Smart City Innovations: The Role of Local and Global Collaborations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Local and Global Collaborations and Smart City Innovations

2.2. Collaboration for Knowledge Transfer and Innovation Adoption in Smart Cities

2.3. Collaboration for Innovation Co-Development and Experimentation in Smart Cities

2.4. Collaboration for Innovation Standardization and Scalability in Smart Cities

3. Methodology and Analysis

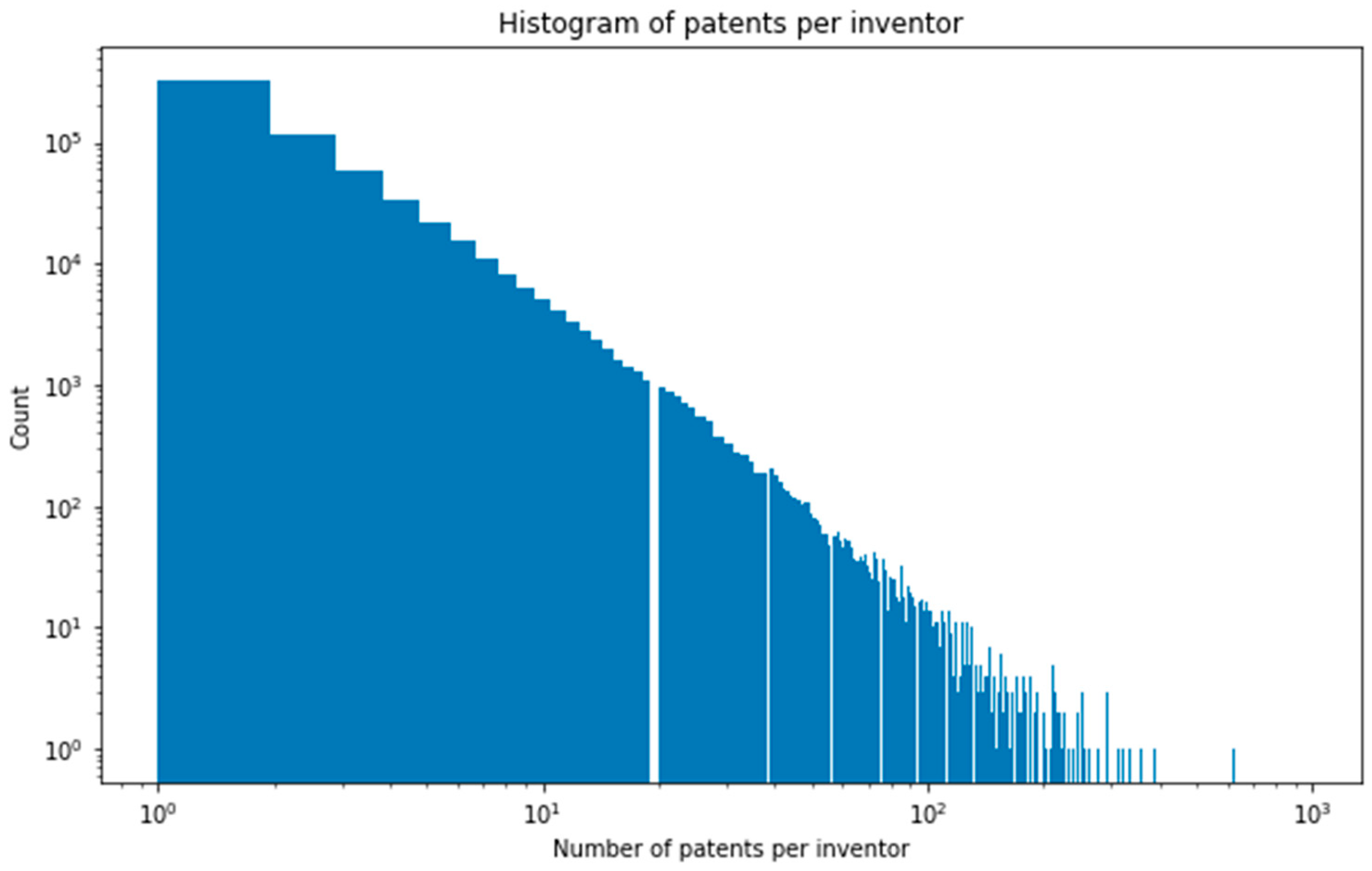

3.1. Analysis of Global Patent Data

- Frequency/enrichment screening of rank codes by their prevalence in the initial seed set of 1100 patents;

- Domain screening performed via keyword analysis to retain codes whose scope explicitly aligns with “urban infrastructure, sensing, communications, mobility, energy, and city-scale information systems”.

- Inventor unique identifier (UID);

- Inventor country;

- Patent UID;

- Patent time stamp;

- CPC code;

- Patent title;

- We sorted the dataset by patent UID and created a list of all the inventor UIDs and inventor countries associated with each patent.

- We incorporated that list into the original dataset based on patent UID to end up with a dataset in which each inventor (inventor UID) and patent (patent UID) are linked to all their co-inventors’ UIDs and countries.

- We then sorted this latter dataset by Inventor UID and created the following variables:

- ○

- Inventor UID;

- ○

- Inventor country;

- ○

- Number and list of patents authored by inventor UID;

- ○

- List of domestic linkages by inventor UID;

- ○

- List of global linkages by inventor UID;

- ○

- Inventor min date (the date of the earliest patent found for a given inventor UID);

- ○

- Inventor max date (the date of the latest patent found for a given inventor UID);

- ○

- Inventor span = inventor max date–inventor min date, in months.

3.2. Smart City Best Practices Across the Globe and the Case of Montreal

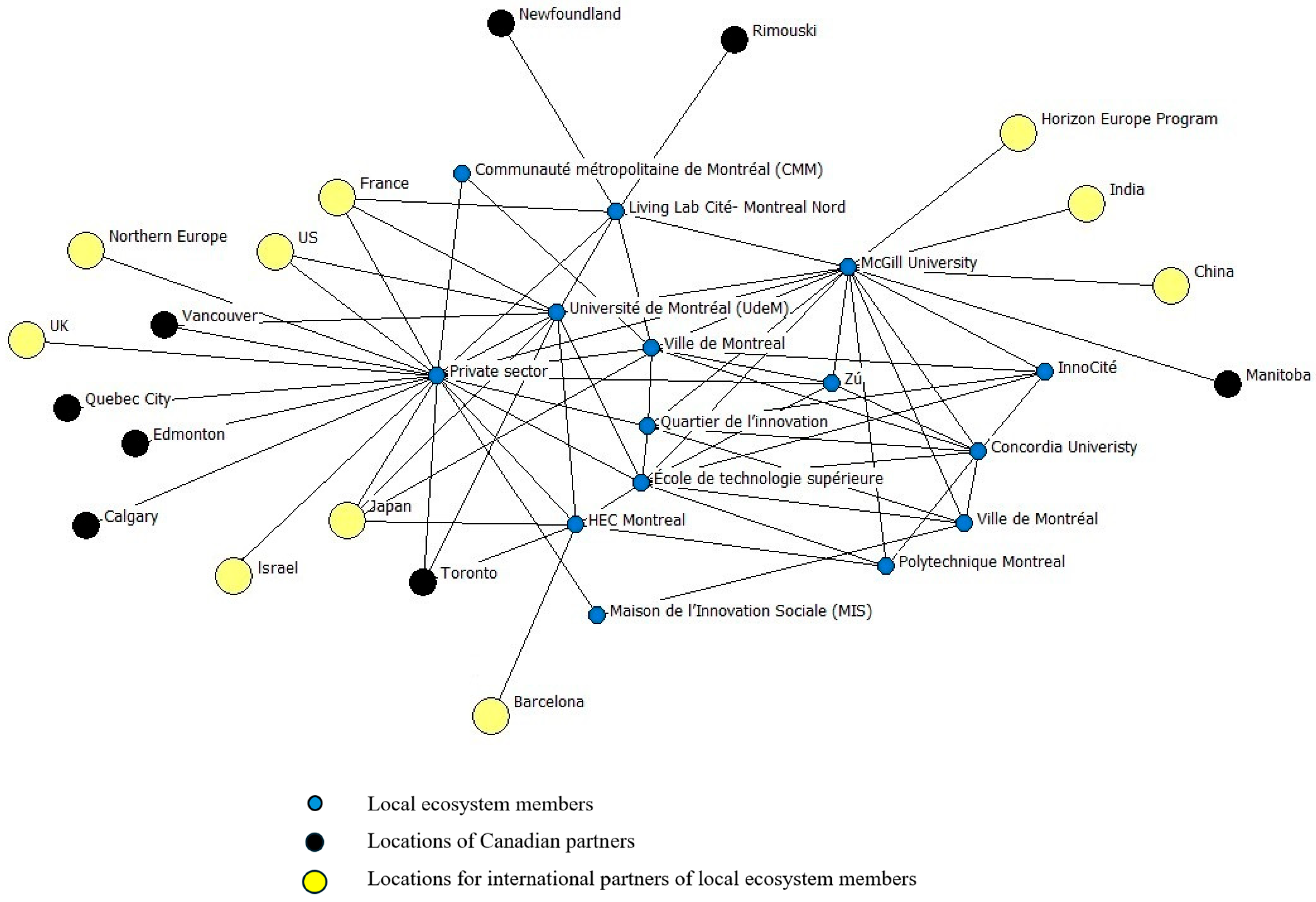

3.3. Structural Features of Montreal’s Smart City Ecosystem and Domestic Collaborations

3.4. Global Collaborations

3.5. The Impact of Local and Global Collaborations on Smart City Innovations

3.5.1. Knowledge Transfer and Innovation Adoption

3.5.2. Co-Development and Experimentation

3.5.3. Standardization and Scalability

4. Discussion

Policy Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. 256 CPC Codes Identified from Patents Selected by Abstract Analysis and Top-30 Most Relevant Smart City CPC Codes

- Top-30 most relevant smart city CPC codes

- G01C21—Navigation systems (GPS)

- 2.

- H04W52—Power management in wireless networks

- 3.

- H04W76—Wireless session management

- 4.

- Y02D30—ICT reducing energy use

- 5.

- H04W12—Security arrangements in wireless networks

- 6.

- H04L63—Network security protocols

- 7.

- H05B47—Network-controlled lighting

- 8.

- Y02B20—Energy efficiency in buildings

- 9.

- F24F11—HVAC systems control

- 10.

- F24F2120—HVAC features (e.g., sensors and controllers)

- 11.

- H02J50—Distributed energy systems

- 12.

- Y02E10—Renewable energy generation technologies

- 13.

- H02J7—Electric vehicle power supply systems

- 14.

- H04W4—Wireless interface provisioning

- 15.

- G08G1—Traffic and vehicle control systems

- 16.

- G08B6—Alarm systems and public safety

- 17.

- G08B25—Surveillance and monitoring systems

- 18.

- G06Q50—Public sector and logistics digitalization

- 19.

- G01S13—Radar-based navigation (including automotive)

- 20.

- G01S19—Satellite navigation systems (GNSS)

- 21.

- B60W30—Automated vehicle control functions

- 22.

- B60W10—Vehicle dynamic control systems

- 23.

- G06Q10—Business and asset logistics

- 24.

- G06Q20—Payment systems

- 25.

- G06Q30—Commercial interaction automation

- 26.

- G06Q40—Financial and utility transactions

- 27.

- Y02A40—Urban agriculture and water resilience

- 28.

- Y02T10—Energy-efficient transportation

- 29.

- Y02T90—Low-emission transport technology

- 30.

- G01K13—Temperature sensing systems

Appendix B. Interview Guide

- Local Collaboration:

- Could you describe the types of local collaborations (e.g., with local government, universities, startups, NGOs) you’ve engaged in (or you are aware of)? Please provide concrete examples.

- What have been the benefits and challenges of these collaborations?

- How has connectivity among local stakeholders influenced the direction of smart city innovations? Please provide concrete examples.

- Global Collaboration:

- Have you been involved in (or do you know about) any global collaborations related to smart city projects?

- What kinds of organizations or entities have you collaborated with globally (e.g., multinational tech firms, foreign municipalities, international organizations)?

- In what ways have global partnerships contributed to or shaped smart city innovation in your projects?

- Innovation outcomes?

- Project execution?

- Regulatory or governance issues?

- Local collaborative ecosystems?

- Global connectivity?

References

- Kozlowska, A.; Guarino, F.; Volpe, R.; Bisello, A.; Gabaldòn, A.; Rezaei, A.; Albert-Seifried, V.; Alpagut, B.; Vandevyvere, H.; Reda, F.; et al. Positive Energy Districts: Fundamentals, Assessment Methodologies, Modeling and Research Gaps. Energies 2024, 17, 4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attour, A.; Burger-Helmchen, T. Guest Editorial. J. Strategy Manag. 2015, 8, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myeong, S.; Shahzad, K. Integrating data-based strategies and advanced technologies with efficient air pollution management in smart cities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abutabenjeh, S.; Dimand, A.M.; Brunjes, B.M.; Azhar, A.; Nukpezah, J. Collaboration, Organizational Capacity, and Sustainability: The Cross-Sector Governance of Smart Cities. Public Adm. Q. 2024, 48, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyannemekh, B.; Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Gascó-Hernández, M. Determinants of Collaboration in the Development of Smart Cities: The Perspective of Public Libraries. EGOV-CeDEM-Epart 2022, 2022, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, J.; Manjon, M.; Crutzen, N. Factors for collaboration amongst smart city stakeholders: A local government perspective. Gov. Inf. Q. 2022, 39, 101746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Babcock, J.; Pham, T.S.; Bui, T.H.; Kang, M. Smart city as a social transition towards inclusive development through technology: A tale of four smart cities. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2023, 27 (Suppl. S1), 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rădulescu, C.M.; Slava, S.; Rădulescu, A.T.; Toader, R.; Toader, D.C.; Boca, G.D. A pattern of collaborative networking for enhancing sustainability of smart cities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathelt, H.; Malmberg, A.; Maskell, P. Clusters and knowledge: Local buzz, global pipelines and the process of knowledge creation. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2004, 28, 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joss, S.; Sengers, F.; Schraven, D.; Caprotti, F.; Dayot, Y. The smart city as global discourse: Storylines and critical junctures across 27 cities. J. Urban Technol. 2019, 26, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.L.; Wong, P.K. Reaching out and reaching within: A study of the relationship between innovation collaboration and innovation performance. Ind. Innov. 2012, 19, 539–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karger, E.; Rothweiler, A.; Brée, T.; Ahlemann, F. Building the Smart City of Tomorrow: A Bibliometric Analysis of Artificial Intelligence in Urbanization. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H. Beyond Smart: How ICT Is Enabling Sustainable Cities of the Future. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojasalo, J.; Kauppinen, H. Collaborative innovation with external actors: An empirical study on open innovation platforms in smart cities. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2016, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, C.C.; Håkonsson, D.D.; Obel, B. A smart city is a collaborative community: Lessons from smart Aarhus. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016, 59, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutten, R.; Irawati, D. Clusters, learning, and regional development: Theory and cases. In Cooperation, Clusters, and Knowledge Transfer: Universities and Firms Towards Regional Competitiveness; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Gracias, J.S.; Parnell, G.S.; Specking, E.; Pohl, E.A.; Buchanan, R. Smart cities—A structured literature review. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 1719–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, P.; Ricciardi, F.; Zardini, A. Smart cities as organizational fields: A framework for mapping sustainability-enabling configurations. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhechba, M.; Bouzouane, A.; Gaboury, S.; Gouin-Vallerand, C.; Giroux, S.; Bouchard, B. A novel Bluetooth low energy based system for spatial exploration in smart cities. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 77, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, A. Unlocking the future: Fostering human–machine collaboration and driving intelligent automation through industry 5.0 in smart cities. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 2742–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, B., Jr. Exploring data driven initiatives for smart city development: Empirical evidence from techno-stakeholders’ perspective. Urban Res. Pract. 2022, 15, 529–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashef, M.; Visvizi, A.; Troisi, O. Smart city as a smart service system: Human-computer interaction and smart city surveillance systems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 124, 106923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Real, C.; Ward, C.; Sartipi, M. What do people want in a smart city? Exploring the stakeholders’ opinions, priorities and perceived barriers in a medium-sized city in the United States. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2023, 27 (Suppl. S1), 50–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohendet, P.; Grandadam, D.; Simon, L.; Capdevila, I. Epistemic communities, localization and the dynamics of knowledge creation. J. Econ. Geogr. 2014, 14, 929–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohendet, P.; Grandadam, D.; Simon, L. The anatomy of the creative city. Ind. Innov. 2010, 17, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, T.T.; Vien, T.D.; Tuan, N.T. Building Smart Urban Areas: Case Study in Pleiku City, Vietnam. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleya, C.; Purnomo, A.; Madyatmadja, E.D.; Karmagatri, M. Smart city applications: A patent landscape exploration. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 227, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Babb, C.; Tye, M.; Hussein, F. The Wharf Street Smart Park Story: A Guide to Navigating Multi-Stakeholder Innovation in Smart Cities. Sustainability 2024, 16, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eremia, M.; Toma, L.; Sanduleac, M. The smart city concept in the 21st century. Procedia Eng. 2017, 181, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repette, P.; Sabatini-Marques, J.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Sell, D.; Costa, E. The evolution of city-as-a-platform: Smart urban development governance with collective knowledge-based platform urbanism. Land 2021, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akterujjaman, S.M.; Mulder, R.; Kievit, H. The influence of strategic orientation on co-creation in smart city projects: Enjoy the benefits of collaboration. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 1597–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyannemekh, B.; Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Gascó-Hernández, M. Exploring emergent collaborations for digital transformation in local governments: The engagement of public libraries in the development of smart cities. Public Policy Adm. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartelt, V.L.; Urbaczewski, A.; Mueller, A.G.; Sarker, S. Enabling collaboration and innovation in Denver’s smart city through a living lab: A social capital perspective. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Cockburn, I.; Galasso, A.; Oettl, A. Why are some regions more innovative than others? The role of small firms in the presence of large labs. J. Urban Econ. 2014, 81, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glückler, J. Knowledge, networks and space: Connectivity and the problem of non-interactive learning. Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 880–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y. Toward sustainable governance: Strategic analysis of the smart city Seoul portal in Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myeong, S.; Bokhari, S.A.A. Building participative E-Governance in smart cities: Moderating role of institutional and technological innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audouin, M.; Finger, M. The development of Mobility-as-a-Service in the Helsinki metropolitan area: A multi-level governance analysis. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2018, 27, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenović, M.N.; Haavisto, N. Interpretative flexibility and conflicts in the emergence of Mobility as a Service: Finnish public sector actor perspectives. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2021, 9, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammers-Goodwin, S.I. Bridging the Gaps Between Humans and Their Infrastructure: What Are the Challenges for Citizen Engagement Introduced by Increasing Smart Urban Infrastructure and How Might Those Challenges be Mitigated? Ph.D. Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; de Villafranca, A.E.M.; Sipetas, C. Sensing multi-modal mobility patterns: A case study of helsinki using bluetooth beacons and a mobile application. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Osaka, Japan, 17–20 December 2022; pp. 2007–2016. [Google Scholar]

- Israilidis, J.; Odusanya, K.; Mazhar, M.U. Exploring Knowledge Management Perspectives in Smart City Research: A Review and Future Research Agenda. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 56, 101989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, D.E.; Izadgoshasb, I.; Pudney, S.G. Smart city collaboration: A review and an agenda for establishing sustainable collaboration. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, R.; Sengers, F.; Spaeth, P.; Xie, L.; Cheshmehzangi, A.; De Jong, M. Urban experimentation and institutional arrangements. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasi, S.; Ganzaroli, A.; De Noni, I. Smartening sustainable development in cities: Strengthening the theoretical linkage between smart cities and SDGs. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 80, 103793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaide Muñoz, L.; Rodríguez Bolívar, M.P. Different levels of smart and sustainable cities construction using e-participation tools in European and Central Asian countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, D.E.; Pudney, S.; Gomes, R.C.; Sarturi, G. Smart City Capacities: Extant Knowledge and Future Research for Sustainable Practical Applications. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Patents | Domestic Linkages | Global Linkages | Inventor Span | Inventor Last Year of Patent Publication | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patents | |||||

| Domestic linkages | 0.2685 | ||||

| Global linkages | 0.5631 | 0.2351 | |||

| Inventor span | 0.4028 | 0.1964 | 0.4148 | ||

| Inventor’s last year of patent publication | 0.1379 | 0.2029 | 0.1370 | 0.1808 | |

| Mean | 3.302262 | 4.806028 | 1.225867 | 31.91591 | 2015.363 |

| S.D. | 8.080304 | 6.452837 | 0.5916368 | 58.43059 | 9.022488 |

| Variables | Dependent Variable: Number of Patents Coefficients and Standard Errors |

|---|---|

| Domestic linkages | 0.047 *** (0.0002) |

| Global linkages | 0.152 *** (0.001) |

| Inventor span | 0.008 *** (0.00002) |

| Inventor’s last year of patent publication | 0.015 *** (0.0001) |

| Number of observations | 640,624 |

| LR chi2(4) | 600,279.13 |

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 |

| Log likelihood | −1,191,277.9 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.2012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Turkina, E.; Sultana, N.; Oreshkin, B. Smart City Innovations: The Role of Local and Global Collaborations. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120505

Turkina E, Sultana N, Oreshkin B. Smart City Innovations: The Role of Local and Global Collaborations. Urban Science. 2025; 9(12):505. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120505

Chicago/Turabian StyleTurkina, Ekaterina, Nasrin Sultana, and Boris Oreshkin. 2025. "Smart City Innovations: The Role of Local and Global Collaborations" Urban Science 9, no. 12: 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120505

APA StyleTurkina, E., Sultana, N., & Oreshkin, B. (2025). Smart City Innovations: The Role of Local and Global Collaborations. Urban Science, 9(12), 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120505