Urban Dimensions and Indicators for Smart Tourist Destinations from a State of the Art

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Contextualization

1.2. Research Problem

1.3. Research Question

- (a)

- What are the main indicators and dimensions available in the literature that rate Smart Tourist Destinations?

- (b)

- Are the existing indicators sufficient to rate a Smart Tourist Destination, considering all the dimensions of a DTI?

1.4. Research Hypothesis

1.5. Objective

1.6. Justification of the Study for the Field of Tourism

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Characterization

2.2. Procedures for Data Collection

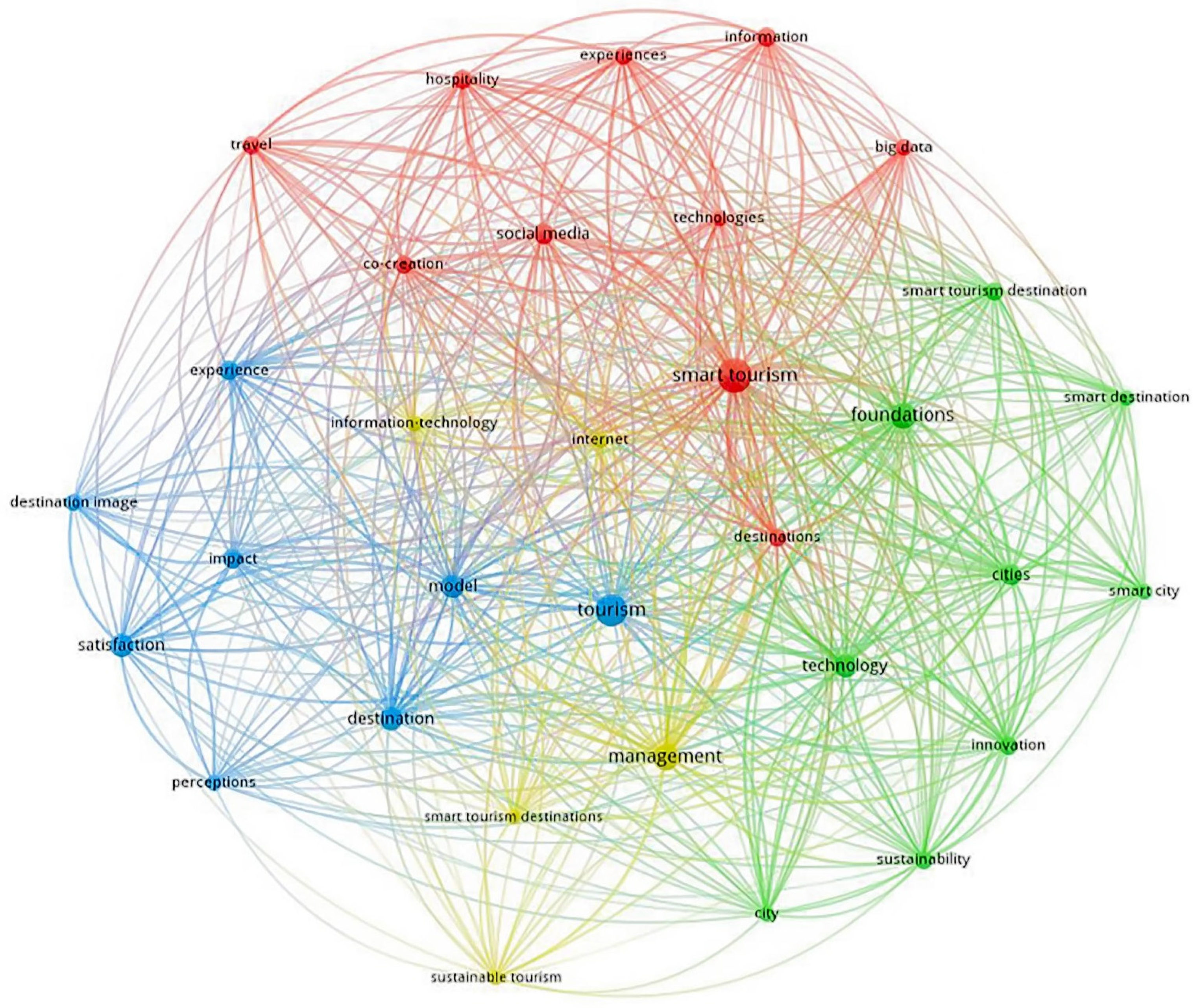

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Dimensions

3.1.1. Information and Communication Technologies (TICs)

3.1.2. Governance

3.1.3. Innovation

3.1.4. Accessibility

3.1.5. Performance

3.1.6. Mobility and Urban Infrastructure

3.1.7. Sustainability

3.1.8. Economic Sustainability

3.1.9. Social Sustainability

3.1.10. Environmental Sustainability

3.2. Indicators for Dimensions

3.2.1. Information and Communication Technology (TIC) Indicators

3.2.2. Governance Indicators

3.2.3. Innovation Indicators

3.2.4. Accessibility Indicators

3.2.5. Performance Indicators

3.2.6. Mobility and Urban Infrastructure Indicators

3.2.7. Sustainability Indicators

3.2.8. Economic Sustainability Indicators

3.2.9. Social Sustainability Indicators

3.2.10. Environmental Sustainability Indicators

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DTI | Smart Tourist Destination |

| TIC | Information and Communication Technology |

| SEGITTUR | Sociedad Mercantil Estatal para la Gestión de la Innovación y las Tecnologías Turísticas |

| INVAT.TUR | Instituto Valenciano de Tecnologías Turísticas |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| DMO | Destination Management Organizations |

| ROI | Return on Investment |

| WAI | Web Accessibility Initiative |

| RevPAR | Revenue Per Available Room |

| QR code | Quick Response Code |

| RFID | Radio-Frequency Identification |

| NFC | Near Field Communication |

| PCDs | People with Disabilities |

References

- Boes, K.; Buhalis, D.; Inversini, A. Smart tourism destinations: Ecosystems for tourism destination competitiveness. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2016, 2, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Sigala, M.; Xiang, Z.; Koo, C. Smart tourism: Foundations and developments. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEGITTUR; Andrades, L. The Technology Pillar of the Spanish Smart Tourism Destination (DTI) Model. In The Spanish Model for Smart Tourism Destination Management: A Methodological Approach; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 149–176. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-60709-7_6 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Kusumawardhani, Y.; Hilmiana, H.; Widianto, S.; Azis, Y. Smart tourism practice in the scope of sustainable tourism in emerging markets: A systematic literature review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 2384193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suanpang, P.; Pothipassa, P. Integrating generative AI and IoT for sustainable smart tourism destinations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hall, C.M.; Zhu, C.; Ting Pong Cheng, V. Redefining the concept of smart tourism in tourism and hospitality. Anatolia 2024, 35, 566–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivars-Baidal, J.; Celdrán-Bernabéu, M.A.; Femenia-Serra, F. Guía de Implantación de Destinos Turísticos Inteligentes de la Comunitat Valenciana. 2021. Available online: https://invattur.es/uploads/entorno_37/ficheros/62690c9e305de2073297352.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Xiang, Z.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Big data analytics, tourism design and smart tourism. In Analytics in Smart Tourism Design: Concepts and Methods; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Stienmetz, J.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Smart Tourism Design: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on designing tourism places. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 86, 103154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, N. Challenges, function changing of government and enterprises in Chinese smart tourism. Inf. Commun. Technol. Tour. 2014, 10, 553–564. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Li, X.R.; Zhen, F.; Zhang, J. How smart is your tourist attraction?: Measuring tourist preferences of smart tourism attractions via a FCEM-AHP and IPA approach. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, A.; Matika, V.; Nikas, I.A.; Paraschi, E.P. A comprehensive structural framework for smart stadiums as essential components of smart tourism destinations. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2025, 17, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, S.; Ghatari, A.R.; Hasanzadeh, A.; Jahanyan, S. Developing a model for sustainable smart tourism destinations: A systematic review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Werthner, H.; Koo, C.; Lamsfus, C. Conceptual foundations for understanding smart tourism ecosystems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.J.; Lemieux, C.J.; Malone, L. Climate services to support sustainable tourism and adaptation to climate change. Clim. Res. 2011, 47, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font-Barnet, A.; Ciurana, A.B.; Pozo, J.X.O.; Russo, A.; Coscarelli, R.; Antronico, L.; De Pascale, F.; Saladié, Ò.; Anton-Clavé, S.; Aguilar, E. Climate services for tourism: An applied methodology for user engagement and co-creation in European destinations. Clim. Serv. 2021, 23, 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, A.; Köberl, J.; Stegmaier, P.; Alonso, E.J.; Harjanne, A. The market for climate services in the tourism sector–An analysis of Austrian stakeholders’ perceptions. Clim. Serv. 2020, 17, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMT-ORGANIZAÇÃO MUNDIAL DO TURISMO. Digital Transformation. 2018. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/es/digital-transformation (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Alsharif, A.; Isa, S.M.; Alqudah, M.N. Smart tourism, hospitality, and destination: A systematic review and future directions. J. Tour. Serv. 2024, 15, 72–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Projeto de Pesquisa: Métodos Qualitativo, Quantitativo e Misto; Penso Editora: Porto Alegre, Brasil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sampieri, R.H.; Collado, C.F.; Lucio, M.P.B. Metodologia de Pesquisa; Penso Editora: Porto Alegre, Brasil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Junguitu, D.; Peña-Cerezo, M.A. Bibliomerge: A Python-Based Automated Tool to Merge Wos and Scopus Bibliographic Data, Compatible with Biblioshiny, Bibexcel, Vosviewer, Scimat and Scientopy. 2025. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5327967 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Zupic, I.; Čater, T. Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organ. Res. Methods 2015, 18, 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, L. Análisis de Contenido; Ediciones Akal: Madrid, Spain, 2011; Volume 89. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Wang, S.; Wu, W. Tourism industry shrinkage and the economic loss of China in the COVID pandemic years. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 28, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, C.; Rodrigues, P.; Gomez-Suarez, M. A bibliometric and content analysis of sustainability and smart tourism. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Oliva, A.; Alvarado-Uribe, J.; Parra-Meroño, M.C.; Jara, A.J. Transforming communication channels to the co-creation and diffusion of intangible heritage in smart tourism destination: Creation and testing in Ceutí (Spain). Sustainability 2019, 11, 3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allawi, A.H. Towards Smart Trends for Tourism Development and its Role in the Place Sustainability-Karbala Region, a Case Study. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2022, 17, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Júnior, A.; Almeida-García, F.; Morgado, P.; Mendes-Filho, L. Residents’ quality of life in smart tourism destinations: A theoretical approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes Filho, L.; Mayer, V.F.; Correa, C.H.W. Dimensões que influenciam a percepção dos turistas sobre Destinos Turísticos Inteligentes. Rev. Bras. Pesqui. Em Tur. 2022, 16, e-2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Júnior, A.; Mendes-Filho, L.; Almeida-García, F.; Manuel-Simões, J. Smart Tourism Destinations: Un estudio basado en lavisión de los stakeholders. Rev. Tur. Em Análise 2017, 28, 358–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- González-Reverté, F. Building sustainable smart destinations: An approach based on the development of Spanish smart tourism plans. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Woo, M.; Nam, K.; Chathoth, P.K. Smart city and smart tourism: A case of Dubai. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivars-Baidal, J.A.; Vera-Rebollo, J.F.; Perles-Ribes, J.; Femenia-Serra, F.; Celdrán-Bernabeu, M.A. Sustainable tourism indicators: What’s new within the smart city/destination approach? J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 1556–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges-Tiago, T.; Veríssimo, J.M.; Tiago, F. Smart tourism: A scientometric review (2008–2020). Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 30, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femenia-Serra, F.; Ivars-Baidal, J.A. Do smart tourism destinations really work? The case of Benidorm. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo Ortega, J.L.; Malcolm, C.D. Touristic stakeholders’ perceptions about the smart tourism destination concept in Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, Mexico. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Amaranggana, A. Smart tourism destinations enhancing tourism experience through personalisation of services. In Proceedings of the Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2015, Lugano, Switzerland, 3–6 February 2015; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, A.; Rodrigues, R.; Lopes, S.; Palrão, T. Exploring positive and negative emotions through motivational factors: Before, during, and after the pandemic crisis with a sustainability perspective. Sustainability 2023, 17, 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romão, J.; Nijkamp, P. Impacts of innovation, productivity and specialization on tourism competitiveness–a spatial econometric analysis on European regions. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1150–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivars-Baidal, J.A.; Celdrán-Bernabeu, M.A.; Femenia-Serra, F.; Perles-Ribes, J.F.; Vera-Rebollo, J.F. Smart city and smart destination planning: Examining instruments and perceived impacts in Spain. Cities 2023, 137, 104266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, A.; Zayas, A.; Gómez-Carmona, D.; Sánchez, J.A.L. Smart tourism destinations really make sustainable cities: Benidorm as a case study. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2022, 9, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B. Smart City Index Master Indicators Survey. 2014. Available online: https://www.smartcitiescouncil.com/ (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Buonincontri, P.; Micera, R. The experience co-creation in smart tourism destinations: A multiple case analysis of European destinations. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2016, 16, 285–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyusupov, B.; Khodjaniyazov, E.; Masharipova, M.; Gurbanov, F. The concepts of smart cities, smart tourism destination and smart tourism cities and their interrelationship. BIO Web Conf. 2024, 82, 06015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.Y.; Chen, C.D.; Ku, E.C. Enhancing smart tourism and smart city development: Evidence from Taoyuan smart aviation city in Taiwan. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2024, 10, 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Vega, P.M.; Domínguez, D.P.; Escobar, S.D. Smart Tourism Development Based on Governance and Technology. The Role of Creativity and Governance: Building Strength After Challenges, 43. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tania-Gonzalez-Alvarado-2/publication/392101221_The_role_of_creativity_and_governance-_building_strength_after_challenges/links/6834bd7a6b5a287c3045ab3d/The-role-of-creativity-and-governance-building-strength-after-challenges.pdf#page=49 (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Wang, H.R.; Fang, Y.; Shao, J.P.; Li, C. Digital Governance Driving Tourism Development: The Mediating Role of Tourism Resources and the Moderating Effect of Provincial Economic Comprehensive Competitiveness. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillakis, M.G.; Koutroulis, A.G.; Tsanis, I.K. The 2 C global warming effect on summer European tourism through different indices. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2016, 60, 1205–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, A.; Greuell, W.; Landgren, O.; Prettenthaler, F. Impacts of+ 2 C global warming on winter tourism demand in Europe. Clim. Serv. 2017, 7, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, A.D. Evaluating bibliometrics reviews: A practical guide for peer review and critical reading. Eval. Rev. 2025, 49, 1074–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chansanam, W.; Lai, C. KKU-BiblioMerge: A novel tool for multi-database integration in bibliometric analysis. Iberoam. J. Sci. Meas. Commun. 2025, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, D.R. Assessing scholarly impact: Conducting bibliometric analyses. In Handbook of Research Methods in Social Work; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2025; pp. 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Matorevhu, A. Bibliometrics: Application opportunities and limitations. In Bibliometrics-An Essential Methodological Tool for Research Projects; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://books.google.com.br/books?hl=pt-BR&lr=&id=G9U3EQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA3&dq=limits+of+bibliometrics&ots=bKyPnsZbrK&sig=6a_mh8aOkMV0z3gCUScfayJB09E#v=onepage&q=limits%20of%20bibliometrics&f=false (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Amiruddin, M.Z.B.; Samsudin, A.; Suhandi, A.; Coştu, B.; Prahani, B.K. Scientific mapping and trend of conceptual change: A bibliometric analysis. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 11, 101208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Unit of Record (Found) | Authors (Cite as Dimension) | Context Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Information and Communication Technologies (TICs) (Connectivity/Information System) | GOMEZ-OLIVA, A. et al. (2019) [27]; ALLAWI, A. H. (2022) [28]; SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2020) [29]; MENDES FILHO, L. et al. (2022) [30]; SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2017) [31]; GONZÁLEZ-REVERTÉ, F. (2019) [32]; KHAN, M. S. et al. (2017) [33]; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2021) [7]; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2023) [34]; BOES, K.; BUHALIS, D.; INVERSINI, A. (2015) [1]; BORGES-TIAGO, T.; VERÍSSIMO, J.; TIAGO, F. (2022) [35]; FEMENIA-SERRA, F.; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. (2021) [36]; CORNEJO ORTEGA, J. L.; MALCOLM, C. D. (2020) [37] | The development of the Smart Tourist Destination is interconnected, co-created and value-oriented through the implementation of technological applications and TIC infrastructures such as Cloud Computing and Internet of Things (BOES, Kim; BUHALIS, Dimitrios; INVERSINI, Alessandro, 2015) [1]. Information and Communication Technologies (TICs) are the fundamental components of smart tourism destinations, improving user experiences, efficiency, and process automation for sustainability. Although it is not the only feature, the TIC platform is essential for successfully realizing the concept of smart cities. (KHAN, M. Sajid et al. 2017) [33]. In addition to urban strategies, TICs also enhance daily life and communication, fostering conservation and development. (GOMEZ-OLIVA, Andrea et al. 2019) [27]. |

| Governance | GOMEZ-OLIVA, A. et al. (2019) [27]; ALLAWI, A. H. (2022) [28]; SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2020) [29]; GONZÁLEZ-REVERTÉ, F. (2019) [32]; KHAN, M. S. et al. (2017) [33]; BUHALIS, D.; AMARANGGANA, A. (2014) [38]; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2021) [7]; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2023) [34]; GRETZEL, U. et al. (2015) [2]; BOES, K.; BUHALIS, D.; INVERSINI, A. (2015) [1]; FEMENIA-SERRA, F.; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. (2021) [36]; MADEIRA, C.; RODRIGUES, P.; GOMEZ-SUAREZ, M. (2025) [39]; CORNEJO ORTEGA, J. L.; MALCOLM, C.D. (2020) [37] | Governance subsystems encompass tourism services such as travel procedures, visas, and special requirements, encompassing extraordinary government permits when required. (KHAN, M. Sajid et al. 2017) [33]. Smart governance refers to transparency in governance systems, modernizing urban administration with open data and public engagement (BUHALIS, Dimitrios; AMARANGGANA, Aditya. 2014) [38]. Governance implies the participation and collaboration of multiple actors (public, private, residents, and tourists) in smart tourist destinations’ decision-making, planning and policies, supported by advanced technologies and political leadership (SANTOS-JÚNIOR, Adalberto et al. 2020) [29]. |

| Innovation | ROMÃO, J.; NIJKAMP, P. (2019) [40]; GOMEZ-OLIVA, A. et al. (2019) [27]; ALLAWI, A. H. (2022) [28]; SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2020) [29]; MENDES FILHO, L. et al. (2022) [30]; SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2017) [31]; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2021) [7]; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2023) [34]; BOES, K.; BUHALIS, D.; INVERSINI, A. (2015) [1]; FEMENIA-SERRA, F.; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. (2021) [36]; MADEIRA, C.; RODRIGUES, P.; GOMEZ-SUAREZ, M. (2023) [39] | Innovation is the implementation of new ventures related to tourism and other activities with the support of TICs (SANTOS-JÚNIOR, Adalberto et al. 2020) [29]. The Innovation dimension in Smart Tourist Destinations involves the adoption of technologies such as QR code and RFID, as well as projects to improve services and municipal innovations. To become a DTI, innovative objectives are crucial, boosting a tourism ecosystem and favoring the consolidation of the destination through advanced management (MENDES FILHO, Luiz et al. 2022) [30]. The innovation dimension promotes initiatives that aim to encourage innovation in tourism and entrepreneurship. On the negative side, the degree of compliance with standardized innovation management systems is low in companies and public administrations. Innovation is primarily fostered by public administrations in DTI territories (IVARS-BAIDAL, Josep A. et al. 2021) [7]. |

| Accessibility | GOMEZ-OLIVA, A. et al. (2019) [27]; ALLAWI, A. H. (2022) [28]; SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2020) [29]; MENDES FILHO, L. et al. (2022) [30]; SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2017) [31]; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2021) [7]; IVARS-BAIDAL, J.A. et al. (2023) [34] | A DTI aims to include people in society with the support of smart technologies and accessibility (SANTOS-JÚNIOR, Adalberto et al. 2020) [29]. Accessibility means making tourism so that anyone can enjoy it. It makes it so that everyone can use the same things, like the environment, services, goods, technologies, and products in the safest, most comfortable, and most independent way possible (MENDES FILHO, Luiz et al. 2022) [30]. Regarding accessibility, further efforts are needed to ensure that all tourist attractions, information, and infrastructure are accessible to all visitors, regardless of their age, condition, or potential disability (IVARS-BAIDAL, Josep A. et al. 2021) [7]. |

| Performance | GOMEZ-OLIVA, A. et al. (2019) [27]; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2021) [7]; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2023) [34]; BORGES et al. (2022); ROMÃO, J.; NIJKAMP, P. (2019) [40] | Smart destinations need a complete set of metrics encompassing performance in the various areas they are expected to engage. This includes connectivity, analysis of large volumes of data, adoption of technology, and its integration with sustainability concerns and accessibility of destinations (IVARS-BAIDAL, CELDR’AN-BERNABEU, Maz’on, & PERLES-IVARS, 2023) [34]. Technologies such as the Internet of Things, Big Data, and mobile devices will allow destinations to better understand the tourist behavior in this data intelligence environment, reducing uncertainties about consumption habits. DTI should focus on enhancing the tourist experience through technologies such as augmented and virtual reality (MENDES FILHO, Luiz et al. 2022) [30]. |

| Mobility/urban infrastructure | KHAN, M. S. et al. (2017); BUHALIS, D.; AMARANGGANA, A. (2014) [38]; BOES, K.; BUHALIS, D.; INVERSINI, A. (2015) [1]; MADEIRA, C.; RODRIGUES, P.; GOMEZ-SUAREZ, M. (2023) [39]; CORNEJO ORTEGA, J. L.; MALCOLM, C.D. (2020) [37] | The Mobility dimension involves services including air, land, and water transportation modes. Intelligent roads, bridges, and tunnels, Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSs), and intelligent traffic and parking management are integrated with tourism to provide tourists with seamless integration of travel-related services (KHAN, M. Sajid et al. 2017) [33]. Smart Mobility refers to accessibility in and out of the city and the availability of modern transportation systems (BUHALIS, Dimitrios; AMARANGGANA, Aditya. 2014) [38]. Smart accessibility and mobility mainly refer to transportation that facilitates local interconnections of the destination for tourists and potential tourists (ALLAWI, Ahmed Hussein. 2022) [28]. The mobility dimension is about the modernization of public transport, improving traffic through real-time information and other technologies, and creating alternative means of transport (SANTOS-JÚNIOR, Adalberto et al. 2020) [29]. |

| Sustainability | GOMEZ-OLIVA, A. et al. (2019) [27]; SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2020) [29]; ALLAWI, A. H. (2022) [28]; ROMÃO, J.; NIJKAMP, P. (2019) [40]; MENDES FILHO, L. et al. (2022) [30]; SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2017) [31]; GONZÁLEZ-REVERTÉ, F. (2019) [32]; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2021) [7]; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2023) [34]; FEMENIA-SERRA, F.; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2023) [41]; AGUIRRE, A. et al. (2022) [42]; CORNEJO ORTEGA, J. L.; MALCOLM, C.D. (2020) [37] | The ideal smart tourism should be based on sustainability, circular economy, quality of life, and social value. The sustainability axis has the most significant number of publications on the theme of DTI (MADEIRA, Clara; RODRIGUES, Paula; GOMEZ-SUAREZ, Monica. 2023) [39]. Destination sustainability indicators adopt the approach of balancing economic, social, and environmental sustainability (IVARS-BAIDAL, Josep A. et al. 2021) [7]. |

| Economic Sustainability | ROMÃO, J.; NIJKAMP, P. (2019) [40]; ALLAWI, A. H. (2022) [28]; SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2020) [29]; AGUIRRE, A. et al. (2022) [42]; KHAN, M. S. et al. (2017) [33]; BUHALIS, D.; AMARANGGANA, A. (2014) [38]; BOES, K. et al. (2015) [1]; BORGES-TIAGO, T.; VERÍSSIMO, J.; TIAGO, F. (2022) [35]; MADEIRA, C.; RODRIGUES, P.; GOMEZ-SUAREZ, M. (2023) [39] | The economic dimension includes local strengthening, jobs, standard of living, investments, and new businesses. This can increase tax revenues but also lead to higher costs of living and prices, as well as real estate speculation. The necessary balance between advantages and challenges (SANTOS-JÚNIOR, Adalberto et al. 2020) [29]. Economic dimension: where smart and innovative economic conditions and tools are provided to fuel entrepreneurship and competitiveness (KHAN, M. Sajid et al. 2017) [33]. Economic growth is directly connected to Information and Communication Technologies. Since the rise in computers, there has always been a constant recognition of the importance of technology in driving economic advancements (BOES, Kim; BUHALIS, Dimitrios; INVERSINI, Alessandro 2015). |

| Social Sustainability | ROMÃO, J.; NIJKAMP, P. (2019) [40]; GOMEZ-OLIVA, A. et al. (2019) [27]; SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2020) [29]; AGUIRRE, A. et al. (2022) [42]; KHAN, M. S. et al. (2017) [33]; BUHALIS, D.; AMARANGGANA, A. (2014) [38]; GRETZEL, U. et al. (2015) [2]; BOES, K.; BUHALIS, D.; INVERSINI, A. (2015) [1]; MADEIRA, C.; RODRIGUES, P.; GOMEZ-SUAREZ, M. (2023) [39] | Smart Tourism Destination initiatives (DTIs) contribute to the enhancement of local sustainability. It is critical that they not only improve visitor experiences to achieve this goal but also develop them through continuous dialog with locally staked parties, including local actors and residents. This approach ensures that the benefits arising from the tourism sector can be optimally distributed in local society (CORNEJO ORTEGA, José Luis; MALCOLM, Christopher D. 2020) [37]. The “People” dimension emphasizes a culture of learning, engagement, and innovation, with examples such as advanced education and intelligent security. This joins educational, innovation, and safety subsectors, all connected to local culture, providing tourists with access to cultural and social solutions. The “Life” dimension seeks to improve the quality of life through education, health, and culture, with a focus on smart buildings, eHealth, and advanced medical facilities. It connects the sustainable and smart tourism system to the quality of life, although many aspects mainly benefit local residents. The integration of health services with tourist buildings and facilities is the main link with tourism in this dimension (KHAN, M. Sajid et al. 2017) [33]. “Smart People” refers to the level of skills and knowledge of the city’s human capital. On the other hand, “Smart Living” covers the quality of life, including a healthy environment, social cohesion, tourist attractiveness, and the availability of cultural and educational services (BUHALIS, Dimitrios; AMARANGGANA, Aditya. 2014) [38]. |

| Environmental Sustainability | AGUIRRE, A. et al. (2022) [42]; KHAN, M. S. et al. (2017) [33]; BUHALIS, D.; AMARANGGANA, A. (2014) [38]; BOES, K.; BUHALIS, D.; INVERSINI, A. (2015) [1]; MADEIRA, C.; RODRIGUES, P.; GOMEZ-SUAREZ, M. (2023) [39] | In the “Environment” dimension, the focus is on intelligent asset management to reduce pollution and waste of resources. Examples include the integration of smart grids and buildings, advanced irrigation and water treatment systems, as well as intelligent rainwater and waste management. This dimension, together with its functionalities, integrates intelligent systems for the management of networks, buildings, water, sewage, and waste in the context of sustainable tourism. This creates an essential connection between tourism and sustainable practices at a macro level (KHAN, M. Sajid et al. 2017) [33]. Intelligent Environment is related to energy optimization that leads to sustainable management of available resources (BUHALIS, Dimitrios; AMARANGGANA, Aditya. 2014) [38]. |

| Dimension | Frequency in the Reviewed Literature | Author(s) | Geographical Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) | 13 | GOMEZ-OLIVA, A. et al. (2019) [27] | City—applied in Ceutí/Spain |

| ALLAWI, A. H. (2022) [28] | Regional/Provincial—applied in Karbala/Iraq | ||

| SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2020) [29] | City—analysis of residents’ quality of life in STDs | ||

| MENDES FILHO, L. et al. (2022) [30] | Cities—applied in Natal, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo/Brazil | ||

| SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2017) [31] | City—applied in Marbella, Málaga/Spain | ||

| GONZÁLEZ-REVERTÉ, F. (2019) [32] | City—analysis of Spanish STD plans | ||

| KHAN, M. S. et al. (2017) [33] | City—applied in Dubai | ||

| IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2021) [7] | City—evaluation of INVAT.TUR STD indicators | ||

| IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2023) [34] | City—based on Smart Cities | ||

| BOES, K.; BUHALIS, D.; INVERSINI, A. (2015) [1] | City—based on Smart Cities | ||

| BORGES-TIAGO, T.; VERÍSSIMO, J.; TIAGO, F. (2022) [35] | Bibliometric review | ||

| FEMENIA-SERRA, F.; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. (2021) [36] | City—applied in Benidorm/Spain | ||

| CORNEJO ORTEGA, J. L.; MALCOLM, C. D. (2020) [37] | City—applied in Puerto Vallarta/Mexico | ||

| Governance | 14 | GOMEZ-OLIVA, A. et al. (2019) [27] | City—applied in Ceutí/Spain |

| ALLAWI, A. H. (2022) [28] | Regional/Provincial—applied in Karbala/Iraq | ||

| SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2020) [29] | City—analysis of residents’ quality of life in STDs | ||

| GONZÁLEZ-REVERTÉ, F. (2019) [32] | City—analysis of Spanish STD plans | ||

| KHAN, M. S. et al. (2017) [33] | City—applied in Dubai | ||

| BUHALIS, D.; AMARANGGANA, A. (2014) [38] | City—based on Smart Cities | ||

| IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2021) [7] | City—evaluation of INVAT.TUR STD indicators | ||

| IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2023) [34] | City—based on Smart Cities | ||

| GRETZEL, U. et al. (2015) [2] | City—based on Smart Cities | ||

| BOES, K.; BUHALIS, D.; INVERSINI, A. (2015) [1] | City—based on Smart Cities | ||

| FEMENIA-SERRA, F.; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. (2021) [36] | City—applied in Benidorm/Spain | ||

| MADEIRA, C.; RODRIGUES, P.; GOMEZ-SUAREZ, M. (2023) [39] | City—bibliometric review | ||

| CORNEJO ORTEGA, J. L.; MALCOLM, C. D. (2020) [37] | City—applied in Puerto Vallarta/Mexico | ||

| Innovation | 11 | ROMÃO, J.; NIJKAMP, P. (2019) [40] | Regional—analysis of European regions |

| GOMEZ-OLIVA, A. et al. (2019) [27] | City—applied in Ceutí/Spain | ||

| ALLAWI, A. H. (2022) [28] | Regional/Provincial—applied in Karbala/Iraq | ||

| SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2020) [29] | City—analysis of residents’ quality of life in STDs | ||

| MENDES FILHO, L. et al. (2022) [30] | Cities—applied in Natal, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo/Brazil | ||

| SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2017) [31] | City—applied in Marbella, Málaga/Spain | ||

| IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2021) [7] | City—evaluation of INVAT.TUR STD indicators | ||

| IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2023) [34] | City—based on Smart Cities | ||

| BOES, K.; BUHALIS, D.; INVERSINI, A. (2015) [1] | City—based on Smart Cities | ||

| FEMENIA-SERRA, F.; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. (2021) [36] | City—applied in Benidorm/Spain | ||

| MADEIRA, C.; RODRIGUES, P.; GOMEZ-SUAREZ, M. (2023) [39] | City—bibliometric review | ||

| Accessibility | 7 | GOMEZ-OLIVA, A. et al. (2019) [27] | City—applied in Ceutí/Spain |

| ALLAWI, A. H. (2022) [28] | Regional/Provincial—applied in Karbala/Iraq | ||

| SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2020) [29] | City—analysis of residents’ quality of life in STDs | ||

| MENDES FILHO, L. et al. (2022) [30] | Cities—applied in Natal, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo/Brazil | ||

| SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2017) | City—applied in Marbella, Málaga/Spain | ||

| IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2021) [7] | City—evaluation of INVAT.TUR STD indicators | ||

| IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2023) [34] | City—based on Smart Cities | ||

| Performance | 5 | GOMEZ-OLIVA, A. et al. (2019) [27] | City—applied in Ceutí/Spain |

| IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2021) [7] | City—evaluation of INVAT.TUR STD indicators | ||

| IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2023) [34] | City—based on Smart Cities | ||

| BORGES-TIAGO, T.; VERÍSSIMO, J.; TIAGO, F. (2022) [35] | Bibliometric review | ||

| ROMÃO, J.; NIJKAMP, P. (2019) [40] | Regional—analysis of European regions | ||

| Mobility/Urban Infrastructure | 5 | KHAN, M. S. et al. (2017) [33] | City—applied in Dubai |

| BUHALIS, D.; AMARANGGANA, A. (2014) [38] | City—based on Smart Cities | ||

| BOES, K.; BUHALIS, D.; INVERSINI, A. (2015) [1] | City—based on Smart Cities | ||

| MADEIRA, C.; RODRIGUES, P.; GOMEZ-SUAREZ, M. (2023) [39] | City—bibliometric review | ||

| CORNEJO ORTEGA, J. L.; MALCOLM, C. D. (2020) [37] | City—applied in Puerto Vallarta/Mexico | ||

| Sustainability | 19 | GOMEZ-OLIVA, A. et al. (2019) [27] | City—applied in Ceutí/Spain |

| SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2020) [29] | City—analysis of residents’ quality of life in STDs | ||

| ALLAWI, A. H. (2022) [28] | Regional/Provincial—applied in Karbala/Iraq | ||

| ROMÃO, J.; NIJKAMP, P. (2019) [40] | Regional—analysis of European regions | ||

| MENDES FILHO, L. et al. (2022) [30] | Cities—applied in Natal, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo/Brazil | ||

| AGUIRRE, A. et al. (2022) [42] | City—applied in Benidorm/Spain | ||

| SANTOS-JÚNIOR, A. et al. (2017) [31] | City—applied in Marbella, Málaga/Spain | ||

| GONZÁLEZ-REVERTÉ, F. (2019) [32] | City—analysis of Spanish STD plans | ||

| IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2021) [7] | City—evaluation of INVAT.TUR STD indicators | ||

| IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. et al. (2023) [34] | City—based on Smart Cities | ||

| FEMENIA-SERRA, F.; IVARS-BAIDAL, J. A. (2023) [41] | City—applied in Benidorm/Spain | ||

| CORNEJO ORTEGA, J. L.; MALCOLM, C. D. (2020) [37] | City—applied in Benidorm/Spain | ||

| KHAN, M. S. et al. (2017) [33] | City—applied in Dubai | ||

| BUHALIS, D.; AMARANGGANA, A. (2014) [38] | City—based on Smart Cities | ||

| BORGES-TIAGO, T.; VERÍSSIMO, J.; TIAGO, F. (2022) [35] | Bibliometric review | ||

| MADEIRA, C.; RODRIGUES, P.; GOMEZ-SUAREZ, M. (2023) [39] | City—bibliometric review | ||

| GRETZEL, U. et al. (2015) [2] | City—based on Smart Cities | ||

| BOES, K.; BUHALIS, D.; INVERSINI, A. (2015) [1] | City—based on Smart Cities |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garcia, T.S.; Tricárico, L.T. Urban Dimensions and Indicators for Smart Tourist Destinations from a State of the Art. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9110471

Garcia TS, Tricárico LT. Urban Dimensions and Indicators for Smart Tourist Destinations from a State of the Art. Urban Science. 2025; 9(11):471. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9110471

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcia, Thaís Siqueira, and Luciano Torres Tricárico. 2025. "Urban Dimensions and Indicators for Smart Tourist Destinations from a State of the Art" Urban Science 9, no. 11: 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9110471

APA StyleGarcia, T. S., & Tricárico, L. T. (2025). Urban Dimensions and Indicators for Smart Tourist Destinations from a State of the Art. Urban Science, 9(11), 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9110471