1. Introduction

The global spread of gated communities has emerged as one of the most significant urban transformations of recent decades [

1,

2], with particularly complex manifestations in Middle Eastern cities. These privatised residential developments, characterised by restricted access, exclusive amenities, and socio-economic homogeneity, have become powerful symbols of contemporary urban development [

3,

4]. Their expansion reflects broader transformation in land use, urban governance, and spatial equity [

5,

6]. This proliferation is not merely a trend in residential architecture but a profound spatial expression of deeper socio-economic transformations. Scholars are increasingly interpreting this phenomenon through discussions of spatial justice and neoliberal urban governance [

7]. Spatial justice concerns the fair distribution of resources and opportunities in space, arguing that urban form is deeply implicated in producing social inequality. From this perspective, gated communities can be seen as a source of injustice, creating privatised areas of privilege that actively fragment the urban fabric and restrict access to amenities for the wider public. This is driven by a neoliberal concept of urban development, where market forces and private sector control prevail in planning, often at the expense of public needs [

7].

In the Middle East, this manifests in distinct ways. In the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, for instance, gated communities emerged historically as spatial instruments of state governance, primarily to accommodate and segregate Western expatriate workers during the mid-20th-century oil boom [

2,

8]. This model reinforced class divisions while serving both economic requirements and socio-cultural preservation objectives [

9]. Across the region, gated communities share several common features: they are generally market-driven, cater to upper middle class or elite populations, provide controlled access and private amenities, and reflect broader socio-economic inequalities. Despite these commonalities, significant variations exist. In the GCC, developments are often large-scale, state-supported, and serve as tools of socio-spatial regulation. In contrast, in countries without substantial oil wealth, such as Jordan, developments tend to be smaller, privately funded, and shaped primarily by speculative investment and regional capital flows. Recognising these similarities and differences provides a framework for understanding gated urbanism as a heterogeneous but regionally embedded phenomenon.

In particular, there is limited comparative work that distinguishes between the state-supported mega-developments of the GCC countries and the more fragmented, market-led forms found in countries like Jordan. While studies on Jordan are increasing, they often focus narrowly on resident motivations or isolated case studies [

10,

11]. A synthesised analysis of regional expert perspectives on the socio-spatial impacts and governance challenges of these developments is notably absent. By situating Jordan within a regional continuum of gated urbanism, this article extends debates beyond country-specific cases toward a comparative Middle Eastern perspective. This gap constrains our ability to understand gated communities not simply as isolated developments but as spatial expressions of broader governance failures, investment flows, and socio-political dynamics across the Middle East. This study addresses that gap by examining the socio-spatial implications of gated urbanism in selected Middle Eastern contexts, with a particular focus on Jordan.

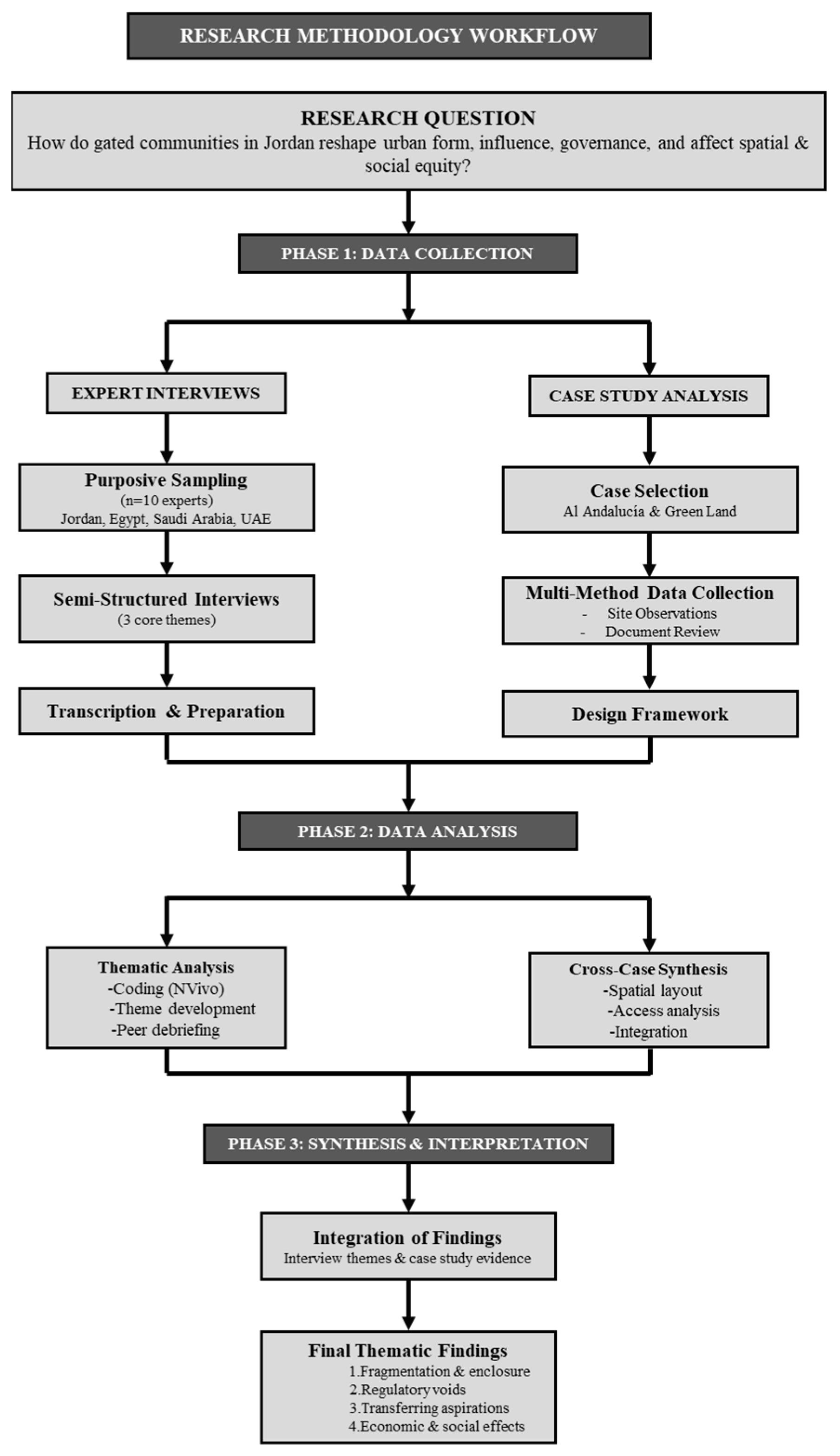

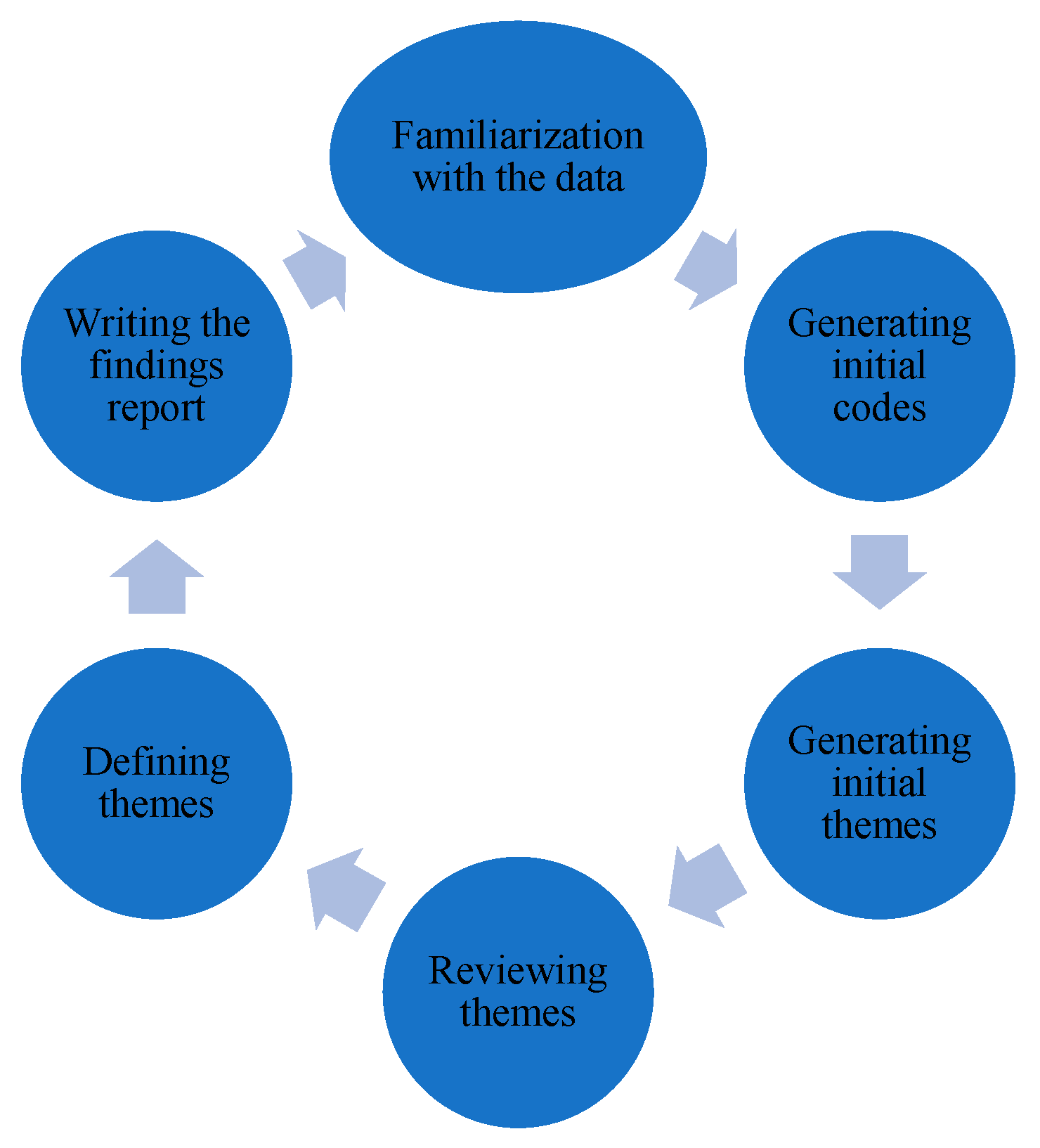

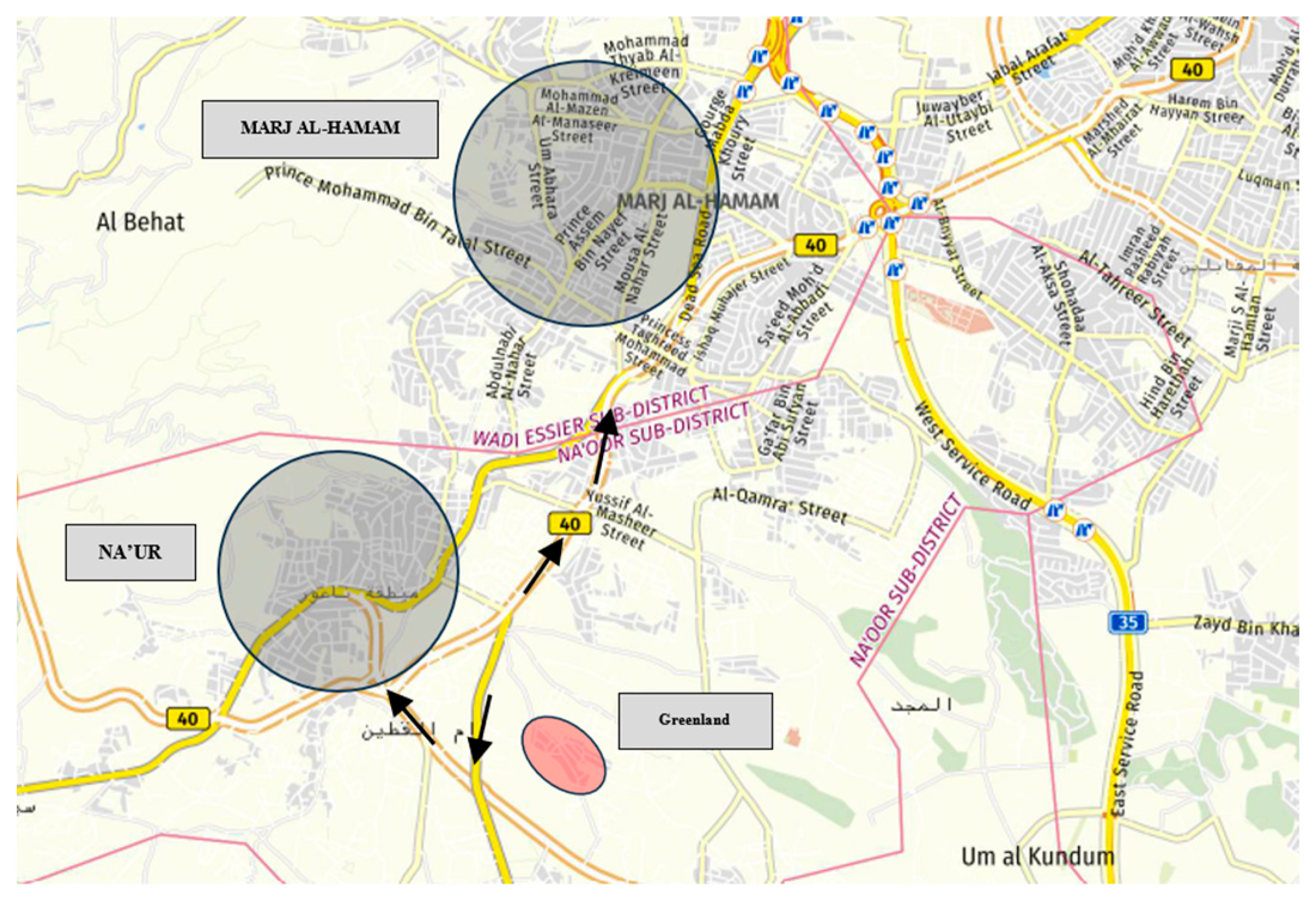

To support this discussion, the central research question guiding this analysis is: How do gated communities in the Middle East, particularly in Jordan, guide urban form, influence governance frameworks, and affect spatial and social equity? To address this, the study employs a qualitative, multi-scalar methodology that combines thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews with urban experts across the region and a comparative case study analysis of two prominent gated developments in Amman: Al Andalucía and Green Land. A total of 10 semi-structured interviews were conducted with urban planners, architects, authority personnel, and academics, selected for their professional expertise and direct involvement in housing and urban development across Jordan and the wider Middle East. This composition ensured coverage of both technical and academic perspectives.

The selection of Al Andalucía and Green Land is deliberate, as the two cases illustrate contrasting models of gated urbanism that directly connect with the research questions. Al Andalucía represents a more exclusive, spatially segregated development designed around luxury branding and seclusion. Whereas Green Land demonstrates a hybrid, moderately integrative model influenced by progressive investment and diverse ownership structures. Their comparison highlights how different governance arrangements and market requirements produce contrasted socio-spatial outcomes, making them valuable cases for understanding the broader continuum of gated development across Jordan and the Middle East.

The findings reveal a heterogeneous and context-dependent phenomenon, influenced by infrastructural deficiencies, neoliberal urban policies, and evolving consumer preferences. While these developments cater to demands for security, exclusivity, and modern living standards, they simultaneously exacerbate socio-spatial inequalities by reinforcing exclusionary practices, urban fragmentation, and reduced urban integration. The selected case studies are large-scale, privately developed residences located on the urban periphery of Amman. While Al Andalucía exemplifies spatial seclusion and luxury branding, Green Land presents a more diversified and economically integrative model [

12]. These cases, paired with thematic insights from expert interviews, illustrate how gated developments are not merely residential typologies but spatial expressions of broader governance, planning, and investment structures [

3,

13].

Jordan’s gated development model offers particularly valuable insights into this regional phenomenon. The country’s lack of substantial oil revenues has led to a distinctive model where these communities are largely driven by the private sector, influenced by speculative real estate aspects and regional capital flows [

12]. Major projects, such as the Abdali development, which is significantly funded by UAE investors, exemplify how Jordan’s gated communities have become embedded in regional investment networks, catering primarily to local upper middle class desires for prestige and security [

6]. This has created what recent studies term an “infectious divide”, a pattern of urban development where privatised residential spaces increasingly dominate city peripheries, exacerbating socio-spatial inequalities [

9].

By combining expert interviews with contrasting case studies of Al Andalucía and Green Land, this study provides new insights into how governance structures, market requirements, and design choices influence socio-spatial inequality and urban integration. It thereby addresses a notable gap in comparative analyses of gated urbanism in the Middle East, particularly between state-supported GCC developments and market-driven Jordanian projects. These findings highlight the need for planning frameworks that promote spatial integration, equity, and long-term urban resilience [

11,

14]. These findings offer both academic contributions to debates on exclusive urbanism and practical guidance for planning policies that promote equity, connectivity, and sustainable urban development.

2. Literature Review

The emergence of gated communities represents a significant global urban transformation, evolving from a post-World War II American phenomenon into a worldwide trend driven by desires for security, exclusivity, and socio-economic distinction [

8,

9]. Scholars highlight common themes of social segregation, spatial fragmentation, and privatisation of public space [

4,

15,

16]. They are more widely critiqued for exacerbating urban fragmentation, social segregation, and spatial inequality [

17]. While critiques often emphasise exclusionary impacts and urban inequality, some argue these developments can also provide residents with safety, cohesion, and enhanced property values [

18,

19]. This global literature establishes gated communities as spatial expressions of neoliberal urban governance, where privatised solutions fill voids left by public planning, often at the cost of broader spatial justice [

20,

21].

The Middle East presents distinctive trajectories influenced by oil wealth, migration, and socio-political structures. In the GCC, early merchant enclosures and post-oil expatriate compounds evolved into large-scale gated developments catering to foreign workers and elites [

2,

22,

23]. Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and Qatar illustrate how cultural conservatism and expatriate demand drove gated housing models, while in Egypt, Lebanon, and Turkey, economic liberalisation and weak public provision positioned gating as both a luxury commodity and a coping strategy [

5,

24,

25]. Scholars consistently emphasised the role of private developers, weak planning frameworks, and neoliberal housing policies in reinforcing urban inequality and socio-spatial segregation [

6,

26]. Despite regional diversity, the Middle East shares a dual legacy of exclusivity and fragmentation across its borders.

Jordan’s gated developments emerged later, initially as family compounds in the 1990s before evolving into private sector-led projects after 2009 [

10]. Unlike GCC contexts centred on expatriates, these communities target Jordan’s middle- and upper-middle classes, marketed as prestigious, secure, and modern housing [

13,

27]. Studies indicate the existence of different typologies, such as “mini” communities in wealthy urban districts and “mega” developments on Amman’s periphery, which are both characterised by exclusivity and weak regulation [

13]. While motivations such as privacy, investment, and lifestyle dominate, concerns about urban fragmentation, resource use, and social segregation remain underexplored [

11]. Recent mega-projects, such as Abdali, Al Andalucía, and Jordan Gate, highlight the influence of the GCC capital and speculative real estate [

6,

28]. However, a significant gap remains in understanding the socio-spatial impacts of these communities on the surrounding urban fabric and in synthesising regional expert perspectives on their development. This study addresses this gap by combining qualitative insights from urban experts across the Middle East with a comparative case study analysis of two major Jordanian developments, Al Andalucía and Green Land, to elucidate their role in reshaping urban form, governance, and equity in Jordan and the wider region.

4. Results

This section presents an integrated analysis of findings from the expert interviews and case studies. The empirical observations from Al Andalucía and Green Land provide the foundational context, while insights from regional experts are merged throughout to interpret, contextualise, and explain these patterns within broader Middle Eastern urban trends. This approach enables a constructive examination of how macro-level expert perspectives are manifested in specific local contexts.

4.1. Case Study 1: Al Andalucía

Al Andalucía, developed between 2005 and 2013, is a gated villa compound approximately 20 km south of central Amman and represents one of Jordan’s first large-scale gated communities [

11]. Located along the Airport Road corridor, the development spans 800,000 square meters and comprises 588 villas, surrounded by a concrete perimeter wall and a single gated access point (

Figure 3). It was selected for this study as a paradigm case due to its high enclosure, luxury branding, and socio-spatial segregation, which exemplify common patterns of gated urbanism in Jordan.

This case is critically significant to the research question concerning how gated communities reshape urban form and reinforce inequalities. Site observations confirmed a strict hierarchical access structure, featuring a single main entrance for residents and visitors, as well as a separate service entrance for deliveries and staff, both of which were heavily controlled by security personnel. Its spatial layout is characterised by low permeability and one entrance, reinforcing enclosure, and it was built on reclassified agricultural land, reflecting weak land use regulation in Jordan (

Figure 4).

The physical form of Al Andalucía exemplifies the theme of spatial fragmentation identified by regional experts. Its high walls and controlled access visually reinforce the social exclusion and perception of elitism discussed in interviews. One expert remarked: “It’s like another city behind walls—residents enjoy better infrastructure, while neighbours remain excluded” (Interview 7, Jordan). This expert perspective aligns directly with the site’s observed isolation, confirming its function as what multiple interviewees termed a “social island.” Additionally, the expert perspective aligns directly with the site’s observed isolation, empirically demonstrating how such developments affect urban form by creating partitioned, disconnected territories that exacerbate socio-spatial inequalities. This sense of disconnection was empirically evidenced by poor access to public services, limited retail options, and the observed necessity for residents to commute to Madaba (9.7 km away) for basic goods. The internal road network spans approximately 1.2 km, and no local service facilities were present within the community, further highlighting disparities with surrounding areas.

Furthermore, Al Andalucía directly illustrates the governance gaps highlighted in the research question. Despite its internal amenities, including a centrally located recreational area designed to enhance internal social interaction, the development suffers from pronounced external social disconnection. This observation validates the expert-identified paradox of strong internal social cohesion within gated communities, which occurs alongside weakened external social ties. The development’s approval on reclassified land was attributed by experts to a significant governance gap. As one expert from Egypt noted, “

These projects follow investor logic—not planning logic” (Interview 3), a point that directly evidences how gated communities thrive under conditions of planning gaps, influencing the governance framework by operating outside strategic urban integration efforts (

Figure 5).

4.2. Case Study 2: Green Land

Developed in 2008 by a prominent Jordanian investor, Green Land spans 400,000 square meters and comprises approximately 500 units. It was deliberately selected as a comparative case representing a hybrid model of development in Jordan. Unlike Al Andalucía, it adopts a moderately integrated approach, featuring a semi-open layout, partial plot-based development, and greater architectural diversity (

Figure 6). Its design, potentially reflecting lessons from earlier projects, aims for moderate connectivity with surrounding areas while providing security. Also, it is located closer to central Amman (12.6 km) in Na’ur area and is enclosed by a wire fence and boom gate rather than a solid wall, presenting a more semi-open layout.

The site observations revealed a noticeably different atmosphere; the wire fence allows for visual connectivity with the surrounding area, and the main gate was frequently observed to be open during the day. Green Land’s physical characteristics reflect a more moderate approach to enclosure. Its partial build-out model, with 50% of plots sold to individuals, has resulted in greater architectural diversity than the homogenous Al Andalucía (

Figure 7).

This observed variation aligns with expert insights about diverse development models emerging in Jordan. The more urbanised setting provides better access to nearby towns like Na’ur and Marj Al Hamam, supporting the expert view that some communities maintain stronger connections with their surroundings. Despite these advantages, interviewees noted that Green Land still reinforces exclusivity and exhibits limited transportation options and inconsistent service delivery. Interviewees noted that Green Land “

still reinforces exclusivity” and exhibits “

limited transportation options and inconsistent service delivery.” This expert analysis helps qualify the on-the-ground observations, preventing an overstatement of its integrative qualities. The internal recreation area was described as less centralised than Al Andalucía’s, reducing its effectiveness in fostering community-wide interaction, an observation that nuances the expert theme of internal cohesion (

Figure 8). The internal recreation area was described as less centralised, reducing its effectiveness in fostering community-wide interaction compared to Al Andalucía.

4.3. Synthesised Comparative Themes

The integrated analysis of both case studies and expert interviews reveals four dominant themes that characterise gated urbanism in Jordan and the wider region, as summarised in (

Table 1). These themes emerged not as pre-determined categories but as consistent patterns derived from the relationship between empirical observation and professional interpretation.

First, the theme of Fragmentation and Enclosure was empirically observed in both cases through walls and access controls, and was explicitly identified by experts as creating “social islands” that weaken external social ties. Second, the theme of Regulatory Voids and Governance Limitations was evident in the development of the case studies on reclassified land, and was critically explained by experts who cited a consistent “lack of effective regulation” and “weak zoning enforcement” across the region. Third, the theme of aspirational urban identity was observed in the marketing and architectural imitation of GCC models (particularly in Al Andalucía) and was explicitly framed by experts as an “aspirational” drive for “privacy, order, and Gulf-style exclusivity” tied to social status. Fourth, the theme of inconsistent economic and Social Outcomes was observed in the limited local economic activity around both sites and was critically analysed by experts, who noted that benefits are “largely internal,” with “uneven” distribution effects that are insufficient to stimulate broader economic transformation.

The comparative analysis of Al Andalucía and Green Land demonstrates how the observed case characteristics correspond to the four core themes derived from expert interviews. For instance, Al Andalucía’s spatial enclosure and high walls directly reflect the urban form and social fragmentation theme, while Green Land’s semi-open layout shows a moderate approach to integration. Governance differences, aspirational identities, and economic outcomes align with patterns highlighted by regional experts, confirming the thematic findings across different development models.

In conclusion, both projects highlight:

The reliance on private capital and developer discretion;

A lack of cohesive urban policy or regulation for gated communities;

The persistence of social and spatial divides, despite differing scales and locations.

The analysis highlights that the current lack of cohesive urban policy directly enables the governance gaps and spatial fragmentation documented in both cases. The findings suggest that the demonstrated negative outcomes, such as economic insulation and social disconnection, could be mitigated by stronger governance mechanisms, including clearer zoning enforcement, requirements for integrating gated projects into municipal planning frameworks, and policies mandating permeability and mixed-use development.

4.4. Thematic Findings from Expert Interviews

The thematic analysis of ten semi-structured interviews with regional experts initially yielded six distinct themes, each addressing a key dimension of gated community development in the Middle East. These initial themes, along with their prevalence in the data, are summarised in (

Table 2).

While the number of interviews was limited to ten, thematic saturation was observed, as no new themes emerged beyond the final interviews. The sample included experts distributed across the four focus countries: Jordan (n = 6), Egypt (n = 1), Saudi Arabia (n = 1), and the UAE (n = 2), which ensured that the perspectives represented were regionally balanced and captured key contextual differences. The expert panel also represented multiple professional backgrounds, including three urban planners, five academic researchers specialising in Middle Eastern urban studies, and two architects with direct experience in gated community projects, including one working in municipal authority. While selected quotes illustrate key themes, the analysis integrates insights from all participants across countries and professions, ensuring that findings reflect both regional diversity and professional expertise, thereby mitigating potential bias. Based on thematic overlap, narrative coherence, and alignment with the study’s research aims, these six themes were subsequently consolidated into four core domains to structure the discussion of findings. This process was primarily driven by the identification of significant thematic overlap and redundancy among the initial codes. For instance, the themes ‘Role distribution in development’ and ‘Regulations involved’ were integrated into the broader domain of ‘Governance and Regulation’, as both pertained to the institutional and actor-oriented mechanisms influencing gated community development. Furthermore, themes were evaluated based on their analytical scope. The theme ‘Reasons for development’, which encompassed drivers such as security and exclusivity, was integrated into the more comprehensive domain of ‘Aspirations and Urban Identity’ to reflect the deeper social and cultural motivations underlying gated living. Finally, considerations of narrative coherence and alignment with the study’s research aims ensured that the resulting thematic structure, centred on urban form, governance, aspirations, and economic effects. The consolidation ensured transparency and reduced redundancy while preserving the richness of the data.

The thematic coding of interview transcripts is summarised in

Table 3, including brief descriptions that reflect their analytical focus.

The four core domains: Impacts on Urban Form and Social Fabric, Governance and Regulation, Transformations in Spatial Aspirations and Urban Identity, and Economic and Social Effects, are correlated. Urban form and social fabric are affected by governance frameworks, as weak regulatory oversight or informal approvals influence the spatial layout, enclosure strategies, and accessibility of gated communities. These spatial configurations, in turn, influence residents’ aspirational identities, as the built environment reflects and reinforces desires for privacy, status, and exclusivity. The aspirational and socio-cultural aspects interrelate with economic outcomes, determining the distribution of local employment generation and access to services. On the other hand, economic constraints and market requirements control urban form, influencing investment strategies, plot allocation, and the degree of integration with surrounding areas.

6. Conclusions

This study has examined the socio-spatial impacts of gated communities in the Middle East through a combination of expert interviews and case study analysis of Al Andalucía and Green Land in Jordan. The findings demonstrate that gated communities are not only residential typologies but also spatial manifestations of broader social, economic, and governance challenges within the region’s urban structures. Furthermore, the results directly address the study’s research question by demonstrating how gated communities in the Middle East, particularly in Jordan, affect urban form, reinforce socio-spatial inequalities, and reflect regulatory and economic governance gaps, as interpreted through expert perspectives and empirical case studies.

Specifically, the analysis reveals that these developments consistently reinforce spatial fragmentation and social exclusion, despite also fostering internal social cohesion. Furthermore, they provide limited and uneven economic benefits that are largely concentrated within their boundaries, a phenomenon that thrives under conditions of planning voids and minimal regulatory frameworks for urban integration.

Despite some differences in scale and development strategies between case studies, both illustrate how market-led residential urbanism, particularly when unregulated, can weaken inclusive, connected, and sustainable urban development in Middle Eastern contexts. Building on these diagnostic findings, the study concludes by outlining a conceptual framework for envisioning urban integration. This framework, illustrated in (

Figure 9), translates the research themes into a spatial vocabulary to stimulate discussion on potential mitigation pathways. It visualises a hypothetical scenario for Al Andalucía, exploring how interventions like semi-permeable boundaries and improved pedestrian connectivity might hypothetically address the identified issues of fragmentation. The value of this conceptual exercise lies not in serving as a practical blueprint, which would require extensive resident engagement and feasibility studies, but rather as a scholarly tool to bridge critical analysis with policy imagination. It serves to demonstrate the applied value of qualitative research findings and to propose a direction for future investigative work, including the vital next step of incorporating resident perspectives into the co-design of more inclusive urban strategies.

This approach is illustrated in

Figure 9, which conceptualises how boundary retrofitting and spatial linkages could enhance urban integration (

Figure 10). This figure does not depict a final design but serves as a visual hypothesis to guide future research and policy dialogue on retrofit possibilities for existing fragmented urban forms.

This study is limited by its regional scope and qualitative design. While experts from Jordan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates offered diverse insights, perspectives from other Middle Eastern contexts were not included. The findings, based on ten expert interviews and two case studies, are context-specific and not intended for broad generalisation. Additionally, the study focused on expert and spatial perspectives, without incorporating the views of residents or local municipal actors. Future research could benefit from broader stakeholder inclusion and mixed-methods approaches to further validate and expand on these findings.

While the empirical focus of this study was on Jordan, the inclusion of expert perspectives from across the region extends the implications to a broader context. The research confirms the notion of a “dual legacy of exclusivity and fragmentation” across the Middle East, while highlighting the range of planning regimes and economic models that shape it. Specifically, the findings reveal that the GCC’s state-supported mega-developments and Jordan’s private sector-driven, fragmented projects represent two ends of a regional continuum of gated urbanism. In doing so, the study addresses a key gap in the literature by moving beyond country-specific cases to offer a synthesised, regional perspective. Future research should build on these comparative studies and integrate the perspectives of residents and municipal actors to more fully capture the lived experience and governance dynamics of these increasingly pervasive urban forms.

To mitigate the socio-spatial challenges posed by gated communities, several policy directions are proposed. It is crucial to strengthen regulatory frameworks by introducing clear municipal guidelines that mandate integration, service provision, and accessibility. Furthermore, planning policies should promote spatial integration by incentivising designs that support permeability, shared public amenities, and pedestrian connections with surrounding urban areas. A balance must be struck between public and private interests through mechanisms that align investment goals with the provision of public infrastructure and spatial equity. This requires context-sensitive planning that avoids replicating large-scale GCC models in lower-capacity cities; instead, it adapts strategies to fit local realities. Ultimately, supporting mixed-income and mixed-tenure housing is crucial for diversifying income groups, reducing exclusivity, and fostering urban cohesion.

As Middle Eastern cities continue to urbanise under the pressures of global capital, demographic growth, and weak planning systems, gated communities represent a critical way to examine urban inequality and exclusion. By foregrounding expert perspectives and presenting grounded case studies, this article contributes to ongoing debates on how to create more inclusive, connected, and resilient urban environments in the region.