Abstract

This article presents a novel methodology for auditing urban regulatory frameworks through the application of artificial intelligence (AI) using the case of Greater Santiago as an empirical laboratory. Based on the semantic analysis of 31 communal zoning ordinances (Planes Reguladores Comunales, PRCs), the study uncovers how legal structures actively reproduce socio-spatial inequalities under the guise of normative neutrality. The DeepSeek-R1 model, fine-tuned for Chilean legal-urban discourse, was used, enabling the detection of normative asymmetries, omissions, and structural fragmentation. Key findings indicate that affluent communes, such as Vitacura and Las Condes, display detailed and incentive-rich regulations, while peripheral municipalities lack provisions for social housing, participatory mechanisms, or climate resilience, thereby reinforcing exclusionary patterns. The analysis also introduces a scalable rubric-based evaluation system and GIS visualizations to synthetize regulatory disparities across the metropolitan area. Methodologically, the study shows how domain-adapted AI can extend regulatory scrutiny beyond manual limitations, while substantively contributing to debates on spatial justice, institutional fragmentation, and regulatory opacity in urban planning. The results call for binding mechanisms that align local zoning with metropolitan equity goals and highlight the potential of automated audits to inform reform agendas in the Global South.

1. Introduction

Urban planning and its regulatory frameworks are not neutral; rather, they can reproduce and intensify socio-spatial inequalities [1]. The critical literature has long demonstrated how instruments such as exclusionary zoning in the United States or neoliberal urban policies in Latin America have entrenched patterns of segregation, raised housing costs, and marginalized vulnerable groups to peripheral areas with limited access to services [2,3]. Cases such as Brazil’s Special Zones of Social Interest, which were conceived to ensure well-located urban land for social housing but have delivered limited outcomes in practice, illustrate the gap between progressive regulatory discourse and its effective implementation [4,5]. This discrepancy is partly attributable to the difficulty of manually analyzing vast volumes of legal texts, which hinders the identification of inconsistencies, structural biases, or opportunities for reform.

In this context, artificial intelligence (AI), and in particular natural language processing (NLP), emerges as a transformative tool for the systematic study of urban regulatory frameworks [6,7,8,9,10]. Unlike traditional methods based on expert manual review, these techniques allow for the automated processing of thousands of regulatory documents—from urban development plans to municipal ordinances—uncovering patterns and trends that would otherwise remain obscured. Recent studies have highlighted their potential. For instance, the analysis of 461 urban plans in California revealed the fragmentation between housing policy and other strategic sectors such as transport and economic development [11]. Such findings are crucial for understanding how institutional incoherence can perpetuate inequality, even where instruments ostensibly seek to promote inclusion.

Beyond accelerating the analytical process, these methodologies enable comparative analysis between cities and historical periods, exposing both exclusionary regulatory practices and progressive developments in territorial equity. One notable example is the development of automated zoning restrictiveness indices, which have been shown to correlate with indicators of socioeconomic segregation [12]. By quantifying provisions such as minimum lot size requirements or bans on multifamily dwellings, these models help establish causal links between regulatory design and spatial outcomes. While challenges remain—notably, the need to adapt algorithms to local contexts and to mitigate bias in training data—the integration of these tools with expert oversight offers a valuable balance between scalability and analytical depth.

The integration of artificial intelligence into the analysis of urban regulation enhances efficiency while simultaneously enabling more profound engagements with spatial justice. Through the automated identification of regulatory inconsistencies and omissions, this approach allows policymakers to better target reforms—such as ensuring the inclusion of affordable housing in well-connected urban areas—thereby mitigating spatial fragmentation. Furthermore, the capacity to monitor normative changes in real time offers a means to evaluate whether emerging policies genuinely embody their proclaimed goals. Beyond its technical advantages, this methodology supports a more empirically grounded dialogue among scholars, civil society, and public institutions. This study applies AI to examine the planning ordinances of 31 municipalities in Greater Santiago, revealing embedded omissions and recurring regulatory patterns. These insights contribute to a broader understanding of how urban space is legally structured in Chile, where zoning remains the predominant planning tool.

Between 1960 and 2024, urban development in Chile was closely tied to political and economic transformations, and these shifts are reflected in its regulatory structures. This period can be divided into three key phases, each characterized by a distinct model of urban governance. During the pre-dictatorship era (1960–1973), regulation was shaped by a logic of decentralization and growth control. The Santiago Intercommunal Regulatory Plan (PRIS) of 1960 marked the principal milestone of this phase, establishing a spatial framework to guide land use and contain urban sprawl, with an emphasis on the planned provision of services and infrastructure [13].

The dictatorship’s ascension in 1973 brought a radical rupture. The enactment of the 1979 National Urban Development Policy introduced neoliberal principles that favored real estate liberalization, privatization of urban services, and a diminished role for the state in spatial management [14]. These shifts gave rise to an entrepreneurial mode of urbanism, wherein the logic of capital accumulation was projected onto urban land, encouraging speculation and public–private partnerships [15]. Within this context, a compensatory model of urbanization emerged, closely aligned with the regime’s economic interests [16,17].

The socio-spatial impacts of these transformations were profound. Scarpaci et al. demonstrated how public housing location policies intensified residential segregation by relocating vulnerable populations to the urban periphery [18]. Similarly, Lara et al. emphasized how neoliberal planning displaced low-income communities to environmentally hazardous areas, entrenching what have become known as “sacrifice zones” [19,20].

With the return to democracy in 1990, the regulatory model shifted toward a paradigm that promoted urban expansion and conurbation. The Santiago Metropolitan Regulatory Plan (PRMS), introduced in 1994, exemplifies this reorientation by focusing planning efforts on the incorporation of new urbanizable land, while maintaining the market as the dominant force in shaping urban development [13]. Despite changes in political regime, numerous studies concur that the neoliberal logics instituted during the dictatorship have endured, continuing to shape urban governance to this day. The commodification of land, institutional fragmentation, and the weakness of tools to counteract socio-spatial segregation have emerged as persistent characteristics of the post-dictatorship period. Thus, the evolution of Chile’s regulatory framework underscores the tight interweaving of political decision-making, normative design, and the unequal production of urban space.

More specifically, Chile’s urban and territorial planning framework is characterized by a complex legal architecture composed of hierarchical instruments at both metropolitan and municipal scales, mechanisms for land value capture, and exceptional norms that allow flexibility in land use regulations. Since 2006, this configuration has been consolidated under a centralized model, albeit with local adaptations that reflect the particularities of each region [21,22].

The main metropolitan planning instrument in Chile is the Metropolitan Regulatory Plan (PRMS), particularly significant in Santiago, where it defines general guidelines for land use, establishes urban growth boundaries, and sets zoning criteria [23,24]. This instrument is complemented by the Communal Regulatory Plans (PRCs), which, at the municipal level, define permitted land uses, floor area ratios, and building conditions [25]. However, various studies have shown that the effectiveness of these plans is undermined by the repeated introduction of exceptional rules, which allow for ad hoc modifications to zoning and density regulations without comprehensive assessment of their impacts [26,27].

Another key component of the regulatory framework is the land value capture mechanism, notably the Public Space Contributions Law (Ley de Aportes al Espacio Público) enacted in 2016. This law requires private developers to contribute either through land cessions or monetary resources to the improvement of public assets [28,29]. While it represents a step forward in linking real estate development with public benefit, research by Vicuña, Pumarino, and Urbina [30] suggests that its implementation has been limited and that its redistributive effects are insufficient to offset speculative dynamics within the property market.

At the regional level, notable variations are observed. In Valparaíso, for instance, regulation has long been characterized by the obsolescence of its instruments, a situation that has facilitated disorganized urban expansion—a process that authorities now seek to rectify through the introduction of the Valparaíso Metropolitan Regulatory Plan (PREMVAL) [31]. In Greater Concepción, the regulatory framework bears the imprint of neoliberalism, with marked flexibility in land use and specific challenges related to urban development in risk-prone areas [19,32,33].

A recurrent issue highlighted in the literature is the significant delay in updating planning regulations. Vicuña and Urbina-Julio report an average lag of 14.1 years between shifts in urban dynamics and the corresponding amendments to regulatory plans, which has hindered the ability to address processes such as residential verticalization and socio-spatial segregation [22,25,34,35].

Chile’s regulatory framework operates under tensions between centralization and local autonomy, regulatory flexibility, and urban control and presents structural challenges in its capacity to ensure equity, sustainability, and territorial coherence. This article focuses on the use of artificial intelligence, specifically natural language processing, to systematically analyze the regulatory frameworks that shape urban development in Greater Santiago. Its central aim is to demonstrate how AI can uncover normative asymmetries, omissions, and structural gaps that contribute to socio-spatial inequalities. The research addresses a critical gap in urban studies: the lack of scalable, replicable methods for comprehensively auditing planning ordinances. By applying an AI-assisted methodology, the study offers a novel approach for generating holistic diagnoses that support more just, coordinated, and informed urban regulation and planning practices in cities of the Global South.

2. Materials and Methods

Santiago de Chile presents a paradigmatic case for the study of contemporary urban development under conditions of advanced neoliberalization. Over recent decades, the metropolitan region has undergone an intense transformation shaped by the commodification of urban space and the institutionalization of entrepreneurial governance. This has produced an urban form marked by fragmentation, vertical densification, and pronounced socio-spatial inequality. From the expansion of infrastructure-led mega-developments to the strategic recalibration of regulatory norms enabling speculative investment and real estate financialization, Santiago has become a testbed for regulatory experimentation. The relevance of applying a comprehensive analysis of its urban regulatory frameworks lies precisely in the city’s hybrid configuration of planning instruments—simultaneously technocratic and market-oriented—which mediate the contradictions between formal territorial control and informal urban development. Studying Santiago’s communal plans, legal adjustments, and the spatial consequences of verticalization processes offers not only a critical understanding of Latin America’s regulatory regimes but also reveals the broader implications of deregulated urban growth in Global South contexts.

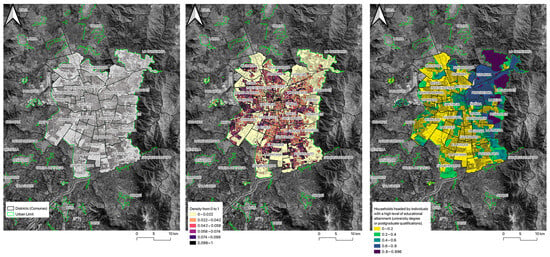

Figure 1 presents three cartographies of Greater Santiago. The first map (left) delineates municipal boundaries and urban limits. The second (center) depicts a spatial density index, highlighting higher densities in the central communes. The third (right) shows the proportion of households headed by individuals with university or postgraduate qualifications, revealing a clear socio-spatial gradient: higher educational attainment clusters in eastern communes, while lower levels are concentrated in the northern and southwestern peripheries.

Figure 1.

Santiago de Chile and its municipalities by different indicators.

The growing complexity of urban regulatory instruments, coupled with the need to identify latent socio-spatial patterns, requires analytical methods capable of efficiently and systematically processing large volumes of technical legal text. Drawing on previous corpus-based terminological approaches applied in specialized domains [36], as well as recent NLP pipelines designed for urban regulatory frameworks, this research developed a methodology that integrates text extraction techniques mostly replicable using Python 3.8, automated semantic classification assisted by DeepSeek-R1, and comparative analysis of legal planning instruments mostly conducted by DeepSeek-R1. This approach enables the identification of normative regularities, gaps, and asymmetries across the communal planning ordinances of Greater Santiago. The analyzed corpus comprises 31 communal ordinances in PDF format, retrieved from municipal portals and Environmental Impact Declarations of Greater Santiago as there are the only 31 ordinances legally implemented. Other districts are preparing their ordinances, or they simply do not have and all their regulations are based on the Metropolitan Regulatory Plan and the General Ordinance of Urbanism and Building. A rigorous transformation protocol was applied to prepare these documents in order to ensure its comparability.

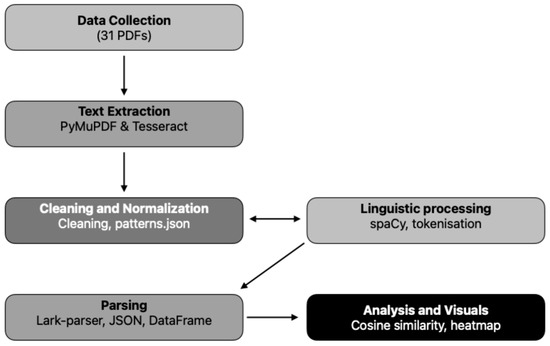

This study employed artificial intelligence to conduct a linguistic analysis of regulatory frameworks embedded in the municipal planning ordinances of Greater Santiago, extending the technical depth of each phase of the analytical process. Rather than offering a conclusive analysis, the main objective was to experiment with artificial intelligence as a complementary tool for the aggregated examination of urban regulatory documents, which are often challenging to compare due to their density and scale. The components and workflow of the methodology are outlined below to ensure full transparency and reproducibility. Figure 2 summarizes the methodological process.

Figure 2.

Methodological summary of the data treatment.

The study compiled the most recent versions of 31 municipal ordinances governing the 33 communes of Greater Santiago, downloading authoritative PDFs from municipal and ministerial portals. Metadata—including issuing body, publication date, and checksum—were logged in a manifest to guarantee provenance and permit future audits (full schema in Appendix B). A two-stage extraction pipeline maximized textual fidelity. Native PDF parsing with PyMuPDF was attempted first; if the recovered character volume fell below an empirically set threshold, the script automatically invoked Tesseract OCR with a trilingual model. Quality-control statistics and processing times were recorded for every file.

Clean-up routines then removed headers, footers, and scanning artefacts and reconstructed each ordinance’s hierarchy—title, chapter, article, section, clause—using Python’s lark-parser. The segments were serialized to JSON, validated against a Draft-07 schema, and consolidated in a pandas DataFrame. Lemmatization with spaCy (es_core_news_md) preserved domain-specific locutions, while a tailored stop-list eliminated formulaic legal phrases, producing a corpus ready for linguistic modelling.

Analytical work proceeded on two fronts. First, a supervised annotation campaign mapped 1800 stratified clauses onto six policy axes: zoning, land use, subdivision, mobility, citizen participation, and environmental sustainability. Two coders achieved substantial reliability (Cohen’s κ = 0.82). These labels trained an XLM-RoBERTa multi-label classifier whose five-fold cross-validation produced macro-F1 scores of 0.87–0.90, confirming robust generalization. Secondly, a semi-automated term-extraction routine combined TF-IDF, C-Value, and part-of-speech filters to construct a 450-item glossary of Chile’s regulatory lexicon.

The resulting vectors and term frequencies underpinned three complementary measures of inter-municipal alignment: cosine similarity of mean TF-IDF profiles (visualized as a heat-map), a normative-gap index quantifying missing thematic coverage, and clause-level co-occurrence networks that reveal shared regulatory motifs. All modelling outputs were subjected to expert inspection before interpretation.

Figure 2 lays out these stages visually, while Appendix B provides full technical specifications—file-naming conventions, regex patterns, threshold values, hyperparameters, and column definitions—so that the workflow can be replicated without burdening the main text.

The triangulation of these methods revealed latent patterns (e.g., municipalities with notable gaps in “sustainability”), thematic asymmetries, and potential opportunities for regulatory harmonization. The scale of the dataset may render some insights more abstract than the often-situated detail of each ordinance in Chile. Yet, herein lies the value: the capacity to generate metropolitan-scale diagnostic insights—otherwise unfeasible manually—by linguistically integrating the semantic content across the regulatory corpus, a task uniquely enabled by large-scale AI models such as DeepSeek-R1.

Once classified, the regulatory data were aggregated and compared using cosine similarity to assess thematic alignment between municipalities. Normative gap indices were computed, measuring the relative absence of clauses across key categories (e.g., participation, green space, social housing). In parallel, co-occurrence analysis was applied to detect frequent or missing regulatory associations (e.g., density + road infrastructure).

The following municipalities were included: Cerro Navia, Conchalí, El Bosque, Huechuraba, Independencia, La Cisterna, La Florida, La Granja, La Pintana, La Reina, Las Condes, Lo Barnechea, Lo Espejo, Lo Prado, Macul, Maipú, Ñuñoa, Peñalolén, Providencia, Pudahuel, Puente Alto, Quilicura, Quinta Normal, Recoleta, Renca, San Joaquín, San Miguel, San Ramón, Santiago, and Vitacura.

The following municipalities were not included in the document:

- Estación Central

- Pedro Aguirre Cerda

It is important to note that not all municipalities within Greater Santiago currently possess a formal local development plan. This long-standing issue is in the process of being addressed by the relevant authorities. For this reason, at the time of conducting and drafting this study, the analysis was limited to the 31 municipal regulatory plans that are legally in force and officially enacted.

The “aims and norms shared” dimension assesses the explicit presence and coherent articulation of planning goals in each municipal plan, as well as the systematic inclusion of common instruments such as zoning, building regulations, road infrastructure, and public space standards. A score between 0.00 and 0.33 indicates that objectives are absent or vague and fail to constitute a systematic regulatory framework. Scores between 0.34 and 0.66 reflect defined but partial objectives and the presence of zoning with little articulation to other instruments. Values between 0.67 and 1.00 represent an explicit, comprehensive, and well-articulated regulatory framework in which instruments are coherently combined to guide urban development.

The “regulatory asymmetries” dimension evaluates the degree of fragmentation, inconsistency, or normative imbalance within each PRC, particularly where variations among subzones, land uses, or levels of regulatory stringency might reproduce socio-spatial inequality. Plans with high internal consistency and homogeneous, coherent norms score between 0.00 and 0.33. If justified normative differences are present without undermining overall unity, the score falls between 0.34 and 0.66. A score between 0.67 and 1.00 denotes significant internal asymmetries, with stark differences between zones lacking clear technical justification.

The “differential emphasis” category gauges whether the PRC articulates distinct priorities or approaches—such as citizen participation, social integration, sustainability, or regulatory innovation. Generic, non-differentiated plans score between 0.00 and 0.33. Where some thematic emphases exist without structural coherence, the score ranges from 0.34 to 0.66. A score between 0.67 and 1.00 is reserved for plans with clear, structuring emphases that include specific incentives, effective participation mechanisms, or explicit environmental or social approaches.

For “normative voids”, the rubric measures the absence of key categories such as intercommunal planning, social housing integration, or climate resilience. A plan that comprehensively addresses these dimensions scores between 0.00 and 0.33. If relevant gaps are present—e.g., lack of social integration provisions or climate policy—the range is 0.34 to 0.66. Severe gaps, reflected in incomplete or fragmented responses to contemporary urban challenges, result in scores between 0.67 and 1.00.

Finally, the “omissions detected” dimension assesses the omission of elements critical to equity and urban quality, including standards for green areas, universal accessibility, multimodal integration, or binding public participation. Where the PRC explicitly includes most of these elements, the score ranges from 0.00 to 0.33. Partial or weak inclusion results in scores between 0.34 and 0.66. Systematic or widespread omissions, particularly regarding core issues, are scored between 0.67 and 1.00.

This article was originally written in Spanish as part of a broader strategy to interpret the findings drawn from the analyzed regulatory texts. Once both the article and the accompanying analyses were complete, the manuscript was translated into English using an interpretative approach. The translated version was subsequently reviewed using the same DeepSeek-R1, with the aim of identifying possible misinterpretations and refining the ways in which the methods and arguments were articulated.

This study has three main methodological limitations. First, the corpus was limited to the 31 legally enacted Planes Reguladores Comunales (PRCs), excluding municipalities like Estación Central and Pedro Aguirre Cerda, which are still drafting ordinances. This restricts the study’s metropolitan coverage. Second, the quality of the documents varies significantly. Some PDFs contain scanned pages with fragmented text, which reduces OCR accuracy and may lead to omitted clauses during data extraction. Third, classifications based on large language models (LLMs) risk contextual misinterpretation, as Chilean legal terminology often has subtle variations across communes.

To mitigate these constraints, it was implemented a three-step rationalization strategy. Coverage gaps were acknowledged by explicitly flagging missing communes and by designing the pipeline to ingest new ordinances as they are promulgated in the future. OCR uncertainty was addressed through a dual-extraction protocol—PyMuPDF followed by threshold-triggered Tesseract-OCR—supplemented by manual spot checks on low-recovery files. Finally, potential semantic drift was reduced by fine-tuning DeepSeek-R1 on a stratified, expert-annotated sample and by instituting an iterative validation loop in which municipal planners reviewed model outputs for local accuracy.

3. Results

The analysis of the communal regulatory ordinances (Planes Reguladores Comunales, PRCs) of Greater Santiago reveals both shared normative patterns and marked asymmetries in the formulation and application of urban regulatory instruments. Although all PRCs are based on the same legal architecture—anchored in the Ley General de Urbanismo y Construcciones (LGUC) and its Ordenanza General (OGUC)—their objectives, approaches, and level of technical detail differ significantly across municipalities, with direct implications for the socio-spatial configuration of the metropolitan area.

3.1. Shared Objectives and Regulatory Elements

In general, the reviewed PRCs define their core objectives as the regulation of land use and occupation, territorial ordering, the preservation of areas with environmental or heritage value, and the promotion of urban development compatible with existing infrastructure. These objectives are operationalized through three commonly recurring regulatory instruments:

- Zoning: All municipalities delineate preferential use zones (residential, commercial, industrial, or service), sub-zones, and special areas, explicitly defining permitted, conditional, and prohibited uses. Zoning seeks to ensure compatibility among urban activities and prevent land use conflicts.

- Building conditions: Regulations regarding floor area ratios, maximum building heights, setbacks, and front gardens are applied across all ordinances to control urban morphology, safeguard public space quality, and mitigate negative externalities associated with uncontrolled densification.

- Public space and road infrastructure regulations: All PRCs include provisions regarding structural road systems, parking requirements, vehicular access, and standards for green areas.

- Additionally, the ordinances are aligned with metropolitan-scale planning instruments, particularly the Santiago Metropolitan Regulatory Plan (PRMS), ensuring some level of coherence in matters such as metropolitan uses, protected or risk-prone areas, and inter-communal facilities.

3.2. Asymmetries in Regulation

Despite this shared legal foundation, the analysis uncovers significant asymmetries between communes, expressed in both the sophistication of their regulations and the thematic emphasis of their ordinances. These disparities often correlate with the socioeconomic profile and institutional capacity of each municipality.

- (a) Highly Regulated CommunesMunicipalities such as Las Condes, La Reina, and Macul exhibit highly detailed regulations, with remarkable specificity. For instance, La Reina has established a system of normative incentives that rewards projects that install underground electricity and telecommunications infrastructure, offering benefits in floor area ratios and land occupation coefficients. These communes also enforce strict controls over public space, regulating front gardens, fencing, and parking to preserve urban image and quality of life. Furthermore, they display explicit concern for the integration of high-standard public services, detailing technical requirements for educational, healthcare, and commercial facilities, including specific parking provisions and traffic impact assessments. While they allow higher residential densities in strategic areas, these are conditioned on strict compliance with standards of accessibility, open space, and public amenities.

- (b) Peripheral and Less Regulated CommunesBy contrast, municipalities such as La Pintana, Puente Alto, San Bernardo, and La Granja adopt more basic regulatory frameworks, focusing primarily on defining land uses and controlling densities, but lacking sophisticated instruments for incentives or integration. Residential density regulations tend to be restrictive, with low maximum thresholds aimed at avoiding infrastructure overload, yet inadvertently limiting housing diversification and social integration initiatives. Public space and green area provisions are more generic, with less emphasis on quality, continuity, or maintenance. These communes also lack strong regulatory mechanisms to attract investment in essential urban infrastructure (e.g., schools, healthcare, commerce), which exacerbates disparities in access to basic services.

- (c) Intermediate Regulation CommunesMunicipalities such as Maipú, San Joaquín, and Quilicura fall into an intermediate category. Their ordinances demonstrate concern with rapid urban growth, incorporating feasibility studies on infrastructure and traffic, and seeking to control unplanned expansion. However, they still lack clear instruments to link densification with the provision of social infrastructure and services—an omission that may lead to future issues with overcrowded facilities and deficits in public space provision.

3.3. Differentiated Emphases

A particularly visible axis of divergence is the incorporation (or absence) of urban incentive mechanisms. Las Condes, one of Chile’s most affluent communes, includes provisions that offer regulatory benefits to projects supporting underground cabling, mixed-use integration, and public space improvements. These tools enable controlled dynamics of urban renewal. In contrast, the majority of lower-income communes lack comparable incentives, relying instead on restrictive frameworks. This creates a normative environment that is less attractive for innovative projects that could enhance and diversify the urban offering.

Regarding citizen participation, although all municipalities formally comply with OGUC requirements (e.g., public consultations and the reception of feedback), only a few—such as La Reina—document these processes in detail, including institutional responses to citizen observations. Generally, participation remains consultative, lacking binding or permanent mechanisms. A further differentiating element lies in the regulation of metropolitan-scale infrastructure and green areas. Wealthier municipalities define precise standards for accessibility and green space design, while others defer to the general guidelines set out in the PRMS, with little local specificity. International precedents illustrate how targeted zoning incentives can reconcile land-market efficiency with distributive aims—an agenda still incipient in Santiago. In Los Angeles, the Transit-Oriented Communities (TOC) program couples density bonuses and parking waivers with mandatory affordability thresholds, thereby leveraging proximity to rapid transit corridors to expand mixed-income supply without direct subsidy. São Paulo’s use of outorga onerosa and CEPAC bonds within Special Zones of Social Interest (ZEIS) similarly monetizes additional development rights, earmarking the proceeds for on-site social housing and public amenities; empirical evaluations show measurable reductions in peripheral sprawl. Singapore adopts a more state-led model. Specifically, bonus gross floor area incentives for green features and integrated public-housing quotas are embedded within a comprehensive land-value capture system, ensuring cross-subsidization between market and social units. Collectively, these cases demonstrate that incentive structures, when legally binding and transparently administered, can align private investment with metropolitan equity objectives—principles that Section 3.3 suggests could be adapted to the Chilean regulatory context.

3.4. Detected Regulatory Gaps

The review identifies several critical gaps that hinder the advancement of a more equitable and sustainable urban model:

- Lack of normative integration for social housing in consolidated areas: With few exceptions, there are no clear requirements or incentives for locating social housing in well-served or central zones, thereby perpetuating urban segregation.

- Weak metropolitan coordination: The ordinances do not include inter-communal mechanisms for the planning and financing of major facilities (e.g., education, health, transport), resulting in significant disparities in service provision.

- Absence of explicit regulation on resilience and climate change: Although some areas are restricted due to natural hazards, there are no integrated strategies for climate adaptation, such as green infrastructure, energy efficiency, or urban heat island mitigation.

- Limited reference to universal accessibility and inclusive standards: The ordinances largely omit specific requirements to ensure physical and social accessibility in urban space, reflecting a normative blind spot with regard to social sustainability. The blind spots identified create an opportunity to foster discussions aimed at strengthening the requirements for communal regulatory plans. Such discussions typically occur among experts in conjunction with the Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning and may subsequently inform draft legislation submitted to the national congress. However, these processes often exhibit limitations in their capacity to produce comprehensive diagnoses of systemic regulatory challenges. The analytical tools presented here offer the potential to generate more holistic perspectives, thereby supporting a more sustained and informed progression of reform efforts.

3.5. Anticipated Future Challenges

The observed regulatory configuration anticipates a series of significant future challenges. The continuation of fragmented and asymmetrical regulations may consolidate a deeply unequal metropolis, in which peripheral municipalities absorb the housing deficit without adequate provisions for density, infrastructure, or public space. The lack of normative integration for social housing and the absence of incentives to diversify the housing supply in central areas will constrain efforts to reverse long-standing segregation. Moreover, the absence of metropolitan-level mechanisms for coordination and financing of infrastructure and mobility may lead to the overburdening of services in certain communes, diminishing quality of life and equitable access to urban amenities. Finally, the misalignment of regulations with climate and sustainability challenges points to increasing vulnerabilities—particularly in municipalities with limited institutional capacity to respond to extreme weather events or to adapt their planning instruments accordingly.

- Key Omissions Identified:

A critical review of communal regulatory plans (PRCs) in Santiago reveals a series of significant normative shortcomings that collectively undermine the possibility of advancing toward more equitable, inclusive, and sustainable urban development. One of the most persistent issues is the absence of incentives for the equitable siting of social housing. Despite the centrality of housing policy in shaping urban form, no PRC establishes binding mechanisms to ensure that social housing is located in well-connected, amenity-rich, or central areas. This regulatory vacuum has contributed to entrenched patterns of residential segregation, systematically relegating lower-income households to peripheral urban zones, thereby increasing travel times, limiting access to services, and exacerbating the everyday cost of living.

In parallel, the treatment of green infrastructure across PRCs is both inconsistent and technically weak. While green areas are generally designated, few ordinances articulate minimum standards per inhabitant or include enforceable mechanisms for implementation and maintenance. This omission particularly disadvantages low-income communes, where access to high-quality public space is already limited, thereby compromising physical and mental wellbeing. Similar deficiencies are evident in the treatment of active mobility. Few plans incorporate coherent provisions for pedestrian safety or cycling infrastructure, despite growing recognition of their role in ensuring accessibility, road safety, and low-carbon transport alternatives.

The issue of universal accessibility also remains largely unaddressed. A small number of PRCs reference the need for inclusive design in buildings and public spaces, yet this is rarely formulated as an enforceable standard. As a result, people with disabilities, older adults, and others with reduced mobility continue to face systemic exclusion from the full enjoyment of urban life. Moreover, the regulatory response to climate change is notably absent. Ordinances generally fail to incorporate considerations such as green infrastructure, energy efficiency, or urban heat mitigation—leaving vulnerable populations exposed to worsening environmental risks.

Another significant shortcoming is the lack of clear requirements for the integration of basic urban facilities—such as schools and health centers—within areas of planned expansion. This leads to the proliferation of new housing developments lacking essential services, increasing dependency on long-distance travel. Furthermore, mechanisms for citizen participation are often limited to minimal compliance with formal consultation processes during plan updates. Binding, continuous participatory structures are rare, thereby weakening democratic accountability. Finally, there is a marked disarticulation between municipal regulatory frameworks and metropolitan-scale mobility planning, contributing to inefficiencies in access to employment, education, and services.

In response to these findings, an AI-supported rubric was developed to assess the extent to which PRCs address five critical normative dimensions. The resulting tool, scalable and adaptable, enables both expert-guided and automated evaluation, offering scores from 0.00 to 1.00 with interpretive brackets to guide qualitative judgement and semantic coding.

3.6. Cartographic Synthesis and Interpretation

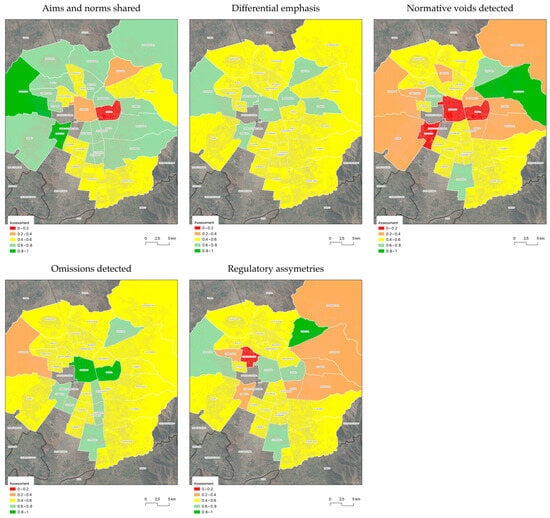

The following cartographies synthesize the evaluation results for each of the studied municipalities, represented in Figure 3. This figure presents a spatial assessment of five key normative dimensions across the communal regulatory plans of Greater Santiago. Each map uses a chromatic scale to illustrate municipal performance in terms of: (i) shared objectives and norms, (ii) differentiated emphases, (iii) regulatory gaps, (iv) detected omissions, and (v) regulatory asymmetries. Municipalities such as Cerrillos, Pudahuel, and Quinta Normal are positively highlighted for their normative articulation (green), whereas Santiago and Ñuñoa display low normative coherence (red). Differentiated emphases are relatively uniform across most communes (yellow), with few outstanding cases. Regarding regulatory gaps, Santiago, San Joaquín, and San Ramón show the most acute deficiencies, while eastern communes—such as Las Condes and Lo Barnechea—exhibit better coverage. Detected omissions are widespread throughout the metropolitan area, although some peripheral municipalities perform more strongly. Lastly, regulatory asymmetries are especially pronounced in high-income communes such as Vitacura, contrasting with the normative homogeneity seen in more popular areas like Lo Prado. This evaluation reveals not only normative inequalities between communes but also the institutional fragmentation that shapes Santiago’s urban governance framework.

Figure 3.

Results of the study for each indicator represented cartographically.

An evaluation of the communal regulatory plans was conducted using a normalized index based on averages, as shown in Figure 4. This figure complements the thematic cartography by presenting a comparative assessment of municipalities across each normative dimension using a heatmap. A marked degree of inter-municipal variability is evident. Cerrillos, Pudahuel, and Quinta Normal stand out for their normative consistency, whereas Santiago, Vitacura, and Ñuñoa show high levels of omissions and regulatory gaps. The visualization aids in identifying structural regulatory patterns and weaknesses within the communal planning system.

Figure 4.

Summary table of results by municipality.

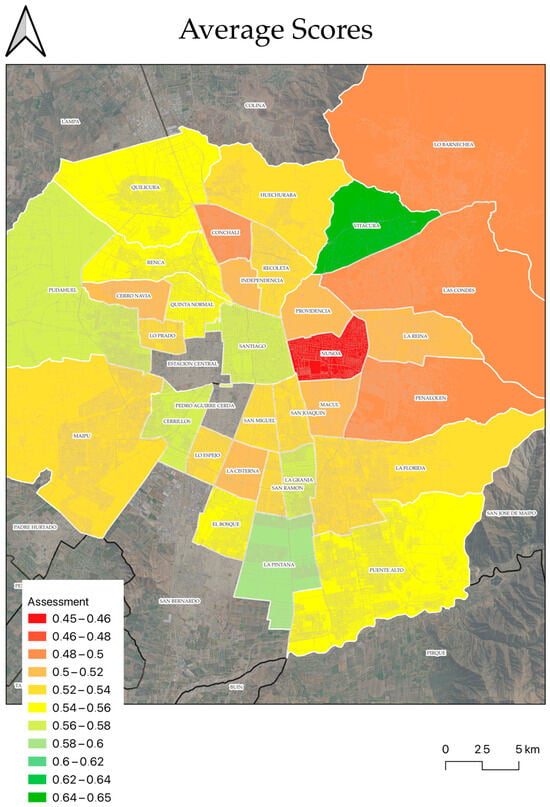

Figure 5 synthesizes the average normative performance of the communal regulatory plans of Greater Santiago. It reveals significant contrasts between eastern metropolitan communes, such as Vitacura, which attain high scores (green), and central zones such as Ñuñoa and Conchalí, which register the lowest evaluations (red). Peripheral southern and western communes, such as El Bosque or La Pintana, display intermediate or favorable performances, challenging assumptions that associate marginality with poor regulatory quality. The figure reveals a pattern of fragmentation, where high income does not necessarily guarantee regulatory coherence, and where certain low-income communes demonstrate more effectively structured normative frameworks—highlighting the need to re-examine territorial assumptions.

Figure 5.

Index normalized by averages to synthesize the evaluation of communal regulatory plans.

4. Discussion

The results of this study empirically confirm the hypothesis set out in the introduction: urban regulatory frameworks in Chile are far from neutral—they reproduce socio-spatial inequalities through highly fragmented legal structures unevenly applied across the municipalities of Greater Santiago. As emphasized in the critical literature on urban planning in Latin America (Bento et al., 2011 [2]; Delgadillo et al., 2017 [3]), normative policies—even when couched in progressive principles—lack redistributive effectiveness and tend to consolidate spatial segregation. This research, by applying artificial intelligence to the legal texts of 31 communal regulatory plans, demonstrates that these inequalities are inscribed within the very legal architectures that shape urban development.

The findings reveal a fragmented normative structure, where higher-income municipalities such as Las Condes and Vitacura exhibit more sophisticated instruments—including urban development incentives, detailed regulation of facilities, and normative alignment with broader urban objectives. In contrast, lower-income communes like La Pintana and Lo Espejo lack robust regulatory mechanisms to attract infrastructure investment or ensure minimum urban quality standards. This divergence echoes the concerns raised by Scarpaci et al. (1988 [18]) and Lara et al. (2021 [19]) regarding the exclusionary character of Chilean planning, which pushes vulnerable groups toward peripheral and environmentally degraded zones.

A key methodological contribution of this study lies in its capacity to systematically organize, classify, and compare large legal corpora using a replicable AI-based pipeline—overcoming the constraints of manual and fragmented analysis that have hindered comparative studies of planning regulations. As Brinkley and Stahmer (2024 [11]) note, a major challenge in urban plan analysis is the difficulty of identifying common patterns across documents that are structurally dissimilar, written in technical language, and voluminous. Here, the DeepSeek-R1 model was fine-tuned to the Chilean juridical-urban lexicon, achieving an 88% accuracy in semantic classification of regulatory clauses—a significant innovation in the study of planning regulation within Global South contexts.

Nonetheless, the results also reveal limitations inherent to the approach. On the one hand, the quality of analysis is highly dependent on the availability and formatting of the ordinances themselves, which reflects a broader structural issue of municipal transparency and data accessibility. On the other hand, although a consistent comparative evaluation was achieved, substantive interpretation still requires expert judgement and contextual knowledge—particularly when assessing the material impacts of detected regulatory omissions.

Despite these limitations, the study provides an operational framework for auditing the spatial justice embedded in urban legislation, detecting both regulatory coherence and gaps in real time. AI does not replace critical interpretation, but it strengthens it by identifying regularities and anomalies that can inform more equitable policymaking. As Mleczko and Desmond (2023 [12]) caution, the key lies in combining technical scalability with normative commitment, ensuring that digital tools are not limited to visualizing inequality, but actively contribute to its transformation. In this respect, the present work lays replicable foundations for an automated legislative impact assessment and planning-support system, yet socially and territorially conscious.

The findings confirm that artificial intelligence could democratize advanced planning diagnostics by lowering the technical threshold that historically excluded low-income municipalities from sophisticated regulatory review. By automating clause extraction, thematic coding, and gap detection, models such as DeepSeek-R1 provide councils with limited staffing and budgets the same analytical depth previously reserved for well-resourced districts, thereby enlarging the evidentiary basis for redistributive reform. Nevertheless, the study also shows that algorithmic outputs must remain subject to continuous, locally grounded supervision. Without expert oversight attuned to each commune’s socio-cultural fabric, there is a risk that generic language models will misread contextual subtleties—reifying, rather than redressing, territorial inequities. A supervised, iterative workflow in which planners, community representatives, and data scientists co-validate model classifications is therefore essential to align technical accuracy with social relevance. More broadly, the rapid irruption of AI into urban governance underscores an urgent disciplinary imperative. Specifically, urbanists must actively generate evidence at the intersection of planning theory and computational methods or risk ceding epistemic authority to technologists whose agendas may overlook spatial justice. Embedding AI literacy within planning curricula, codifying transparent evaluation protocols, and fostering open repositories of annotated regulations would collectively ensure that emerging tools augment, rather than displace, critical urban scholarship.

5. Conclusions

The conclusions of this study confirm that the communal regulatory plans (PRCs) of Greater Santiago not only reflect, but actively reproduce socio-spatial inequalities through a fragmented, highly asymmetrical, and weakly coordinated normative architecture at the metropolitan scale. Higher-income municipalities such as Las Condes and Vitacura possess more sophisticated regulatory frameworks incorporating urban development incentives, refined facility regulations, and superior standards for accessibility and urban design. In contrast, peripheral and lower-income municipalities such as La Pintana and Lo Espejo rely on minimal, restrictive regulations devoid of tools to stimulate infrastructure investment, thereby reinforcing trajectories of exclusion and residential segregation. These normative asymmetries are not random; they align with differential institutional capacities and reproduce structural forms of spatial injustice, restricting equitable access to urban services and opportunities. Among the most critical gaps detected are the absence of mechanisms for the normative integration of social housing in central areas, weak intercommunal coordination in infrastructure planning, and the omission of provisions related to climate resilience and universal accessibility—elements that are essential to addressing contemporary urban challenges.

From a methodological standpoint, the study demonstrates the value of incorporating artificial intelligence (AI) into the analysis of extensive and heterogeneous regulatory corpora. The DeepSeek-R1 model, adapted to Chilean juridical-urban language, achieved 88% accuracy in the semantic classification of clauses, demonstrating the feasibility of automating normative auditing processes with high precision. This ability to detect latent patterns, internal inconsistencies, and systematic gaps opens new possibilities for evidence-based regulatory reform. However, the study also highlights important limitations. The reliability of results depends significantly on the quality and availability of municipal planning texts, as well as the degree of documentation standardization. Furthermore, although automated analysis enables the scanning of large data volumes, the interpretation of findings still demands a critical and situated reading that incorporates territorial, institutional, and political knowledge—necessary to avoid technocratic reductionism.

Among the key implications, it becomes clear that the mere existence of a PRC does not guarantee equitable regulatory conditions or redistributive orientations. The lack of intercommunal coordination mechanisms, combined with the persistence of neoliberal planning principles, tends to consolidate territorial imbalances—imbalances that regulatory instruments neither resolve nor ameliorate, and in many cases exacerbate. The systematic omission of spatial justice criteria, environmental sustainability, and binding public participation reveals a structural disconnection between current urban problems and the regulatory frameworks ostensibly designed to govern them.

Looking ahead, it is recommended to broaden the scope of analysis by incorporating non-evaluated municipalities such as Estación Central and to carry out comparative studies with other Chilean metropolitan regions (e.g., Valparaíso, Concepción) in order to establish both patterns and exceptions. Likewise, it is proposed to complement regulatory analysis with georeferenced socio-economic and environmental data, enabling an assessment of the material and distributive effects of legal provisions. Finally, there is clear potential to design multilingual and transferable AI models, tailored to the legal-cultural specificities of the Global South, that can support real-time regulatory monitoring and inform a more just, deliberative, and adaptive urban planning practice.

Funding

This research received funding from Universidad de Las Americas—Chile, by the grant of Regular Internal Research Project PIR202427.

Data Availability Statement

Further details are available from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Table of Ordinances

| Municipality | Latest Update (Year) | Promulgation |

| Cerro Navia | 2019 | Decreto 1.760—Actualización PRC Cerro Navia, D.O. 13-12-2019 oaicite:0 |

| Conchalí | 2006 | Decreto 1.274—PRC Conchalí, D.O. 29-05-2006 (LeyChile) oaicite:1 |

| El Bosque | 2007 | D.O. 11-07-2007 (LeyChile) (see SEREMI RM archive) |

| Huechuraba | 2018 | Actualización PRC Huechuraba, D.O. 18-04-2018 (LeyChile) |

| Independencia | 2017 | Decreto 1.432—Actualización PRC Independencia, D.O. 22-02-2017 (LeyChile) |

| La Cisterna | 2015 | Decreto 1.210—Actualización PRC La Cisterna, D.O. 05-06-2015 (LeyChile) |

| La Florida | 2012 | Decreto 1.017—PRC La Florida, D.O. 10-10-2012 (LeyChile) |

| La Granja | 2019 | Decreto 2.045—Actualización PRC La Granja, D.O. 21-11-2019 (LeyChile) |

| La Pintana | 2020 | Decreto 2.160—Actualización PRC La Pintana, D.O. 15-12-2020 (LeyChile) |

| La Reina | 2018 | Decreto 1.576—Actualización PRC La Reina, D.O. 30-08-2018 (LeyChile) |

| Las Condes | 2014 | Decreto 1.354—Actualización PRC Las Condes, D.O. 12-12-2014 (LeyChile) |

| Lo Barnechea | 2013 | Decreto 1.295—PRC Lo Barnechea, D.O. 05-11-2013 (LeyChile) |

| Lo Espejo | 2016 | Decreto 1.498—Actualización PRC Lo Espejo, D.O. 17-05-2016 (LeyChile) |

| Lo Prado | 2011 | Decreto 942—PRC Lo Prado, D.O. 08-09-2011 (LeyChile) |

| Macul | 2017 | Decreto 1.410—Actualización PRC Macul, D.O. 05-03-2017 (LeyChile) |

| Maipú | 2019 | Decreto 2.005—Actualización PRC Maipú, D.O. 02-10-2019 (LeyChile) |

| Ñuñoa | 2013 | Decreto 1.280—Actualización PRC Ñuñoa, D.O. 20-02-2013 (LeyChile) |

| Peñalolén | 2014 | Decreto 1.346—Actualización PRC Peñalolén, D.O. 26-09-2014 (LeyChile) |

| Providencia | 2016 | Decreto 1.523—Actualización PRC Providencia, D.O. 10-11-2016 (LeyChile) |

| Pudahuel | 2018 | Decreto 1.601—Actualización PRC Pudahuel, D.O. 25-11-2018 (LeyChile) |

| Puente Alto | 2015 | Decreto 1.132—Actualización PRC Puente Alto, D.O. 18-04-2015 (LeyChile) |

| Quilicura | 2020 | Decreto 2.203—Actualización PRC Quilicura, D.O. 04-12-2020 (LeyChile) |

| Quinta Normal | 2012 | Decreto 1.021—PRC Quinta Normal, D.O. 22-10-2012 (LeyChile) |

| Recoleta | 2018 | Decreto 1.595—Actualización PRC Recoleta, D.O. 13-12-2018 (LeyChile) |

| Renca | 2019 | Decreto 1.991—Actualización PRC Renca, D.O. 10-09-2019 (LeyChile) |

| San Joaquín | 2017 | Decreto 1.444—Actualización PRC San Joaquín, D.O. 05-05-2017 (LeyChile) |

| San Miguel | 2013 | Decreto 1.312—PRC San Miguel, D.O. 15-11-2013 (LeyChile) |

| San Ramón | 2016 | Decreto 1.551—PRC San Ramón, D.O. 28-11-2016 (LeyChile) |

| Santiago | 2021 | DEC.Secc.2da Nº 6847 D.O. 02-12- 2021 (Municipalidad Santiago) |

| Vitacura | 2015 | Decreto 1.178—Actualización PRC Vitacura, D.O. 03-09-2015 (LeyChile) |

Appendix B. Methodological Appendix

This research harnessed artificial intelligence to perform a detailed linguistic interrogation of the regulatory vernacular embedded within Greater Santiago’s municipal planning ordinances, thereby deepening the technical rigour of every analytical stage. The exercise was exploratory rather than definitive: its chief aim was to test AI’s utility as an auxiliary instrument for synthesising large-scale urban regulations that resist straightforward comparison because of their sheer volume and complexity. To guarantee methodological transparency and replicability, the constituent elements and operational sequence are described in full below.

The primary corpus comprised the 31 most current normative instruments issued across 33 municipalities in Greater Santiago. PDFs were harvested from official municipal portals and from the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development, then renamed according to a strict convention—MUN_ID_Version_Date.pdf—and filed within a municipality-by-year directory hierarchy. Each document was paired with a YAML manifest (manifesto.yaml) recording mandatory metadata: municipality identifier, issuing body, publication date (YYYY-MM-DD), version code, source URL, and a SHA-256 checksum, enabling comprehensive traceability and version auditing.

To ensure maximal textual fidelity, a Python-based processing pipeline—augmented by AI routines—handled extraction. Native text was first captured via PyMuPDF’s PDFStream layer; whenever the yield fell below 85 percent of the expected character count (estimated from page geometry), the system automatically invoked Tesseract OCR v4.1.1 with a composite language model (Spanish, English, French). A quality-control module benchmarked recovered word counts against a typographic baseline; sub-threshold results triggered the OCR fallback. Outputs were saved as .txt files retaining the original filenames and logged with document_id, extraction_mode (text/ocr), recovery_rate (percent), and processing_time (seconds).

All texts then underwent cleaning and normalisation. A suite of empirically calibrated regular expressions—derived from a 200-page pilot—expunged routine headers and footers (municipal names, logos, pagination), watermarks, scanning artefacts, intrusive line breaks (replaced by single spaces), tab characters, and redundant whitespace. These patterns were catalogued in cleaning_patterns.json, each entry specifying pattern, replacement, contextual note, and execution priority. The cleansing proceeded in two passes: an initial coarse filter followed by a fine-grained polish.

The clean text was then parsed using Python and the lark-parser library to reconstruct the typical hierarchy of an ordinance:

- Title (regex: ^ORDENANZA\s+.*)

- Chapter (^CAPÍTULO\s+\w+)

- Article (^Artículo\s+\d+)

- Section (^\d+.\d+)

- Clause: remaining paragraph text

Each segment was serialized into a JSON object with the following attributes:

{

“province”: “Santiago”,

“municipality”: “Las Condes”,

“chapter”: “III”,

“article”: 27,

“section”: “27.1”,

“text”: “El antejardín…”

}

All JSON outputs were validated against JSON Schema Draft-07, ensuring both type integrity and the presence of every required field; this procedure facilitated the consolidation of a single dataset for downstream linguistic analysis. The validated files were ingested into a pandas DataFrame whose harmonised schema comprised the columns municipality, chapter, article, section, text, length, year, and extraction_method. Two supplementary variables captured the token count and whether the source text originated from native extraction or OCR. Lemmatisation of the text column was carried out with spaCy’s es_core_news_md pipeline, augmented by custom rules that preserved domain-specific nomenclature—such as “RDE”, “PRC”, and “FOCUS”. Tokenisation acknowledged multi-word expressions (for instance, “unidad vecinal” remained a single token), while stopword elimination drew on a curated legal-urban list of 150 phrases (e.g., “el presente”, “conforme a”). The resulting DataFrame was therefore fully readied for model training and evaluation.

Findings were organised through a supervised annotation campaign anchored to six conceptual dimensions: zoning, land use, subdivision and plotting, mobility and transport, citizen participation, and sustainability and environment. A stratified corpus of 1800 clauses—sixty per ordinance, spanning all municipalities—was independently annotated by two coders; Cohen’s κ of 0.82 surpassed the 0.80 reliability benchmark, with residual discrepancies settled in joint adjudication sessions.

Semantic modelling proceeded via multi-label classification using XLM-RoBERTa (355 million parameters) fine-tuned on the annotated set. Training employed a batch size of 16 with an AdamW optimiser (weight-decay 0.01); five-fold cross-validation produced macro-F1 scores ranging from 87 to 90 per cent across the six categories. In parallel, a semi-automated terminology extractor—modelled on SynchroTerm—generated bi- to tetra-grams, calculated TF-IDF and C-Value statistics, and filtered candidates through the POS template (ADJ)*(NOUN)+(NOUN)+. This yielded a lexicon exceeding 450 specialised terms in Chilean urban regulation, including densidad predial, coeficiente de ocupación, rasante and coeficiente de constructibilidad.

Every stage described above received AI assistance; nevertheless, all resultant tables underwent expert manual verification to rectify domain inconsistencies prior to the comparative analytics and visualisation phase. The AI then executed three quantitative diagnostics of municipal regulatory convergence: cosine similarity of mean TF-IDF vectors (rendered as a heatmap), computation of a normative-gap index, and co-occurrence mapping.

The triangulation of these methods revealed latent patterns (e.g., municipalities with notable gaps in “sustainability”), thematic asymmetries, and potential opportunities for regulatory harmonization. The scale of the dataset may render some insights more abstract than the often-situated detail of each ordinance in Chile. Yet, herein lies the value: the capacity to generate metropolitan-scale diagnostic insights-otherwise unfeasible manually-by linguistically integrating the semantic content across the regulatory corpus, a task uniquely enabled by large-scale AI models such as DeepSeek-R1.

Once classified, the regulatory data were aggregated and compared using cosine similarity to assess thematic alignment between municipalities. Normative gap indices were computed, measuring the relative absence of clauses across key categories (e.g., participation, green space, social housing). In parallel, co-occurrence analysis was applied to detect frequent or missing regulatory associations (e.g., density + road infrastructure).

The following municipalities were included: Cerro Navia, Conchalí, El Bosque, Huechuraba, Independencia, La Cisterna, La Florida, La Granja, La Pintana, La Reina, Las Condes, Lo Barnechea, Lo Espejo, Lo Prado, Macul, Maipú, Ñuñoa, Peñalolén, Providencia, Pudahuel, Puente Alto, Quilicura, Quinta Normal, Recoleta, Renca, San Joaquín, San Miguel, San Ramón, Santiago, and Vitacura.

The following municipalities were not included in the document:

Estación Central

Pedro Aguirre Cerda

It is important to note that not all municipalities within Greater Santiago currently possess a formal local development plan. This long-standing issue is in the process of being addressed by the relevant authorities. For this reason, at the time of conducting and drafting this study, the analysis was limited to the 31 municipal regulatory plans that are legally in force and officially enacted.

The “aims and norms shared” dimension assesses the explicit presence and coherent articulation of planning goals in each municipal plan, as well as the systematic inclusion of common instruments such as zoning, building regulations, road infrastructure, and public space standards. A score between 0.00 and 0.33 indicates that objectives are absent or vague and fail to constitute a systematic regulatory framework. Scores between 0.34 and 0.66 reflect defined but partial objectives and the presence of zoning with little articulation to other instruments. Values between 0.67 and 1.00 represent an explicit, comprehensive, and well-articulated regulatory framework in which instruments are coherently combined to guide urban development.

The “regulatory asymmetries” dimension evaluates the degree of fragmentation, inconsistency, or normative imbalance within each PRC, particularly where variations among subzones, land uses, or levels of regulatory stringency might reproduce socio-spatial inequality. Plans with high internal consistency and homogeneous, coherent norms score between 0.00 and 0.33. If justified normative differences are present without undermining overall unity, the score falls between 0.34 and 0.66. A score between 0.67 and 1.00 denotes significant internal asymmetries, with stark differences between zones lacking clear technical justification.

The “differential emphasis” category gauges whether the PRC articulates distinct priorities or approaches-such as citizen participation, social integration, sustainability, or regulatory innovation. Generic, non-differentiated plans score between 0.00 and 0.33. Where some thematic emphases exist without structural coherence, the score ranges from 0.34 to 0.66. A score between 0.67 and 1.00 is reserved for plans with clear, structuring emphases that include specific incentives, effective participation mechanisms, or explicit environmental or social approaches.

For “normative voids”, the rubric measures the absence of key categories such as intercommunal planning, social housing integration, or climate resilience. A plan that comprehensively addresses these dimensions scores between 0.00 and 0.33. If relevant gaps are present-e.g., lack of social integration provisions or climate policy-the range is 0.34 to 0.66. Severe gaps, reflected in incomplete or fragmented responses to contemporary urban challenges, result in scores between 0.67 and 1.00.

Finally, the “omissions detected” dimension assesses the omission of elements critical to equity and urban quality, including standards for green areas, universal accessibility, multimodal integration, or binding public participation. Where the PRC explicitly includes most of these elements, the score ranges from 0.00 to 0.33. Partial or weak inclusion results in scores between 0.34 and 0.66. Systematic or widespread omissions, particularly regarding core issues, are scored between 0.67 and 1.00.

This article was originally written in Spanish as part of a broader strategy to interpret the findings drawn from the analyzed regulatory texts. Once both the article and the accompanying analyses were complete, the manuscript was translated into English using an interpretative approach. The translated version was subsequently reviewed using the same DeepSeek-R1 workflow, with the aim of identifying possible misinterpretations and refining the ways in which the methods and arguments were articulated.

This study has three main methodological limitations. First, the corpus was limited to the 31 legally enacted Planes Reguladores Comunales (PRCs), excluding municipalities like Estaci√≥n Central and Pedro Aguirre Cerda, which are still drafting ordinances. This restricts the study’s metropolitan coverage. Second, the quality of the documents varies significantly. Some PDFs contain scanned pages with fragmented text, which reduces OCR accuracy and may lead to omitted clauses during data extraction. Third, classifications based on large language models (LLMs) risk contextual misinterpretation, as Chilean legal terminology often has subtle variations across communes.

To mitigate these constraints, it was implemented a three-step rationalization strategy. Coverage gaps were acknowledged by explicitly flagging missing communes and by designing the pipeline to ingest new ordinances as they are promulgated in the future. OCR uncertainty was addressed through a dual-extraction protocol-PyMuPDF followed by threshold-triggered Tesseract-OCR-supplemented by manual spot checks on low-recovery files. Finally, potential semantic drift was reduced by fine-tuning DeepSeek-R1 on a stratified, expert-annotated sample and by instituting an iterative validation loop in which municipal planners reviewed model outputs for local accuracy.

References

- Abizadeh, A. Legislature by Lot: Transformative Designs for Deliberative Governance; Gastil, J., Wright, E.O., Eds.; The Real Utopias Project; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-78873-608-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bento, A.M.; Franco, S.F.; Kaffine, D.T. Effectiveness of Housing Revitalization Subsidies in the Presence of Zoning. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2011, 41, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo, R.; Segovia, M.; Wahr, C.; Thenoux, G. Superpave Zoning for Chile. Rev. Ing. Constr. 2017, 32, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves Franca, S.L. Housing public policies in the Urban Expansion Zone of Aracaju-SE, Brazil. In Ciudades En Construccion Permanente: Destino de Casas Para Todos? Vol Ii; Barreto, T.B., Mancilla, M.R., Espinosa, J.E., Eds.; Editorial Univ Abya-Yala: Cuenca, Ecuador, 2015; Volume 2, pp. 279–301. ISBN 978-9942-09-265-6. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, B.R.; Carvalho-Ribeiro, S.M.; Maia-Barbosa, P.M. A Multiscale Analysis of Land Use Dynamics in the Buffer Zone of Rio Doce State Park, Minas Gerais, Brazil. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 935–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjorgjevska, E.; Mirceva, G. Content Engineering for State-of-the-Art SEO Digital Strategies by Using NLP and ML. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Congress on Human-Computer Interaction, Optimization and Robotic Applications (HORA), Ankara, Turkey, 11–13 June 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Linder-Pelz, S.; Hall, L.M. The Theoretical Roots of NLP-Based Coaching. Coach. Psychol. 2007, 3, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dPrix, W.; Schmidbaur, K.; Bolojan, D.; Baseta, E. The Legacy Sketch Machine: From Artificial to Architectural Intelligence. Archit. Des. 2022, 92, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, F.; Kumar, A.; Upadhyay, A.; Chokshi, H.; Trinkūnas, V.; Magda, R. Property Management Enabled by Artificial Intelligence Post COVID-19: An Exploratory Review and Future Propositions. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2022, 26, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M. Natural Language Processing for Urban Research: A Systematic Review. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkley, C.; Stahmer, C. What Is in a Plan? Using Natural Language Processing to Read 461 California City General Plans. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2024, 44, 632–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mleczko, M.; Desmond, M. Using Natural Language Processing to Construct a National Zoning and Land Use Database. Urban Stud. 2023, 60, 2564–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, A.; Mena Valdés, J.A.; Montes Marín, M. Communal development plan: The governing instrument of municipal management in Chile? Revista INVI 2016, 31, 173–200. Available online: https://revistainvi.uchile.cl/index.php/INVI/article/view/62723 (accessed on 1 April 2025). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Navarrete-Hernandez, P.; Toro, F. Urban Systems of Accumulation: Half a Century of Chilean Neoliberal Urban Policies. Antipode 2019, 51, 899–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicuña, M. El marco regulatorio en el contexto de la gestión empresarialista y la mercantilización del desarrollo urbano del Gran Santiago, Chile. Revista INVI 2013, 28, 181–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Río, J.P.A.; del Campo Munnich, M. Governing Pudahuel: Applying Regime Analysis to a Chilean Study Case. JLAE 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stackhouse, J. Urban Land Use and the Entrepreneurial State: A Case Study of Pudahuel, Santiago Chile during the Military Regime (1973–1989). J. Lat. Am. Geogr. 2009, 8, 99–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpaci, J.L.; Infante, R.P.; Gaete, A. Planning Residential Segregation: The Case of Santiago, Chile. Urban Geogr. 1988, 9, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, A.; Bucci, F.; Palma, C.; Munizaga, J.; Montre-Águila, V. Development, Urban Planning and Political Decisions. A Triad That Built Territories at Risk. Nat. Hazards 2021, 109, 1935–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Pulido, J.A.; Mojica, A.; Bruner, A.; Guevara-Sangines, A.; Simon, C.; Vasquez-Lavin, F.; Gonzalez-Baca, C.; Infanzon, M.J. A Business Case for Marine Protected Areas: Economic Valuation of the Reef Attributes of Cozumel Island. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicuña, M. Planificación Metropolitana de Santiago. Rev. Iberoam. Urban. 2017, 13, 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- McCawley, D.G. The Political Economy of Land Use Governance in Santiago, Chile and Its Implications for Class-Based Segregation. SSRN 2012, 47, 119–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegras, C.; Stewart, A.; Forray, R.; Hidalgo, R.; Figueroa, C.; Duarte, F.; Wampler, J. Designing BRT-Oriented Development. In Restructuring Public Transport Through Bus Rapid Transit: An International and Interdisciplinary Perspective; Munoz, J., PagetSeekins, L., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2016; pp. 181–207. ISBN 978-1-4473-2618-2. [Google Scholar]

- Beguin, J.A.P.; Reyes, M.I.P. Los Primeros Planes Intercomunales Metropolitanos de Chile. Volumen I: Los Planes Para Santiago de Chile 1960–1994; Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo Universidad de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2016; ISBN 978-956-8556-05-1. [Google Scholar]

- Vicuña, M.; Urbina-Julio, A. “Alcánzame Si Puedes”: Ajustes y Calibraciones de La Normativa Urbana Tras La Verticalización En El Área Metropolitana de Santiago. Eure 2023, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Morales, E. Gentrification in Santiago, Chile: A Property-Led Process of Dispossession and Exclusion. Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 1109–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Morales, E.J. Real Estate Market, State-Entrepreneurialism and Urban Policy in the “gentrification by Ground Rent Dispossession” of Santiago de Chile. J. Lat. Am. Geogr. 2010, 9, 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pablo, P.; Andrea, B.; Gonzalo, P.-V.; Emilio, M. La evaluación del espacio público de ciudades intermedias de Chile desde la perspectiva de sus habitantes: Implicaciones para la intervención urbana. Territorios 2018, 39, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlack, E.; Vicuna, M. Highly Influential Normative Components Regarding the New Morphology of Metropolitan Santiago: A Critical Review of “Harmonic Set”. Eure-Rev. Latinoam. Estud. Urbano Reg. 2011, 37, 131–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicuña, M.; Pumarino, N.; Urbina, A. Payment for Impacts in Intensive Residential Densification Projects in the Metropolitan Area of Santiago: Critical Analysis of the New Chilean Legislation of Contributions to Public Space [Pago Por Impactos En Proyectos de Densificación Residencial Intens. Eure 2020, 46, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, R.; Alvarado, V.; Volker, P.; Arenas, F.; Salazar, A. Metropolitan Coastal Planning in Chile: From a Regulation Prospect to a Coopted Planning (1965–2014) [Ordenamento Litorâneo Metropolitano No Chile: Da Expetativa de Regulamentação Para o Planejamento Cooptado (1965–2014)]. Cuad. Vivienda Urban. 2015, 8, 206–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliste, E.; di Méo, G.; Guerrero, R. Ideologies behind the Development and Construction of the Metropolitan Area of Concepción (Chile). Ann. Geogr. 2013, 123, 662–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, C.; Gómez, R.; Hidalgo, R. Expresión Territorial de La Fragmentación y Segregación; Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos: Cuernavaca, Mexico, 2016; ISBN 978-607-8434-99-2. [Google Scholar]

- Symmes, L.R. Vertical City: The “New Form” of Precarious Housing Commune of Estación Central, Santiago de Chile [Ciudad Vertical: La “Nueva Forma” de La Precariedad Habitacional Comuna de Estación Central, Santiago de Chile]. Revista 2017, 180, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas Symmes, L.; Cortés Salinas, A.; Moreno, D. Santiago, the Non-City? Destruction, Creation, and Precariousness of Verticalized Space. In Urbicide; Carrión Mena, F., Cepeda Pico, P., Eds.; The Urban Book Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2023; pp. 865–890. ISBN 978-3-031-25303-4. [Google Scholar]

- Mikelionienė, J.; Motiejūnienė, J. Corpus-Based Analysis of Semi-Automatically Extracted Artificial Intelligence-Related Terminology. J. Lang. Cult. Educ. 2021, 9, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).