1. Introduction

The sustainable city, a concept that started in the 1970s as an “eco-city” movement that sought to build cities in balance with nature [

1], is now generally defined as a city that exerts minimal damage on the environment while maintaining a diverse and resilient economy, an equitable distribution of resources, and a means of citizen participation. On all of these fronts—diversity, equity, engagement—small-scale urbanism is thought to have a better alignment with sustainability goals than large-scale urbanism [

2]. Following the work of Jane Jacobs [

3], urbanists have been promulgating the benefits of small-scale urbanism, denouncing the liabilities of large-scale form and arguing that neighborhoods that develop or redevelop on a small scale are the ones that are the most sustainable and resilient [

4]. Large-scale urban developments—“mega-projects” in the form of town centers, university campuses, and other large format urban schemes—are viewed as antithetical to Jane Jacobs’ brand of incremental change, and the very opposite of a resilient and sustainable city [

5,

6].

While scale is an essential factor in discussions about sustainable cities, there is no common understanding of what scale is or how it should be measured. Is it about buildings, lots, and block sizes? Is it about single vs. corporate ownership of land? Is it about the geographical distances between points? Cities are aggregations of all of these elements —small lots with single family homes, 200-acre parcels with multi-use buildings with thousands of square feet, and infrastructure and public spaces ranging from intimate to vast. The variation of the scale of urbanism from small to large creates a multitude of effects and experiences.

This paper is intended to shed some light on the issue of scale by working through examples of how it might be measured and evaluated. For the purposes of this study, which is a quantified analysis of scale, I define scale as a physical condition of the urban environment that can be assessed based on building size and building size per block. Specifically, scale is measured by (1) the size of buildings, including stories and square footage; and (2) the mean and percentage of buildings of different sizes on a block.

I do not propose a definitive nor an inclusive treatment of scale, since the number of possible forms and measures is much larger than a single paper. My goal, instead, is to offer specific examples of how scale, as an essential variable in sustainability debates, might be defined and measured. I do this by attempting to answer a set of questions related to scale: How has scale changed over time? What variables correlate with different urban scales? Are there measurable differences regarding block quality and socio-economic factors that can be linked to the scale of buildings and blocks? My purpose is to offer both a methodological and empirical contribution to the understanding of scale, using the City of Chicago as a case study. In my particular conceptualization, scale is measured on the basis of building type and block size.

The analysis is in three parts. I first look at the site level to investigate scale change over time. I wanted to know what occupied large development projects before they were built, and, using historical Sanborn maps, offer a way to characterize urban scale change over time. Thirty-one sites were selected for historical vs. current comparison, using data on publicly funded major developments constructed over the past several decades. I was able to quantify that the historical urban fabric had five times as many buildings, and a much higher percentage of buildings with mixed use. Despite the larger format of buildings (in terms of footprint and height), the historical urban fabric also had five times the amount of building square footage.

The second part of my analysis involved comparing urban scale to block characteristics like pedestrian quality. I wanted to know whether there is a quantifiable difference between large- and small-scale urbanism in terms of objective measures of urban quality. This required devising (1) a typology of urban scale and (2) a block rating system. I first compared the block characteristics of the 31 mega-development project sites to the block characteristics of their surroundings. I then compared block characteristics and scale for the city as a whole. I found that, in the City of Chicago, small-scale urbanism is associated with higher pedestrian quality.

For the third part of the analysis, I correlate scale and socio-economic characteristics at the census tract level. The results illuminate a mixed set of differences between scale and socio-economic characteristics like income and housing value.

Knowing how to approach the issue of scale is a fundamental dimension of urban analysis, perhaps as important as understanding how to measure population decline or revenue gain. The research presented here is a methodological and empirical contribution that applies a specific approach to scale definition, measurement, and analysis. I offer a delineation of scale ranging from “small” to “large”, propose a method of measurement, and then apply several techniques to examine how scales of urban development have evolved and what their associated characteristics are.

2. Literature Review

Cities have long developed at multiple scales simultaneously, for different purposes and with different effects. Large-scale development was an expression of political power, of absolutism, or of the centralizing force of an authoritarian regime. Monumental scale is a natural fit for authority and control, presupposing an “unentangled decision-making process” and expressing that the ruling authority has the necessary power to get things done [

7] (p. 217). Alongside this larger scale, small-scale urban fabric was created and recreated by individual owners, developers of various sizes, and builders working in a more incremental manner. Urban change was accomplished lot by lot, block by block, through the work of many individual owners rather than despots, governments, or large developers [

8].

A few important studies have attempted to document these scale changes. Warner and Whittemore [

8] chart the evolution of an imagined U.S. city amalgamized from Boston, Philadelphia, and New York. They describe how, through the mid-18th century, most dwellings were small in part due to the high costs of construction. Even in the early streetcar era of massive rowhouse neighborhood expansion, most were built by craftsman at a rate of three to six per year, yet a homogeneity of style tended to develop outside of legal regulation. Hunter categorizes homes into three types: freestanding, attached, and apartments, and charts their evolution as forms in the American landscape [

9]. Scheer expands this typology to include not just non-residential buildings, but also patterns of land subdivision, and emphasizes how historical patterns may constrain redevelopment possibilities [

10].

Beyond historical analysis, the literature on scale has focused on debating the pros and cons of different scales. Debates about the effect of scale go back at least to the foundations of the field of planning, particularly in the U.S., when Daniel Burnham’s famously declared “make no little plans, for they fail to stir the hearts of men” [

11]. Proponents of large development argue that this is the scale at which jobs are generated, infrastructure is financed, and city revenues are increased. The impulse to “go big” in city planning was further promulgated by modernist concepts of urbanism promoted through planners and architects associated with the Congres Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne, known as CIAM [

12]. The large scale of modernist towers and freeway schemes prompted Jane Jacobs, among others, to castigate planners [

3]. Mid-twentieth century urban renewal (

Figure 1) was done at a large scale around the globe, and resulted in widespread displacement. In the U.S., large-scale urban renewal was often directed at African-Americans, prompting further debate about the issue of scale. Relatedly, Jacobs included the scale of finance in her critique, praising the benefits of “gradual money” over the deleterious effects of the “cataclysmic money” inherent in most large plans [

3] (p. 291–317). These debates evolved into the 1970s economics of “Small is Beautiful” [

13] and calls for informal incremental development as a solution to housing in the developing world [

14].

In the 1980s and 1990s, scale debates pinned urban-minded preservationists as small-scale revitalizers working against status quo over-sized suburban sprawl and large “public−private” development schemes [

15,

16]. As the preservationists worked to revitalize disinvested urban areas, others called for zoning reform to allow small, multi-unit buildings [

17,

18]. Urban designers [

19,

20,

21,

22] argued that small-scale urbanism was not only more visually appealing and experientially rewarding, but it was better able to support diverse economic and social activity. The New Urbanist movement pitched itself as a champion of small-scale urbanism battling large-scale development that they regarded as an enabler of car-based urban form [

23].

While the benefits of small-scale—and the negative impact of large-scale—urbanism were widely recognized by the end of the 20th century, large-scale urbanism continued. This was partly a consequence of boosterish claims about the return of central cities [

24,

25,

26,

27], which stimulated larger-scale private investment in inner-city sites, often enticed by municipal subsidies [

28]. Some cities, such as Vancouver, B.C., attempted to infuse urban placemaking principles in these new large-scale developments [

29]. Yet the large scale—in both physical form and in terms of the aggregation of finance and capital—was critiqued for contributing to an affordability crisis [

30,

31] and for creating a global homogenized urban aesthetic irrespective of local conditions [

32]. Projects often ran over budget and failed to provide the affordable housing and municipal revenue proponents had claimed [

33,

34].

The term “mega-project” entered the lexicon as a descriptor of the expanding scale of city building. Flyvbjerg, Bruzelius, and Rothengatter [

35] loosely define mega-projects as those over USD 1 billion in costs with a focus on infrastructure. Fainstein and others define mega-projects as “very big, mixed-use developments [that cities use] as attractors of multinational business and sites for new housing,” [

32] (p. 768); see also [

36,

37]. These projects are often built on obsolete or under-utilized industrial land, a distinction from the residential displacement associated with mid-twentieth century urban renewal [

38].

There is a perception that these recent mega-projects are “lacking the layering of old and new, small and big, that gives central cities their ambiance and opportunities”, [

32] (p. 783), and urbanists have turned their attention to the benefits of “human-scale”—which is mostly “small-scale”—development. Research on urban morphogenesis (the processes that shape the physical form of cities over time) and urban morphology (patterns, typologies, and configurations of urban form) ties into these interests because scale is a significant aspect of the analytical approach. For example, Hillier and Hanson [

39] analyzed spatial configuration, including pattern and scale, to understand the relationship between form and function. Busquets [

40] examined Barcelona’s urban morphology to understand how it contributes to a human-scale environment. Research on cities like Copenhagen, Amsterdam, and Paris have explored the successful implementation of policies and design strategies that enhance human-scale qualities and promote active modes of transportation, which often translates to what would be considered “small-scale” urbanism [

41,

42]. Jan Gehl [

43] studied the relationship between urban design and human behavior, emphasizing the importance of creating pedestrian-friendly environments and human-scale interventions aimed at increasing social interaction, healthier lifestyles, and improved overall urban livability.

Appreciation of small-scale urban form has translated to practice in several ways. Some focus on temporary and smaller-than-a-building scale “Tactical” or Do-It-Yourself (DIY) interventions [

2,

44]. Others looks for ways to encourage and support small-scale development through developer trainings and networks, such as the Incremental Development Alliance (incrementaldevelopment.org) or through advocacy, research, and consultancy (smalldevelopmentcounts.org; recastcity.com). These advocates argue that the current development milieu accommodates single-family detached housing and larger buildings over four stories, but thwarts “Missing Middle” smaller-scale development that falls in between [

17,

45]. There has been some focus on the regulatory and financial barriers small-scale urbanism endures [

5]. Others have focused on the integrated role small-scale manufacturing can play toward revitalization [

46]; see also [

47].

Another theme advanced by proponents is the greater affordability and thereby equity that could be achieved through increasing the housing supply with small-scale development. Relatedly, proponents tout small, incremental development [

4] and small-scale main street businesses [

48] with integrated manufacturing [

46] as tools towards building more vibrant, equitable communities. This small-scale urbanism is often positioned, both implicitly and explicitly, as either a more equitable alternative to large-scale capital and subsidy-intensive mega-projects, or a neglected co-contributor to urban vitality. Critics from the left point to the racialized social construction of housing values that would nevertheless persist [

49]; for a response to the critique, see [

50]. There are also critiques of incremental urbanism for its inability to redress inequities [

51,

52]. Large-scale social housing, if done right, is still not ruled out as an appropriate scale at which to solve the affordability crisis [

53,

54,

55].

These large-scale private developments are often subsidized. In the U.S., this is done through Tax Increment Financing (TIF), a financing tool that allows administrators to pay for programs with future tax revenues generated within a TIF district (an area that has demonstrated “blight” conditions). The property taxes from the TIF district are fixed for a certain period of time (often 20 years), and tax growth above the fixed base level is diverted away from general revenue capture toward a separate TIF district fund (the difference in revenue is the tax increment). The subsidies are justified as necessary to both attract investment to desired areas and mobilize the large amounts of capital required for public infrastructure and amenities. Proponents claim that these subsidized, large-scale developments create jobs, tax revenues, and infrastructure investments that could never be generated in an incremental fashion. U.S. city governments are much more focused on subsidizing large-scale private developments in the name of revitalization, justified as necessary for mobilizing the large amounts of capital needed for public infrastructure and amenities.

But critics argue that TIFs and the mega-scale they tend to be associated with are a form of corporate subsidy, used as a cost-free instrument to secure deals with corporations, frequently in areas that do not need supplementary public support [

56]. Common examples of TIF use in Chicago include the subsidization of corporate headquarter relocation or renovation, the provision of general support and monetary incentives for private companies, and upscale development in and around the economically advantaged downtown area (the “Loop”). For example, United Airlines received USD 31 million to relocate to downtown Chicago, CNA received USD 13.7 million to renovate its headquarters, and Carbide and Carbon received USD 8.5 million to renovate the Hard Rock Hotel [

57]. While not a TIF specifically, the outcry against and eventual rejection of New York City’s bid for Amazon’s H2Q suggest that public and professional opinion on the efficacy of government-subsidized mega-projects as a planning strategy may be shifting [

58].

This brief literature review, covering the history and pros and cons of small-scale and incremental projects vs. mega-projects, tends to focus on individual cases, or cases of a similar sub-type, such as transportation infrastructure. My research proposes and then tests a methodology to analyze the urban fabric at a range of scales. My goal is to better understand scale change and how it might be measured and evaluated.

4. Results

4.1. Historical Analysis

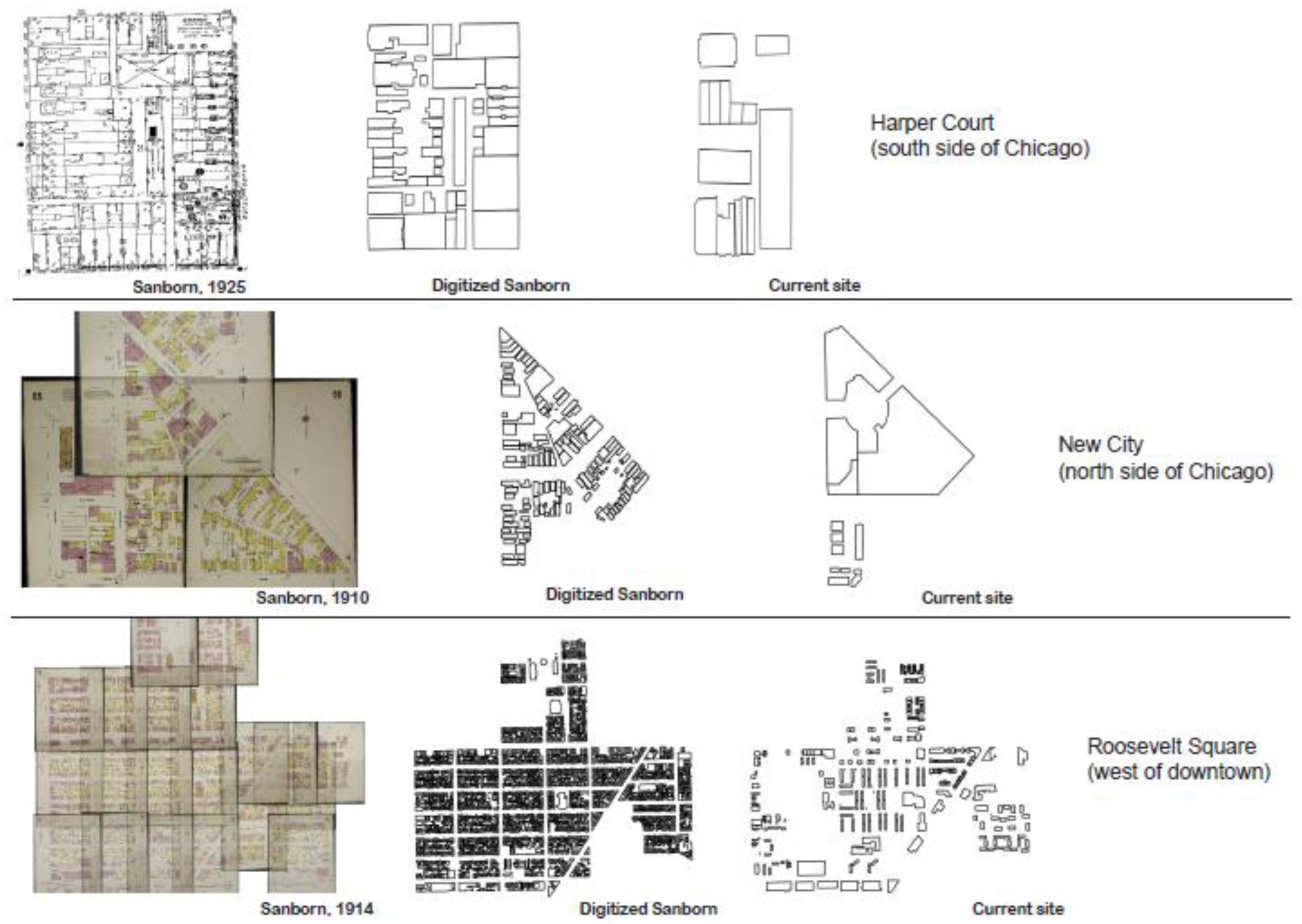

Figure 7 shows three comparisons between historical and contemporary urban scales for a selection of my 31 sites. As expected, the figures show a rather stark kind of urban change, from multiple small buildings (likely with many individual owners) to large footprint buildings under more consolidated ownership. The texture of urbanism is radically different. The smaller buildings likely created a street vibrancy as a result of diverse uses and façade treatments, and individually articulated building types with variation in heights (albeit all in small format). Smaller scale often correlates with a closer relationship between public and private space, with windows and doorways connected more directly to the public realm of the sidewalk. Although it is important not to sentimentalize the vitality that the maps and images of the older, smaller fabric suggest—as there was likely a higher degree of disorder, inequity, and possibly blight—it is difficult not to imagine a higher degree of vibrancy and life emanating from storefronts, residences, and small factories. Buildings, uses, and people shared a public realm that was closely integrated—or at least more so than what is suggested by the standard design and programming of many large-format buildings in the U.S.—by virtue of these smaller scales.

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 quantify these impressions.

Table 3 is a comparison of the number of buildings and housing units and the average and total square footage of the historical urban fabric (“Sanborns”) and the current development pattern. There are almost five times as many buildings on the historical sites, which supports the impression that these areas likely contained a much more vibrant mix of people and activities. Average building square footage was much smaller, as expected; less than a tenth the size of the average building within the currently existing sites. The table also shows that the total square footage was much greater historically, almost 25 million square feet of building space on the Sanborns as opposed to 5.6 million in the current sites.

Interestingly, the number of housing units is similar comparing the two time periods, with the current sites showing slightly more housing units than Sanborns. Thus, the argument that large scale development is needed to increase the housing supply does not really hold—at least not using my sample of sites. Alternatively, given the extreme decrease in total square footage mentioned above, one could argue that the new developments writ large never attempted to increase the housing supply, despite the abundance of developable area. The current units are also contained in much fewer buildings and in the form of apartments.

Table 4 quantifies this difference. The Sanborn sites were made up of buildings that were one or two stories, with only 19% in the 3–4 story range and only 1% above four stories. These units consisted of housing over stores, single-family houses, and small apartment buildings. The contemporary situation has most buildings in the 3–4 range, and 14% with more than 4 stories.

Table 5 gives details on the range and types of uses for the two time periods. Uses on the historic sites were much more varied. About 18% of the buildings had mixed uses within the same building, mostly a mix of commercial and residential. The large format sites are predominantly residential or commercial, with only 2% mixed use.

4.2. Block-Level Analysis

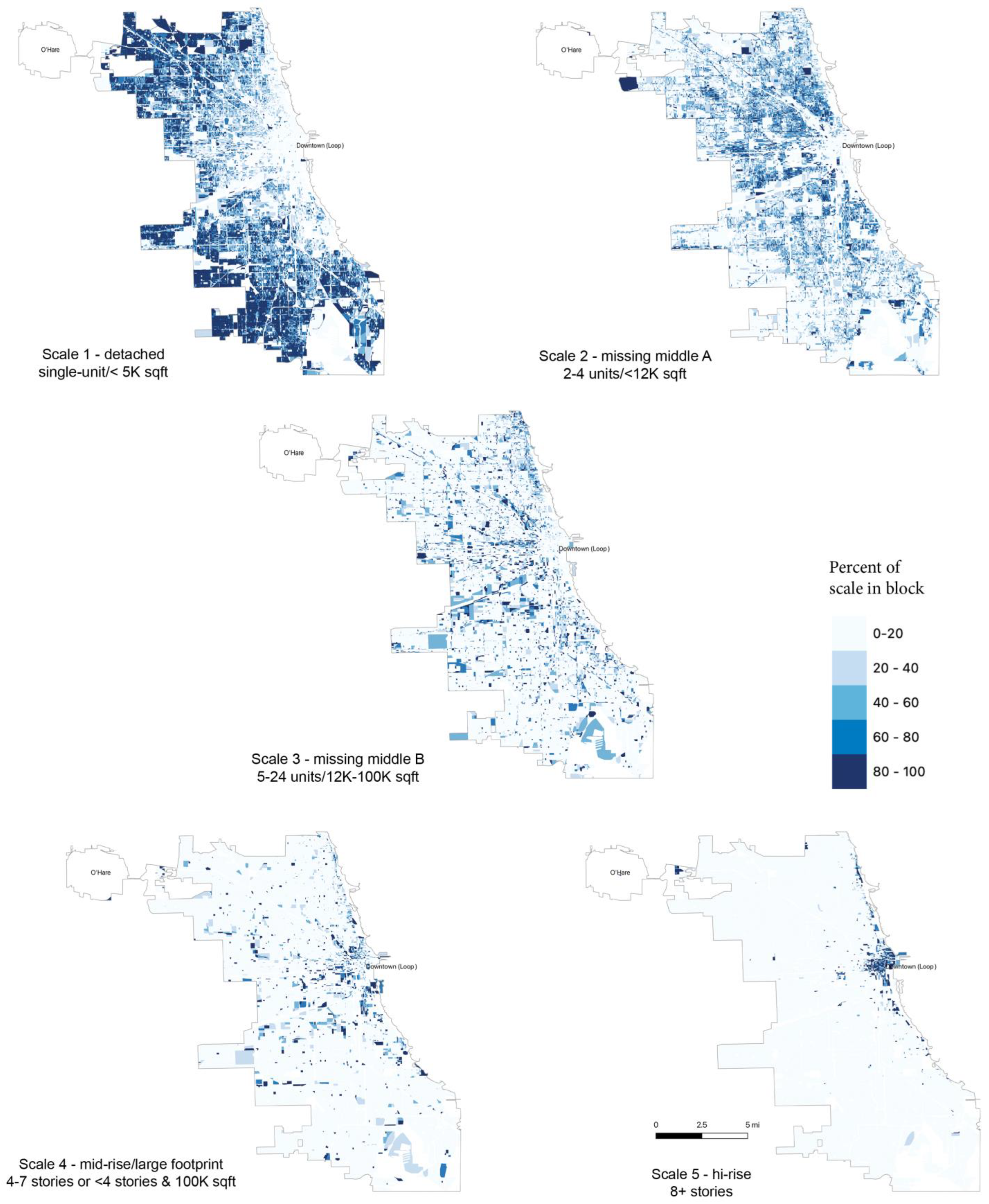

Figure 8 shows the spatial distribution of each scale type. Each map shows the percentage of buildings of a particular scale in a block. Scale 1 is capturing single-family housing and other detached, smaller buildings (under 5000 square feet), and the distribution is predictably in the outer suburban locations of Chicago. There is very little of this scale in the downtown (“Loop”) or inner ring of the city. The blocks with higher percentages of “missing middle” housing, scales 2 and 3, are quite even distributed throughout the city, although scale 2 buildings are slightly more prominent on the north side (which is wealthier and whiter). Scale 4 buildings are more clustered and scale 5 buildings are mostly confined to the downtown area. Thus scale, at least in Chicago, is following a somewhat predictable pattern for the low and high ends of the scale, but is variegated for the middle scales.

Table 6 compares scale and BlockScores for four groups: blocks with mega-developments, blocks immediately around them, blocks with commercial uses (excluding the first two sets of blocks), and all other blocks. Score percentages are not markedly different, although the BlockScore with the highest percentage for mega-development blocks is “0”, whereas for all other categories it is “1”.

Table 7 summarizes ANOVA regression results in which BlockScore and block scale are compared for the city as a whole—not just for my 31 mega-development sites. Each score dimension was converted to a dummy variable. For example, if a block had a minimum score of 1 for the “Mixed Use” dimension, it received a “1”; if a block had a minimum score of 1 for “Daily life uses,” it received a “1”, etc.

The results show that mixed use, degrading factors, and daily life uses share the same associations; all are positively associated with larger building scales (i.e., mean building square footage is higher). For the three dimensions, all scales are positively correlated except building scale 1. This is perhaps not a surprising result for daily life and mixed use, which by my stringent definition (for mixed use, a minimum of two daily life uses plus one other non-residential use on the block) is unlikely to be associated with small footprint buildings, most of which are single-family dwellings. What is more surprising is that daily life and mixed use are not the sole domain of large buildings but are also correlated with all scales except scale 1. Degrading factors are also higher for all building scales except scale 1.

One variation that the table shows is that block character is higher for scale 2 buildings—missing middle housing in the form of 2–4 unit structures, less than 4 stories. Overall, the higher the block character score the lower the mean building square footage, but this is not driven by scale 1 buildings—it is only associated with scale 2 buildings. High block character is significantly correlated with lower percent scale 1 and percent scale 3 buildings (the larger “missing middle” category). There was no association, higher or lower, with larger-scale buildings.

4.3. Tract-Level Analysis

Table 8 is a summary of tract-level regression results, where I regressed the mean building square footage and percent of each scale type (within a tract) on socio-economic variables. The table reports only significant results (

p ≤ 0.001, and an R-square > 0.1). Population density has an inverse relationship with mean building square footage in a block, although it is positively associated with all scale percentages. This is a provocative finding, as it signals the importance of context and net density calculation at the tract level. It could signify that lower-scale buildings might actually have the same density level as larger-scale buildings, depending on site (tract) coverage. It also shows that scale 1 percentage (single family detached) is a strong predictor of density: when the regression is run with scale 1 included and one of the other scales omitted (to avoid multi-collinearity), mean building square footage and scale 1 are strongly and negatively associated, and all other scales lose significance.

Again scale 2—the lower end of missing middle housing—has some interesting associations. It is a significant variable in every case, and the only variable with significance for median housing value. Thus, buildings in the 2–4 unit range, or under 12,000 square feet, have a positive linear association with income, housing value, percent rental, unit type diversity, and percent older housing (building before 1939). The picture that emerges is that scale 2 with its dense, historic, unit diverse, and smaller scaled texture is also the scale that emerges as higher income and higher valued—the classic walkable, gentrified neighborhoods of Chicago’s north side.

The largest scale—scale 5—also has some interesting associations. Like scale 2, scale 5 has a positive linear association with density and median income, and a negative association with percent living in same house in previous year. However, unlike scale 2, the association with unit type diversity is negative, perhaps showing that larger-scale contexts tend to be more monolithic. In addition, unlike scale 2, there is no association with median value, percent rental, income diversity, or building age.

In sum, the first method (historical analysis) showed that small-scale urbanism had five times the amount of building square footage and a much higher percentage of buildings with mixed use, as compared to the current, larger building scale. The second method (block analysis) showed that small-scale urbanism is associated with higher pedestrian quality. The third method (tract analysis) showed that smaller-scale urbanism is associated with higher income, higher housing value, and unit type diversity, while the largest scale had a positive association with income but a negative association with unit type diversity.

5. Conclusions

Having a firm grasp of scale changes and their spatial variation provides an important part of my understanding of urban change and its impacts, positive and negative. In addition, understanding scale and how it changes may shed light on answering a number of questions, such as how scale impacts livability, pedestrian quality, access, affordability, or crime. In order to delve into these and other scale-related topics, urbanists need an approach to scale measurement and analysis.

This three-part analysis of historical progression, block scale and tract scale provided a way to visualize and quantify scale change in one large U.S. city. Quantified evaluation of scale is important for several reasons. First, although scale is an essential factor in urban development, current understanding of it is improvised at best. This study made an attempt to translate scale from ad hoc understanding to meaningful empirical research. Second, if planners are going to advocate for a particular side in the scale debates—and most city planners seem to be advocates of small-scale development—they need a more developed set of arguments about why a particular scale matters. This study provided empirical evidence that small-scale urbanism is capable of delivering quantified benefits: significantly more square footage, higher pedestrian quality, and higher unit type diversity. The association with higher income and higher housing value attests to its intrinsic desirability, but it also shows the need to ensure equitable access and to address the associated gentrification and displacement issues. Finally, by mapping and measuring scale changes over time, it is possible to provide a more detailed understanding of scale and how urban fabric has evolved, insights important to our understanding of urban place quality.

I am not able to conclude that the context of large-scale buildings is one of more degrading factors than small-scale buildings. Nor do large-scale buildings have lower levels of mixed use or daily life uses compared to small-scale buildings. I was, however, able to show that scale 2 buildings—missing middle housing in 2–4 unit structures, with buildings under 12,000 square feet and under 4 stories—are associated with higher block character than other scales. This may have to do with the relatively historic quality of many scale 2 buildings and my inclusion of historic buildings as a variable in calculating block character. Had I conducted this analysis in a city with more historical four, six, or nine story buildings, I may have found different results.

Also of note are the dramatic differences in total square footage between the historic and redeveloped city. Of the 31 redeveloped sites examined, total square footage shrank by over three-quarters, mixed uses declined from almost 20 to down to 2%, while the number of residential units stayed relatively the same. While my buildings have gotten larger, they now provide significantly less interior space for social and economic activity. Could that former space have been put to better use as either affordable social housing or small-scale industrial, institutional, or commercial uses? These findings suggest ample room for urbanists to push for the inclusion of more mixed uses and affordable housing in development projects receiving government subsidies.

Several limitations in my method need to be acknowledged. First, the inclusion of just 31 historical sites was somewhat opportunistic and necessarily selective, so generalizations about scale change for the city as a whole, or for other cities in the U.S., is limited. Second, the scale typology and block score calculations included judgement calls about cut-off points, variables to include or exclude, and estimations needed to fill in for missing data (e.g., estimation was needed for some building height calculations). This kind of variability introduces the possibility that different kinds of measures and variables would yield different outcomes, signaling the need for a sensitivity analysis. It is also important to acknowledge that other variables important for gauging pedestrian quality were not included, such as street frontage continuity and sidewalk-facing entrances. This was only one approach to analyzing scale, selected because of the quantitative nature of the study. Other methods are needed to gauge scale in ways that better capture its relation to urban space quality, access, forms of movement, and modes of travel.

It is also important to realize that more recent mega-developments than the ones I surveyed might be more sensitive to design problems. This brings up the question of whether certain issues I’ve uncovered have more to do with design than scale, meaning that a better design—rather than a smaller scale—might be capable of resolving some issues. It may be true that my results indicating an association between large-scale projects and reduced pedestrian quality are specific to certain eras (pre-2000) and places (rust-belt cities like Chicago). Megaprojects in cities like Washington, DC, especially those built since the 2000s, often have no surface parking, plenty of underground parking, and connections to transit—all of which is likely to resolve some of the quality-related liabilities. In addition, design regulations in places like Vancouver, BC have successfully recreated the more integrative connections between building frontage and sidewalk that smaller scales traditionally accomplished.

These are open questions. However, as tensions exist between proponents of small vs. large scale urban development, additional research is needed to examine the role scale might play in promoting sustainability, livability, affordability, and social diversity. What is the relationship between scale and community cohesion, support for small business, and neighborhood investment? A better awareness of these phenomena and relationships would help residents, designers, and policymakers understand the impact of proposed scale changes.

Incremental urbanism is distinguished by being in direct opposition to top–down, capital intensive, and bureaucratically sanctioned urban change of the kind most often associated with urban planning. There is a need to understand the impact of scale associated with these kinds of investment strategies—an evaluation that goes beyond economic calculation.