The Impact of Supervised Physical Activity in Urban Green Spaces on Mental Well-Being Among Middle-Aged Adults: A Quasi-Experimental Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. The “Moving Parks” Project

- Aged 45 to 65 years old;

- Able to write and read in Italian.

2.2. The Questionnaire

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

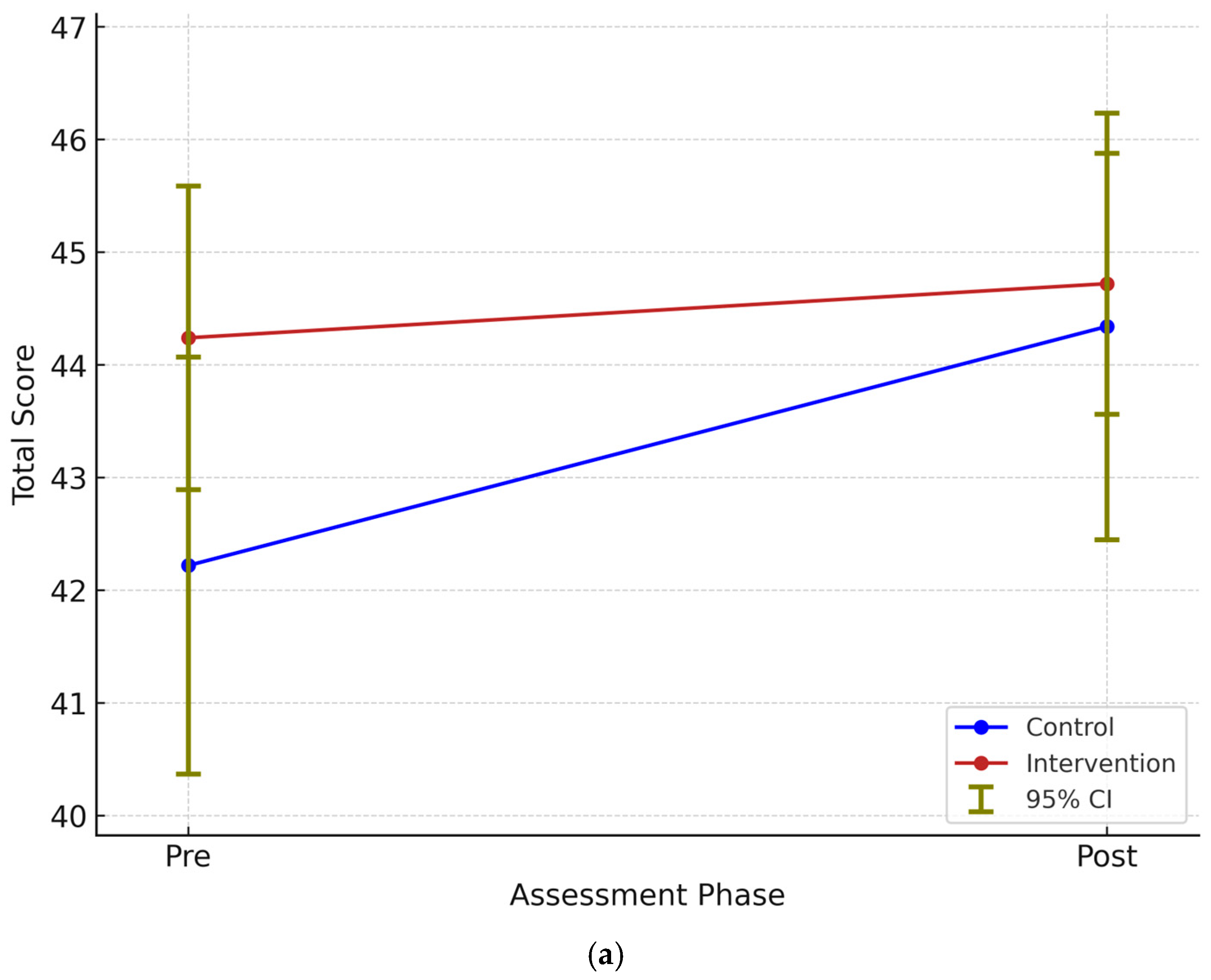

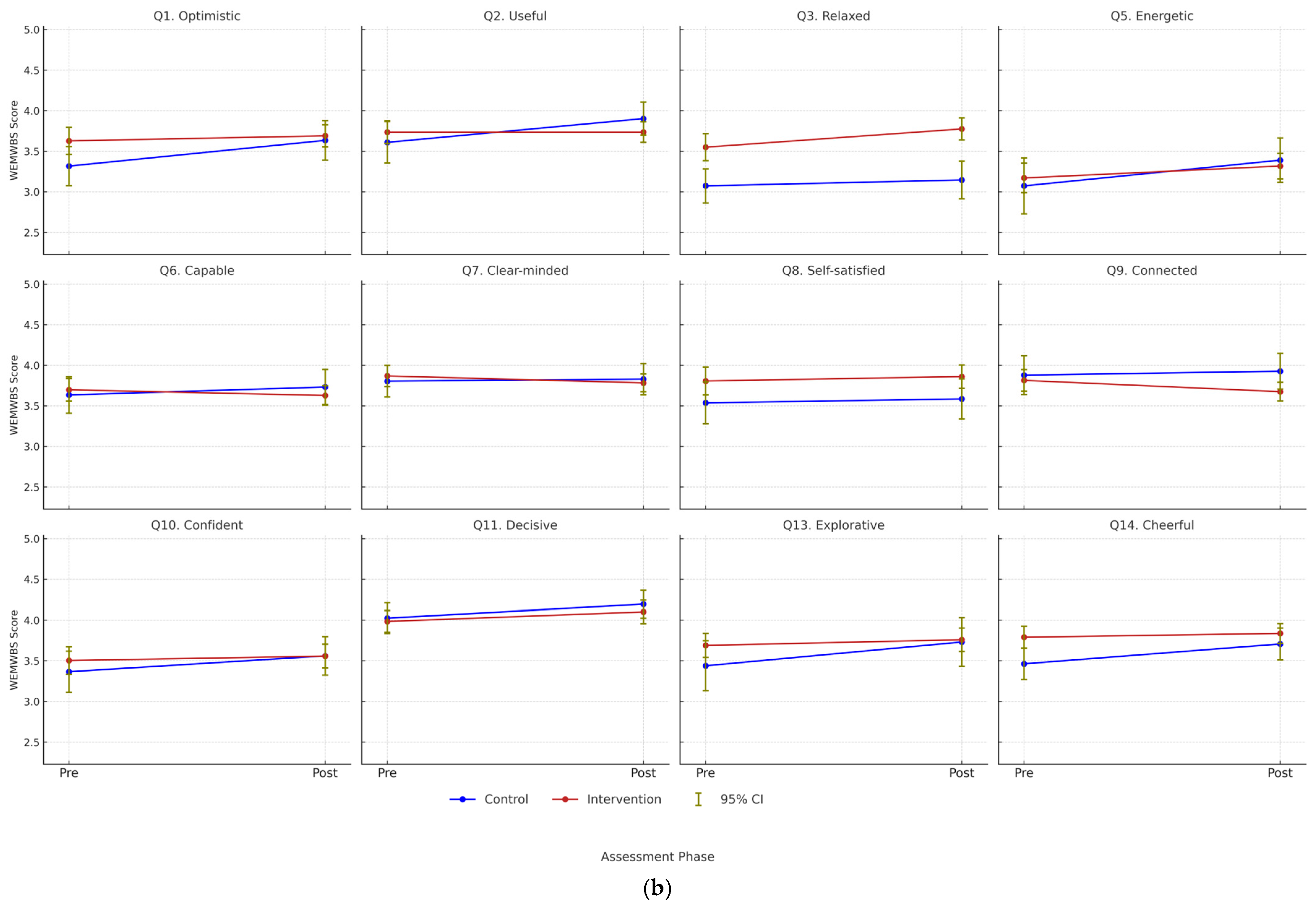

3.2. Two-Way Repeated Measures ANOVA Analysis

3.2.1. Main Effect of Group

3.2.2. Main Effect of Time

3.2.3. Main Effect of Sex

3.2.4. Interaction Effect Between Group and Time

4. Discussion

4.1. Potential Influence of Seasonal Variations

4.2. Baseline Effect and Ceiling Effect

4.3. Sensitivity of the WEMWBS

4.4. Duration and Dosage of the PA Intervention

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PA | Physical Activities |

| WEMWBS | Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

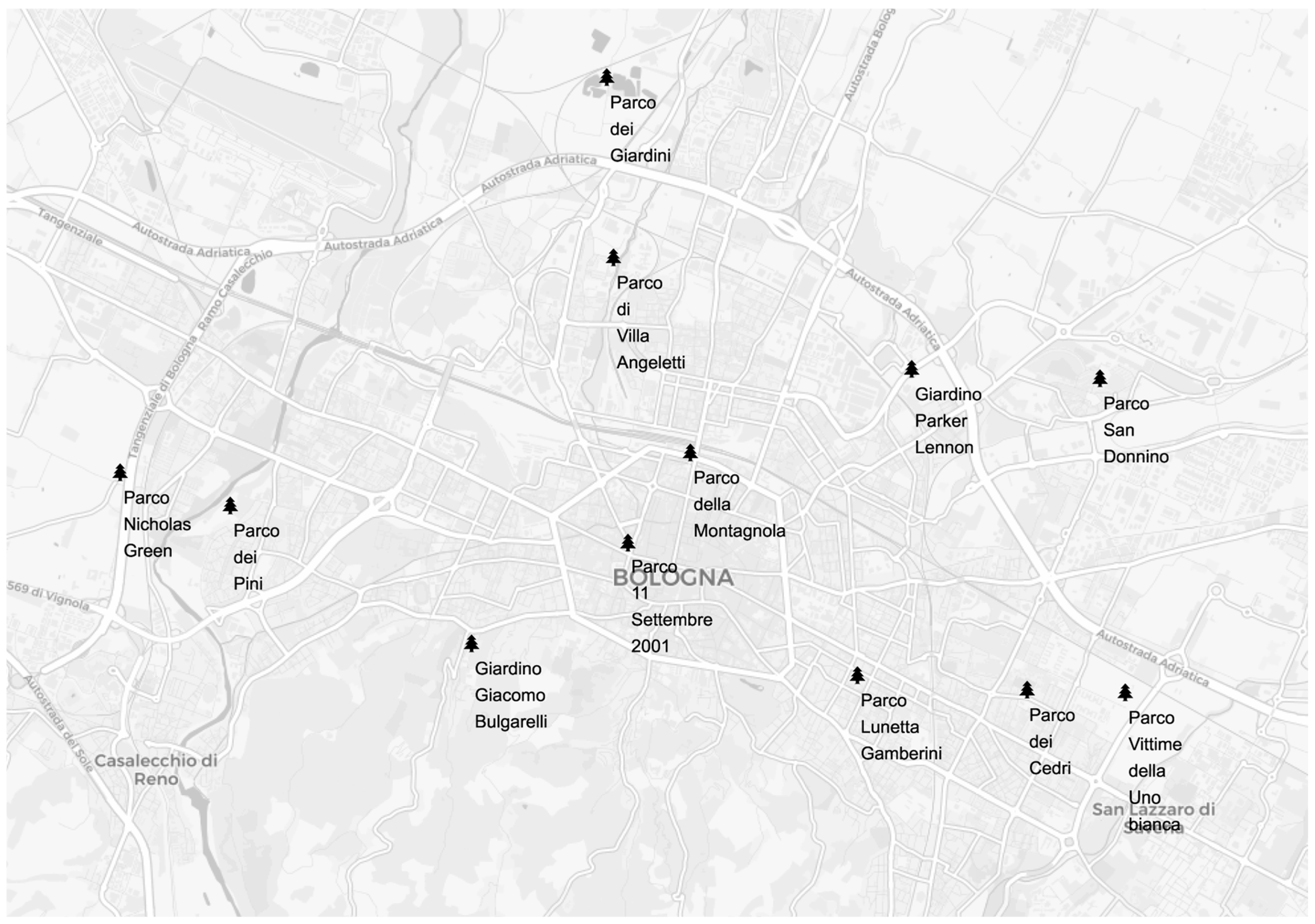

- Parco dei Cedri (District Savena)Covering approximately 11 hectares, this park is one of Bologna’s main green areas, located in the Savena district along the Savena River and inaugurated between the 1970s and 1980s. The park boasts a rich variety of plant species such as cedars, pines, and firs, and includes visitor amenities such as a children’s playground, benches, and water fountains.

- Parco Vittime della Uno bianca (District Savena)This park is a significant memorial park, located in Bologna, with a solemn monument dedicated to the 24 victims who tragically lost their lives due to the criminal activities of the “Banda della Uno Bianca” between 1987 and 1994. Beyond its role as a memorial, the park functions as a community space for public events and activities.

- Parco della Montagnola (District Santo Stefano)Covering an area of 6 hectares, this park is the oldest public park in the city, inaugurated in 1662. Over the centuries, the park has undergone various transformations, including the adoption of a French-style garden design in the 19th century. Today, the park features wide avenues, a central fountain, and a monumental staircase that offers a panoramic view of the city.

- Parco Lunetta Gamberini (District Santo Stefano)Covering approximately 14.5 hectares, the Giardino Lunetta Gamberini is a large public park that hosts several facilities for all ages, including four school complexes, a sports centre, and children’s playgrounds. The park is surrounded by a dense mixed hedge made up of Judas trees, forsythia, blood plums, spiny brooms, and other ornamental shrubs, which shield it from surrounding traffic noise. Easily accessible, this green area is a reference point for both residents and visitors for relaxing, sports, and socialising.

- Parco San Donnino (District San Donato-San Vitale)Inaugurated in 2013, the Parco San Donnino is a large green space created through collaboration between residents, associations, and institutions to provide a place for gathering and well-being. With its 14.5 hectares, the park offers expansive green spaces for outdoor activities, including an outdoor gym dedicated to callisthenics and street workout.

- Giardino Parker Lennon (District San Donato-San Vitale)Covering approximately 4.8 hectares, the Giardino Parker Lennon, known also as the Giardino Charlie Parker—John Lennon, offers green spaces, sport facilities, and cultural activities for residents and visitors. In recent years, the park has undergone revitalization efforts thanks to collaboration between citizens, associations, and local institutions. Improvements have been made to lighting, security, and park maintenance, with the goal of making the space more liveable and welcoming to the community.

- Parco di Villa Angeletti (District Navile)Situated along the right bank of the Navile Canal, this 8.5-hectare park features wide open meadows, wooded areas with native broadleaf trees, and a tinwork of cycling paths. The park preserves the natural morphology of the area, with fruit trees and native vegetation along the canal.

- Parco dei Giardini (District Navile)Covering approximately 9 hectares, this park is a large green space located bewteen Via dell’Arcoveggio and Via dei Giardini, near the historic centre of Corticella. Created in 1990s, the park is an important green lung for the city with many trees, a central pond, children’s play areas and fitness trails.

- Parco 11 Settembre 2001 (District Porto—Saragozza)Located in the heart of Bologna, this park covers an area of about 2 hectares, offering children’s play area and dogs area. The park is a peaceful and social green space, ideal for families, students and anyone looking to enjoy a moment of relaxation outdoors.

- Giardino Giacomo Bulgarelli (District Porto—Saragozza)Covering approximately an area of 3.3 hectares, this urban park is inaugurated in 2015 and named in honour of the legendary captain of Bologna F.C. The park provides wide grassy spaces with a variety of vegetation and sports areas for outdoor activities.

- Parco Nicholas Green (District Borgo Panigale—Reno)With its 8 hectares, the Parco Nicholas Green is a recreational park equipped with various sports facilities, including a basketball court, a skating ring, a football field, and a bocce court. Furthermore, multiple playgrounds are available, making it an ideal spot for families with children. For relaxing and social gatherings, the park offers benches and fountains.

- Parco dei Pini (District Borgo Panigale—Reno)Covering approximately 4 hectares, the park is located on an area that originally belonged to the municipal aqueduct. The park is characterised by a dense and constant tree cover: the name of the park comes from the large number of domestic and maritime pine trees. Furthermore, this green area offers playgrounds for children, benches, drinking fountains, and tree-lined paths.

Appendix B

| Parks and Activities | Parco Nicholas Green | Parco di Villa Angeletti | Parco Della Montagnola | Parco San Donnino | Parco dei Cedri | Giardino Lunetta Gamberini | Parco Vittime Della Uno Bianca | Giardino Parker Lennon | Parco dei Giardini | Giardino Giacomo Bulgarelli | Parco 11 Settembre 2001 | Parco dei Pini |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aikido | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Aerial Silks | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Argentine Tango | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - |

| Badminton | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Belly Dancing | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Body Weight Training | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Body–Mind Energy Balance | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Capoeira | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - |

| Contemporary Dance | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Contemporary Dance Kids | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Creative and Movement Workshops | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cxworx | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Dance | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | - |

| Feldenkrais | - | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - |

| Functional Training | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - |

| Gentle Gymnastics | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - |

| Gymnastics | - | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ |

| Gyrokinesis | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - |

| Handstand Training | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - |

| Judo Games | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Juggling | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - |

| Karate | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Kinesis | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - |

| Krav Maga | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Kung Fu | - | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - |

| Low-Intensity Movement | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Meditation | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - |

| Morning Stretching | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Multisport Activities | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Muscle Strengthening | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Nordic Walking | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ |

| Orienteering | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pilates | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Popular Fitness | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Postural Gymnastics | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - |

| Pre-boxing Training | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - |

| Power Hit | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Qi Gong | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - |

| Rugby | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Run Game | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Self Defence | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Stretching | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Tabata | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Tai Chi | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | - |

| Tone Up | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total Body | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - |

| Ultimate Frisbee | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ |

| Walking | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - |

| Walking and English talking | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Wing Tsun | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yoga | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - |

References

- Karageorghis, C.I.; Bird, J.M.; Hutchinson, J.C.; Hamer, M.; Delevoye-Turrell, Y.N.; Guérin, S.M.; Mullin, E.M.; Mellano, K.T.; Parsons-Smith, R.L.; Terry, V.R. Physical activity and mental well-being under COVID-19 lockdown: A cross-sectional multination study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, J.; McDowell, C.; Lansing, J.; Brower, C.; Smith, L.; Tully, M.; Herring, M. Changes in physical activity and sedentary behavior in response to COVID-19 and their associations with mental health in 3052 US adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.P.; Zuanazzi, A.C.; Salvador, A.P.; Jaloto, A.; Pianowski, G.; Carvalho, L.d.F. Preliminary findings on the associations between mental health indicators and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch. Psychiatry Psychother. 2020, 22, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging, Evidence, Practice; Summary Report; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dore, I.; Caron, J. Mental health: Concepts, measures, determinants. Sante Ment. Au Que. 2017, 42, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, L.; Frank, C.J. Social Determinants of Mental and Behavioral Health. Prim. Care Clin. Off. Pract. 2023, 50, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkin, A.; Goldblatt, P.; Allen, J.; Nathanson, V.; Marmot, M. Global action on the social determinants of health. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e000603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Mavoa, S.; Zhao, J.; Raphael, D.; Smith, M. The association between green space and adolescents’ mental well-being: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, R. Does access to green space impact the mental well-being of children: A systematic review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017, 37, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlden, V.; Weich, S.; Porto de Albuquerque, J.; Jarvis, S.; Rees, K. The relationship between greenspace and the mental wellbeing of adults: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; De Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory. Handb. Theor. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 1, 416–436. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.S.; Maillet, M.A.; Grouzet, F.M. Why do individuals engage with the natural world? A self-determination theory perspective on the effect of nature engagement and well-being. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2022, 17, 1501–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanipekun, A.O.; Chan, A.P.; Xia, B.; Adedokun, O.A. Applying the self-determination theory (SDT) to explain the levels of motivation for adopting green building. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2018, 18, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, H.; White, M.P.; Wheeler, B.W.; Bethel, A.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Nikolaou, V.; Garside, R. Attention Restoration Theory: A systematic review of the attention restoration potential of exposure to natural environments. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 2016, 19, 305–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, M.P.; Schilhab, T.; Bentsen, P. Attention Restoration Theory II: A systematic review to clarify attention processes affected by exposure to natural environments. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 2018, 21, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Browning, M.H.; Rigolon, A.; Larson, L.R.; Taff, D.; Labib, S.; Benfield, J.; Yuan, S.; McAnirlin, O.; Hatami, N. Beyond “bluespace” and “greenspace”: A narrative review of possible health benefits from exposure to other natural landscapes. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 159292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhee, J.S.; French, D.P.; Jackson, D.; Nazroo, J.; Pendleton, N.; Degens, H. Physical activity in older age: Perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. Biogerontology 2016, 17, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahindru, A.; Patil, P.; Agrawal, V. Role of physical activity on mental health and well-being: A review. Cureus 2023, 15, e33475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahart, I.; Darcy, P.; Gidlow, C.; Calogiuri, G. The effects of green exercise on physical and mental wellbeing: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, M.; Brown, D.K.; Sandercock, G.; Wooller, J.-J.; Barton, J. A comparison of four typical green exercise environments and prediction of psychological health outcomes. Perspect. Public Health 2016, 136, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Hooper, P.; Foster, S.; Bull, F. Public green spaces and positive mental health—Investigating the relationship between access, quantity and types of parks and mental wellbeing. Health Place 2017, 48, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Xiong, J.; Qin, H.; Hu, J.; Deng, J.; Han, G.; Yan, J. Influence of thermal comfort of green spaces on physical activity: Empirical study in an urban park in Chongqing, China. Build. Environ. 2022, 219, 109168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarda-Saavedra, P.; Munoz-Quezada, M.T.; Cortinez-O’Ryan, A.; Aguilar-Farias, N.; Vargas-Gaete, R. Benefits of green spaces and physical activity for the well-being and health of people. Rev. Medica De Chile 2022, 150, 1095–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creasy, S.A.; Rogers, R.J.; Davis, K.K.; Gibbs, B.B.; Kershaw, E.E.; Jakicic, J.M. Effects of supervised and unsupervised physical activity programmes for weight loss. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2017, 3, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, C.; Peroutky, K.; Glickman, E. Effects of supervised training compared to unsupervised training on physical activity, muscular endurance, and cardiovascular parameters. MOJ Orthop. Rheumatol. 2016, 5, 00184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Redondo, P.; Valenzuela, P.L.; Morales, J.S.; Ara, I.; Mañas, A. Supervised Versus Unsupervised Exercise for the Improvement of Physical Function and Well-Being Outcomes in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Sports Med. 2024, 54, 1877–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, J.L.A.D.S.; Biduski, D.; Bellei, E.A.; Becker, O.H.C.; Daroit, L.; Pasqualotti, A.; Tourinho Filho, H.; De Marchi, A.C.B. A bowling exergame to improve functional capacity in older adults: Co-design, development, and testing to compare the progress of playing alone versus playing with peers. JMIR Serious Games 2021, 9, e23423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Riemenschneider, F.; Petrunoff, N.; Yao, J.; Ng, A.; Sia, A.; Ramiah, A.; Wong, M.; Han, J.; Tai, B.C.; Uijtdewilligen, L. Effectiveness of prescribing physical activity in parks to improve health and wellbeing-the park prescription randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, R.F.; Christian, H.; Veitch, J.; Astell-Burt, T.; Hipp, J.A.; Schipperijn, J. The impact of interventions to promote physical activity in urban green space: A systematic review and recommendations for future research. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 124, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendelboe-Nelson, C.; Kelly, S.; Kennedy, M.; Cherrie, J.W. A scoping review mapping research on green space and associated mental health benefits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Marini, S.; Mauro, M.; Maietta Latessa, P.; Grigoletto, A.; Toselli, S. Associations Between Urban Green Space Quality and Mental Wellbeing: Systematic Review. Land 2025, 14, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremigni, P.; Stewart-Brown, S.L. Measuring mental well-being: Italian validation of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS). G. Ital. Psicol. 2011, 38, 485–508. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant, R.; Hiller, L.; Fishwick, R.; Platt, S.; Joseph, S.; Weich, S.; Parkinson, J.; Secker, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coventry, P.A.; Brown, J.E.; Pervin, J.; Brabyn, S.; Pateman, R.; Breedvelt, J.; Gilbody, S.; Stancliffe, R.; McEachan, R.; White, P.L. Nature-based outdoor activities for mental and physical health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. SSM Popul. Health 2021, 16, 100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, M.; Wood, C.; Pretty, J.; Schoenmakers, P.; Bloomfield, D.; Barton, J. Regular doses of nature: The efficacy of green exercise interventions for mental wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, W.; Cheng, B.; Feng, X.; Zhuang, X. Relationship between urban green space and mental health in older adults: Mediating role of relative deprivation, physical activity, and social trust. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1442560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Volkow, N.D. Seasonality of brain function: Role in psychiatric disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.; Lawrance, E.L.; Roberts, L.F.; Grailey, K.; Ashrafian, H.; Maheswaran, H.; Toledano, M.B.; Darzi, A. Ambient temperature and mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e580–e589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Tan, X. The effects of temperature on mental health: Evidence from China. J. Popul. Econ. 2023, 36, 1293–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradovich, N.; Migliorini, R.; Paulus, M.P.; Rahwan, I. Empirical evidence of mental health risks posed by climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 10953–10958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rony, M.K.K.; Alamgir, H.M. High temperatures on mental health: Recognizing the association and the need for proactive strategies—A perspective. Health Sci. Rep. 2023, 6, e1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garriga, A.; Sempere-Rubio, N.; Molina-Prados, M.J.; Faubel, R. Impact of seasonality on physical activity: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.-T.; Wu, P.-J.; Peng, C.-Y.J. Accounting for baseline trends in intervention studies: Methods, effect sizes, and software. Cogent Psychol. 2019, 6, 1679941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, J.; Lundin, A.; Johansson, M. An off-target scale limits the utility of Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS) as a measure of well-being in public health surveys. Public Health 2022, 202, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toselli, S.; Bragonzoni, L.; Grigoletto, A.; Masini, A.; Marini, S.; Barone, G.; Pinelli, E.; Zinno, R.; Mauro, M.; Pilone, P.L.; et al. Effect of a Park-Based Physical Activity Intervention on Psychological Wellbeing at the Time of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toselli, S.; Bragonzoni, L.; Dallolio, L.; Alessia, G.; Masini, A.; Marini, S.; Barone, G.; Pinelli, E.; Zinno, R.; Mauro, M.; et al. The Effects of Park Based Interventions on Health: The Italian Project “Moving Parks”. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.L.; Audrey, S.; Gunnell, D.; Cooper, A.; Campbell, R. The relationship between physical activity, mental wellbeing and symptoms of mental health disorder in adolescents: A cohort study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Zwan, J.E.; De Vente, W.; Huizink, A.C.; Bögels, S.M.; De Bruin, E.I. Physical activity, mindfulness meditation, or heart rate variability biofeedback for stress reduction: A randomized controlled trial. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2015, 40, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legey, S.; Aquino, F.; Lamego, M.K.; Paes, F.; Nardi, A.E.; Neto, G.M.; Mura, G.; Sancassiani, F.; Rocha, N.; Murillo-Rodriguez, E. Relationship among physical activity level, mood and anxiety states and quality of life in physical education students. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health CP EMH 2017, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magyar, J.L.; Keyes, C.L. Defining, measuring, and applying subjective well-being. In Positive Psychological Assessment: A Handbook of Models and Measures, 2nd ed.; Gallagher, M.W., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. The subjective wellbeing of migrants in Guangzhou, China: The impacts of the social and physical environment. Cities 2017, 60, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.V.; Jones-Harrell, C.; Fan, Y.; Ramaswami, A.; Orlove, B.; Botchwey, N. Understanding subjective well-being: Perspectives from psychology and public health. Public Health Rev. 2020, 41, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, K.; Ciechanowski, L.; Przegalińska, A. Emotional well-being in urban wilderness: Assessing states of calmness and alertness in informal green spaces (igss) with muse—Portable eeg headband. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.; Qassem, M.; Kyriacou, P.A. Wearable, environmental, and smartphone-based passive sensing for mental health monitoring. Front. Digit. Health 2021, 3, 662811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronwald, T.; Velasques, B.; Ribeiro, P.; Machado, S.; Murillo-Rodríguez, E.; Ludyga, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Budde, H. Increasing exercise’s effect on mental health: Exercise intensity does matter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E11890–E11891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekroud, S.R.; Gueorguieva, R.; Zheutlin, A.B.; Paulus, M.; Krumholz, H.M.; Krystal, J.H.; Chekroud, A.M. Association between physical exercise and mental health in 1·2 million individuals in the USA between 2011 and 2015: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansano-Nadal, O.; Giné-Garriga, M.; Brach, J.S.; Wert, D.M.; Jerez-Roig, J.; Guerra-Balic, M.; Oviedo, G.; Fortuño, J.; Gómara-Toldrà, N.; Soto-Bagaria, L. Exercise-based interventions to enhance long-term sustainability of physical activity in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekkekakis, P.; Parfitt, G.; Petruzzello, S.J. The pleasure and displeasure people feel when they exercise at different intensities: Decennial update and progress towards a tripartite rationale for exercise intensity prescription. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 641–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, S.J.; Asare, M. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: A review of reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Marini, S.; Bragonzoni, L.; Dallolio, L.; Pinelli, E.; Zinno, R.; Astorino, G.; Prosperi, G.; Latessa, P.M.; Mauro, M. Exploring the impact of physical activities on subjective well-being: A cross-sectional study in Bologna, Italy. J. Public Health 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| WEMWBS Dimensions | Control Group | Intervention Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | |||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| Q1. Optimistic | 3.20 ± 0.82 | 3.56 ± 0.92 | 3.50 ± 0.73 | 3.75 ± 0.58 | 3.61 ± 0.96 | 3.67 ± 0.79 | 3.77 ± 1.03 | 3.82 ± 0.81 |

| Q2. Useful | 3.68 ± 0.85 | 3.84 ± 0.69 | 3.50 ± 0.82 | 4.00 ± 0.63 | 3.72 ± 0.79 | 3.74 ± 0.74 | 3.82 ± 0.95 | 3.71 ± 0.69 |

| Q3. Relaxed | 3.08 ± 0.64 | 2.96 ± 0.84 | 3.06 ± 0.77 | 3.44 ± 0.51 | 3.52 ± 0.98 | 3.78 ± 0.80 | 3.77 ± 0.90 | 3.77 ± 0.66 |

| Q5. Energetic | 3.00 ± 1.16 | 3.32 ± 0.95 | 3.19 ± 1.11 | 3.50 ± 0.82 | 3.13 ± 1.09 | 3.29 ± 0.95 | 3.47 ± 0.72 | 3.53 ± 0.51 |

| Q6. Capable | 3.52 ± 0.77 | 3.68 ± 0.63 | 3.81 ± 0.66 | 3.81 ± 0.83 | 3.69 ± 0.83 | 3.61 ± 0.72 | 3.77 ± 0.66 | 3.77 ± 0.56 |

| Q7. Clear-minded | 3.72 ± 0.68 | 3.72 ± 0.61 | 3.94 ± 0.57 | 4.00 ± 0.63 | 3.88 ± 0.76 | 3.79 ± 0.66 | 3.82 ± 0.73 | 3.77 ± 0.44 |

| Q8. Self-satisfied | 3.44 ± 0.92 | 3.56 ± 0.82 | 3.69 ± 0.70 | 3.63 ± 0.81 | 3.81 ± 1.01 | 3.88 ± 0.87 | 3.77 ± 0.90 | 3.71 ± 0.59 |

| Q9. Connected | 3.92 ± 0.91 | 3.96 ± 0.79 | 3.81 ± 0.54 | 3.88 ± 0.62 | 3.81 ± 0.77 | 3.66 ± 0.67 | 3.82 ± 0.81 | 3.77 ± 0.66 |

| Q10. Confident | 3.20 ± 0.91 | 3.36 ± 0.81 | 3.63 ± 0.62 | 3.88 ± 0.62 | 3.49 ± 1.01 | 3.54 ± 0.88 | 3.59 ± 0.80 | 3.71 ± 0.59 |

| Q11. Decisive | 4.00 ± 0.65 | 4.20 ± 0.58 | 4.06 ± 0.57 | 4.19 ± 0.54 | 3.99 ± 0.78 | 4.10 ± 0.85 | 3.94 ± 0.75 | 4.12 ± 0.78 |

| Q13. Explorative | 3.48 ± 1.01 | 3.68 ± 0.99 | 3.38 ± 1.03 | 3.81 ± 0.98 | 3.70 ± 0.87 | 3.77 ± 0.84 | 3.65 ± 0.79 | 3.71 ± 0.77 |

| Q14. Cheerful | 3.44 ± 0.58 | 3.60 ± 0.71 | 3.50 ± 0.73 | 3.88 ± 0.50 | 3.80 ± 0.78 | 3.86 ± 0.72 | 3.77 ± 0.75 | 3.71 ± 0.59 |

| Tot Score | 41.68 ± 6.68 | 43.44 ± 6.65 | 43.06 ± 4.99 | 45.75 ± 5.27 | 44.13 ± 7.93 | 44.67 ± 6.82 | 44.94 ± 7.15 | 45.06 ± 6.10 |

| Main Effect (Group) | Main Effect (Time) | Main Effect (Sex) | Interaction (Group × Time) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WEMWBS Dimensions | F | p | Effect Size (Partial η2) | F | p | Effect Size (Partial η2) | F | p | Effect Size (Partial η2) | F | p | Effect Size (Partial η2) |

| Q1. Optimistic | 2.96 | 0.087 | 0.017 | 5.13 | 0.025 * | 0.030 | 0.57 | 0.450 | 0.003 | 2.32 | 0.129 | 0.014 |

| Q2. Useful | 0.02 | 0.898 | <0.001 | 4.05 | 0.046 * | 0.024 | 0.76 | 0.385 | 0.005 | 4.05 | 0.046 * | 0.024 |

| Q3. Relaxed | 22.7 | <0.001 *** | 0.120 | 2.59 | 0.110 | 0.015 | 0.47 | 0.495 | 0.003 | 0.67 | 0.414 | 0.004 |

| Q5. Energetic | 0.23 | 0.631 | 0.001 | 8.11 | 0.005 ** | 0.046 | 1.62 | 0.205 | 0.010 | 1.91 | 0.169 | 0.011 |

| Q6. Capable | 0.03 | 0.860 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.858 | <0.001 | 0.67 | 0.415 | 0.004 | 1.16 | 0.283 | 0.007 |

| Q7. Clear-minded | 0.07 | 0.787 | <0.001 | 0.19 | 0.662 | 0.001 | 0.83 | 0.363 | 0.005 | 0.62 | 0.431 | 0.004 |

| Q8. Self-satisfied | 3.52 | 0.062 | 0.021 | 0.39 | 0.531 | 0.002 | 0.00 | 1.000 | <0.001 | 0.00 | 0.973 | <0.001 |

| Q9. Connected | 4.50 | 0.036 * | 0.027 | 0.18 | 0.669 | 0.001 | 0.78 | 0.378 | 0.005 | 2.19 | 0.141 | 0.013 |

| Q10. Confident | 0.92 | 0.340 | 0.005 | 2.37 | 0.125 | 0.014 | 0.61 | 0.435 | 0.004 | 0.76 | 0.386 | 0.004 |

| Q11. Decisive | 0.32 | 0.570 | 0.002 | 3.56 | 0.061 | 0.021 | 0.00 | 1.000 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.721 | 0.001 |

| Q13. Explorative | 0.98 | 0.324 | 0.006 | 3.88 | 0.050 | 0.023 | 0.47 | 0.492 | 0.003 | 1.47 | 0.227 | 0.009 |

| Q14. Cheerful | 3.48 | 0.064 | 0.021 | 6.50 | 0.012 * | 0.037 | 0.89 | 0.348 | 0.005 | 3.48 | 0.064 | 0.020 |

| Tot Score | 1.38 | 0.243 | 0.008 | 6.82 | 0.010 ** | 0.039 | 0.89 | 0.346 | 0.005 | 3.32 | 0.070 | 0.019 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Z.; Moro, F.; Baldoni, N.; Mauro, M.; Marini, S.; Bragonzoni, L.; Dallolio, L.; Pinelli, E.; Zinno, R.; Astorino, G.; et al. The Impact of Supervised Physical Activity in Urban Green Spaces on Mental Well-Being Among Middle-Aged Adults: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060192

Xu Z, Moro F, Baldoni N, Mauro M, Marini S, Bragonzoni L, Dallolio L, Pinelli E, Zinno R, Astorino G, et al. The Impact of Supervised Physical Activity in Urban Green Spaces on Mental Well-Being Among Middle-Aged Adults: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Urban Science. 2025; 9(6):192. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060192

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Zhengyang, Federica Moro, Niccolò Baldoni, Mario Mauro, Sofia Marini, Laura Bragonzoni, Laura Dallolio, Erika Pinelli, Raffaele Zinno, Gerardo Astorino, and et al. 2025. "The Impact of Supervised Physical Activity in Urban Green Spaces on Mental Well-Being Among Middle-Aged Adults: A Quasi-Experimental Study" Urban Science 9, no. 6: 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060192

APA StyleXu, Z., Moro, F., Baldoni, N., Mauro, M., Marini, S., Bragonzoni, L., Dallolio, L., Pinelli, E., Zinno, R., Astorino, G., Prosperi, G., Maietta Latessa, P., & Toselli, S. (2025). The Impact of Supervised Physical Activity in Urban Green Spaces on Mental Well-Being Among Middle-Aged Adults: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Urban Science, 9(6), 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060192