Parametric Optimization of Urban Street Tree Placement: Computational Workflow for Dynamic Shade Provision in Hot Climates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Why Traditional Urban Design Fails to Address Extreme Heat

3. The Emergence of Climate-Responsive Urban Design

4. Integrating Artificial Intelligence and Computational Design in Climate Adaptation

5. Methodology

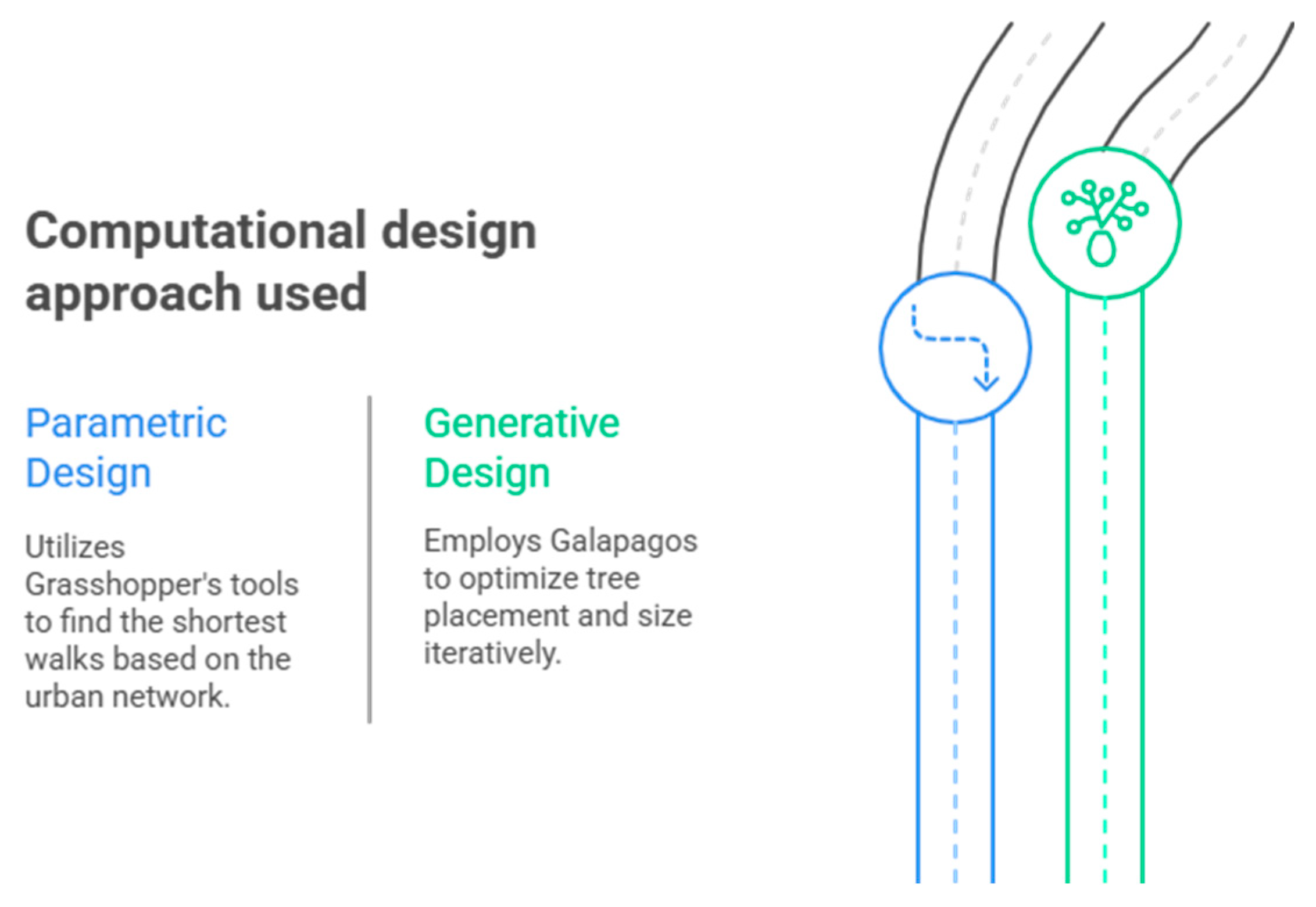

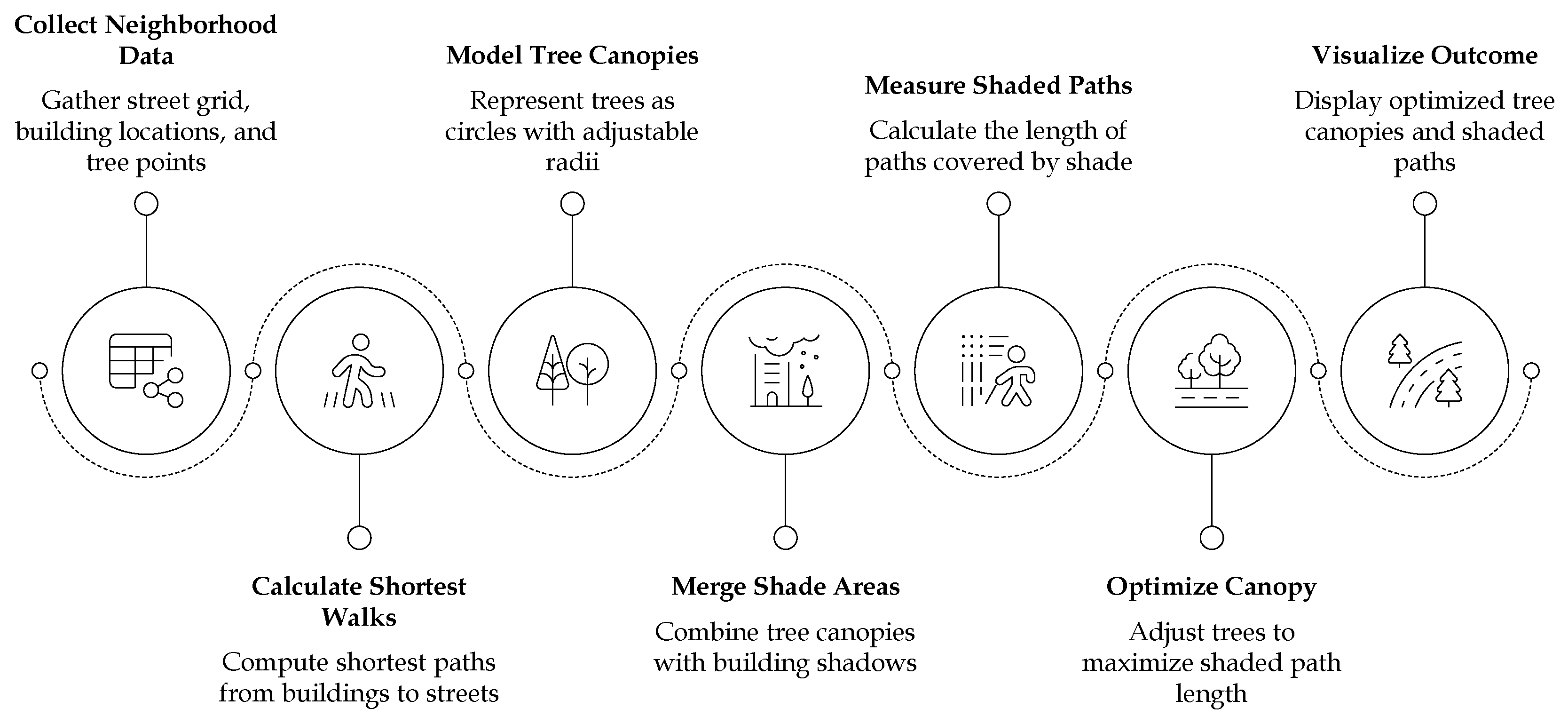

5.1. Overview of the Computational Workflow Framework, (Figure 1)

- -

- Shade score (proportion of target shaded area)

- -

- Overlap penalty (canopy overlapping with building or forbidden zones)

- -

- Spacing (distance) penalty (penalise inter-tree distances below minimum)

- -

- Structural violations (hard constraint count normalized)

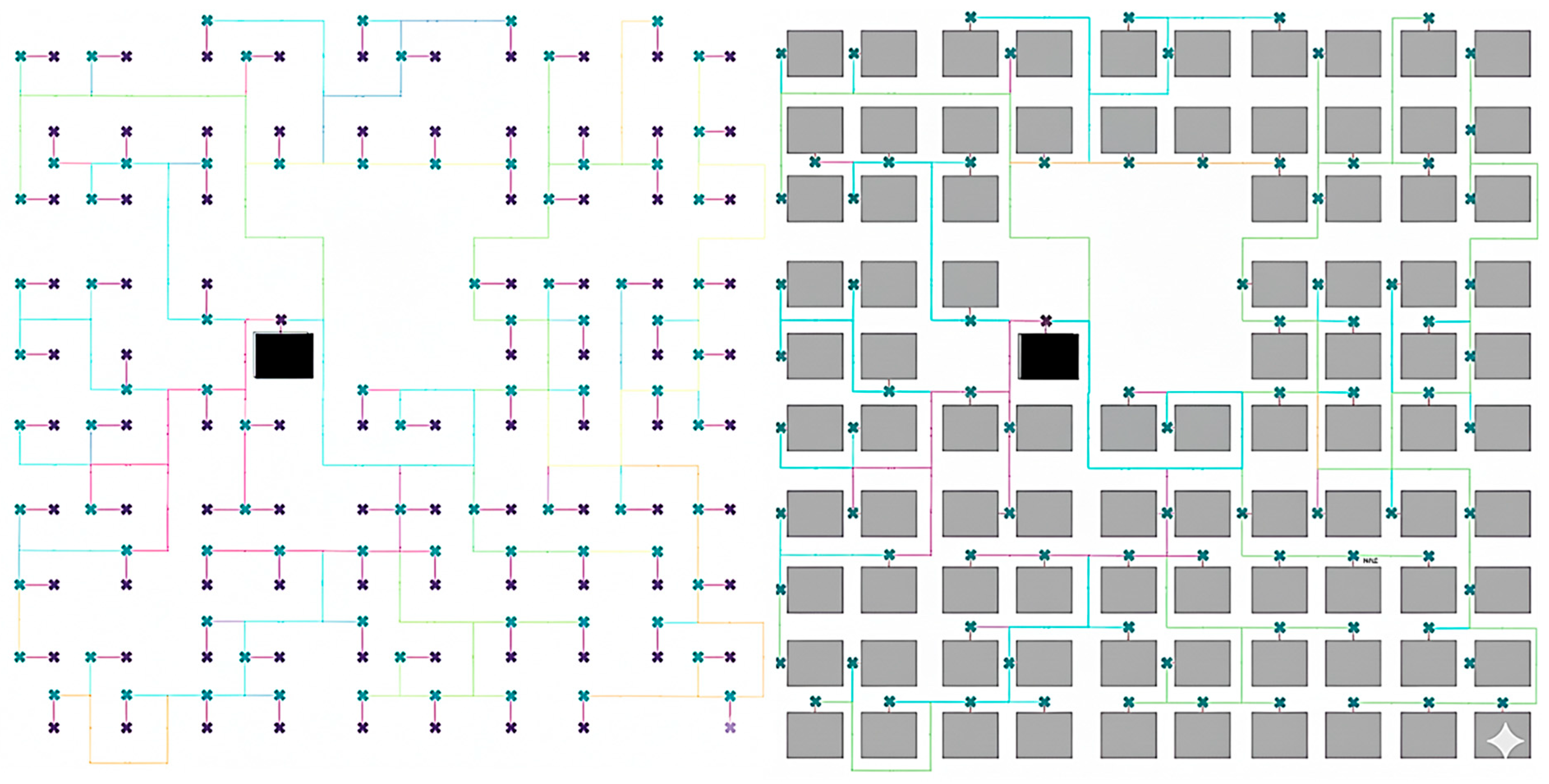

- Phase 1: Parametric Path Network Analysis

- 2.

- Phase 2: Generative Optimization of Tree Placement

- 1.

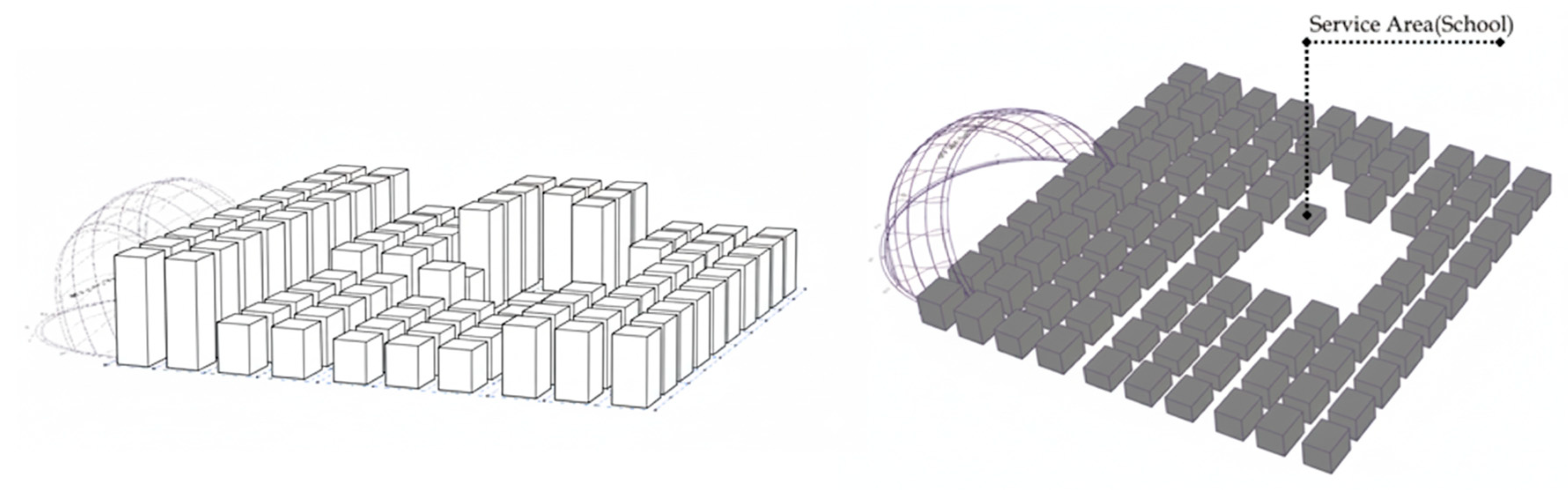

- Phase 1: Parametric Courtyard Geometry and Exposure Mapping

- 2.

- Phase 2: Generative Multi-Constraint Configuration

5.2. Model Validation

6. Results

6.1. Case Study 1

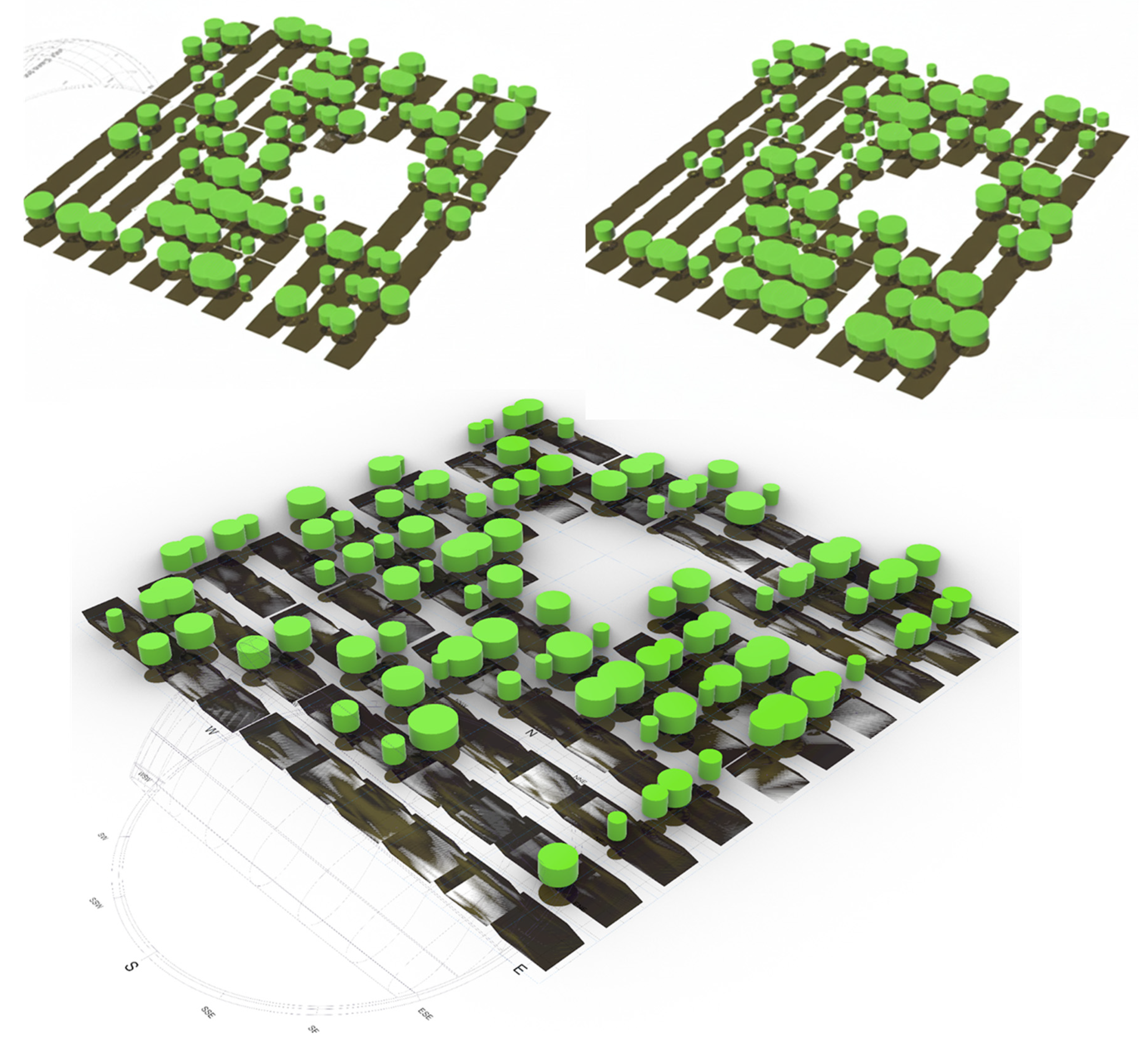

6.2. Case Study 2

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tamminga, K.; Cortesão, J.; Bakx, M. Convivial Greenstreets: A Concept for Climate-Responsive Urban Design. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Lin, Y.; Li, Q. The impact of urbanization on China’s residential energy consumption. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2019, 49, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Gao, Y.; Fang, C.; Yang, Z. Global urban greening and its implication for urban heat mitigation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2417179122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdinezhad, J.; Sedghpour, B.S.; Nabi, R.N. An Evaluation of the Influence of Environmental, Social and Cultural factors on the Socialization of Traditional Urban Spaces (Case Study: Iranian Markets). Environ. Urban. ASIA 2020, 11, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, A.; Fung, A.; Li, S. GIS Modeling of Solar Neighborhood Potential at a Fine Spatiotemporal Resolution. Buildings 2014, 4, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Sánchez, C.; Giannelli, D.; Agugiaro, G.; Stoter, J. Comparative Analysis of Geospatial Tools for Solar Simulation. Trans. GIS 2025, 29, e13296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troost, C.; Walter, T.; Berger, T. Climate, energy and environmental policies in agriculture: Simulating likely farmer responses in Southwest Germany. Land Use Policy 2015, 46, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, S.; Aigbavboa, C.; Oke, A. Revolutionising Green Construction: Harnessing Zeolite and AI-Driven Initiatives for Net-Zero and Climate-Adaptive Buildings. Buildings 2025, 15, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandsma, S.; Lenzholzer, S.; Carsjens, G.J.; Brown, R.D.; Tavares, S. Implementation of urban climate-responsive design strategies: An international overview. J. Urban Des. 2024, 29, 598–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratti, C.; Raydan, D.; Steemers, K. Building form and environmental performance: Archetypes, analysis and an arid climate. Energy Build 2003, 35, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozd, P.; Kapica, J.; Jurasz, J.; Dąbek, P. Evaluating cities’ solar potential using geographic information systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 209, 115112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, Q.; Ji, L.; Xie, Y.; Qiao, Q.; Huang, G.; Xiao, K. A GIS-based multi-criteria decision making method for the potential assessment and suitable sites selection of PV and CSP plants. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaloo, K.; Ali, T.; Chiu, Y.R.; Sharifi, A. Optimal site selection for the solar-wind hybrid renewable energy systems in Bangladesh using an integrated GIS-based BWM-fuzzy logic method. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 283, 116899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, N.; Wei, L.; Zhang, Z. Optimal site selection study of wind-photovoltaic-shared energy storage power stations based on GIS and multi-criteria decision making: A two-stage framework. Renew Energy 2022, 201, 1139–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Li, D.; Liu, Z.; Brown, R.D. Approaches for identifying heat-vulnerable populations and locations: A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 799, 149417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab, R.A.; Fekry, A.A.; Hamed, R.E.-D. The effective landscape design parameters with high reflective hardscapes: Guidelines for optimizing human thermal comfort in outdoor spaces by design -a case on hot arid climate weather. Comput. Urban Sci. 2025, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Resilient Urban Design Concept in the Context of Climate Change. Adv. Econ. Manag. Political Sci. 2024, 123, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhananga, A.K.; Davenport, M.A. Community attachment, beliefs and residents’ civic engagement in stormwater management. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 168, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deilami, K.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Liu, Y. Urban heat island effect: A systematic review of spatio-temporal factors, data, methods, and mitigation measures. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2018, 67, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derix, C. Digital masterplanning: Computing urban design. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Urban Des. Plan. 2012, 165, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S. Harnessing Big Data and Machine Learning for Climate Change Predictions and Mitigation. In Maintaining a Sustainable World in the Nexus of Environmental Science and AI.; IGI Global: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 383–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, F.; Glover, R.; Klingman, D. Computational study of an improved shortest path algorithm. Networks 1984, 14, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veghel, J.; Dane, G.; Agugiaro, G.; Borgers, A. Human-centric computational urban design: Optimizing high-density urban areas to enhance human subjective well-being. Comput. Urban Sci. 2024, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanzl, M.; Tofiluk, A.; Zinowiec-Cieplik, K.; Grochulska-Salak, M.; Nowak, A. The Role of Vegetation in Climate Adaptability: Case Studies of Lodz and Warsaw. Urban Plan 2021, 6, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N. Greening the mainstream: Party politics and the environment. Environ. Politics 2013, 22, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, F. How are green spaces associated with chronic disease incidence in Australia? Direct health benefits and interactive effects with socioeconomic status based on multiple green space indicators. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 121, 106229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzholzer, S.; Carsjens, G.J.; Brown, R.D.; Tavares, S.; Vanos, J.K.; Kim, Y.; Lee, K. Awareness of urban climate adaptation strategies—An international overview. Urban Climb 2020, 34, 100705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, M.; Ibrahim, Y.; Hanafi, E.; Barakat, M. Would LEED-UHI greenery and high albedo strategies mitigate climate change at neighborhood scale in Cairo, Egypt? Build. Simul. 2018, 11, 1273–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthi, M.A.; Lenzholzer, S.; Cortesão, J. Climate responsive design in urban open spaces in hot arid climates: A systematic literature review. Discov. Cities 2025, 2, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Dallal, N.; Visser, F. A climate responsive urban design tool: A platform to improve energy efficiency in a dry hot climate. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2017, 36, 738–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Chen, L. High-Rise Urban Form and Microclimate; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.H.H.; Cai, M.; Ren, C.; Huang, Y.; Liao, C.; Yin, S. Modelling building energy use at urban scale: A review on their account for the urban environment. Build. Environ. 2021, 205, 108235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gatto, E.; Gao, Z.; Buccolieri, R.; Morakinyo, T.E.; Lan, H. The “plant evaluation model” for the assessment of the impact of vegetation on outdoor microclimate in the urban environment. Build. Environ. 2019, 159, 106151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, M.Z.; Chehab, A.I. Materials and design concepts for space-resilient structures. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2018, 98, 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, B.A.; Coutts, A.M.; Livesley, S.J.; Harris, R.J.; Hunter, A.M.; Williams, N.S.G. Planning for cooler cities: A framework to prioritise green infrastructure to mitigate high temperatures in urban landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 134, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmejeed, A.Y.; Gruehn, D. Optimizing an efficient urban tree strategy to improve microclimate conditions while considering water scarcity: A case study of Cairo. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, H.; Fahmy, M.; Gira, A. Climate Based Design Decision Support for Urban Village Development: A case study in Nuba, Egypt. Int. Conf. Civ. Archit. Eng. 2012, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zacharias, J. Landscape modification for ambient environmental improvement in central business districts—A case from Beijing. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukkavaara, J.; Shadram, F. An integrated optimization and sensitivity analysis approach to support the life cycle energy trade-off in building design. EnergyBuild 2021, 253, 111529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cugurullo, F.; Caprotti, F.; Cook, M.; Karvonen, A.; MᶜGuirk, P.; Marvin, S. The rise of AI urbanism in post-smart cities: A critical commentary on urban artificial intelligence. Urban Stud. 2024, 61, 1168–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvin, S.; While, A.; Chen, B.; Kovacic, M. Urban AI in China: Social control or hyper-capitalist development in the post-smart city? Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 1030318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubchikov, O.; Thornbush, M. Artificial Intelligence and Robotics in Smart City Strategies and Planned Smart Development. Smart Cities 2020, 3, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Y.; Gutman, G. Aging, artificial intelligence, and the built environment in smart cities: Ethical considerations. Gerontechnology 2023, 22, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luusua, A.; Ylipulli, J.; Foth, M.; Aurigi, A. Urban AI: Understanding the emerging role of artificial intelligence in smart cities. AI Soc 2023, 38, 1039–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, S.; Farooq, B.; Basheer, S.; Walia, S. Balancing Environmental Sustainability and Privacy Ethical Dilemmas in AI-Enabled Smart Cities; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, C.; Page, J.; Kwak, Y.; Deal, B.; Kalantari, Z. AI Analytics for Carbon-Neutral City Planning: A Systematic Review of Applications. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qin, S.; Li, J.; Jin, T. Artificial Intelligence and Street Space Optimization in Green Cities: New Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, T.; Yang, Y.; Samaranayake, S.; Saraf, N. Urbano: A Tool to Promote Active Mobility Modeling and Amenity Analysis in Urban Design. Technol.|Archit. + Des. 2020, 4, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veisi, O.; Shakibamanesh, A.; Rahbar, M. Using intelligent multi-objective optimization and artificial neural networking to achieve maximum solar radiation with minimum volume in the archetype urban block. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 86, 104101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camporeale, P.E.; Mercader-Moyano, P. Towards nearly Zero Energy Buildings: Shape optimization of typical housing typologies in Ibero-American temperate climate cities from a holistic perspective. Sol. Energy 2019, 193, 738–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Xu, N.; Liu, K.; Yu, G. Urban layout optimization based on genetic algorithm for microclimate performance in the cold region of China. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortmann, T.; Cichocka, J.; Waibel, C. Simulation-based optimization in architecture and building engineering—Results from an international user survey in practice and research. EnergyBuild 2022, 259, 111863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badii, C.; Bellini, P.; Cenni, D.; Chiordi, S.; Mitolo, N.; Nesi, P.; Paolucci, M. Computing 15MinCityIndexes on the Basis of Open Data and Services. In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2021, Cagliari, Italy, 13–16 September 2021; pp. 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaofang, S.; Ying, X.; Ning, G.; Jingru, Y. A Computation Model for Proximity. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Image Processing and Computer Applications (ICIPCA), Shenyang, China, 28–30 June 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretzsch, H.; Biber, P.; Uhl, E.; Dahlhausen, J.; Rötzer, T.; Caldentey, J.; Koike, T.; van Con, T.; Chavanne, A.; Seifert, T.; et al. Crown size and growing space requirement of common tree species in urban centres, parks, and forests. Urban Urban Green 2015, 14, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, D.; Seifert, S.; Pretzsch, H. Structural crown properties of Norway spruce (Picea abies [L.] Karst.) and European beech (Fagus sylvatica [L.]) in mixed versus pure stands revealed by terrestrial laser scanning. Trees—Struct. Funct. 2013, 27, 1035–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldens, W.; Taubenböck, H.; Esch, T.; Heiden, U.; Wurm, M. Analysis of surface thermal patterns in relation to urban structure types: A case study for the city of Munich. Remote Sens. Digit. Image Process. 2013, 17, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enquist, B.J.; West, G.B.; Brown, J.H. Extensions and evaluations of a general quantitative theory of forest structure and dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 7046–7051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishii, H.T.; Tanabe, S.I.; Hiura, T. Exploring the relationships among canopy structure, stand productivity, and biodiversity of temperate forest ecosystems. For. Sci. 2004, 50, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, C.Y. Resolving intractable soil constraints in urban forestry through research–practice synergy. Socioecon. Pract. Res. 2019, 1, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.; Maing, M.; Ng, E. Observational studies of mean radiant temperature across different outdoor spaces under shaded conditions in densely built environment. Build. Environ. 2017, 114, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmejeed, A.Y.; Gruehn, D. Optimization of Microclimate Conditions Considering Urban Morphology and Trees Using ENVI-Met: A Case Study of Cairo City. Land 2023, 12, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meliouh, F.; Ghanemi, F.; Hamel, K.; Nasri, M.; Makhloufi, S. Greening the arid: The impact of urban vegetation on the outdoor thermal comfort in hot and dry city. South Fla. J. Dev. 2024, 5, e4718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Li, S.; Xing, X.; Zhou, X.; Kang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Li, Y. Cooling Benefits of Urban Tree Canopy: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naboni, E.; Natanian, J.; Brizzi, G.; Florio, P.; Chokhachian, A.; Galanos, T.; Rastogi, P. A digital workflow to quantify regenerative urban design in the context of a changing climate. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 113, 109255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirste, K.K.; Monge, P.R. Computing dynamic organizational proximity: The PROXTIME computer program. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. 1983, 15, 89–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F.T.; Costa, F. The Quest for Proximity: A Systematic Review of Computational Approaches towards 15-Minute Cities. Architecture 2023, 3, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

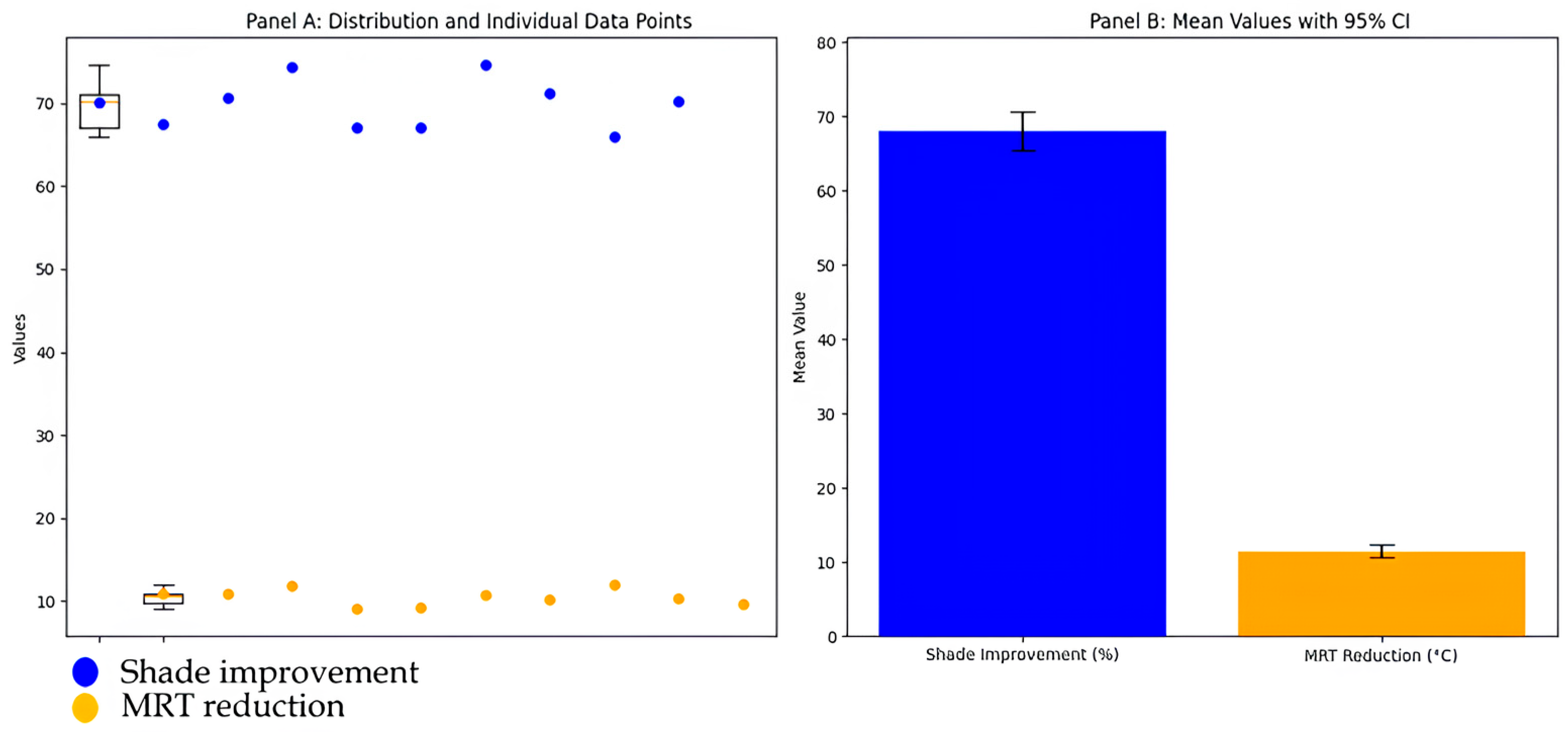

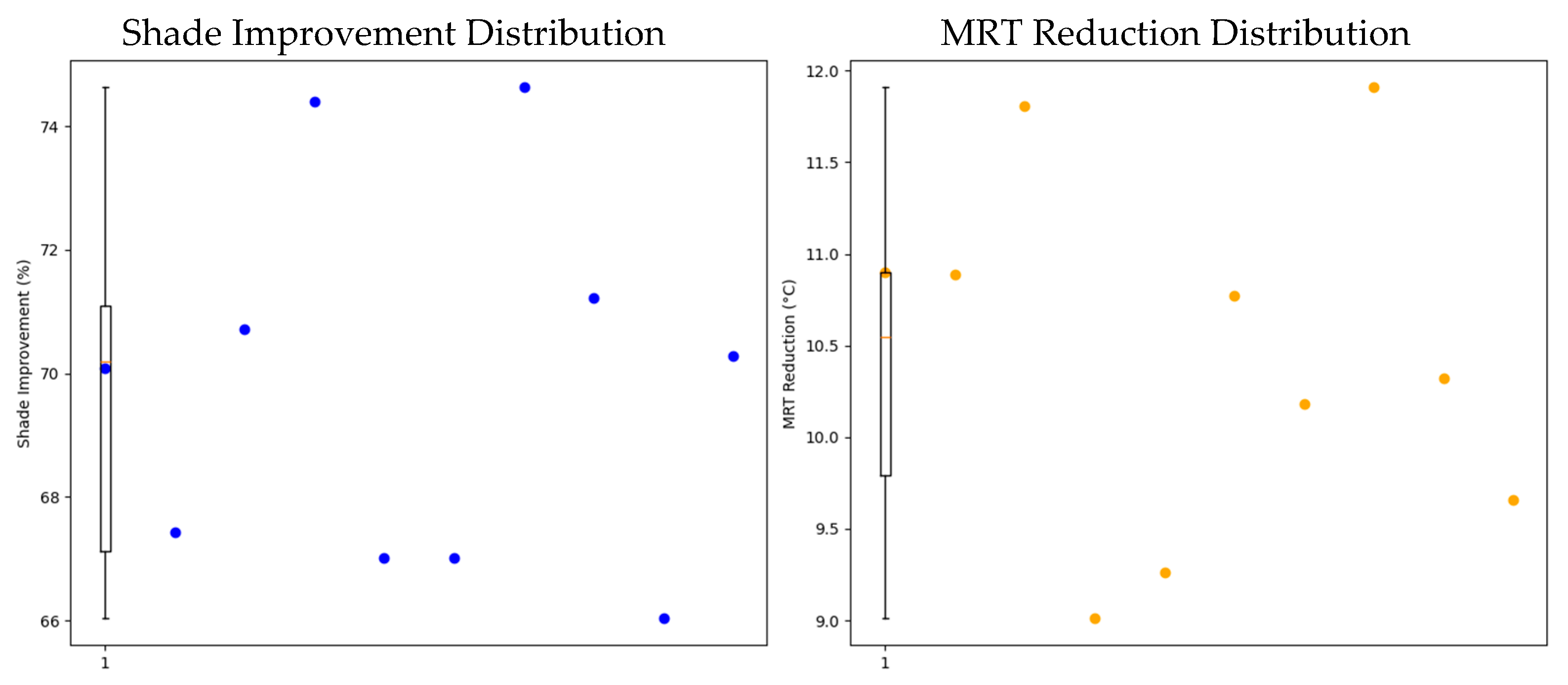

| Run | Shade Improvement (%) | MRT Reduction (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70.09 | 10.90 |

| 2 | 67.42 | 10.89 |

| 3 | 70.72 | 11.81 |

| 4 | 74.40 | 9.01 |

| 5 | 67.02 | 9.26 |

| 6 | 67.02 | 10.77 |

| 7 | 74.63 | 10.18 |

| 8 | 71.22 | 11.91 |

| 9 | 66.03 | 10.32 |

| 10 | 70.28 | 9.66 |

| Metric | Mean | SD | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) | p-Value | Effect Size (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shade Improvement (%) | 68.0 | 4.2 | 65.4 | 70.6 | 0.001 | 1.45 |

| MRT Reduction (°C) | 11.5 | 1.3 | 10.7 | 12.3 | 0.002 | 1.72 |

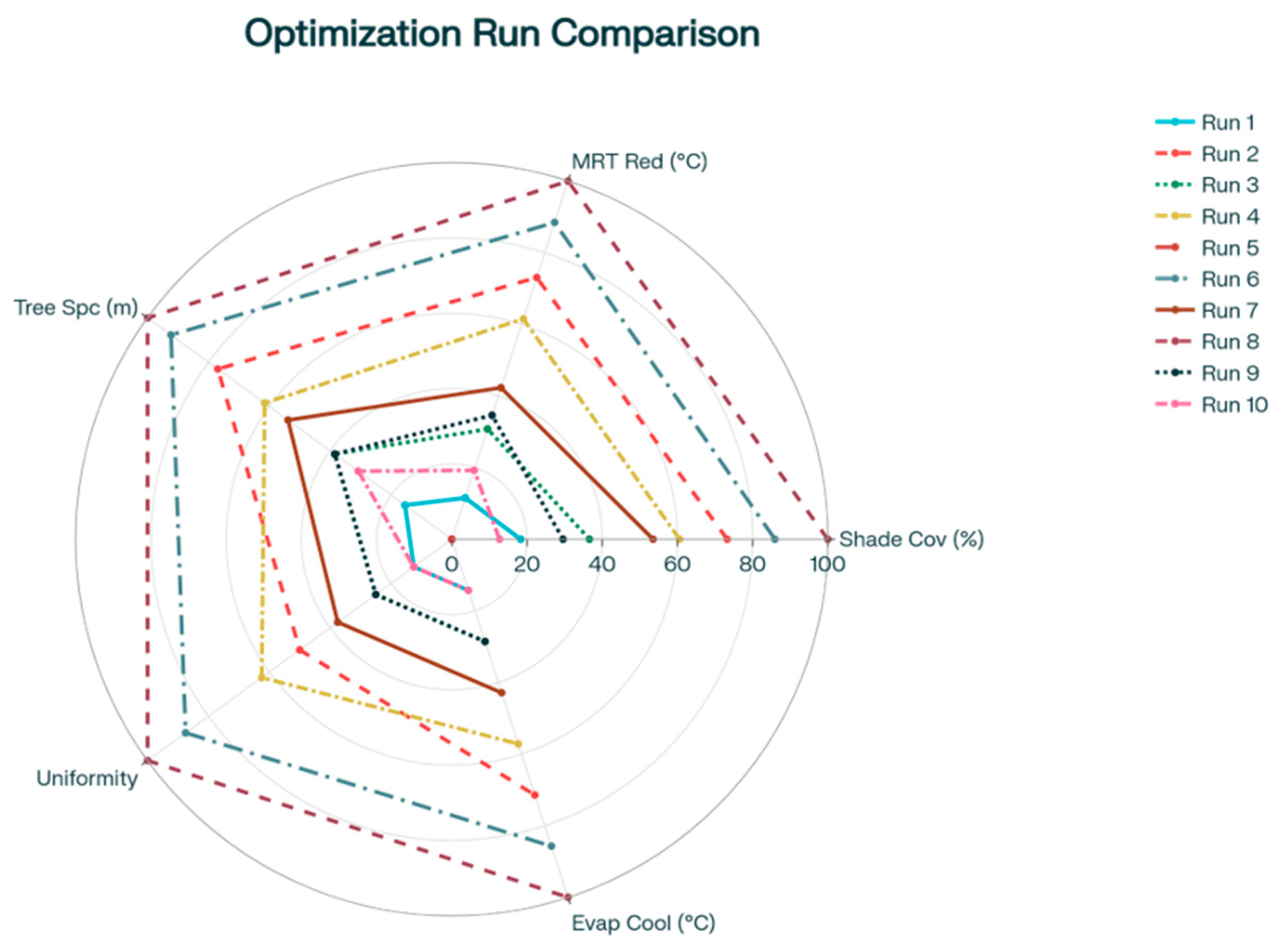

| Run | Tree Count | Shade Coverage (%) | MRT Reduction (°C) | Inter-Tree Spacing (m) | Shade Uniformity Index | Evaporative Cooling (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 | 50.2 | 8.5 | 4.7 | 0.85 | 2.3 |

| 2 | 12 | 54.1 | 10.1 | 5.5 | 0.88 | 2.7 |

| 3 | 11 | 51.5 | 9.0 | 5.0 | 0.86 | 2.4 |

| 4 | 10 | 53.2 | 9.8 | 5.3 | 0.89 | 2.6 |

| 5 | 8 | 48.9 | 8.2 | 4.5 | 0.84 | 2.2 |

| 6 | 13 | 55.0 | 10.5 | 5.7 | 0.91 | 2.8 |

| 7 | 12 | 52.7 | 9.3 | 5.2 | 0.87 | 2.5 |

| 8 | 14 | 56.0 | 10.8 | 5.8 | 0.92 | 2.9 |

| 9 | 10 | 51.0 | 9.1 | 5.0 | 0.86 | 2.4 |

| 10 | 9 | 49.8 | 8.7 | 4.9 | 0.85 | 2.3 |

| Metric | Mean ± SD | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Shade Coverage (%) | 52.2 ± 3.1 | [50.0, 54.4] |

| MRT Reduction (°C) | 9.2 ± 1.1 | [8.4, 10.0] |

| Inter-tree Spacing (m) | 5.1 ± 0.6 | [4.5, 5.7] |

| Shade Uniformity Index | 0.87 ± 0.04 | [0.83, 0.91] |

| Evaporative Cooling (°C) | 2.5 ± 0.2 | [2.3, 2.7] |

| Guideline | Threshold/Rule | Implementation Step | Rationale (from Simulations) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Minimum Shade Target | ≥70% shade coverage at 14:00 (paths); ≥50% (courtyards) | Use Ladybug Tools to verify pre-design targets; for a 200 m path, this typically requires ~18–22 trees | MRT fell below 40 °C only when shading exceeded ~65%; Case 1 achieved 68%, Case 2 achieved 52% |

| 2. Inter-Tree Spacing | 6.5–8.0 m (streets); 4.0–5.5 m (courtyards) | Enforce spacing rules in Grasshopper; flag violations automatically | Case 1 spacing stabilized at 7.2 m ± 0.8 m; Case 2 at 5.1 m ± 0.6 m, preventing root conflict and canopy overlap |

| 3. Canopy Radius Selection | 4–6 m | Match species to canopy radius: Acacia saligna, Ficus microcarpa → 4–5 m; Tipuana tipu → 5–6 m | Radius range aligns with 95% CI of optimized solutions and ensures pedestrian clearance (≥2.4 m) |

| 4. Phased Intervention Priority | Phase 1: MRT > 50 °C; Phase 2: 45–50 °C; Phase 3: <45 °C | Export MRT heat maps, segment paths, assign tree budgets according to thermal severity | Post-optimization maps show residual red edges (>50 °C), indicating critical segments for early intervention |

| 5. Shade Equity Check | Shade Uniformity Index ≥ 0.85 | Compute SD of shade % across 10 m grid cells; re-optimize if <0.85 | Case 2 achieved 0.87 ± 0.04, ensuring no localized hotspots |

| 6. Maintenance Buffer | Allow ±15% canopy-growth buffer | Scale canopy radii by ×1.15 in CAD during final layout | Reflects typical mature spread over 10–15 years (arboricultural data) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elkhateeb, S.; Anwar, R. Parametric Optimization of Urban Street Tree Placement: Computational Workflow for Dynamic Shade Provision in Hot Climates. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120504

Elkhateeb S, Anwar R. Parametric Optimization of Urban Street Tree Placement: Computational Workflow for Dynamic Shade Provision in Hot Climates. Urban Science. 2025; 9(12):504. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120504

Chicago/Turabian StyleElkhateeb, Samah, and Raneem Anwar. 2025. "Parametric Optimization of Urban Street Tree Placement: Computational Workflow for Dynamic Shade Provision in Hot Climates" Urban Science 9, no. 12: 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120504

APA StyleElkhateeb, S., & Anwar, R. (2025). Parametric Optimization of Urban Street Tree Placement: Computational Workflow for Dynamic Shade Provision in Hot Climates. Urban Science, 9(12), 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120504