Abstract

This paper systematically reviews scientific papers to understand the primary forms of HI, why they arise, and how they affect the urban landscape. It addresses the question, “What are the key trends, drivers, and impacts of Housing Informality (HI), and what methods researchers use to study the latter?”. Previous research addressed the trends, drivers, impacts, and methods individually, failing to adopt a holistic perspective that could clarify HI as a core scientific concept distinct from informal housing. Accordingly, this systematic literature review (SLR) explores 541 scientific peer-reviewed publications from Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. By utilizing a PRISMA framework, we reduced the number of documents to 27, which we thoroughly analyzed. The results highlight five main trends of HI around the globe: unauthorized modifications, informal market dynamics, Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), squatting, and unusual housing. These trends are induced by several economic and sociocultural drivers that address the gap between regulations and governance from one side and lived realities from another, resulting in economic, social, legal, health, and urban impacts.

1. Introduction

Housing is more than a utility; it forms the basis for social inclusion and economic activity, which are vital for well-being [1,2,3]. It is a non-negotiable element of social security [4]. Accordingly, housing provision is still at the heart of modern human rights talk and has become a continuous part of international policy talks [5]. Both scholars and practitioners have acknowledged the strong relational position of safe and stable housing as essential to individual and community resilience [6], demarcating access to economic mobility pathways, public health outcomes, and socio-economic equity more broadly realized. Nonetheless, the global rapid urbanization processes come with unusual housing hurdles [7,8] and antagonisms with soaring prices, whilst a dearth of formal housing supply results in widening social disparities. Thus, exponential urban population growth outpaces formal housing stock availability [9] and stimulates land use changes, driving out-migration and sometimes outright expelling existing residents from their homes [10].

Urban housing systems must be elastic, accommodating various needs as they emerge [11]. In this context, the terrain of housing informalities (HI) is prominent—they are seen as both a sign of strain in urban housing gaps and an undermining of formal governance forces, and simultaneously a place from where interesting responses to unmet demands emerge. The flexibility, adaptability, and resourcefulness of informal housing practices—previously condoned as a “necessary evil”—are starting to be recognized for their ability to fill the gaps in formal housing systems [12]. However, scholarly discussion needs to differentiate between informal housing, which is typically associated with entire settlements developed without formal ownership or planning permissions [13], and housing informalities (HI), a completely distinct classification that covers various unregulated practices within formally recognized urban settings [14].

Informal housing is commonly linked to the Global South, where rapid urbanization and inadequate planning give rise to substantial informal settlements [15,16]. Such settlements are built beyond the purview of the law but eventually grow into established towns [17]. By contrast, housing informalities—the focus of this study—go beyond the zones of ownership and legality. This concerns unauthorized alterations and the informal use of the property in built-up areas otherwise governed by formal regulations. Crucially, these practices not only happen in the Global South, but are also more and more prevalent in high-income, highly-regulated cities. Cities in the Global North, including London, New York, and Sydney, have high housing affordability issues [18,19] where Accessory Dwelling Units (ADU) and sub-divided units (SDU) are emerging as semi-formal responses to stock deficiency, highlighting the housing informalities practices occurring across changing socio-economic landscapes [20,21].

This differentiation between informal housing and housing informalities (HI) is crucial for analyzing the changing landscape of urban informality [13,14]. They are tucked inside existing regulatory frameworks, but they remain non-conformist in a couple of dimensions, or they overexploit legal bounds to respond to the evolving needs of their dwellers [22,23]. Such informalities frequently result from regulatory blockades, economic outcasting, and sociocultural imperatives, making them a complicated and multi-pronged issue [24]. While informal settlements are commonly perceived as housing poverty and marginalized populations, HI can also result from urban densification [25], inward migration, and the failure of formal housing markets to produce reasonably priced and resilient forms of homes [26]. This complexity demands a deeper investigation of the root causes of HI, the methods used to analyze them, and the multiplicity of impacts they have on urban communities and landscapes.

The significance of research in HI is that it can take us beyond the formal housing and planning paradigms to open up spaces for re-imagining new possibilities towards urban resilience, adaptable housing, etc. Much of the work is on informal settlements. Still, this research extends its concerns into legal and planned urban landscapes regarding housing informalities—precisely where regulatory frameworks do not capture the nuances of contemporary transforming home needs [27]. This will help inform us on opportunities to explore how unauthorized alterations, uses of shared housing, and temporary structures operate within functionally informal contexts like those we identified in relatively high- and low-income contexts—thus providing a telling illustration of the creative strategies through which people and communities find their way in negotiating for space, legality, and survival inside existing formal housing markets.

This review is driven by the recognition that despite extensive research into discrete aspects of housing informality—from informal housing and unauthorized modifications to squatting—the body of knowledge is still disjointed. Earlier studies have tended to isolate these topics rather than analyze the combined effects of trends, research strategies, underlying causes, and consequences [24,26]. Here, we aim to close that gap by use of the following:

- Concept distinction. This explanation delineates informal housing, usually linked with complete settlements operating beyond formal legal frameworks, from housing informalities, which denote particular unregulated practices in regulated urban areas;

- Integrating multidimensional insights. This systematically synthesizes diverse aspects, such as market dynamics, regulatory challenges, socio-cultural drivers, and methodological approaches that previous research has treated separately;

- Emphasizing worldwide differences. The paper demonstrates that housing informalities extend beyond the Global South, emerging more frequently in high-income, tightly regulated urban centers and enriching the debate on housing issues;

- Informing decision-making in policy and practice. The review’s integration of quantitative and qualitative perspectives creates a robust framework for guiding future urban planning, policy strategies, and academic debates on housing and informality.

This paper uses a systematic literature review (SLR) to explore and synthesize existing knowledge of housing informalities (HI). Based on an in-depth literature analysis, including key scholarly databases, we summarize trends, methods, and drivers of HI and impacts across sectors to comprehensively map current research on HI within urban settings. By doing so, we reveal some significant methodological lacunae in the literature, and suggest alternative directions for future research that can illuminate more comprehensively the socio-spatial (in)formality and its economic effects on housing informalities. Such quantitative and qualitative bridge-building contributes to broader debates on urban housing and informality, valuing HI not simply as a byproduct of socio-economic exclusion but as an essential and adaptive part of contemporary urban ecosystems. This research aims to answer a central question: “What are the key trends, drivers, and impacts of Housing Informality (HI), and what methods are used by researchers to study the latter?”. This SLR thus incrementally informs our understanding of how formal governance and urban planning practices intertwine from informal housing dynamics to housing informalities practices. The study is structured in five sections. After this introduction, which depicts housing informalities practices and their relation to rapid global urban growth dynamics, Section 2 details the SLR steps through the PRISMA framework. Section three analytically presents both the quantitative and qualitative results. Section four extends the discussion to urban housing and development at large, while section five wraps up the study with a summary and key insights.

2. Materials and Methods

Following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines [28], this study applies a systematic literature review (SLR) methodology. Unlike primary research methods like field surveys or interviews, systematic reviews are a structured framework for analyzing previous studies. PRISMA enhances transparency, minimizes bias, and ensures a rigorous selection process in housing informality research. We extracted data from significant sources when collecting research papers, including Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. We limited ourselves to those three databases for their journals’ scientific rigor and reputation. Moreover, we found that those databases cover the best of all the fields concerning housing informalities. Other sources were either repetitive or did not yield considerable results. To extract records from Google Scholar, for commodity reasons, we used Harzing’s Publish or Perish free software (version: 8.10.4612.8838) to get all the papers corresponding to our search strings at once. We used Boolean operators to form our search queries using the study keywords. Before diving into the analysis, we subjected the gathered data to a stringent preparation process. Raw records were manually scrutinized and cleaned to remove errors, duplicated entries, and irrelevant variables. We standardized data formats across all sources, ensuring uniformity and quality, which paved the way for reliable quantitative and qualitative analyses. Data extraction from our selected databases took place on May 10, 2024.

Data collection process

Inclusion criteria:

Included keywords—Housing informality(ies), informality(ies) of housing and, informality(ies) in housing;

Language—Only papers published in English or French that are familiar to the authors and comprise most published materials within the scope of HI were considered.

Exclusion criteria:

Excluded keywords—informal housing, informal settlements, and slums. Publications mainly focus on informal settlements or slums;

Language—The exclusion criteria concern the use of languages other than English and French;

Papers published in conferences—Conference papers were also intentionally excluded to guarantee reliable and trustworthy references. All selected papers are original research or review publications that underwent peer review and are indexed in at least one of our chosen search engines and databases.

Screening: Three-step verification

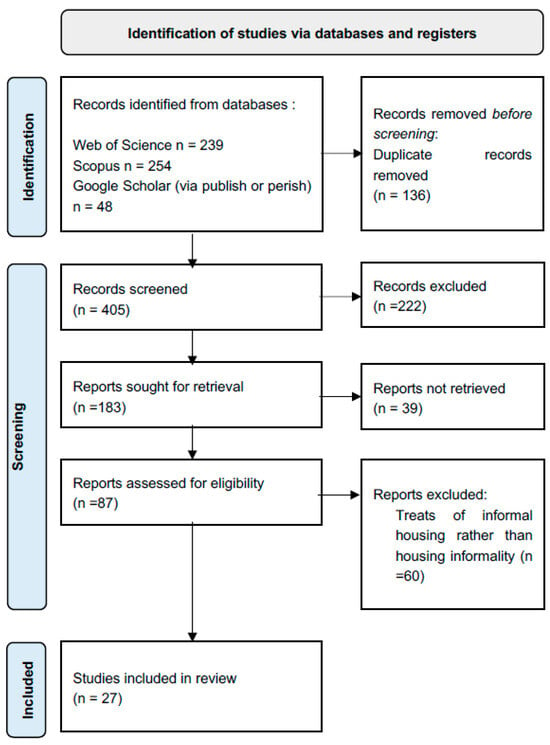

After the first screening, we implemented a three-step verification that included a review of the title, the abstract, and the content to decide whether the papers were relevant. Reviewing titles and abstracts to judge relevance, a reviewer first screened the records. Afterward, a second reviewer independently re-evaluated the selection to confirm the decisions made. This independent verification process aimed to minimize bias, using Microsoft Excel for duplicate removal. As the PRISMA flow diagram expresses (Figure 1), this all-encompassing process ensures the papers selected to study for HIs are the most relevant.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram of the study.

We adopted a systematic method to evaluate bias risk in the studies included. For this review, we designed a tailored checklist that examined key elements in each study. The checklist aimed to ensure equitable data selection, confirm the clarity and consistency of outcome measures, assess the reports’ comprehensiveness, and uncover potential conflicts of interest. Two independent reviewers conducted these evaluations to minimize subjective influence and ensure an objective, transparent assessment. We documented intervention characteristics and compared them with the predefined synthesis groups to determine eligible studies. Data for synthesis were prepared with precision in Microsoft Excel software (for Mac, version 16.72), using the number 1 to denote the availability of the items and 0 for their unavailability. We synchronized study measurements to develop a standardized dataset essential for meaningful comparisons and data merging.

Furthermore, we compiled the results into detailed tables and visual charts using Microsoft Excel software and online Google Sheets. Our approach involved comparing subgroups categorized by relevant study attributes and contextual factors, namely, scientific fields, interdisciplinary areas, research methods, geographical region, trends, drivers, and impacts, once again using the number 1 for the availability of the items and 0 for their unavailability, to gain insights into study variability. This strategy was aimed at investigating potential differences in the study findings. We also conducted sensitivity analyses to verify the stability of our overall results, confirming that our conclusions held even with the exclusion of specific studies or data elements. We carefully scrutinized the risk of bias from missing results by reviewing the published outcomes and double-checking the data extraction process, thereby reducing potential distortions from reporting biases. Ultimately, we assessed the overall certainty of the evidence through a systematic evaluation of study limitations, consistency, and precision, which provided a reliable measure of our confidence in the combined results.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

We scanned three essential academic databases to obtain different HI literature sources—Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, and Google Scholar. Up to 10 May 2024, we identified 541 publications in total (WoS n = 239; Scopus n = 254 and GS n = 48). To ensure each paper was original, our team created a Microsoft Excel process to identify and delete duplicates. Then, 136 repetitions were removed from the 541 papers returned; 405 unique entries remained to form an accurate dataset. Title and abstract evaluations were performed in the screening step to verify whether the investigations therein were related to the primary focus of this study, namely, that HI occurs within legally acknowledged systems. Then, 183 publications were finally selected after a painstaking selection process, focusing on their abstracts, in anticipation of comparing each research paper primarily concentrating on HI rather than having broader conceptions like informal housing, informal settlements, slums, or shantytowns generally. Accordingly, 87 articles were retained following a careful and demanding selection process for further study. Each of the 87 articles was thoroughly evaluated during the eligibility test to ensure they met the inclusion criteria. This phase involved corroboration to ensure that the materials focused on housing irregularities as stipulated in legally recognized frameworks. Sixty articles were rejected because they did not meet the requirements, especially those focused on informal settlements or slums. Ultimately, 27 publications meeting all the inclusion criteria were selected for review (see Table 1). These articles were selected based on their focus on housing irregularities and compliance with the established criteria, thus ensuring that high-quality, relevant literature will be reviewed. The table below presents 27 publications arranged chronologically—from the oldest to the most recent. Each entry has been assigned a code name (Paper n) to facilitate a systematic analysis of the key trends, methods, drivers, and impacts associated with urban housing informality. Two reviewers employed a standardized data extraction form to gather information from each report. They documented key study details such as the main fields, interdisciplinary areas, research methods, geographical region, trends, drivers, and impacts.

Table 1.

List of the 27 selected records.

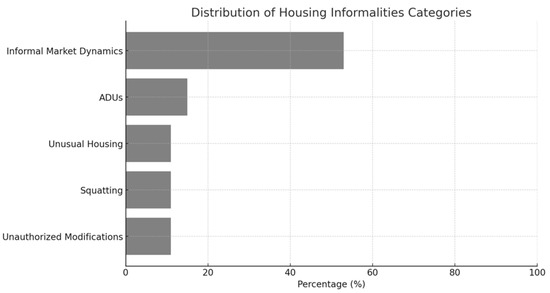

3.1.1. Key Trends in Housing Informalities

Housing informalities (HI) can be classified into five key trends, each signifying a different response to regulatory and economic pressures. The first trend, Informal Market Dynamics, covers extra-legal housing practices such as informal housing tenure based on verbal agreements; migrants’ housing dynamics, where legal obstacles lead to informal living situations; sub-divided units (SDUs), which result from partitioning legally recognized dwellings into unregistered rentals; shared housing without formal lease contracts; online rental platforms that enable short-term rentals outside regulatory oversight; and informal financing, including private loans or savings groups that sidestep traditional mortgages. Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), the second trend, are secondary residential units like backyard flats or garage conversions. While some are legal, many remain informal due to zoning restrictions. The third trend, unauthorized modifications, involves unapproved structural changes—such as adding floors or subdividing interiors—to meet space or income needs, often clashing with urban policies. Unusual housing is a movement that converts atypical structures, like container homes and boat houses, into residential spaces. Financial constraints, regulatory barriers, or personal preferences drive this trend.

On the other hand, squatting—the illegal occupation of land or buildings—has become a way to address housing shortages and challenge property laws in high-cost markets. These trends are part of housing informalities (HI), encompassing Informal Market Dynamics, Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), unauthorized modifications, and informal housing tenure. Migrants’ housing dynamics, sub-divided units (SDUs), shared housing, online rental platforms, and informal financing are also central to these trends.

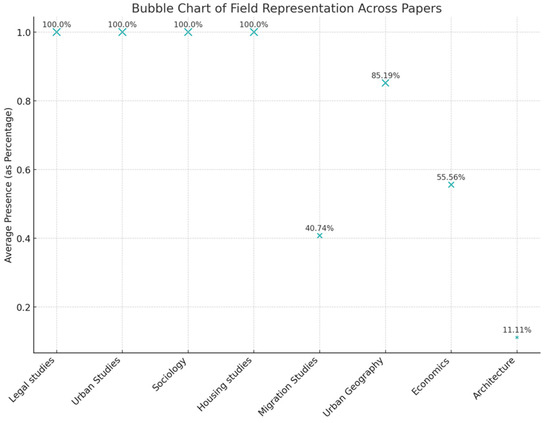

3.1.2. Subject Areas: Interdisciplinary Analysis

As illustrated in the bubble chart (Figure 2), the distribution and emphasis of research into housing informality among various academic disciplines set forth the disciplinary perspectives necessary for investigating HI, juxtaposing the proportion of research articles in each area. As the figure demonstrates, Legal Studies, Urban Studies, Sociology, and Housing Studies account for 100% of the studies selected. This strong presence reflects the importance of these fields in understanding and analyzing housing informalities (HI). Together, they highlight HI’s complex and multi-dimensional nature.

Figure 2.

Bubble chart of subject areas of the papers that treat HI.

Legal Studies—A recurring field throughout the reviewed articles, demonstrating the legal dimensions inherent in many of the corresponding HI. Since HI typically exists outside the formal boundaries established by law or even in direct breach of it, investigating such phenomena usually entails, to some extent, examining legal systems, rules, and illegality itself. Legal Studies give us key perspectives on how these informal practices are regulated, fought over, or ignored in different jurisdictions, and underline the complexity of this relationship between law and housing.

Urban Studies—These are key to the analysis of HI, as these practices have been predominantly urban and interact with the major socio-economic forces reshaping urban forms. Indeed, as cities worldwide are increasingly going through rapid transformations, providing adequate housing, sustainable land use, and urban planning practices became essential issues, thereby rendering Urban Studies a crucial subject in understanding how HI gets established, adjusts, and influences the emergent qualities of urban landscapes. The universality of this subject in the literature illustrates that HI must be placed within broader urban development, governance, and sustainability debates.

Sociology—Sociology’s prominent presence in the reviewed papers signals its critical contribution to understanding how HI are socially structured and, conversely, structure social relations and hierarchies. Using a sociological perspective, we can examine how communities manage informal settings, the social norms that shape housing practices outside formal regulations with an emphasis on family values, and how both collective and individual decision-making contribute to HI’s lasting endurance.

Housing Studies—Housing Studies in all the papers considered for review underscore the natural and direct relationship with HI as a subfield within housing. Housing Studies examine how housing markets, policies, and functions interact across different parts of the world. This is essential to untangling how HI is situated within a larger context of defined urban systems and dynamics.

It investigates the changes in housing provision and the practices of living generated when formal housing responses no longer suffice, thereby revealing how HIs operate as reactions to—but also catalysts for transformation within—housing landscapes.

Urban geography appears in 85.19% of the reviewed papers, demonstrating its importance for the spatial analysis of HI and highlighting that locality is a prime factor when interpreting such phenomena. The geography in which practices are embedded profoundly impacts how HI can be realized due to substantial differences between different urban contexts. The attention to urban geography helps underscore how, even if certain informal practices may seem similar, the particular layout of city space, infrastructural requirements, and socio-spatial dynamics in which they occur will offer markedly different attributes and implications.

Economics featured in 55.56% of the studies, suggesting economic factors were significant reasons for housing informality. Economic analyses were peppered throughout more than half of the studies reviewed, indicating the centrality of housing affordability, income inequality, and market failures in catalyzing such conditions. Economic analysis sheds some light on why a community will use informal settlement, as the lack of formal housing options often forces this.

Migration Studies—More than a third of the reviewed papers (40.74%) focused on Migration Studies, suggesting a substantial overlap between migration itself and HI as an essential dimension of modern urban population mobility. The field of study represents a necessary link between migration patterns, which are frequently driven by socio-economic disparities and the lack of jobs/poverty, along with a quest for higher standards of living, on the one hand, and informal housing processes on the other. Migrants, especially those on the economic margin or uncertain of their legal status, are often forced into informal housing arrangements as they go through insecure urban areas. These crossroads highlight the dual potential of HI as a survival strategy and in response to broader socio-economic challenges confronting the migrant population.

Architecture—Surprisingly, only 11.1% of reviewed papers are about housing informality from an architectural perspective, which is paradoxical, since housing informality is related to architectural modifications in both the tangible and intangible realms. From the soft, imperceptible practices that suggest the use of changes to and perceptions of built spaces to direct physical transformations, housing informality is always tied in with architectural form and function. As such, these studies’ failures to examine the architectural motives of HI prompt a pressing interrogation of how architectural practices produce (or inhibit) informal housing dynamics despite being at their core.

3.1.3. Regional Trends: A Comparative Analysis

To present a more rounded analysis of housing informalities (HI), it is necessary to unpack the Global North and South trends further. The global trend of these practices points to the phenomenon’s universality, and highlights regional differences that influence informalities in housing.

Informal Market Dynamics

The bar chart above (Figure 3) shows that the most common studies were on Informal Market Dynamics (accounting for about 53% of total publications). This regards the dominance of market-oriented forces at the center of informalities in housing practices on a global scale, as people and societies strive to develop innovative alternative responses concerning housing beyond formal, regulated markets. A detailed exploration of the subtrends within Informal Market Dynamics illustrates how multifaceted this category is. While the largest subtrend associated with housing informality appeared to be geared toward discussions on informal housing tenure (71%), this underscores that issues with securing legal and stable accommodation are not just a phenomenon for specific countries in the Global South, but arise around the world [47]. In many cases, especially in rapidly urbanizing countries that struggle to accommodate socially marginalized groups, informal tenure systems play a significant role in offering shelter that the formal market is not able to provide [35,44,48]. It shows how the failure to secure formal housing leads many to act informally. The second axis is Migrants’ Housing Dynamics (43%); migrants—who may be internal or external—repeatedly find themselves excluded from the formal housing systems by a web of legal, economic, and social obstacles. In the case of such amenities, potential migrants to the city may turn their attention to using urban housing markets (e.g., subletting or shared housing) as informal strategies in a densified built environment, which can be seen in cities like Hong Kong [36,41] and New York City [20].

Figure 3.

Bar chart of the global trends.

Furthermore, other adaptive strategies—particularly the use of sub-divided units (SDU) (14%)—are more prevalent in cities like Los Angeles and Sydney [22,42]. SDUs generally arise as under-the-table additions to existing homes, creating opportunities for flexible, affordable living in regions with sky-high housing prices [49]. Likewise, shared housing—representing 14% of the Informal Market Dynamics—is especially prominent in cities like London [18], where rising housing prices force residents to live together. SDU and shared housing also identify the functionality of how crushing competitive housing costs pushes marginalized residents to live informally off the books. Finally, the rise of online rental platforms (7%) in Informal Market Dynamics has emerged as a disruptive subtend in the latest developments. In cities like Sydney, platforms such as Gumtree have facilitated the formalization of housing through rentals that fall outside formal housing regulations by renting by item (bed or individual room) instead of dwelling [42], putting intense pressure on local supplies. Lastly, informal financing (7%) indicates the broader economic challenges faced in markets like Nigeria [6], where access to formal financial systems is limited, leading residents to utilize community-based finance saving or borrowing for housing requirements from informal lenders.

Adaptive Practices

ADU and Unauthorized Modifications

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADU), the second most common type of semi-formal homes in the dataset, account for about 15% of the reviewed papers. The push for ADU is one of the few bright spots in alleviating the housing shortages plaguing high-demand urban areas. Informally built backyards offer a flexible approach to meeting the growing need for affordable housing. They allow property owners to create living spaces without following conventional housing regulations. ADUs are a long-standing trend in some countries, such as Australia [19] and South Africa [24], responding to housing pressures and evading formal housing regulations. Although less studied (11%), unauthorized modifications are a similarly widespread form of adaptation, especially in the Global South [50,51]. This phenomenon is prominent where existing housing provisions do not correspond to the actual needs of the residents. Due to those diversified needs, they modify their formal houses at their own will without permission, as in the case of Turkey [33] and Morocco [21], for instance. In the construction arena, illegal changes in land use represent a continual contest between formal rules and regulations on one side, and urban life as city-dwellers live it on the other.

Alternative Housing

Unusual Housing and Squatting

On a global scale, the proportions of both unusual housing and squatting in the dataset are relatively high, at 11%; however, they remain marginalized from current discourses on housing informalities, reflecting their shallower academic coverage. Unusual housing is a phenomenon currently flourishing in certain zones across the planet, such as New Zealand and Oxford [45], characterized by various innovative and non-standard residential solutions that primarily differ from traditional housing standards. Such alternative strategies, including mobile dwelling camps, container housing, and boats, respond to the limitations of an increasingly restrictive local housing market and a growing demand for adaptable and affordable alternatives [4]. These examples illustrate how residents find and fit within crevices and non-regulated spaces when pursuing adequate housing rights. By comparison, squatting (a regular occurrence in places like Milan, Beijing, and former Eastern Germany) is a symbol of broader social exclusion and the housing crisis [52,53]. Squatting is seen in urban areas when impoverished people live in abandoned buildings by permission, to operate them, or otherwise—often as soon as a housing inventory and affordability crisis heightens the pressure on residential space [54,55]. This has a peculiar salience in the Global North, where political movements campaigning for housing rights are constrained severely by markets. In these areas, squatting begins to take the form of a practical approach to self-provision of housing, and also as a path through which to subvert official protocols—not just around what is legal or illegal, but about how the objectives of the right-to-housing and the urban process itself can be redirected.

Comparative insights: Global North vs. Global South

Despite vast geographical, economic, and cultural differences between the Global North and Global South, a cross-national comparison shows that housing informalities are born of shared necessity within an ever-changing economy, regulatory frameworks, and evolving social needs. However, not all adaptations are created equal. In the Global South, they are a response to either the absence or the failure of formal systems that cater to increasing urban populations [56]. This is where you find Informal Housing Tenure and unauthorized modifications—residents actively seeking to address challenges within formal housing systems. For their part, the informalities of the Global North—shared housing, ADU— are much more about navigating high-cost and over-regulated housing markets [18,19,22]. Destitute people hindered by the high cost of formal housing systems have instead improvised their solutions. The most prevailing trend, Informal Market Dynamics—seen equally in the Global North and Global South—reveals how informal housing practices emerge, catalyzed by market failures and affordability issues. Nevertheless, the shape these practices adopt (even if they do so as an ADU in the Global North or an unauthorized modification in the South) manifests the particular socio-economic and regulatory contexts of urban informality for housing. By considering the interrelations of housing informalities in their entirety, such a wide-angle approach enhances our understanding of the intricate strands that weave them together and, thus, how we might best address them via more informed policy interventions, as well as urban planning strategies relevant to both regional and global contexts.

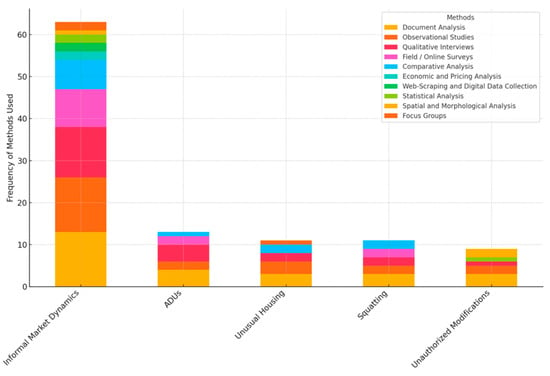

3.1.4. Research Methods: A Comprehensive Overview

The multifaceted nature of the HI is such that addressing them necessitates using a combination of research tools. The methodological approaches found in this analysis highlight the dynamism involved in housing informality trends and the instruments used to study them. Figure 4, a stacked bar chart of primary research methods used across the trends covered in the dataset of this SLR, is given below.

Figure 4.

Stacked bar chart of method frequency according to each trend.

The co-occurrences shown in Figure 4 are empirical patterns drawn from the literature without evidence of causation. These patterns can be examined through various theoretical viewpoints to investigate how small-scale informality integrates with urban systems. For example, adaptive governance theories [57] emphasize how households and communities create innovative housing solutions when formal regulations are too restrictive or costly. Incremental urbanism [58] explores the gradual modifications—like unauthorized extensions—that residents implement to adjust their homes to changing family or economic circumstances. Furthermore, theories on informal housing [59,60] emphasize the interplay between formal regulations and socio-cultural norms, illustrating how activities in the “grey zone” emerge due to shortcomings in official housing policies. By connecting these phenomena to ongoing debates, we tie empirical observations—such as the significance of Informal Market Dynamics or the understudied practice of squatting—to broader understandings of how everyday agency, regulatory constraints, and market inefficiencies influence urban housing landscapes.

Informal Market Dynamics

Informal Market Dynamics is the most frequently studied and the most varied in terms of methodologies applied, making up the most significant portion of methodological applications across all datasets. Document analysis and qualitative interviews are essential for this trend, as they contain many historical and legal records pertinent to the study, as well as the lived experience of stakeholders within informal housing markets. All these methods are critical in unpacking the regulatory and socio-economic issues underpinning market-driven housing solutions in informal landscapes. Field/online surveys and economic and pricing analysis are the principal methods used to explore Informal Market Dynamics, which implies a quest for reliable data to identify economic forces underlying informal housing practices. Although much less commonly used, there is an emerging potential to use web-scraped live data from online platforms (e.g., Gumtree). This could offer an opportunity to get some insight into informal rental arrangements that fall under the radar of formal regulation. Accordingly, our methodological landscape within this trend highlights a holistic perspective on informal market dynamics in Global North and South contexts.

Adaptive Practices: ADUs and Unauthorized Modifications

Researchers take a relatively balanced approach in investigating Accessory Dwelling Units (ADU) and unauthorized modifications, with an inclination toward qualitative methods. Significantly, this section highlights the prominence of field/online surveys and, by implication, of direct engagement with property owners and residents involved in creating or adapting these informal spaces in response to formal housing shortages (field/online surveys; qualitative interviews). Spatial and morphological analysis have mainly been overlooked in the study of unauthorized modifications, a shortcoming that highlights a unique challenge with these interventions. Because common housing additions often result in substantial morphological changes, this oversight opens a promising avenue for research into unauthorized housing practices in regions like Morocco [21] and Turkey [33], where informal alterations abound. The rarely used Economic and Pricing Analysis of ADUs points to a more detailed examination of the economic costs associated with semi-formal housing outside these immediate neighborhoods, which could provide land markets in urban centers. By incorporating such analyses and data, researchers can more effectively quantify the economic scope of ADUs and grasp their trade-offs, most notably in high-demand urban housing markets like Los Angeles, Sydney, etc.

Alternative Housing: Unusual Housing and Squatting

The researchers in our reviewed papers mostly use qualitative approaches to study unusual housing and squatting through document analysis and qualitative interviews. Comparative analysis and observational studies are also noticeable in both trends. This demonstrates an interest in comparative approaches on global scales to understand real-time adaptations of urban spaces. Yet, much of the research employed spatial and morphological analyses despite the effects of spatial change. This lack of consideration provides an area where future research could analyze how these informal practices affect the urban fabric, particularly in densified environments.

Furthermore, none of these trends feature economic and pricing analysis, suggesting that the broader market impacts (if any) on unusual housing and squatting are not being duly researched. Including economic data would help drill down into the affordability pressures driving people toward these alternative housing options, especially in expensive urban areas in both the Global North and South. The more frequent application of these under-used techniques would significantly improve our knowledge of these housing informality trends’ socio-economic and spatiotemporal aspects.

The various methodologies applied across the trends in housing informality give an all-encompassing picture of the dynamics (socio-economic, legal, and spatial) at play. Nevertheless, the analysis exposes notable gaps in some trends (e.g., unauthorized modifications, unusual housing/squatting) mainly due to the less common usage of spatial and morphological analysis and Economic and Pricing Analysis. Focusing on these gaps also enables future researchers to more clearly explore how housing informalities practices mold to urban contexts and meaningfully stem from economic factors. Through expanding the methodological toolkit, researchers can bring an increasingly multi-faceted view to the study of housing informality, which is critical for evidence-informed policy and urban planning in Global North and South contexts.

3.2. Qualitative Analysis

Quantitative analyses are essential in understanding the statistical prevalence and distribution of trends within Housing Informalities (HI). Moreover, qualitative analysis allows for a more detailed exploration and new insights into the drivers, impacts, and/or context surrounding the HI phenomena. We also found that qualitative research can provide transdisciplinary insights into some of the intricate socio-economic, cultural, and regulatory dynamics surrounding HI, which quantitative data alone may not capture in all dimensions. Transitioning from the numerical characterization of trends to a thematic evaluation, in this part, we analyze the motivators, contexts, and macro socio-political mechanisms that facilitate HI across different geographies. This more nuanced approach offers more profound insights into HI, delivering significant gains in understanding how people and communities live in and through the housing informality landscapes. By interrogating these drivers, we hope to shed light on the multifaceted web of processes that underpin the longevity and changes of housing informality. In this context, we specifically examine the differences in these drivers across individual states. A study component aims to highlight the variations of these drivers and how they are manifested in different regions or communities.

3.2.1. Drivers: Thematic Assessment

Economic Drivers: Foundational Determinants Across Geographies

Among the various influences on housing informality, economic factors are the most widespread motivators of market-determined processes and informal practices across geographies. This is particularly notable in Informality Market Dynamics, ADU, and squatting/unauthorized modifications. Economic precarity and income inequality dominate housing affordability issues, which, in most cases, push individuals and households towards non-formal housing arrangements. The informal sector allows individuals who are otherwise boxed out by the formal housing sectors (due to lack of proper financial standing) to negotiate through these constraints. Of course, economic drivers do not act in a vacuum. They coincide with supply-side limitations, especially in high-demand urban locations where public housing is either absent or costly. For example, the emergence of Informal Market Dynamics within fast-growing urbanizing economies illustrates how market forces can lead to increased housing informality practices. These practices occur in the grey zones of economies, which are not addressed by formal regulations and offer a space for populations otherwise excluded from traditional housing markets. Likewise, Accessory Dwelling Units (ADU), a way to retrofit houses for housing shortages under informal economic arrangements, show where economic imperatives and legal circumvention intersect in highly regulated Global North housing markets.

Social and Cultural Drivers: Contextual Nuances in Housing Informality

A second layer of complexity arises with social and cultural determinants of informal housing. They talk about the patterns of behaviors at the community level, shared norms, and individual household strategies that work within, or are often are controversial in, the formal regulatory framework. This can especially be seen in phenomena like unauthorized modifications and squatting. People adapt what they are given into something that works for their community. Socio-cultural imperatives are a primary driver of extra-legal alterations in the case of unauthorized modifications, which typically occur through the renovation of formal housing units to accommodate multi-generational families living in or rented the property. Such adaptations are common in areas like Turkey and Morocco [21,33], where the presence of extended families and traditional cultural practices impact housing. In this light, squatting is understood as not only a reaction to housing exclusion on the part of individuals, but also more broadly as an action of city-wide resistance, as is the case in Milan [31] and East Berlin [34].

Vacant properties are targeted by squatters as a protest against unaffordable housing markets, exposing a broader contestation between citizens and urban governance frameworks. The Villa Verde housing project in Constitución, Chile, exemplifies how formal and informal practices can merge creatively. The incremental housing model in Villa Verde is a system wherein residents can finish their homes through informal building, starting with one slab and two perimeter walls, with the formal components pre-designed [38]. The project is a robust case in which informal strategies, enabled by the participatory and adaptable environment, give rise to self-regulating yet robust habitat alternatives. The participation in turn empowers the residents, making them content and at home, and also provides a means for informal practices with few aesthetic constraints determining architectural alignment. One of the reasons the Villa Verde project is so important is that it reveals how informal buildings can be incorporated into formal systems, providing a more versatile housing solution. This model is anchored in a participatory approach. The authors repeatedly call upon residents to attend workshops where they learn how to upgrade their homes [38], thereby setting up a structured but adaptable informal construction process. Residents also participate in the participatory process, creating a sense of community and developing local responsibility through an architectural coherence implementation strategy. The project of the architect Alejandro Aravena pointed out how informal construction can be combined with a formal system, opening the approach up for a more significant middle-class population.

Regulatory and Institutional Factors: Enablers and Constraints

The variable interplay of regulatory and institutional conditions is one of the most relevant topics across the housing informalities spectrum, from end to end. Human encounters with the built environment in a rule-governed world of formal housing regulations are, characteristically and crucially, spatially contingent on access to regulatory apparatus. Informal practices fester when there is little or sporadic institutional oversight. In both the Global North and Global South, regulatory frameworks lag behind in adjusting to urbanization [61], and tend to exacerbate exclusionary housing markets. Weak regulatory environments lead to unregulated rentals, sub-divided units, or informal financing [27].

Nevertheless, online platforms such as Gumtree in Sydney may contribute to normalizing extra-legalized and informal rental arrangements, enhancing opportunities for speculative behaviors at the margins of more conventional housing market forms [42]. However, in the context of unauthorized modifications, the tight planning controls may also encourage homeowners to go around the formal system and carry out unpermitted changes of use in their homes. In addition to this, in some locations like New Zealand and Oxford, prime examples of unusual housing (such as container homes or dwellings on wheels) can appear as creative responses to the restrictions of regulation themselves [45], especially in markets where formal housing responses are falling behind widespread accumulation needs. As a result, the flexibility of housing informality solutions has become essential for many city dwellers who are not able to afford higher housing costs [6,14,20].

Demographic and Migration Dynamics: Migration as a Catalyst

Migration (internal and international) usually intersects with the informality of housing, given that migrant populations frequently lack access to formal housing markets due to legal, financial, or social restrictions. It is the archetype of informal housing for displaced or economically disadvantaged migrant workers, used in this case as a survival strategy (squatting and Informal Market Dynamics). The informal nature of housing stock in urban areas is further compounded by undocumented or precarious migrant populations, stimulating demand for affordable and adaptable options. This is the case for the SDU or shared houses that many migrants are turning to in cities like New York [20] and Hong Kong [36] to find alternative urban living accommodation.

Adaptability and Flexibility Needs: Drivers of Alternative Housing Forms

Adaptability and flexibility are other unique drivers strongly related to unusual housing and unauthorized modifications. The requirements for such models are grounded in economic realities and underlying consumer preferences for housing solutions that can change with life stages. Trends in unusual housing, like alternative containers or mobile dwelling homes, answer the need for adaptive-type solutions for different situations when traditional modes of housing are difficult or impossible to achieve. In this sense, the flexibility of more informal housing options is a key factor for many inhabitants, especially in cities with high housing prices. On the other hand, unauthorized modifications reflect a spatial adaptability situation wherein the formal housing provisions do not adequately serve the residents’ needs. Residents can alter their homes to boost density, change spatial configurations, or monetize underused space without the time lag and expense of securing formal approvals. Therefore, the design of Villa Verde by Architect Aravena signifies how adaptability and flexibility should be institutionalized as an architectural model, thereby promoting the development from informality to formality through engaging people in self-help.

The qualitative analysis indicates that HI emerges via a multifaceted process, as economic drivers cannot be distilled into linear cause-and-effect processes but signify an array of financial, social–cultural regulatory, and demographic nexuses. The permutations of these drivers are unique to every place, generating an immense variety of housing informality types.

3.2.2. Complex Impacts: Dynamics Unfolded

Economic Impacts

The informal economy generated by housing informalities may significantly affect national and local economies. Informal Market Dynamics, ADU, squatting, and unauthorized modifications are all responses to the economic precarity found in the informal economy. They quickly become a parallel economy that allows for escaping moderating control instead of adhering to formal regulation, oversight, and taxation. While providing valuable housing alternatives, the shadow economy also leads to a considerable loss of tax revenue and increasing market distortions that affect the overall functioning of an economy. Informalities in housing practices continue to support the economy across various trends, even though all those earnings remain off-record. More specifically, in the case of informal housing tenure, migrants’ housing dynamics, Sub-Divided Units (SDU), and shared housing, the rental markets represent an important area where rent is collected illegally by landlords who do not declare it. This deprives governments of much-needed tax revenue that funds urban development and the provision of formal dwellings [62]. In cities like Hong Kong [41], New York [20], and London [18], notable informal subletting also occurs, with SDU deeply entrenched in high-cost urban settings. These social housing dynamics are bolstered by online settlement platforms that allow units or properties to be rented, where unregulated rental activities bypass formal housing and tax policies.

Moreover, informal funding structures play a key role in financing building or adaptation in cases of housing informality. In countries such as Nigeria [63], other options include informal lending or community-based savings groups that provide capital for conversions/extensions within formally recognized housing frameworks (the financial transactions going untaxed and flowing entirely independently of the formal banking system). Profits from these informal lending systems are unrecorded, and the interest in this money circulation remains unaccounted for, increasing the size of the untaxed informal economy even further. In Turkey [33] and Morocco [21], unauthorized modifications involve an array of informal entrepreneurs—builders, contractors, and service providers—who make a living through illegal construction activities that tweak or extend formal housing units without official permits. Such changes, often conducted without inspection or oversight, generate massive potential revenues, but are tax-free. It makes the construction market a part of the informal sector, with all profits flying under the radar in the formal economy.

The housing informality sector is a country’s most significant urban economy. However, as it does not go through formal channels, this severely handicaps the state’s capacity to earn revenue from it, ensure its safety, or develop an attractive urban development strategy for future interventions. It simultaneously underscores the continual dilemma between the demands of systemically economically excluded groups and the authoritarian mechanisms that cannot provide shelter necessities.

Social Impacts

The social impacts of housing informality are multi-layered and weaved into the residents’ experiences. Most commonly, these effects will be positive in some areas and harmful in others, depending on the type of housing trends. In Informal Market Dynamics, social impacts typically involve the development of close-knit neighborhoods in which residents pool resources together and generate informal support networks. But these communities can also suffer from social isolation, or even exclusion from the formal economy, depending on whether or not they are recognized and supported by the local governments. This juxtaposition underscores the tension between community solidarity and social exclusion. ADUs, by comparison, produce many positive social outcomes—they bring families together across generations, or create housing options for people who need them. They include a mix of residential types and create the opportunity for inter-generational living, better communities, and mixed-income neighborhoods. Squatting, on the other hand, generates more contested social consequences. Squatting communities can create strong internal ties and resistance, but often are vilified and face legal challenges. This leads to a tense social landscape in which informal inhabitants struggle to position themselves within the larger cultural weave of an urban area. As previously mentioned, in Turkey or Morocco, informal modifications are non-authorized modifications that dwellings undergo to accommodate their social and family needs. These adaptations allow residents to establish multi-generational households, take in city renters, and form informal social networks that result in joint housing and economic advantages.

Legal and Regulatory Impacts: Navigating the Grey Zones

This issue of the interaction between non-conformal modes of dwelling and legal rules is crucial for urban governance. Housing informalities are often found in a legal grey zone or at the margins of formal systems; residents either bend regulations to inhabit legally permitted structures, or evade regulation altogether to gain access to housing. This common practice raises numerous legal and regulatory dilemmas for cities, as municipal laws do not recognize these informal arrangements. Legal and regulatory effects arise from the informal recognition of rental agreements, lack of tenure security, and building codes in Informal Market Dynamics. At worst, informal rentals, shared housing, and sub-divided units operate in a legal grey zone or the black market. This results in a precarious housing scenario with no legal backup if the tenant faces disputes or evictions. This raises a critical issue for cities: How do you regulate a housing market segment that lies (partly) beyond the formal and informal systems? Urban authorities face challenges in enforcing regulations, protecting tenants, or incorporating informal markets into more extensive housing strategies due to the absence of well-defined legal frameworks for such informal practices.

Squatting, by contrast, tends to operate completely separately from official legal channels [34]. It consists of living in a property, either vacant or abandoned, without permission, whereby one is directly testing the boundaries and limitations of real estate law. Of all the legal conflicts for cities, this may be one of the most straight-ahead battles, as municipalities are focused on removing squatters while also trying to address broader social concerns around housing rights versus property rights. This includes the contested legal nature of squatter settler residences in Milan [31], along with cases such as Beijing [5], where long-drawn-out lawsuits repeatedly arise between squatter’s public estate owners and local authorities. This tension suggests the (in)capacity of (formal) legal systems to manage informalities in housing practices effectively. A primary issue from the side of cities is that informal housing elements point towards massive shortcomings in existing legal frameworks [64,65]. In addition, many regulatory mechanisms were developed when formal housing markets dominated, and have struggled to keep up with the informal nature of much housing practice. Therefore, the municipalities must respond by governing these practices using antiquated or overly rigid legal systems. Informal housing, including grey and fully extra-illegal practices, is still challenging to regulate since it concerns safety standards, urban planning policies, and the right to equal access to housing. With all these issues in perspective, cities need to develop new legal frameworks that reflect the nature of informalities in housing. Strategies that range from normalizing to regularizing and legalizing some elements of housing informality practices (like ADU or informal modifications) could be deployed as functional mechanisms for commodifying and formalizing these housing types within the rubric of more conventional urban governance. This will require establishing systemic connections between the formal and informal (subnational) systems that reshape the legal urban fabric into a more flexible and dynamic regulatory framework, leading to an environment that meets housing demands as much as possible, with minimal urban order/safety disruption.

Health and Safety Impacts: Immediate and Long-Term Concerns

In many cases of housing informality, regardless of type, one of the most common issues is related to health hazards caused by informality without compliance with formal building standards and health regiments. Factional disputes are one consequence of Informal Market Dynamics. For instance, without regulatory oversight, overcrowded living conditions can jeopardize safety. The informal rental units, sub-divided apartments, and unauthorized modifications often do not have proper ventilation, fire safety measures, or structural integrity, putting residents at risk. This is particularly true in rapidly urbanizing cities, where demand outpaces local government capacity to regulate health and safety construction procedures [66]. The health and safety impacts of ADU have been further removed, but they remain crucial. Without proper construction authorization, an unpermitted ADU can be built with insufficient plumbing or electrical infrastructure to support safe living. Hazardous indicators for squatters often emerge from living without key services such as clean water, electricity, and proper sanitation. Squatting communities usually reside in derelict or otherwise unsafe buildings, and corresponding residents occupy spaces where fires are far more likely to occur due to a slew of fire hazards. These health effects of squatting are further exacerbated by the fact that many people in these communities experience social exclusion, which prevents them from accessing essential services such as basic medical care.

Housing informality is also extensively entangled with a string of broad and different impacts—at an economic and social level, while equally at legal or health/urban development levels. The informal market dynamics are a potential threat and an opportunity for low-income groups, while ADU is an unregulated solution to low housing prices. Squatting and unauthorized modifications point to the tensions between informal residents and formal regulatory systems as residents struggle to retrofit their housing solutions within a restrictive legal system.

Ultimately, the consequences of housing informality are symptomatic of the underlying socio-economic setting that makes these practices possible. Policymakers and urban planners should implement more effective leverages by grasping the concrete issues of these impacts to enhance the resilience and adaptive capacity of informal housing communities and intervene in unsanctioned/insecure built solutions provided by deploying the necessary safety codes.

4. Discussion

Building on the synthesized results, this discussion section places the findings in the context of the existing literature. It interprets the trends and methodological insights while integrating an evaluation of the evidence’s overall strength—considering factors such as consistency, reliability, and directness—and points out areas where further research may be needed. Housing informalities (HI) are complex, multi-scalar phenomena driven by the intersecting legal, economic, social, and spatial processes found in formal or informal land markets of both the Global North and South. In this systematic literature review (SLR), we selected 27 studies on HI to perform a comprehensive analysis, which contributes to obtaining an overall empirical understanding of the global research development related to housing informality. Through this discussion, we seek to synthesize these findings and situate them in the relevant academic debates—identifying central themes, methodological lacunae, and their implications for future urban planning and development practices, policy, and future architectural and urban research. This is supported by the trend that dominated the literature: the concept of Informal Market Dynamics. Informal housing markets in the Global North and South exist as mechanisms that stand as alternatives to market imperfections, regulatory constraints, and exclusion from socio-economic opportunities [67]. Nonetheless, even if the drivers of HI are standard, their implementation is context-specific, because it depends on urban configuration forms, legal provisions, and societal norms.

Why Housing Informalities Require a Refined Selection Process

Unlike the broad concept of “informal housing,” which centers on settlements developed outside formal regulatory systems, “housing informalities” (HI) describe irregular, adaptive, or incremental practices within formally recognized frameworks of property ownership and governance. These might include unauthorized changes to legally owned homes, subdivided apartments, or semi-legal rentals in cities with functional zoning and infrastructural regulations. Studying HI demands a more precise research approach, excluding investigations into slums, shantytowns, or urban villages, where housing and land tenure exist largely outside official regulatory systems. This review highlights the often-overlooked yet growing forms of housing provision and livelihood strategies that bypass or adapt formal rules in both Global North and South contexts by concentrating on these embedded informal practices.

Beyond Conventional Boundaries

A strength of this review is that it illuminates the global scale of housing informalities, considering examples from across the globe—both in developed and developing countries. Housing violations are usually associated with the developing world, and mainly with slums or informal settlements [68,69,70]. Still, forms of this sort of informality can also be observed in rich countries, albeit under other guises [20,71], in situations such as when we see the explosion of ADU (Accessory Dwelling Units) and SDU (sub-divided units) in cities such as Los Angeles and Sydney without broad-based public consent or other significant regulatory changes that formally legitimize these housing types. Due to housing affordability challenges, informal housing practices may arise even in well-regulated, high-income nations. Rather than serving as an alternative to formal housing, housing informality should be re-envisioned as a parallel development model that adapts and evolves across diverse environments [72]. The unauthorized modifications in cities such as Rabat and Istanbul are clear examples of the ingenuity with which residents respond to failures in the formal housing supply prevailing in the Global South. In contrast, ADU and SDU developments across cities throughout the Global North suggest that many are articulating solutions that transcend hybridity, pushing standing regulatory envelopes. In examining the hybridization between traditional and modern forms in Moroccan housing, Pinson [73] shows how domestic spaces are mutated under socio-economic pressures.

Degree of Association Among the Five Major HI Trends

The analysis reveals a strong interconnection among the five key HI trends: unauthorized modifications, informal market activities, ADUs, squatting, and atypical housing. Each trend represents a distinct way of navigating or adapting to formal housing systems, yet they frequently share underlying causes such as affordability issues, regulatory gaps, and local cultural norms. For example, ADUs might start as a legally approved method to boost housing density, but eventually take on characteristics similar to unpermitted modifications—especially if homeowners expand structures without proper authorization. Likewise, unconventional housing options, such as container homes, can overlap with squatting when people occupy land or property without legal permission, highlighting the complex interplay in high-cost urban markets that drive residents toward unconventional solutions. Moreover, unregulated market dynamics—exemplified by informal financing and sub-leasing practices—can provide the hidden economic support that enables ADU construction and unauthorized alterations. Although these trends are frequently treated as isolated phenomena, they exist along a continuum of adaptive strategies addressing structural housing limitations. Appreciating these linkages offers a richer insight into how people combine multiple informal tactics to obtain shelter, thereby complicating the formulation of universal policies.

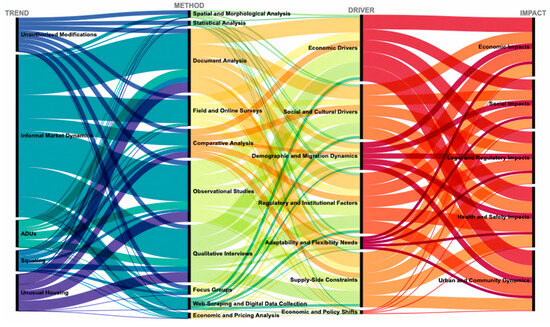

Visualizing the Interconnectedness of Trends, Methods, Drivers, and Impacts

We propose an alluvial diagram to understand better the complex relationship between trends in housing informality, the research methodologies used to study it, its underlying drivers, and its resulting impacts (Figure 5). This visualization is key to understanding the nested relationships between different dimensions of housing informalities and how they intersect across various contexts. This provides a visual aid to help examine how some trends are methodologically addressed, and what insights these methods provide concerning specific drivers and impacts. In contexts such as Turkey [33] and Morocco [21], unauthorized modifications are predominantly probed using qualitative methods, primarily via document analysis, qualitative interviews, and field/online surveys. Emphasis is often placed on these methods’ social and cultural drivers, which sheds light on how community norms, family dynamics, and economic necessity influence informal practices within legally recognized housing frameworks.

Figure 5.

Alluvial diagram of methods used for each trend.

Furthermore, the diagram reveals that although unauthorized modifications have led to significant spatial changes, spatial and morphological analysis falls short as a tool for this purpose, marking a crucial research gap. This shortcoming leaves us with an incomplete understanding of these informal practices’ architectural and urban effects, particularly their evolution over time into spatial forms. The diagram also shows that informal market dynamics and housing informality are the most widely studied trends, which correlate data and cross-research methods of economic and pricing analyses with web-scraping and digital data collection. This mix of methods also reflects the multi-faceted nature of informal markets and the underlying economic drivers, such as housing affordability crises, income inequality, market exclusion, etc. The over-representation of document analysis and field/online surveys within this trend clearly illustrates that understanding these informal markets requires a familiarity with historical/regulatory data and individuals’ day-to-day challenges. In these cases, informal housing practices—such as sub-divided units (SDU) or unregulated rental markets—are reported to both exacerbate affordability pressures and provide adaptable yet fragile housing options for economically marginalized groups.

This visualization also highlights the relatively little-discussed trends like squatting and unusual housing despite [34] their prevalence in cities like Milan, Beijing, or Oxford. Observational studies and comparative analysis have traditionally focused on these types of housing informality [11,74,75], suggesting a call for more in-depth participatory research methodologies. The social and cultural drivers associated with these trends—socio-political resistance, squatting or adaptation needs, and unusual housing forms—are typically related to broader urban dynamics, as Figure 5 illustrates. However, no economic and pricing analysis is embedded into these trends, meaning the more significant implications for housing markets and urban affordability are not clearly understood, calling for further research.

Moreover, the visualization clearly shows how trends such as squatting and unusual housing receive extremely scarce attention, notwithstanding their high presence in cities like Milan, Beijing, and Oxford. Such forms of housing informality are usually studied through observational studies and comparative analysis, indicating the value of more immersive and context-sensitive research methodologies. The social and cultural drivers of these trends, e.g., socio-political resistance in squatting or adaptability needs in unusual housing forms, are closely linked to macro-urban processes at multiple scales, which we can visualize through the diagram (see Figure 5). Nonetheless, the absence of economic and pricing analysis in these trends implies a limited understanding of their broader effects on housing markets and urban affordability, which requires more research. Additionally, the diagram sheds light on the regulatory and institutional drivers and how these components affect informality in housing practices in different places. Trends such as ADU and unauthorized modifications can all be traced back to these drivers, indicative of strict or inflexible regulatory frameworks that typically turn residents toward informal solutions. ADU emerge as an innovation in the face of the failure of a formal dominant regulatory system, providing a living space within the existing property to satisfy housing demand, especially in the high-demand housing markets of the Global North. However, as the above diagram shows, research is disproportionately concentrated on document analysis and field surveys compared to economic analysis. This reduction suppresses our grasp of how ADU fits into the broader housing market ecosystem(s) and affordability. Ultimately, the diagram shows how these informal housing practices impact urban environments across a wide spectrum, from economic impacts to urban and community dynamics. It hints at their dual function within urban environments as challenges and opportunities. Similarly, unauthorized modifications and informal market dynamics are two scenarios that may have health and safety impacts (i.e., poor living conditions or regulatory non-compliance), but also encourage urban and community dynamics, which are more responsive and adaptable to change. One of the elements of informality that is not easy to quantify is social capital, which residents within HI often rely on. The figure thus highlights that the qualitative research methods are vital to thoroughly examining the socio-cultural implications of housing informalities.

Methodological Insights and Gaps: Toward a Comprehensive Research Framework

The methodological landscape of the reviewed studies demonstrates a rapidly evolving field in which various methods are used to characterize HI. The most common categories of methods applied in our mapping are document analysis, qualitative interviews, and field/online surveys, which are directly related to the socioeconomic and regulatory complexity encompassing housing informalities. Yet, the review also highlights key methodological deficiencies obscuring our view of HI. More sophisticated analyses like spatial and morphological analysis and economic and pricing analysis are significantly lacking in research on HI trends such as unauthorized modifications and unusual housing. Spatial and morphological studies, for example, are essential to grasping how informal practices change the urban fabric, often more radically [7], where unauthorized modifications or alternative housing solutions highly transform the physicality of cities. The lack of these methods within the reviewed studies poses a potential opportunity for future research to address the spatial impact of HI, especially within high-population-density urban areas, where such an implementation can drastically affect urban planning and infrastructure [76]. This, along with the infrequent use of economic and pricing analysis, suggest that HI is not as effectively assessed by strict economic or supply/chain mechanisms. While many may understand HI as a means to cope with economic precarity [77], these practices’ more ambiguous and multifaceted relationships with other types of economies—embedded in formal housing markets, affordability, and urban inequality—remain under-theorized [78]. This would offer essential lessons in understanding the economic processes that allow informal housing markets to function—especially in cities with high demand, which are increasingly mixed up with formal housing systems [79].

Governance Gaps of Housing Informality

This study reveals a fundamental disconnect between formal governance structures—including regulatory rules, enforcement systems, and urban planning processes—and the everyday realities of households searching for shelter. In areas where institutional responses are lacking, or enforcement is inconsistent, a governance vacuum arises, leading to the rapid spread of unauthorized or unregulated modifications. The divergence between formal governance and the practical realities of housing amplifies several issues. Economically, low-income families that add unregulated extensions risk eviction or demolition. Socially and legally, communities dependent on informal financing or communal living may build closer ties, yet they remain vulnerable because their tenure is not legally secured. Health risks mount in overcrowded environments where sanitation, safety, and disease become serious concerns, while ad hoc urban expansions pressure infrastructure and alter urban morphology in unintended ways. Addressing these interlinked impacts requires policymakers and planners to align formal housing policies with residents’ practices.

The Role of Socio-Cultural Factors in Shaping Housing Informality

One thing that stands out amidst this review is the relation between migration and housing informality. Migration (internal and international) is a key driver of housing informality, especially in urban contexts where legal, financial, or social circumstances prevent migrants from accessing formal markets with a framework for understanding the impact of migration on housing dynamics among migrants [80]. Migrants worldwide are often compelled to resort to informal solutions such as AUDS and SDU [71], shared accommodations, or squatting—a reality observed in cities like Hong Kong and New York City. Such a trend underscores the need to treat migration as an essential component of housing informality, especially in light of burgeoning global mobility and urbanization. Our findings from reviewed studies indicate that informality in housing is used for survival by the migrant population. However, our results also highlight the social and cultural complexity underlying everyday practices. An example pertains to unauthorized modifications, which are frequently motivated in Turkey and Morocco by socio-cultural forces, such as multi-generational family living, which require the adaptation of physical, formal housing units. These changes erode the divide between formal and informal housing, mirroring nuanced socio-cultural practices in determining urban housing dynamics.

Government Housing Policy and Its Role in Shaping Informal Housing

Another significant aspect of our analysis is how government housing policy influences and frequently limits the dynamics of housing informalities (HI). Since these policies are usually developed for fully regulated conventional markets, they often miss the adaptive strategies that define HI. This regulatory void fails to capture the myriad forms of informal market dynamics and adaptive approaches, and it may inadvertently promote them by imposing rigid standards misaligned with residents’ actual circumstances. For example, in several cities, interventions intended to formalize informal settlements—via slum upgrading or ADU legalization—have met with mixed success. There are instances where these measures have increased housing security and safety; however, in other cases, heavy-handed enforcement has forced residents into riskier practices such as unauthorized modifications or squatting. These case studies demonstrate that while some government policies successfully incorporate informal practices into the formal sector, others restrict them and worsen housing vulnerability. Our critical review of these interventions underscores the need for a more flexible, integrative approach that aligns formal regulatory frameworks with residents’ adaptive, often informal, strategies to secure shelter.

5. Conclusions

This SLR thoroughly interrogates the complex relationships shaping housing informalities practices (HI) in the Global North and South. It uncovers the universal nature of HI and region-specific expressions of it. The review also synthesizes comprehensive knowledge of HI trends, methods, drivers, and impacts, defining complex relationships within legally recognized frameworks and urban environments. Our results show that HI is not only present within the Global South, where much of the academic research on informal settlements and slums has focused. Instead, increased levels of ADU and SDU in high-income urban centers highlight how informal housing practices are not only resilient, but adaptively respond to affordability crises, regulatory barriers, and market failures also present in the Global North. The reconceptualization not only questions the conventional dichotomy between formal and informal housing; it also calls for a more flexible theoretical framework that would allow these practices to be understood as changing over time in different urban contexts.