Extension of the Electricity Power Grid in Greater Accra and Grand Lomé: From the Perceived to the Resident’s Sense of Just/Unjust?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. From Spatial Justice to Accessibility and Co-Design

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.3. Methodological Approach

2.3.1. A Cross-Reading of Greater Accra and Grand Lomé

2.3.2. Data Collection and Analysis Techniques

- Observation using photography

- Individual Interview

- From sampling to administering the questionnaire

- Mapping

3. Results

3.1. Perceptions of the Expansion of the Electricity Network in Greater Accra and Grand Lomé

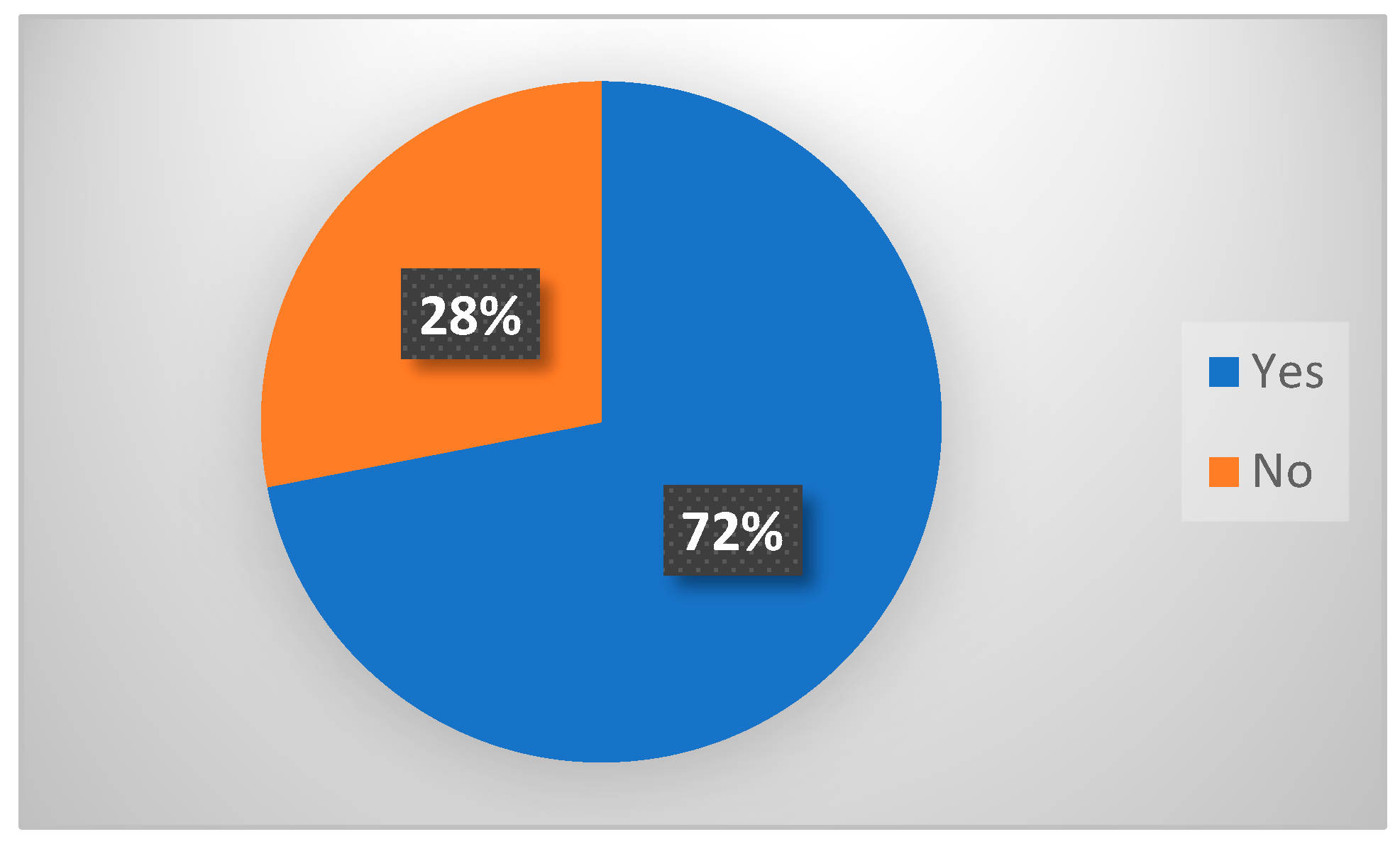

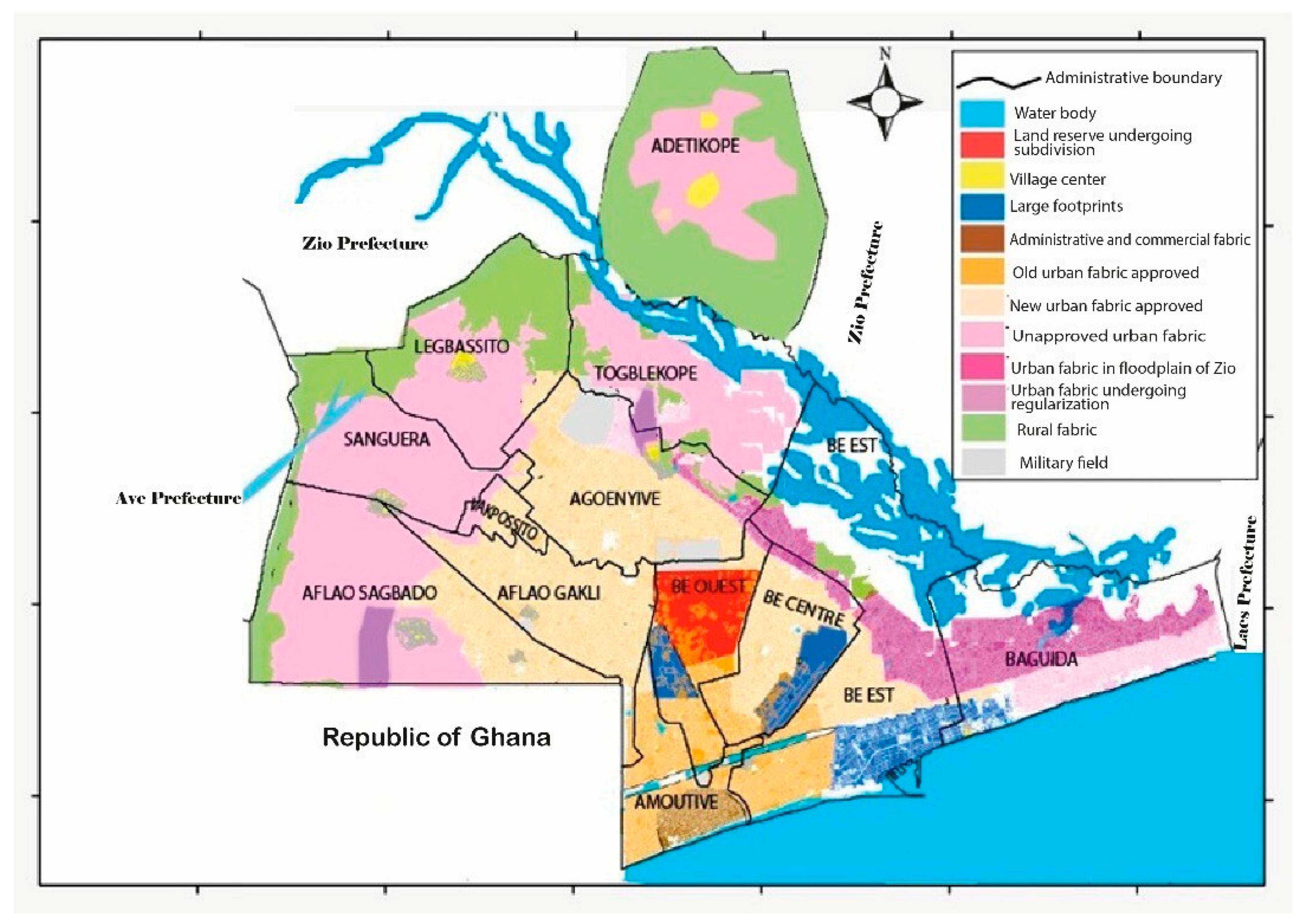

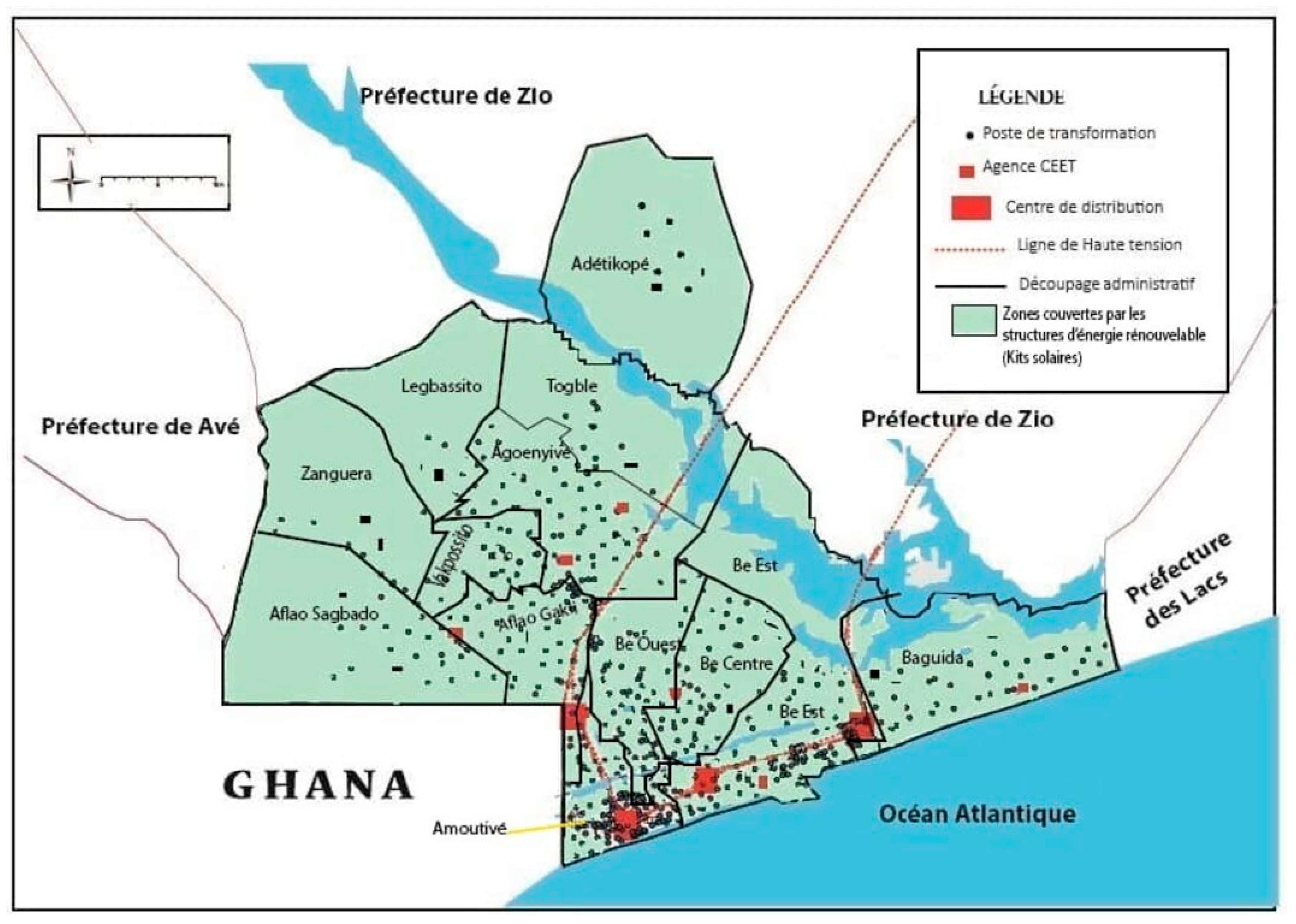

3.1.1. The Expansion of the Electricity Network as Perceived by the People of Lomé

“It’s not enough to pay the CEET estimate. You must know someone there. You must have contact. Many of us have paid the estimate, but so far, the CEET has not come to install the poles. And yet, we have paid, and it will soon be nine months.”.(Excerpt from an interview conducted on 25 June in Légbassito with Mr. F)

“There are always projects here at the CEET. But I can tell you that it’s political. For example, there is a project for the outlying districts of Lomé, but it has now been moved to Dapaong. Yes, there are projects, but the choice of locations for these lines is made on a flexible basis, with changes every day. This is the case for the extension lines currently proposed in the PRISET project…”.(Excerpt from the interview conducted on 12 March 2019, with Mr. D. at CEET)

3.1.2. The Deployment of the Electricity Network as Perceived by Accra Residents

“The NES master plan identified and prioritized 69 network-based electrification project packages to be implemented in six five-year phases. Connecting the district capitals (64 in total) and completing projects already underway were given top priority and were therefore included in the first phase of the master plan. The subsequent phases were prioritized based on economic criteria as well as political, traditional, and historical factors.”.(Excerpt from an interview conducted with Mr. G. in Adenta on 12 April 2021)

3.2. The Causes of Differing Perceptions in Greater Accra and Grand Lomé

3.2.1. Challenges to Collaboration Among Stakeholders Involved in Expanding the Electricity Grid

“There is no real relationship between the populations of the unconnected neighbourhoods of Lomé and CEET. They are not CEET subscribers… They are simply told that a project is coming, and they will have electricity… Internally, we work with the CVDs, giving priority to schools, public places, and the chief’s house. But in Lomé, this is not done”.(excerpt from the interview conducted on 12 March 2019, with Mr. D. at CEET)

“There is a collaborative relationship between CEET, CEB, and AT2ER. Since this agency does not have any equipment, it always comes to us. Our cartographic data is more up to date than that of the City Council and others. When I was working in cartography, a lady from the French Embassy used to come by all the time. We had data that even the road authorities didn’t have”.(excerpt from the interview conducted on 12 March 2019, with Mr. D. at CEET)

3.2.2. Challenging the Procedure for Implementing the Electricity Network Expansion Project

4. Discussion

4.1. Residents’ Feeling of Not Being Recognized by the Designer

“There is no official electricity network here. We don’t even have a road to get to the neighbourhood, and when it rains, the shortcuts that serve as paths are inaccessible because they are flooded with water from the gutters that flow into the neighbourhood. When this road was built, the government told contractors that no one should live there and that it could ensure that the water was drained towards the Zio. If you stand up there and look down, you will see that the entire road is covered in water. Those who are still behind us are suffering greatly.”.(Excerpt from an interview conducted on 27 July 2020, with Mr. J. in Koklovikopé)

“…an agricultural development zone/green and landscaped development zone. Construction for residential, commercial, industrial, recreational, and tourism purposes is prohibited… Only buildings for agricultural and market gardening use are permitted, as well as special areas dedicated to logistics. No social or community facilities may be built, except for sports and leisure facilities and urban parks.”[26]

“My brother, stop that. The government has certainly not yet approved Légbassito. But the same government has made Légbassito a municipality. We have a town hall, and the town hall officials go out into the field to collect taxes. So, they know that we live in this part of town. So why hasn’t the network been expanded here? The power lines you see were put up by the residents themselves. The official extensions made by CEET itself can be counted on one hand”.(excerpt from the interview conducted on Thursday, 25 July 2020, with Mr. Th. in Légbassito)

4.2. Feeling of Rejection of the Expansion of the Electricity Grid

“The agents responsible for extending the network are experiencing difficulties in installing electricity poles due to the topography of the ground. They are in bed of the Zio River. It is difficult to install a pole unless an embankment is built, as was done at the level of truck traffic and agricultural production towards Zogbédji. With all this, it is not possible to carry out an expansion project in this area”.(excerpt from the interview conducted on 12 March 2020, with Mr. D. at CEET)

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jaglin, S. Politiques d’infrastructures en Afrique subsaharienne: Le réseau est-il soluble dans la transition urbaine? In Du Béton au Numérique, le Nouveau Monde des Infrastructures; Éditions PIE Peter Lang SA: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2017; p. 177. [Google Scholar]

- Aholou, C.C.; Anoumou, K.R. La quête de l’eau à Légbassito, une revendication de l’appartenance au Grand Lomé. Notes Sci. 2017, 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kemausuor, F.; Obeng, G.Y.; Brew-Hammond, A.; Duker, A. A review of trends, policies and plans for increasing energy access in Ghana. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 5143–5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, A. John Rawls, Catherine Audard (Trad.), Théorie de la justice, Seuil, 1987. Homme Société 1988, 87, 122–123. [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann, T.; Saada, J. Théories de la reconnaissance dans les relations internationales. Cult. Confl. 2012, 87, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renault, E. L’expérience de L’injustice: Essai Sur la Théorie de la Reconnaissance; La Découverte: Paris, France, 2017; ISBN 978-2-7071-9461-9. [Google Scholar]

- Marcuse, P.; Connolly, J.; Novy, J.; Olivo, I.; Potter, C.; Steil, J. Searching for the Just City: Debates in Urban Theory and Practice; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Blondeau, C.; Sevin, J.-C. Entretien Avec Luc Boltanski, une Sociologie Toujours Mise à L’épreuve. Available online: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-01951913v1/document (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Cadiou, R. Aristote et La Notion De Justice. Rev. Études Grecques 1960, 73, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.; Alpe, Y.; Beitone, A. Lexique de sociologie. Lectures 2007, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castel, R. La dynamique des processus de marginalization: De la vulnérabilité à la désaffiliation. Cah. Rech. Sociol. 1994, 22, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnet, É. La théorie des « capabilités » d’Amartya Sen face au problème du relativisme. Tracés. Rev. Sci. Hum. 2007, 12, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévy, J.; Coldefy, J.; Piantoni, S.; François, J. Who Lives Where? 2023. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-04105977v1/file/Wholiveswhere.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Morange, M.; Quentin, A. Justice Spatiale, Pensée Critique et Normativité en Sciences Sociales. Available online: https://www.jssj.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/JSSJ12_MORANGEQUENTIN_VF.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Morange, M.; Calberac, Y. Géographies critiques » à la française »? Carnets Géograph. 2012, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moles, A.; Rohmer, E. Psychosociologie de L’espace; L'Harmattan: Paris, France, 1998; pp. 1–158. [Google Scholar]

- Reynaud, A. La géographie. Sci. Soc. 1982, 49, 1–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E.W.; Dufaux, F.; Gervais-Lambony, P.; Buire, C.; Henri, D. La justice spatiale et le droit à la ville: Un entretien avec Edward Soja. Justice Spatiale Spat. Justice 2011, 1–9. Available online: https://www.jssj.org/article/la-justice-spatiale-et-le-droit-a-la-ville-un-entretien-avec-edward-soja/ (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Marcuse, P. Spatial justice: Derivative but Causal of Social Justice. In Justice et Injustices Spatiales; Bret, B., Gervais-Lambony, P., Hancock, C., Landy, F., Eds.; Espace et Justice; Presses Universitaires de Paris Nanterre: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 76–92. ISBN 978-2-8218-2676-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hamant, Y. Après un Régime D’oppression: Entre Amnésie et Catharsis; Aires Linguistiques; Presses Universitaires de Paris Ouest: Paris, France, 2011; ISBN 978-2-84016-101-1. [Google Scholar]

- Löw, M.; Renault, D.; Bourdin, A. Sociologie de L’espace; Bibliothèque Allemande; Éditions de la Maison des Sciences de L’homme: Paris, France, 2015; ISBN 978-2-7351-2046-8. [Google Scholar]

- Brunet, R. De l’histoire naturelle à l’écologisme et retour. SPGEO 1992, 21, 219–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardayfio-Schandorf, E.; Yankson, P.W.K.; Bertrand, M. The Mobile City of Accra; African Books Collective: Oxford, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-2-86978-545-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kuévi, D. André Lomé, Capitale Politique et Économique de la Nécessité de Preserver son Patrimoine Culturel; Archives Nationales: Lomé, Togo, 1996; ISBN 2-906718-3. [Google Scholar]

- Marguerat, Y. La Naissance d’une Capitale Africaine: Lomé. Outre 1994, 81, 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agetur-Togo. Schéma Directeur D’aménagement et Urbanisation (SDAU) du Grand Lomé; Agetur-Togo: Lomé, Togo, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Anoumou, K.R. Non-accès à l’eau et à l’électricité dans le canton de Légbasito (Grand Lomé). In Dynamiques Locales Dans les Afriques en Mutation; Editions Rebetosch: Cotonou, Benin, 2017; ISBN 978-99a919-73-13-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Statistical Service. Ghana Statistical Service 2010 Population and Housing Census: District Analytical Report; Sakao Press Limited: Accra, Ghana, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Marguerat, Y. Dynamique Urbaine, Jeunesse et Histoire au Togo: Articles et Documents, 1984–1993; Collection “Patrimoines”; Presses de l’Université du Bénin: Lomé, Togo, 1993; ISBN 978-2-909886-13-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kouzan, K. Le Togo à la recherche de son indépendance énergétique (1961–2010). Outre 2010, 97, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyarko Kumi, E. The Electricity Situation in Ghana: Challenges and Opportunities|Center for Global Development. Available online: https://www.cgdev.org/publication/electricity-situation-ghana-challenges-and-opportunities (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Quartey, P. Innovative ways of making aid effective in Ghana: Tied aid versus direct budgetary support. J. Int. Dev. 2005, 17, 1077–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARSE. Rapport D’activités 2017; ARSE: Lomé, Togo, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Anoumou, K.R.; Sondou, T. Photography in urban studies in Greater Lomé, an objectifying approach? J. Infras. Policy. Dev. 2024, 8, 7749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.H. Urbanisme le Guide du Citoyen; Nouveaux Horizons: Paris, France, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Energy National Electrification Scheme (NES). Master Plan Review (2011–2020); Ministry of Energy National Electrification Scheme (NES): Accra, Ghana, 2010; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Jaglin, S. Services en Réseaux et Villes Africaines: L’universalité par D’autres Voies? Available online: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-03937117/file/Jaglin-EG_411_0051.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Zélem, M.-C.; Beslay, C. Sociologie de L’énergie: Gouvernance et Pratiques Sociales; Alpha; CNRS Éditions: Paris, France, 2015; ISBN 978-2-271-13047-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, C.D. L’accès pérenne à l’électricité à Nairobi: Diversité d’expériences et tensions sur le réseau. In Sociologie de L’énergie: Gouvernance et Pratiques Sociales; Zélem, M.-C., Beslay, C., Eds.; CNRS Alpha; CNRS Éditions: Paris, France, 2015; pp. 73–81. ISBN 978-2-271-13047-1. [Google Scholar]

- Olivier de Sardan, J.-P.; Omer, A.A.; Aissa, D.; Issa, Y.; Moussa, H.; Oumarou, A.; Tidjani, A.M. Gouvernance Locale et Biens Publics au Niger; Document de Travail; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Ghana National Electricity Grid Code; Energy Commission: Accra, Ghana, 2009.

- ARSE Code Bénino-Togolais de l’Electricité. Available online: https://are.bj/download/loi1_code-benino-togolais-de-lelectricite-revise-2015/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Criqui, L. Les voies de l’extension des réseaux de services essentiels dans les quartiers irréguliers de Lima. Rev. Tiers-Monde 2015, 221, 163–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoumou, K.R. Justice Spatiale et Accès à L’électricité: Regard Croisé Entre Greater Accra et Grand Lomé. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Lomé, Lomé, Togo, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| City | Number of People |

|---|---|

| Greater Accra | 34 |

| Grand Lomé | 78 |

| City | Number of People |

|---|---|

| Greater Accra | 48 |

| Grand Lomé | 96 |

| Argument Motivating Political Perception | Respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| No responses | 33 | 34.4 |

| The Central Office is not working | 7 | 7.3 |

| It is a matter of knowledge | 48 | 50 |

| Lack of facilities | 8 | 8.3 |

| Total | 96 | 100 |

| Element of Comparison | Residents | CEET Technical Agent | CEET Decision-Maker |

|---|---|---|---|

| Choice of extension location on personal initiative | Customer request | Customer request | Customer request |

| Choice of network expansion location for a project | Policy | Management decision | Administrative Council decision |

| Connection conditions | Payment of connection | estimate Payment of connection | estimate Payment of connection estimate |

| Conditions for completing the extension | within the deadline Have knowledge | Sign the work order (WO) | Payment of the connection estimate |

| Justification | Expansion of the Electricity Grid, a Political Decision | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | NA | ||

| It was a need expressed by the community | 00 | 23 | 04 | 27 |

| It is provided for in the local development plan | 00 | 16 | 02 | 18 |

| The choice of beneficiary localities | 03 | 00 | 00 | 03 |

| Total | 03 | 39 | 06 | 48 |

| Elements | Greater Accra | Grand Lomé |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship between the electric company and the population | Occasional | Occasional |

| Relationship between the electric company and the traditional chief | Permanent | None |

| Relationship between the electric company and the land use planning agent | Permanent | None |

| Relationship with local authorities | Permanent | None |

| Relationship with stakeholders in the energy sector | Permanent | Permanent |

| Greater Accra | Grand Lomé | |

|---|---|---|

| Step |

|

|

| Elements | Greater Accra | Grand Lomé | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extension Individual | Extension Made by the Company | Extension Individual | Extension Made by the Company | |

| Project design | After connection request | After annual network assessment | After connection request | After prospecting |

| Financing | The customer | EC; Financial partners | The customer | Financial partners |

| Consultation with those affected | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | No |

| Information at the start of work | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Organization in collaboration with the municipality | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Participatory action | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anoumou, K.R. Extension of the Electricity Power Grid in Greater Accra and Grand Lomé: From the Perceived to the Resident’s Sense of Just/Unjust? Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9110450

Anoumou KR. Extension of the Electricity Power Grid in Greater Accra and Grand Lomé: From the Perceived to the Resident’s Sense of Just/Unjust? Urban Science. 2025; 9(11):450. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9110450

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnoumou, Kouassi Rodolphe. 2025. "Extension of the Electricity Power Grid in Greater Accra and Grand Lomé: From the Perceived to the Resident’s Sense of Just/Unjust?" Urban Science 9, no. 11: 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9110450

APA StyleAnoumou, K. R. (2025). Extension of the Electricity Power Grid in Greater Accra and Grand Lomé: From the Perceived to the Resident’s Sense of Just/Unjust? Urban Science, 9(11), 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9110450