AI-Driven Deconstruction of Urban Regulatory Frameworks: Unveiling Social Sustainability Gaps in Santiago’s Communal Zoning

Abstract

1. Introduction

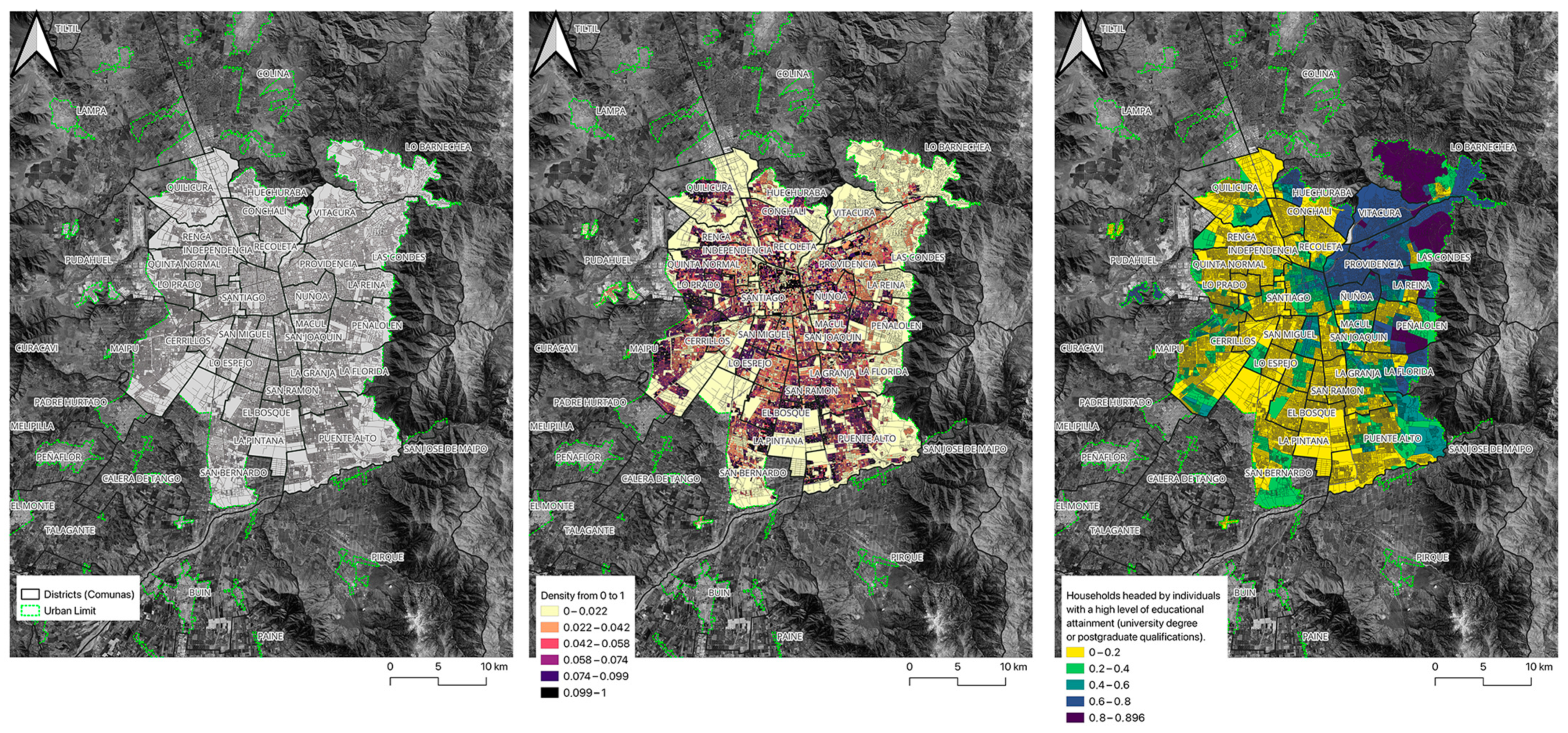

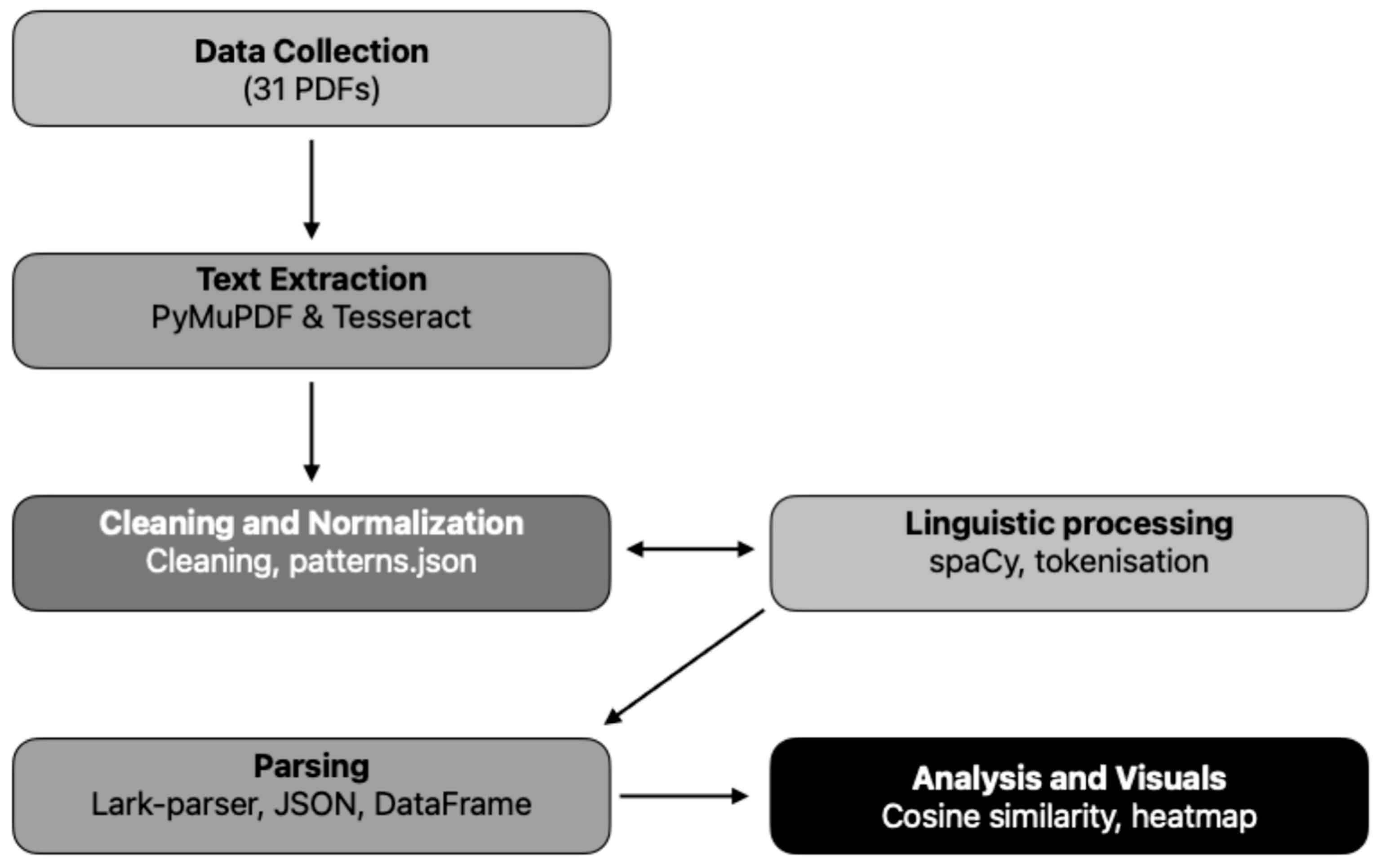

2. Materials and Methods

- Estación Central

- Pedro Aguirre Cerda

3. Results

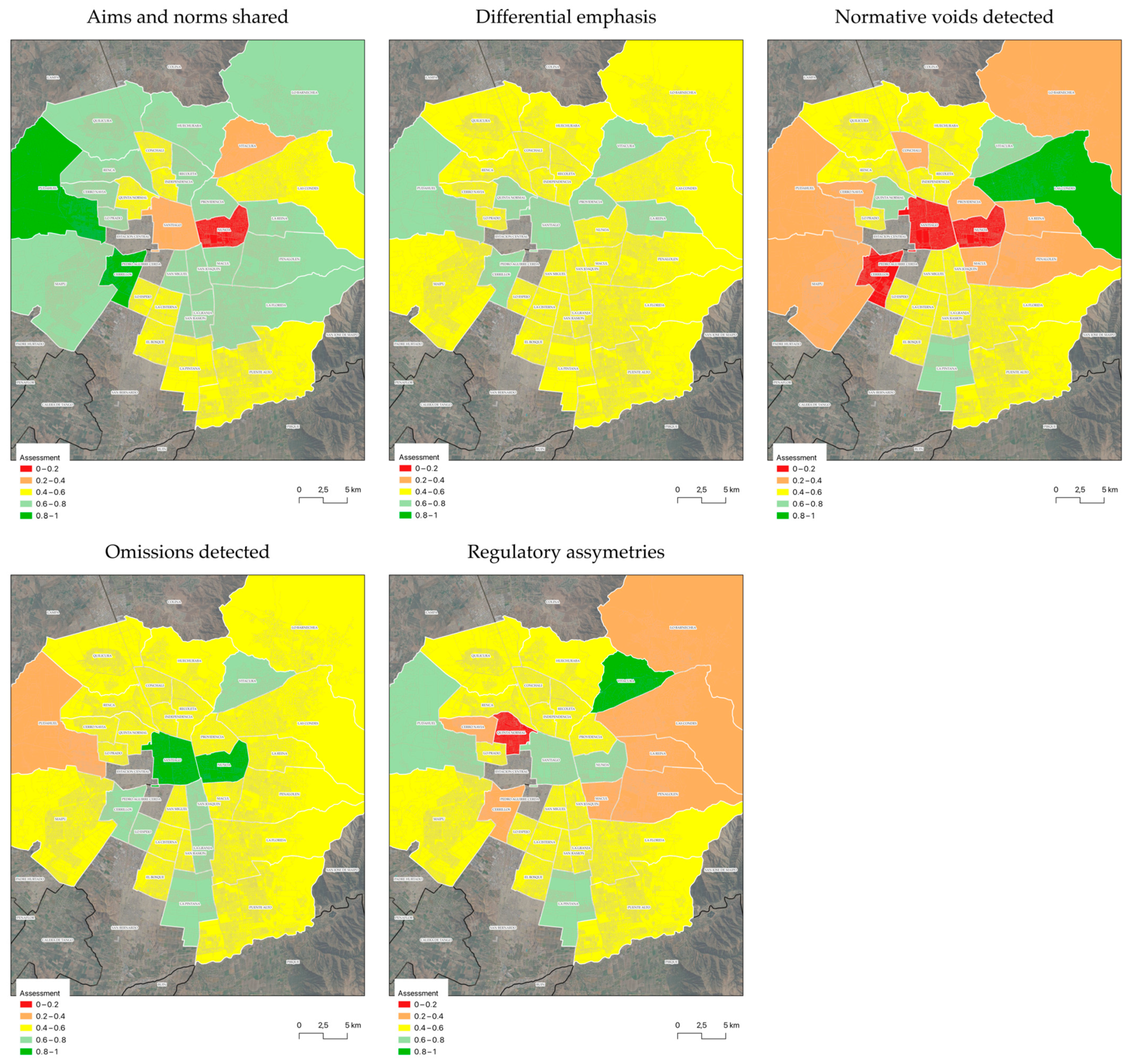

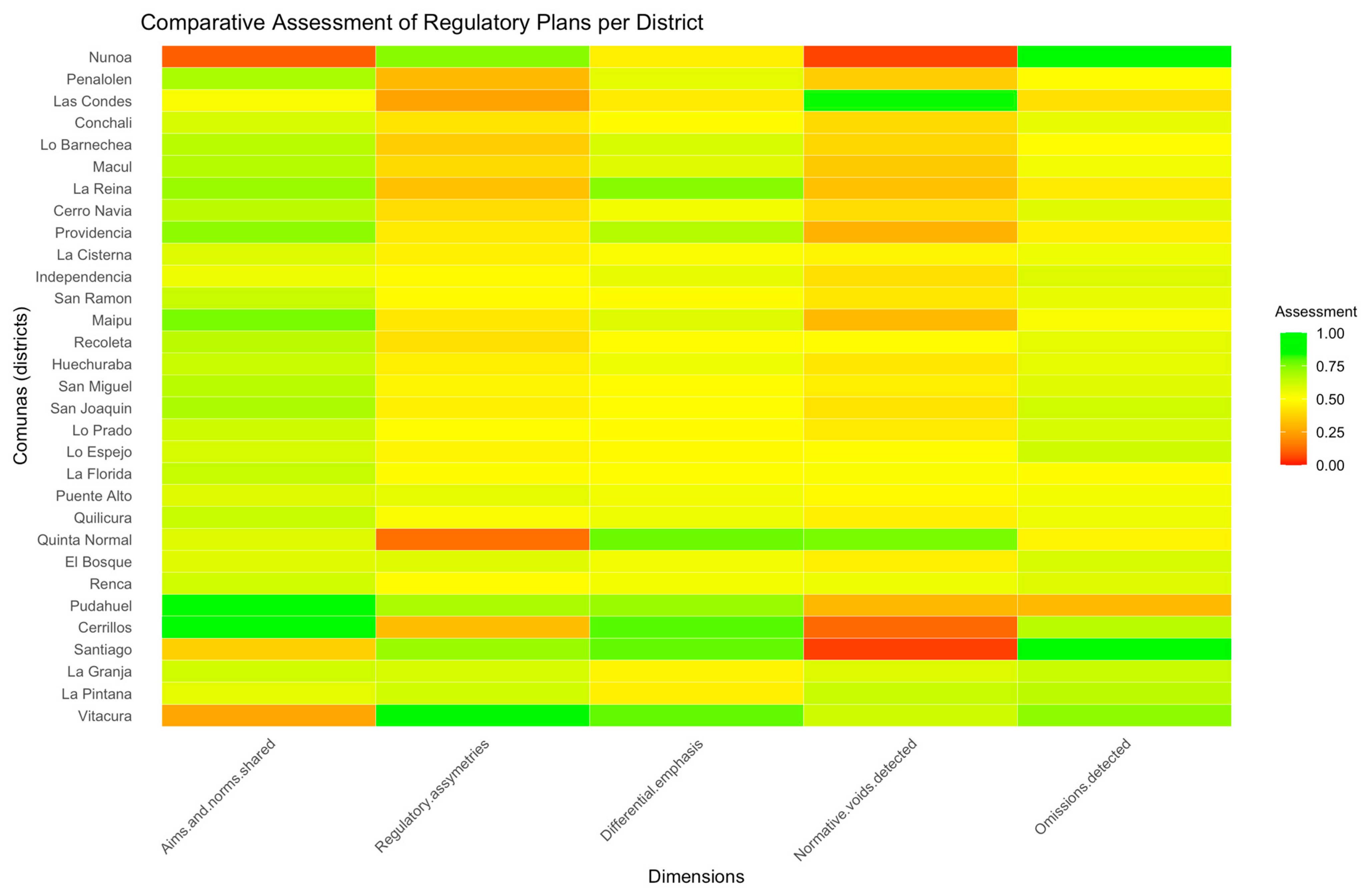

3.1. Shared Objectives and Regulatory Elements

- Zoning: All municipalities delineate preferential use zones (residential, commercial, industrial, or service), sub-zones, and special areas, explicitly defining permitted, conditional, and prohibited uses. Zoning seeks to ensure compatibility among urban activities and prevent land use conflicts.

- Building conditions: Regulations regarding floor area ratios, maximum building heights, setbacks, and front gardens are applied across all ordinances to control urban morphology, safeguard public space quality, and mitigate negative externalities associated with uncontrolled densification.

- Public space and road infrastructure regulations: All PRCs include provisions regarding structural road systems, parking requirements, vehicular access, and standards for green areas.

- Additionally, the ordinances are aligned with metropolitan-scale planning instruments, particularly the Santiago Metropolitan Regulatory Plan (PRMS), ensuring some level of coherence in matters such as metropolitan uses, protected or risk-prone areas, and inter-communal facilities.

3.2. Asymmetries in Regulation

- (a) Highly Regulated CommunesMunicipalities such as Las Condes, La Reina, and Macul exhibit highly detailed regulations, with remarkable specificity. For instance, La Reina has established a system of normative incentives that rewards projects that install underground electricity and telecommunications infrastructure, offering benefits in floor area ratios and land occupation coefficients. These communes also enforce strict controls over public space, regulating front gardens, fencing, and parking to preserve urban image and quality of life. Furthermore, they display explicit concern for the integration of high-standard public services, detailing technical requirements for educational, healthcare, and commercial facilities, including specific parking provisions and traffic impact assessments. While they allow higher residential densities in strategic areas, these are conditioned on strict compliance with standards of accessibility, open space, and public amenities.

- (b) Peripheral and Less Regulated CommunesBy contrast, municipalities such as La Pintana, Puente Alto, San Bernardo, and La Granja adopt more basic regulatory frameworks, focusing primarily on defining land uses and controlling densities, but lacking sophisticated instruments for incentives or integration. Residential density regulations tend to be restrictive, with low maximum thresholds aimed at avoiding infrastructure overload, yet inadvertently limiting housing diversification and social integration initiatives. Public space and green area provisions are more generic, with less emphasis on quality, continuity, or maintenance. These communes also lack strong regulatory mechanisms to attract investment in essential urban infrastructure (e.g., schools, healthcare, commerce), which exacerbates disparities in access to basic services.

- (c) Intermediate Regulation CommunesMunicipalities such as Maipú, San Joaquín, and Quilicura fall into an intermediate category. Their ordinances demonstrate concern with rapid urban growth, incorporating feasibility studies on infrastructure and traffic, and seeking to control unplanned expansion. However, they still lack clear instruments to link densification with the provision of social infrastructure and services—an omission that may lead to future issues with overcrowded facilities and deficits in public space provision.

3.3. Differentiated Emphases

3.4. Detected Regulatory Gaps

- Lack of normative integration for social housing in consolidated areas: With few exceptions, there are no clear requirements or incentives for locating social housing in well-served or central zones, thereby perpetuating urban segregation.

- Weak metropolitan coordination: The ordinances do not include inter-communal mechanisms for the planning and financing of major facilities (e.g., education, health, transport), resulting in significant disparities in service provision.

- Absence of explicit regulation on resilience and climate change: Although some areas are restricted due to natural hazards, there are no integrated strategies for climate adaptation, such as green infrastructure, energy efficiency, or urban heat island mitigation.

- Limited reference to universal accessibility and inclusive standards: The ordinances largely omit specific requirements to ensure physical and social accessibility in urban space, reflecting a normative blind spot with regard to social sustainability. The blind spots identified create an opportunity to foster discussions aimed at strengthening the requirements for communal regulatory plans. Such discussions typically occur among experts in conjunction with the Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning and may subsequently inform draft legislation submitted to the national congress. However, these processes often exhibit limitations in their capacity to produce comprehensive diagnoses of systemic regulatory challenges. The analytical tools presented here offer the potential to generate more holistic perspectives, thereby supporting a more sustained and informed progression of reform efforts.

3.5. Anticipated Future Challenges

- Key Omissions Identified:

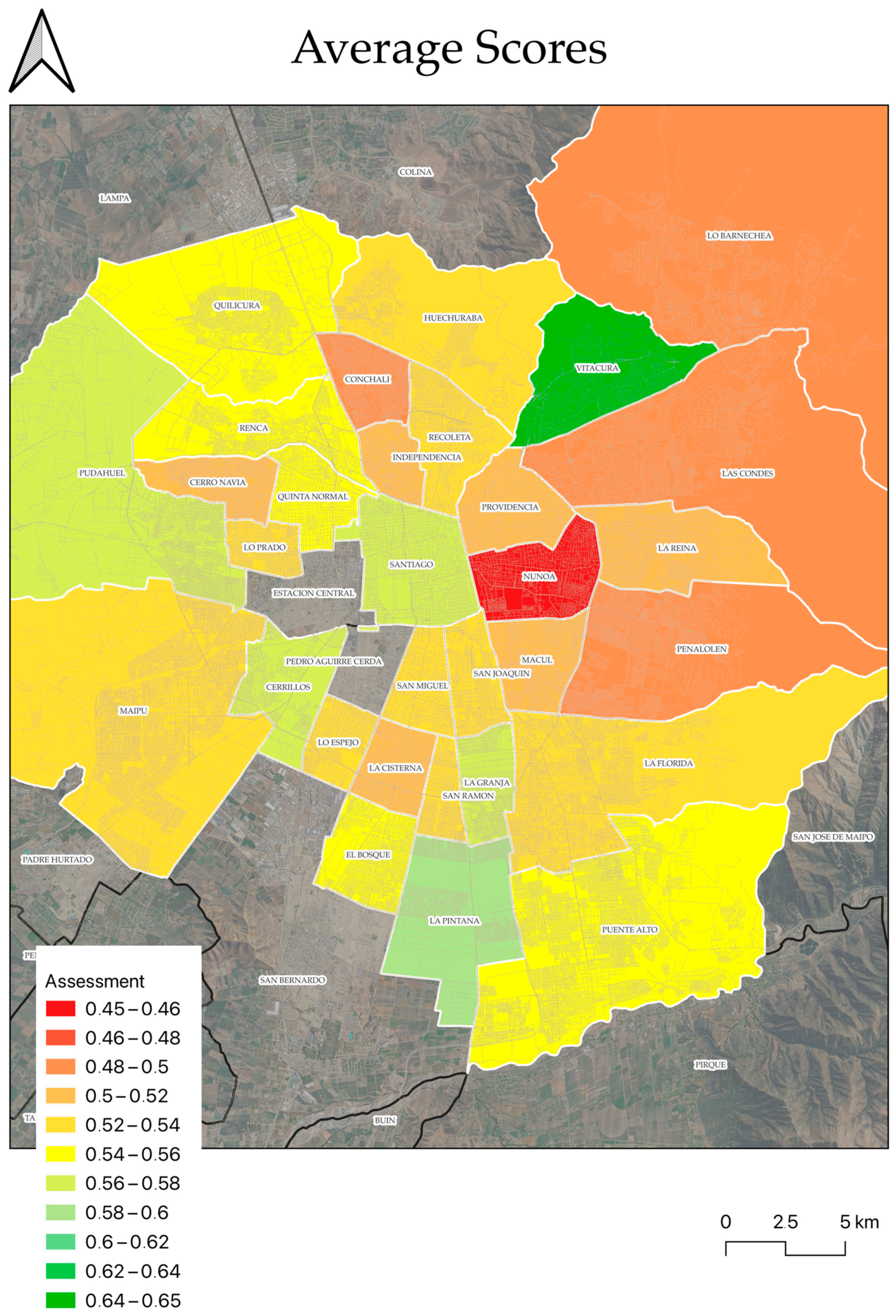

3.6. Cartographic Synthesis and Interpretation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Table of Ordinances

| Municipality | Latest Update (Year) | Promulgation |

| Cerro Navia | 2019 | Decreto 1.760—Actualización PRC Cerro Navia, D.O. 13-12-2019 oaicite:0 |

| Conchalí | 2006 | Decreto 1.274—PRC Conchalí, D.O. 29-05-2006 (LeyChile) oaicite:1 |

| El Bosque | 2007 | D.O. 11-07-2007 (LeyChile) (see SEREMI RM archive) |

| Huechuraba | 2018 | Actualización PRC Huechuraba, D.O. 18-04-2018 (LeyChile) |

| Independencia | 2017 | Decreto 1.432—Actualización PRC Independencia, D.O. 22-02-2017 (LeyChile) |

| La Cisterna | 2015 | Decreto 1.210—Actualización PRC La Cisterna, D.O. 05-06-2015 (LeyChile) |

| La Florida | 2012 | Decreto 1.017—PRC La Florida, D.O. 10-10-2012 (LeyChile) |

| La Granja | 2019 | Decreto 2.045—Actualización PRC La Granja, D.O. 21-11-2019 (LeyChile) |

| La Pintana | 2020 | Decreto 2.160—Actualización PRC La Pintana, D.O. 15-12-2020 (LeyChile) |

| La Reina | 2018 | Decreto 1.576—Actualización PRC La Reina, D.O. 30-08-2018 (LeyChile) |

| Las Condes | 2014 | Decreto 1.354—Actualización PRC Las Condes, D.O. 12-12-2014 (LeyChile) |

| Lo Barnechea | 2013 | Decreto 1.295—PRC Lo Barnechea, D.O. 05-11-2013 (LeyChile) |

| Lo Espejo | 2016 | Decreto 1.498—Actualización PRC Lo Espejo, D.O. 17-05-2016 (LeyChile) |

| Lo Prado | 2011 | Decreto 942—PRC Lo Prado, D.O. 08-09-2011 (LeyChile) |

| Macul | 2017 | Decreto 1.410—Actualización PRC Macul, D.O. 05-03-2017 (LeyChile) |

| Maipú | 2019 | Decreto 2.005—Actualización PRC Maipú, D.O. 02-10-2019 (LeyChile) |

| Ñuñoa | 2013 | Decreto 1.280—Actualización PRC Ñuñoa, D.O. 20-02-2013 (LeyChile) |

| Peñalolén | 2014 | Decreto 1.346—Actualización PRC Peñalolén, D.O. 26-09-2014 (LeyChile) |

| Providencia | 2016 | Decreto 1.523—Actualización PRC Providencia, D.O. 10-11-2016 (LeyChile) |

| Pudahuel | 2018 | Decreto 1.601—Actualización PRC Pudahuel, D.O. 25-11-2018 (LeyChile) |

| Puente Alto | 2015 | Decreto 1.132—Actualización PRC Puente Alto, D.O. 18-04-2015 (LeyChile) |

| Quilicura | 2020 | Decreto 2.203—Actualización PRC Quilicura, D.O. 04-12-2020 (LeyChile) |

| Quinta Normal | 2012 | Decreto 1.021—PRC Quinta Normal, D.O. 22-10-2012 (LeyChile) |

| Recoleta | 2018 | Decreto 1.595—Actualización PRC Recoleta, D.O. 13-12-2018 (LeyChile) |

| Renca | 2019 | Decreto 1.991—Actualización PRC Renca, D.O. 10-09-2019 (LeyChile) |

| San Joaquín | 2017 | Decreto 1.444—Actualización PRC San Joaquín, D.O. 05-05-2017 (LeyChile) |

| San Miguel | 2013 | Decreto 1.312—PRC San Miguel, D.O. 15-11-2013 (LeyChile) |

| San Ramón | 2016 | Decreto 1.551—PRC San Ramón, D.O. 28-11-2016 (LeyChile) |

| Santiago | 2021 | DEC.Secc.2da Nº 6847 D.O. 02-12- 2021 (Municipalidad Santiago) |

| Vitacura | 2015 | Decreto 1.178—Actualización PRC Vitacura, D.O. 03-09-2015 (LeyChile) |

Appendix B. Methodological Appendix

- Title (regex: ^ORDENANZA\s+.*)

- Chapter (^CAPÍTULO\s+\w+)

- Article (^Artículo\s+\d+)

- Section (^\d+.\d+)

- Clause: remaining paragraph text

References

- Abizadeh, A. Legislature by Lot: Transformative Designs for Deliberative Governance; Gastil, J., Wright, E.O., Eds.; The Real Utopias Project; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-78873-608-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bento, A.M.; Franco, S.F.; Kaffine, D.T. Effectiveness of Housing Revitalization Subsidies in the Presence of Zoning. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2011, 41, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo, R.; Segovia, M.; Wahr, C.; Thenoux, G. Superpave Zoning for Chile. Rev. Ing. Constr. 2017, 32, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves Franca, S.L. Housing public policies in the Urban Expansion Zone of Aracaju-SE, Brazil. In Ciudades En Construccion Permanente: Destino de Casas Para Todos? Vol Ii; Barreto, T.B., Mancilla, M.R., Espinosa, J.E., Eds.; Editorial Univ Abya-Yala: Cuenca, Ecuador, 2015; Volume 2, pp. 279–301. ISBN 978-9942-09-265-6. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, B.R.; Carvalho-Ribeiro, S.M.; Maia-Barbosa, P.M. A Multiscale Analysis of Land Use Dynamics in the Buffer Zone of Rio Doce State Park, Minas Gerais, Brazil. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 935–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjorgjevska, E.; Mirceva, G. Content Engineering for State-of-the-Art SEO Digital Strategies by Using NLP and ML. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Congress on Human-Computer Interaction, Optimization and Robotic Applications (HORA), Ankara, Turkey, 11–13 June 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Linder-Pelz, S.; Hall, L.M. The Theoretical Roots of NLP-Based Coaching. Coach. Psychol. 2007, 3, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dPrix, W.; Schmidbaur, K.; Bolojan, D.; Baseta, E. The Legacy Sketch Machine: From Artificial to Architectural Intelligence. Archit. Des. 2022, 92, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, F.; Kumar, A.; Upadhyay, A.; Chokshi, H.; Trinkūnas, V.; Magda, R. Property Management Enabled by Artificial Intelligence Post COVID-19: An Exploratory Review and Future Propositions. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2022, 26, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M. Natural Language Processing for Urban Research: A Systematic Review. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkley, C.; Stahmer, C. What Is in a Plan? Using Natural Language Processing to Read 461 California City General Plans. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2024, 44, 632–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mleczko, M.; Desmond, M. Using Natural Language Processing to Construct a National Zoning and Land Use Database. Urban Stud. 2023, 60, 2564–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, A.; Mena Valdés, J.A.; Montes Marín, M. Communal development plan: The governing instrument of municipal management in Chile? Revista INVI 2016, 31, 173–200. Available online: https://revistainvi.uchile.cl/index.php/INVI/article/view/62723 (accessed on 1 April 2025). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Navarrete-Hernandez, P.; Toro, F. Urban Systems of Accumulation: Half a Century of Chilean Neoliberal Urban Policies. Antipode 2019, 51, 899–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicuña, M. El marco regulatorio en el contexto de la gestión empresarialista y la mercantilización del desarrollo urbano del Gran Santiago, Chile. Revista INVI 2013, 28, 181–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Río, J.P.A.; del Campo Munnich, M. Governing Pudahuel: Applying Regime Analysis to a Chilean Study Case. JLAE 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stackhouse, J. Urban Land Use and the Entrepreneurial State: A Case Study of Pudahuel, Santiago Chile during the Military Regime (1973–1989). J. Lat. Am. Geogr. 2009, 8, 99–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpaci, J.L.; Infante, R.P.; Gaete, A. Planning Residential Segregation: The Case of Santiago, Chile. Urban Geogr. 1988, 9, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, A.; Bucci, F.; Palma, C.; Munizaga, J.; Montre-Águila, V. Development, Urban Planning and Political Decisions. A Triad That Built Territories at Risk. Nat. Hazards 2021, 109, 1935–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Pulido, J.A.; Mojica, A.; Bruner, A.; Guevara-Sangines, A.; Simon, C.; Vasquez-Lavin, F.; Gonzalez-Baca, C.; Infanzon, M.J. A Business Case for Marine Protected Areas: Economic Valuation of the Reef Attributes of Cozumel Island. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicuña, M. Planificación Metropolitana de Santiago. Rev. Iberoam. Urban. 2017, 13, 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- McCawley, D.G. The Political Economy of Land Use Governance in Santiago, Chile and Its Implications for Class-Based Segregation. SSRN 2012, 47, 119–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegras, C.; Stewart, A.; Forray, R.; Hidalgo, R.; Figueroa, C.; Duarte, F.; Wampler, J. Designing BRT-Oriented Development. In Restructuring Public Transport Through Bus Rapid Transit: An International and Interdisciplinary Perspective; Munoz, J., PagetSeekins, L., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2016; pp. 181–207. ISBN 978-1-4473-2618-2. [Google Scholar]

- Beguin, J.A.P.; Reyes, M.I.P. Los Primeros Planes Intercomunales Metropolitanos de Chile. Volumen I: Los Planes Para Santiago de Chile 1960–1994; Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo Universidad de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2016; ISBN 978-956-8556-05-1. [Google Scholar]

- Vicuña, M.; Urbina-Julio, A. “Alcánzame Si Puedes”: Ajustes y Calibraciones de La Normativa Urbana Tras La Verticalización En El Área Metropolitana de Santiago. Eure 2023, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Morales, E. Gentrification in Santiago, Chile: A Property-Led Process of Dispossession and Exclusion. Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 1109–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Morales, E.J. Real Estate Market, State-Entrepreneurialism and Urban Policy in the “gentrification by Ground Rent Dispossession” of Santiago de Chile. J. Lat. Am. Geogr. 2010, 9, 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pablo, P.; Andrea, B.; Gonzalo, P.-V.; Emilio, M. La evaluación del espacio público de ciudades intermedias de Chile desde la perspectiva de sus habitantes: Implicaciones para la intervención urbana. Territorios 2018, 39, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlack, E.; Vicuna, M. Highly Influential Normative Components Regarding the New Morphology of Metropolitan Santiago: A Critical Review of “Harmonic Set”. Eure-Rev. Latinoam. Estud. Urbano Reg. 2011, 37, 131–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicuña, M.; Pumarino, N.; Urbina, A. Payment for Impacts in Intensive Residential Densification Projects in the Metropolitan Area of Santiago: Critical Analysis of the New Chilean Legislation of Contributions to Public Space [Pago Por Impactos En Proyectos de Densificación Residencial Intens. Eure 2020, 46, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, R.; Alvarado, V.; Volker, P.; Arenas, F.; Salazar, A. Metropolitan Coastal Planning in Chile: From a Regulation Prospect to a Coopted Planning (1965–2014) [Ordenamento Litorâneo Metropolitano No Chile: Da Expetativa de Regulamentação Para o Planejamento Cooptado (1965–2014)]. Cuad. Vivienda Urban. 2015, 8, 206–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliste, E.; di Méo, G.; Guerrero, R. Ideologies behind the Development and Construction of the Metropolitan Area of Concepción (Chile). Ann. Geogr. 2013, 123, 662–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, C.; Gómez, R.; Hidalgo, R. Expresión Territorial de La Fragmentación y Segregación; Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos: Cuernavaca, Mexico, 2016; ISBN 978-607-8434-99-2. [Google Scholar]

- Symmes, L.R. Vertical City: The “New Form” of Precarious Housing Commune of Estación Central, Santiago de Chile [Ciudad Vertical: La “Nueva Forma” de La Precariedad Habitacional Comuna de Estación Central, Santiago de Chile]. Revista 2017, 180, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas Symmes, L.; Cortés Salinas, A.; Moreno, D. Santiago, the Non-City? Destruction, Creation, and Precariousness of Verticalized Space. In Urbicide; Carrión Mena, F., Cepeda Pico, P., Eds.; The Urban Book Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2023; pp. 865–890. ISBN 978-3-031-25303-4. [Google Scholar]

- Mikelionienė, J.; Motiejūnienė, J. Corpus-Based Analysis of Semi-Automatically Extracted Artificial Intelligence-Related Terminology. J. Lang. Cult. Educ. 2021, 9, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vergara-Perucich, J.F. AI-Driven Deconstruction of Urban Regulatory Frameworks: Unveiling Social Sustainability Gaps in Santiago’s Communal Zoning. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060186

Vergara-Perucich JF. AI-Driven Deconstruction of Urban Regulatory Frameworks: Unveiling Social Sustainability Gaps in Santiago’s Communal Zoning. Urban Science. 2025; 9(6):186. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060186

Chicago/Turabian StyleVergara-Perucich, Jose Francisco. 2025. "AI-Driven Deconstruction of Urban Regulatory Frameworks: Unveiling Social Sustainability Gaps in Santiago’s Communal Zoning" Urban Science 9, no. 6: 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060186

APA StyleVergara-Perucich, J. F. (2025). AI-Driven Deconstruction of Urban Regulatory Frameworks: Unveiling Social Sustainability Gaps in Santiago’s Communal Zoning. Urban Science, 9(6), 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9060186