Industrial Relocation and Urban Restructuring: Between Decline and Global Connectivity in Setúbal

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- To examine how deindustrialisation and integration into GNCS have transformed SetPe’s economic, social, and spatial structure.

- (2)

- To analyse the impacts of these transformations on working conditions and the socio-cultural life of the local working class.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Quantitative Research

2.1.1. Data Collection

2.1.2. Sample Coverage and Limitations

2.1.3. Research Focus

2.1.4. Data Analysis

2.2. Qualitative Research

2.3. Data Integration Strategy

2.4. Ethical Approval

2.5. Limitations

3. The Integration Process of the Portuguese Economy into the GNCS

4. Transition to Export-Oriented Industrialisation and GNCS

4.1. Conceptual Framework (GCCs, GVCs, GPNs, GNCS)

4.2. Upgrading/Downgrading & Labour Agency

4.3. Spatial Theories

5. Urban and Labour Transformation: A Historical Trajectory

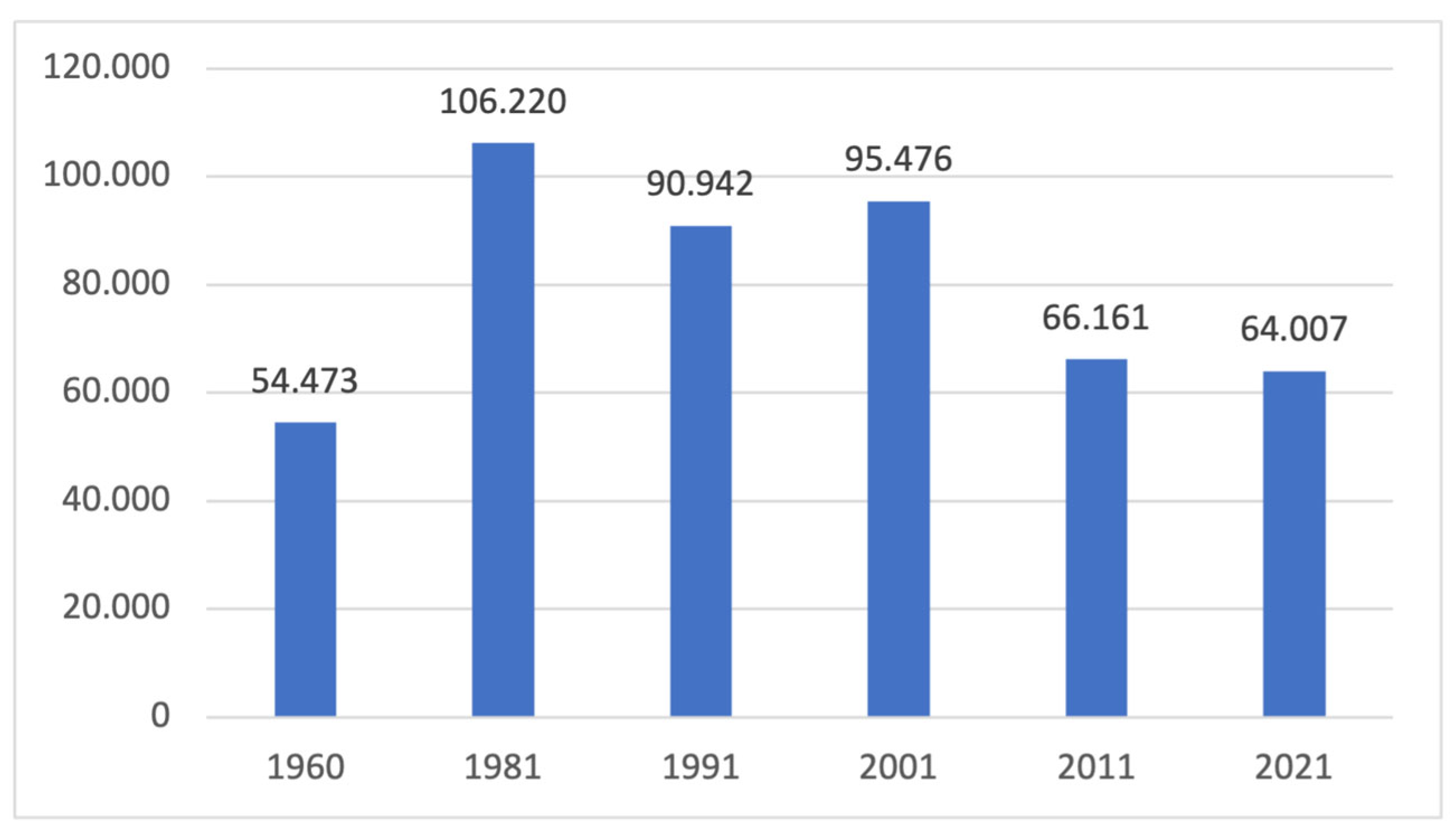

5.1. Industrial Consolidation and Worker Mobilisation (1960–1974)

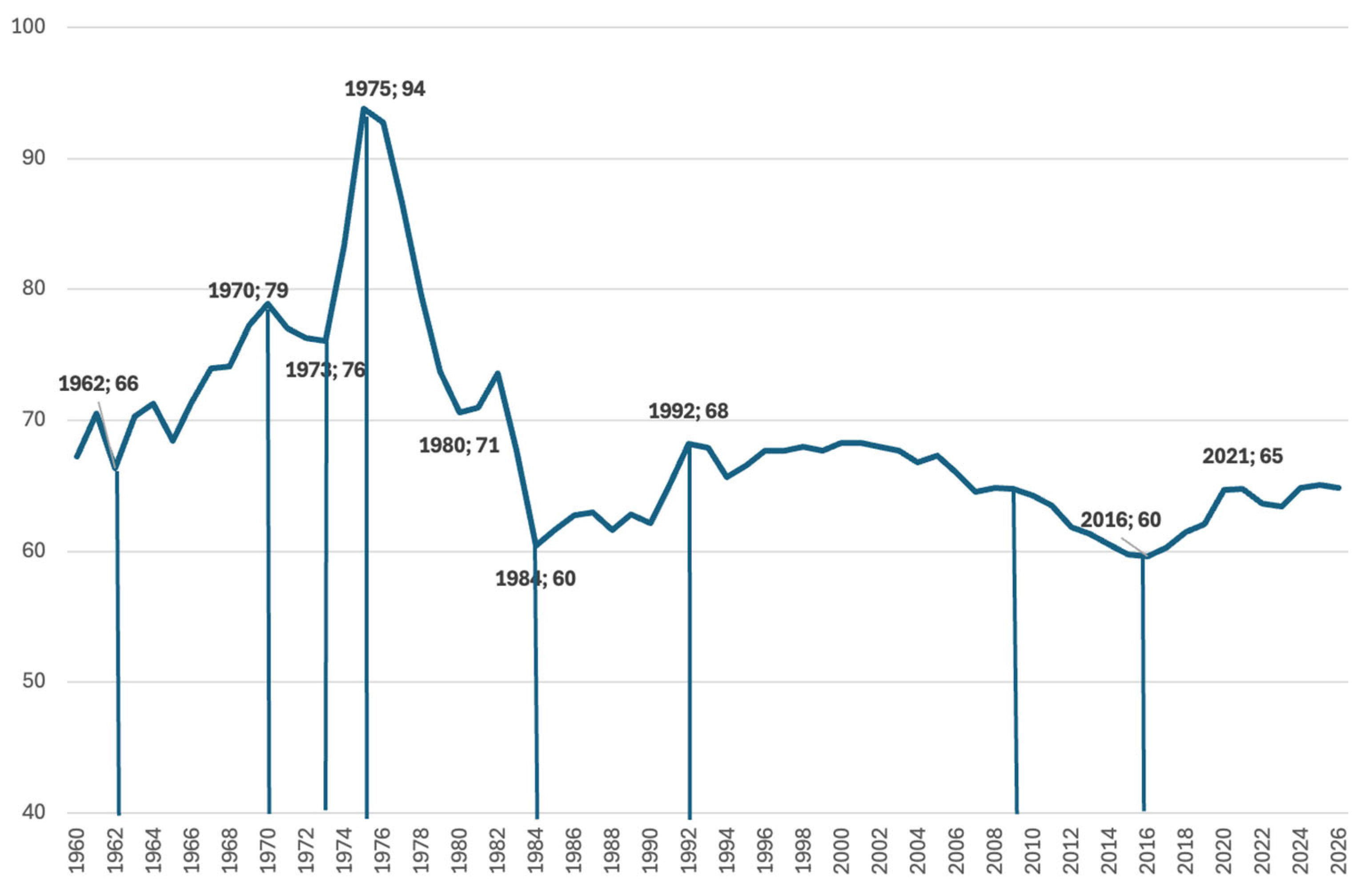

5.2. Revolutionary Restructuring and State Withdrawal (1974–1990)

5.3. Deindustrialisation and Global Reintegration (1990–Present)

5.4. Social and Economic Decline Across the SetPe

6. The Construction of the Global Factory as an Instrument of Development

6.1. Revival of the Automotive Sector in SetPe

6.2. Labour Conditions of the SetPe

6.3. Economic Decline of the SetPe

7. Results

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

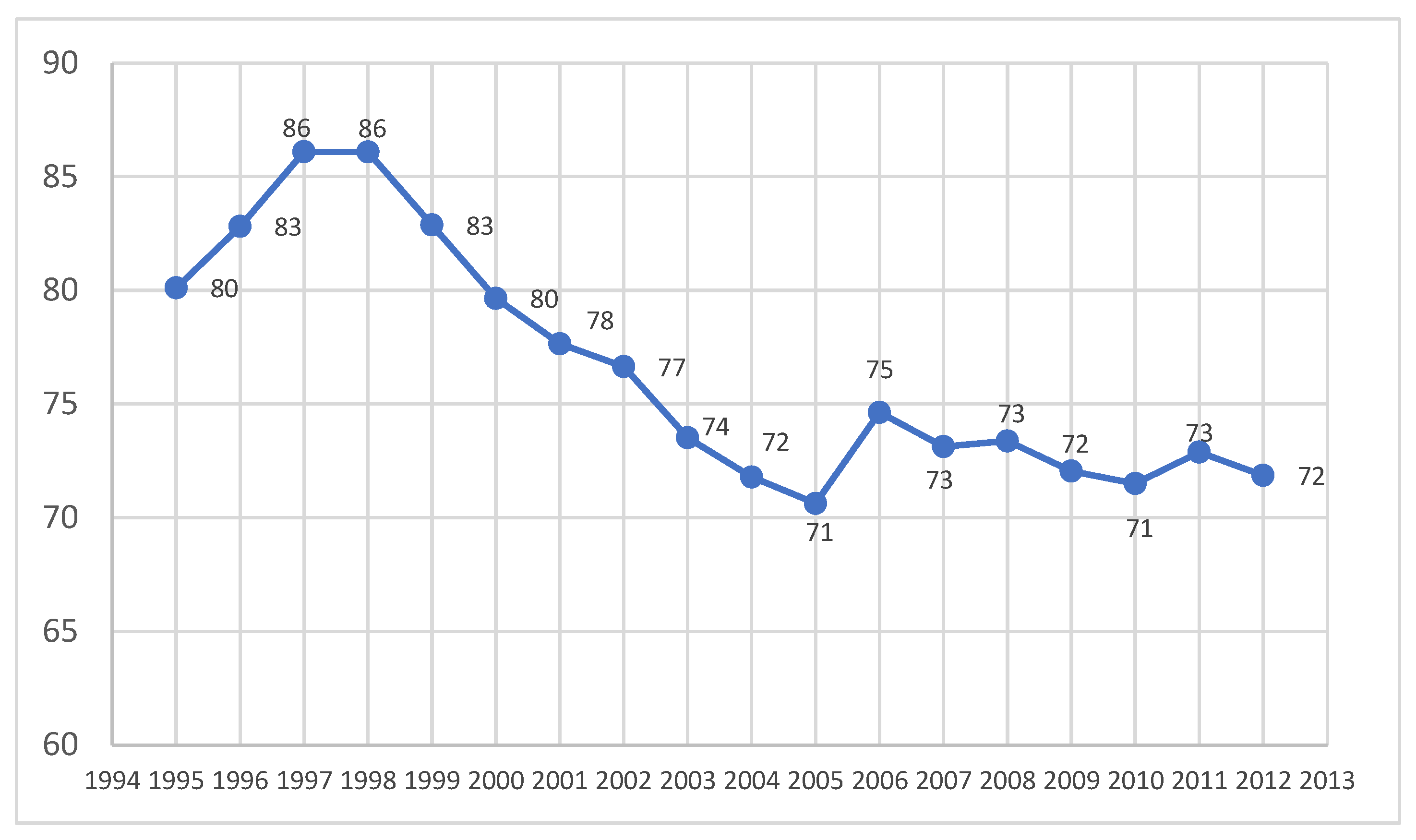

Appendix A. Comparison with the Kocaeli-Gebze Case

References

- Gereffi, G. Economic upgrading in global value chains. In Handbook on Global Value Chains; Ponte, S., Gereffi, G., Raj-Reichert, G., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, VIC, Australia, 2019; pp. 240–254. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J.; Dicken, P.; Hess, M.; Coe, N.; Yeung, H.W. Global production networks and the analysis of economic development. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2002, 9, 436–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, N.M.; Yeung, H.W. Global Production Networks: Theorizing Economic Development in an Interconnected World; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; ISBN 0198703902. [Google Scholar]

- Gereffi, G. The Organisation of Buyer-Driven Global Commodity Chains: How U.S. Retailers Shape Overseas Production Networks. In Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism; Gereffi, G., Korzeniewicz, M., Eds.; Praeger: Westport, CT, USA, 1994; pp. 95–122. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, T.K.; Wallerstein, I. Commodity Chains: Construct and Research. In Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism; Gereffi, G., Korzeniewicz, M., Eds.; Praeger: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bair, J.; Werner, M. Global Production and Uneven Development: When Bringing labor in isn’t Enough. In Putting Labor in Its Place: Labor Process Analysis and Global Value Chains; Newsome, K., Taylor, P., Bair, J., Rainnie, A., Eds.; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2017; pp. 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Selwyn, B. Poverty chains and global capitalism. Compet. Change 2019, 23, 71–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglioni, E.; Campling, L.; Coe, M.N.; Smith, A. Introduction: Labor Regimes and Global Production. In Labor Regimes and Global Production; Baglioni, E., Campling, L., Coe, N.M., Smith, A., Eds.; Agenda Publishing: London, UK, 2022; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Nicholson-Smith, D., Translator; Blackwell: Oxford, UK; Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; 454p. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change; Blackwell: Oxford, UK; Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. For Space; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2005; 223p. [Google Scholar]

- Öngel, F.S.; Gonçalves, J.; Nunes Da Silva, F. Setúbal Peninsula Worker Survey [SPSS Data File] (Inquérito Aos Membros Da Fiequimetal Sobre Condições De Vida E Alterações Climáticas). Mendeley Data, V2. 2024. Available online: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/bjnbrxwkjv/2 (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Eurostat. Income and Living Conditions. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/income-and-living-conditions/overview (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Eurostat. Population and Housing Censuses. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/population-demography/population-housing-censuses (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Clemente, E.F. Problemas y ritmos de la modernización económica peninsular en el siglo XX. Ayer 2000, 37, 191–217. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, Á.F.; Amaral, L.; Neves, P. Business groups in Portugal in the Estado Novo period (1930–1974): Family, power and structural change. Bus. Hist. 2016, 58, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes, J. Labor relations in a Portuguese shipyard. The case of Setenave: Case Studies 1950–2010. In Shipbuilding and Ship Repair Workers Around the World: Case Studies, 1950–2010; van der Linden, M., Murphy, H., Varela, R., Eds.; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Estatísticas Históricas Portuguesas; INE: Lisboa, Portugal, 2001; Available online: https://www.ine.pt/ngt_server/attachfileu.jsp?look_parentBoui=377094&att_display=n&att_download=y (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Rocha, E. Crescimento económico em Portugal nos anos de 1960-73: Alteração estrutural e ajustamento da oferta procura de trabalho. Análise Soc. 1984, 20, 621–644. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, S. Portugal in Ruins: From ‘Europe’ to Crisis and Austerity. Rev. Radic. Political Econ. 2019, 51, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.B.; Bastien, C.; Valerio, N. Privatisation and Transnationalisation in Portugal (1980–2005); Working Papers; GHES—Office of Economic and Social History: Lisboa, Portugal, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, O.H. Economic Stabilisation and Growth in Portugal; Occasional Paper No. 2; International Monetary Fund IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 1981; Reprinted September 1982. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Adjusted Wage Share, Percentage of GDP at Current Factor Cost. AMECO Database. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/db_indicators/ameco/documents/ameco7.zip (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Milberg, W.; Winkler, D. Outsourcing Economics: Global Value Chains in Capitalist Development; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fröbel, F.; Heinrichs, J.; Kreye, O. The New International Division of labor: Structural Unemployment in Industrialised Countries and Industrialisation in Developing Countries; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.J. Location Processes, Urbanisation, and Territorial Development: An Exploratory Essay. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 1985, 17, 479–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castree, N.; Coe, N.; Ward, K.; Samer, M. Spaces of Work: Global Capitalism and Geographies of Labor; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. Portugal—Public Enterprises in Portugal: Recommendations for Institutional and Financial Reforms; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 1986; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/699041468107956726/Portugal-Public-enterprises-in-Portugal-recommendations-for-institutional-and-financial-reforms (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Pike, A. Coping with deindustrialization in the global North and South. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2022, 26, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E.W. Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory; Verso Books: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Emery, J. Geographies of deindustrialization and the working-class: Industrial ruination, legacies, and affect. Geogr. Compass 2018, 13, e12417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G.; Kaplinsky, R. Introduction: Globalisation, Value Chains and Development. IDS Bull. 2001, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Backer, K.; Miroudot, S. Mapping Global Value Chains; OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 159; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G.; Fernandez-Stark, K. Global Value Chain Analysis: A Primer. Center on Globalization, Governance & Competitiveness; Duke University: Durham, NC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, H.W.; Coe, N.M. Toward a Dynamic Theory of Global Production Networks. Econ. Geogr. 2014, 91, 29–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komlosy, A.; Music, G. (Eds.) Global Commodity Chains and Labor Relations; Studies in Global Social History; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, B.J. Forces of Labor: Workers’ Movements and Globalization Since 1870; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Gereffi, G.; Barrientos, S. Global Value Chains, Upgrading and Poverty Reduction. SSRN Electron. J. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Selwyn, B. Social Upgrading and labor in Global Production Networks: A Critique and an Alternative Conception. Compet. Change 2013, 17, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.T. Global Production Networks, Relational Proximity, and the Sociospatial Dynamics of Market Internationalization in Bolivia’s Wood Products Sector. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2011, 102, 208–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.P.O. From iron to the industrial cloud. Nar. Umjet. 2020, 57, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIDPS. Operaçao Integrada De Desenvolvimento Da Peninsula De Setubal; Ministério Do Planeamentoe Da Administração Do Território Secretaria De Estado Do Planeamento E Do Desenvolvimento Regional: Lisbon, Portugal, 1990; Available online: https://www.ccdr-lvt.pt/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Operacao-Integrada-Desenvolvimento-Peninsula-Setubal-OIDPS-QCA-I.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Ferrão, J. A Indústria em Portugal: Estruturas produtivas e sociais em contextos regionais e diversificados. Finisterra 1988, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Governo de Portugal. Estratégia Para O Crescimento, Emprego E Fomento Industrial 2013–2020. Available online: https://www.historico.portugal.gov.pt/pt/o-governo/arquivo-historico/governos-constitucionais/gc19/os-ministerios/mee/documentos-oficiais/20130425-ecefi.aspx (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Nunes, A.B.; Mata, E.; Valério, N. Portuguese economic growth 1833–1985. J. Eur. Econ. Hist. 1989, 18, 291–330. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). Per Capital Gross Domestic Product (Portugal), World Economic Outlook Database. October 2023. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2022/October/select-countries?grp=995&sg=All-countries/Advanced-economies/Euro-area (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Pordata. Employment According to the Census: Total and by Sector of Economic Activity. INE—General Census Data X, XII, XIII, XIV, XV and XVI, Last Updated: 2023-03-07. Available online: www.pordata.pt (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- European Commission. European Union Regional Policy and the Development of Less-Favoured Regions; European Communities: Luxembourg, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Risco. Plano de Urbanização do Território da Quimiparque e área envolvente; Proposta de Plano; Relatório Versão; Risco; Câmara Municipal do Barreiro: Lisbon Portugal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Queirós, M. Da teoria à prática na intervenção em Brownfield: A regeneração da CUF/Quimigal no Barreiro. In Actas do V Congresso da Geografia Portuguesa; Congresso da Geografia Portuguesa: Guimarães, Portugal, 2004; Available online: https://www.apgeo.pt/files/docs/CD_V_Congresso_APG/web/_pdf/D12_15Out_Margarida%20Queiros.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Rua, L.M.R.B. A Desindustrialização no Concelho do Seixal e o Desafio da Conversão das Antigas Áreas Industriais na Perspetiva da Gestão Autárquica; Instituto Superior de Educação e Ciências: Lisboa, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, R.; Rajado, A. Work in the Portuguese shipyards of Lisnave: From the right to work to precariousness of employment. In Shipbuilding and Ship Repair Workers around the World: Case Studies, 1950–2010; van der Linden, M., Murphy, H., Varela, R., Eds.; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 339–363. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, N. Setúbal, uma baía aberta ao mundo: Retrato da economia no concelho; Câmara Municipal de Setúbal: Setúbal, Portugal, 2021; ISBN 978-972-9016-60-8. [Google Scholar]

- International labor Organization (ILO). Automotive Industry Employment Trends and Challenges in Portugal; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Amador, J.; Stehrer, R. Portuguese Exports in the Global Value Chains; Economic Bulletin and Financial Stability Report Articles and Banco de Portugal Economic Studies; Banco de Portugal, Economics and Research Department: Lisboa, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vale, M. Innovation and Knowledge Driven by a Focal Corporation: The Case of the Autoeuropa Supply Chain. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2004, 11, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AISET. Plataforma para o Desenvolvimento da Península de Setúbal, Estudo de Desenvolvimento Regional. Setúbal. 2018. Available online: https://aiset.pt/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/NUTS-Península-de-Setúbal-VCompleta-com-assinaturas.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Contas Regionais, Quadro D.1.5—Produto Interno Bruto Por Habitante e NUTS III (Preços Correntes; Anual). INE. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/ngt_server/attachfileu.jsp?look_parentBoui=97150348&att_display=n&att_download=y (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Iammarino, S.; Rodriguez-Pose, A.; Storper, M. Regional inequality in Europe: Evidence, theory and policy implications. J. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 19, 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2018, 11, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, J.; Theodore, N.; Brenner, N. Neoliberal Urbanism: Models, Moments, Mutations. SAIS Rev. Int. Aff. 2009, 29, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospers, G.-J. Industrial Heritage Tourism and Regional Restructuring in the European Union: The Case of the Ruhr Area. Eur. Plan Stud. 2022, 10, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öngel, F.S. Kapitalizmin Kıskacında Kent ve Emek: Gebze Bölgesi ve Otomotiv Sanayi Üzerine Bir Inceleme (City and Labor in the Grip of Capitalism: A Study on the Gebze Region and the Automotive Industry); Notabene Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 2012. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

| Category | Survey | Official | Explanation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wage 1 | 15% < €1.000; 67%€1.000–1.500; 13% > €1.500 | Avg. €1.370 | Manufacturing, SetPe (2023) | INE–MTSSS/GEP |

| Female ratio | 29% | 20% | Employees in ICEW, SetPe (2022) | INE–MTSSS/GEP |

| Average age | 43 | 45.5 | Skilled workers in ICEW, Portugal | INE, Census 2022 |

| Primary-school graduates | 28% | 31.7% | ICEW, Portugal | INE, Pop. & Housing Census 2020 Q4 |

| High-school graduates | 51% | 53.5% | ICEW, Portugal | INE, Pop. & Housing Census 2020 Q4 |

| University graduates | 21% | 14.3% | ICEW, Portugal | INE, Pop. & Housing Census 2020 Q4 |

| Union member- ship | 100% | ∼20–25% | Industrial workforce (region, est.) | INE (est.) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Öngel, F.S.; Gonçalves, J.; da Silva, F.N. Industrial Relocation and Urban Restructuring: Between Decline and Global Connectivity in Setúbal. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9050167

Öngel FS, Gonçalves J, da Silva FN. Industrial Relocation and Urban Restructuring: Between Decline and Global Connectivity in Setúbal. Urban Science. 2025; 9(5):167. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9050167

Chicago/Turabian StyleÖngel, Ferit Serkan, Jorge Gonçalves, and Fernando Nunes da Silva. 2025. "Industrial Relocation and Urban Restructuring: Between Decline and Global Connectivity in Setúbal" Urban Science 9, no. 5: 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9050167

APA StyleÖngel, F. S., Gonçalves, J., & da Silva, F. N. (2025). Industrial Relocation and Urban Restructuring: Between Decline and Global Connectivity in Setúbal. Urban Science, 9(5), 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9050167