Translating Urban Resilience into Deployable Streetscapes: A Sense-of-Place–Mediated Measurement–Choice Framework with Threshold Identification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Urban Resilience: From Slogan to Street Scale Translation

2.2. Spirit of Place and Its Mediating Role

2.3. Architectural–Landscape Modalities Tied to Resilience

2.4. Measuring Preferences and Trade-Offs at the Human Scale

2.5. What Existing Evidence Supports—And What It Does Not

3. Experimental Design

3.1. Research Logic and Evidence Base

3.2. Structured Design of Phase 1 Questionnaires: Mapping Constructs to Items

3.3. Scene-Modeling Principles and the Composition of 35 Situational Images

3.4. Phase 2 Questionnaire: Unified Situations, Unified Scales, and Response Flow

3.5. Sampling Frame, Ethics, and Reproducibility Essentials

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Pilot Testing and Measurement Quality of the Scale Architecture

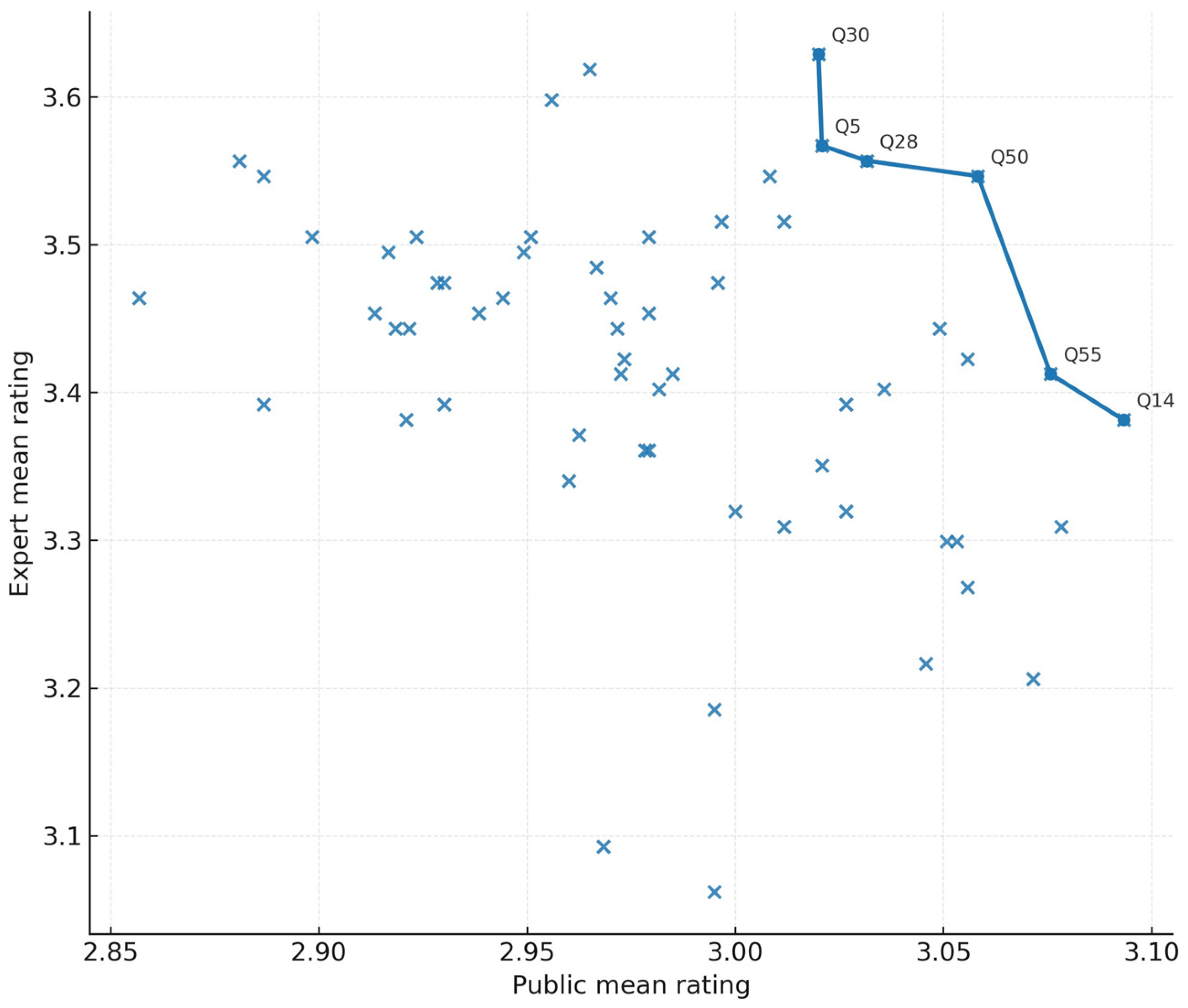

4.2. Core Relationships in Stage 1 (Public vs. Experts): Preference Structure and a Shared, “Governable” Vocabulary

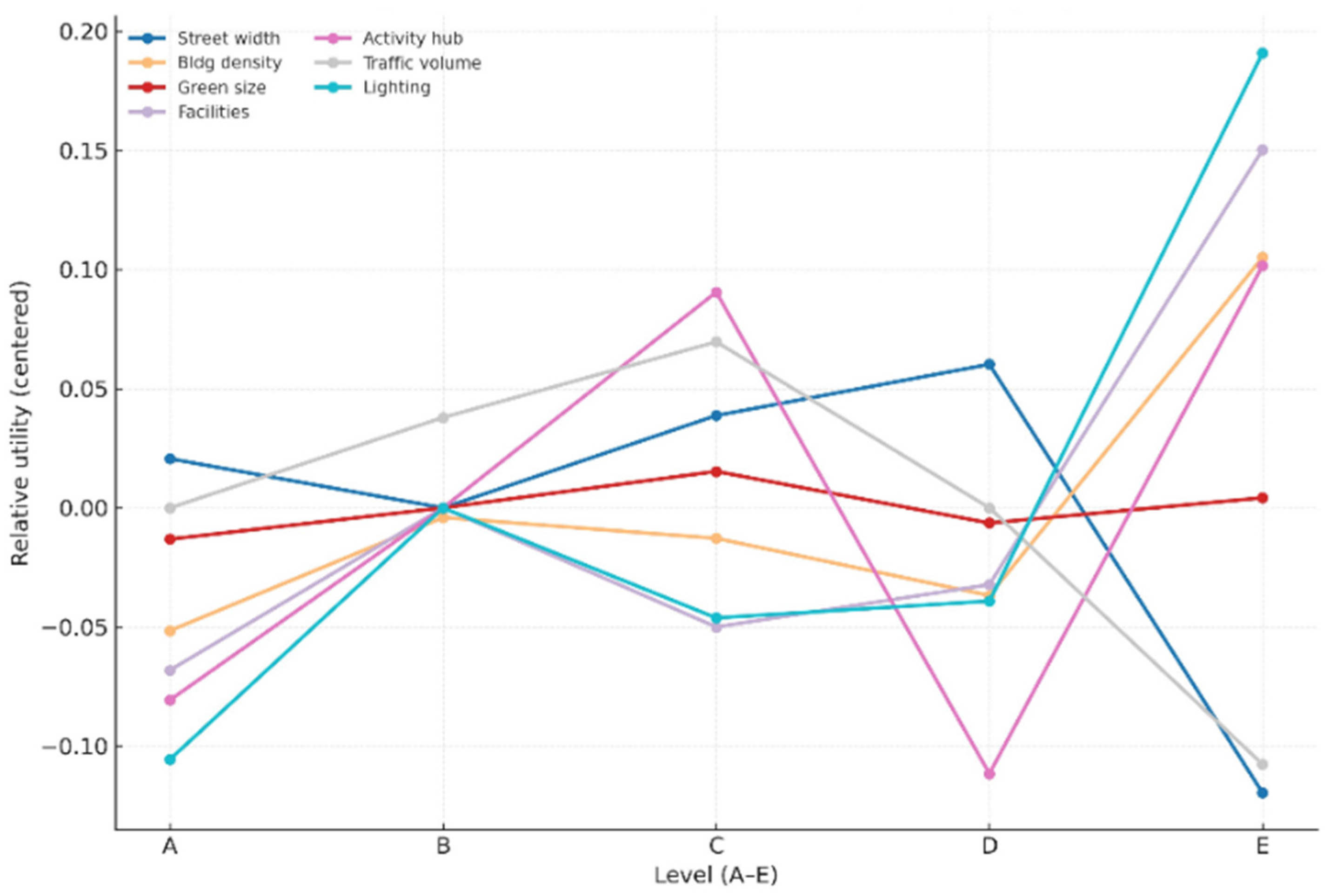

4.3. Stage 2 Scenario Preferences: Attribute–Gradient Functions, Thresholds, and Group Differences

4.4. Mediation by Sense of Place: The Causal Chain from Physical Cues to Adoption and Collaboration

4.5. An Integrative Account and New Insights into Resilient Landscapes

5. Conclusions and Outlook

5.1. Theoretical and Methodological Contributions

5.2. Limitations and Solvable Paths

5.3. Ten Directions for Future Research and Governance Translation

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Section | Construct | Sub- Dimensions | Items (n) | Reverse -Coded (n) | Response Scale | Anchors | Item Wording Cues (Examples) | Measurement Purpose | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (Shared) | Place attachment (spirit of place) | Identity; Dependence; Belonging | 9 | 3 | 5-point Likert (1–5) | Strongly disagree → Strongly agree | Belonging; reliance on local spaces; identification with street character | Mediator between design cues and civic action | Polarity- balanced; randomized items |

| A (Shared) | Perceived accessibility and continuity | Route continuity; Interface legibility; Wayfinding | 8 | 2 | 5-point Likert (1–5) | Strongly disagree → Strongly agree | Easy to reach daily destinations; continuous façades; visible entrances | Daily usability and micro-scale coherence | Includes a cross-check on detours |

| A (Shared) | Safety and nighttime visibility | Natural surveillance; Guardianship; Glare tolerance | 6 | 2 | 5-point Likert (1–5) | Strongly disagree → Strongly agree | Feel safe at night; light helps recognition; excessive brightness uncomfortable (R) | Links lighting with reassurance | Avoids legal wording |

| A (Shared) | Thermal comfort and shade | Shade availability; Radiant exposure; Resting opportunities | 6 | 2 | 5-point Likert (1–5) | Strongly disagree → Strongly agree | Enough shade to walk/rest; surfaces reduce heat; shaded seating | Proxy for heat-risk mitigation | Neutral-season phrasing |

| A (Shared) | Governance and maintainability | Cleanliness; Upkeep effort; Failure tolerance | 4 | 1 | 5-point Likert (1–5) | Strongly disagree → Strongly agree | Furniture easy to maintain; serviceable lighting; clutter prevention | Translates to operations constraints | Paired with reverse statement on over- equipment |

| A (Shared) | Adoption and participation willingness | Self-efficacy; Co-maintenance intention | 2 | 0 | 5-point Likert (1–5) | Strongly disagree → Strongly agree | Willing to co-maintain; willing to report failures | Bridge from perception to action | Short to avoid social desirability buildup |

| B (Public—short) | Use preference and satisfaction | Walkability; Rest/play; Visual comfort | 6 | 1 | 5-point Likert (1–5) | Strongly disagree → Strongly agree | Choose this route daily; stay comfortably | Utilitarian vs. amenity choices | Placed after A to reduce anchoring |

| B (Public—short) | Trade-offs of safety/ comfort | Lighting; Shade; Width priorities | 5 | 2 | 5-point Likert (1–5) | Strongly disagree → Strongly agree | Prefer stronger lighting even with glare (R); prefer more shade even if narrower | Elicits marginal preferences | Mirror- polarity pairs |

| B (Public—short) | Design levers quick rating | Seven levers cues (1–7) | 4 | 0 | 5-point Likert (1–5) | Very low → Very high | Width; density; green; facilities; activity hub; traffic; lighting | Priority snapshot | Scattered among other items |

| B (Expert—deep) | Lighting engineering preferences | Distribution; CCT; Uniformity; Glare; Mounting | 7 | 1 | 5-point Likert (1–5) | Strongly disagree → Strongly agree | Prefer uniformity over peak; avoid high-CCT spill; cutoff optics | Controllable parameters | Terminology aligned with practice |

| B (Expert—deep) | Street- canyon geometry and thermal thresholds | H/W; SVF; Albedo | 6 | 1 | 5-point Likert (1–5) | Strongly disagree → Strongly agree | Narrow canyons need trees; mid-albedo reduces MRT | Links geometry to microclimate | No simulation jargon in stems |

| B (Expert—deep) | Traffic exposure management | Speed; Volume; Separation; Crossings | 6 | 1 | 5-point Likert (1–5) | Strongly disagree → Strongly agree | Lower operating speed over added width; prioritize separation near schools | Casualty -risk proxies | Avoids enforcement phrasing |

| B (Expert—deep) | Facility density and operations risk | Clutter; Visibility; Maintenance cycles | 6 | 2 | 5-point Likert (1–5) | Strongly disagree → Strongly agree | Too many benches cause clutter (R); multi-use units cut upkeep | Amenity vs. order balance | Pairs with governance constructs |

| Item | Averages | Standard Deviation | Project-Total Score Correlation | α After Deleting This Question |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q01 | 3.978 | 0.763 | 0.196 | 0.763 |

| Q02 | 3.98 | 0.768 | 0.203 | 0.762 |

| Q03 | 3.967 | 0.787 | 0.208 | 0.762 |

| Q04 | 3.983 | 0.779 | 0.172 | 0.763 |

| Q05 | 3.967 | 0.77 | 0.212 | 0.762 |

| Q06 | 3.953 | 0.777 | 0.185 | 0.763 |

| Q07 | 2.03 | 0.35 | −0.021 | 0.767 |

| Q08 | 3.974 | 0.779 | 0.172 | 0.763 |

| Q09 | 3.978 | 0.777 | 0.218 | 0.762 |

| Q10 | 3.985 | 0.766 | 0.202 | 0.762 |

| Q11 | 4.075 | 0.751 | 0.228 | 0.761 |

| Q12 | 4.07 | 0.761 | 0.237 | 0.761 |

| Q13 | 4.071 | 0.748 | 0.232 | 0.761 |

| Q14 | 4.045 | 0.753 | 0.253 | 0.76 |

| Q15 | 4.056 | 0.754 | 0.226 | 0.761 |

| Q16 | 4.04 | 0.751 | 0.228 | 0.761 |

| Q17 | 4.078 | 0.745 | 0.229 | 0.761 |

| Q18 | 4.062 | 0.75 | 0.207 | 0.762 |

| Q19 | 4.078 | 0.744 | 0.235 | 0.761 |

| Q20 | 4.073 | 0.757 | 0.229 | 0.761 |

| Q21 | 4.094 | 0.757 | 0.184 | 0.763 |

| Q22 | 4.075 | 0.764 | 0.151 | 0.764 |

| Q23 | 4.098 | 0.767 | 0.168 | 0.764 |

| Q24 | 4.075 | 0.768 | 0.19 | 0.763 |

| Q25 | 4.108 | 0.751 | 0.173 | 0.763 |

| Q26 | 4.108 | 0.764 | 0.182 | 0.763 |

| Q27 | 4.088 | 0.763 | 0.197 | 0.762 |

| Q28 | 4.107 | 0.762 | 0.204 | 0.762 |

| Q29 | 3.925 | 0.803 | 0.187 | 0.763 |

| Q30 | 3.918 | 0.794 | 0.207 | 0.762 |

| Q31 | 3.91 | 0.806 | 0.211 | 0.762 |

| Q32 | 3.939 | 0.812 | 0.211 | 0.762 |

| Q33 | 3.912 | 0.824 | 0.195 | 0.763 |

| Q34 | 3.913 | 0.803 | 0.185 | 0.763 |

| Q35 | 3.918 | 0.814 | 0.213 | 0.762 |

| Q36 | 4.143 | 0.728 | 0.265 | 0.76 |

| Q37 | 4.161 | 0.714 | 0.279 | 0.76 |

| Q38 | 4.075 | 0.746 | 0.269 | 0.76 |

| Q39 | 4.045 | 0.731 | 0.265 | 0.76 |

| Q40 | 4.149 | 0.724 | 0.271 | 0.76 |

| Q41 | 4.117 | 0.729 | 0.274 | 0.76 |

| Q42 | 4.057 | 0.742 | 0.237 | 0.761 |

| Q43 | 4.076 | 0.738 | 0.244 | 0.761 |

| Q44 | 4.11 | 0.728 | 0.273 | 0.76 |

| Q45 | 4.141 | 0.718 | 0.239 | 0.761 |

| Q46 | 4.045 | 0.732 | 0.29 | 0.759 |

| Q47 | 4.044 | 0.729 | 0.271 | 0.76 |

| Q48 | 4.073 | 0.735 | 0.285 | 0.759 |

| Q49 | 4.121 | 0.739 | 0.268 | 0.76 |

References

- Iungman, T.; Cirach, M.; Marando, F.; Pereira Barboza, E.; Khomenko, S.; Masselot, P.; Quijal-Zamorano, M.; Mueller, N.; Gasparrini, A.; Urquiza, J.; et al. Cooling Cities through Urban Green Infrastructure: A Health Impact Assessment of European Cities. Lancet 2023, 401, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Svenning, J.-C.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, K.; Abrams, J.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Ripple, W.J.; Yu, Z.; Teng, S.N.; Dunn, R.R.; et al. Green Spaces Provide Substantial but Unequal Urban Cooling Globally. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahern, J. From Fail-Safe to Safe-to-Fail Sustainability and Resilience in the New Urban World. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 341–343. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1703085 (accessed on 22 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ferrario, F.; Mourato, J.M.; Rodrigues, M.S.; Dias, L.F. Evaluating Nature-Based Solutions as Urban Resilience and Climate Adaptation Tools: A Meta-Analysis of Their Benefits on Heatwaves and Floods. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 950, 175179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Debele, S.; Khalili, S.; Halios, C.H.; Sahani, J.; Aghamohammadi, N.; de Fatima Andrade, M.; Athanassiadou, M.; Bhui, K.; Calvillo, N.; et al. Urban Heat Mitigation by Green and Blue Infrastructure: Drivers, Effectiveness, and Future Needs. Innovation 2024, 5, 100588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining Place Attachment: A Tripartite Organizing Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohsari, M.J.; Yasunaga, A.; Oka, K.; Nakaya, T.; Nagai, Y.; McCormack, G.R. Place Attachment and Walking Behaviour: Mediation by Perceived Neighbourhood Walkability. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 235, 104767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahnow, R. Place Type or Place Function: What Matters for Place Attachment? Am. J. Community Psychol. 2023, 73, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Handy, S. Measuring the Unmeasurable: Urban Design Qualities Related to Walkability. J. Urban Des. 2009, 14, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, A.; Cohen, A.; Nelson, T.; Plaut, P. Evaluating the Relationship between Walking and Street Characteristics Based on Big Data and Machine Learning Analysis. Cities 2024, 151, 105111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mushayt, N.S.; Dal Cin, F.; Barreiros Proença, S. New Lens to Reveal the Street Interface. A Morphological-Visual Perception Methodological Contribution for Decoding the Public/Private Edge of Arterial Streets. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Erpecum, C.-P.L.; Bornioli, A.; Cleland, C.; Jones, S.; Davis, A.; den Braver, N.R.; Pilkington, P. 20 Mph Speed Limits: A Meta-Narrative Evidence Synthesis of the Public Health Evidence; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; Volume 13, pp. 167–195. [Google Scholar]

- Shrinivas, V.; Bastien, C.; Davies, H.; Daneshkhah, A.; Hardwicke, J. Parameters Influencing Pedestrian Injury and Severity–A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transp. Eng. 2023, 11, 100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, D.; Im, B.; Her, J.; Park, W.; Kang, S.-J.; Kim, S.-N. Street Lighting Environment and Fear of Crime: A Simulated Virtual Reality Experiment. Virtual Real. 2024, 29, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.E.; Bushover, B.; Mehranbod, C.A.; Gobaud, A.N.; Fish, C.; Eschliman, E.L.; Gao, X.; Zadey, S.; Morrison, C.N. Physical Environmental Roadway Interventions and Injury and Death for Vulnerable Road Users: A Natural Experiment in New York City. Inj. Prev. 2024, 31, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhaninia, S. The Social Cohesion Measures Contributing to Resilient Disaster Recovery: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Lit. 2024, 39, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, X.; Jian, I.Y.; Zhang, E.; Hou, Y.; Michael, W.; Li, Y. Community Resilience in City Emergency: Exploring the Roles of Environmental Perception, Social Justice and Community Attachment in Subjective Well-Being of Vulnerable Residents. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 97, 104745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining Urban Resilience: A Review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Burton, C.G.; Emrich, C.T. Disaster Resilience Indicators for Benchmarking Baseline Conditions. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2010, 7, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S.; Shaw, K.; Haider, L.J.; Quinlan, A.E.; Peterson, G.D.; Wilkinson, C.; Fünfgeld, H.; McEvoy, D.; Porter, L.; Davoudi, S. Resilience: A Bridging Concept or a Dead End? “Reframing” Resilience: Challenges for Planning Theory and Practice Interacting Traps: Resilience Assessment of a Pasture Management System in Northern Afghanistan Urban Resilience: What Does It Mean in Planning Practice? Resilience as a Useful Concept for Climate Change Adaptation? The Politics of Resilience for Planning: A Cautionary Note. Plan. Theory Pract. 2012, 13, 299–333. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/chapter/chapter-6 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Kabisch, N.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Hansen, R. Principles for Urban Nature-Based Solutions. Ambio 2022, 51, 1388–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodadad, M.; Aguilar-Barajas, I.; Khan, A.Z. Green Infrastructure for Urban Flood Resilience: A Review of Recent Literature on Bibliometrics, Methodologies, and Typologies. Water 2023, 15, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A. A Critical Review of Selected Tools for Assessing Community Resilience. Available online: https://www.apn-gcr.org/publication/a-critical-review-of-selected-tools-for-assessing-community-resilience/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Sharifi, A. Urban Resilience Assessment: Mapping Knowledge Structure and Trends. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, B.S.; Stedman, R.C. A Comparative Analysis of Predictors of Sense of Place Dimensions: Attachment To, Dependence On, and Identification with Lakeshore Properties. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 79, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The Measurement of Place Attachment: Validity and Generalizability of a Psychometric Approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.T.; Mowen, A.J.; Tarrant, M. Linking Place Preferences with Place Meaning: An Examination of the Relationship between Place Motivation and Place Attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Raymond, C. The Relationship between Place Attachment and Landscape Values: Toward Mapping Place Attachment. Appl. Geogr. 2007, 27, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Graham Smith, L.D.; Weiler, B. Testing the Dimensionality of Place Attachment and Its Relationships with Place Satisfaction and Pro-Environmental Behaviours: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.I.; Lee, K.J.; Larson, L.R. Place Attachment Mediates Links between Pro-Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors among Visitors to Mt. Bukhan National Park, South Korea. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1338650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, D.P.; Meyer, M.A. Social Capital and Community Resilience. Am. Behav. Sci. 2015, 59, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.S.; Rogers, M.B.; Amlot, R.; Rubin, G.J. What Do We Mean by “Community Resilience”? A Systematic Literature Review of How It Is Defined in the Literature. PLoS Curr. Disasters 2017, 9, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; de Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twohig-Bennett, C.; Jones, A. The Health Benefits of the Great Outdoors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Greenspace Exposure and Health Outcomes. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallemant, D.; Hamel, P.; Balbi, M.; Lim, T.N.; Schmitt, R.; Win, S. Nature-Based Solutions for Flood Risk Reduction: A Probabilistic Modeling Framework. One Earth 2021, 4, 1310–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, E.; Thorne, C.; Ahilan, S.; Arthur, S.; Birkinshaw, S.; Butler, D.; Dawson, D.; Everett, G.; Fenner, R.; Glenis, V.; et al. The Blue-Green Path to Urban Flood Resilience. Blue-Green Syst. 2019, 2, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ye, S.; Bai, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Sergey Ablameyko, S. Intelligent Mining of Urban Ventilation Corridors Based on High-Precision Oblique Photographic Images. Sensors 2021, 21, 7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, M.; Huang, H. The Synergistic Effect of Urban Canyon Geometries and Greenery on Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Humid Subtropical Climates. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 851810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheval, S.; Amihăesei, V.; Chitu, Z.; Dumitrescu, A.; Falcescu, V.; Irasoc, A.; Micu, D.; Mihulet, M.; Ontel, I.; Paraschiv, M.G.; et al. A Systematic Review of Urban Heat Island and Heat Waves Research (1991–2022). Clim. Risk Manag. 2024, 44, 100603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middel, A.; Selover, N.; Hagen, B.; Chhetri, N. Impact of Shade on Outdoor Thermal Comfort—A Seasonal Field Study in Tempe, Arizona. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2016, 60, 1849–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . Grundy, C.; Steinbach, R.; Edwards, P.; Green, J.; Armstrong, B.; Wilkinson, P. Effect of 20 Mph Traffic Speed Zones on Road Injuries in London, 1986–2006: Controlled Interrupted Time Series Analysis. BMJ 2009, 339, b4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, F.; Collier, T.; Frost, C.; Ker, K.; Steinbach, R.; Roberts, I.; Wentz, R. Area-Wide Traffic Calming for Preventing Traffic Related Injuries. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2003, 2010, cd003110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namatovu, S.; Balugaba, B.E.; Muni, K.; Ningwa, A.; Nsabagwa, L.; Oporia, F.; Kiconco, A.; Kyamanywa, P.; Mutto, M.; Osuret, J.; et al. Interventions to Reduce Pedestrian Road Traffic Injuries: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials, Cluster Randomized Controlled Trials, Interrupted Time-Series, and Controlled Before-after Studies. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotios, S.; Unwin, J.; Farrall, S. Road Lighting and Pedestrian Reassurance after Dark: A Review. Light. Res. Technol. 2014, 47, 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, B.C.; Farrington, D.P. Effects of Improved Street Lighting on Crime. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2008, 4, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falchi, F.; Cinzano, P.; Duriscoe, D.; Kyba, C.C.M.; Elvidge, C.D.; Baugh, K.; Portnov, B.A.; Rybnikova, N.A.; Furgoni, R. The New World Atlas of Artificial Night Sky Brightness. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1600377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jägerbrand, A.K.; Bouroussis, C.A. Ecological Impact of Artificial Light at Night: Effective Strategies and Measures to Deal with Protected Species and Habitats. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haans, A.; de Kort, Y.A.W. Light Distribution in Dynamic Street Lighting: Two Experimental Studies on Its Effects on Perceived Safety, Prospect, Concealment, and Escape. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennie, J.; Davies, T.W.; Cruse, D.; Inger, R.; Gaston, K.J. Cascading Effects of Artificial Light at Night: Resource-Mediated Control of Herbivores in a Grassland Ecosystem. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kessel, G.; Milanese, S.; Dizon, J.; de Vries, D.H.; MacGregor, H.; Abramowitz, S.; Enria, L.; Burtscher, D.; Yeoh, E.-K.; Thomas, B.E.; et al. Community Resilience to Health Emergencies: A Scoping Review. BMJ Glob. Health 2025, 10, e016963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjerde, M. Visual Evaluation of Urban Streetscapes: How Do Public Preferences Reconcile with Those Held by Experts? Urban Des. Int. 2011, 16, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najar, K.; Nylander, O.; Woxnerud, W. Public’s Visual Preferences Survey Facilitates Community-Based Design and Color Standards Creation. Buildings 2024, 14, 2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasser, E.; Lavdas, A.A. Uta Schirpke Assessing Landscape Aesthetic Values: Do Clouds in Photographs Influence People’s Preferences? PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macháč, J.; Brabec, J.; Arnberger, A. Exploring Public Preferences and Preference Heterogeneity for Green and Blue Infrastructure in Urban Green Spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 75, 127695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirpke, U.; Mölk, F.; Feilhauer, E.; Tappeiner, U.; Tappeiner, G. How Suitable Are Discrete Choice Experiments Based on Landscape Indicators for Estimating Landscape Preferences? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 237, 104813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dongen, R.P.; Timmermans, H.J.P. Preference for Different Urban Greenscape Designs: A Choice Experiment Using Virtual Environments. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 44, 126435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Handy, S.; Brownson, R.C.; Clemente, O.; Winston, E. Identifying and Measuring Urban Design Qualities Related to Walkability. J. Phys. Act. Health 2006, 3, S223–S240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zeng, L.; Liang, H.; Li, D.; Yang, X.; Zhang, B. Comprehensive Walkability Assessment of Urban Pedestrian Environments Using Big Data and Deep Learning Techniques. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Clemente, O.; Neckerman, K.M.; Purciel-Hill, M.; Quinn, J.W.; Rundle, A. Measuring Urban Design; Island Press/Center for Resource Economics: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 9781597263672. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi Farahani, L.; Maller, C.J. Perceptions and Preferences of Urban Greenspaces: A Literature Review and Framework for Policy and Practice. Landsc. Online 2018, 61, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, W.; Pickett, S.T.; Qian, Y. A Scaling Law for Predicting Urban Trees Canopy Cooling Efficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2401210121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; He, L.; Wennberg, P.O.; Frankenberg, C. Unequal Exposure to Heatwaves in Los Angeles: Impact of Uneven Green Spaces. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade8501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillerot, L.; Landuyt, D.; de Frenne, P.; Muys, B.; Verheyen, K. Urban Tree Canopies Drive Human Heat Stress Mitigation. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 92, 128192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himschoot, E.A.; Crump, M.C.; Buckley, S.; Cai, C.; Lawson, S.; White, J.; Beeco, A.; Taff, D.B.; Newman, P. Feelings of Safety for Visitors Recreating Outdoors at Night in Different Artificial Lighting Conditions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 97, 102374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Y. Smart Cities Net Zero Planning Considering Renewable Energy Landscape Design in Digital Twin. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 63, 103629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iungman, T.; Khomenko, S.; Barboza, E.P.; Cirach, M.; Gonçalves, K.; Petrone, P.; Erbertseder, T.; Taubenböck, H.; Chakraborty, T.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M. The Impact of Urban Configuration Types on Urban Heat Islands, Air Pollution, CO2 Emissions, and Mortality in Europe: A Data Science Approach. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e489–e505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trop, T.; Shoshany Tavory, S.; Portnov, B.A. Factors Affecting Pedestrians’ Perceptions of Safety, Comfort, and Pleasantness Induced by Public Space Lighting: A Systematic Literature Review. Environ. Behav. 2023, 55, 3–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalvandi, R.; Karimimoshaver, M. The Optimal Ratio in the Street Canyons: Comparison of Two Methods of Satellite Images and Simulation. Build. Environ. 2023, 229, 109927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Razik, M.M.; Hafez, Y.K.; Hendy, A.H.; Fawzy, M.M. Methodology for Microclimatic Urban Canyon Design Case Study Surrounding MUST University Campus in Cairo. HBRC J. 2024, 20, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghibi, M. Rethinking Small Vacant Lands in Urban Resilience: Decoding Cognitive and Emotional Responses to Cityscapes. Cities 2024, 151, 105167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.I.; Biswas, T.; Chakraborty, T.C.; Kroeger, T.; Cook-Patton, S.C.; Fargione, J.E. Current Inequality and Future Potential of US Urban Tree Cover for Reducing Heat-Related Health Impacts. npj Urban Sustain. 2024, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, C.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Carmeliet, J.; Bardhan, R. Cooling Efficacy of Trees across Cities Is Determined by Background Climate, Urban Morphology, and Tree Trait. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, E.; Schifanella, R.; Piccardo, M.; Caporaso, L.; Taubenböck, H.; Cescatti, A.; Duveiller, G. Spatially-Optimized Urban Greening for Reduction of Population Exposure to Land Surface Temperature Extremes. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete-Hernandez, P.; Luneke, A.; Truffello, R.; Fuentes, L. Planning for Fear of Crime Reduction: Assessing the Impact of Public Space Regeneration on Safety Perceptions in Deprived Neighborhoods. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 237, 104809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor Code | Factor Label | Gradient Definition (A→E) | Level A | Level B | Level C | Level D | Level E | Controlled Conditions (Held Constant) | Targeted Proxy Indicators | Parameter Anchors (Design- Time) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Street width (canyon ratio) | Widens A→E; height fixed; camera/sky/ materials held constant | A: very narrow (H/W ≈ 2.5) | B: narrow (≈2.0) | C: moderate (≈1.5) | D: wide (≈1.0) | E: very wide (≈0.5) | 50 mm lens; eye 1.6 m; constant HDR sky; constant façades/ pavement | Walkability continuity; sightlines; thermal exposure | Building height ~15 m; mid-albedo pavement |

| 2 | Building density (site coverage) | Decreases A→E; width fixed | A: ≈70% | B: ≈60% | C: ≈50% | D: ≈40% | E: ≈30% | Massing/setbacks adjusted; skyline unchanged | Daylight; airflow; openness; emergency clearance | Façade rhythm kept; ground- floor permeability unchanged |

| 3 | Green area size (canopy cover) | Increases A→E with trees dominant; path width fixed | A: ≈5% | B: ≈12% | C: ≈20% | D: ≈30% | E: ≈45% | Species and crown shapes consistent; planters vs. in-ground constant | Thermal mitigation; rest willingness; biophilic appraisal | Tree height ≈ 7–9 m; minimal understory |

| 4 | Facilities and equipment density | Increases A→E; clear routes intact | A: ≤1/50 m | B: 1–2/50 m | C: 3–4/50 m | D: 5–6/50 m | E: ≥7/50 m | Same furniture family/palette; barrier-free kept | Comfortable to stay; order vs. clutter; visibility; upkeep complexity | Clear path ≥ 1.2 m; mounting method constant |

| 5 | Activity hub area | Increases A→E; circulation rings open | A: 0 m2 | B: 150 m2 | C: 300 m2 | D: 500 m2 | E: 800 m2 | Surface finish/edges constant; no event props | Interaction capacity; event readiness; noise spill risk | Drainage slope constant; no fencing change |

| 6 | Traffic flow intensity | Increases A→E; lane geometry fixed | A: car-free | B: ≈2/min | C: ≈5/min | D: ≈9/min | E: ≥15/min | Same lane width/markings; crossings constant; no parking change | Risk/noise/pollution exposure; liveliness; crossing stress | Operating speed placeholder 20–40 km/h |

| 7 | Street lighting (coverage/ distribution) | Increases illuminance and uniformity A→E; mast spacing stable | A: Eh ≈ 2 lx; Uo ≈ 0.20; 2700 K | B: 5 lx; 0.30; 3000 K | C: 10 lx; 0.40; 3500 K | D: 15 lx; 0.50; 4000 K | E: 25 lx; 0.60; 4000 K (glare risk) | Ambient sky constant; luminaire model and height fixed; spill-controlled | Night reassurance; facial recognition; glare comfort; biodiversity risk | Backlight cutoff; CRI ≈ 70–80; no dynamic dimming |

| Group and Phase | Administration Mode | Inclusion Criteria | Quota Dimensions | Quota Targets (Examples) | Planned Sample and Rotation | Stimulus Blocking and Ordering | Embedded Quality Controls | Additional QC Rules | Consent and Privacy | Governance Weighting (Design) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public—Phase 1 | Online self- administered | Adults (18+); regular street users; can view images on desktop/ mobile | City size; street type; built-year period | Tier 1/2 cities balanced; main/ secondary streets; pre-2000 vs. post-2000 | Target N ≈ 3200; randomized seeds per block | Blocks of 7–10 items; interleaved factors; no consecutive A–E set | 2 attention checks; 2 semantic- consistency pairs; mirrored polarity | Time- per-page threshold; straight- lining flags | Consent screen; anonymized storage; no uploads | Design statement: κp = αp·τp for synthesis |

| Expert—Phase 1 | Online supervised invitation | Professionals in planning/ landscape/ transport/ lighting/ public safety/ community | Discipline; years of practice; project exposure | Even split across six disciplines; ≥3 years practice; recent projects required | Target N ≈ 180; balanced by discipline | Blocks of 7–10 items; expert deep section appended | 2 attention checks; 2 consistency pairs; terminology glossary in stems | Same thresholds; identity verified by affiliation | Consent screen; anonymized storage; no uploads | Design statement: κe = αe·τe for synthesis |

| Public—Phase 2 | Online self-administered | Adults (18+); able to judge 35 images; no color- vision issues self- reported | City size; street type; night- walking exposure | Even split by city size; ≥30% with weekly night walking | Target N ≈ 1000; stimuli evenly rotated | Image blocks randomized; factor order balanced | 2 attention checks; 2 consistency vignettes | Same thresholds; device type recorded | Consent screen; anonymized storage; no uploads | Design statement: κp used in governance weighting |

| Expert—Phase 2 | Online supervised invitation | Same disciplines as Phase 1; able to judge lighting/ traffic/ geometry cues | Discipline; role (designer/ engineer/ manager) | 1:1:1 across roles | Target N ≈ 100; balanced across roles | Same as Phase 2 public; deep terminology retained | 2 attention checks; polarity mirrors | Same as above | Consent screen; anonymized storage; no uploads | Design statement: κe used in governance weighting |

| Scale | Items_ Planned | Items_Used_ for_Stats | Dropped_ Items | Valid_ Sample_Size | Cronbach_ Alpha | KMO_Overall | Bartlett_Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section A (Foundational constructs) | 35 | 35 | 0 | 3176 | 0.748 | N/A | N/A |

| Section B (Governance and operability, brief) | 15 | 15 | 0 | 3176 | 0.839 | N/A | N/A |

| Combined A + B (final instrument) | 50 | 49 | 1 | 3176 | 0.765 | 0.911 | χ2 = 33,831.23; = 1176; p < 0.001 |

| Factor | Conceptual Label | Eigenvalue | Variance Explained (%) | Assigned Items (n) | Top Loadings (Item|λ) | Cronbach’s Alpha | Median Communality | Max Cross-Loading (abs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Place attachment and identity | 9.22 | 18.21 | 14 | A12|0.82; A21|0.79; A07|0.77; A28|0.74 | 0.912 | 0.61 | 0.28 |

| F2 | Accessibility and safety | 5.87 | 11.59 | 12 | A03|0.76; A15|0.73; B04|0.71; A26|0.70 | 0.884 | 0.55 | 0.26 |

| F3 | Governance and maintenance | 3.74 | 7.38 | 11 | B09|0.78; B12|0.75; A24|0.71; B06|0.69 | 0.861 | 0.49 | 0.25 |

| F4 | Adoption and participation | 2.96 | 5.84 | 12 | B02|0.74; A18|0.71; B14|0.70; A33|0.68 | 0.846 | 0.47 | 0.24 |

| Attribute | Public_Best | Public_Shape | Expert_Best | Expert_Shape | Bridge_a | Bridge_ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Street width | E (μ = 3.021) | Irregular | E (μ = 3.567) | Irregular | 0.437 | 0.563 |

| 2. Building density | E (μ = 3.049) | Monotonic+ | B (μ = 3.495) | Irregular | 0.437 | 0.563 |

| 3. Green area size | D (μ = 3.093) | Irregular | C (μ = 3.454) | Inverted-U, L* ≈ 3 | 0.437 | 0.563 |

| 4. Facilities and equipment | C (μ = 3.046) | Irregular | D (μ = 3.351) | Irregular | 0.437 | 0.563 |

| 5. Public activity area | D (μ = 3.012) | Inverted-U, L* ≈ 4 | B (μ = 3.619) | Irregular | 0.437 | 0.563 |

| 6. Traffic flow and access | D (μ = 3.056) | Inverted-U, L* ≈ 4 | E (μ = 3.629) | Irregular | 0.437 | 0.563 |

| 7. Lighting | E (μ = 2.938) | Irregular | D (μ = 3.495) | Irregular | 0.437 | 0.563 |

| Attribute | Public_ Best_ Form | Public_ Pattern | Public_ L* | Public_ Delta AIC | Expert_ Best_ Form | Expert_ Pattern | Expert_ L* | Expert_ Delta AIC | Δslope (Exp− Pub) | p_Diff | q_Diff (FDR) | Public_ Opt_ Level (1–5) | Expert_ Opt_ Level (1–5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Street width | Linear | Monotonic | – | 0 | Linear | Monotonic | – | 0 | 0.053 | 9.256 × 10−2 | 1.620 × 10−1 | 5 | 5 |

| 2. Building density | Linear | Monotonic | – | 0 | Linear | Monotonic | – | 0 | 0.058 | 2.836 × 10−2 | 6.617 × 10−2 | 1 | 5 |

| 3. Green area size | Linear | Monotonic | – | 0 | Linear | Monotonic | – | 0 | −0.109 | 4.413 × 10−6 | 2.222 × 10−5 | 5 | 1 |

| 4. Facilities and equipment | Threshold | Hinge | 2 | 1.244 | Linear | Monotonic | – | 0 | −0.005 | 8.135 × 10−1 | 8.135 × 10−1 | 5 | 1 |

| 5. Activity center size | Threshold | Hinge | 4 | 0.723 | Threshold | Hinge | 4 | 2.854 | −0.117 | 6.349 × 10−6 | 2.222 × 10−5 | 4 | 5 |

| 6. Traffic flow | Linear | Monotonic | – | 0 | Linear | Monotonic | – | 0 | −0.014 | 6.519 × 10−1 | 7.606 × 10−1 | 5 | 5 |

| 7. Lighting coverage | Linear | Monotonic | – | 0 | Linear | Monotonic | – | 0 | 0.016 | 5.555 × 10−1 | 7.606 × 10−1 | 5 | 5 |

| Attribute (X) | Mediator (M) | Group | a: X→M (β) | b: M→Y (β) | Indirect a × b | 95% CI (LL) | 95% CI (UL) | Direct c’ (β) | Total c (β) | Mediation Share (%) | Δχ2 (Group Diff) | p-Value | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lighting (D vs. C) | Perceived Safety | Public | 0.333 | 0.41 | 0.135 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.205 | 65.9 | 6.72 | 0.009 | 978 |

| Green Area (E vs. C) | Place Attachment | Public | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.101 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.161 | 62.7 | 5.88 | 0.015 | 978 |

| Traffic (Low vs. Mid) | Perceived Safety | Public | 0.22 | 0.38 | 0.084 | 0.052 | 0.117 | 0.05 | 0.134 | 62.7 | 7.41 | 0.006 | 978 |

| Facilities (D vs. C) | Place Dependence | Public | 0.19 | 0.29 | 0.055 | 0.028 | 0.082 | 0.046 | 0.101 | 54.5 | 3.96 | 0.047 | 978 |

| Lighting (D–E band) | Perceived Safety | Expert | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.078 | 0.04 | 0.116 | 0.11 | 0.188 | 41.5 | 6.72 | 0.009 | 91 |

| Green Area (D vs. C) | Place Attachment | Expert | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.053 | 0.02 | 0.085 | 0.08 | 0.133 | 39.8 | 5.88 | 0.015 | 91 |

| Traffic (Low vs. Mid) | Governance Belief | Expert | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.116 | 0.073 | 0.158 | 0.09 | 0.206 | 56.3 | 7.41 | 0.006 | 91 |

| Facilities (C vs. D) | Governance Belief | Expert | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.065 | 0.031 | 0.098 | 0.062 | 0.127 | 51.2 | 3.96 | 0.047 | 91 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Song, P.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, T.; Zhou, B. Translating Urban Resilience into Deployable Streetscapes: A Sense-of-Place–Mediated Measurement–Choice Framework with Threshold Identification. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 501. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120501

Wang J, Song P, Li Y, Zhang Y, Wu T, Zhou B. Translating Urban Resilience into Deployable Streetscapes: A Sense-of-Place–Mediated Measurement–Choice Framework with Threshold Identification. Urban Science. 2025; 9(12):501. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120501

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jiahe, Pufan Song, Yifei Li, Yalan Zhang, Tianbao Wu, and Biao Zhou. 2025. "Translating Urban Resilience into Deployable Streetscapes: A Sense-of-Place–Mediated Measurement–Choice Framework with Threshold Identification" Urban Science 9, no. 12: 501. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120501

APA StyleWang, J., Song, P., Li, Y., Zhang, Y., Wu, T., & Zhou, B. (2025). Translating Urban Resilience into Deployable Streetscapes: A Sense-of-Place–Mediated Measurement–Choice Framework with Threshold Identification. Urban Science, 9(12), 501. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9120501