Fragmented Realities: Middle-Class Perception Gaps and Environmental Indifference in Jakarta and Phnom Penh

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Context: Urban Fragmentation in the Southeast Asian City

2.1. Converging Crises: Flooding, Pollution, and Congestion

2.2. Contexts of Distrust: Governance, Politics, and Public Cynicism

2.3. The Rise of an Aspirational Middle Class

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Source and Parent Study

3.2. Sampling Strategy and Site Selection

3.3. Data Collection and Survey Instrument

3.4. Operationalizing Middle Class

3.5. Data Analysis

3.6. Methodological Justifications and Limitations

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Respondent Profiles and a Tale of Two Urban Middle Classes

4.2. The Perception Gap: Jakarta’s Insulation vs. Phnom Penh’s Pervasive Reality

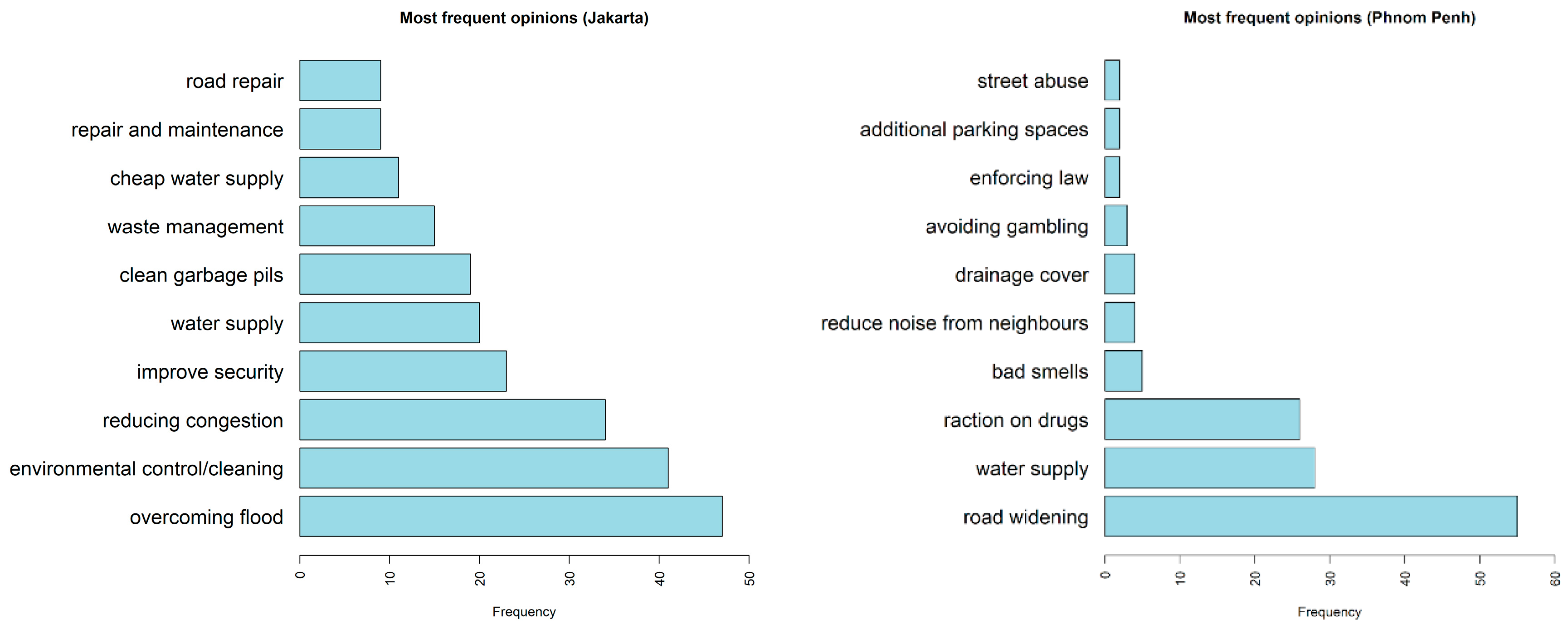

4.3. Agency and Silence: Interpreting Residents’ Voices

4.4. Intra-City Fragmentation: The Neighborhood as the World

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hadler, M. Environmental behaviors in a transatlantic view: Public and private actions in the United States, Canada, Germany, and the Czech republic, 1993–2010. Int. J. Sociol. 2013, 43, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, A.; Vogl, D. Two decades of measuring environmental attitudes: A comparative analysis of 33 countries. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malier, H. No (sociological) excuses for not going green: How do environmental activists make sense of social inequalities and relate to the working class? Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2021, 24, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koning, J.I.J.C.; Crul, M.R.M.; Wever, R.; Brezet, J.C. Sustainable consumption in Vietnam: An explorative study among the urban middle class. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwan, C.; Hughes, A.; Bek, D. Theorising middle class consumption from the global South: A study of everyday ethics in South Africa’s Western Cape. Geoforum 2015, 67, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Never, B.; Albert, J.R.G. Unmasking the middle class in the Philippines: Aspirations, lifestyles and prospects for sustainable consumption. Asian Stud. Rev. 2021, 45, 594–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mialhe, F.; Gunnell, Y.; Navratil, O.; Choi, D.; Sovann, C.; Lejot, J.; Gaudou, B.; Se, B.; Landon, N. Spatial growth of Phnom Penh, Cambodia (1973–2015): Patterns, rates and socio-ecological consequences. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustiadi, E.; Pravitasari, A.E.; Setiawan, Y.; Mulya, S.P.; Pribadi, D.O.; Tsutsumida, N. Impact of continuous Jakarta megacity urban expansion on the formation of the Jakarta-Bandung conurbation over the rice farm regions. Cities 2021, 111, 103000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Octavianti, T.; Charles, K. The evolution of Jakarta’s flood policy over the past 400 years: The lock-in of infrastructural solutions. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2019, 37, 1102–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Cambodia: Achieving the Potential of Urbanization. 2018. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/30867/127247-REVISED-CambodiaUrbanizationReportEnfinal.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Brenner, N.; Schmid, C. Towards a new epistemology of the urban. City 2015, 19, 151–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paling, W. Planning a future for Phnom Penh: Mega projects, aid dependence and disjointed governance. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 2889–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y. An urban explanation of Jokowi’s rise: Implications for politics and governance in post-Suharto Indonesia. J. Curr. Southeast Asian Aff. 2021, 40, 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padawangi, R. Urban Development in Southeast Asia; Elements in Politics and Society in Southeast Asia; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira, T.P. City of Walls: Crime, Segregation, and Citizenship in São Paulo; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, S.; Marvin, S. Splintering Urbanism: Networked Infrastructures, Technological Mobilities and the Urban Condition; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, R.; Masron, I.N. Jakarta: A city of cities. Cities 2020, 106, 102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manurung, H. The Effect of Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaya Purnama Leadership Style on Indonesia Democracy (2012–2016). In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Social Sciences and the Humanities, Jakarta, Indonesia, 18–20 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wijaya, C.A. Reclamation Project the Answer to Jakarta Bay Pollution Woes: Ahok. The Jakarta Post. 18 April 2016. Available online: https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2016/04/18/reclamation-project-the-answer-to-jakarta-bay-pollution-woes-ahok.html (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Aziza, K.S. Bappenas: Kerugian Akibat Macet Jakarta Rp 67 Triliun Per Tahun. Kompas. 6 October 2017. Available online: https://ekonomi.kompas.com/read/2017/10/06/054007626/bappenas-kerugian-akibat-macet-jakarta-rp-670-triliun-per-tahun (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- CEIC. Indonesia Number of Motor Vehicles: Passenger Cars: Jakarta. CEIC Data. 2018. Available online: https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indonesia/number-of-motor-vehicle-registered-passenger-cars/no-of-motor-vehicles-passenger-cars-jakarta (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Dewi, B.K. Menangi Tuntutan Hak Udara Bersih Jakarta, Warga Desak Langkah Nyata Pemerintah. Kompas. 8 October 2021. Available online: https://www.kompas.com/sains/read/2021/10/08/213003723/menangi-tuntutan-hak-udara-bersih-jakarta-warga-desak-langkah-nyata?page=all (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Asian Development Bank. Cambodia: Transport Sector Assessment, Strategy, and Roadmap. 2019. Available online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/529231/cambodia-transport-assessment-strategy-road-map.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Koeng, S.; Sharp, A.; Hul, S.; Kuok, F. Plastic bag management options in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. GMSARN Int. J. 2020, 14, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, C.B. Phnom Penh kaleidoscope: Construction boom, material itineraries and changing scales in urban Cambodia. East Asian Sci. Technol. Soc. Int. J. 2021, 15, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S. Urban speculation, economic openness, and market experiments in Phnom Penh. Positions Asia Crit. 2017, 25, 645–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukmana, D. The change and transformation of Indonesian spatial planning after Suharto’s new order regime: The case of the Jakarta metropolitan area. Int. Plan. Stud. 2015, 20, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.V.; Duflo, E. What is middle class about the middle classes around the world? J. Econ. Perspect. 2008, 22, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharas, H. The Emerging Middle Class in Developing Countries. OECD Development Centre Working Paper No.285 DEV/DOC 2. 2010. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2010/01/the-emerging-middle-class-in-developing-countries_g17a1d87/5kmmp8lncrns-en.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Percival, P.; Waley, P. Articulating intra-Asian urbanism: The production of satellite cities in Phnom Penh. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 2873–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adorno, T. The Culture Industry: Selected Essays on Mass Culture; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Benita, F. Exploring non-mandatory travel behavior in Jakarta City: Travel time, trip frequency, and socio-demographic influences. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2023, 21, 100896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddart-Kennedy, E.; Beckley, T.M.; McFarlane, B.L.; Nadeau, S. Rural-urban differences in environmental concern in Canada. Rural Sociol. 2009, 74, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosius, J.D.; Gilderbloom, J.I. Who’s greener? Comparing urban and suburban residents’ environmental behaviour and concern. Local Environ. 2015, 20, 836–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrianjaka, R.R. Middle-Class Composition and Growth in Middle-Income Countries; Working Paper No. 753; Asian Development Bank Institute: Manila, Philippines, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank; Government of Australia. Aspiring Indonesia—Expanding the Middle Class. 2019. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/indonesia/publication/aspiring-indonesia-expanding-the-middle-class (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Sedjati, R.S.; Permana, I.S.; Pertiwi, I. Effects of Price and Economic Factors on the Demand of Private Cars in Jakarta Indonesia. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2017, 8, 724–730. [Google Scholar]

- Agresti, A. Categorical Data Analysis, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ramli, P.; Indradjati, P.N. Dampak Spasial Komunitas Berpagar terhadap Kawasan Perkotaan Mamminasata. Tata Loka 2021, 23, 329–343. [Google Scholar]

- Nop, S.; Thornton, A. Community participation in contemporary urban planning in Cambodia: The examples of Khmounh and Kouk Roka neighbourhoods in Phnom Penh. Cities 2020, 103, 102770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coy, M. Gated communities and urban fragmentation in Latin America: The Brazilian experience. GeoJournal 2006, 66, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kracker Selzer, A.; Heller, P. The spatial dynamics of middle-class formation in postapartheid South Africa: Enclavization and fragmentation in Johannesburg. In Political Power and Social Theory; Go, J., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2010; Volume 21, pp. 171–208. [Google Scholar]

| Jakarta | Phnom Penh | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| summary statistic/frequency | |||

| Age | Age | ||

| min | 18 | 18 | min |

| mean | 44.31 | 43.65 | mean |

| max | 83 | 96 | max |

| sd | 12.74 | 13.88 | sd |

| Gender | Gender | ||

| Male | 33.65% | 46.26% | Male |

| Female | 66.35% | 53.74% | Female |

| Household monthly income | Household monthly income | ||

| Prefer not to disclose | 20.38% | 9.85% | Prefer not to disclose |

| 0–268 (USD) * | 50.87% | 2.19% | No income |

| 269–534 USD (USD) * | 25.77% | 5.20% | 1–249 (USD) |

| 535–800 (USD) * | 2.40% | 26.19% | 250–499 (USD) * |

| >800 (USD) * | 0.58% | 28.74% | 500–749 (USD) * |

| 11.77% | 750–999 (USD) * | ||

| 8.03% | 1000–1500 (USD) * | ||

| 8.03% | >1500 (USD) * | ||

| Education level | Education level | ||

| No education | 4.42% | 4.65% | No education * |

| Elementary school | 16.73% | 29.29% | Elementary school * |

| Junior High school * | 21.06% | 30.93% | Lower Secondary * |

| Senior High school * | 42.69% | 23.45% | Upper Secondary * |

| Technical school/Diploma * | 5% | 2.10% | Others (associate degree, technical school, etc.) * |

| University * | 9.04% | 7.76% | University * |

| Postgraduate * | 1.06% | 1.82% | Postgraduate * |

| Vehicle Ownership | Vehicle Ownership | ||

| No vehicle | 18.14% | 4.47% | No vehicle |

| Car * | 1.44% | 0.64% | Car * |

| Car and motorbike * | 9.88% | 33.57% | Car and motorbike * |

| Motorbike * | 70.54% | 49.45% | Motorbike * |

| 11.87% | Others (tricycle, remork motor, etc.) * | ||

| Total respondents | 1040 | 1096 | Total respondents |

| Middle class | 385 (37.02%) | 907 (82.76%) | Middle class |

| Jakarta | Phnom Penh | |

|---|---|---|

| p-value | p-value | |

| Air Pollution | 0.049 | 0.573 |

| Flooding | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| Foul smells | 0.020 | 0.697 |

| Noise pollution | 0.001 | 0.471 |

| Water pollution | 0.009 | 0.159 |

| Neighborhood | Waste | Flooding | Traffic | Total Issues Mentioned |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Benhil | 11 (26.2%) | 11 (26.2%) | 20 (47.6%) | 42 |

| 2. Cengkareng | 5 (12.2%) | 28 (68.3%) | 8 (19.5%) | 41 |

| 3. Tanah Merah | 5 (62.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | 2 (25%) | 8 |

| Total | 21 | 40 | 30 | 91 |

| Neighborhood | Roads | Drainage/Sewer | Security/Law | Environment/Waste | Total Issues Mentioned |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Boeng Trabaek | 1 (12.5%) | 2 (25%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) | 8 |

| 2. Tuol Sangkae | 18 (30%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 60 |

| 3. Krang Thnong | 35 (35.7%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (13.3%) | 1 (1%) | 98 |

| 4. Dangkao | 2 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (30%) | 0 (0%) | 10 |

| Total | 56 | 2 | 29 | 1 | 176 |

| Cengkareng—Benhil | Tanah Merah—Benhil | Tanah Merah—Cengkareng | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air Poll. | C > B (***) | TM > B (***) | ns |

| Flooding | B > C (**) | TM > B (***) | TM > C (***) |

| Noise poll. | B > C (***) | ns | TM > C (*) |

| Traff. cong. | B > C (***) | B > TM (**) | ns |

| Water poll. | B > C (**) | TM > B (***) | TM > C (***) |

| Foul smells | B > C (***) | ns | TM > C (***) |

| Tuol Sangkae—Boeng Trabaek | Krang Thnong—Boeng Trabaek | Dangkao—Boeng Trabaek | Krang Thnong—Tuol Sangkae | Dangkao—Tuol Sangkae | Dangkao—Krang Thnong | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air Poll. | ns | KT > BT (***) | ns | KT > TS (*) | ns | KT > D (*) |

| Flooding | ns | ns | D > BT (***) | ns | D > TS (***) | D > KT (***) |

| Noise poll. | ns | ns | BT > D (**) | ns | TS > D (*) | KT > D (**) |

| Traff. cong. | ns | BT > KT (***) | BT > D (*) | TS > KT (***) | TS > D (*) | D > KT (*) |

| Water poll. | ns | ns | BT > D (***) | ns | TS > D (***) | KT > D (*) |

| Foul smells | ns | ns | D > BT (***) | ns | D > TS (***) | D > KT (***) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benita, F.; Yaacob, H.; Martinez, R. Fragmented Realities: Middle-Class Perception Gaps and Environmental Indifference in Jakarta and Phnom Penh. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9100427

Benita F, Yaacob H, Martinez R. Fragmented Realities: Middle-Class Perception Gaps and Environmental Indifference in Jakarta and Phnom Penh. Urban Science. 2025; 9(10):427. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9100427

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenita, Francisco, Hamzah Yaacob, and Rafael Martinez. 2025. "Fragmented Realities: Middle-Class Perception Gaps and Environmental Indifference in Jakarta and Phnom Penh" Urban Science 9, no. 10: 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9100427

APA StyleBenita, F., Yaacob, H., & Martinez, R. (2025). Fragmented Realities: Middle-Class Perception Gaps and Environmental Indifference in Jakarta and Phnom Penh. Urban Science, 9(10), 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci9100427