Abstract

The timely implementation of climate adaptation measures for the urban environment is essential to the creation of robust cities. Within Norway, these adaptation measures are undertaken at the municipal level. Unfortunately, the implementation of adaptation measures has lagged behind expectations, partially due to public resistance to local projects. City planners seek tools to provide insight into the priorities of residents to build consensus and public support. This study follows up on two previous case studies of Sustainable Urban Drainage System (SUDS) implementation in Trondheim, Norway, where the prioritization of urban space is often a source of conflict. The Hofstede Cultural Compass is a tool that maps six cultural dimensions used in research and practice to inform users about cultural norms and cross-cultural divergences. This study seeks to test and verify this tool for use in building public consensus and support. Municipal managers responsible for project implementation took the Cultural Compass survey, and the results were collectively mapped and compared to the public at large. The Cultural Compass found notable divergences between the municipality and the Norwegian public within the areas of “Long-term Orientation”, “Uncertainty Avoidance”, and “Masculinity vs. Femininity”. These findings were cross-referenced with thematically analyzed interviews of residents regarding their perceptions of a municipal SUDS project. Together, these case studies give greater insight into the issues of diverging priorities and perspectives experienced in the implementation of SUDS. Recommendations are presented to aid the understanding of intercultural divergences between planning offices and public priorities in an effort to better engage the public and build consensus.

1. Introduction

1.1. Climate Change and Urban Flooding

The International Panel on Climate Change has projected that the Nordic countries will be disproportionally affected by global climate change [1]. The most notable of these changes will be an increase in temperature, precipitation, intensity, and frequency of rain events [1,2]. Currently, Norway’s average annual rate of precipitation is 20% higher than it was 100 years ago, with an additional 20% increase projected by the end of this century [3]. The negative impacts of torrential rain are already evident within the built, urban environment and are considered the greatest technical challenge Norway faces from climate change [4,5,6,7,8]. These intensified loads add further strain on surface water drainage, burdening aged, outmoded infrastructure within Norway’s existing urban environments, which are already beyond capacity [6,9]. The burden on these systems is exacerbated by continued densification of cities and the loss of permeable surfaces, raising the risk of flooding in localized events and increasing risks to buildings and infrastructure [9,10].

1.2. Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems, SUDS

To address the specific challenges of managing water in urban environments, Norway has adopted policies and regulations at the national level. The Norwegian Water Directive is drawn from the European Union (EU) Water Framework Directive and is intended to protect the environmental status of all ground and surface waters within Norway [11,12,13]. Within these guidelines, Norwegian municipalities are directed to employ sustainable urban drainage systems (SUDS) [7].

Traditional closed systems, such as sewer systems, have limited capacity to detain or purify accumulated surface water [14]. In response to the limitations of traditional water management systems, the Norwegian Water Directive has prioritized the use of passive SUDS [15]. SUDS manage surface water by introducing natural elements such as riparian buffers, vegetative filters, rain beds, water spills, watermark filters, retainers, and dams rather than active mechanical installations [15,16,17]. SUDS have been promoted at the political and bureaucratic levels as affordable, cost-effective solutions that provide added value for the public, such as experiential spaces [18,19,20].

In contrast to subterranean gray infrastructure, SUDS often visibly change the urban environment. This shift in what flood risk management and water treatment involve and look like also draws greater public scrutiny to their installation and maintenance [21]. How the use of space is prioritized in urban areas is often a source of conflict [22]. At the municipal level within Norway, SUDS projects both proposed and undertaken have at times received strong public resistance [23,24,25,26]. Gaining local community support for SUDS requires a greater understanding of public priorities and expectations in both the functions of SUDS and engaging the public to build consensus. O’Connor and Levin [27] recommend using mental models as cognitive frameworks to understand complex systems, identify stakeholders, and promote communication and collaboration among diverse groups. They note that “addressing the stormwater problem requires that we embrace the varied perspectives of scientists, managers, and stakeholders” [27].

1.3. Climate Adaptation within Norway: Implementation and Preception

In Norway, the adoption and implementation of climate adaptation measures within the urban environment is a public process. This process requires coordinated planning processes across various authorities and the active participation of all types of users. When addressing urban water issues, this responsibility is led by a water area committee and undertaken at the county municipal level within each water region. The water area committee provides local knowledge and generates local proposals for these climate adaptation measures [28]. Despite these structures within the framework, it has been found that there is a great need for more knowledge in the implementation of climate adaptation measures and support processes [29].

While proper climate adaptation measures can safeguard Norway’s urban environments, the introduction of adaptation measures is often arbitrary. Implementation at the municipal level often fails [30], and the local adoption of climate adaptation projects has “lagged behind expectations” [29]. Notable challenges to implementation have included conventional attitudes toward planning, resistance to change, and unequal access to and engagement with support networks [30]. It is recommended that within Norway, “…climate adaptation guidelines and other tools are necessary to support planning and other decision-making processes. Effective climate adaptation consequently depends as much on structures and processes as on technical concepts and solutions” [31].

Presently, larger municipalities are able to better execute climate adaptation measures than smaller municipalities [8,32]. To address these challenges, initiatives such as climate adaptation networks comprised of governmental, industry, and academic partnerships have been created at the national level. The directive of these networks is to increase awareness at the municipal level of how to manage climate challenges [33,34]. Municipalities within these networks have undertaken far more adaptive planning and executed more projects and measures than unaffiliated municipalities [8]. Recommendations have been made for greater cooperation between municipalities to create and share competence [32]. Research has also called for increased interdisciplinary competence in strategy, planning, and project management [32].

1.4. Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Theory

Geert Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory is a framework used to analyze and quantify social values and behaviors in an organizational or national culture [35]. Six cultural dimensions are used to create an overall quantified assessment of values, which can be used for comparisons between different cultures. The six dimensions are: power distance, individualism vs. collectivism, masculinity vs. femininity, uncertainty avoidance, indulgence vs. restraint, and short-term vs. long-term orientation. The theory was developed for cross-cultural communication and initially used to improve management of different international branches within a large corporation [35]. However, it has also been found to be applicable for analyzing the values of a single organization or comparing different organizations within the same country, as well as at an individual level [35,36].

1.5. Objective and Scope

This study is a follow-up on two previous studies on SUDS projects in Trondheim. The first study investigated themes of public perception of SUDS management using the brook Blaklibekken as a study case [26]. The second study investigated the ongoing brook restoration of Fredlybekken, which has been partially stalled due to local resistance [37]. The present study investigates the cultural aspects of why conflict arose over these two projects. Recommendations are also given on municipal-public communication for the implementation of future SUDS projects.

The swift adoption of SUDS is considered an essential measure for climate adaptation and the management of urban water, but a lack of public acceptance can be a barrier to their implementation. The present study seeks to test and verify the Hofstede Cultural Compass Tool for use in building the public consensus and support necessary for timely implementation of SUDS measures. The research includes quantitatively mapping diverging priorities and cultural norms between the local governing municipal planning agency and the public at large. These findings are cross-referenced with a thematic analysis of documented texts and interviews with both the municipality and residents to verify the results of the Hofstede cultural compass tool.

Our intention is to better understand:

- What variability exists between the scores of municipal actors and the public within Hofstede’s six dimensions?

- Does a thematic analysis of texts and interviews with municipal actors and local users verify the findings of the Hofstede cultural compass tool?

- What recommendations can be drawn from the discrepancies between the culture of the municipal planning office and the local public to better inform the decision making and planning processes of SUDS?

2. Case Studies: Brook Restorations in Trondheim, Norway

Trondheim, with a population of 212,660 as of January 2023, is the third most populous municipality in Norway [38]. Approximately half of the municipal drainage network, which manages both sewage and overflow, is currently piped [24]. Much of this piped area was once a naturally occurring drainage tributary that spilled into Trondheim’s main river, the Nidelven, and the Trondheim fjord. Today, the aging infrastructure within the urban environment is beyond functioning capacity, and increased stormwater runoff due to urban development and climate change has further compromised the integrity of the existing stormwater system [24,39]. To answer these challenges, the Trondheim municipality is working to incorporate SUDS into the planning process under the directives of the Norwegian Water Management Directive.

Examples of SUDS include the restoration of tributary brooks to the Nidelven River, many of which were piped around the middle of the 20th century. The present study investigates two cases of brook restoration south of Trondheim: the piped brook Blaklibekken, which was restored in 2010, and Fredlybekken, whose restoration is ongoing but partially stalled.

2.1. Blaklibekken

The Blaklibekken case study is located at the southern end of the Risvollan township (63°23′24″ N, 10°26′09″ E). The area was previously farmland but, since 2005, has been developed as a mixed-use residential area. A large facility owned by a commercial organization and a transformer station abut the north end of the site, while a public sports hall is located at the south end. Adjacent to both the west and east sides of the site is residential development, a mix of occupant owned apartment blocks and townhouses. A children’s daycare borders the northwestern section of the site. The construction of multi-family apartment blocks adjacent to the east side of the site continued at the time of this article’s publication.

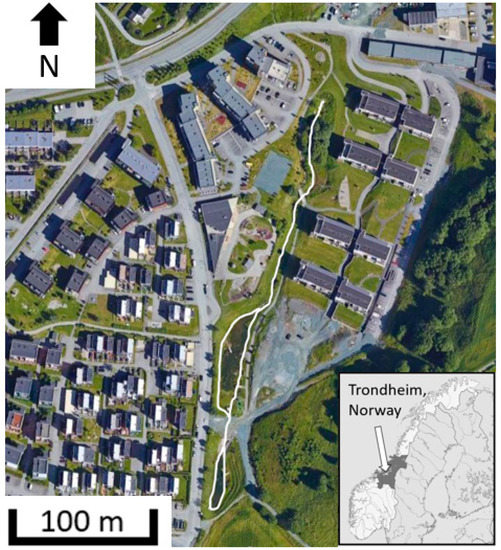

The Blaklibekken site, seen in Figure 1, is designed as a diversion facility for surface water discharged from the surrounding areas. The facility consists of a 400-meter-long, green corridor with retention and detention ponds, as the piped system downstream has limited capacity. The site was designed to function as a multi-functional SUDS project that incorporated public recreation into stormwater management infrastructure. A footpath runs along the length of the site, from north to south. There is a small bridge crossing the north pond. Additionally, small docks jut over both ponds. The site originally included several play fixtures, both fixed and loose, dispersed across the area.

Figure 1.

Aerial view of Blaklibekken site (Maxar Technologies, Map data © 2022).

For the first three years of operation, the site was managed by the developer of the neighborhood; after that, Trondheim Municipality took over management and maintenance.

Initially, after completion, the project was met with a generally positive response. However, within two years, the municipality started to receive complaints about the site regarding water quality, overgrowth, and a general lack of maintenance. The frustration of residents was voiced in articles in local newspapers, and complaints were logged with the political board. Local community groups protested the introduction of proposed SUDS projects in other neighborhoods, citing the various problems with the Blaklibekken site [16,23,25,29].

A previous study was conducted in 2021 to map the perspectives and challenges surrounding the Blaklibekken project [26]. Community outreach was found to be lacking within the project, especially in the decision-making phase. Throughout the project, the purpose of the SUDS area was poorly clarified, communicated, and formalized through its design, creating a discrepancy between public expectations and observed performance [26].

2.2. Fredlybekken

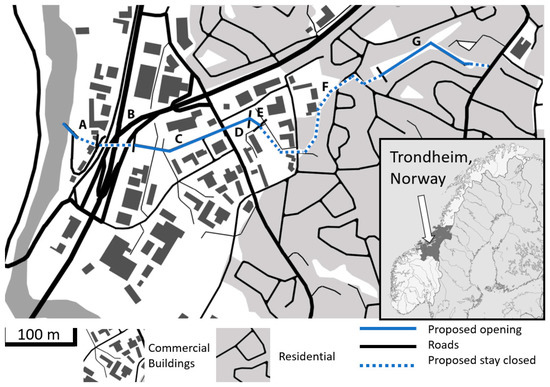

The brook Fredlybekken is approximately 2.5 km long and runs through the Sluppen neighborhood of Trondheim, south of the city center. Fredlybekken was piped in the 1950s, when the area was built out for industrial, commercial, and residential purposes. The pipe is part of a combined sewage and drainage system that overflows directly into the Nidelven River. The area has seen substantial densification in recent decades, which has increased the strain on the drainage network and caused overflow events to occur 1000–1500 h per year, with diluted sewage spilling into the Nidelven River [24,40]. To mitigate the situation, the Trondheim municipality has proposed a major rejuvenation of the Fredlybekken. The entire length of the brook is shown in Figure 2. The sections proposed to remain piped (B, F) are shown as dotted lines, while the sections proposed to be opened (A, C, D, E, and G) are shown as solid lines.

Figure 2.

Overview of the Fredlybekken and the various sections (A–G) of the rejuvenation proposal. The Nidelven River is to the left.

Section G of the Fredlybekken runs through a residential area and is the longest section planned to be opened. It is proposed to feature ponds, retainers, riparian buffers, and greenspaces with a walking path [41]. The proposal has been met with substantial local resistance. Residents have cited concerns about costs, land use change, and health and safety [42]. The issues experienced with the Blaklibekken project are cited as an argument to reconsider the Fredlybekken proposal. Together, the two case studies give great insight into the issues of diverging priorities and perspectives between residents and planning authorities that may be experienced in the implementation of SUDS in built-up areas.

3. Theoretical Framework

A psychological approach offers valuable insight into typical challenges found with human behaviors, perceptions, and motivations towards our natural environment and how we engage with these spaces [43,44,45]. A distinctive feature of this approach is ‘the recognition, even embracing, of the value of multiple perspectives on issues’ [46]. Applying this approach to the research questions posed within this case study can inform our understanding of local perspectives and how to build consensus and support for SUDS.

3.1. Ethnography and Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions

This research is framed within the ethnographic dimensions of Scandinavian culture and has been presented through the lens of the Hofstede Cultural Compass, which is derived from the Hofstede Cultural Comparison Model. Qualitative, ethnographic models study complex social environments and the meaning that people within those environments bring to their experiences [35,36]. This approach looks at people in their cultural setting with the goal of producing a narrative account of that particular culture and its cultural codes. These ethnographic considerations inform the findings of this research by relating the scientific description of the people and culture of Scandinavia to their customs, habits, and differences [36]. In qualitative research, the analytic generalization of results depends on a comparison; contextualizing informs generalizations that the reader may take from the results when applying these findings to other situations, cultures, and societies [47].

Culture is defined as “the collective mental programming of the human mind that distinguishes one group of people from another. This programming influences patterns of thinking, which are reflected in the meaning people attach to various aspects of life and which become crystallized in the institutions of a society” [36]. The Hofstede scores are generalizations and do not imply that all members of a given society are programmed in the same way, while also recognizing that there are considerable differences between individuals within the group [36]. Nonetheless, Hofstede’s country scores are based on the “law of big numbers” and the assertion that members of a society are strongly influenced by social controls [36]. Additionally, the dimensions of one culture’s values can only exist relative to another comparative culture; “without comparison, a cultural score is meaningless” [36]. These dimensions can be applied at the national level, corporate level, and individual level to provide feedback tailored to the specific interests of a user.

3.2. Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Model

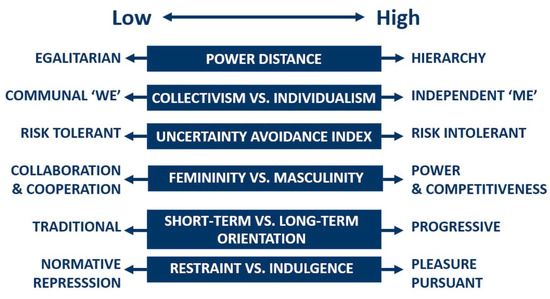

Hofstede’s model contains six different cultural dimensions: Power Distance (PDI), Individualism versus Collectivism (IDV), Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI), Masculine versus Feminine (MAS), Long-Term Orientation versus Short-Term Orientation (LTO), and Indulgence versus Restraint (IVR); see Figure 3. The model scores the dimensions from 1 to 100 with high or low scores affirming stronger linkage to one or another side of the spectrum. To read and interpret these scores, it is important to keep in mind that the scores are relative to each other and not absolute. That is, the scores for one culture should be compared to the scores for other cultures to understand the differences in cultural values. For example, a country with a high PDI score (e.g., 80) would have a more hierarchical and formal society where people are expected to respect and defer to authority figures. On the other hand, a country with a low PDI score (e.g., 20) would have a more egalitarian society, where people are more likely to challenge authority and expect equality. The score does not indicate whether a cultural norm is better or worse, but only as it compares to other cultural norms. It is important to note that these scores are not fixed and can change over time as cultural values and attitudes evolve. Additionally, the scores are based on generalizations and should not be used to make assumptions about individuals from a particular culture.

Figure 3.

Hofstede’s six cultural dimensions.

POWER DISTANCE (PDI)—reflects the extent to which power is expected to be distributed unequally. A high score reflects that hierarchy is clearly established, while a low score indicates that authority is questioned and a distribution of power is expected.

INDIVIDUALISM VS. COLLECTIVISM (IDV)—reflects the degree to which people are integrated into societal groupings or an “I” or “We” mentality within a society. The individualistic “I” has loose ties that often only relate to an individual and their immediate family versus the collective “We”, which emphasizes tightly integrated relationships and extended family and social ties, where the group takes priority over the individual.

UNCERTAINTY AVOIDANCE INDEX (UAI)—defined as a society’s tolerance for ambiguity; the acceptance or aversion to the unexpected, unknown, or that which is outside of status quos. High scores indicate stiff codes of behavior, guidelines, laws, and a “one truth belief system”. Low scores impose fewer regulations and codes, are more accepting of differing thoughts or ideas, and foster a flexible environment.

MASCULINITY VS. FEMININITY (MAS)—masculinity prizes competition, achievement, assertiveness, and material success. Femininity represents a preference for cooperation, modesty, welfare, and quality of life.

LONG-TERM ORIENTATION VS. SHORT-TERM ORIENTATION (LTO)—a high index of long-term orientation reflects a social view of adaptation, flexibility, and pragmatic approaches applied for circumstantial necessity. A low index of short-term orientation suggests greater social rigidity and a prioritization of honoring traditions and long-established approaches and practices.

INDULGENCE VS. RESTRAINT (IND)—this dimension reflects the degree to which societal norms tolerate a member’s individual preferences and desires. A high index allows relatively free human gratification in the “enjoyment of life and pursuit of fun”. Low scores indicate societal controls that regulate personal gratification through strict social norms [26].

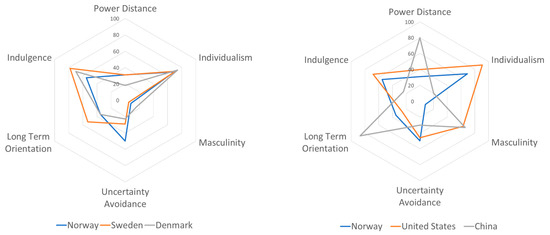

The ethnographic nature of the research and findings from a Norwegian case study may be relevant to projects situated in other locations, cultures, and countries. We attempt to provide an overview of the deep drivers of Norwegian culture using Hofstede’s models and tools, allowing for comparisons. Figure 4 should be of note when comparing cultures within this paradigm to illustrate examples of cultures with closely aligned values and cultures with notably divergent priorities. While the Scandinavian countries score within close range of each other on all the dimensions (Figure 4, left), there is considerable disparity between Norwegian cultural norms and those of China and the USA (Figure 4, right). These charts are shown as an example of mapping convergent and divergent dimensions, while the findings of the present study look at mapping the results of subgroups within Norway. Therefore, the findings of the presented study may be more readily applicable within the Scandinavian context, while further considerations must be made when applying these findings further abroad.

Figure 4.

Examples of Hofstede survey results. (Left): comparison of cultural dimensions between similar countries: Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. (Right): A divergent cultural comparison between country dimensions: Norway, the United States, and China [48].

4. Methodology

The present study examines the public perception of two SUDS case studies and how the discourse between the municipality and local users/residents has either reinforced or diverged from cultural expectations. The identification of divergencies is key to assessing the acceptance of these sorts of projects. To assess the validity of the Hofstede Cultural Compass Tool within this context, the authors used a mixed-methods approach to evaluate and validate the findings. This included:

- Literature review;

- Document study;

- Interviews;

- Surveys;

- Thematic Analysis.

Parts of the data (the document study and the interviews) have already been processed and presented in a previous study by the authors [26]. The present study uses these data to inform the analysis of the surveys and the literature review. For context, the methodology used for the previous study is summarized in Section 4.2 and Section 4.3.

4.1. Literature Review

A literature review was undertaken to investigate and compare previous international scientific studies on public attitudes towards SUDS implementation. Searching in Google Scholar, the terms “SUDS” and “Stormwater management” were paired with “perceptions”, “public”, “residents”, “attitudes”, “opinions”, and “conflict”. Using the “snowballing” method [49], the bibliographies of retrieved articles were also consulted to find other relevant studies. 20 studies were identified, of which 15 were of particular interest and subject to further analysis. The studies were listed in a spreadsheet to compare their research objectives, research methodology, the types of SUDS or stormwater management measures investigated, their general findings, and any recommendations given to planning authorities.

4.2. Document Study

The present analysis was informed by an overview of existing documentation of the case studies. They provided the historical background of the site and assessments of the performance of the SUDS system. The overview included a review of all available project documentation, public records, site evaluation reports, and newspaper articles. This documentation spans the years 2010–2022. All translations followed ISO 17100:2015, the international standard for translations. The reviewed texts included:

- One consultancy evaluation [41];

- Nine Norwegian University of Science and Technology engineering evaluations;

- Seven municipal planning commission summaries;

- Six newspaper articles;

- One regional SUDS feasibility study;

- One national review evaluation;

- One municipal plan.

4.3. Interviews

This is a study that builds upon the collective results of two previous studies with the intention of providing greater insights across case studies. Interviews were conducted at both sites. Qualitative interviews were conducted as an open-ended approach to provide participants with the freedom and flexibility to describe their own understanding and experiences of the Blaklibekken and Fredlybekken sites and engagement processes. These interviews were semi-structured, following the prescriptions of Yin (2009) and Kvale and Brinkmann (2014) [47,50]. The intention of the interviews was to assess the participants’ impressions and whether they felt that their expectations had been met. Key to the process were personal opinions and impressions, values, and priorities. This was undertaken to determine whether any common perceptions existed among the public, which would influence the overall acceptance and satisfaction of the project. It was not part of the study to gauge the public’s actual understanding of the engineering and scientific principles behind the project or its policy/regulatory legitimacy.

4.3.1. Semi-Structured Interviews with the Municipality

To record what commonalities and variants of opinion existed between the municipality and users of the site, an interview with key municipal personnel was conducted. One common interview was carried out with the project leader for the Blaklibekken project and a municipal representative from “Kommunal Teknikk VA” (Municipal Engineering, Water, and Wastewater). The interview was conducted by phone on 27 June 2020. Notes were taken throughout to document the responses of the participants. The municipality was also asked to provide the context in which the project was undertaken, an overview of the project’s history, and a summary of the current challenges to the site as identified by the municipality. They were also given the opportunity to give their response to local newspaper reports about the project. To protect the privacy of the actors, their identities have been withheld.

4.3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews with Blaklibekken Area Users

A total of 100 residents or local users were interviewed on-site at Blaklibekken and the surrounding adjacent neighborhood, which provided a statistically relevant sample size. The interviews were conducted over a week-long period between 30 June and 6 July 2020. The interviews were short and semi-structured. The following requirements applied to participants in the interviews: the person must be a local resident whose property abuts the sites and/or a local who uses the public space on a regular basis (once per week or more often). While quotes pertaining to the impressions of the residents and locals have been included, their identities have been withheld to protect their privacy. Open-ended questions gave participants the opportunity to share their opinions, observations, and recommendations. The majority of respondents (83%) were not familiar with the area prior to the project’s completion. A more detailed description of the demographics of the interview respondents can be found in a previously published study by the authors [26].

4.3.3. Semi-Structured Interviews with Fredlybekken Residents

Qualitative interviews were conducted with residents who were protesting against the Fredlybekken project. The interviews utilized an open-ended approach to allow participants to freely express their experiences and understanding of the site. The interviews were semi-structured and aimed to capture the residents’ and users’ opinions of the project’s value and necessity and to identify common perceptions that may influence the project’s acceptance among the residents. It should be noted that the interviews did not focus on assessing the public’s understanding of the project’s technical or regulatory aspects. Rather, the focus was on the public’s perceptions and opinions. The number of interviews at the Fredlybekken site was limited by the number of residents (72) who were members of the “Fredlydalen Velforening” neighborhood resistance group.

4.4. Hofstede Cultural Survey

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory is a framework for cross-cultural communication. Using a structure derived from factor analysis, it shows how a society’s culture and values affect its members and how these values relate to behavior [36]. The analysis of cultural dimensions is based on a survey and analysis available online from the Hofstede Institute [51].

Respondents are presented with pairs of statements and asked whether they agree, strongly agree with one statement or the other, or feel neutral. There are 42 pairs of statements in total, seven for each of the six cultural dimensions. The responses are then analyzed to determine a score for each of the dimensions. The scores of the respondent can be compared against the national average to show how their responses differ from the national average or within the organization.

The Hofstede cultural compass survey was administered to 10 key individuals familiar with the site, general project managers within Trondheim municipal planning offices, and representatives of the local protest group against the Fredlybekken project. The intention was twofold: to collect individual opinions within the municipality among project managers and to validate whether Hofstede’s database scores for the Norwegian public reflected those of the residents with sufficient accuracy. Respondents completed the survey in private on paper, and the results were kept confidential to respect the privacy of the participants and not unduly influence future participants answers. The Norwegian surveys were then tallied and the responses averaged, then rounded off to the closest digit on a five-point scale. A score of 1 would correspond to strong agreement with statement A, 5 would be strong agreement with statement B, and 3 would represent neutrality. This averaged tally was then entered into the Hofstede online survey to obtain cultural dimension scores for the culture of Trondheim Municipality’s planning office and for the protest group. These scores were then compared to the Norwegian national averages as collected in Hofstede’s database. Within the results of this research, differences between the results of all six indicators were mapped. The researchers focused on the three indicators that had substantial divergences of 20 points or more.

4.5. Reflexive Thematic Analysis (TA)

Reflexive thematic analysis does not merely summarize and organize the data but provides an analyzed interpretation of it. Here, the prescriptions of Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step framework for thematic analysis were followed [52,53]. Replication of this method can be achieved following Braun and Clarke’s (2013) recommendations and the practical step-by-step guidelines laid out by Maguire and Delahunt [54]. This six-step framework is not necessarily linear, and the researcher may move between steps many times. It should be noted that the results of reflexive TA are both flexible and variable. The conclusions have been drawn from the findings of one coder with an iterative committee for oversight. The findings drawn from this work have been generated and occur at the intersection of the data and the researcher’s interpretative framework and assumptions. Braun and Clarke’s six-phase framework for doing a thematic analysis involves:

- Step 1: Become familiar with the data

- Step 2: Generate initial codes

- Step 3: Search for themes

- Step 4: Review themes

- Step 5: Define themes

- Step 6: Write-up

4.6. Thematic Coding

Within this context, we review the cultural codes of Norwegian society as outlined by Geert Hofstede’s Six Dimensions of Culture Model. To map these dimensions, a sample of project managers within the municipal planning office were surveyed using the Hofstede cultural compass tool. The resulting map was then cross-triangulated with a thematic analysis of documented text and responses from interviews with both the municipality and the residents in the case study. This was undertaken to identify whether the priorities, values, and social codes of the municipality corresponded to those of the residents. This was carried out to infer whether the municipality’s engagement with the public reinforced or diverged from general Norwegian society’s values, priorities, and codes. The aim was to evaluate the assumed effectiveness of the Hofstede cultural compass tool and determine whether this easily accessible tool may be a resource for municipal planners in building consensus and public support for SUDS projects and other climate adaptive measures.

Categorized statements from articles and public records were reviewed in consideration of the Geert Hofstede Cultural Model to evaluate whether these statements suggested an experience that reinforced or diverged from Norwegian cultural expectations and findings drawn from the results of the Hofstede cultural compass tool. A thorough review of the findings from the document study, semi-structured interviews with the municipality, and semi-structured interviews has already been published, presenting themes of public interest [26]. Building off this work, a matrix was constructed to allocate all the statements collected pertaining to the three cultural dimensions focused on in this paper: LTO, UAI, and MAS.

Statements regarding public perception and priorities in these three dimensions were collected and cataloged by source. These statements then went through a review process that categorized relevant statements by dimension. It was then determined whether the statements reinforced or diverged from the findings of the cultural compass tool, which are presented as percentages to illustrate the degree to which the statements reinforced or diverged from the findings. Providing a quantitative result that can be replicated and compared in future work.

5. Results

5.1. Literature Review

The findings of the literature review are summarized in Table 1, with detailed findings elaborated below. Sixteen studies on public attitudes towards SUDS and stormwater management measures were found, originating chiefly from the UK and the US. Four of the studies [55,56,57] were literature reviews.

Table 1.

Overview of the literature survey results.

Qi and Barclay [55] and Feng and Nassauer [56] investigated social barriers to stormwater management implementation on the individual level. Both found that preconceived opinions and attitudes played a major role in the individual’s acceptance of stormwater management measures. Feng and Nassauer recommend that the economic benefits of stormwater management measures be communicated more clearly to improve community perceptions. Everett et al. [57,59] sought to develop a framework for the community to engage with blue-green infrastructure. It is recommended that community engagement begin early in the planning process and be maintained throughout the lifetime of the project to improve community awareness and understanding.

Eleven of the identified studies involved surveying members of the public about their attitudes toward SUDS and stormwater management measures. While some studies asked respondents to rate their opinions on examples of SUDS shown in pictures, others collected opinions and attitudes towards SUDS existing in the local area. The location of the SUDS in the latter type of study was typically a nearby park or established greenspace, often close to a residential area. Two studies [60,61] also concerned small-scale measures (rain beds, rainwater barrels, permeable pavement) that could be installed by individual homeowners on their own lots. The final of the 16 studies interviewed practitioners responsible for stormwater management in two cities in the US [62]. Barriers to the implementation of stormwater measures were investigated from a management and economic perspective.

A common theme among survey responses was the importance of “beauty” for the public’s acceptance of SUDS, or stormwater measures. Respondents in several studies were found to give preference to picturesque ponds or landscapes [63,64,65,66,67], although the perception of beauty or what looked “natural” often did not coincide with effective stormwater management. O’Donnell et al. [65] found that respondents often preferred greenspaces without SUDS at all, finding them “more attractive, tidier and safer”. Nassauer et al. [58] also remark (in the context of rivers) that public expectations of aesthetics may not align with hydrologic and ecological performance.

A similar lack of awareness, understanding, or prioritizing of SUDS benefits among the public was also found to be a barrier to implementation in other studies, and they recommend promoting information about these benefits to improve awareness and acceptance. Williams et al. [67] found that most respondents did not perceive that SUDS increased property values. Jarvie et al. [68] addressed the issue of willingness to pay for ponds, finding that the economic benefits of ponds outweighed the expense of maintaining them but that the benefits were often not well communicated. Zamanifard et al. [69] found that the public was generally positive about the bioretention basins they were presented with in their area, but that awareness of their function was low to the point that fewer than half of the respondents could identify their purpose. Lack of awareness may lead to the de-prioritization of maintenance in the long term.

Common themes were also found among survey respondents’ perceived drawbacks of SUDS. Concerns about litter, pests, and maintenance tempered the generally positive impressions of the green space in the studies by Williams et al. [67] and Zamanifard et al. [69]. The perception of health and safety risks was also highlighted by Jarvie et al. [68] and Bastien et al. [70]. Gazzard and Booth [66] conclude that “(…) changing public perceptions of ‘blue-green infrastructure’ will remain an obstacle until awareness of its value is far-reaching and celebrated beyond the confinements of architectural drawings and planning applications”.

Conflict was not found to be a theme in any of the investigated literature. The SUDS and stormwater measurement systems were often adjacent to residential areas or in the middle of neighborhood parks. It is uncertain whether any facilities were constructed close enough to residences, physically and temporally, to be considered “encroaching” on residential space. No examples were found of facilities whose installation was highlighted as being contested by the residents.

It is also noted that several studies propose to improve communication between planning authorities and residents/users, but beyond stating the need to convey specific information (i.e., benefits to the environment, stormwater management functions, or economic benefits) or involving residents/users early in the planning process, no advice was presented on what improved communication might entail in practice.

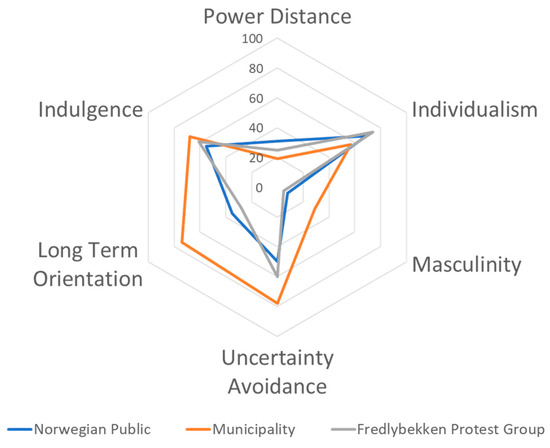

5.2. Hofstede Cultural Survey—General Public and Municipality

Our intention is to better understand what variability exists in Hofstede’s six dimensional scores between municipal actors and Hofstede’s established scores of the general Norwegian public. Three dimensions showed a dramatic deviation (≥20 pts.) between the municipality and the public. The protest group scored similarly to the Norwegian public as catalogued by Hofstede, with <10 points difference in every category. This difference is too small to be considered a notable deviation, according to Hofstede [71].

Figure 5 illustrates the findings of the surveys. The blue line represents the general public of Norway; the score of the Fredlybekken protest group is shown in gray; and the score of the participating municipal project managers is shown in orange. The results of the survey found the greatest divergences between the municipality and the public within the dimensions of LTO (+39), UAI (+28), and MAS (+21). The additional three dimensions had less divergent scores of 12 points: PDI (−12), IDV (−12), and IVR (+12). The dimensions of LTO, UAI, and MAS have been selected for further analysis due to the dramatic spread of these three most notable diverging dimension scores.

Figure 5.

Results of the Hofstede cultural compass survey.

6. Variability, Verification, and Recommendations

The following section is drawn from the prescription of the Hofstede cultural dimension comparison model and applied by the researchers with specificity to the Trondheim municipality. Statements from interviews and document studies that reinforce or contradict the findings are discussed in the sections below.

Three research questions were formulated for the study. The sections below discuss a deeper analysis of the dimensions LTO, UAI, and MAS in the context of these research questions. The three dimensions that are presented represent the greatest divergences between municipal and public responses. Each dimension is presented in its own subsection, answering the questions: (1) What variability exists in Hofstede’s six dimensional scores between municipal actors and the scores of the public? (2) Does a thematic analysis of texts and interviews with municipal actors and local users verify the findings of the Hofstede cultural compass tool? (3) What recommendations can be drawn from the discrepancies between the culture of the municipal planning office and the local public to better inform the decision-making and planning processes of SUDS? Recommendations are provided to the municipality as an authoritative body, as a negotiator, and in communications with the public.

6.1. Long-Term Orientation versus Short-Term Normative Orientation (LTO)

+39 points towards long-term orientation

- (1)

- The low score of 35 indicates that Norway has a more normative than pragmatic culture. People in such societies have a strong concern with establishing an absolute truth; they are normative in their thinking. They exhibit great respect for traditions and norms while viewing societal change with some suspicion. This score also correlates with a relatively small propensity to save for the future and a focus on achieving quick results. The municipal score of 74 is 39 points higher than the general population, which is of particular note as it is the largest divergence registered among all the dimensions. The municipal score reflects the municipality’s tendency to take more pragmatic approaches, encourage thrift, and make efforts to plan long-term to prepare for the future;

- (2)

- This dimension had the strongest correlation between the results of the survey and the thematic analysis of the transcripts. The results of Hofstede’s findings were confirmed, with 91% of the 47 statements affirming this divergence. Statements such as, “We don’t understand why they (municipality) had to change things?” (Resident interview #54), “It was fine the way it was before” (Resident interview #72), “They are frustrated because they (residents) expect quick results” (Municipal interview #2), and “I don’t think they (residents) necessarily understand the long-term benefits of these projects” (Municipal interview #1). A total of 100% of the municipal statements affirmed the findings of the LTO dimension, while only 75% of the public statements affirmed the findings. It is also of note that 65% of the total collected LTO statements were made by the municipality, which also confirms the municipality’s greater focus on LTO goals;

- (3)

- Based on these findings, the following recommendations, drawn from Hofstede’s cultural theories, are applied specifically to the Trondheim case.

As an authoritative body:

- The municipality may be underestimating the importance of pleasant relations with the public and serving the public’s self-interests;

- Municipal actors may be annoyed by the fact that the public is not proactive concerning their desires and wishes.

In negotiating with the public:

- If the municipality offers inconsistent information to the public, they may no longer be credible, as the public thinks in exclusive, not inclusive, terms;

- Municipal actors may be upset by the outspoken way the public presents themselves, expecting them to show more humility.

In communication with the public:

- They may demotivate the public by overloading them with details without giving them the overall picture;

- Municipal actors may be upset that their wisdom is questioned by the public;

- Municipal actors may not feel that they are paid the respect they deserve.

6.2. Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI)

+28 points towards uncertainty avoidance

- (1)

- Norway scores 50 and thus does not indicate a clear preference in this dimension. The municipal score on uncertainty avoidance is 78, 28 points higher than the public’s, and is therefore of considerable note. High UAI scores reflect strong relationships with rigid codes of belief or behavior, are highly principled, and are intolerant of unorthodox behaviors and ideas. This score also reflects a lower tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity and an interest in planning for and controlling an unknown future;

- (2)

- This dimension had the smallest collected sample of statements of the 3, and the results of Hofstede’s findings were confirmed, with 77% of the 18 statements affirming this divergence. It should be noted that 14 of the 18 statements were from the municipality, showing a one-sided awareness of uncertainty avoidance, further affirming the findings. Of the 4 statements collected from transcripts of the public, there was a 50% split between affirmations and divergences. Statements such as, “The projects are important to control the impacts of climate change” (Municipal interview #1), “I don’t think they (residents) understand the real purpose of the site” (Municipal interview #2), and “our goal is to building resiliency into our infrastructure” (Municipal interview #1). A thematic analysis of this dimension proved challenging. While both the municipality and the public reported an interest in controlling risk and an unknown future, the municipality’s and the public’s perspectives diverged greatly. The municipality’s concerns were long-term macro-planning for climate change and environmental sustainability, while the public’s interests were child safety around the water. So, both groups referenced uncertainty avoidance, but the scale and scope proved difficult to account for;

- (3)

- Based on these findings, the following recommendations, drawn from Hofstede’s cultural theories, are applied specifically to the Trondheim case.

As an authoritative body:

- The municipality may alienate the public by not involving and educating residents about the purposes and uses of projects;

- The public may perceive the municipality as less knowledgeable than they are and question the municipality’s qualifications for executing strategic projects successfully.

In negotiating with the public:

- The municipality may come across as heavy-handed, which may cause the public to doubt whether they can be directly negotiated with;

- Engaging with the public may be undermined if negotiations are structured to such an extent that there is little flexibility to address unexpected issues;

- Public confidence may be undermined if the municipality does not emphasize its technical competence.

In communication with the public:

- The public may resist proposals and projects that have not allowed for public participation and active involvement;

- Public skepticism may increase if precise answers are not provided to all of their questions.

6.3. Masculine versus Feminine (MAS)

+21 points towards masculinity

- (1)

- With a MAS score of 8, Norway is considered the second-most feminine society in the world after Sweden [48]. Taking care of the environment is important, and Norway is a society that prioritizes caring for others and quality of life, with a focus on “working in order to live”. Equality and solidarity are highly valued, and it is important to make sure that everyone is included. Interaction through dialog is valued, and decision making is expected to be achieved through involvement. Conflicts can be perceived as threatening because they endanger the well-being of everyone; they are expected to be resolved by compromise and negotiation. The municipal score of 29 is 21 points higher than the general population and therefore of particular interest. The divergence indicates that the municipality is more achievement-oriented and assertive;

- (2)

- Finally, this dimension also had a strong correlation between the results of the survey and the thematic analysis of transcripts. The results of Hofstede’s findings were confirmed, with 83% of the 123 statements affirming this divergence. While 72% of statements suggested an awareness of feminine preferences, such as “It is important that the residents understand the solution” (Municipal interview #2), the majority of public statements (86%) confirmed the discrepancy. With statements such as “I just wonder what the municipality is planning, how do they want it here?” (Resident interview #14), “without discussions or guidance by the municipality, they did not feel confident to act on their own” (article 32). Perhaps most directly said, “the municipality is constantly trying to push their agenda through and won’t listen to what the people who live here want” (article 30). In the thematic analysis, the researchers became aware of the tendency for statements to be made that affirm expected social understanding and norms. There was a disconnect between the municipality’s MAS score, municipal statements, and statements collected from the public. Statements made by the municipality diverged from their MAS score 72% of the time, while statements made by the public confirmed the municipality’s MAS score 86% of the time. The collected statements for MAS were also disproportionately attributed to the public, accounting for 78% of the collection. This may reflect a lack of self-awareness on the part of the municipality in their own priorities and approach;

- (3)

- Based on these findings, the following recommendations, drawn from Hofstede’s cultural theories, are applied specifically to the Trondheim case.

As an authoritative body:

- The municipality may not like the expectations that the public has, e.g., involving them in all decisions that affect residents directly before taking such decisions;

- Municipal actors may feel limited in their ability to confront resistance “head on”;

- Presenting the municipal office’s prior accomplishments may not necessarily efficiently assure the public, as “one should not emphasize one’s personal successes”.

In negotiating with the public:

- Municipal actors may be upset by the blunt way the public expresses themselves;

- Municipal actors may be annoyed by the fact that the public seems to shy away from tackling conflicting demands head on;

- Municipal actors may feel disempowered by indirect negotiation tactics that residents might prefer.

In communication with the public:

- Municipal actors may be demotivated from rarely receiving positive feedback about their efforts and what they have accomplished;

- Residents may appear at first to be pushovers, as they seem to avoid conflicts and confrontations;

- The municipality should expect the public to keep a low-profile in public communications;

- Should municipal planners consider using the Hofstede cultural compass tool to inform the process of building consensus and public support?

6.4. Caveats to Current Application and Further Development

The findings drawn from this work have been generated and occur at the intersection of the data and the researcher’s interpretation of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions framework. The researcher’s role is one of personal involvement and empathetic understanding. It should be noted that in reflexive TA, there is flexibility and variability. The findings have been drawn from one coder and, while reflecting the values of a qualitative paradigm, must be classified as subjective and interpretive.

The Cultural Compass Tool is easily accessible and simple to use, allowing municipalities to gain greater insights into the priorities and perspectives of their constituents. The tool can also provide guidance in presentation, negotiation, and communication. Yet, despite these benefits, the Cultural Compass tool risks being used as simply another rubber stamp if municipalities are not properly guided in its applications and benefits.

Given these findings, the use of the Hofstede cultural compass should be recommended as a tool for municipalities, but with the caveat that further research should first be undertaken. In particular, the study of a large survey sample of residents could be compared to the national public scores, with the municipality providing even greater nuance. Additionally, a service provider may be required to properly administer the cultural compass tool as a service or to provide training to municipal actors to maximize its potential.

7. Conclusions

The survey shows that the biggest divergence between the public and the municipality lies in the long-term orientation of the municipality compared to the general population. The 39-point difference indicates a more pragmatic way of thinking in the municipal organization. Similarly, the municipality was found to diverge in terms of greater uncertainty avoidance and to exhibit a more masculine way of thinking. The scores of the protest group were not markedly different from those of the Norwegian public as catalogued by Hofstede (<10 points difference in every category). The literature review did not uncover any previous cases of SUDS conflict that could be directly compared to the present study. The use of thematic analysis in interviews and project documentation confirmed the findings of the cultural compass survey. The statements and interviews reinforce the findings that the discrepant philosophies between the residents and municipality cause some alienation on the part of the residents.

As an authoritative body, the municipality should consider these discrepancies when communicating and making decisions. An overall observation is that the municipality should be aware that locals may not approach subjects with the same mindset as municipal planners do. Plans should be made with room for flexibility to address the concerns of the residents, including on a conceptual level. Within the Nordic countries, positive public perception is integral to the timely acceptance and adoption of these climate adaptation measures. There is a need for greater understanding of what the expectations and perceptions of the public are. The Hofstede cultural compass tool is found to be a useful tool to quantify the cultural differences between the public and the municipality, but with some caveats. The subjective nature of thematic analysis may prove limiting in the evaluation of this tool, and it is recommended that the tool be first used by the municipality during project planning processes and that the greatest insights may best be found by a broader use of the cultural compass tool survey among municipal actors and the participation of localized public groups. Yet, much more must be carried out to understand the cultural codes that influence user perspectives and where breakdowns are occurring.

More research must be conducted to address the knowledge gaps uncovered by the present study. Future work should seek to determine best practices for application and better define the scope of use that the Hofstede cultural compass tool can provide in improving understanding of cultural expectations and how these can inform the planning of SUDS sites. Future work should be conducted in decision-making, planning, and design of SUDS projects at the local level. The application of the Hofstede cultural compass tool at the front end of the project processes may be the most beneficial to creating positive engagement, dialog, and better execution of SUDS at the local level.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.T.; methodology, B.T.; formal analysis, B.T. and E.A.; investigation, B.T.; data curation, B.T.; writing—original draft preparation, B.T. and E.A.; writing—review and editing, B.T., E.A., and T.K.; visualization, B.T.; supervision, R.A.B. and T.K.; project administration, T.K.; funding acquisition, T.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Research Council of Norway, grant number 237859.

Data Availability Statement

Interview and survey data are unavailable due to privacy restrictions as mandated by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data—the national institution for research standards and ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Pachauri, R.K.; Allen, M.R.; Barros, V.R.; Broome, J.; Cramer, W.; Christ, R.; Church, J.A.; Clarke, L.; Dahe, Q.; Dasgupta, P. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen, G.S.; Mydske, P.K.; Dahle, E. Multi-level coordination of climate change adaptation: By national hierarchical steering or by regional network governance? Local Environ. 2013, 18, 869–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssen-Bauer, I.; Førland, E.J.; Haddeland, I.; Hisdal, H.; Mayer, S.; Nesje, A.; Nilsen, J.E.Ø.; Sandven, S.; Sandø, A.B.; Sorteberg, A.; et al. Klima i Norge 2100—Kunnskapsgrunnlag for Klimatilpasning Oppdatert i 2015; Norwegian Environmental Agency/Norwegian Climate Service Center: Oslo, Norway, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wilby, R.L. A review of climate change impacts on the built environment. Built Environ. 2007, 33, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almås, A.-J.; Lisø, K.R.; Hygen, H.O.; Øyen, C.F.; Thue, J.V. An approach to impact assessments of buildings in a changing climate. Build. Res. Inf. 2011, 39, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RIF Norges Tilstand [RIF Norway State of the Nation]; Rådgivende Ingeniørers Forening [Consulting Engineers’ Association]: Oslo, Norway, 2021.

- Stortinget. Klimatilpasning i Norge [Climate Adaptation in Norway]; Klima- og Miljødepartementet [Ministry of Climate and Environment]: Oslo, Norway, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rambøll. Følgeevaluering av Framtidens Byer—Sluttrapport; Rambøll Management Consulting: Oslo, Norway, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen, V.; Lier, J.A.; Bjerkholt, J.T.; Lindholm, O.G. Analysing urban floods and combined sewer overflows in a changing climate. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2011, 2, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, H.; Du, G.; Zhou, J. Urban flood risk warning under rapid urbanization. Environ. Res. 2015, 139, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, S.; Völker, J. Water Framework Directive—The Way Towards Healthy Waters. Results of the German River Basin Management Plans 2009; Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety; Federal Ministry for the Environment: Bonn, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Environment. The EU Water Framework Directive; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2014; ISBN 978-92-79-36449-5. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The Forms and Functions of Green Infrastructure. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/ecosystems/benefits/index_en.htm (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Burkhard, R.; Deletic, A.; Craig, A. Techniques for water and wastewater management: A review of techniques and their integration in planning. Urban Water 2000, 2, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braskerud, B.C.; Paus, K.H.; Ekle, A. Anlegging av regnbed. En billedkavalkade over 4 anlagte regnbed. NVE Rapp. 2013, 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Muthanna, T.M.; Sivertsen, E.; Kliewer, D.; Jotta, L. Coupling field observations and Geographical Information System (GIS)-based analysis for improved Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SUDS) performance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, T.D.; Shuster, W.; Hunt, W.F.; Ashley, R.; Butler, D.; Arthur, S.; Trowsdale, S.; Barraud, S.; Semadeni-Davies, A.; Bertrand-Krajewski, J.-L.; et al. SUDS, LID, BMPs, WSUD and more—The evolution and application of terminology surrounding urban drainage. Urban Water J. 2015, 12, 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, P.G.; Ignatieva, M.; Granvik, M.; Hedfors, P. Green-Blue Infrastructure in Urban-Rural Landscapes-Introducing Resilient Citylands. NA 2014, 25, 11–37. [Google Scholar]

- Miljøforvaltningen, K.K.T. Cph 2025 Climate Plan: A Green, Smart and Carbon Neutral City; The Technical and Environmental Administration: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.; Geisendorf, S. Are Neighborhood-level SUDS Worth it? An Assessment of the Economic Value of Sustainable Urban Drainage System Scenarios Using Cost-Benefit Analyses. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 158, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, G.; Lamond, J.E.; Morzillo, A.T.; Matsler, A.M.; Chan, F.K.S. Delivering Green Streets: An exploration of changing perceptions and behaviours over time around bioswales in Portland, Oregon. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2018, 11, S973–S985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Mager, C.; Schmidt, N.; Kiese, N.; Growe, A. Conflicts about Urban Green Spaces in Metropolitan Areas under Conditions of Climate Change: A Multidisciplinary Analysis of Stakeholders’ Perceptions of Planning Processes. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassmusen, R.; Sæther, J.E. Fredlydalen Velforening. Available online: http://fredlydalen.synology.me/fdv/Blaklibekken/ (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Sand, S. Skittfiske, Bokstavelig Talt; Adresseavisen: Trondheim, Norway, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Thanem, T. Fortviler over Det Forfalte Friområdet i Trondheim: Det ser Ikke ut Her; Adresseavisen: Trondheim, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Thodesen, B.; Time, B.; Kvande, T. Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems: Themes of Public Perception—A Case Study. Land 2022, 11, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.B.; Levin, P.S. Mental Models for Assessing Impacts of Stormwater on Urban Social–Ecological Systems. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannforskriften. Forskrift om Rammer for Vannforvaltningen [Norwegian Regulations on Frameworks for Water Management]; Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment: Oslo, Norway, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vasseljen, S.; Haug, L.; Ødegård, I.M.; Knotten, V.; Zaccariotto, G. Overvann Som Ressurs. Økt Bruk av Overvann Som Miljøskapende Element i Byer og Tettsteder [Stormwater as a Resource. Increased Use of Stormwater as Environmentally Creating Element in Urban Areas]; Asplan Viak AS, NMBU: Ås, Norway, 2016; pp. 136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Øyen, C.F.; Mellegård, S.E.; Bøhlerengen, T.; Almås, A.-J.; Groven, K.; Aall, C. Bygninger og Infrastruktur-Sårbarhet og Tilpasningsevne til Klimaendringer; SINTEF FAG, Byggforsk: Oslo, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hauge, Å.L.; Almås, A.-J.; Flyen, C.; Stoknes, P.E.; Lohne, J. User guides for the climate adaptation of buildings and infrastructure in Norway–Characteristics and impact. Clim. Serv. 2017, 6, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambøll; Kaupang, A. Gode Grep for å Løse Fremtidens Kommunaltekniske Oppgaver [Effective Approaches to solving Future Municipal Engineering Tasks]; Technical Report; Rambøll Norway: Oslo, Norway, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Armento, S.; Guldhagen, J.F.; Åstebøl, S.O. Ny bydel Fagerheim i Haugesund. Hvordan overvann og blågrønne tiltak er ivaretatt i planleggingen [New district Fagerheim in Haugesund. How surface water and blue-green measures are taken care of in the planning]. In Proceedings of the Blå-Grønne Verdier Vårt Ansvar, Gardermoen, Norway, 6–7 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, R.H. Grøn Klimatilpasning: Udvikling af Københavns Grønne Struktur Gennem Klimatilpasning. [Green Climate Adaptation: Development of Copenhagen’s Green Structure through Climate Adaptation]; Teknik- og Miljøforvaltningen: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Minkov, M.; Hofstede, G. The evolution of Hofstede’s doctrine. Cross Cult. Manag. Int. J. 2011, 18, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2011, 2, 2307-0919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thodesen, B.; Andenæs, E.; Kvande, T. Mapping municipal-public conflicts over brook restorations—Lessons learned from a case study in Norway. To be submitted.

- Trondheim Municipality Befolkningsstatistikk. Available online: https://www.trondheim.kommune.no/aktuelt/om-kommunen/statistikk/befolkningsstatistikk/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- RIF Engineers. State of the Nation—Norges Tilstand 2021; Norwegian Consulting Engineers’ Association: Oslo, Norway, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kilnes, C. Her Renner Dritten Fritt. Adressa.No 2011. Available online: https://www.adressa.no/nyheter/trondheim/i/Po9vmJ/her-renner-dritten-fritt (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Multiconsult. Forstudie for Åpning av Fredlybekken; Trondheim Municipality: Trondheim, Norway, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rassmusen, R.; Sæther, J.E. Om Fredlydalen Velforening. Available online: http://fredlydalen.synology.me/fdv/OmVelforeningen (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Clayton, S.; Devine-Wright, P.; Swim, J.; Bonnes, M.; Steg, L.; Whitmarsh, L.; Carrico, A. Expanding the role for psychology in addressing environmental challenges. Am. Psychol. 2016, 71, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.S.; Clayton, S.; Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Capstick, S.; Whitmarsh, L. How psychology can help limit climate change. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A.R.; Schuldt, J.P.; Romero-Canyas, R. Social climate science: A new vista for psychological science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 11, 632–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracy, K. Discourse analysis in communication. In The Handbook of Discourse Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 725–749. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S.; Brinkmann, S. Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research; Sage: Newcastle, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede Insights Compare Countries. Available online: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/fi/product/compare-countries/ (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Wohlin, C. Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering—EASE’14, London, UK, 13–14 May 2014; ACM Press: London, UK, 2014; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Newcastle, UK, 2009; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede Insights Organisational Culture Consulting. Available online: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/ (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage: Newcastle, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V.; Hayfield, N. Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, M.; Delahunt, B. Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. All Irel. J. High. Educ. 2017, 9, 3351. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J.; Barclay, N. Social Barriers and the Hiatus from Successful Green Stormwater Infrastructure Implementation across the US. Hydrology 2021, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Nassauer, J. Community experiences of landscape-based stormwater management practices: A review. Ambio 2022, 51, 1837–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everett, G.; Adekola, O.; Lamond, J. Developing a blue-green infrastructure (BGI) community engagement framework template. Urban Des. Int. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassauer, J.I.; Kosek, S.E.; Corry, R.C. Meeting Public Expectations with Ecological Innovation in Riparian Landscapes. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2001, 37, 1439–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamond, J.; Everett, G. Sustainable Blue-Green Infrastructure: A social practice approach to understanding community preferences and stewardship. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 191, 103639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ureta, J.; Motallebi, M.; Scaroni, A.E.; Lovelace, S.; Ureta, J.C. Understanding the public’s behavior in adopting green stormwater infrastructure. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 69, 102815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamond, J.; Everett, G. Willing to have, willing to help, or ready to own—Determinants of variants of stewardship social practices around Blue-Green Infrastructure in dense urban communities. Front. Water 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, M.; Koburger, A.; Dolowitz, D.P.; Medearis, D.; Nickel, D.; Shuster, W. Perspectives on the Use of Green Infrastructure for Stormwater Management in Cleveland and Milwaukee. Environ. Manag. 2013, 51, 1093–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnthamrongkul, W.; Mozingo, L.A. Toward sustainable stormwater management: Understanding public appreciation and recognition of urban Low Impact Development (LID) in the San Francisco Bay Area. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 300, 113716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junker, B.; Buchecker, M. Aesthetic preferences versus ecological objectives in river restorations. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 85, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, E.; Maskrey, S.; Everett, G.; Lamond, J. Developing the implicit association test to uncover hidden preferences for sustainable drainage systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2020, 378, 20190207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazzard, M.; Booth, C.A. Perceptions of Teletubbyland: Public Opinions of SuDS Devices Installed at Eco-designed Motorway Service Areas. In Proceedings of the Sustainable Ecological Engineering Design, Ipswich, UK, 11–12 September 2019; Scott, L., Dastbaz, M., Gorse, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.B.; Jose, R.; Moobela, C.; Hutchinson, D.J.; Wise, R.; Gaterell, M. Residents’ perceptions of sustainable drainage systems as highly functional blue green infrastructure. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 190, 103610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvie, J.; Arthur, S.; Beevers, L. Valuing Multiple Benefits, and the Public Perception of SUDS Ponds. Water 2017, 9, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanifard, H.; Morgan, E.A.; Hadwen, W.L. Community Perceptions and Knowledge of Modern Stormwater Treatment Assets. Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien, N.R.P.; Arthur, S.; McLoughlin, M.J. Valuing amenity: Public perceptions of sustainable drainage systems ponds. Water Environ. J. 2012, 26, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede Insights. How to Read [The Cultural Compass] Report; Hofstede Cultural Compass Survey User Guide; Hofstede Insights: Helsinki, Finland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).