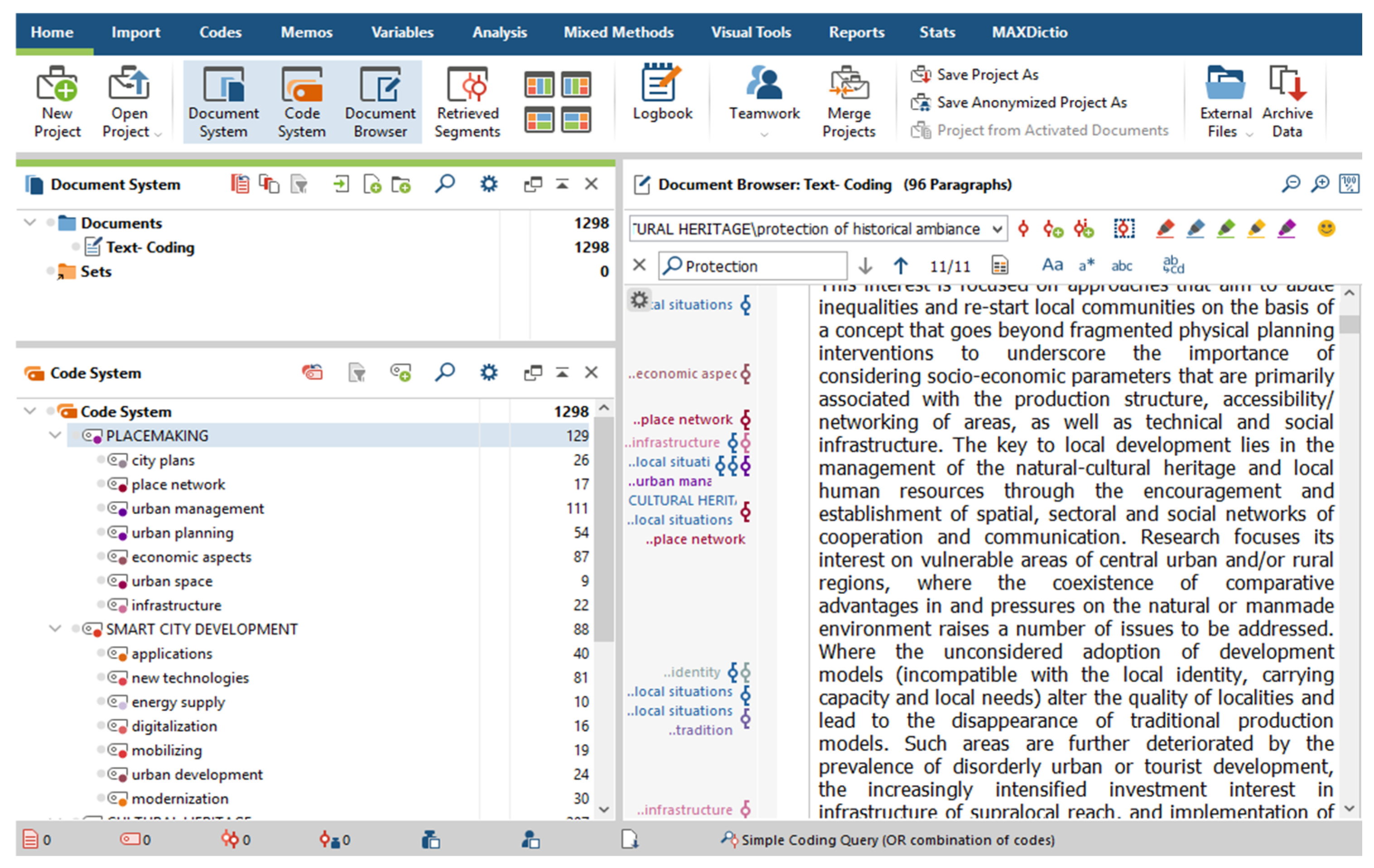

Following selection, qualitative data analysis was conducted using MAXQDA 2020, a software environment for systematic text coding and thematic analysis. The analysis followed a three-phase coding process:

Open Coding: During this phase, articles were read line by line and annotated with descriptive codes. A total of 1280 subcodes emerged, reflecting a wide spectrum of concepts such as digital infrastructure, heritage preservation, policy integration, participatory urbanism, and socio-spatial identity. Each subcode captured nuanced references to the central research themes across various geographic and disciplinary contexts.

Axial Coding: In this phase, related subcodes were grouped into higher-level categories based on their conceptual relationships. This process led to the formation of 27 core categories, including themes like “urban regeneration”, “local cultural identity”, “technological mediation”, and “community-driven planning”. The axial phase helped establish connections between the various dimensions of the literature and facilitated cross-comparison between studies.

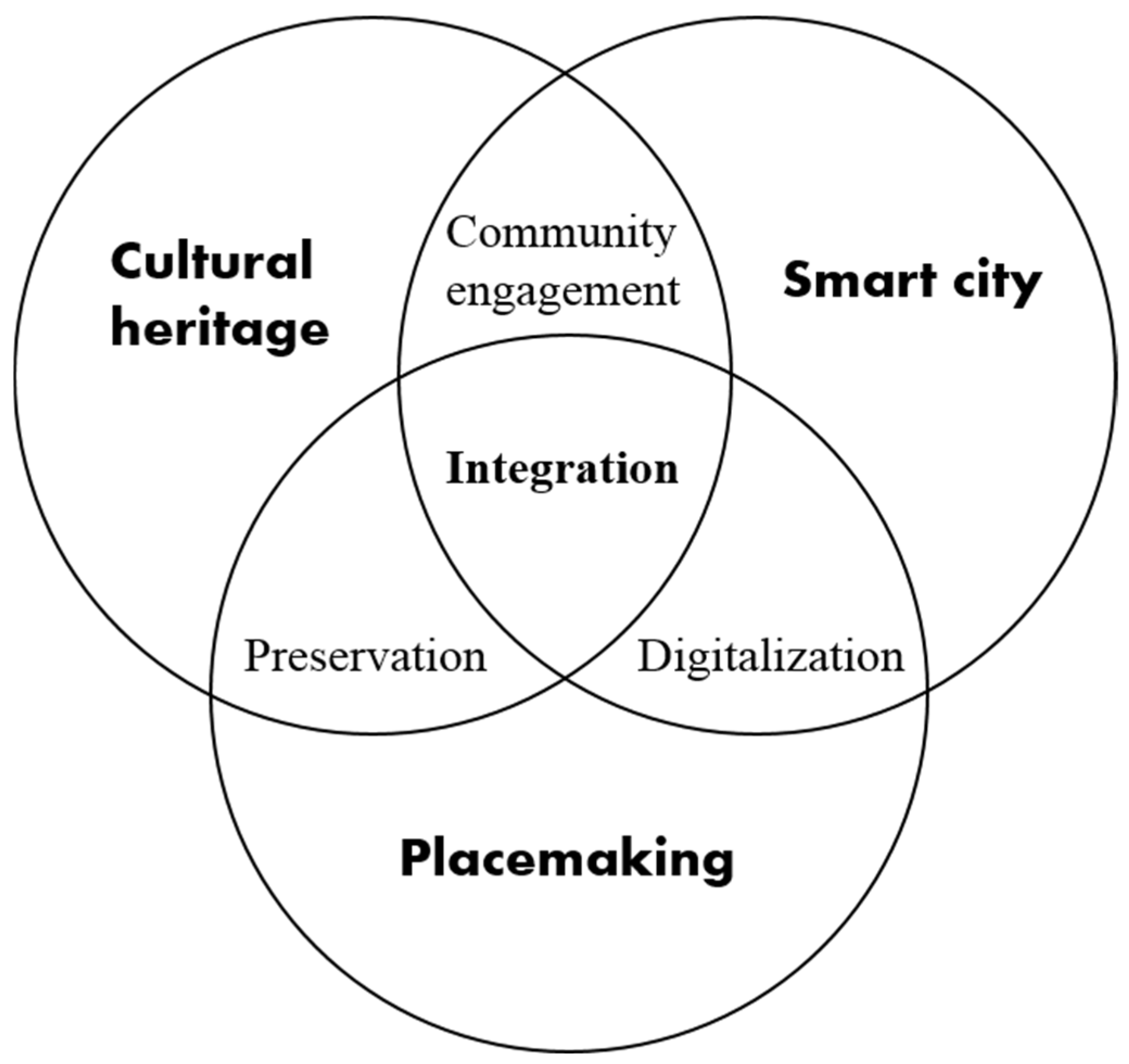

Selective Coding: Finally, selective coding was used to integrate the axial categories into a conceptual framework. Four major dimensions were identified: preservation, digitalisation, community engagement, and integration. These components emerged as central to understanding how cultural heritage interacts with smart urban initiatives. Their emergence was not arbitrary but was the result of recurrent appearance, theoretical salience, and conceptual saturation across the data.

Due to the complexity of the full coding hierarchy (comprising 1280 codes),

Figure 3 presents a representative portion that visualises the coding logic used during thematic analysis.

2.6. Comparative and Cross-Contextual Analysis

While this study’s core approach is qualitative, comparative elements were also integrated. Articles from different geographic and cultural settings were analysed comparatively to identify cross-contextual patterns. MAXQDA’s matrix functions and code co-occurrence tools were employed to track these comparative insights systematically, ensuring consistency across diverse case studies.

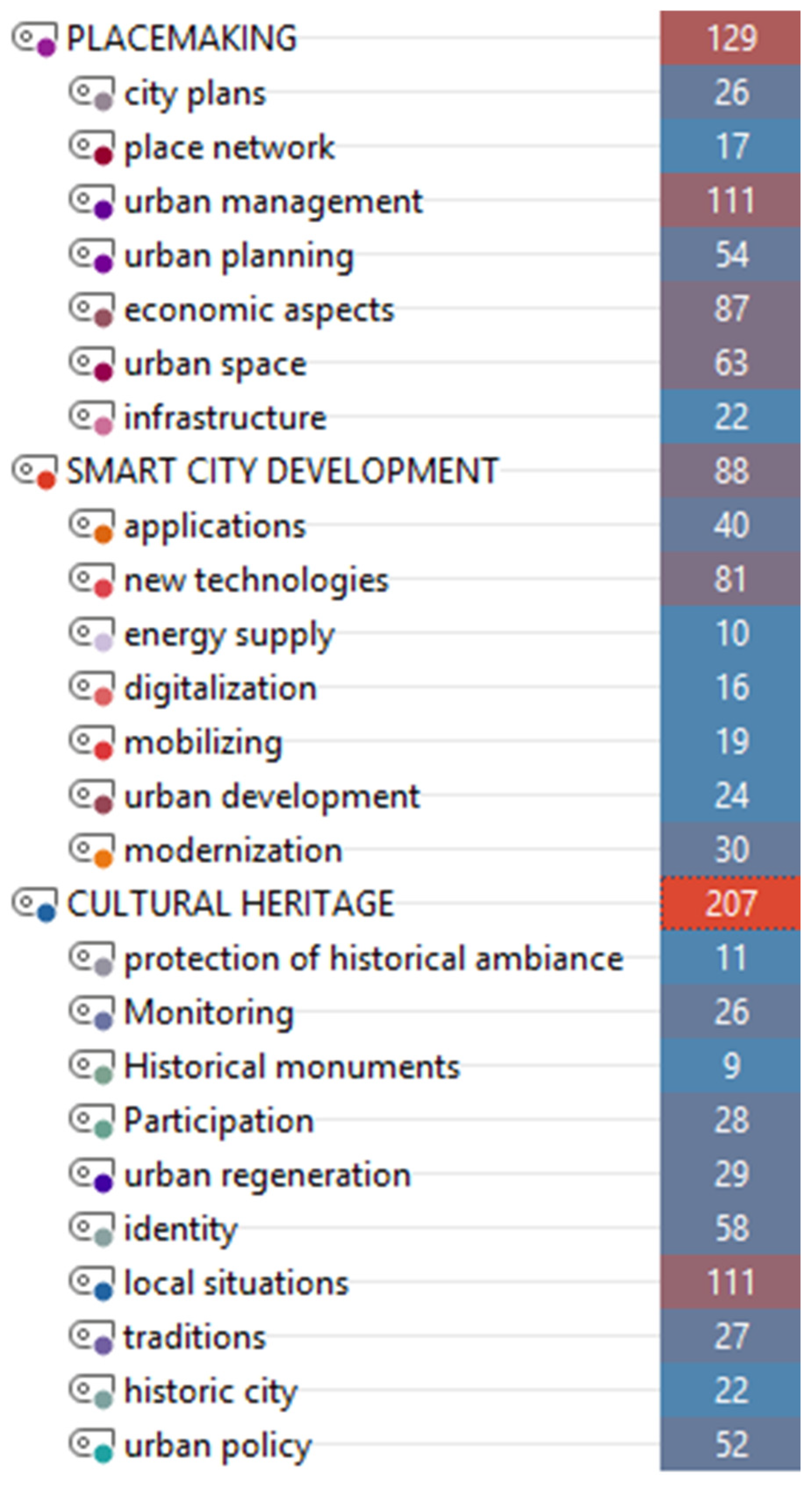

It is important to note that frequency data were recorded to assist with identifying recurring themes but were not used as indicators of importance. Instead, emphasis was placed on conceptual relevance, depth of discussion, and thematic interconnectedness.

Figure 4 clearly shows the importance of each subcode category by the number of repetitions of each code. Themes such as “identity”, “local situations”, and “urban management” appeared most frequently, indicating a strong scholarly focus on place-specific socio-cultural concerns. This pattern supports the analytical depth captured during coding and reflects how certain themes played a central role in shaping the conceptual model.

The interpretive significance of a theme was based on its contextual role within the literature, not merely on repetition. This study does not include bibliometric or citation mapping techniques, which are commonly used in systematic reviews. However, such methods (e.g., co-citation or keyword network analysis) could be valuable in future research to complement the qualitative synthesis presented here.

In conclusion, the methodological approach presented here ensures a transparent, reproducible, and theoretically grounded pathway from literature review to conceptual framework. Through meticulous source selection, systematic screening, multi-layered coding, and critical interpretation, this research contributes to the growing discourse on how cultural heritage can be embedded meaningfully within smart city agendas and participatory urban planning strategies.

3. Results

The conceptualisation of literature and research findings is the most important part of the present study. The presentation of this conceptual framework is in the form of developing a model for place making with a smart city approach in cities of historical value and cultural heritage. That is, the most important elements and characteristics of communication between each of the concepts of cultural heritage, smart city, and place making which are interconnected—are identified, interpreted, and explained. While the study remains literature-based, the coding structure provides an analytical foundation that can support future empirical applications in real-world planning scenarios.

3.1. Results from Open Coding

The initial stage of analysis produced 1280 open codes that reflect a wide range of recurring themes across the literature. In the domain of cultural heritage, prominent concepts included environmental conditions, cultural identity, historical preservation, and community participation. Smart city-related codes frequently referenced technology integration, software infrastructure, and digital service development. For place making, common themes included urban space design, infrastructure planning, economic revitalisation, and spatial connectivity.

Rather than treating frequency as a proxy for importance, codes were evaluated based on their conceptual relevance and thematic depth. For instance, the code “identity” appeared across multiple disciplines, but its significance was tied to its centrality in sustaining cultural continuity and fostering shared meaning in urban life. This qualitative richness informed the transition to more abstract categories in the next stage of analysis.

3.2. Results from Axial Coding

Through interpretive synthesis, the open codes were clustered into 27 higher-order categories across the three core domains. In cultural heritage, dominant themes included local identity, urban regeneration, participatory governance, and the protection of historical assets. Smart city-related categories featured digital modernisation, software integration, infrastructure readiness, and energy systems. Place making themes highlighted spatial organisation, urban management, economic development, and planning mechanisms.

Importantly, several categories spanned multiple domains. For example, “participation” emerged both in cultural heritage and smart city contexts, highlighting its dual role in sustaining identity and enabling inclusive digital governance. These conceptual intersections strengthened the analytical structure and allowed for a more holistic reading of how these domains interact in theory and practice.

The relationships identified during axial coding are visually summarised in

Figure 5, which maps the key themes across the three primary domains—cultural heritage, smart city development, and place making. This figure reflects the conceptual intersections revealed during coding and lays the foundation for the synthesis presented in the final framework.

3.3. Results from Selective Coding

Building on the axial coding phase, selective coding aimed to distil the most conceptually significant and thematically interconnected elements into higher-order categories. This process led to the formation of four overarching conceptual components: Preservation, Digitalisation, Community Engagement, and Integration. These components were not predefined but inductively developed through interpretive synthesis of the coded literature.

Preservation emerged primarily from axial codes clustered around cultural heritage themes such as identity, historical monuments, traditions, local memory, and environmental continuity. These concepts were frequently linked in the literature through discussions of cultural resilience, spatial rootedness, and the safeguarding of tangible and intangible assets. Together, they formed a coherent dimension focused on protecting heritage in urban development contexts.

Digitalisation was shaped by axial codes derived from the smart city domain, including digital infrastructure, software systems, technological innovation, energy management, and data governance. These themes collectively reflected the tools and strategies used to modernise urban functions and support efficient service delivery and were frequently associated with spatial planning and operational enhancement.

Community Engagement emerged from intersecting codes across both heritage and smart city literature that dealt with participation, inclusion, public trust, co-creation, and digital equity. These elements reflected the need for involving local communities in planning processes and ensuring that smart technologies do not marginalise but instead empower citizens. Codes related to civic interaction and democratic access to digital tools reinforced this category.

Integration was derived from codes and themes that spanned all three domains—heritage, technology, and place making. These included multi-stakeholder governance, adaptive reuse, policy alignment, and cross-sector planning. The literature often referenced the need for holistic urban approaches that bring together cultural identity, infrastructure modernisation, and citizen participation into a single, coordinated strategy. Thus, this component captures the synthesis and balance necessary for culturally sensitive smart city development.

Figure 6 visualises the conceptual framework that emerged from this selective coding phase. It highlights the interrelationship between the four components and demonstrates how they collectively support a model for integrating cultural heritage into smart city planning through inclusive, digitally enabled, and context-sensitive strategies.

Rather than being asserted as an abstract taxonomy, these four components reflect the layered conceptual structure identified through the literature coding process. Their emergence is grounded in patterns of thematic convergence and theoretical salience, demonstrating how diverse but interconnected urban discourses can be systematically integrated into a usable analytical framework.

4. Discussion

The key aim of this research was to formulate a conceptual framework that integrates cultural heritage with place making and smart city concepts. The framework is designed as a set of guiding principles for enabling transformation while ensuring that historic cities evolve intelligently without compromising their cultural and historical significance. This was achieved through a qualitative content analysis of systematically reviewed literature, allowing the extraction of key patterns and categories from diverse academic contributions. The three core concepts cultural heritage, smart cities, and place making are treated as dynamic and intersecting components essential to addressing the complex challenge of preserving identity while fostering innovation in urban environments.

While the resulting framework synthesises recurring themes from a multidisciplinary body of literature, its novelty lies in how it interprets these intersections as complementary rather than conflicting. Previous research has emphasised the challenges in reconciling heritage preservation with the push for digital modernisation [

3,

22]. Our findings align with these concerns but go further by proposing a framework where technology becomes an enabler of cultural identity, not merely a force of transformation. In this way, the framework addresses contradictions in the literature [

23], particularly those that treat smart cities and historical identity as mutually exclusive.

The first research question focused on identifying the critical parameters that define the interaction between place making practices and smart city development in heritage-rich urban contexts. Our analysis highlighted the role of urban governance, institutional capacity, and spatial planning strategies as foundational pillars for sustainable development in such cities. These factors are not only infrastructural or operational in nature but deeply tied to socio-political conditions that influence how smart interventions are adopted or resisted.

The second research question explored how the integration of smart technologies affects cultural heritage. Our results identified three interrelated dimensions: the retention and valorisation of heritage, active community participation, and the digital augmentation of place identity. Importantly, these findings suggest that smart technologies do not inherently conflict with heritage values but must be applied with cultural sensitivity and public engagement to produce meaningful outcomes. This moves beyond purely technological narratives to reflect a more socio-spatial and participatory interpretation of smart urbanism.

In positioning this framework within the broader field, it is necessary to critically compare it with other conceptual models. Unlike some earlier frameworks that either focus solely on digital infrastructure or on heritage tourism, this model emphasises integration across scales: symbolic, operational, and experiential. This comparative advantage situates our framework closer to hybrid models of urban development that recognise cultural memory and local specificity as assets in future-oriented planning. However, further comparative studies with other models from urban studies, heritage conservation, or adaptive reuse planning could help to strengthen this alignment.

The practical relevance of the framework also merits emphasis. Although the model is conceptual and developed from secondary literature, it offers utility for urban planning particularly in contexts where historical preservation and digital innovation must coexist. For instance, planners working in mid-sized heritage cities undergoing digital transitions may apply this framework to balance innovation and preservation by focusing on actionable elements such as digital equity, participatory planning, and adaptive infrastructure design. To ensure meaningful participation, strategies such as co-creation workshops, participatory design, and digital engagement platforms are essential. Addressing the digital divide through skills training, accessible technology, and policy support further enables inclusive community involvement in smart heritage planning.

To further ground this practical relevance, the study draws on two real-world urban cases—Dunedin (New Zealand) and Strijp-S (Netherlands)—to illustrate the framework’s applicability in diverse contexts. In Dunedin, heritage precincts have been revitalised through smart urban furniture, high-speed connectivity, interactive heritage trails, and co-created planning strategies such as the “Share an Idea” campaign. These initiatives align closely with the framework’s components of digitalisation, community engagement, and preservation [

24]. Strijp-S, a former industrial site in Eindhoven, demonstrates how adaptive reuse of historical structures can be coupled with participatory urbanism and digital innovation. Projects such as the “Plug-in-City” initiative and the use of augmented reality and smart infrastructure reflect the integrative potential of preservation, digitalisation, and inclusive engagement [

25,

26,

27]. The contrasting socio-cultural contexts of Dunedin and Strijp-S also illustrate how implementation priorities, community engagement strategies, and heritage values vary across cultures supporting the framework’s adaptability and cross-cultural relevance [

27]. In Dunedin, strong community involvement and the recognition of Māori cultural values shape digital heritage initiatives through inclusive governance and trust-building. In contrast, Strijp-S focuses on industrial heritage and innovation-led reuse, driven by creative industries. These differences show that smart heritage strategies must be tailored to local cultural norms and governance models, reinforcing the need for the context-sensitive adaptation of the framework [

28].

We acknowledge that the current reliance on literature-based coding limits probabilistic generalisation. However, the framework is intended to serve as a flexible, theory-informed tool that can be adapted and refined through future research. Subsequent studies may involve simulation-based scenarios, urban design workshops, or qualitative interviews with planners and community stakeholders to test the framework’s feasibility, contextual relevance, and operational impact.

Crucially, the practical application of this framework depends on the specific cultural, economic, and technological contexts in which it is used. Urban areas differ widely in their governance models, digital infrastructure, resource capacity, and community priorities. As such, this framework is not a prescriptive template, but rather a flexible tool that must be calibrated to local conditions. Practitioners and researchers are encouraged to adapt its components such as participation mechanisms or digital integration strategies—based on the readiness, needs, and socio-political dynamics of each city. This context-aware approach ensures that the model supports place-sensitive and culturally grounded planning outcomes.

Beyond its contributions, the framework is not without limitations. First, it is based solely on secondary sources and qualitative interpretation; no empirical data or case studies were used to test the operability of the framework in a live planning context. While the coding process was systematic and informed by grounded theory principles, it remains subject to interpretive bias. The use of a single researcher for the coding process further limits inter-coder reliability, and the selection of sources, though broad, may have excluded relevant grey literature or non-English academic work. In addition, the study does not incorporate bibliometric or quantitative methods such as citation network analysis, which could have helped identify overarching patterns and thematic clusters across the literature. Future research could benefit from a mixed-methods approach, combining qualitative analysis with quantitative tools, such as surveys or statistical indicators, to assess public acceptance of smart technologies in heritage contexts and further validate the framework’s applicability. These limitations must be acknowledged in any attempt to apply or extend the model.

The results also point to potential implementation barriers that deserve further exploration in both research and policy. These include not only resistance from preservationist communities and lack of digital literacy, but also financing constraints, limited institutional capacity, and challenges related to public acceptance of new technologies. In some contexts, “smart” systems may be perceived as invasive or misaligned with local cultural values. Addressing these barriers requires a combination of inclusive governance, transparent communication, and targeted investment in digital education. Mitigation strategies such as stakeholder engagement processes, heritage-based innovation incentives, and adaptive policy design should be explored to increase both feasibility and acceptance. A future research agenda should therefore include mixed-methods approaches—such as in-depth case studies, participatory mapping, or policy simulations—to empirically test and refine the proposed model.

Despite its limitations, the developed framework offers an actionable and integrative approach to managing urban transformation in historically significant contexts. It contributes to the emerging discourse on culturally aware smart cities by offering not only theoretical clarity but also a flexible guide for policy and planning. To enhance its practical value, future research should focus on translating this framework into an operational action plan supported by measurable indicators. These could include metrics such as levels of community participation, the accessibility of heritage sites, the degree of digital integration, and public satisfaction. Practical steps for implementation—such as stakeholder engagement protocols, inclusive technology rollouts, and adaptive policy mechanisms—will also be essential to support effective application across diverse urban contexts. By doing so, they would support urban practitioners and decision-makers in envisioning development strategies that are both technologically advanced and culturally rooted—preserving not just buildings or monuments, but the living narratives of place.

5. Conclusions

The importance of creative processes in urban design, in managing spaces for habitation, and in preserving identity and heritage within cities is increasingly evident. Particularly in historical urban contexts, place making serves as a core strategy for sustaining and enhancing a town’s cultural and spatial resources. This systematic review highlights that cultural and economic policies, urban planning and governance, infrastructure development, and communication networks are among the strongest drivers of sustainable cultural development in cities.

A notable gap in the literature concerns the role of smart city initiatives and their impact on cultural heritage resources, especially regarding the preservation and revitalisation of historic urban environments. While the integration of digital technologies into heritage contexts may appear to conflict with conservation principles, the findings suggest that, if implemented with care, such technologies can support accessibility, engagement, and interaction with historical areas—without undermining their distinct cultural identity. However, practical implementation requires place-sensitive planning, community participation, and alignment between digital tools and local policy instruments.

To support this, the proposed conceptual framework can be applied by urban planners and policymakers in various ways: for example, using it as a guideline when designing heritage-led urban regeneration projects, integrating it into participatory planning toolkits, or adapting it as an evaluative framework for cultural impact assessment in smart infrastructure developments.

Achieving this balance requires community engagement, inclusive planning, and a clear understanding of local values. Smart city transformation should not be seen as a purely technical endeavour, but as an opportunity to enhance cultural meaning and civic identity. This perspective helps connect analytical findings to broader theoretical implications: heritage is not a static element to be preserved in isolation, but a dynamic part of urban evolution that can guide and enrich technological innovation. In doing so, this study contributes to emerging interdisciplinary dialogues that treat urban heritage as both a cultural asset and a driver of social resilience.

Practically, the research underscores the need for policy and planning frameworks that align smart city strategies with cultural sustainability. This includes developing heritage-sensitive indicators, fostering cross-sector collaboration, and promoting digital tools that are inclusive, interpretive, and respectful of local narratives. The findings further suggest that many ancient cities have suffered identity loss due to rapid urban expansion and weak heritage integration. Accordingly, digital transformation must proceed with an acute awareness of place, people, and history.

Future research could apply this conceptual framework to real-world urban projects, compare case studies across diverse cultural settings, and examine how funding mechanisms, policy tools, and emerging technologies can better support creative heritage integration. Ultimately, this study demonstrates that the proposed framework is not only theoretically grounded but also practically adaptable across diverse urban contexts. Its strength lies in bridging digital innovation with cultural sensitivity—offering a scalable, transferable model for cities seeking to modernise without erasing their identity. By embedding community values into smart urban strategies, the framework redefines innovation as a culturally grounded, participatory process.