Abstract

Evidence on urban governance has expanded but is fragmented and inadequate. It fails to articulate the complexity of urban governance in a way that would facilitate effective urban transitions. Using a conceptual-cognitive lens, this article describes a method to move away from governance solutions based on functional silos to those based on multidimensional, sustainable systems. Based on a combination of concepts from public policy, governance, public administration, and urban service management, it frames the problem of urban governance as a comprehensive conceptual-cognitive map of the domain. The study validates the framework through expert feedback and the mapping of the literature on urban governance in India between 2018 and 2020. The monad map and theme map emphasise the ontology’s applicability as a methodological tool for evidence generation. The analysis reveals a need to reconfigure urban governance pathways to work towards a sustainable future. The article concludes by offering new conceptual constructs of governance pathways to enhance the policies and practices that shape such transitions.

1. Introduction

Urban governance is central to the notion of equitable and sustainable urban development. With urbanisation projected to grow at a rapid pace, with an addition of 2.5 billion urban dwellers between 2018 and 2050 [1], new modes of governance are sought to address its complex problems [2,3]. Urban governance is traditionally defined as the sum of the many ways individuals and institutions, public and private, plan and manage the common affairs of the city [4,5]. It includes formal institutions as well as informal arrangements [6,7,8]. It highlights the ways in which the government (local, regional, and national) and stakeholders plan, finance, and manage urban areas through a continuous process of negotiation and contestation to allocate social resources, material resources, and political power [9].

The recent literature has explored some of the key concepts, trends, and approaches in contemporary urban governance. The field has expanded, incorporating explanations and analyses of the regulation and decision-making processes for urban issues in various geographical and sociopolitical circumstances [10]. For instance, the literature on the role of urban governance in providing basic urban services in developing countries has focused on its multidimensionality and hybrid governance arrangements [11]. It has examined how actors and interests set agendas, define problems and offer solutions, set goals and regulations, seek legitimacy, represent interests, define citizenship, and address existential challenges like environmental crises [12,13,14,15,16]. This wide range of research on urban governance demonstrates the complexity and divergence of the field.

However, there is a wide gap between the academic research focus and urban development realities. Current research often fails to focus on the real challenges and priorities of city administrators and practitioners [10,17,18]. We need to conduct more research on innovative methods to organise the intricate realities of cities [19] and develop a comprehensive model of the interactions between various sustainable and equitable environmental plans for cities across various time and space scales [20]. The twin goals of ‘administration’ and ‘democracy’, for instance, need to be seen through a systemic lens to examine multi-level government negotiation and city diplomacy [17]. We need to decipher urban governance both analytically and cartographically [21,22,23], and a comprehensive and systemic perspective can reveal co-benefits and synergies [24]. Not surprisingly, scholars are demanding new concepts and terminology to aid in deciphering the multiplicity of urban experiences [10,21]. This would provide a more holistic yet differentiated and systematic view of urban governance across various contexts and countries.

In this paper, we advance the conceptual and methodological foundations for the development of an innovative urban governance framework that represents the complexity and multidimensionality of urban governance. We develop the ontology of urban governance as an abstract conceptualisation to systematise the description of a complex urban governance system. Terminologies and taxonomies organise the ontology, which is defined as a cognitive frame that systematically describes a complex system [25]. The ontology aids in visualizing the urban governance system and its systematic pathways in structured natural English, allowing for the retrospective mapping and assessment of current research in the domain, as well as the prospective construction of a roadmap to guide research, policy, and practice.

We have used ontological frameworks to review smart city research, health, and e-governance services, and they are advantageous in evidence-informed agenda setting for domain-specific or problem-specific changes. We use the ontology to visualise the segmentation and selectivity of academic research on urban governance in India, identify the blind spots in governance concepts, and chart roadmaps for short-term, scalable interventions with a vision for long-term change. Ontological analysis is advantageous to bibliometric analysis for this purpose. Bibliometric analysis looks at the whole field of academic research [26], including the current state of research, future directions, and growth patterns of certain topics [23,27,28]. Ontological meta-analyses, on the other hand, deal with the problem’s complexity to ensure that solutions work. The ontology, as a method, helps to visualise the system’s complexity and reveal the gaps between reality and research in the domain. Knowing the gaps enables one to develop roadmaps for setting the agenda for research, policy, and practice in urban governance. Hence, ontological meta-analysis highlights both the studied and unstudied aspects, whereas bibliometric analysis only reveals the studied aspects.

We validated the framework through expert feedback and the mapping of the literature on urban governance in India between 2018 and 2020. The monad map and theme map highlight the applicability of the ontology as a methodological tool for evidence generation. Building on the results of the validation, we (a) demonstrate governance strategies enumerated as dimensions, elements, and pathways in the ontology; (b) highlight the biases and gaps in academic research presented as monad and themes map; and (c) discuss reform strategies in the light of India’s Smart City Programme.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 delves into the methodological aspects of the research, including the construction and validation processes through ontology development, bibliographic analysis, and cognitive mapping. Section 3 presents the research results and analysis, showcasing the ontology, the bibliographic analysis of scientific literature, and the integration of the scientific literature with the ontology. Finally, Section 4 explores the development of new conceptual constructs to guide future research and policy on urban transition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Ontology

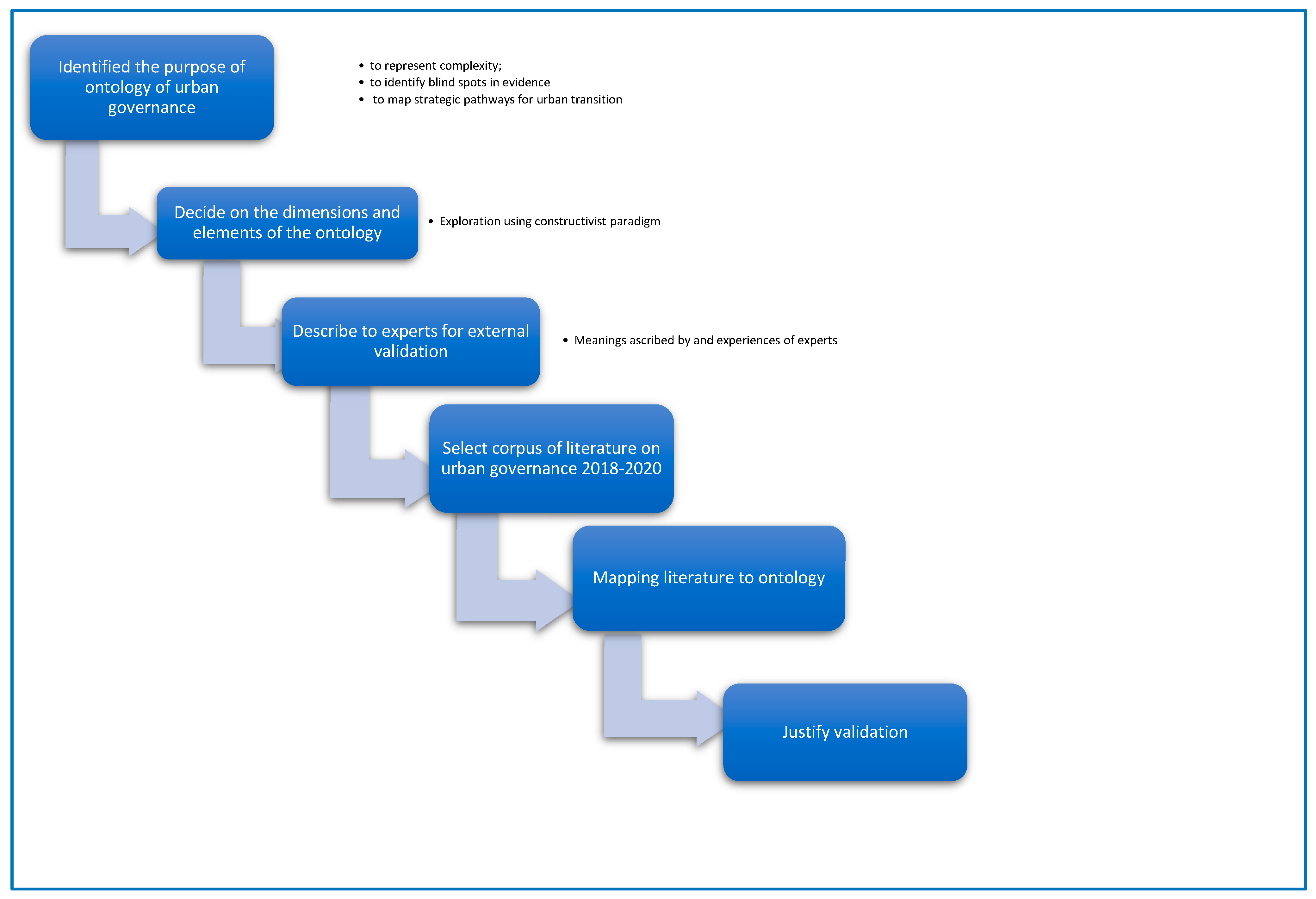

We developed the ontology of urban governance (Figure 1) as a structured, natural-English formulation of the problem. The ontology is created using the methodology outlined by Ramaprasad and Syn [25]. An ontology encapsulates the terminologies, taxonomies, and core logic of a problem [29]. It is a specification of the shared conceptualisation, “the relevant informal knowledge one can extract and generalize from experience and observation” [30], and is used to systematise our description of a complex system [31]. It is a systematic and systemic framework [32] for studying a problem; it is a cognitive map of it. We developed the ontology in three phases. Appendix A provides a diagrammatic representation of the three phases.

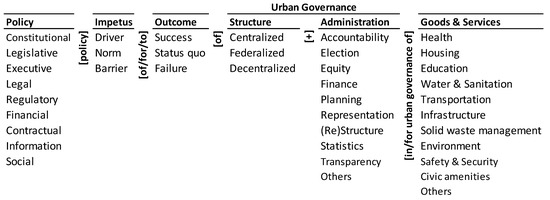

Figure 1.

Ontology of urban governance.

2.1.1. Phase I: Identification of Dimensions and Elements

In the first phase, the dimensions and elements of the ontology were systematically synthesised from the taxonomies and terminologies linked to disciplines such as public policy and public administration, and from the domains of governance and urban service management. The selection of dimensions and elements was based on their applicability to urban service delivery. Two of the paper’s three authors are students of urban governance, and they incorporated their domain expertise into the development of the ontology. Each phase of the ontology’s development was iterative; each cycle involved many attempts until a consensus on the reasoning was reached among the team members. The team decided which items to include, omit, combine (if they were synonyms), subordinate (if they were hyponyms), and superordinate (if they were hypernyms) during each iteration. The current ontology represents the consensus of the collaboration. The main dimensions in the cognitive framing of the domain were identified as Policy, Impetus, Outcome, Structure, Administration, and Goods and Services.

The object of urban governance is the delivery of public Goods and Services and the taxonomy was derived from the UN-Habitat’s Country Activities Report-2019 [33]. The elements of Administration, critical for the effective delivery of Goods and Services, were derived from India’s Second Administrative Commission Report on Local Governance 2009 [34] and World Public Sector Report 2015 [35]. The core aspect of urban governance is the Structure of power sharing in the political system, which influences the Administration and delivery of Goods and Services. The taxonomy is based on the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals, 2017 [34], and Europe’s approach to implementing the Sustainable Development Goals: good practices and the way forward [36].

With problems of urban inequality, sustainability, and safety that are both multi-scalar and geographical in nature, there are implications for urban governance instruments and their local implementation and impacts [37]. Policy Instruments provide necessary directives for effective governance and the typology is derived from the public policy literature [38]. The Impetus of these instruments may be as drivers, norms, and barriers, while Outcomes may be success, status quo, or failure.

2.1.2. Phase 2: Validation of the Ontology: Logic, Expertise, and Experience

The ontology made sense ‘on its face’ to the authors who engaged in coding the literature, so its face validation is high. The authors expressed the components of the ontology in natural English sentences, and the coding of these sentences, as illustrated below, demonstrates its high semantic validity. Furthermore, the dimensions and elements of the ontological framework were derived systematically from the government, international organisations, and public policy literature on urban governance, so its systemic validity is high.

We further validated the dimensions and elements of the ontology based on a roundtable discussion with multiple experts actively working in the field of urban governance [39], including subject experts, bureaucrats, researchers, academicians, civil society members, and urban development practitioners. The purpose of the discussion was to gather feedback from stakeholders on urban governance issues and provide recommendations on the most important areas and methods for establishing effective and efficient urban governance structures, as well as improve coordination among various administrative functions. The participants’ experience and expertise largely drove the discussion.

The dimensions and elements were used to frame and anchor a discussion on the challenges of identifying and achieving an optimal level of Structure for the delivery of Goods and Services to urban centres. Almost all the collaborators were new to this method of visualizing the problem’s core logic using structured language to represent dimensions and elements. During the discussion, they understood and assimilated it. The discussion was systematically mapped to illustrate the spread and scattering of the elements of significance. At the time of the consensus, they perceived the logic of urban governance and the conceptual pathways encompassing the dimensions in the ontology to be isomorphic.

Therefore, the ontology of urban governance has high external validity; the dimensions and elements are not external to the domain of urban governance. The approach for mapping the current state of the research on urban governance in India onto the ontology is described in the next section.

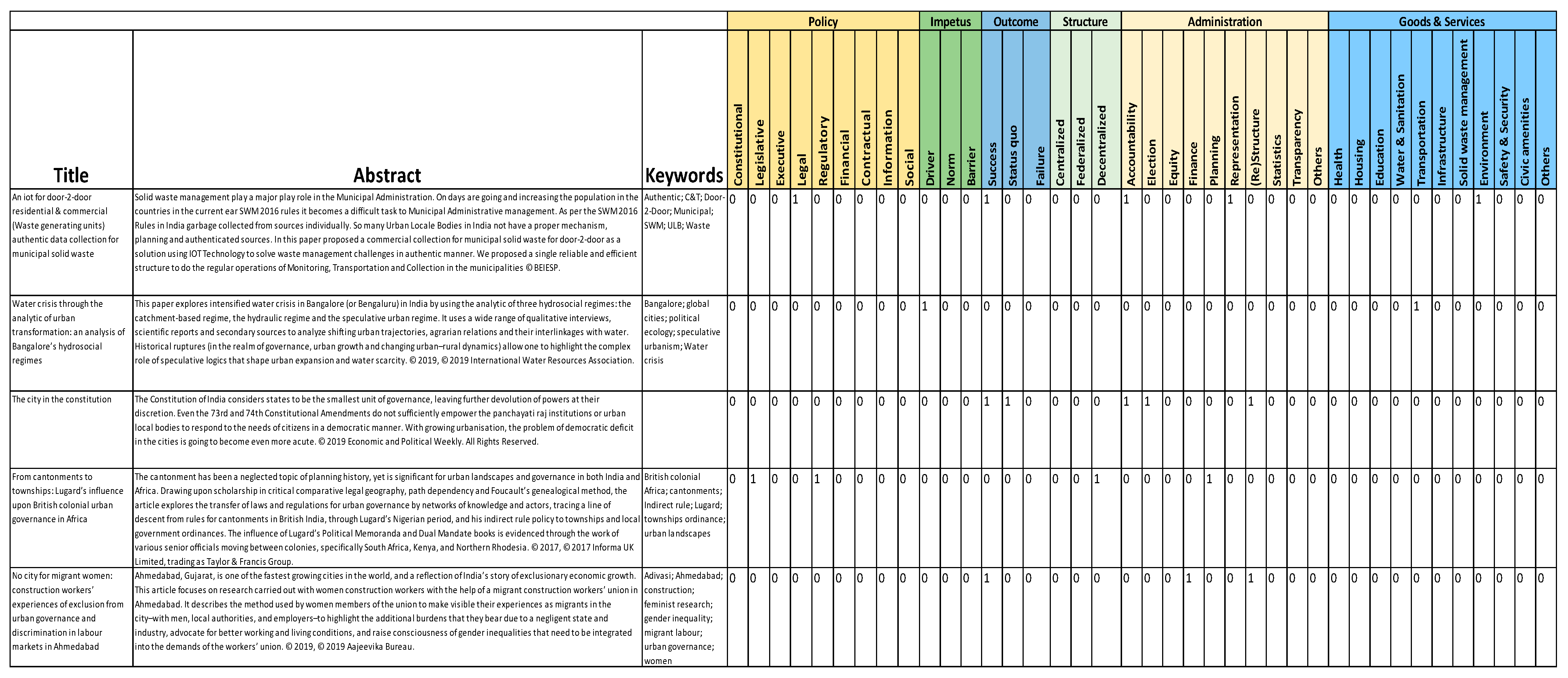

2.1.3. Phase 3: Validation of the Ontology—Research Evidence

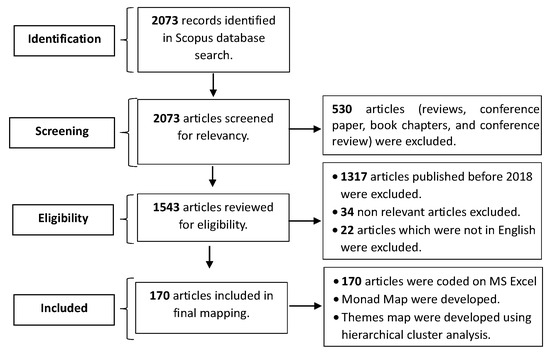

In this phase, all the research articles published on urban governance in India between 2017 and 2020 were mapped onto the framework by the authors and two others through consensus coding using an MS Excel tool. A search of Scopus using the search string ‘TITLE-ABS-KEY ((Governance OR Administration) AND Urban AND India)’ in January 2020 yielded 2073 articles. After excluding (a) 530 reviews, conference papers, book chapters, and conference reviews; (b) 22 non-English articles; (c) 1317 articles published before 2018; and (d) 34 non-relevant articles, the corpus was reduced to 170 journal articles. We mapped the 170 articles onto the ontology. The process is described using the PRISMA [40] statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses as shown in Figure 2. We transported all records to the reference management software, Zotero (Version: 6.0.3.6).

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram of urban governance corpus.

The coding was carried out during a face-to-face conference. The authors and coders simultaneously (a) reviewed the title, abstract, and keywords of each article; (b) discussed the ontology elements it would map to; (c) reconciled the differences; and (d) finalised by consensus to ensure the reliability of coding. A glossary of definitions of the ontology elements was used to assure the validity of the coding. The coding was binary regarding whether the ontological element (or its synonym) was present (1).or absent (blank or 0) in the title, abstract, and keywords of the article. An article was the unit of coding. One could code an article to either (a) one or more elements within a dimension or (b) to one or more dimensions. The coding was not weighted: each article and each element were assigned equal weight. Multiple occurrences of an element in an article were coded only once. A section of the codesheet is provided in Appendix B.

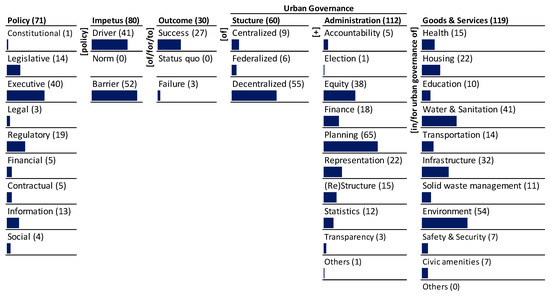

The monad map (Figure 3) summarises, numerically and visually, the frequency of occurrence of each dimension and element of the ontology in the population of articles. The number adjacent to the dimension name and element indicates the frequency. The bar below each element is scaled to the maximum frequency of all the elements. The sum of the frequencies of occurrence of elements in a dimension may surpass the frequency of occurrence of the dimension to which the elements belong, because an article might be coded for several elements of a dimension. For example, in Structure (column 4), where the frequency is 60, the decentralised elements appear in 55 articles, the centralised elements in 5, and the federalised elements in 6.

Figure 3.

Monad map of urban governance in India.

Structure (60) < centralized (9) + federalized (6) +decentralized (55).

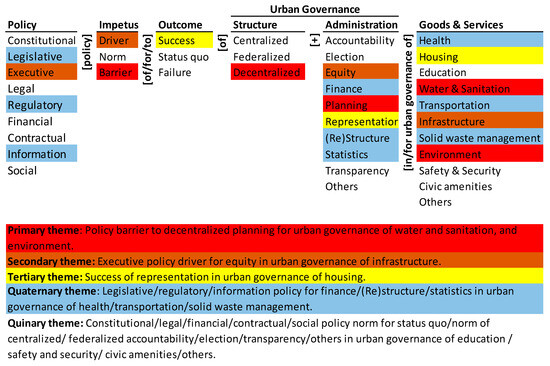

To derive the theme map, hierarchical cluster analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, IBM: Chicago, IL, USA) with a simple matching coefficient (SMC) as the distance measure and the nearest neighbour agglomeration procedure. SMC considers both presence (coded “1”) and absence (coded “0”) elements equally. Syn and Ramaprasad [41] and La Paz et al. [42] provide a detailed justification for the clustering method selection and presentation of the results. The five themes correspond to the agglomeration’s dendrogram’s five equidistant groupings. The themes are illustrated by horizontal and vertical colour bands (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Theme map of urban governance in India.

3. Results

3.1. The Ontology of Urban Governance

We developed the ontology of urban governance as shown in Figure 1, as described above. It deconstructs the domain’s complexity hierarchically and defines it by dimensions, elements, and boundaries. The 10 Goods and Services sectors (listed in the rightmost column) describe a whole range of local provision of Goods and Services to urban residents. It includes health, housing, education, water and sanitation, transportation, infrastructure, solid waste management, environment, safety and security, civic amenities, and others. Administration (second column from right) is critical for effective service delivery; it addresses accountability, election, equity, finance, planning, representation, restructuring, statistics, transparency, and others. The Structure of Administration (third column from the right) may be centralised, federalised, or decentralised. The core aspect of urban governance is the Structure of power sharing in the political system, which influences the Administration and delivery of Goods and Services. The last three columns of the ontology encapsulate the 330 (3 × 10 × 11) potential facets of urban governance. For example, (a) centralised accountability for urban governance of health, (b) federalised planning for the urban governance of the environment, and (c) decentralised representation in urban governance of safety and security.

With problems of urban inequality, sustainability, and safety that are both multi-scalar and geographical in nature, there are implications for urban governance instruments and their local implementation and impacts [37]. The Policy Instruments (the left most column of the ontology) for improving and strengthening urban governance are constitutional, legislative, executive, legal, regulatory, financial, contractual, informational, and social instruments [38]. The Impetus (second column from the left in the ontology) of these instruments may be drivers, norms, and barriers. Together, there are combinations of 9 × 3 = 27 Policy Instruments that determine the Outcome of the 330 facets of urban governance. The Outcomes (listed in the third column from the left) may be success, status quo, or failure.

The six dimensions of the ontology—Policy, Impetus, Outcome, Structure, Administration, Goods and Services—are arranged left to right with connecting terms to form English sentences that represent the potential pathways for urban governance. Each concatenation of a word/phrase from each column with the connecting words/phrases is a unique descriptor of a governance pathway for urban management and represents a function of the system. As an example, below are three urban governance issues and pathways in India generated by mapping them onto the ontology in their respective order:

- “The fact that most States have, during the 1970s and 80s, created state-wide autonomous organizations and parastatals to carry out even local level functions such as water supply also means that the issue of division of functions between such organizations and the local authorities comes in the way of greater decentralization”.

- “Urban Local Bodies in India depend excessively on property tax for revenue apart from being dependent on the State Governments. Other modes of raising revenue, such as municipal bonds, could be explored by the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP). Municipal Corporations of Pune and Ahmedabad have raised issued municipal bonds to raise funds for some of their projects” [43].

- “Parastatals agencies like the Bangalore Development Authority (BDA) and Bangalore Metropolitan Region Development Authority (BMRDA) perform many municipal functions, including urban planning and regulation of land use, which the city government is constitutionally authorized to carry out” [44].

The above issues, when mapped onto the ontology, highlight the following three pathways of urban governance:

- A legislative policy barrier for the success of decentralised planning and representation in urban governance for water and sanitation;

- A financial policy driver for the success of decentralised finance for urban governance;

- A regulatory policy barrier for the success of decentralised planning for the urban governance of infrastructure.

In total, the ontology encapsulates 27 × 3 × 330 = 26,730 pathways of urban governance.

While some of the combinations we derive may be infeasible or not instantiated, many pathways can be used for research and policy decisions. The framework may be adapted to a context by adding elements, deleting them, refining them, and combining them.

3.2. Selectivity in Research Evidence: Monad Map

The dominant focus of the research articles is on Goods and Services (119) and Administration (112). There is a somewhat moderate focus on Impetus (80), Policy (71), and Structure (60), and much less emphasis on Outcome (30).

Goods and Services (column 6) are researched, covering a wide spectrum of elements, but the focus is uneven. The dominant focus is on the environment (54), water and sanitation (41), and infrastructure (32), with moderate emphasis on housing (22), health (15), transportation (14), solid waste management (11), and education (10). This reflects the assumption that a significant reason for the poor quality of life and daily living conditions in urban areas is poor urban governance. However, there is very little focus on safety and security (7) and civic amenities (7), indicating a lack of attention by urban policy researchers towards social cohesion within cities in India.

Among Administrative elements (column 5), the unevenness has been in the form of a high focus on planning (65), equity (38), representation (22), finance (18), (re)structure (15) and statistics (12). The least emphasis is on accountability (5), transparency (3) election (1), and others (1). There is significant discussion on equity and representation, signifying socio-political diversity as critical for urban governance. This is primarily in the context of researchers’ highlighting the need for social inclusion and political participation in efforts to translate the urban development agenda into action. The need to drive the focus towards establishing the institutions and structures that embody democratic characteristics is often highlighted [45,46]. However, the fact that qualitative aspects of administrative functioning, such as accountability and transparency, received little attention in the past should be addressed in the future.

For the elements under Policy (column 1), researchers have taken note of the government programs such as the smart city initiative, represented in the high number of codes on the executive policies. Hence, the emphasis is on the executive (40), with a secondary focus on regulatory (19), legislative (14), and information (13) policies. Some of the recent literature has focussed on technology and informatics solutions to urban concerns, as well as several references to government-led smart city programmes. However, there is considerably less focus on financial (5), contractual (5), social (4), and constitutional (1) policies. Financial policy research is focussed on taxation structures and resource augmentation of urban local bodies [45,47], while social policy like housing policy is discussed within the critical space [48].

Structure research (column 4) reveals that the element decentralised (55) outnumbers centralised (9) and federalised (6) structures. The research on Impetus (column 2) is biased towards barriers (52). Much less focus is on drivers (4), while norms (0) have not been researched. Outcome is highly skewed towards successes: the successful (27) Outcome (column 3) dominates that of failure (3). There is no research on the status quo (0).

To summarise, the analysis of the monad map presents the uneven, non-systemic focus of the research and indicates the need for better alignment of research in terms of coverage of issues. In terms of the dimensions, the research has been selective towards covering the Goods and Services and Administrative dimensions of the urban governance domain, while relatively missing the emphasis on the dimensions of the Outcome, Policy, and Structure aspects. This skewedness in research can have an impact on the overall effectiveness and impact of the research in informing the practice of the domain. Focusing primarily on the Policy aspect, for example, may neglect the full system’s input components, resulting in incomplete solutions.

3.3. Segmentation in Research Evidence: Theme Map

The ontology-based analysis of research on urban governance reveals the co-occurrence of elements of the ontology in the research papers. This is visually summarised in the theme map (Figure 4) that indicates the thematic segmentation of research. It is based on hierarchical cluster analysis of the elements, using the simple matching coefficient distance measure, and the nearest neighbour agglomeration. The five themes represent the five equidistant clusters in the dendrogram of the agglomeration [41]. Different colours in Figure 4 highlight the elements of the five themes. The themes are listed in order of diminishing research dominance—the primary theme is the most prominent, and the quinary theme denotes nonexistence. The themes are segmented representing a subset of dimensions, selectively highlighting a subset of elements in a dimension, as illustrated by colour bands horizontally and vertically (Figure 4). The five themes are as follows:

The primary theme (in red) is the barrier to decentralised planning in the governance of urban water and sanitation and the environment. It is four-dimensional and two-levelled—it is simple. The primary theme is segmented in that it includes only a short fragment of the many potential pathways of urban governance in the ontology. The other potential pathways may include constitutional, legislative, executive, legal, regulatory, financial, contractual, information, and social policy mechanisms for achieving one or more outcomes.

The secondary theme (in brown) is the executive (Policy) driver (Impetus) for equity (Administration) in the governance of urban infrastructure (Goods and Services). The secondary theme is four-dimensional and one-levelled—it too is simple. It indicates other potential pathways may include Structure in terms of being centralised, federalised, and decentralised, as well as Outcome in terms of success, status-quo, and failure.

The tertiary theme (in yellow) is the success of representation in the governance of urban housing. It is three-dimensional and one-levelled—it too is simple. It excludes the different elements under the Policy dimension, one or more elements under Impetus, and one or more elements under the Structure dimension.

The quaternary theme (in blue) is the role of policy mechanisms (legislative/regulatory/information) in Administration (finance, (re)structure, statistics) for the governance of Goods and Services (health/transportation/solid waste management). The theme is three-dimensional and three-levelled. It includes 27 short segments of many potential pathways in the ontology. The pathways may include different types of Impetus, Outcome, and Structure.

The quinary research theme (no colour) summarises the absence in the research corpus. Constitutional, legal, financial, contractual, and social policies are not part of any theme, although executive policy as a driver is part of the secondary theme. Neither are they associated with the Impetus that affects the Outcome or the other dimensions. Amongst the Impetus, the norm for the Outcome is absent, although the barrier and driver are part of the primary and secondary theme, respectively. Centralised and federalised structures are not part of any theme in the research corpus—there is no systematic distinction between centralised and federalised structures. The theme highlights the exclusion of accountability, election, transparency, and others as part of Administration in urban governance research. The theme highlights the absence of the systematic consideration of the governance of the delivery of Goods and Services in terms of education, safety and security, civic amenities, and others—these remain excluded as well. The quinary theme is six-dimensional (same as the ontology) and many-levelled, and there is a complex, vast, and unresearched domain.

The focus of the research themes is skewed towards just a few dimensions and elements. None of the themes comprehensively cover all the dimensions of the ontology. The three most dominant themes are simple: they are three-dimensional, and one- to two-levelled. The fourth theme encompasses three dimensions and layers; it is slightly complex. The quinary (absent) theme is a vast, complex domain across many dimensions and levels that is yet to be researched. Overall, the research corpus coverage is segmented and not systemic.

While the research covers almost all the dimensions of urban governance, what is required is a focus on the themes constituted by interactions across the dimensions. While there’s a need to align the research symmetrically on dichotomic elements such as finding the right balance between the centralisation and decentralisation discourses, what is even more critical is the focus on themes that are relevant to and address the issues of the state of policy, practice, and technology in urban governance and their interactions.

4. Discussion

The ontology has conceptualised urban governance in a way that associates structural politics with functional administrative concepts within specific political settings. It signifies the critical linkages of administrative elements; research on this new conceptual association is useful for bridging the gap between evidence-informed policy, politics, and practice. As an illustrative example, we discuss governance pathways for (a) water and sanitation; (b) infrastructure; and (c) housing.

4.1. Water and Sanitation

The dominant focus of water and sanitation (Figure 3) comprises barriers to decentralised planning (Figure 4). However, in the context of smart urban governance and 24/7 water supply in Karnataka in southern India, several enablers were noted to serve heterogeneity and scale. Both political and financial decentralisation in urban water supply in Karnataka (a state in India) were promoted through Policy Instruments (Legislative, Executive and Regulatory). The decentralised norms equipped the urban local body to adopt a new governance approach. The enablers of governance not only involved institutional scales but also spatial and technological scales. The administrative heterogeneity in terms of modes of delivery, forms of access, and delivery strategies improved the urban population’s coverage and reach. The urban governance pathway involved new actors—private tankers, social innovators, water supply engineers (representation), an innovative technological system of notifications on water supply to customers (transparency), a novel hybrid approach to water sourcing between ground water and surface water—space (planning), and the installation of water vending machines for those underserved by regular distribution networks (equity). A notable omission, however, was the element of ‘Knowledge’ under Administration for accessing and engaging with local resources. Collaboration on location, weather, appropriate vehicle to deliver water, costs, time, and the understanding of other resources is dynamic, has a large reach, and is a recipe for effective local governance.

Hence, the ‘blind spot’ in evidence on urban water supply is apparent and systematically represented by the ontology. It illustrates the various linkages between sustainable and equitable urban environmental priorities at multiple spatial scales and heterogenous administrations. Conceptual constructs of ‘Decentralised-Representation’ or ‘Decentralised-Transparency-Equity’ provide for a more nuanced understanding of the paradigmatic shifts required in urban governance. Research and evidence development in these pathways will enable scalable, short-term interventions that aim to effect lasting change.

4.2. Infrastructure

Our process of ontological mapping indicated the possibility of conceptually associating two or more outcomes (Goods and Services). India’s executive-driven transportation policy (transportation–executive policy) requires more nuanced research to help influence future infrastructural development plans (infrastructure–regulatory–planning). One of the ‘blind spots’ identified is the role of informal public transport systems in cities and the governance approach to the safety and environmental performance of these modes. Despite its important role in meeting mobility needs that either complement the existing public transport systems or fill the gaps left by existing systems, there are negative externalities of safety, security, environmental pollution, and poor health. There is little information available on the subject to allow city officials to make informed policy or planning decisions about the industry [49]. It is therefore important to regulate (regulatory policy) the scheduling of transport and routing of services (planning) based on data on their involvement in road accidents (statistics), to enable road safety (goods and services, transportation, safety and security).

Similarly, in the case of attaining governance objectives in water and sanitation, there is demand for infrastructure services linked to concepts of urgency, heterogeneity, and scale. Urgency is a matter of aging infrastructure with leaks, breakdowns, and contamination [50], resulting in the water quality reaching the users with high variability. While heterogeneity is evidenced in the diverse distribution of water, the concept of scale is the rate of piped water provision and is critical in areas without operational roadways, access, or drainage ways [51]. Hence, there is no single set of remedies to the problem; rather, the nature of the problem changes with time. It requires a dynamic and multidimensional construct for evidence development. For decentralised infrastructure management in water and sanitation services, therefore, it is critical to conceptually associate the following elements:

- Urgency—vulnerability of users (pricing, usage, alternate sources), finance—equity, and statistics;

- Heterogeneity—quality of piped water (quality, time, quantity, pressure)—planning, and statistics;

- Scale—number of user connections—s.

4.3. Housing

Similarly, analogical reasoning when applied to housing highlights the pathways for setting out the policy priorities in governing housing for informal migrant workers. It addresses issues of rental pricing (finance), fake allotment (transparency), and forced consent by private real estate owners (representation) that are rampant in big cities in India [52]. This is worsened by inequality in urban planning (planning) and the availability of comprehensive data (statistics). Governing migrant rental housing in urban areas will involve rent setting, affordability, and ending systemic inequalities.

- Rent setting—ability to pay (finance, equity);

- Accessibility to credit—affordability (finance, equity);

- Locational issues—reconciling the cost of land and transportation costs (finance, planning);

- Adequate space—(planning, statistics, representation).

To sum up, the ontological pathways provide scope for further investigations of new multidimensional urban reality configurations. They represent the potential for new conceptual constructs in governance to improve policy and practice for sustainable urban transitions.

Policy Implications: The ontology of urban governance structures the research field’s diversity in a way that enables paradigmatic shifts in urban governance policies and practices. Current studies on urban governance in India continue to place a strong emphasis on theories and lines of inquiry based on formal systems, norms, and values, and this is most evident in the format, Structure, and content of national urban policies [53]. Policy tools and guidelines for improving and developing towns and cities as contained in these plans are also limiting for local practitioners. The ontology is an entry point for structuring and integrating the emerging urban transformation policy field in India. It will serve as a framework to identify, explain, and assess the emergence of new urban functions, connections, and policy pathways for sustainability and resilience.

The ontology must be adopted as a systemic local framework; show up in cities’ agendas, programmes, and approaches; and give guidance to practitioners. It will bring in place-based knowledge on the informalities within the governance system to guide the decisions and actions of policymakers along effective pathways, away from ineffective pathways, and for the exploration of innovative pathways. For instance, an information Policy Instrument could be a support for social entrepreneurs like NextDrop working in the field of technology to increase communication channels between valve men, engineers and local residents through an interactive voice response system and mobile messaging. Moreover, a social Policy Instrument might reduce the risk of failure in decentralisation in terms of guarding against inefficiencies of urban local bodies as reflected through user charges and/or gaps in participatory management. Hence, not only will it enable practitioners to experiment with collaborative place-making approaches to integrate local knowledge and strengthen a sense of place and empowerment, but it will also provide for integrative governance system knowledge through feedback and learning.

Limitations: While we have covered the published research on the topic exhaustively, it does not cover the so called ‘grey literature’. This literature includes thinktank working papers, practice guidelines, unpublished research papers, and the like. The lack of curated databases for this literature makes it difficult to incorporate them in a reproducible way. One may, in the future, systematise this literature too and incorporate it into a study. Similarly, as new terms emerge in the domain, we can refine and extend the ontology accordingly. The ontology is modular and hence extensible without invalidating the prior analysis.

5. Conclusions

We illustrated the unique approach of ontological meta-analysis and synthesis. The analysis revealed that despite numerous theories, research, policy interventions, and practice guidelines, most of them fail to accurately conceptualise or explain appropriate patterns of urban governance. Urban governance has a complex structure and processes for achieving desired public policy goals. Our research highlighted the need for a systematic and symmetric conceptualisation of the domain. The monad map and theme map not only showed the different areas of focus for research in urban governance but they also showed the need for cross-dimensional interactions and balance to fully understand and suggest solutions for the multiple problems of urban governance. Thus, the ontology systematically presents the scope for explorations into the inter-dimensional dynamics of urban governance and sets the agenda for future research.

We can generalise the ontology and the analysis method to other geographical areas. They can also be used to study the problem at more micro-levels (for example, state or province, city) or macro-levels (for example, region, union of countries). The terms in the ontology may have to be adapted to the terminology of the geographical domain. Similar studies focusing on different geographical units of analysis can provide (a) comparative and (b) refined insights. These insights will help transfer knowledge across domains for research, policies, and practices. They would be an important platform for feedback and learning—for transferring global knowledge locally and local knowledge globally.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.R., A.C. and S.G.M.; methodology, A.R.; validation, A.R., A.C. and S.G.M.; formal analysis, S.G.M., A.C. and A.R.; writing—original draft preparation S.G.M., A.C. and A.R., writing—review and editing, S.G.M., A.R. and A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anilkumar Munikrishnappa and Nibras K. Thodika for their contribution to the Methods section of the paper. We appreciate their support in the coding of the literature.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–126. Available online: https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789210043144/read (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- McGuirk, P.; Dowling, R.; Maalsen, S.; Baker, T. Urban Governance Innovation and COVID-19. Geogr. Res. 2020, 59, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadzadeh, A.; Fekete, A.; Khazai, B.; Moghadas, M.; Zebardast, E.; Basirat, M.; Kotter, T. Capacitating Urban Governance and Planning Systems to drive Transformative Resilience. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 96, 104637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, T.G. Governance, Good Governance and Global Governance: Conceptual and actual challenges. Third World Quart 2000, 21, 795–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoker, G. Public-Private Partnerships and Urban Governance. In Partnerships in Urban Governance: European and American Experiences, 1st ed.; Pierre, J., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1998; pp. 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brie, M.; Stölting, E. Formal Institutions and Informal Institutional Arrangements. In International Handbook on Informal Governance, 1st ed.; Christiansen, T., Neuhold, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2012; pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, I.; Lowndes, V.; Salazar, Y. Understanding Institutional Dynamics in Participatory Governance. Crit. Policy Stud. 2022, 16, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo-Mieth, A. Examining the Dynamics Between Formal and Informal Institutions in Progressive City Planning. Urban Aff. Rev. 2023, 59, 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avis, W.R. Urban Governance (Topic Guide); GSRDC, University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2016. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5857f644ed915d0aeb0000d6/UrbanGov_GSDRC.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Da Cruz, N.F.; Rode, P.; McQuarrie, M. New Urban Governance: A review of current themes and future priorities. J. Urban Aff. 2019, 41, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartini, N.; Jones, P. Urbanization and Urban Governance in Developing Countries. In Urban Governance and Informal Settlements, 1st ed.; Springer Nature: Switzerland, 2019; pp. 13–40. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-06094-7_2 (accessed on 16 March 2024).

- Minnery, J. Stars and their Supporting Cast: State, market and community as actors in urban governance. Urban Policy Res. 2007, 25, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, F. Understanding Good Urban Governance: Essentials, shifts, and values. Urban Aff. Rev. 2014, 50, 553–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, L. Actors and Shifting Scales of Urban Governance in India. In Handbook of Megacities and Megacity-Regions; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makunde, G.; Muvavarirwa, V.; Chirisa, I. Future of Urban Governance and Citizen Participation. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Futures; Brears, R.C., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, E.H.; Constantino, S.M.; Centeno, M.A.; Elmqvist, T.; Weber, E.U.; Levin, S.A. Governing Sustainable Transformations of Urban Social-ecological-technological Systems. npj Urban Sustain. 2022, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. Transforming Urban Governance Using Research. Decentralization & Localization. 2021. Available online: https://decentralization.net/2021/06/transforming-urban-governance-using-research/ (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Meijer, A.; Bolívar, M.P.R. Governing the Smart City: A review of the literature on smart urban governance. Int. Rev. Admin. Sci. 2016, 82, 392–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baud, I.; Jameson, S.; Peyroux, E.; Scott, D. The Urban Governance Configuration: A conceptual framework for understanding complexity and enhancing transitions to greater sustainability in cities. Geogr. Compass 2021, 15, e12562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineo, H. Towards Healthy Urbanism: Inclusive, equitable and sustainable (THRIVES). Cities Health 2022, 6, 974–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, C.; Karaman, O.; Hanakata, N.C.; Kallenberger, P.; Kockelkorn, A.; Sawyer, L.; Struele, M.; Wong, K.P. Towards A New Vocabulary of Urbanisation Processes: A comparative approach. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 19–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baud, I.; De Wit, J. New Forms of Urban Governance in India: Shifts, Models, Networks and Contestations, 1st ed.; Sage Publishing: New Delhi, India, 2009; p. 416. Available online: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/new-forms-of-urban-governance-in-india/book233781 (accessed on 4 June 2022).

- Liu, W.; Mei, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, W.; Hu, F.; Xu, D. City Brain: A New Model of Urban Governance. In IEIS 2021: Proceedings of 8th International Conference on Industrial Economics System and Industrial Security Engineering; Li, M., Bohács, G., Huang, A., Chang, D., Shang, X., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Surveyer, A.; Elmqvist, T.; Gatzweiler, F.W.; Güneralp, B.; Parnell, S.; Prieur-Richard, A.-H.; Shrivastava, P.; Siri, J.G.; Stafford-Smith, M.; et al. Defining and Advancing a Systems Approach for Sustainable Cities. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 23, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaprasad, A.; Syn, T. Ontological Meta-Analysis and Synthesis. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 37, 138–153. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/cais/vol37/iss1/7/ (accessed on 4 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.N.; Li, D.D.; Robinson, N.; Liu, J.P. Practical guidance on bibliometric analysis and mapping knowledge domains methodology—A summary. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2022, 15, 102203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Chen, Y.; Duan, Y.; Zheng, Y. Urban Governance: A review of intellectual structure and topic evolution. Urban Gov. 2023, 3, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulistyaningsih, T.; Loilatu, M.J.; Roziqin, A. Research Trends on Smart Urban Governance in Asia: A bibliometric analysis. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, T.R. Toward Principles for the Design of Ontologies Used for Knowledge Sharing? Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 1995, 43, 907–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prévot, L.; Huang, C.R.; Calzolari, N.; Gangemi, A.; Lenci, A.; Oltramari, A. Ontology and the lexicon: A multidisciplinary perspective. In Ontology and the Lexicon: A Natural Language Processing Perspective; Gangemi, A., Lenci, A., Oltramari, A., Huang, C., Prevot, L., Calzolari, N., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cimino, J.J. In Defense of the Desiderata. J. Biomed. Inform. 2006, 39, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creed, W.E.D.; Langstraat, J.A.; Scully, M.A. A Picture of the Frame: Frame analysis as technique and as politics. Organ. Res. Methods 2002, 5, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Country Activities Report-2019: Supporting the New Urban Agenda; United Nations Human Settlement Program: Nairobi, Kenya, 2019; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/documents/2019-05/un-habitat_country_activities_report_-_2019_web_0.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Government of India. Voluntary National Review Report on Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals. In The High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development; United Nations High Level Political Forum: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/16693India.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- United Nations. World Public Sector Report 2015: Responsive and Accountable Public Governance; Department of Social and Economic Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://publicadministration.desa.un.org/publications/world-public-sector-report-2015 (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Niestroy, I.; Hege, E.; Dirth, E.; Zondervan, R.; Derr, K. Europe’s Approach to Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals: Good Practices and the Way Forward. Directorate-General for External Policies-Policy Department, European Parliament. 2019. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EXPO_STU(2019)603473 (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Majoor, S.; Schwartz, K. Instruments of Urban Governance. In Geographies of Urban Governance: Advanced Theories, Methods and Practices; Gupta, J., Pfeffer, K., Verrest, H., Ros-Tonen, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascoumes, P.; Gales, P.L. Introduction: Understanding Public Policy through its Instruments—From the Nature of Instruments to the Sociology of Public Policy Instrumentation. Governance 2007, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anilkumar, M.; Chandra, A.; Mitra, S.G.; Ramaprasad, A.; Singai, C.; Thodika, N.K. Urban Governance in India Report; Ramaiah Public Policy Center: Bengaluru, India, 2020; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339499594_Report_on_Ramaiah_Roundtable_on_Urban_Governance_in_India (accessed on 16 August 2020).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19621072/ (accessed on 17 April 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syn, T.; Ramaprasad, A. Megaprojects—Symbolic and Sublime: An ontological review. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2019, 12, 377–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Paz, A.; Merigó, J.M.; Powell, P.; Ramaprasad, A.; Syn, T. Twenty-five years of the Information Systems Journal: A bibliometric and ontological overview. Inf. Syst. J. 2020, 30, 431–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, R. An Analysis of Crime in India’s Largest Urban Agglomerations. Observer Research Foundation. 2019. Available online: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/an-analysis-of-crime-in-indias-largest-urban-agglomerations-57166/ (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Idiculla, M. Governing the city-region: Rethinking urban and regional governance in India. In Future of Cities: Planning, Infrastructure, and Development; Kumar, A., Meshram, D.S., Eds.; Routledge India: London, UK, 2022; pp. 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deSouza, P.R. The Struggle for Local Government: Indian democracy’s new phase. Publius 2003, 33, 99–118. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3331198 (accessed on 4 October 2022). [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, R. Federalism, Urban Decentralisation and Citizen Participation. Econ. Political Wkly. 2007, 42, 674–681. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4419283 (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Rajhans, R.K.; Halder, A. Urban Infrastructure Financing in India: A proposed framework for ULBs. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. 2019, 15, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. The Credibility of Slums: Informal housing and urban governance in India. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 876–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Singh, S.; Ghate, A.T.; Pal, S.; Wilson, S.A. Informal Public Transport Modes in India: A case study of five city regions. IATSS Res. 2016, 39, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumpel, E.; Nelson, K.L. Intermittent Water Supply: Prevalence, practice, and microbial water quality. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devadiga, A. ‘Water when you need it’: Drawing lessons from practices in Hubli-Dharwad, India. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2020, 42, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Gupta, R. The Empty Promise of Migrant Rental Housing. Impact and Policy Research Institute. 2021. Available online: https://www.impriindia.com/insights/migrant-rental-housing-homeless/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Kundu, D. Urbanisation in India: Towards a national urban policy framework and smart cities. In Developing National Urban Policies: Ways forward to Green and Smart Cities; Kundu, D., Sietchiping, R., Kinyanjui, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 89–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).