Abstract

This article examines the dynamics of governance, stakeholder collaboration, and resource allocation in developing smart regions within peripheral territories. Using the Algarve (Portugal) as a case study—a region characterized by its peripheral status and reliance on tourism—this research explores efforts to integrate technological innovations and promote economic diversification. Data were collected from document research, stakeholder surveys, and interviews, indicating challenges including fragmented governance structures, resource constraints, and limited citizen engagement in innovation ecosystems. Drawing on comparative insights from other peripheral and more advanced smart region initiatives, this study highlights the critical role of public-private partnerships, active citizen participation, and context-specific governance strategies in achieving sustainable growth. While best practices provide valuable experiences, this study emphasizes the need for tailored solutions suited to each regional socioeconomic context.

1. Introduction

The term “smart region” has emerged as a strategic framework for fostering digital transformation and sustainable development in both metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas. Unlike smart cities, smart regions require an integrated, multi-level governance approach to bridge rural–urban divides, promote innovation ecosystems, and enhance economic resilience [1]. However, the successful implementation of smart region initiatives requires specific infrastructural, civic, and technological conditions that non-metropolitan areas often lack [2]. These deficiencies present unique challenges in adopting cohesive governance frameworks and inclusive innovation ecosystems. In peripheral areas like Portugal’s Algarve region, the absence of such structural elements is further exacerbated by an entrenched dependence on tourism.

While reliance on tourism has raised the Algarve’s economic profile in recent decades, generating the second-highest purchasing power in the country, it has also fostered structural vulnerabilities, including limited economic diversification and innovation capacity [3,4]. Recent studies underscore that this tourism overspecialization inhibits the development of other sectors and leaves the region vulnerable to external economic shocks, lacking the resources and historical dependencies required for adapting its governance frameworks to diversified areas of activity [5].

Existing policies, such as the Algarve Smart Region (RIA) and Algarve Tech Hub, seek to demonstrate the potential for innovation-driven growth through collaborative governance. These projects, aligned with the Algarve Smart Specialization Strategy (S3), aim to foster economic diversification and reposition the local ecosystem as a lifestyle hotspot and innovation hub [6,7]. Yet, empirical analyses of their effectiveness in governance and stakeholder collaboration have been limited. Furthermore, the role of public-private partnerships, citizen engagement, and institutional trust in shaping smart region governance remains understudied.

This article aims to help filling this gap by discussing the governance structures, stakeholder dynamics, and resource allocation strategies shaping the Algarve’s transformation into a smart region. The research mainly used secondary data from regional reports and qualitative data from stakeholder interviews [8] to evaluate the region’s performance across key governance dimensions. It provides insights for other peripheral regions facing similar socioeconomic and governance challenges by identifying critical governance bottlenecks.

The article is structured as follows. After introducing key concepts surrounding the smart region debate, the article presents the Algarve’s transition, highlighting lessons learned from the experiences of other regions. The findings offer practical implications for policymakers, highlighting strategies to improve governance efficiency, strengthen stakeholder collaboration and promote sustainable growth. This study contributes for a reflexive perspective on smart regions development and adaptive governance in non-metropolitan contexts.

2. Smart Regions, Innovation Ecosystems, and Governance

2.1. Integrating Innovation Helixes for Collaborative Governance

Smart region governance involves collaborative mechanisms that apply innovative technologies to enhance decision-making processes [1]. In this article, a smart region refers to a region that utilizes technology and data-driven approaches to transform the territory, enhancing quality of life, stimulating economic growth, and addressing societal challenges. Central to this transformation is the engagement of citizens as both users of digital services and contributors to policy co-creation [2]. The ultimate goal of such a governance approach is to optimize human and natural resource management to improve the quality of life of the population across a region [9,10]. Evolving from its roots in smart cities, the concept of smart regions extends beyond urban centers to include peri-urban and rural areas [10]. This shift highlights the understanding that regions, not just cities, serve as fundamental units for addressing complex socioeconomic and environmental challenges through integrated governance and technology-driven strategies [11].

The concept of an innovation ecosystem is particularly useful for understanding the dynamics required for the emergence of a smart region. An innovation ecosystem is defined as a network of interdependent actors, activities, and institutions that collaborate and co-evolve to drive technological development and innovation [12]. Unlike traditional value chains, innovation ecosystems emphasize shared value creation through modular platforms integrating diverse assets, expertise, and complementary resources [3]. Three dimensions—interaction, resources, and governance—are essential for shaping effective innovation ecosystems [13]. Interaction refers to the diversity and interconnectedness of actors such as businesses, universities, and civic organizations. A strong culture of collaboration, mutual trust, and shared goals enhances self-organization and ecosystem resilience. This means building a diverse and inclusive entrepreneurial landscape. Resources, both tangible (like infrastructure and funding) and intangible (such as knowledge and institutional support), are the lifeblood of innovation. Key enablers include co-working spaces, incubators, digital networks, and intermediaries like financial institutions and educational entities, all contributing to ecosystem maturity through measurable outputs. Governance provides the strategic backbone, moving beyond transactional relationships to foster long-term, coordinated planning. It includes both formal structures—like policies and legal frameworks—and informal dynamics such as stakeholder recognition and alignment.

The foundation of smart region governance lies in integrating multiple innovation helices to generate consensus among different types of stakeholders, from governments to citizens and other local bodies [14]. These synergies span from basic information sharing to co-creation dynamics that utilize technology to gather opinions and attitudes from regional actors [15]. This study focuses on the quadruple-helix model, combining academia, government, businesses, and civil society to foster collaboration and inclusivity in regional development [16]. By emphasizing co-creation and adaptability, such an approach may help to enhance the regional capacity to address governance challenges [17].

The interconnectedness required between stakeholders in smart regions necessitates ongoing coordination and adaptation to integrate emerging entities within the region [18]. For instance, initiatives in peripheral areas highlight the crucial role of universities and local governments in driving this interconnectedness [19]. However, pressing challenges remain, such as reconciling municipal priorities [20], efficiently managing infrastructure [21], and balancing resource distribution across diverse jurisdictional frameworks [22].

A holistic approach is essential to overcome the failures inherent in the complex system of smart regions. As Ruhlandt [1] emphasized, the challenging triad of economic, societal, and environmental transformation necessitates merging digital and ecological practices to create people-centric regions. This emphasis on serving people must also address inclusivity across diverse social groups, ensuring fair and transparent access to services [23]. However, inclusivity remains a significant hurdle in peripheral regions where fragmented governance and the low digital literacy among marginalized communities exacerbate the existing inequalities [12]. Ensuring inclusivity in peripheral areas requires innovative and fair governance models in resource allocation and digital literacy [21].

By leveraging technologies like open data platforms and real-time analytics, digital transformation can foster transparency and strengthen trust between policymakers and civil society [24]. However, systemic vulnerabilities, such as inadequate cybersecurity measures [25] and the legitimation of the digital divide [20], remain barriers to realizing the full potential of digital transformations, particularly in the SMEs in peripheral regions [17]. Comprehensive policy frameworks prioritizing equitable digital access and robust data protection measures are necessary [18].

2.2. Learning from Smart Region Governance Implementation

Smart region governance has been successfully implemented in various contexts, ranging from highly digitized urban centers to peripheral and island regions with distinct socioeconomic constraints. Several well-established cases provide valuable insights into data-driven decision making, stakeholder engagement, and policy adaptation.

Prominent smart regions, such as Barcelona and Amsterdam, have emerged as global benchmarks in smart governance [21]. These cities have excelled in leveraging open data platforms, real-time analytics, and participatory governance to enhance decision-making processes [23]. Their approaches emphasize long-term investments in digital infrastructure, education, and citizen engagement, showcasing how smart governance can transform urban spaces into resilient and sustainable hubs of innovation [21].

For instance, Barcelona has implemented a comprehensive smart city strategy that integrates the Internet of Things, open data, and citizen co-creation to address urban challenges ranging from mobility and energy efficiency to social inclusion. Amsterdam has pioneered a collaborative governance model that brings together government, businesses, academia, and citizens to drive innovation and sustainable development across the city [26].

While Barcelona and Amsterdam have indeed emerged as global leaders in smart governance, their success stories may not be directly transferable to peripheral regions [22]. These metropolitan areas possess distinct advantages, such as robust digital infrastructure, higher levels of digital literacy, and greater financial resources, which may not be readily available in less-developed regions. Furthermore, the one-size-fits-all approach to smart governance can overlook the unique socioeconomic and geographical challenges faced by peripheral areas, potentially exacerbating existing inequalities [27].

In contrast to large metropolitan areas, peripheral and island smart regions must navigate distinctive governance, geographic, and economic challenges. In the Balearic Islands, the Smart Specialization Strategy (S3) focuses on diversification and modernization, aiming to reduce dependency on tourism and promote digital transformation in traditional industries [24]. Key initiatives include investments in renewable energy, digital tourism solutions, and SME capacity-building programs to align smart governance strategies with the islands’ economic and environmental priorities [28].

The unique challenges facing the achievement of smart regions in the Balearic Islands are multifaceted and require a tailored approach. These include addressing the fragmented governance structures across the islands, which can lead to conflicts in municipal priorities and the inefficient management of shared infrastructure and resources [29,30]. Additionally, the Balearic Islands face the challenge of bridging the digital divide, as marginalized communities often have low digital literacy, exacerbating existing socioeconomic inequalities. Overcoming these challenges necessitates innovative and inclusive governance models that prioritize equitable distribution of resources and investment in digital upskilling programs tailored to the specific needs of the islands’ diverse populations [24].

Crete, a major participant in the Smart Islands Initiative, has emerged as a pioneering example of smart governance in a peripheral region through the DAFNI Network. The Greek island has developed a holistic approach that integrates sustainable resource management and digital public services. Recognizing the unique challenges faced by island territories, Crete has emphasized the implementation of energy-efficient infrastructure, comprehensive digital literacy programs, and technology-driven agricultural practices [31]. This tailored approach to smart region development underscores the importance of adapting smart governance strategies to the specific socioeconomic conditions of the local context. Through its multifaceted initiatives, Crete is demonstrating how smart governance can drive innovation and sustainable development in peripheral and island regions.

Alongside other peripheral regions and islands, such as the Balearic Islands and Sardinha, Corsica has advocated for region-specific EU policies that account for the economic and infrastructural disparities of island territories [32]. A core aspect of Corsica’s smart governance strategy is leveraging digital co-creation platforms, enabling citizen participation in policymaking while improving public service accessibility. By exploring the experiences of these peripheral and island regions, it becomes evident that effective smart governance in non-metropolitan areas requires a nuanced understanding of local contexts, inclusive stakeholder engagement, and a flexible and context-sensitive approach to policy implementation [29,33].

Beyond Europe, several international cases highlight how smart governance models can be adapted to regional needs. Singapore’s Smart Nation initiative represents a state-led, fully integrated smart governance framework that prioritizes data-driven decision-making, digital inclusion, and AI-driven services [34]. While the city-state benefits from a centralized governance model and advanced technological infrastructure, its strategy provides valuable lessons in digital transformation that can inform governance approaches in both urban and non-metropolitan regions [35]. Brazil has taken significant steps toward implementing smart governance principles in major urban centers, notably through the Rio Operations Center (COR), which integrates multiple data sources for real-time urban management [36]. Although this initiative primarily focuses on urban resilience and emergency response, it demonstrates how smart governance can address infrastructure and service delivery challenges in resource-constrained environments. Colombia’s Medellín District, once known for urban instability, has successfully reinvented itself as a regional innovation hub, leveraging smart city strategies to drive economic recovery [37]. The Medellín Innovation District fosters entrepreneurial ecosystems, digital capacity building, and participatory urban planning, offering examples into how smart governance can drive inclusive economic development in Latin America.

3. Methodology

This study aimed to analyze the ongoing intention of the Algarve to transition into a smart region. By examining the interplay between innovation, technology, and regional development, this research sought to address the unique challenges faced by peripheral areas.

Central to this investigation were the vulnerabilities stemming from the Algarve’s dependence on tourism, constrained resource allocation, and limited citizen engagement. This research was guided by key questions: What governance dimensions are most critical for the Algarve’s transition into a smart region? How do stakeholder dynamics influence the region’s capacity for innovation and technological integration? What resource limitations obstruct progress, and how can they be addressed? Finally, how does the Algarve’s innovation ecosystem compare with those in similar peripheral regions?

The research design facilitated the identification of critical governance dimensions that influence the Algarve’s transition into a smart region and the evaluation of the role of key stakeholders, including policymakers, academic institutions, private enterprises, and citizens, in shaping this transformation. This qualitative approach was selected to bridge the gap between theoretical governance models and practical policy implementation.

By combining structured policy assessments with expert insights, the study ensured that both institutional and experiential dimensions of governance were captured. This dual focus ensured that both structural and processual aspects of governance were explored, capturing the interplay between institutional mechanisms and stakeholder dynamics. This approach was informed by governance and innovation ecosystem frameworks, as widely discussed in the literature [1,34]. The study also drew on comparative cases to contextualize findings within a broader European framework, emphasizing the Algarve’s unique socioeconomic characteristics.

The data collection strategy ensured both breadth and depth in understanding the Algarve’s smart region governance and innovation challenges. Primary data were collected through exploratory interviews. These interviews were conducted with ten strategic stakeholders, selected through purposive sampling, ensuring representation across the key sectors involved in regional governance and innovation initiatives, from government agencies, the University of Algarve, and regional businesses to community organizations, allowing the collection of qualitative perceptions into the challenges and opportunities associated with the Algarve’s transition. Each participant was selected based on expertise, ensuring that the insights gathered would reflect high-level governance and policy considerations.

The interviews followed a semi-structured format, allowing for the exploration of predetermined themes while accommodating emergent topics identified by participants. The script design was based on a thorough literature review on innovation ecosystems, ensuring that questions were contextually relevant and scientifically validated. Additionally, during the interviews the respondents evaluated governance practices, infrastructure adequacy, and innovation capabilities using a five-point Likert scale.

Secondary data from regional reports, such as the Algarve Smart Region (RIA) project documentation (concluded in 2023) and the ALGARVE STP mapping study of the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) sector [8], contextualized findings within broader regional trends.

Additionally, comparative data from the European Union’s 2023 Regional Innovation Scoreboard provided benchmarks for assessing the Algarve’s performance relative to other regions [22]. These secondary sources were triangulated with primary data to enhance the validity of the findings and ensure consistency across different data collection methods.

4. The Potential of the Algarve to Be a Smart Region

4.1. Overview of This Case Study

The Algarve region, located in southern Portugal, is renowned for its tourism-centric economy and stunning natural landscapes. The Algarve’s historical reliance on tourism has both driven economic success and created significant vulnerabilities. While tourism remains a primary revenue generator, this dependency has hindered diversification into sectors that could sustain long-term growth. Tourism accounts for approximately 70% of the Algarve’s GDP, while knowledge-intensive and technology-driven sectors remain underdeveloped [22]. As a result, the region faces economic instability, limited R&D investment, and constrained innovation capacity [4].

The COVID-19 pandemic further underscored these vulnerabilities [38], exposing the region’s overreliance on tourism and the pressing need for diversification leading to a sharp decline in the regional GDP and increase in unemployment, particularly in the tourism and service sectors [39]. This dynamic reflects the ‘Dutch disease’ phenomenon, where economic reliance on a dominant sector, such as tourism, stifles growth in emerging industries like ICT or agro tech [3,4].

This problem has been addressed through the Algarve Smart Specialization Strategy (RIS3 Algarve) [40]. This strategy identifies a variety of key strategic priorities, with ICT presented as a key sector to drive economic dynamics and foster technological growth. The smart region framework emerged as a strategic response to regional challenges, building on the S3 platforms established through this policy process to intensify technological integration across sectors [7].

4.2. Regional Smart Governance and Innovation Performance

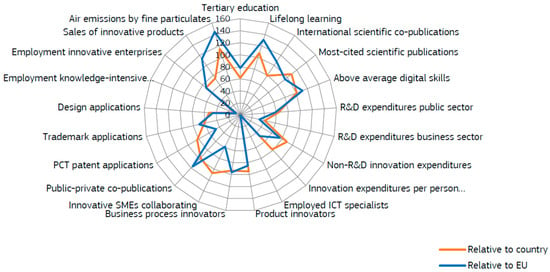

Figure 1 presents a comparative analysis of the Algarve’s performance in key innovation metrics relative to national and EU averages. The radar chart captures tertiary education rates, employment in innovative enterprises, PCT patent applications, and public-private co-publications, clearly representing the region’s competitive position within Portugal and the EU.

Figure 1.

Innovation metrics for the Algarve, EU Regional Innovation Scoreboard 2023 [22]. The orange line indicates the Algarve’s performance relative to the national average (Portugal). The blue line represents the Algarve’s performance relative to the broader EU average.

The Algarve demonstrates strong performance in tertiary education and lifelong learning, exceeding both national and EU benchmarks. This suggests that the region benefits from a well-educated workforce and a strong academic foundation, particularly due to the presence of the University of Algarve and regional research institutions. Additionally, the Algarve performs relatively well in international scientific co-publications and most-cited scientific publications, indicating that its academic research output is competitive at an international level.

For example, while the region excels in promoting lifelong learning and digital skills, these advantages are not yet translating into measurable outputs like high levels of product or process innovation. The R&D expenditures in the business sector suggest that private enterprises are not investing sufficiently in research or technological advancement. Non-R&D innovation expenditures remain low, suggesting that firms are not actively engaging in non-traditional forms of innovation, such as process optimization, design thinking, or technology adoption. Product and process innovation remains significantly lower than both the national and EU averages. This indicates that despite strong knowledge creation, the Algarve struggles to translate research into commercially viable products and services.

ICT specialist employment also lags behind, signaling a digital skill gap that hinders the region’s ability to transition into a smart economy. Similarly, the low percentage of innovative SMEs collaborating on R&D projects indicates that cross-sector partnerships between academia and business remain underdeveloped. This suggests that while knowledge creation is taking place, the mechanisms for integrating this knowledge into the broader economic landscape remain weak.

Bridging this gap requires targeted investments in R&D infrastructure and policies that incentivize private-sector engagement, a crucial driver of innovation and economic diversification [41]. While the region demonstrates strengths in tertiary education and international research collaboration, these advantages have not yet translated into high levels of private-sector investment in R&D or substantial innovation outputs. The radar chart underscores the need for a balanced strategy that builds on existing strengths while closing the performance gaps in areas critical to the Algarve’s smart region objectives [42].

The regional ICT sector has experienced notable growth, particularly during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. This sector now employs approximately 2500 workers, covering fields such as software development, cybersecurity, data analytics, and cloud computing, and generates an annual turnover of EUR 130 million, a significant increase from pre-pandemic figures, highlighting its growing role in the regional economy [8]. This growth reflects the sector’s increasing importance in the regional economy, particularly in high-value subfields such as IT consultancy, equipment trading, and digital innovation. A rising number of tech startups and scale-ups are benefitting from regional incubators and accelerator programs. This phenomenon, linked to the region’s touristic culture and lifestyle attributes, has also attracted digital nomads and remote tech workers, positioning the Algarve as an emerging hub for international professionals and companies leveraging Portugal’s digital-friendly policies.

While these developments indicate a positive trajectory, continued investment in ICT infrastructure, skill development, and funding incentives is needed to sustain growth, attract high-value foreign direct investment (FDI), and strengthen the Algarve’s competitive position in the European tech landscape.

To tackle its economic vulnerabilities, the Algarve has initiated transformative projects. The Algarve Smart Region (RIA) is the flagship initiative, seeking to establish a cohesive smart region strategy by fostering innovation, enhancing stakeholder collaboration, and addressing regional disparities. This project is spearheaded by the Algarve Regional Innovation Council (CIRA), which uses a quadruple-helix model (government, academia, business, and civil society) to foster collaboration and innovation. The RIS3 Algarve participatory governance approach ensured that diverse perspectives are integrated into the region’s strategic planning, enhancing inclusivity and alignment with regional needs. Through these initiatives, the Algarve aimed to position itself as an innovation-driven and resilient smart region, capable of sustaining long-term economic growth beyond tourism.

Another notable project is the Algarve Tech Hub, a collaborative brand established by the University of Algarve and licensed to regional innovation platforms such as Algarve Evolution. This initiative aims to position the Algarve as a globally competitive technology and innovation hub, leveraging its unique geographic, economic, and institutional assets to attract investment, facilitate knowledge exchange, and foster multi-sectoral collaboration.

The Algarve Tech Hub is strategically focused on five key technology sectors that align with the region’s unique strengths and economic goals. In hospitality tech, the hub supports the development of smart tourism solutions such as AI-driven customer service platforms, advanced digital booking systems, and big data analytics for more effective tourism management. Ocean tech initiatives are driving innovation in marine industries through sustainable fisheries, oceanic data analytics, and renewable energy technologies like offshore wind farms and wave energy. In the field of agro tech, the hub promotes precision agriculture and sustainable food production using IoT-enabled farm management, AI-powered climate modeling, and smart irrigation systems. Health tech efforts aim to improve regional healthcare accessibility by advancing e-health platforms, telemedicine solutions, and medical AI applications, particularly in response to the aging population. Lastly, energy tech projects are geared toward renewable energy integration, smart grid development, and energy efficiency, all contributing to Portugal’s broader decarbonization and sustainability objectives. By integrating these high-potential sectors, the Algarve Tech Hub serves as a driver of digital transformation, fostering entrepreneurial activity, R&D commercialization, and cross-sector partnerships that bridge the gap among academia, government, and private industry.

4.3. Governance Challenges and Regional Barriers

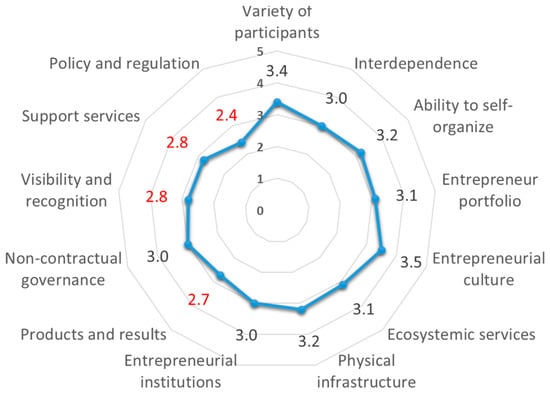

Governance plays a central role, influencing all other dimensions. For example, effective governance fosters sustainable economic growth [43], promotes citizen-centric mobility systems [44], and ensures environmental stewardship [45]. Effective governance underpins these initiatives, with the University of Algarve acting as a key driver of research, public–private partnerships, and innovation projects. The university’s leadership fosters collaborative governance through a quadruple-helix approach by engaging diverse stakeholders, government, private enterprises, academia, and civil society [6]. This model enables co-creation processes that address the Algarve’s complex economic and social challenges. Figure 2 highlights structural deficiencies in governance efficiency, ecosystem services, and entrepreneurial support systems. Fragmented policies and inconsistent regulations continue to hinder the implementation of smart region initiatives, delaying progress and limiting the scalability of innovation efforts. Inadequate policy coherence restricts high-tech industry development and deters investment in sectors essential for economic diversification. Moreover, public services and enterprises struggle with the high costs associated with digital transformation, creating additional barriers to progress [46].

Figure 2.

Governance, interaction, and resources in the Algarve’s ecosystem, Mean=3.0 (source: adapted from [9]).

The data from the ALGARVE STP (2022) report [8] underscore the region’s challenges in governance, with particularly low scores in policy coherence and support services impeding innovation growth. The radar chart illustrating the Algarve’s regional ecosystem performance across governance, interaction, and resource dimensions reveals significant disparities, with the region scoring poorly in areas contrast with moderate scores in others, suggesting that, while foundational elements are in place, strategic improvements are needed in governance support and ecosystem services.

In terms of interaction, while metrics like interdependence (3.4) and entrepreneurial culture (3.5) indicate a moderate foundation, the full potential of stakeholder collaboration remains untapped due to fragmented frameworks and limited mechanisms to foster consistent engagement. Regarding resources, although the region’s physical infrastructure scores moderately (3.2), deficiencies in ecosystem services and entrepreneurial institutions signal underutilized assets and a lack of cohesive platforms to support startups and innovation-driven ventures. In the area of governance, weak policies, limited support services, and low visibility hinder the region’s ability to attract investment and stimulate entrepreneurial growth. The particularly low score for as policy and regulation (2.4), support services (2.8) and visibility and recognition (2.8) underscores the insufficient support available to help businesses and institutions adapt to digital transformation and innovation challenges.

To address these challenges, enhancing support services through publicly funded programs can help enterprises, particularly SMEs, manage the costs of digital transformation. Finally, improving the region’s visibility and recognition by promoting the Algarve as an innovation hub through strategic branding and active participation in global innovation and entrepreneurial networks is essential. The University of Algarve’s initiatives, including the Algarve Tech Hub and the Algarve Smart Region (RIA), provide a foundation for addressing these gaps. However, as Figure 2 illustrates, sustained collaboration among stakeholders and robust policy reforms will be essential to overcoming the structural barriers to innovation.

4.4. Lessons from Smart Regions Governance

The Algarve’s transition to a smart region presents both significant hurdles and transformative potential. Overcoming entrenched dependencies and governance bottlenecks offers an opportunity to leverage the region’s natural and cultural assets while strengthening its innovation ecosystem. Specifically, the Algarve’s reputation as a global tourist destination and the presence of established institutions like the University of Algarve provide a strong foundation for innovation-driven growth.

The key governance challenges in developing smart regions include the fragmentation of policies, resource deficits, and policy gaps. Fragmented municipal policies undermine the implementation of cohesive, region-wide smart frameworks, with inconsistent data governance limiting interoperability and scalability. These inefficiencies restrict the collaboration across stakeholders and hinder the region’s ability to attract large-scale investments [6]. Resource deficits, such as insufficient infrastructure, limited skilled human capital, and financial constraints, exacerbate governance challenges, delaying the implementation of integrated systems and innovation-driven initiatives [47]. Additionally, gaps in coherent regulations, particularly concerning data security and privacy, erode trust and slow the adoption of digital solutions, underscoring the need for stronger policy alignment and resource investment.

Moreover, the quadruple-helix model, designed to promote cooperation among government, academia, businesses, and civil society, has encountered barriers in the Algarve. The limited digital literacy among the rural populations and the low trust in public institutions create obstacles for citizen engagement in governance processes [48]. As a result, smart region policies often fail to reflect the needs of marginalized communities, exacerbating existing socioeconomic inequalities. Without the wider adoption of participatory governance models and investment in digital inclusion, smart initiatives risk deepening the urban–rural divide rather than bridging it.

Additionally, the Algarve faces structural deficiencies in resource allocation, including insufficient funding for ICT infrastructure, gaps in human capital, and weak public–private partnerships (PPPs). The lack of targeted incentives to stimulate innovation in SMEs and emerging industries means that economic diversification beyond tourism remains slow, leaving the region vulnerable to external shocks. Furthermore, citizen engagement in governance processes remains limited, reflecting a broader disconnect between regional policymakers and civil society, exacerbated by digital literacy barriers and trust deficits in public institutions. While these governance challenges are significant, case studies from other peripheral and island regions provide valuable insight into how tailored smart governance strategies can drive regional innovation. The Balearic Islands, for instance, have pursued a Smart Specialization Strategy (S3) focused on reducing tourism dependency through investments in digital transformation, renewable energy, and technology-driven business innovation [24]. A major component of this strategy is strengthening SME participation in regional innovation ecosystems, ensuring that local businesses benefit from smart governance frameworks. However, the region continues to face governance inefficiencies due to jurisdictional fragmentation across its islands, requiring stronger policy coordination mechanisms.

Similarly, Crete has distinguished itself as a leader in smart governance among European islands, leveraging the Smart Islands Initiative to integrate sustainable resource management with digital public services. The island has prioritized investments in energy-efficient infrastructure, technology-enabled agriculture, and digital literacy programs, ensuring that rural communities are not excluded from economic and technological transformations. This approach highlights the importance of adapting smart governance strategies to the socioeconomic realities of peripheral regions rather than replicating models designed for metropolitan areas.

Corsica, like the Algarve, has faced challenges in aligning local governance with broader EU smart region strategies. However, its use of digital co-creation platforms to enhance citizen participation provides a compelling example of how digital governance tools can bridge the gap between policymakers and communities. Corsica has also advocated for specialized EU policies that recognize the unique economic and infrastructural constraints of island territories, an approach that the Algarve could adopt to secure targeted funding and governance support for its smart region initiatives.

By examining these peripheral smart regions, it becomes clear that the Algarve must pursue a governance model that prioritizes policy alignment, private-sector engagement, and inclusive digital transformation. The success of the region’s transition will depend on its ability to establish stronger multi-stakeholder governance mechanisms, integrate digital innovation into economic diversification efforts, and ensure equitable access to smart technologies across rural and urban areas.

Successful smart region examples, such as Barcelona and Amsterdam, offer also valuable insights into targeted reforms and stakeholder collaboration. Barcelona has pioneered data-driven governance through open data platforms and real-time analytics, allowing policymakers to monitor urban systems and respond efficiently to challenges. This model of governance ensures transparency and citizen participation, fostering an ecosystem where public trust in smart governance mechanisms is high [48,49]. In contrast, Amsterdam has embraced an adaptive governance framework that facilitates strong collaboration among government agencies, businesses, and civil society. Through its stakeholder engagement platforms, Amsterdam ensures that smart governance initiatives are co-created with diverse actors, integrating public needs into technological innovations.

The success of Barcelona and Amsterdam demonstrates that smart regions must go beyond technological investments; they must also prioritize governance mechanisms that are flexible, inclusive, and data-driven. Adapting these insights to the Algarve means enhancing participatory decision making, promoting open-data governance models, and ensuring that digital transformation strategies are inclusive of all socioeconomic groups.

5. Conclusions

The governance of smart regions in peripheral areas presents unique challenges that demand context-sensitive policy solutions. Unlike metropolitan smart cities with centralized digital frameworks, regions such as the Algarve face fragmented administrative structures, uneven resource distribution, and limited stakeholder engagement. The absence of a unified governance framework, inconsistent municipal policies, and misalignment between public and private priorities have all impeded the region’s progress in implementing smart region initiatives.

The Algarve’s governance relies on the quadruple-helix model—integrating government, academia, businesses, and civil society—but this framework has struggled to foster deep collaboration. University research contributes meaningfully to knowledge creation, yet capacity to transfer and the private-sector engagement in innovation and R&D remains limited, hindering economic diversification and technological growth. Citizen engagement is also weak, especially in rural communities where digital literacy is low and trust in institutions remains fragile. Without inclusive mechanisms, smart region efforts risk exacerbating regional disparities by disproportionately benefiting urban centers.

Addressing these challenges requires adapting lessons from successful smart regions, which illustrate the importance of data-driven governance, stakeholder collaboration, and policy adaptability. Real-time data analytics can enhance decision making, transparency, and accountability, while engagement platforms build trust and foster continuous dialogue between sectors. Adaptive policy frameworks ensure that governance structures remain flexible in the face of rapid technological change.

For the Algarve, translating these models into effective governance involves addressing its tourism dependency, dispersed population, and underutilized innovation capacity. The region’s improving classification in the EU Regional Innovation Scoreboard signals potential that can be harnessed through innovation strategies. However, the Algarve continues to lack mechanisms for continuous stakeholder participation and real-time data governance, limiting proactive policymaking and institutional responsiveness.

Key governance gaps include the underdevelopment of public–private partnerships. Unlike many cases of successful smart regions, where private-sector investment is actively incentivized, the Algarve’s business community remains hesitant to engage in large-scale innovation collaborations. Building trust and offering economic incentives will be essential to foster involvement in these projects.

A major obstacle to the Algarve’s smart region transition lies in the persistent gaps in infrastructure, institutional capacity, and citizen engagement. Many municipalities still lack adequate digital connectivity, while bureaucratic hurdles and limited access to innovation funding restrict the growth of SMEs and tech initiatives. Institutional fragmentation across municipalities leads to inconsistent policies and hinders coordinated planning, and public sector bodies often lack the digital skills to implement advanced technologies. At the same time, the low digital literacy and limited trust in public institutions—especially in particular communities—prevent broader participation in digital governance. Addressing these interlinked challenges requires a more integrated, inclusive, and future-ready governance approach.

Comparative examples from regions such as the Balearic Islands and Crete, which share socioeconomic and geographic traits with the Algarve, offer more relatable governance models than large metropolitan cities that normally represent the more successful cases of smart regions implementation. These regions emphasize regional orchestration, infrastructure resilience, and digital inclusion, highlighting the need for localized strategies that reflect the Algarve’s specific challenges.

Despite advancements in tertiary education, international collaboration, and entrepreneurship, the Algarve still struggles to convert these gains into tangible innovation outputs. Establishing a cohesive governance structure with harmonized territorial policies and alignment with EU smart region goals is essential. Inter-municipal cooperation and policy coherence will be key to fostering innovation across the region.

Initiatives like the Algarve Tech Hub and Algarve Smart Region provide promising platforms for multi-stakeholder collaboration. However, these efforts must be scaled and institutionalized to become central elements of the region’s long-term development strategy. Peripheral regions like the Algarve must resist the temptation to replicate metropolitan solutions wholesale. Instead, they must design governance frameworks that are flexible, locally informed, and equity-oriented.

The Algarve’s experience underscores that governance can act both as an enabler and a bottleneck in regional digital transformation. By prioritizing policy integration, capacity building, and inclusive innovation, the Algarve can emerge as a model for smart governance in non-metropolitan settings. While structural constraints remain, they are not insurmountable. With coherent policies, stronger partnerships, and a commitment to inclusivity, the Algarve is well positioned to lead a smart, sustainable, and people-centered regional transformation to support the emergence of a dynamic, lifestyle-oriented smart region.

Author Contributions

H.P., conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, methodology, software, writing—review and editing, and validation; B.V., conceptualization, investigation, writing—review and editing, and validation; J.E., conceptualization, writing—review and editing, and validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by Portuguese National Funds through the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) under project UIDB/04020/2020. H.P. is funded by FCT (grant agreement ID: CEEC—INST/00052/2021/CP2792/CT0001), and J.E. by FCT (grant agreement ID: 2024.01284.BD).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to Ethics of University of Algarve, available at the following link: https://www.ualg.pt/sites/default/files/documentos/2020-07/codigo-de-etica-da-universidade-do-algarve.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained for all interviews included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request by emailing cinturs@ualg.pt. Access to the data is subject to the approval of the corresponding author of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the KCITAR project (ALG-08-5864-FSE-000004) for making information available for this article. Responsibility for any errors, interpretations, or omissions lies solely with the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ruhlandt, R.W.S. The governance of smart cities: A systematic literature review. Cities 2018, 81, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.; Edelenbos, J.; Gianoli, A. Dynamics in the governance of smart cities: Insights from South Korean smart cities. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2023, 27 (Suppl. 1), 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. Is R&D investment in lagging areas of Europe worthwhile? Theory and empirical evidence. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2001, 80, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, B.; Medeiros, E. The impacts of EU cohesion policy on sustainable tourism: The case of POSEUR in Algarve. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.Y.; Taeihagh, A. Smart city governance in developing countries: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, H.; Uyarra, E.; Fernández-Esquinas, M. University roles in a peripheral Southern European region: Between traditional and ‘engaged’ roles through the provision of knowledge-intensive business services. In Universities and Regional Economic Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, H. Recensão de Os Territórios na Era das Redes: Cultura Digital, Ação Coletiva e Bens Comuns. Cid. Comunidades Territ. 2023, 47, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algarve, S.T.P. Mapeamento do Setor Tecnológico no Algarve. In Relatório para o Projeto KCITAR Algarve; Universidade do Algarve: Faro, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Matern, A.; Binder, J.; Noack, A. Smart regions: Insights from hybridization and peripheralization research. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 2060–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markkula, M.; Kune, H. Making Smart Regions Smarter: Smart Specialization and the Role of Universities in Regional Innovation Ecosystems; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Laranja, M.; Edwards, J.; Pinto, H.; Foray, D. Implementation of Smart Specialization Strategies in Portugal: An Assessment; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, N.J.; Schmidt, J.; Teece, D.J. Ecosystem leadership as a dynamic capability. Long Range Plan. 2023, 56, 102270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.; Autio, E. Innovation Ecosystems in Management: An Organizing Typology. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management. 29 May 2020. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/business/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190224851.001.0001/acrefore-9780190224851-e-203 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Pinto, H. Universities and institutionalization of regional innovation policy in peripheral regions: Insights from the smart specialization in Portugal. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2024, 16, 12659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, E.; Valente, B. Assessing impacts of public policies towards environmental sustainability in an EU region: North of Portugal. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2024, 32, 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The dynamics of innovation: From National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Griffiths, J. Developing intermediate cities. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2021, 13, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, X.; Solheim, M.C. Public-private partnerships in smart cities: A critical survey and research agenda. City Cult. Soc. 2023, 32, 100491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Campbell, D.F.; Grigoroudis, E. Helix trilogy: The triple, quadruple, and quintuple innovation helices from a theory, policy, and practice set of perspectives. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 13, 2272–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, R.J.S. Quadruple Helix co-creation and cities: Behavioral and institutional changes in innovation capacities and cultures. Cities 2025, 157, 105579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancebo, F. Smart city strategies: Time to involve people. Comparing Amsterdam, Barcelona, and Paris. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2020, 13, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. European Innovation Scoreboard 2023; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/779689 (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Savini, F. Self-organization and urban development: Disaggregating the city-region, deconstructing urbanity in Amsterdam. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2016, 40, 1152–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Maier, A. Research for REGI Committee—Islands of the European Union: State of Play and Future Challenges. EPRS: European Parliamentary Research Service. Belgium. 2021. Available online: https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/kt3mhm (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Calzada, I. The techno-politics of data and smart devolution in city-regions: Comparing Glasgow, Bristol, Barcelona, and Bilbao. Systems 2017, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, G.; Brinkman, J.; Wenzler, I. Supporting sustainability through smart infrastructures: The case for the city of Amsterdam. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. 2012, 8, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamowicz, M. The potential for innovative and smart rural development in the peripheral regions of Eastern Poland. Agriculture 2021, 11, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexakis, D.E. Applying factor analysis and the CCME water quality index for assessing groundwater quality of an Aegean Island (Rhodes, Greece). Geosciences 2022, 12, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priano, F.H.; Armas, R.L.; Guerra, C.F. A model for the smart development of island territories. In Proceedings of the 17th International Digital Government Research Conference on Digital Government Research, Shanghai, China, 8–10 June 2016; pp. 465–474. [Google Scholar]

- Savall, N.V. Una aproximación al concepto de innovación social ya su contribución en los estudios de desarrollo territorial///\\\An approach to the concept of social innovation and its contribution to territorial development studies. Terra 2022, 10, 138–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vourdoubas, J. Use of renewable energy sources for energy generation in rural areas in the island of Crete, Greece. Eur. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nationalia. Corsica. Nationalia. Available online: https://www.nationalia.info/profile/12/corsica (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Spicer, E.A.; Swaffield, S.; Moore, K. A landscape and landscape biography approach to assessing the consequences of an environmental policy implementation. Landsc. Res. 2020, 45, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foong, Y.P.; Pidani, R.; Sithira Vadivel, V.; Dongyue, Y. Singapore smart nation: Journey into a new digital landscape for higher education. In Emerging Technologies in Business: Innovation Strategies for Competitive Advantage; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 281–304. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Digital Capacity-Building for Governments. UNESCO. 2021. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/digital-competency-framework (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Schreiner, C. International Case Studies of Smart Cities: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Agencia de Cooperación e Inversión de Medellín. ACI Medellín—Investment and Cooperation Agency of Medellín. Available online: https://acimedellin.org/?lang=en (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Ferrão, J.; Pinto, H.; Caldas, J.M.C.; do Carmo, R.M. Vulnerabilidades Territoriais, Pandemia e Emprego: Uma Análise Exploratória Sobre Perfis Socioeconómicos Municipais e Impactos da COVID-19 em Portugal. RPER 2023, 63, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.J.; Raposo, M.A.; Gomes, C.J.P. The impact of tourism activity on coastal biodiversity: A case study at Praia da Cova Redonda (Algarve—Portugal). Environments 2020, 7, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comissão de Coordenação e Desenvolvimento Regional do Algarve. Estratégia Regional Algarve 2030. 2023. Available online: https://portugal2030.pt/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2023/02/Estrategia-Regional-Algarve-2030.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Aarstad, J.; Kvitastein, O.A. Enterprise R&D investments, product innovation, and the regional industry structure. Reg. Stud. 2020, 54, 366–376. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00343404.2019.1624712 (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Gonçalves, A.R.; Ramos, C.M.; Viegas, C. Mediterranean Diet and Tourism Innovation, Experiences, and Sustainability: The HoST Lab Case Study. In Handbook of Research on Innovation, Differentiation, and New Technologies in Tourism, Hotels, and Food Service; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 176–194. Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/gateway/chapter/329375 (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Bianchi, C. Fostering sustainable community outcomes through policy networks: A dynamic performance governance approach. In Handbook of Collaborative Public Management; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 349–372. [Google Scholar]

- Rochet, C.; Belemlih, A. Social emergence, cornerstone of smart city governance as a complex citizen-centric system. In Handbook of Smart Cities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jager, N.W.; Newig, J.; Challies, E.; Kochskämper, E. Pathways to implementation: Evidence on how participation in environmental governance impacts on environmental outcomes. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2020, 30, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, J. The digital transformation of logistics: A review about technologies and their implementation status. In The Digital Transformation of Logistics; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 361–403. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, F.; Santos, J.D. The effects of COVID-19 on job security and unemployment in Portugal. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2020, 40, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeley, G. Governing ourselves: Citizen participation and governance in Barcelona and Manchester. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2010, 34, 130–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remmele, B. The ATELIER project: Citizen-driven Positive Energy Districts in Amsterdam, Bilbao, and beyond. Int. Verkehrswesen 2020, 72, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).