The Relationships Between Land Use Characteristics, Neighbourhood Perceptions, Socio-Economic Factors and Travel Behaviour in Compact and Sprawled Neighbourhoods in Windhoek

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

The 15-Min City and Broader Theoretical Perspectives on Neighbourhood Mobility

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Questions

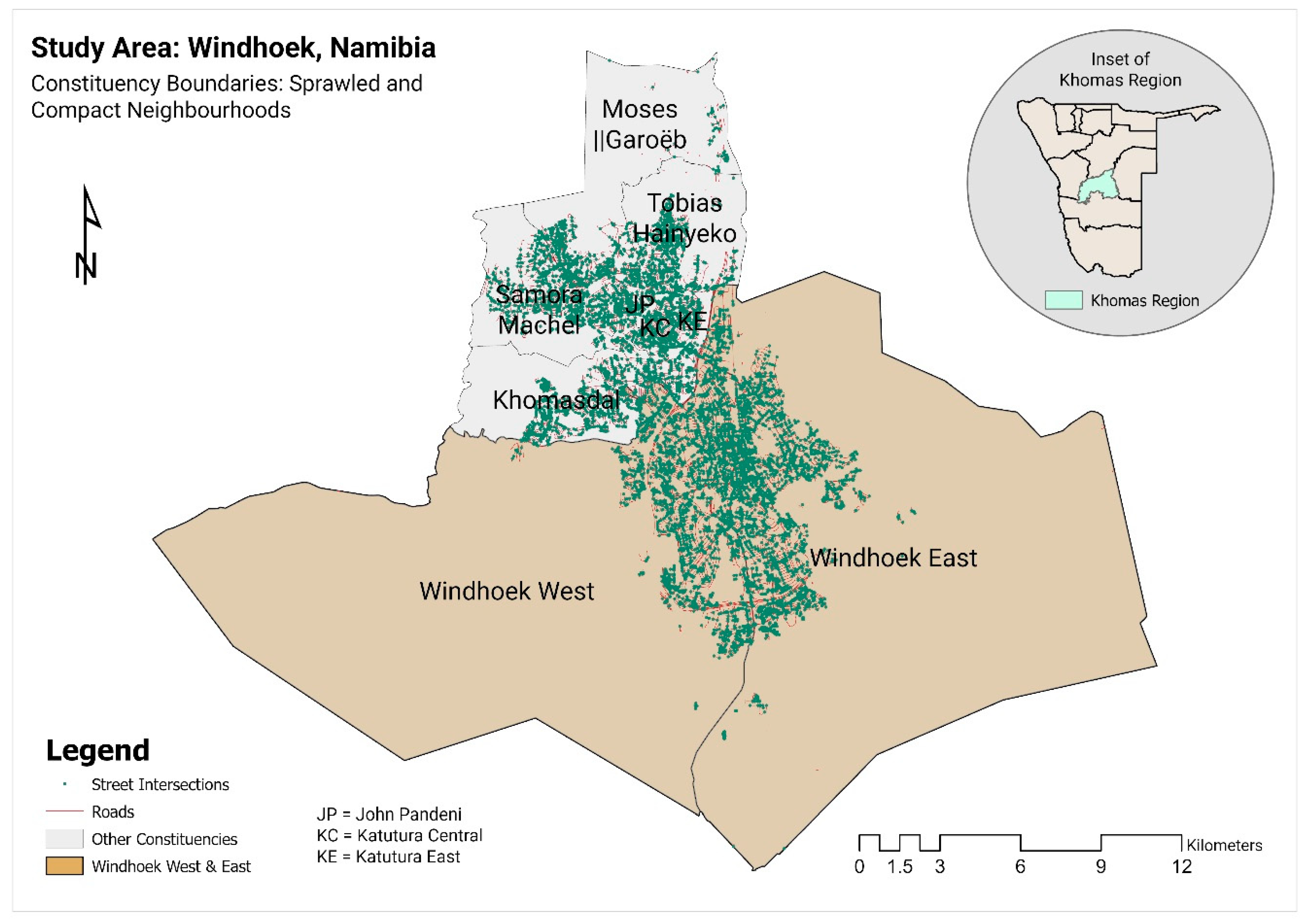

3.2. Case Study

3.3. Data and Variables

3.4. Analysis Methods

4. Results

4.1. Socioeconomic, Perceptual, and Mobility Differences Between Compact and Sprawled Neighbourhoods in Windhoek

4.2. Determinants of Neighbourhood-Based Shopping Travel in Compact and Sprawled Areas of Windhoek

4.3. Determinants of Neighbourhood-Based Entertainment and Recreational Travel in Windhoek

5. Discussion

5.1. Socio-Economic, Perceptual, and Behavioural Differences Between Compact and Sprawled Neighbourhoods in Windhoek

5.2. Neighbourhood Shopping Travel Behaviour in Windhoek: A Comparative Analysis of Compact and Sprawled Urban Forms

5.3. Urban Form, Perceptions, and Recreational Travel in Windhoek

5.4. The 15-Min City Framework as a Lens for Understanding Neighbourhood Mobility in Windhoek

6. Study Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mehriar, M.; Masoumi, H.; Aslam, A.B.; Gillani, S.M. The Neighborhood Effect on Keeping Non-Commuting Journeys within Compact and Sprawled Districts. Land 2021, 10, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convery, S.; Williams, B. Determinants of Transport Mode Choice for Non-Commuting Trips: The Roles of Transport, Land Use and Socio-Demographic Characteristics. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Cervero, R. Travel and the Built Environment. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2010, 76, 265–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, V.; Sinha, K. A Conceptual Framework for Promoting Neighborhood Social Sustainability: A Review of Literature. Future Cities Environ. 2025, 11, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroke, T.P. Successful Cities Are Based on Successful Neighbourhoods: A Strategic and Modelling Approach to Sustainable Integrated Neighbourhood Development. Ph.D. Dissertation, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa, 2016. Available online: https://repository.nwu.ac.za/items/4f19dd17-cd25-449d-9884-aaa3946f3626 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Dehghani, A.; Alidadi, M.; Sharifi, A. Compact Development Policy and Urban Resilience: A Critical Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iravani, H. Interconnected Street Networks Result in Mixed-Use: A Key to Alleviating Auto Traffic. J. Geotech. Transp. Eng. 2023, 8, 1. Available online: https://jgtte.com/issues/14/V7I2.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Dutta, S.; Bardhan, S.; Bhaduri, S.; Koduru, S. Understanding the Relationship between Density and Neighbourhood Environmental Quality-A Framework for Assessing Indian Cities. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2020, 15, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, C.; Mahendra, A.; Lionjanga, N. Urban Expansion and Mobility on the Periphery in the Global South. In Urban Form and Accessibility: Social, Economic, and Environment Impacts; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 243–264. ISBN 9780128198223. [Google Scholar]

- Kuma, C.; Gideon, S.; Kinyui, N. Rethinking Automobile Dependency in Sub-Saharan Africa: Toward Sustainable Urban Planning in Cameroon. Int. J. Transp. Eng. Technol. 2025, 11, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thondoo, M.; Marquet, O.; Márquez, S.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Small Cities, Big Needs: Urban Transport Planning in Cities of Developing Countries. J. Transp. Health 2020, 19, 100944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiran, G.A.B.; Ablo, A.D.; Asem, F.E.; Owusu, G. Urban Sprawl in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of the Literature in Selected Countries. Ghana. J. Geogr. 2020, 12, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.M.; Marchio, N. Infrastructure Deficits and Informal Settlements in Sub-Saharan Africa. Nature 2025, 645, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjipetekera, C.; Gumbo, T.; Yankson, E. Analysing the Causes and Challenges of Urban Spatial Expansion in Windhoek, Namibia: Towards Sustainable Urban Development Strategy. In Proceedings of the REAL CORP 2022—27th International Conference on Urban Development, Regional Planning and Information Society, Vienna, Austria, 14–16 November 2022; pp. 1–10, ISBN 978-3-9504945-1-8. [Google Scholar]

- Roland, S.; Stevens, Q.; Simon, K. The Uncanny Capital: Mapping the Historical Spatial Evolution of Windhoek. Urban Forum 2024, 35, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashilongo, M. Application of Rules of Transportation Planning Based on Principles of Transport Justice Developed by Karel Martens in Windhoek. Master’s Thesis, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 2020. Available online: https://open.uct.ac.za/items/155d92cc-fac5-49df-85a1-e9be57e05c42 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Kandjinga, L.; Landman, K. Planning for Safe Neighbourhoods in Namibia: A Comparative Case Study of Two Low-Income Neighbourhoods in the City of Windhoek. Dev. S. Afr. 2023, 40, 771–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamundu, E.; Vanderschuren, M.J. Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Urban Mobility (Non-Motorised Transport): A Case Study of Eveline Street in the Windhoek Municipality, Namibia. Master’s Dissertation, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 2020. Available online: https://open.uct.ac.za/bitstream/handle/11427/31484/thesis_ebe_2019_kamundu_erwin.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Sharifi, A.; Sadeghi, A. The 15-Minute City: Urban Planning and Design Efforts toward Creating Sustainable Neighborhoods. Cities 2023, 132, 104101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, S. Making US Cities Pedestrian- and Bicycle-Friendly. In Transportation, Land Use, and Environmental Planning; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 169–187. ISBN 9780128151679. [Google Scholar]

- Gutting, R.; Gerhold, M.; Rößler, S. Spatial Accessibility in Urban Regeneration Areas: A Population-weighted Method Assessing the Social Amenity Provision. Urban Plan. 2021, 6, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Hamidi, S. Compactness versus Sprawl: A Review of Recent Evidence from the United States. J. Plan. Lit. 2015, 30, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Cervero, R. “Does Compact Development Make People Drive Less?” The Answer Is Yes. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2017, 83, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldeeb, S.; Masoumi, H. Investigating Walkability and Bikeability in Compact vs. New Extensions: The Case of Greater Cairo. Front. Built Environ. 2023, 9, 1165996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elldér, E.; Haugen, K.; Vilhelmson, B. When Local Access Matters: A Detailed Analysis of Place, Neighbourhood Amenities and Travel Choice. Urban Stud. 2022, 59, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charreire, H.; Roda, C.; Feuillet, T.; Piombini, A.; Bardos, H.; Rutter, H.; Compernolle, S.; Mackenbach, J.D.; Lakerveld, J.; Oppert, J.M. Walking, Cycling, and Public Transport for Commuting and Non-Commuting Travels across 5 European Urban Regions: Modal Choice Correlates and Motivations. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 96, 103196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, L.A.; Peña, J.; Carrasco, J.A. Assessing the Role of the Built Environment and Sociodemographic Characteristics on Walking Travel Distances in Bogotá. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 88, 102844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehriar, M.; Masoumi, H.; Mohino, I. Urban Sprawl, Socioeconomic Features, and Travel Patterns in Middle East Countries: A Case Study in Iran. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, R.A. Spatial Structure, Intra-Urban Commuting Patterns and Travel Mode Choice: Analyses of Relationships in the Kumasi Metropolis, Ghana. Cities 2020, 96, 102432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welle, B. Paratransit in African Cities: Operations, Regulation, and Reform. Transp. Rev. 2019, 39, 556–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borker, G. Understanding the Constraints to Women’s Use of Urban Public Transport in Developing Countries. World Dev. 2024, 180, 106589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.; Bailey, A.; Lee, J. (Brian) Women’s Perceived Safety in Public Places and Public Transport: A Narrative Review of Contributing Factors and Measurement Methods. Cities 2025, 156, 105534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oostrum, M. Walkability and Colonialism: The Divergent Impact of Colonial Planning Practices on Spatial Segregation in East Africa. Cities 2024, 144, 104662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, J.; Sumich, J. Unseeing Urban Divides in Luanda and Maputo. Environ. Plan. D 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iamtrakul, P.; Chayphong, S.; Kantavat, P.; Nakamura, K.; Hayashi, Y.; Kijsirikul, B.; Iwahori, Y. Assessing Subjective and Objective Road Environment Perception in the Bangkok Metropolitan Region, Thailand: A Deep Learning Approach Utilizing Street Images. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoro, C.S.; Lawani, K. Optimising Sustainable Mobility: A Performance Assessment of Non-Motorised Transport Infrastructure in Johannesburg, South Africa. J. S. Afr. Inst. Civ. Eng. 2022, 64, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.C.; Porter, G.; Aouidet, H.; Dungey, C.; Han, S.; Houiji, R.; Jlassi, M.; Keskes, H.; Mansour, H.; Nasser, W.; et al. ‘No Place for a Woman’: Access, Exclusion, Insecurity and the Mobility Regime in Grand Tunis. Geoforum 2023, 142, 103753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massingue, S.A.; Oviedo, D. Walkability and the Right to the City: A Snapshot Critique of Pedestrian Space in Maputo, Mozambique. Res. Transp. Econ. 2021, 86, 101049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.; King, M.; Edwards, N.; Carroll, J.-A.; Watling, H.; Anam, M.; Bull, M.; Oviedo-Trespalacios, O. Downloaded from Search. Int. J. Crime. 2021, 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Olivari, B.; Cipriano, P.; Napolitano, M.; Giovannini, L. Are Italian Cities Already 15-Minute? Presenting the Next Proximity Index: A Novel and Scalable Way to Measure It, Based on Open Data. J. Urban Mobil. 2023, 4, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglione, F.; Gargiulo, C.; Zucaro, F.; Cottrill, C. Urban Accessibility in a 15-Minute City: A Measure in the City of Naples, Italy. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Procedia; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 60, pp. 378–385. [Google Scholar]

- Papas, T.; Basbas, S.; Campisi, T. Urban Mobility Evolution and the 15-Minute City Model: From Holistic to Bottom-up Approach. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Procedia; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1 January 2023; Volume 69, pp. 544–551. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, W.G. How Accessibility Shapes Land Use. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1959, 25, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurs, K.T.; van Wee, B. Accessibility Evaluation of Land-Use and Transport Strategies: Review and Research Directions. J. Transp. Geogr. 2004, 12, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurs, K.T.; De Montis, A.; Reggiani, A. Recent Advances and Applications in Accessibility Modelling. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2015, 49, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, D.S.; Ascensão, F.; Raposo, N.; Figueiredo, A.P. Comparing Access for All: Disability-Induced Accessibility Disparity in Lisbon. J. Geogr. Syst. 2017, 19, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Farber, S. Sizing up Transport Poverty: A National Scale Accounting of Low-Income Households Suffering from Inaccessibility in Canada, and What to Do about It. Transp. Policy 2019, 74, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friman, M.; Lättman, K.; Olsson, L.E. Public Transport Quality, Safety, and Perceived Accessibility. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vlugt, A.-L.; Gerten, C.; Scheiner, J. Integrating Perceptions, Physical Features and the Quality of the Walking Route into an Existing Accessibility Tool: The Perceived Environment Walking Index (PEWI). Act. Travel. Stud. 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeyns, I. The Capability Approach: A Theoretical Survey. J. Hum. Dev. 2005, 6, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizard, P.; Fukuda-Parr, S.; Elson, D. Introduction: The Capability Approach and Human Rights. J. Human. Dev. Capabil 2011, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, K. Transport and Social Exclusion: Where Are We Now? Transp. Policy 2012, 20, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.H.M.; Schwanen, T.; Banister, D. Distributive Justice and Equity in Transportation. Transp. Rev. 2017, 37, 170–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghestani, A.; Nikbakht, M.; Kucheva, Y.; Afshar, A. Assessing Spatial and Racial Equity of Subway Accessibility: Case Study of New York City. Cities 2024, 155, 105489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molvini, F. Accessibility to Public Transport: A Model with an Application to the City of Milan. Master’s Thesis, Politecnico di Milano, Milano, Italy, 2025. Advisor: Coppola, P.; Co-Advisor: Pastorelli, L. Available online: https://www.politesi.polimi.it/handle/10589/235025 (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Gera, K.; Hasdell, P. The Context and Experience of Mobility among Urban Marginalized Women in New Delhi, India. In Proceedings of the Synergy-DRS International Conference 2020, Online, 11–14 August 2020; Boess, S., Cheung, M., Cain, R., Eds.; Design Research Society: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, G.; Murphy, E.; Adamu, F.; Dayil, P.B.; Dungey, C.; Maskiti, B.; de Lannoy, A.; Clark, S.; Ahmad, H.; Yahaya, M.J. Young Women’s Travel Safety and the Journey to Work: Reflecting on Lived Experiences of Precarious Mobility in Three African Cities (and the Potential for Transformative Action). J. Transp. Geogr. 2025, 123, 104109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, M. Excavating Lefebvre: The Right to the City and Its Urban Politics of the Inhabitant. GeoJournal 2002, 58, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainstein, S.S. The Just City. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2014, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, F.; Sheller, M. Mobility Data Justice. Mobilities 2024, 19, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlinghieri, E.; Schwanen, T. Transport and Mobility Justice: Evolving Discussions. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 87, 102798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Palencia, I.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Gouveia, N.; Jáuregui, A.; Mascolli, M.A.; Slovic, A.D.; Rodríguez, D.A. Bicycle Use in Latin American Cities: Changes over Time by Socio-Economic Position. Front. Sustain. Cities 2023, 5, 1055351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nello-Deakin, S.; Harms, L. Assessing the Relationship between Neighbourhood Characteristics and Cycling: Findings from Amsterdam. Transp. Res. Procedia 2019, 41, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, H. Socio-Spatial Segregation in Residents’ Daily Life: A Longitudinal Study in Beijing. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 171, 103395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Yeh, A.G.O. Mobility-on-Demand Public Transport toward Spatial Justice: Shared Mobility or Mobility as a Service. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2023, 123, 103916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnene, O.A.; Mughogho, B.; Imuentinyan, A.; Nkurunziza, A.; Zuidgeest, M.H.P.; Martens, K.; Behrens, R. Transport Justice in Sub-Saharan Africa Challenges, Tools, Perspectives. In Transportation Research Procedia; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; Volume 89, pp. 584–593. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren, M.J.W.A.; Nnene, O.A. Inclusive Planning: African Policy Inventory and South African Mobility Case Study on the Exclusion of Persons with Disabilities. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2021, 19, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namibia Statistics Agency. Namibia 2023 Population and Housing Census Main Report; Namibia Statistics Agency: Windhoek, Namibia, 2024; Available online: https://nsa.org.na/census/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/2023-Population-and-Housing-Census-Main-Report-28-Oct-2024.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Mhangara, P.; Gidey, E.; Manjoo, R. Analysis of Urban Sprawl Dynamics Using Machine Learning, CA-Markov Chain, and the Shannon Entropy Model: A Case Study in Mbombela City, South Africa. Environ. Syst. Res. 2024, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarnia, N.; Harding, C.; Jaeger, J.A.G. How Suitable Is Entropy as a Measure of Urban Sprawl? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 184, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getu, K.; Bhat, H.G. Analysis of Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Urban Sprawl and Growth Pattern Using Geospatial Technologies and Landscape Metrics in Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehriar, M.; Masoumi, H.; Mohino, I. Street Connectivity and Active Mobility in Emerging Economies: Disparities of Socioeconomic Features and Travel Behavior in Sprawling versus Compact Urban Neighbourhoods. Int. Plan. Stud. 2024, 29, 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mboup, G.; Warah, R. Streets as Public Spaces and Drivers of Urban Prosperity; United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat): Nairobi, Kenya, 2013; ISBN 9789211325904. [Google Scholar]

- Mengistie, B.M.; Shi, W.Z.; Wong, M.S.; Zhu, R. Urban Street Network and Data Science Based Spatial Connectivity Evaluation of African Cities: Implications for Sustainable Urban Development. GeoJournal 2023, 88, 4753–4766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoglu, H. User’s Guide to Correlation Coefficients. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 18, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll Brandão, M.; França Sarcinelli, A.; Bisi Barcelos, A.; Postay Cordeiro, L. Leisure or Work? Shopping Behavior in Neighborhood Stores in a Pandemic Context. RAUSP Manag. J. 2023, 58, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Li, Y. Influence of the Perceptions of Amenities on Consumer Emotions in Urban Consumption Spaces. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderschuren, M.J.W.A.; Phayane, S.R.; Gwynne-Evans, A.J. Perceptions of Gender, Mobility, and Personal Safety: South Africa Moving Forward. Transp. Res. Rec. 2019, 2673, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatamzadeh, Y.; Habibian, M.; Khodaii, A. Walking Mode Choice across Genders for Purposes of Work and Shopping: A Case Study of an Iranian City. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2020, 14, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salon, D.; Gulyani, S. Commuting in Urban Kenya: Unpacking Travel Demand in Large and Small Kenyan Cities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antipova, A.; Sultana, S.; Hu, Y.; Rhudy, J.P. Accessibility and Transportation Equity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumi, H. Residential Location Choice in Istanbul, Tehran and Cairo: The Importance of Commuting to Work. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K.; Ettema, D.; Næss, P. Urban Form, Travel Behavior, and Travel Satisfaction. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 129, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) | Study Context | Main Findings | Relevance to the Present Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| [21] | USA (multiple cities) | Conceptual paper linking built environment and travel behaviour; emphasises that land use influences travel decisions through accessibility, safety, and perception. | Offers foundational theory connecting land use with neighbourhood travel behaviours. |

| [22] | Germany (Dresden) | Developed a population-weighted accessibility index using GIS to measure proximity to social amenities in urban regeneration areas. | Provides a methodological example of accessibility analysis in disadvantaged urban settings. |

| [23] | USA (scholarly response) | Responds to critiques suggesting compact development has a limited effect; argues strongly that D-variables do impact travel behaviour. | Reflects the importance of urban form in reducing car dependency, supporting this study’s core argument. |

| [24] | Meta-analysis of U.S. studies | Confirms that compact urban form significantly reduces vehicle miles travelled (VMT); supports the “5 D’s” (density, diversity, design, destination accessibility, distance to transit). | Empirical support for the claim that compact cities support sustainable travel. |

| [25] | Egypt (Greater Cairo Region) | Comparative study shows walkability is higher in historic core vs. new extensions; attributes it to compact urban form and integrated networks. | Illustrates differences between old and new urban forms in the Global South, supporting this study’s contextual relevance. |

| [26] | Sweden (Västra Götaland) | Finds that the presence and variety of local amenities influence walking and cycling; identifies nonlinear effects on travel mode choice. | Demonstrates the importance of amenity type and supply in promoting neighbourhood travel behaviour. |

| [27] | France, Belgium, Hungary, UK, Netherlands (multi-city) | Found that proximity to amenities is positively associated with physical activity and walking, but socioeconomic disparities affect access. | Highlights how built environment features interact with social equity, reflecting the importance of inclusive urban design. |

| [28] | Bogotá, Colombia | Identified that lower-income residents experience worse accessibility to opportunities, especially in peri-urban areas, due to spatial mismatch and limited transport. | Offers a Global South perspective on accessibility inequality, relevant for understanding access disparities in urban fringe areas. |

| [29] | Iran (Hamedan & Nowshahr) | Urban sprawl correlates with increased car use and reduces public transport, but patterns differ by city size and socioeconomic factors. | Provides empirical evidence of how sprawl affects travel behaviour differently in large vs. small Middle Eastern cities. |

| [30] | Ghana (Kumasi Metropolis) | Reveals that polycentric urban structure affects commuting patterns; suburban residents and higher-income earners are more likely to use private transport. | Demonstrates how spatial structure influences travel mode choice in African contexts, relevant for analysing socio-spatial disparities. |

| [31] | Sub-Saharan Africa (overview) | Reviews paratransit systems (e.g., matatus, tro-tros) as the dominant transport mode in African cities; highlights challenges of informality, lack of regulation, and reform needs. | Contextualises informal transport systems common in the Global South, important for planning inclusive mobility in rapidly urbanising areas. |

| [32] | Developing countries | Found that female commuters are willing to pay more to avoid harassment and safety concerns on public transport. Highlights the economic cost of unsafe transport environments. | Demonstrates the link between gendered safety concerns and travel decisions, critical for analysing equity in urban transport. |

| [36] | Thailand (Bangkok Metropolitan Region) | Used deep learning and semantic segmentation of street images to measure perceived vs. objective road environment; visual elements like nature, vehicles, and infrastructure shaped perception. | Innovative methodology combining AI and urban perception analysis; relevant for understanding the built environment’s subjective impacts. |

| [37] | South Africa (Johannesburg) | Evaluated non-motorised transport (NMT) infrastructure; found that despite good physical condition, usage was low due to safety and security concerns. | Highlights the gap between infrastructure provision and actual user uptake due to perceived insecurity, useful for urban design policy. |

| [38] | Tunisia (Grand Tunis) | Explores gendered mobility exclusion through women’s travel diaries; identifies how insecurity, poverty, and transport design marginalise women in mobility systems. | Critical perspective on intersectional transport exclusion, relevant for mobility justice and inclusive planning in the urban Global South. |

| [39] | Maputo, Mozambique | Found significant mobility challenges in peri-urban areas due to spatial inequalities, lack of infrastructure, and long commuting times, especially for women and low-income groups. | Provides crucial insights on transport exclusion in African cities, aligns with equity concerns in urban planning. |

| [40] | Bangladesh | Gender-based violence and safety concerns significantly restrict women’s mobility and mode choice. | Highlights how safety perceptions shape travel behaviour, supports the inclusion of safety and sense of belonging as key variables in the Windhoek travel behaviour study. |

| [41] | Italy (national scale) | Introduced the Next Proximity Index (NEXI), a scalable tool to measure 15-min accessibility using open data. Found variability in proximity within and between cities. | Presents a replicable method to evaluate spatial accessibility, with potential application in comparing international 15-min cities. |

| [42] | Naples, Italy | Evaluated urban morphology, street design, and service distribution in creating 15-min neighbourhoods. Found that geomorphology and socio-economic factors are key to walkability. | Offers a methodology to assess neighbourhood walkability and accessibility, supports spatial equity in 15-min city design. |

| [43] | Europe (multi-city review) | Emphasised the shift from top-down to bottom-up approaches in 15-min city planning, focusing on participatory urbanism and community engagement. | Supports a participatory model of mobility planning, relevant for integrating neighbourhood needs in urban accessibility strategies. |

| [44] | U.S., early empirical urban planning studies on land use | Introduced a model linking accessibility and land use; showed residential development correlates with accessibility to employment and other opportunities. | Provides foundational theory for understanding how accessibility shapes urban form; it forms the basis of many modern accessibility measurement approaches. |

| [45] | Dutch cities, multimodal accessibility measurement | Developed a framework for evaluating accessibility using land use, transport, temporal, and individual components. Emphasised the need for person-based measures and policy integration. | Supports multidimensional understanding of accessibility; aligns with the study’s focus on equity and inclusive mobility outcomes. |

| [47] | Lisbon, Portugal | Developed a method for quantifying “disability-induced accessibility disparity” using pedestrian network data. Found significant barriers in the built environment that reduce mobility for disabled persons. | Highlights accessibility inequities among disabled populations; supports the study’s inclusion of social vulnerability and universal design perspectives. |

| [48] | Canada (national-scale study across 8 metro areas) | Mapped transport poverty by analysing income levels and transit accessibility. Identified nearly 1 million Canadians in low-income households with poor transit access, mostly in low-density suburbs. | Offers empirical evidence on the intersection of accessibility and income inequality; it directly supports this study’s emphasis on spatial equity and transport justice. |

| [49] | 5 European cities (Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Finland | Found strong links between public transport use and subjective well-being, particularly through travel satisfaction. Emphasised the importance of perceived accessibility in enhancing the quality of life. | Supports broader evaluation of accessibility beyond physical availability, supporting inclusion of subjective and experiential dimensions in accessibility assessment. |

| [50] | Germany | Explored older adults’ access to public transport and found that lack of perceived safety and usability are key barriers. Emphasised the importance of age-sensitive and inclusive transport planning. | Reinforces the study’s attention to social vulnerability (elderly users) and the importance of equity-focused urban mobility design. |

| [51] | Theoretical work; global applicability | Provides a comprehensive survey of the capability approach, emphasising capabilities (substantive freedoms) over resources or utilities. Distinguishes between means and ends in evaluating well-being. | Offers theoretical grounding for capability-informed accessibility analysis, central to this study’s equity and justice framing. |

| [52] | Conceptual: Capability Approach and Human Rights | Explores synergy between human rights and the capability approach; advocates for policy frameworks that integrate dignity, freedom, and substantive equality as foundational values. | Bolsters the normative justification for capability-based approaches to accessibility and inclusion, particularly regarding rights-based urban policy frameworks. |

| [53] | United Kingdom | Reviews how transport disadvantage contributes to broader social exclusion. Highlights relational, multidimensional, and dynamic aspects of transport poverty and inequity. | Underpins key conceptual framework for this study; Lucas’ model of transport-related exclusion is foundational to policy framing on equitable access and transport justice. |

| [54] | Reviews of theories | Argued that accessibility must be reframed as a social equity issue, not merely a transport or land-use problem. Highlighted social exclusion risks in unequal urban accessibility. | Strengthens theoretical grounding for equity-driven accessibility analysis, aligning with the capability and justice approach in this study. |

| [55] | United States (New York City) | Found significant spatial and racial disparities in subway accessibility, particularly affecting Black communities in Queens. Used the gravity index and Gini coefficients for analysis. | Provides a methodologically robust example of racial and spatial equity analysis, useful for comparative metrics in urban transport justice. |

| [56] | Italy | Proposed a composite accessibility indicator integrating public transport, services, and walking access to assess social equity in urban settings. | Offers a comprehensive methodology for measuring multimodal accessibility in urban equity evaluations. |

| [57] | India (New Delhi) | Highlighted how informal transport enables spatial and social mobility for marginalised women facing cultural and safety barriers. | Informs the intersection of gender, informality, and accessibility in low-income urban settings—directly supporting this study’s justice lens. |

| [58] | Nigeria, South Africa, Tunisia | Revealed the gendered dimensions of urban transport exclusion through women’s experiences of harassment and scheduling constraints. Emphasised peer-led research. | Supports gender-sensitive accessibility approaches and inclusion of lived experiences in transport justice analysis. |

| [59] | Theoretical analysis | Critiqued the concept of “the right to the city” in neoliberal urbanism; highlighted risks of co-option and the need for participatory democratic control. | Informs critical framing of rights-based approaches in urban accessibility debates, especially under neoliberal planning regimes. |

| [60] | New York, London, Amsterdam | Proposed “the just city” framework combining equity, democracy, and diversity. Challenged utilitarian and market-based planning paradigms. | Establishes a strong normative basis for urban justice frameworks that intersect with transport equity. |

| [61] | Conceptual framework, Mobility Data Justice | Explored the social dynamics and contested nature of digital mobility platforms (e.g., MaaS), including issues of surveillance, access, and inequality. | Highlights how digital mobility innovations can both enable and restrict urban accessibility, important for equity analyses in future mobility. |

| [62] | Conceptual: Transport and mobility justice: | Reviewed developments in transport and mobility justice theory. Emphasised shift from state-centric to society-centric approaches and the need for inclusive epistemologies. | Frames the study’s justice lens, encouraging attention to grassroots knowledge, multiple actors, and community-led planning practices. |

| [63] | 18 Latin American cities | Found that bicycle use has increased across socio-economic groups, especially among the highly educated and high-income groups, although traditionally cycling was more common among lower-income populations. | Demonstrates how transport mode preferences evolve with infrastructure and cultural shifts; relevant for equity-focused active mobility policy. |

| [64] | Amsterdam, The Netherlands | Higher density, land-use mix, and street connectivity are linked to more cycling, with urban form remaining a strong predictor even after accounting for socio-demographic factors | Provides empirical evidence that supports the importance of compact, connected, and mixed-use urban design in shaping active travel choices. |

| [65] | Beijing, China | Analysed spatial mismatch between jobs and housing and how metro accessibility affects commuting burden; found access varies by income group. | Informs accessibility analyses by highlighting how transit systems unevenly serve socio-economic groups. |

| [66] | Chengdu, China | Compared shared mobility (SM) and Mobility as a Service (MaaS) in improving spatial justice; MaaS was found to be more equitable. | Offers empirical support for prioritising integrated multimodal approaches (MaaS) over fragmented services for urban equity. |

| [67] | Kigali (Rwanda), Blantyre (Malawi) | Proposed “transport justice” framework for Sub-Saharan Africa; highlighted severe inequality in car access and opportunity. | Grounds the study in Global South realities, reinforcing equity-based planning tailored to marginalised urban populations. |

| [68] | South Africa | Assessed disability inclusion in African transport policies; found systemic neglect leading to isolation of persons with disabilities. | Emphasises inclusive transport policy as foundational for equitable access, particularly for people with disabilities. |

| Constituency | Area in km2 | Persons per km2 | Socio-Economic Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| John Pandeni | 3.18 | 8010.7 | Historically disadvantaged, overcrowded, low-income housing |

| Katutura Central | 2.53 | 12,054.2 | Very high density, informal settlements, limited services |

| Katutura East | 4.36 | 5267.3 | Peripheral, predominantly low-income, weak amenity access |

| Khomasdal | 23.52 | 2857.7 | Mixed-income, fragmented infrastructure, limited retail integration |

| Moses//Garoeb | 32.37 | 2129.2 | High density, largely informal, poor service provision |

| Samora Machel | 20.30 | 4551.1 | Overcrowded, peripheral township, socio-economically marginalised |

| Tobias Hainyeko | 18.51 | 3623.8 | Lower-income, limited formal infrastructure, and fragmented land use |

| Windhoek East | 218.93 | 137.3 | Affluent, well-serviced, high land-use diversity and accessibility |

| Windhoek West | 208.08 | 287.9 | Middle- to high-income, planned housing, better service integration |

| Variable Name | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Socio-Economic Characteristics | ||

| Age | Dummy | Respondents selected an age category. The categorical variable was coded as a dummy. 0 = Under 35 years, 1 = 35 years and above |

| Gender | Categorical | Gender of respondent 0 = Female, 1 = Male |

| Education | Dummy | Respondents selected their highest level of education; the categorical variable was coded as a dummy variable. 0 = Lower Education (Primary & Secondary) 1 = Higher Education (College & University) |

| Car Ownership in a Household | Continuous | Number of cars owned in the respondent’s household. |

| Driving licence | Categorical | Whether the respondent has a driving licence. 0 = Yes, 1 = No |

| Number of driving licenses/households | Continuous | Number of people with licenses in the household |

| Household Size (Adults) | Continuous | Number of adults in the respondent’s household. |

| Household Size (Children) | Continuous | Number of children in the respondent’s household. |

| Income | Dummy | Respondents selected their household income category, and responses were coded as a dummy variable. 0 = <N$5000, 1 = >N$5000 |

| Land Use and Built Environment | ||

| Population Density | Continuous | The average number of people per square kilometre (extracted from the Namibian 2023 Population & Housing Census Report) |

| Length/street density around home | This variable was not self-reported but derived using Geographic Information Systems (GIS). It measures street connectivity by calculating the total length of roads within each zone, divided by the zone’s area. The computation was performed in ArcGIS Pro using road network data from OpenStreetMap (OSM) | |

| Intersection density around home | Continuous | Number of street intersections per km2 around the respondent’s home location; derived from GIS data. |

| Perceived access to employment opportunities | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| Perceived access to educational institutions | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| Perceived access to healthcare facilities | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| Perceived access to shopping and amenities | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| Perceived access to parks and recreational areas | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| Neighbourhood Perceptions | ||

| Sense of belonging to the neighbourhood | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| I avoid boredom by visiting new places | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| There are attractive shops or shopping centres in my neighbourhood | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| Attractiveness of social/recreational facilities in the neighbourhood | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| Preference for neighbourhood entertainment | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| A preference to have entertainment far from the neighbourhood | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| No suitable shops as a reason for not shopping in the neighbourhood | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| No good social atmosphere as a reason for not shopping in the neighbourhood | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| Shops are too expensive as a reason for not shopping in the neighbourhood | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| Little security in the neighbourhood | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| I avoid boredom by visiting new places as a reason for not shopping in the neighbourhood | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| Affordable house as a residential location choice | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| Near workplace/school as a residential location choice | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| Attractive surrounding environment as a residential location choice | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| Secure area as a residential location choice | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| I have lived here since birth/childhood as a residential location choice | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| Ease of commute to the workplace as a reason for choosing a neighbourhood | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| Traffic safety perception when walking in the neighbourhood | Continuous | Agreement with walking/cycling to nearby destinations -Agreement score (0–100) |

| The streets are not safe, as a reason for not walking in the neighbourhood | Continuous | Agreement score (0–100) |

| Ease of navigating the neighbourhood by car | Continuous | Ease of navigating neighbourhood by car (0–100 scale) -Agreement score (0–100) |

| Ease of navigating the neighbourhood on foot | Continuous | Ease of navigating neighbourhood on foot -Agreement score (0–100) |

| Ease of navigating the neighbourhood by bicycle | Continuous | Ease of navigating neighbourhood bicycle -Agreement score (0–100) |

| Proximity to e-hailing stops | Continuous | Perceived proximity to e-hailing stops (0–100 scale) |

| Travel Behaviour | ||

| Shopping Location (neighbourhood/far) | Categorical | Whether shopping is done in the neighbourhood or farther 0 = further, 1 = neighbourhood |

| E-hailing usage frequency | Continuous | How often a respondent uses e-hailing (0–100 scale) |

| Variable | Category | Sprawling Area (%) | Compact Area (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | ≤N$5000 | 54.8 | 19.6 | 37.2 |

| >N$5000 | 45.2 | 80.4 | 62.8 | |

| Education | Lower (Primary & Secondary) | 57 | 24.6 | 40.8 |

| Higher (College & University) | 43 | 75.4 | 59.2 | |

| Gender | Female | 52.2 | 49.8 | 51 |

| Male | 47.8 | 50.2 | 49 | |

| Age Group | Under 35 years | 58.2 | 55 | 56.6 |

| 35 years and above | 41.8 | 45 | 43.4 | |

| Driving Licence | Yes | 39.8 | 63 | 51.4 |

| No | 60.2 | 37 | 48.6 | |

| Shopping Location | Within Neighbourhood | 39 | 67.2 | 53.1 |

| Outside Neighbourhood | 61 | 32.8 | 46.9 |

| Variable | Neighbourhood Type | N | Min | Max | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population Density | Sprawling | 500 | 3.2 | 4 | 3.693 | 0.214 |

| Compact | 500 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 3.042 | 0.25 | |

| Number of Non-Work Trips (Past 7 Days) | Sprawling | 500 | 2 | 8 | 3.89 | 1.676 |

| Compact | 500 | 2 | 8 | 3.88 | 1.589 | |

| Sense of Belonging | Sprawling | 500 | 0 | 100 | 38.82 | 27.333 |

| Compact | 500 | 0 | 100 | 55.02 | 31.076 | |

| Perceived Attractiveness of Shopping Centres | Sprawling | 500 | 0 | 90 | 33.54 | 24.537 |

| Compact | 500 | 0 | 100 | 63.44 | 31.428 | |

| Perceived Attractiveness of Recreational Facilities | Sprawling | 500 | 0 | 100 | 20.42 | 19.545 |

| Compact | 500 | 0 | 100 | 56.12 | 29.609 | |

| Preference for Entertainment in Own Neighbourhood | Sprawling | 500 | 0 | 100 | 27.26 | 27.55 |

| Compact | 500 | 0 | 100 | 47.84 | 35.285 |

| Independent Variables | Chi-Square (Pearson) | df | p-Value | Cramer’s V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | 190.573 | 4 | <0.001 | 0.437 |

| Education | 141.191 | 6 | <0.001 | 0.376 |

| Driving License | 53.866 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.232 |

| Age | 54.448 | 5 | <0.001 | 0.233 |

| Gender | 0.576 | 1 | 0.448 | 0.024 |

| Shopping Location (neighbourhood/far) | 79.831 | 1 | <0.001 | 0.283 |

| Variable | Mean Rank (Sprawled) | Mean Rank (Compact) | U | Z | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense of belonging | 425.58 | 575.42 | 87,541.50 | –8.251 | <0.001 |

| Population Density | 738.88 | 262.12 | 5808.00 | –26.596 | <0.001 |

| Frequency of non-commuting trips | 499.32 | 501.68 | 124,409.00 | –0.139 | 0.890 |

| There are attractive shops or shopping centres in my neighbourhood | 369.22 | 631.78 | 59,359.50 | –14.459 | <0.001 |

| Attractiveness of social/recreational facilities in the neighbourhood | 335.42 | 665.58 | 42,462.00 | –18.207 | <0.001 |

| Preference for neighbourhood entertainment | 415.44 | 585.56 | 82,470.50 | –9.430 | <0.001 |

| B | S.E. | Wald | p | β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length/street density around home | 0.009 | 0.005 | 4.278 | 0.039 | 1.009 |

| Sense of belonging to the neighbourhood | 0.011 | 0.004 | 7.314 | 0.007 | 1.011 |

| Shops are too expensive as a reason for not shopping in the neighbourhood | −0.008 | 0.003 | 8.039 | 0.005 | 0.992 |

| I avoid boredom by visiting new places/people | −0.008 | 0.003 | 8.257 | 0.004 | 0.992 |

| Little security in the neighbourhood | −0.014 | 0.005 | 7.374 | 0.007 | 0.986 |

| Traffic safety perception when walking in the neighbourhood | −0.012 | 0.005 | 5.771 | 0.016 | 0.988 |

| Attractiveness of social/recreational facilities in the neighbourhood | 0.014 | 0.005 | 6.630 | 0.010 | 1.014 |

| Preference for neighbourhood entertainment | 0.693 | 0.204 | 11.582 | <0.001 | 1.999 |

| Perceived access to educational institutions | 0.009 | 0.004 | 3.956 | 0.047 | 1.009 |

| Income? (1) | −0.011 | 0.005 | 5.436 | 0.020 | 0.989 |

| Gender (1) | −0.477 | 0.201 | 5.612 | 0.018 | 0.621 |

| Number of driving licenses/households | −0.011 | 0.006 | 3.892 | 0.049 | 0.989 |

| Constant | 1.156 | 0.810 | 2.036 | 0.154 | 3.178 |

| Specification Tests | |||||

| Nagelkerke R Square | Omnibus Tests | ||||

| 0.208 | Chi-square | df | p | ||

| 84.158 | 12 | <0.001 | |||

| Hosmer and Lemeshow Test | |||||

| Observations | Chi-square | df | Sig. | ||

| N = 1000 | 6.701 | 8 | 0.569 | ||

| B | S.E. | Wald | p | β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length/street density around home | 0.010 | 0.005 | 4.750 | 0.029 | 1.010 |

| Little security in the neighbourhood | −0.010 | 0.003 | 9.181 | 0.002 | 0.990 |

| The shops or facilities are too expensive | −0.008 | 0.003 | 4.976 | 0.026 | 0.992 |

| I feel a sense of belonging to my neighbourhood | 0.010 | 0.004 | 5.321 | 0.021 | 1.010 |

| A preference to have entertainment far from the neighbourhood | −0.006 | 0.003 | 3.542 | 0.060 | 0.994 |

| I avoid boredom by visiting new places | −0.006 | 0.004 | 2.762 | 0.097 | 0.994 |

| There are attractive shops or shopping centres in my neighbourhood | 0.012 | 0.006 | 4.903 | 0.027 | 1.012 |

| Attractiveness of social/recreational facilities in the neighbourhood | 0.009 | 0.005 | 3.136 | 0.077 | 1.009 |

| Ease of navigating the neighbourhood by bicycle | 0.013 | 0.006 | 5.478 | 0.019 | 1.013 |

| No good social atmosphere as a reason for not shopping in the neighbourhood | −0.009 | 0.003 | 8.999 | 0.003 | 0.991 |

| Traffic safety perception when walking in the neighbourhood | −0.011 | 0.003 | 11.517 | <0.001 | 0.989 |

| Ease of Navigating the Neighbourhood by Car | 0.008 | 0.004 | 4.715 | 0.030 | 1.008 |

| Number of driving licenses/households | 0.011 | 0.005 | 4.691 | 0.030 | 1.011 |

| Household Size (Adults) | 0.172 | 0.083 | 4.229 | 0.040 | 1.187 |

| Age (1) | −0.011 | 0.006 | 3.627 | 0.057 | 0.989 |

| Gender (1) | −0.014 | 0.005 | 6.443 | 0.011 | 0.986 |

| Income (1) | 0.012 | 0.006 | 4.527 | 0.033 | 1.013 |

| Constant | −1.014 | 1.148 | 0.780 | 0.377 | 0.363 |

| Specification Tests | |||||

| Nagelkerke R Square | Omnibus Tests | ||||

| 0.214 | Chi-square | df | p | ||

| 87.371 | 17 | <0.001 | |||

| Hosmer and Lemeshow Test | |||||

| Observations | Chi-square | df | p | ||

| N = 1000 | 5.379 | 8 | 0.716 | ||

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | p | Collinearity Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | |||

| (Constant) | 27.873 | 6.203 | 4.493 | <0.001 | |||

| Intersection density around home | 0.110 | 0.048 | 0.094 | 2.269 | 0.024 | 0.946 | 1.057 |

| Sense of belonging to the neighbourhood | 0.112 | 0.043 | 0.112 | 2.615 | 0.009 | 0.892 | 1.122 |

| There are attractive shops or shopping centres in my neighbourhood | 0.101 | 0.047 | 0.090 | 2.158 | 0.031 | 0.941 | 1.062 |

| Attractive surrounding environment as a residential location choice | 0.137 | 0.052 | 0.111 | 2.632 | 0.009 | 0.909 | 1.100 |

| Perceived access to parks and recreational areas | 0.090 | 0.045 | 0.081 | 1.979 | 0.048 | 0.965 | 1.036 |

| The house is near to my workplace/school as a residential location choice | −0.069 | 0.035 | −0.080 | −1.972 | 0.049 | 0.976 | 1.025 |

| I have lived here since birth/childhood as a residential location choice | 0.081 | 0.033 | 0.101 | 2.455 | 0.014 | 0.962 | 1.039 |

| Traffic safety perception when walking in the neighbourhood | 6.338 | 2.956 | 0.113 | 2.144 | 0.033 | 0.587 | 1.704 |

| No good social atmosphere as a reason for not shopping in the neighbourhood | −0.111 | 0.038 | −0.120 | −2.941 | 0.003 | 0.972 | 1.029 |

| E-hailing usage frequency | 0.116 | 0.043 | 0.114 | 2.667 | 0.008 | 0.886 | 1.129 |

| Income | −0.153 | 0.040 | −0.159 | −3.816 | <0.001 | 0.937 | 1.067 |

| Driving license/household | −4.620 | 2.257 | −0.110 | −2.047 | 0.041 | 0.566 | 1.766 |

| Education | −0.139 | 0.052 | −0.110 | −2.680 | 0.008 | 0.956 | 1.046 |

| Model Summary | |||||||

| R | R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | |||||

| 0.462 | 0.213 | 24.789 | |||||

| ANOVA | |||||||

| Measures | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | ||

| Regression | 80,710.107 | 14 | 5765.008 | 9.382 | <0.001 | ||

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | p | Collinearity Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | |||

| (Constant) | 30.093 | 10.549 | 2.853 | 0.005 | |||

| Intersection density around home | 0.105 | 0.042 | 0.102 | 2.528 | 0.012 | 0.966 | 1.035 |

| Little security in the neighbourhood | −0.288 | 0.041 | −0.289 | −7.043 | <0.001 | 0.937 | 1.067 |

| Shops are too expensive as a reason for not shopping in the neighbourhood | −0.180 | 0.052 | −0.142 | −3.491 | <0.001 | 0.949 | 1.054 |

| There are attractive shops or shopping centres in my neighbourhood | 0.180 | 0.045 | 0.169 | 4.044 | <0.001 | 0.905 | 1.104 |

| I have lived here since birth/childhood as a residential location choice | 0.126 | 0.042 | 0.126 | 3.033 | 0.003 | 0.915 | 1.093 |

| Sense of belonging to the neighbourhood | 0.140 | 0.042 | 0.146 | 3.328 | <0.001 | 0.823 | 1.214 |

| Ease of navigating the neighbourhood by car | 0.214 | 0.076 | 0.115 | 2.803 | 0.005 | 0.944 | 1.060 |

| I avoid boredom by visiting new places as a reason for not shopping in the neighbourhood | −0.140 | 0.059 | −0.098 | −2.370 | 0.018 | 0.916 | 1.092 |

| The streets are not safe, as a reason for not walking in the neighbourhood | −0.189 | 0.069 | −0.112 | −2.744 | 0.006 | 0.949 | 1.054 |

| Proximity to e-hailing stop | 0.124 | 0.049 | 0.108 | 2.545 | 0.011 | 0.878 | 1.139 |

| Gender | 6.813 | 2.826 | 0.097 | 2.411 | 0.016 | 0.982 | 1.018 |

| Income | 0.127 | 0.043 | 0.123 | 2.986 | 0.003 | 0.934 | 1.071 |

| Number of driving licenses/households | 3.630 | 1.671 | 0.095 | 2.172 | 0.030 | 0.822 | 1.217 |

| Model Summary | |||||||

| R | R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | |||||

| 0.483 | 0.233 | 31.316 | |||||

| ANOVA | |||||||

| Measures | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | ||

| Regression | 144,638.150 | 13 | 11,126.012 | 11.345 | <0.001 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nuuyandja, H.; Pisa, N.; Masoumi, H.; Chakamera, C. The Relationships Between Land Use Characteristics, Neighbourhood Perceptions, Socio-Economic Factors and Travel Behaviour in Compact and Sprawled Neighbourhoods in Windhoek. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9100431

Nuuyandja H, Pisa N, Masoumi H, Chakamera C. The Relationships Between Land Use Characteristics, Neighbourhood Perceptions, Socio-Economic Factors and Travel Behaviour in Compact and Sprawled Neighbourhoods in Windhoek. Urban Science. 2025; 9(10):431. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9100431

Chicago/Turabian StyleNuuyandja, Hilma, Noleen Pisa, Houshmand Masoumi, and Chengete Chakamera. 2025. "The Relationships Between Land Use Characteristics, Neighbourhood Perceptions, Socio-Economic Factors and Travel Behaviour in Compact and Sprawled Neighbourhoods in Windhoek" Urban Science 9, no. 10: 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9100431

APA StyleNuuyandja, H., Pisa, N., Masoumi, H., & Chakamera, C. (2025). The Relationships Between Land Use Characteristics, Neighbourhood Perceptions, Socio-Economic Factors and Travel Behaviour in Compact and Sprawled Neighbourhoods in Windhoek. Urban Science, 9(10), 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9100431