Validation of the Interpretative Model of the READI® Matrix for Territorial Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Method

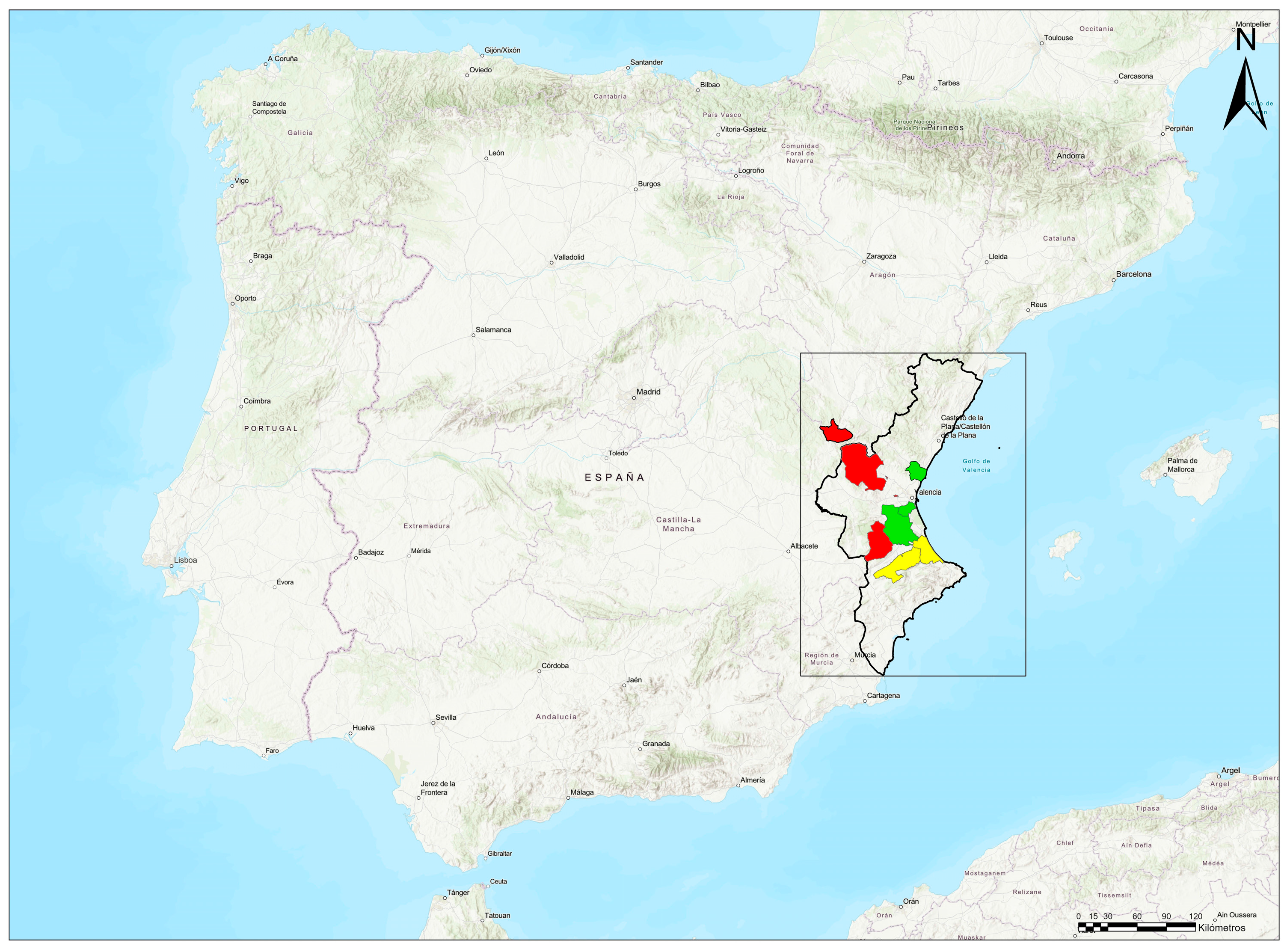

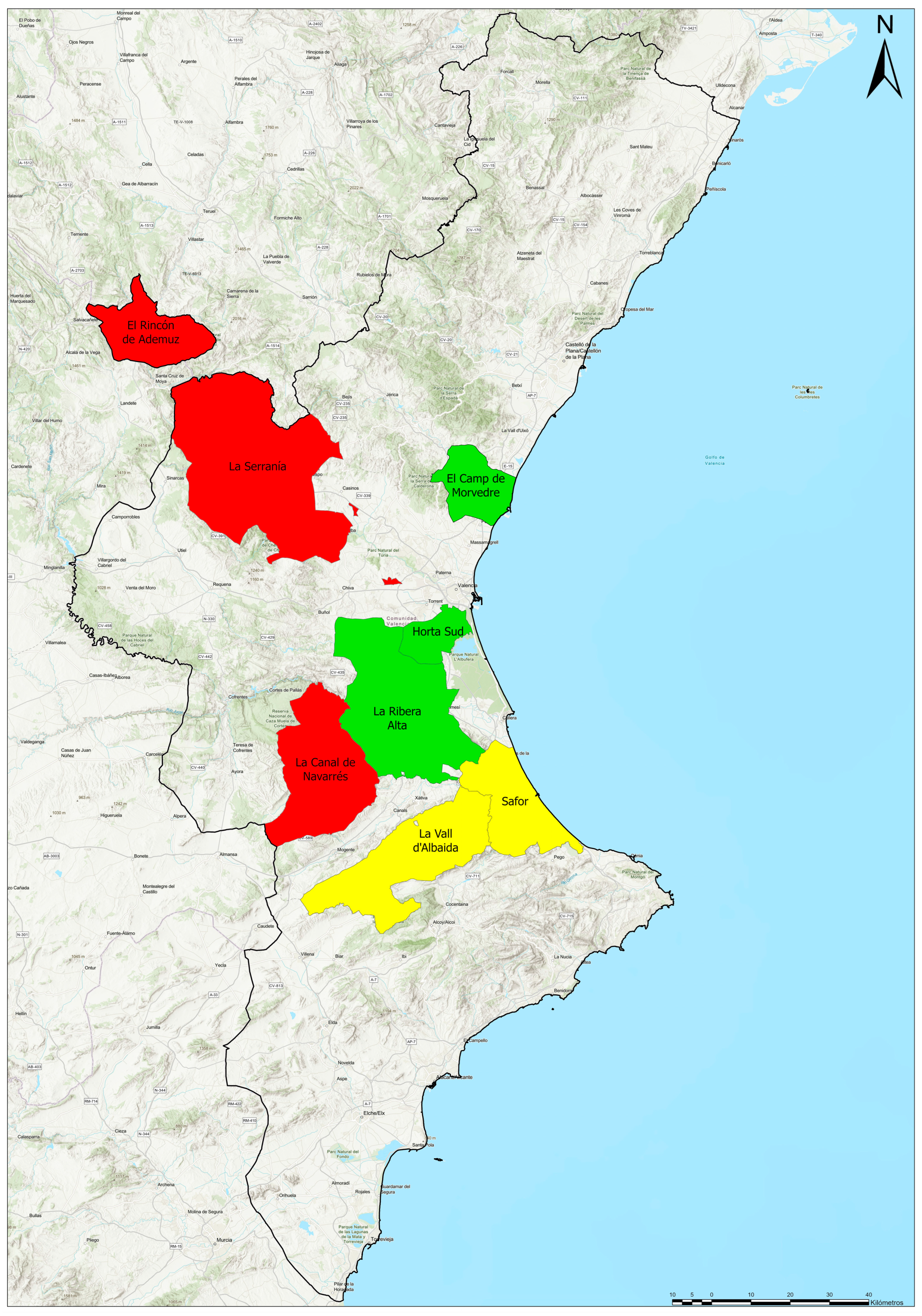

Territorial Sample

3. Results of the Methodological Discussion: The Proposed Interpretation of the Scenarios

- Scenario 1. Territories with a serious lack of competences to tackle local development processes. They are characterised by very low scores (clearly insufficient) and are also unbalanced between the three blocks of elements, with little possibility of strengthening them, most probably because they have not even detected the resources that could be available to them.

- Scenario 2. Territories with certain difficulties in harnessing their development competences. Scenarios that respond to partial imbalances to be considered, as they can make the subsequent implementation of development processes very difficult.

- Scenario 3. Territories with average (basic) competences to face local development processes, and in whose scenarios, in addition to having a certain level of competences, there is a certain balance between the groups of elements, which facilitates the proposal of actions to improve the territory’s reality. So, we would be talking about territories with a certain degree of stability in terms of competences, but which encounter difficulties at some point with the possession and use of resources for development or with the balance of these resources.

- Scenario 4. Territories with interesting competences (outstanding, existing in absolute terms) but in which the elements present a certain imbalance between them or between some of them, usually with a large number of resources, to the detriment of the rest of the elements (actors and dynamics), which tend to have lower scores.

- Scenario 5. Territories in which the competence-generating elements are not very abundant in absolute (total) terms, although they do provide a certain balance between them (coherence between resources, actors and dynamics), between the weight or presence that each of them has. This aspect greatly favours the implementation of development processes.

- Scenario 6. Balanced territories with high potential a priori to tackle local development processes, both in terms of the competences available to them in terms of available resources, actors present and dynamics implemented, as well as the balance between them, which are aspects that provide guarantees for the implementation of actions on the same.

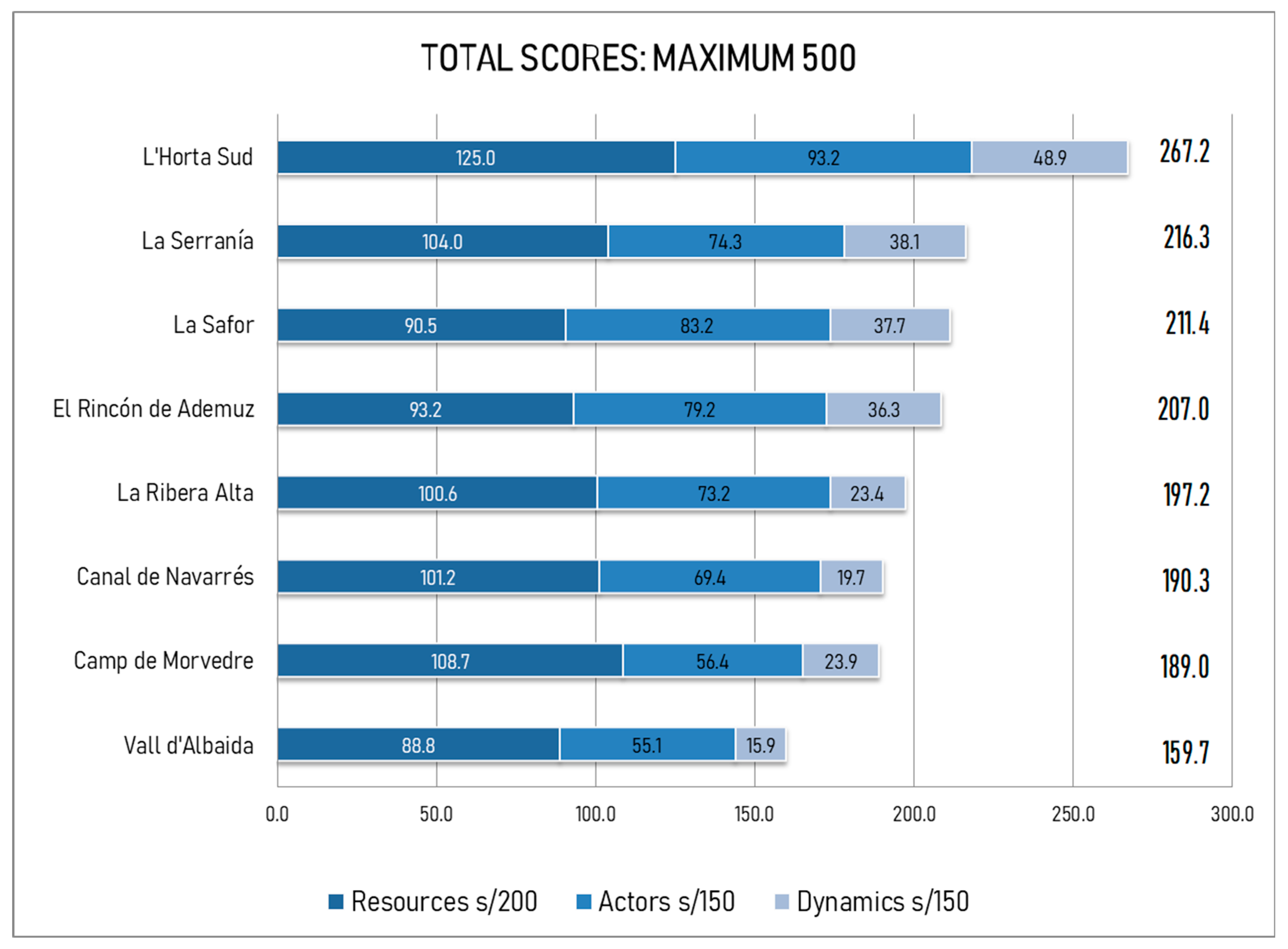

4. Results of Empirical Application of the Proposal to the Territories

5. Final Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramajo, J.; Márquez, M.A.; Hewings, G.J. Spatio-temporal analysis of regional systems. A multiregional spatial vector vutoregressive model for Spain. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2017, 40, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Puche, A. Perfil del personal técnico en gestión del desarrollo local en la Comunidad Valenciana. Un primer estudio exploratorio sobre funciones, necesidades y percepciones de su ejercicio profesional. TERRA Revista de Desarrollo Local 2021, 8, 361–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, C.; Domínguez-Mujica, J. Immigration and Local Endogenous Development in Rural Border Areas: A Comparative Study of Two Left-Behind Spanish Regions. Agriculture 2025, 15, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salom, J.; Albertos, J.M.; Pitarch, M.D.; Delios, E. Sistema Urbano e Innovación Industrial en el País Valenciano; Departamento de Geografía, Universitat de València: Valencia, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Alamá-Sabater, L.; Márquez, M.Á.; Tortosa-Ausina, E. Spatio-sectoral heterogeneity and population–employment dynamics: Some implications for territorial development. Reg. Stud. 2022, 59, 2088725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-García, T.; Liern, V.; Pérez-Gladish, B.; Rubiera-Morollón, F. Measuring the territorial effort in research, development, and innovation from a multiple criteria approach: Application to the Spanish regions case. Technol. Soc. 2022, 70, 101975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novell, N.; Sorribes, J. Nou Viatge pel País Valencià; Universitat d’Alacant, Universitat de València i Institució Alfons el Magnànim: Valencia, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchis, J.R.; Melián, A. Perfil profesional de los agentes de empleo y desarrollo local en España. Rev. Fom. Soc. 2010, 65, 295–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybarra, J.A.; Doménech, R. Politique industrielle et gouvernance: L’experience des clusters innovants en Espagne. Innovations 2014, 44, 105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Lobato, J.A.; Pérez, C. Toward a More Integrated Approach to Planning and Implementing Local Development Policies to Tackle Rural Depopulation in Empty Spain. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2025, 151, 04024056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Álvarez, J.; Casares-Gallego, M.A.; López-Bahut, E.; Santos Vázquez, M.D.L.Á.; Seoane Prado, H.; Rocamonde-Lourido, J. An Integrated Planning Methodology for a Just Climatic Transition in Rural Settlements. Buildings 2024, 14, 4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vérez, V.; Gil-Ruiz, P.; Montero-Seoane, A.; Cruz-Souza, F. Rural Depopulation in Spain from a Gender Perspective: Analysis and Strategies for Sustainability and Territorial Revitalization. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catala, B.; Savall, T.; Chaves-Ávila, R. Social Economy and Public Private Partnerships: Analysis, Drivers, and Prospects from the Local Level for Territorial Development. Nonprofit Policy Forum 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermosilla, J. Territorio y Empleo. Desarrollo Territorial y Mercado Laboral Valenciano; Universitat de València: Valencia, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Miedes-Ugarte, B.; Flores-Ruiz, D. Strategies for the Promotion of Regenerative Tourism: Hospitality Communities as Niches for Tourism Innovation. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado, J.; Calvo, R.; Sigalat, E. La necesidad de ser capaces de aprovechar las singularidades de cada territorio. In Sistemas Territoriales y Recursos Para la Sostenibilidad; Mora, J., Loures, L., Velarde, J.G., Eds.; Thomson Reuters Aranzadi: Cizur Menor, Spain, 2022; pp. 489–499. [Google Scholar]

- Aguado, J.; Calvo, R.; Sigalat, E. El ámbito de desarrollo local Valenciano, ¿Un modelo dualizado? Una primera aproximación empírica. Rev. Estud. Reg. 2023, 127, 75–105. Available online: http://www.revistaestudiosregionales.com/documentos/articulos/pdf-articulo-2651.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Aguado, J.; Sigalat, E.; Calvo, R. Zonas funcionales y Desarrollo Territorial: Perfil diferenciado del personal técnico en desarrollo local de la Comunitat Valenciana (España). TERRA Revista Desarrollo Local 2024, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, R.; Sigalat, E.; Portet, J.J. La importancia de lo local en situaciones de crisis. El estudio de la provincia de Valencia 2007–2015. Prism. Soc. 2017, 19, 236–266. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, R.; Sigalat, E.; Aguado, J.A. La descoordinación territorial del desarrollo local: ¿demasiados actores para un mismo territorio? Una aproximación empírica a la realidad de la Comunitat Valenciana. OBETS. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2020, 15, 71–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigalat Signes, E.; Aguado Hernández, J.A.; Calvo Palomares, R. Sociología y desarrollo territorial: La formación en métodos y técnicas de investigación social de las candidaturas a agente de empleo y desarrollo local. Rev. Española Sociol. 2023, 32, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigalat Signes, E.; Aguado Hernàndez, J.A.; Grau Muñoz, A.; Calvo Palomares, R. Construyendo un nuevo marco de relación ciudadana en el territorio. In Gobernanza, Comunidades Sostenibles y Espacios Portuarios; Españoles, A.d.G., Ed.; Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles: Madrid, Spain, 2023; pp. 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigalat Signes, E.; Aguado Hernández, J.A.; Calvo Palomares, R. Políticas de participación como método de intervención en el territorio. In Tratado General de Trabajo Servicios Sociales y Política Social; Garcés-Bravo, J.E., de Mayorga Arias, R.D., Eds.; Tirant lo Blanch: Valencia, Spain, 2024; Volume 3, pp. 1807–1837. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo-Palomares, R.; Aguado-Hernández, J.A.; Sigalat-Signes, E.; Roig-Merino, B. A New Methodology to Assess Territorial Competence for Sustainable Local Development: The READI® (Resources-Actors-Dynamics) Matrix. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, R.; Sigalat, E.; Aguado, J.A. READI. Una Herramienta Para la Autoevaluación de los Territorios; Tirant lo Blanch: Valencia, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo-Palomares, R.; Aguado-Hernández, J.A.; Sigalat-Signes, E.; Roig-Merino, B. Evaluation of Territorial Capacity for Development: Population and Employment. Land 2023, 12, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantaloni, M.; Zucchini, M.; Zenobi, G.; Lodolini, E.M.; Marinelli, G.; Minelli, A.; Neri, D. Sustainable management strategy to preserve Green Infrastructure Heritage. The traditional landscape of olive trees in the city of Ancona, Italy. Land Use Policy 2025, 156, 107603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCDE. Iniciativas Locales Para la Creación de Empleo. Programa ILE; Ministerio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social: Canelones, Uruguay, 1984.

- Carta de Leipzig. Carta de Leipzig sobre Ciudades Europeas Sostenibles. In Proceedings of the Encuentro Informal de Ministros sobre Desarrollo Urbano y Cohesión Territorial, Leipzig, Germany, 24–25 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- CCE. Fortalecimiento de la Dimensión Local de la Estrategia Europea de Empleo. Comunicación de la Comisión al Consejo, al Parlamento Europeo, al Comité Económico y Social y al Comité de las Regiones; Comisión de las Comunidades Europeas: Brussels, Belgium, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- CE. Estrategia Territorial Europea. Hacia un Desarrollo Equilibrado y Sostenible del Territorio de la UE; Oficina de Publicaciones Oficiales de las Comunidades Europeas, Comisión Europea: Brussels, Belgium, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- CE. Agenda Territorial de la Unión Europea 2020, Hacia Una Europa Integradora, Inteligente y Sostenible de Regiones Diversas. In Proceedings of the Reunión Ministerial Informal de Ministros Responsables de Ordenación del Territorio y Desarrollo Territorial, Comisión Europea, Gödöllő, Hungary, 19 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ADLYPSE. El Reto del Desarrollo Local. Un Camino Desde la Proximidad al Ciudadano a la Necesaria Cooperación Interadministrativa Con Nuestra Generalitat; Federación de Personal Técnico en Gestión de Desarrollo Local de la Comunidad Valenciana: Quart de Poblet, Valencia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alburquerque, F. Perspectiva y Utilidad de la Práctica del Desarrollo Local Desde Un Enfoque Integrado; Universitat d’Alacant: Alicante, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chemezova, E.Y. Statistical methods in the solution of the applied problems of the development of territory. In Economic and Social Development: Book of Proceedings; Varazdin Development and Entrepreneurship Agency: Varaždin, Croatia, 2013; p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Glinskiy, V.; Serga, L.; Khvan, M. Assessment of environmental parameters impact on the level of sustainable development of territories. Procedia cirP 2016, 40, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioppolo, G.; Saija, G.; Salomone, R. Developing a Territory Balanced Scorecard approach to manage projects for local development: Two case studies. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.D.C.P.; Lutsak-Yaroslava, N.V. La producción científica sobre la innovación social para el desarrollo local. Una revisión bibliométrica. Prism. Soc. 2017, 19, 146–182. [Google Scholar]

- Raszkowski, A.; Bartniczak, B. Towards sustainable regional development: Economy, society, environment, good governance based on the example of Polish regions. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2018, 17, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Elomina, J.; Živojinović, I.; Lidestav, G.; Sandström, P.; Sandström, S.; Pülzl, H. Local stakeholder’s perspectives on development of economic activities: The Gällivare case. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2025, 23, 101664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfendtner-Heise, J.; Ackerschott, A.; Schwenck, C.; Lang, D.J.; Von Wehrden, H. Making mutual learning tangible: Mixed-method delphi as a tool for measuring the convergence of participants’ reciprocal understanding in transdisciplinary processes. Futures 2024, 159, 103365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenck, C.; Pfendtner-Heise, J.; von Wehrden, H. Unveiling local knowledge: A case study on inner development and sustainable transformation in rural areas. Discov Sustain. 2025, 6, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordvinov, O.; Kravchenko, T.; Vahonova, O.; Bolduiev, M.; Romaniuk, N.; Akimov, O.O. Innovative tools for public management of the development of territorial communities. Ad Alta J. Interdiscip. Res. 2021, 11, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J.A.F.; Ferreira, J.J.M. Methodologies for improving technology decision making for sustainable socio-economic development. Technol. Soc. 2023, 72, 102172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, G.; Mungaray, A. Los índices de competitividad en México. Gestión Política Pública 2017, 26, 167–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks-Bielska, R.; Wojarska, M.; Lizińska, W.; Babuchowska, K. Local Economic Development in the Context of the Institutional Efficiency of Local Governments. Eng. Econ. 2020, 31, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, C.; Poulain, S.; Ezvan, C. Le territoire et ses ressources, un commun comme un autre? HAL 2020, 2, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, S.M.; Fidélis, T.; Ramos, T.B. Measuring and comparing local sustainable development through common indicators: Constraints and achievements in practice. Cities 2014, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkova, E.G.; Shachovskaya, L.S.; Romanova, M.K. Bases of transition of the territory to sustainable development: Modern city. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 23, 1499–1507. [Google Scholar]

- Reznichenko, S.M.; Takhumova, O.V.; Zaitseva, N.A.; Larionova, A.A.; Dashkova, E.V.; Zotikova, O.N.; Filatov, V.V. Methodological aspects of assessing factors affecting the sustainable development of the region. Mod. J. Lang. Teach. Methods 2018, 8, 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, P.; Graziano, P.; Dallara, A. A capacity approach to territorial resilience: The case of European regions. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2018, 60, 285–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, L.; Puertas, R. Analysis of European competitiveness based on its innovative capacity and digitalization level. Technol. Soc. 2023, 72, 102206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, R.; Florea, R. Diagnostic Analysis-the Starting Point in the Elaboration of the Local Development Strategy Oriented Towards Regional Competitiveness. Econ. Transdiscipl. Cogn. 2019, 22, 202–207. [Google Scholar]

- Barile, S.; Quattrociocchi, B.; Calabrese, M.; Iandolo, F. Sustainability and the viable systems approach: Opportunities and issues for the governance of the territory. Sustainability 2018, 10, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matvieieva, Y.; Myroshnychenko, I.; Valenkevych, L. Optimization Model of the Socio-Ecological-Economic Development of the Administrative Territory. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2019, 10, 1874–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cárdenas, G.; Nieto, A. Towards rural sustainable development? Contributions of the EAFRD 2007–2013 in low demographic density territories: The case of Extremadura (SW Spain). Sustainability 2017, 9, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianmoena, L.; Rios, V. The Determinants of Resilience During the Great Recession in European Regions. Working Paper, Universidad Pública de Navarra. 2017. Available online: https://www.ec.unipi.it/documents/Ricerca/papers/2018-235.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ubago, Y.; Garcia-Lautre, I.; Iraizoz, B.; Pascual, P. Why are some Spanish regions more resilient than others? Pap. Reg. Sci. 2019, 98, 2211–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drebot, O.; Palianychko, N.; Vysochanska, M.; Sakharnatska, L.; Shpylova, Y. Assessment of sustainable development of rural areas. Agric. Resour. Econ. Int. Sci. E-J. 2025, 11, 120–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozdowski, G.; Dziekański, P.; Pawlik, A.; Kęsy, I. Empirical Analysis of the Impact of the Green Economy on the Spatial Diversity of Entrepreneurship at the Poviats Level in Poland: Preliminary Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanganelli, M.; Torrieri, F.; Gerundo, C.; Rossitti, M. An integrated strategic-performative planning methodology towards enhancing the sustainable decisional regeneration of fragile territories. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 53, 101920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, F.C.; Ferreira, F.A.; Govindan, K.; Ferreira, N.C.; Banaitis, A. Measuring urban digitalization using cognitive mapping and the best worst method (BWM). Technol. Soc. 2022, 71, 102131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Spina, L. Community Branding and Participatory Governance: A Glocal Strategy for Heritage Enhancement. Heritage 2025, 8, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshire, L.; Esparcia, J.; Shucksmith, M. Community resilience, social capital and territorial governance. Ager Rev. Estud. Sobre Despoblación Desarro. Rural. 2015, 18, 7–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparcia, J. Capital Social y Desarrollo Territorial: Redes Sociales y Liderazgos en las Nuevas Dinámicas Rurales en España. (Tesis Doctoral) Programa de Doctorado en Sociología. Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y de Sociología, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. 2017. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10803/457367 (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Vaňová, A.; Šúrová, J.; Seková, M. Human resources and competitiveness of the territory. Acta Acad. Karviniensia 2019, 19, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIReF. Plan de Acción de la Revisión del Gasto en Subvenciones del Conjunto de las Administraciones Públicas (Spending Review); Autoridad Independiente de Responsabilidad Fiscal: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Svetlana, S.; Dietmar, W.; Matveyko, R.; Teryukova, L. Management of territory development based on an integrated assessment. Eur. Sci. Rev. 2015, 11–12, 214–219. [Google Scholar]

- Tronina, I.A.; Tatenko, G.I.; Bakhtina, S.S. Matrix for Selecting Priorities for Innovative Development of the Territory Based on the Principles of “Smart Specialization” in the Digital Econom. Adv. Econ. Bus. Manag. Res. 2020, 138, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigalat Signes, E.; Calvo Palomares, R.; Aguado Hernández, J.A.; Payá Castiblanque, R. Validez de instrumento para medir la competencia territorial. Matriz READI para la autoevaluación de territorios competentes. Cuad. Geográficos 2021, 60, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindez, S. Metodologías Participativas Para Proyectos Socio Comunitarios; Universidad Nacional Experimental Simón Rodríguez: Maturín, Venezuela, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Parés, M. Repensar la Participación de la Ciudadanía en el Mundo Local; Diputació de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2017.

| MATRIX Summary—Resources, Actors and Dynamics | Scores |

|---|---|

| RESOURCES | |

| ECONOMIC | |

| Own funding sources | 15 |

| External funding sources (public) | 10 |

| External funding sources (public-private)) | 10 |

| External funding sources (private)) | 10 |

| Interest in and seeking participation in European projects | 5 |

| PRODUCTIVE | |

| Quantity of employment generated | 15 |

| Quality of employment generated | 20 |

| Productive fabric | 10 |

| Productive sectors (quantity) | 5 |

| Size of companies | 5 |

| HUMAN | |

| Average education level of the population | 10 |

| Labour migration balance (local employment system) | 10 |

| SPATIAL | |

| Natural resources | 10 |

| Tourism resources | 10 |

| Cultural resources | 10 |

| Production resources | 15 |

| Geographical location | 10 |

| Infrastructures | 10 |

| 200 | |

| ACTORS | |

| Specific resources for development | 25 |

| Presence of socioeconomic actors | 25 |

| Presence of variety of socioeconomic actors | 25 |

| Detection, study and analysis process | 20 |

| Contact process and collaboration proposals | 30 |

| Results obtained | 25 |

| 150 | |

| DYNAMICS | |

| Forums and meeting points | 30 |

| Types of forum and meeting points | 20 |

| Territorial leadership | 25 |

| Socio-institutional networks at local level | 25 |

| Methodologies and strategic plans | 25 |

| Joint vision of territorial development | 25 |

| 150 | |

| TOTAL MAXIMUM SCORE | 500 |

| County | Municipalities | Surface Area (Km2) | Population (2024) | Population Density (Res/km2) | Average Income per Unit of Consumption (€) | AEDL Sample | Semaphore |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Rincón de Ademuz | 7 | 370.22 | 2170 | 5.86 | 18,574 | 6 | |

| La Serranía | 19 | 1405.28 | 17,453 | 12.42 | 19,382 | 10 | |

| La Canal de Navarrés | 8 | 709.29 | 15,755 | 22.21 | 19,207 | 6 | |

| La Vall d’Albaida | 34 | 722.22 | 88,848 | 123.02 | 19,531 | 13 | |

| La Ribera Alta | 35 | 970.04 | 232,520 | 239.70 | 19,746 | 7 | |

| El Camp de Morvedre | 16 | 271.20 | 99,848 | 368.17 | 20,041 | 9 | |

| La Safor | 31 | 429.80 | 181,068 | 425.94 | 17,471 | 6 | |

| L’Horta Sud | 20 | 309.08 | 492,143 | 1592.28 | 19,000 | 7 | |

| Province of Valencia (Spain) | 266 | 10,806.09 | 2,709,433 | 250.73 | 19,772 | ||

| Total representation (%) | 63.91 | 48.00 | 41.70 |

| Dimension 1. Total Points Obtained | Dimension 2. Balance Between the 3 Elements/Blocks |

|---|---|

| Low (<150 points) | Low balance |

| Medium-low (151 to 200 points) | Medium-low balance |

| Medium (201 to 250 points) | Medium balance |

| Medium-high (251 to 300 points) | Medium-high balance |

| High (>301 points) | High balance |

| Balance Between the 3 Elements/Blocks (Resources, Actors and Dynamics) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium-Low | Medium | Medium-High | High | ||

| Total points obtained (resource + actors + dynamics) | Low (<150) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Medium-low (151 to 200 points) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | |

| Medium (201 to 250) | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | |

| Medium-high (251 to 300 points) | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | |

| High (>301) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | |

| Dimension 3. Disaggregated Level by Points of Each Element/Block (Resources, Actors and Dynamics) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Values | Competence Level | |

| >121 >91 >41 dynamics | resources actors | |

| >101–120 >71–90 >31–40 dynamics | resources actors | Territory with limited competences for development, with certain difficulties for development, |

| Territory that does not make full use of its competences (either of its resources, actors or dynamics) | ||

| >91–100 >61–70 >21–30 dynamics | resources actors | Territory in partial imbalance (of resources, actors or dynamics) |

| <90 <60 <20 dynamics | resources actors | Territory with low levels of competence |

| Balance Between the 3 Elements/Blocks | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium-Low | Medium | Medium-High | High | ||

| Total points obtained | Low < 150 | |||||

| Medium-low (151 to 200) | Vall d’Albaida Camp de Morvedre Canal de Navarrés La Ribera Alta | |||||

| Medium (201 to 250) | El Rincón de Ademuz La Safor La Serranía | |||||

| Medium-high (251 to 300) | L’Horta Sud | |||||

| High > 301 | ||||||

| Vall d’Albaida | Territory with low levels of competence for development in all three factors |

| Camp de Morvedre | Territory with low levels of competence for development in terms of actors, with limited competencies and certain difficulties in terms of dynamics, and which does not make full use of its competencies in resources. |

| Canal de Navarrés | Territory with low levels of competence for development in terms of dynamics, with limited competencies and certain difficulties in terms of actors, and which does not make full use of its competencies in resources. |

| El Rincón de Ademuz | Territory with limited competencies and certain difficulties for development in terms of resources and which does not make full use of its competencies in terms of actors and dynamics. |

| La Safor | Territory with limited competencies and certain difficulties for development in terms of resources and which does not make full use of its competencies in terms of actors and dynamics. |

| La Ribera Alta | Territory with limited competencies and certain difficulties for development in terms of dynamics and which does not make full use of its competencies in terms of resources and actors. |

| La Serranía | Territory that does not make full use of its competences in terms of resources, actors and dynamics. |

| L’Horta Sud | Territories with high competences (potentials) for development. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Palomares, R.C.; Hernández, J.A.A.; Signes, E.S. Validation of the Interpretative Model of the READI® Matrix for Territorial Development. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9110461

Palomares RC, Hernández JAA, Signes ES. Validation of the Interpretative Model of the READI® Matrix for Territorial Development. Urban Science. 2025; 9(11):461. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9110461

Chicago/Turabian StylePalomares, Ricard Calvo, Juli Antoni Aguado Hernández, and Enric Sigalat Signes. 2025. "Validation of the Interpretative Model of the READI® Matrix for Territorial Development" Urban Science 9, no. 11: 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9110461

APA StylePalomares, R. C., Hernández, J. A. A., & Signes, E. S. (2025). Validation of the Interpretative Model of the READI® Matrix for Territorial Development. Urban Science, 9(11), 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9110461