Not All Social Capital Is Equal: Conceptualizing Social Capital Differences in Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction and Theoretical Background

2. Research Approach

- The results of the study provide generalizable evidence about SC that exist in relation to different social groups.

- The article was published in a peer-reviewed journal.

3. Designing a Framework to Study Social Capital Differences

3.1. Social Capital Functions

3.2. Social Capital Resources

3.3. Negative Functions of Social Capital

3.4. Social Capital Needs

4. Social Capital Differences between Two Groups in Urban Areas

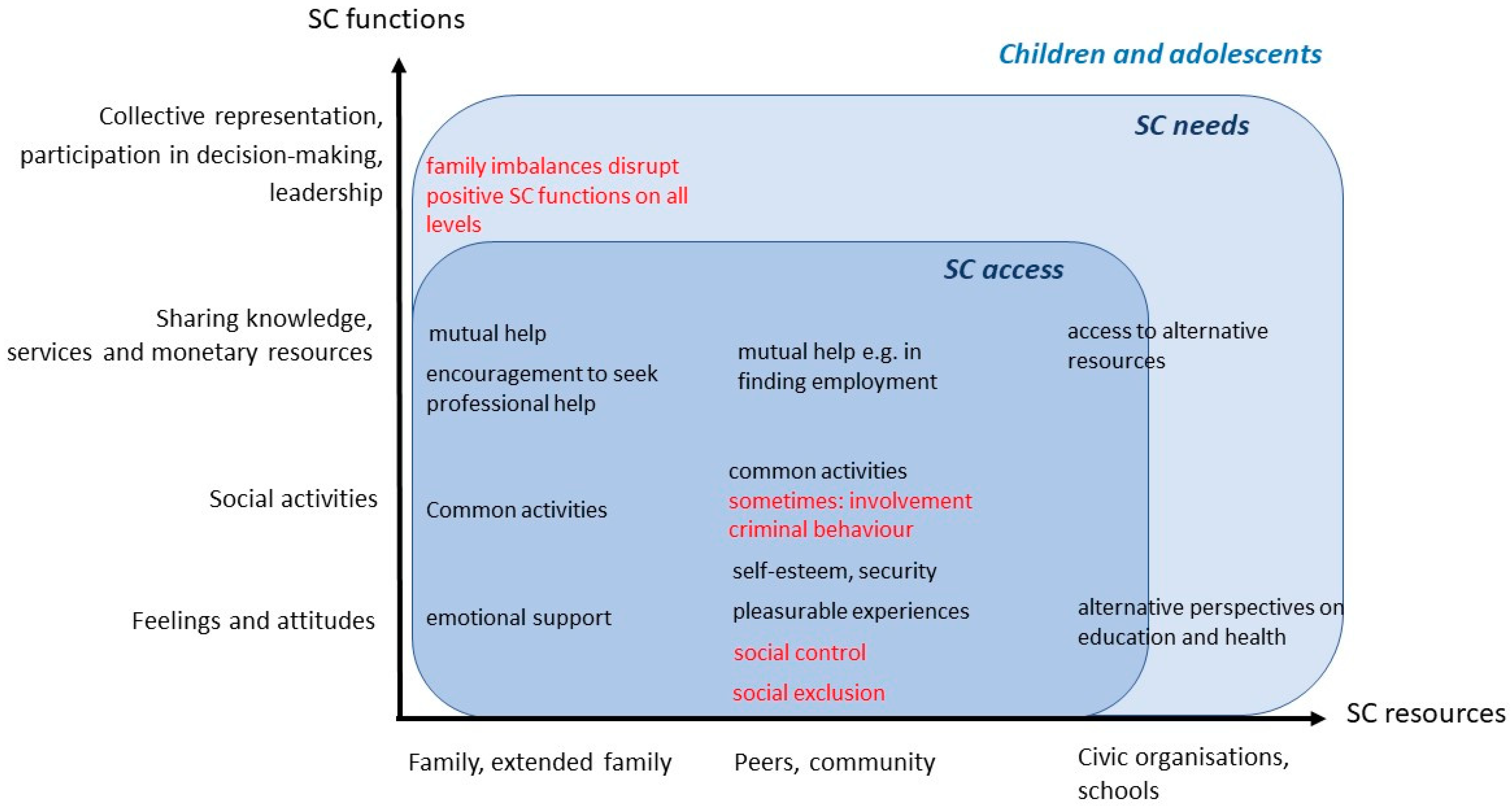

4.1. Children and Adolescents

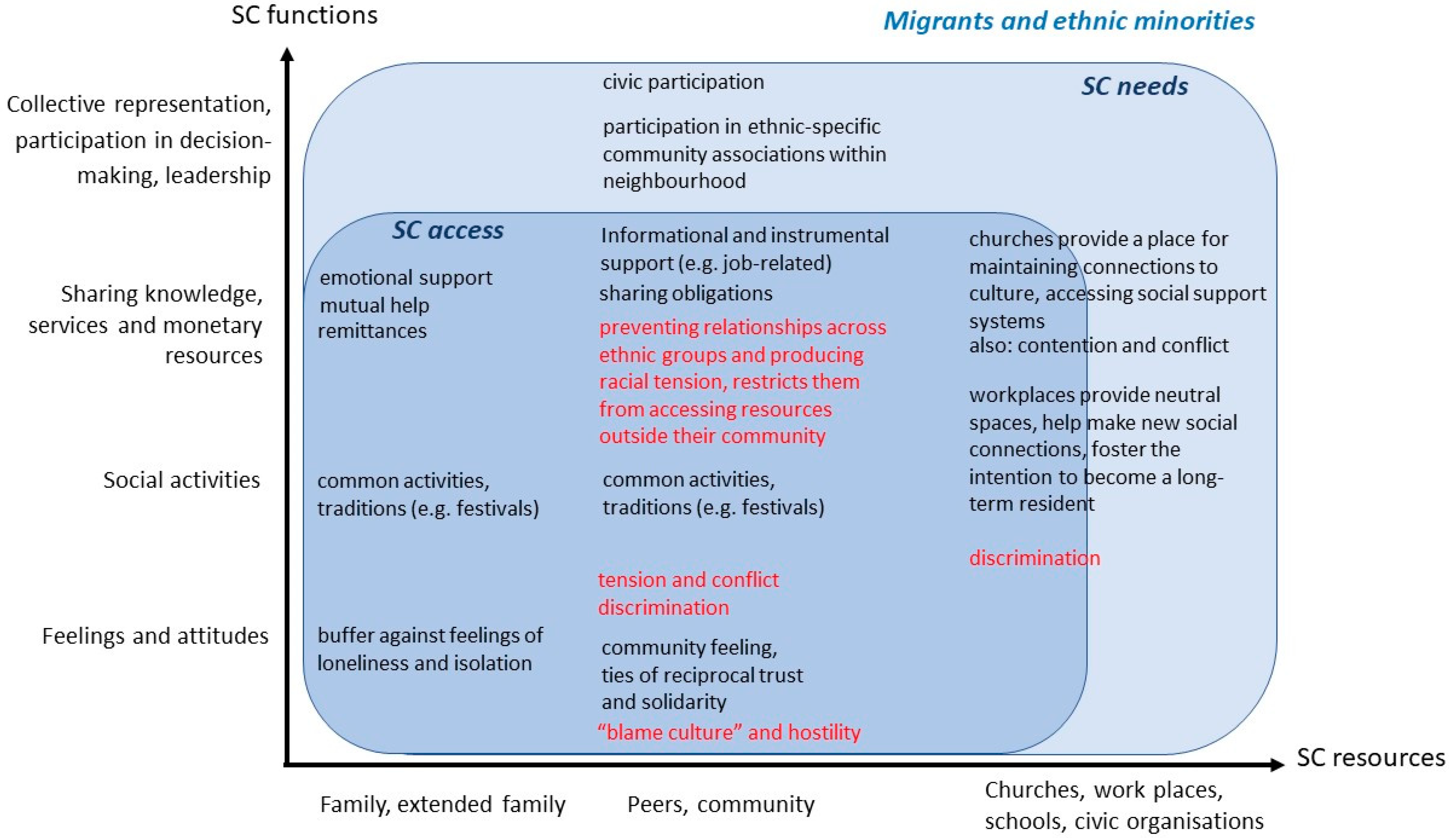

4.2. Migrants and Ethnic Minorities

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foster, S.R. The city as an ecological space: Social capital and urban land use. Notre Dame Law Rev. 2006, 82, 527–582. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.J.; Rehnberg, C.; Meng, Q.Y. How are individual-level social capital and poverty associated with health equity? A study from two Chinese cities. Int. J. Equity Health 2009, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adger, W.N. Social Capital, Collective Action, and Adaptation to Climate Change. Econ. Geogr. 2003, 79, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östh, J.; Dolciotti, M.; Reggiani, A.; Nijkamp, P. Social Capital, Resilience and Accessibility in Urban Systems: A Study on Sweden. Netw. Spat. Econ. 2018, 18, 313–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaso, P. Network topologies as collective social capital in cities and regions. A critical review of empirical studies. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.J. Family management and child development: Insights from social disorganization theory. In Facts, Frameworks, and Forecasts; Advances in criminological theory; McCord, J., Ed.; Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1992; pp. 63–93. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bertotti, M.; Harden, A.; Renton, A.; Sheridan, K. The contribution of a social enterprise to the building of social capital in a disadvantaged urban area of London. Community Dev. J. 2012, 47, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, P.R. Urban-rural differences in helping friends and family members. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1993, 56, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearrow, M.; Sander, J.; Jones, J. Comparing Communities: The Cultural Characteristics of Ethnic Social capital. Educ. Urban Soc. 2019, 51, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caughy, M.O.; Nettles, S.M.; O’Campo, P.J.; Lohrfink, K.F. Neighborhood matters: Racial socialization of African American children. Child Dev. 2006, 77, 1220–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernier, Q.; Meinzen-Dick, R. Resilience and Social Capital; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, K.S. Social Capital and Inequality: The significance of Social connections. In Handbook of the Social Psychology of Inequality; McLeod, J.D., Lawler, E.J., Schwalbe, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootaert, C. Social capital, household welfare and poverty in Indonesia. In World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 2148; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gittell, R.; Vidal, A. Community Organizing—Building Social Capital as a Development Strategy; Sage: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Vervisch, T.G.A.; Vlassenroot, K.; Braekman, J. Livelihoods, power, and food security: Adaptation of SC portfolios in protracted crises—Case study Burundi. Disasters 2013, 37, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs de Souza, X. Brown kids in white suburbs: Housing mobility and the multiple faces of SC. Hous. Policy Debate 1998, 9, 177–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M.S. The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Falco, S.; Bulte, E.A. Dark Side of Social Capital? Kinship, Consumption, and Savings. J. Dev. Stud. 2011, 47, 1128–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N. A network theory of social capital. In The Handbook of Social Capital; Castiglione, D., Van Deth, J.W., Wolleb, G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 50–69. [Google Scholar]

- Rezeanu, C.I.; Briciu, A.; Briciu, V.; Repanovici, A.; Coman, C. The Influence of Urbanism and Information Consumption on Political Dimensions of SC: Exploratory Study of the Localities Adjacent to the Core City from Brasov Metropolitan Area, Romania. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0144485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szreter, S.; Woolcock, M. Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 33, 650–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.; Amato, P. A taxonomy of helping: A multidimensional scaling approach. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1980, 43, 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, L.J.; Schmid, A.A.; Siles, M.E. Is Social Capital Really Capital? Review of Social Economy; Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: Abingdon, UK, 2002; Volume 60, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook for Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J.G., Ed.; Greenwood: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, B.D.; Astone, N.; Blum, R.W.; Jejeebhoy, S.; Delany-Moretlwe, S.; Brahmbhatt, H.; Olumide, A.; Wang, Z.L. Social Capital and Vulnerable Urban Youth in Five Global Cities. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 55, S21–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.P.; Daniere, A.G.; Takahashi, L.M. Social Capital and trust in south-east Asian cities. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 853–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atri, S.B.; Hagh MH, S.; Jafarabadi, M.A.; Feizi, A.; Ahmadi, Z. Relationship between Social Capital and lifestyle among older adults. Educ. Gerontol. 2018, 44, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Chakrapani, V.; Vijin, P.P. Validity and reliability of an adapted social capital scale among Indian adults. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1593572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldas, S.J.; Cornigans, L. Race/Ethnicity and Social Capital Among Middle- and Upper-Middle-Class Elementary School Families: A Structural Equation Model. Sch. Community J. 2015, 25, 137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ilan, J. Street Social Capital in the liquid city. Ethnography 2013, 14, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, G. Global Contexts, Social Capital, and Acculturative Stress: Experiences of Indian Immigrant Men in New York City. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2011, 13, 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokouchi, H. Proposal and Practice of Comprehensive Disaster Mitigation Depending on Communities in Preservation Districts for Traditional Buildings. J. Disaster Res. 2015, 10, 857–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saegert, S.; Winkel, G.; Swartz, C. Social capital and crime in New York City’s low-income housing. Hous. Policy Debate 2002, 13, 189–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Yang, S.J.; Liu, X.; Ren, X.H.; Liu, D.P.; Li, N.X. Association between SC and quality of life among urban residents in less developed cities of western China. Medicine 2018, 97, e9656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Duran, J.J.; Gregorio-Dominguez, M.M.; Sanz, M.M. Social Capital of poor households in Mexico City. Trimest. Económico 2012, 79, 905–928. [Google Scholar]

- Madhavan, S.; Landau, L.B. Bridges to Nowhere: Hosts, Migrants, and the Chimera of Social Capital in Three African Cities. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2011, 37, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karner, C.; Parker, D. Religion versus Rubbish: Deprivation and Social Capital in Inner-City Birmingham. Soc. Compass 2008, 55, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, T. Them and Us: ‘Black Neighbourhoods’ as a SC Resource among Black Youths Living in Inner-city London. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, P.M. Generating social capital for bridging ethnic divisions in the Balkans: Case studies of two Bosniak cities. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2006, 29, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, P.R. Helping-behavior in urban and rural environments—Field studies based on a taxonomic organization of helping episodes. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 45, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, C.E. Young People with No Ties. The Role of Intermediate Structures in a Disadvantaged Area. Rev. Española De Investig. Sociológicas 2015, 150, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, R.M. Vying for the urban poor: Charitable organizations, faith-based social capital, and racial reconciliation in a deep south city. Sociol. Inq. 2002, 72, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstrom, M.; Merlo, J.; Ostergren, P.O. Individual and neighbourhood determinants of social participation and social capital: A multilevel analysis of the city of Malmo, Sweden. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 54, 1779–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, E. Social capital and community strategies: Neighbourhood development in Guatemala City. Dev. Change 2001, 32, 975–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lu, C.L. Social capital in urban China: Attitudinal and behavioral effects on grassroots self-government. Soc. Sci. Q. 2007, 88, 422–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlton, S.; Vallance, S. The Commons of the Tragedy: Temporary Use and SC in Christchurch’s Earthquake-Damaged Central City. Soc. Forces 2017, 96, 831–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpatrick, S.; Johnson, L.; King, T.J.; Jackson, R.; Jatrana, S. Making connections in a regional city: SC and the primary social contract. J. Sociol. 2015, 51, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, E.M.; Weininger, E.B.; Lareau, A. From social ties to social capital: Class differences in the relations between schools and parent networks. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2003, 40, 319–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniere, A.; Takahashi, L.; Naranong, A. Social capital and urban environments in Southeast Asia: Lessons from settlements in Bangkok and Ho Chi Minh City. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2005, 27, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/339/bmj.b2700 (accessed on 2 October 2018). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenk, L.; Sentse, M.; Lenkens, M.; Engbersen, G.; van de Mheen, D.; Nagelhout, G.E.; Severiens, S. At-risk youths’ self-sufficiency: The role of SC and help-seeking orientation. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 91, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.; Maloney, W.; Stoker, G. Building social capital in city politics: Scope and limitations at the inter-organisational level. Political Stud. 2004, 52, 508–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A. Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology, 1998. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalonga-Olives, E.; Kawachi, I. The dark side of social capital: A systematic review of the negative health effects of social capital. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 194, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, K.G.; Hodgkinson, G.P.; Kalyanaram, G.; Nair, S.R. The negative effects of social capital in organizations: A review and extension. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 97–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, J.D.; Schwalbe, M.; Lawler, E.J. (Eds.) Introduction. In Handbook of the Social Psychology of Inequality; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortes, M. Kinship and the Social Order: The Legacy of Lewis Henry Morgan; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, J.; Adger, W.N.; Lorenzoni, I.; Abrahamson, V.; Raine, R. Social capital, individual responses to heat waves and climate change adaptation: An empirical study of two UK cities. Glob. Environ. Change-Hum. Policy Dimens. 2010, 20, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arneil, B. Diverse Communities: The Problem With Social Capital; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hofferth, S.L.; Iceland, J. Social capital in rural and urban communities 1. Rural. Sociol. 1998, 63, 574–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S. Social capital, local networks and community development. In Urban Livelihoods; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 156–173. [Google Scholar]

- Hegtvedt, K.A.; Isom, D. Inequality: A matter of justice? In Handbook of the Social Psychology of Inequality; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 65–94. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, P. Social capital and poverty: A microeconomic perspective. In The Role of Social Capital in Development: An Empirical Assessment; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Sidhu, A.; Beacom, A.M.; Valente, T. Social Network Theory. In The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects; Rössler, P., Hoffner, C.A., van Zoonen, L., Eds.; JohnWiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- von Otter, C.; Stenberg, S.-Å. Social capital, human capital and parent–child relation quality: Interacting for children’s educational achievement? Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2014, 36, 996–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Coster, S.; Heimer, K.; Wittrock, S.M. Neighborhood Disadvantage, Social Capital, Street Context, and Youth Violence. Sociol. Q. 2006, 47, 723–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furstenberg, F.F., Jr.; Hughes, M.E. Social capital and successful development among at-risk youth. J. Marriage Fam. 1995, 57, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedge, J.M.; Sianko, N.; Mcdonell, J.R. Professional Help-Seeking for Adolescent Dating Violence in the Rural South: The Role of Social Support and Informal Help-Seeking. Violence Against Women 2017, 23, 1442–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposa, E.B.; Erickson, L.D.; Hagler, M.; Rhodes, J.E. How economic disadvantage affects the availability and nature of mentoring relationships during the transition to adulthood. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2018, 61, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N. Inequality in Social Capital. Contemp. Sociol. 2000, 29, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Performance and Innovation Unit. Social Capital, a Discussion Paper; Performance and Innovation Unit: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, A. Social capital, the social economy and community development. Community Dev. J. 2005, 41, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, M. Black Social Capital: The Politics of School Reform in Baltimore: 1986–1998; University Press of Kansas: Lawrence, KS, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Small, M.L. Culture, cohorts, and social organization theory: Understanding local participation in a Latino housing project. Am. J. Sociol. 2002, 108, 345649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, E.A.; Junges, J.R.; Olinto, M.T.A.; Machado, P.S.; Pattussi, M.P. Violência urbana e capital social em uma cidade no Sul do Brasil: Um estudo quantitativo e qualitativo. Rev. Panam. De Salud Pública 2010, 28, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W. Do health behaviors mediate the association between social capital and health? Prev. Med. 2006, 43, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seid, A.K. Social interactions, trust and risky alcohol consumption. Health Econ. Rev. 2016, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.A. Organizational Social Capital and Nonprofits. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2009, 38, 643–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Social Capital Functions | Examples from the Literature |

|---|---|

| Attitudes, lifestyles, feelings and norms | Generalized norms, togetherness, everyday sociability, volunteerism [29]; adoption of cultural norms [31]; reciprocity norms [32]; perceptions of mutual concern [32]; socially favorable environment [33]; prosocial norms [34]; community sentiment and cohesion [35] Trust/trustworthiness [9,11,27,28,29,32,35,36,37,38] Safety/security [10,31,35,38], e.g., feel safe walking after dark, allow someone in your home if their car breaks down, area has safe reputation [10] Life quality/value of life [28,35] Self-confidence/dignity [31], e.g., feel valued by society [10], satisfied with life meaning [10] Sense of belonging/identity [33,39]; community feels like home [10] Acceptance of differences [28]; tolerance for diversity [10], e.g., multiculturalism make things better, enjoying living among different lifestyles, feel free to disagree with others [10] |

| Social activities | Relationships or connections [10,28,29,35] Joint activities of common interest (e.g., batches, classes, spending time, playing sports) [36]; pleasurable/shared experiences [31]; meeting and interacting [8]; doing exercises [8], travel ([8], having a party [20]; interpersonal relationship network and neighborhood cohesion [38]; neighborhood connections such as visiting a neighbor or running into friends when in area, phone conversations with friends, talking to people, eating a meal with others, visiting family outside community ([10]; big gathering of relatives [10]; involvement in ethnic and cultural festivities [32] Membership in specific networks [31]; reciprocity; building networks [40] |

| Sharing knowledge and information | Providing guidance, advice and tangible assistance [52]); information flows [30,53] finding information if needed [10] |

| Giving/receiving material and monetary resources | Giving a donation [41]; generating disposable income [31]; sending money to help family members buy a house [32]; remittances [37] |

| Giving/receiving services | Social/reciprocal support [35,38,39]); mutual protection [39]; babysitting and child care, transportation, repairs to home or car, household tasks, advice or moral support, picking up fallen envelopes, helping a person who collapses and is injured on the sidewalk, correcting inaccurate directions which you have overheard being given to a stranger [41]; reading to children, engaging with children in educational and cultural activities, mutual aid, amassing SC and converting it into institutional support [30]; willingness to assist children in need [11]; cooperation [27] “Cushion the fall” [33]; emotional support [52]; help in emergency or when needed [10], e.g., asking for help with child or doing a favor for sick friend [10] Practical resources and coping strategies in the face of discrimination [39] Means of control [33]; social control [42] Access to work [33], volunteering and job opportunities [8] |

| Collective representation, participation in decision-making, leadership | Participation in local community [10]; social participation [28,38]; participation in neighborhood activities [35]; volunteering, attending an event, being a member of group, on a committee, community project, organizing a new service [10]; interaction in the neighborhood [11]; local solidarity [28]; social agency or proactivity, e.g., picking up trash in public [10]; participation in community services, community work [43]; participation in religiously based organizations [32], social participation in formal and informal groups in society [44]; in tenant association [34], in parent association [30], memberships in informal groups and networks [29]; voluntary work for within-group community organizations [32]; collective action found in civic engagement [30]“self-governance” of urban neighborhoods [1] Intervention in disputes and misbehavior, seek mediation for dispute [10]; willingness to intervene in acts of delinquency [11]; willingness to intervene in acts of child misbehavior [11]; help solve some community problems within residential community [8] Mobilization and political action, neighborhood development, mobilization through community organization [45]; informal links (including clientelistic relations) with powerful groups [45]; protest [45] |

| Social Capital Resources | Examples from the Literature | |

|---|---|---|

| Bonding capital | Kin/family | Family [8,10,28,32,33]; kin/relatives [9,26,31,35,38,52]; parent–child relationship [30,35]; transnational family networks [39]; primary social contacts [2] |

| Friends, neighbors, coworkers, community | Friends [9,10,31,35,38,46] Peers [26,31,32] Neighbors, local residents [1,9,10,26,29,34,35,37,46,47] neighborhood [11,39]; tenant associations, a building’s formal organization [33] (Local) community [10,32,35,36,39,47,48]; ethnic community [33]; community organizations [45] Workplace, coworkers, colleagues [9,28,35,40] Connections to others outside of the household Informal groups in society, e.g., study circle/course at place of work, other study circle/course [44]; parental networks [49]; parent–parent relationship [30]; regional and diaspora racial connections [39]; existence of and participation in community or local organizations [50] | |

| Bridging capital | Random people/strangers | Random people, strangers [29,41,47]; contacts between migrants and hosts [37]; residents of different neighborhoods [1] |

| Formal authorities and organizations | Charity, government [41]; school [26,30]; teachers, counselors, healthcare providers and other adults in their community [52]; key service providers [29]; networks/civil accociations [33]; formal organizations or networks [46]; civic organizations [40]) volunatary organizations, governmental bodies [53]; non-profit and faith-based organizations, governmental agencies [43]; meeting other organizations, theatre/cinema, arts exhibition, church, sports event, letter to editor of newspaper/journal, demonstration, night club/entertainment [44]; powerful groups [45]; external agencies and levels of government [50]; formal groups in societye.g., union meeting [44] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wesselow, M. Not All Social Capital Is Equal: Conceptualizing Social Capital Differences in Cities. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci7020049

Wesselow M. Not All Social Capital Is Equal: Conceptualizing Social Capital Differences in Cities. Urban Science. 2023; 7(2):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci7020049

Chicago/Turabian StyleWesselow, Maren. 2023. "Not All Social Capital Is Equal: Conceptualizing Social Capital Differences in Cities" Urban Science 7, no. 2: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci7020049

APA StyleWesselow, M. (2023). Not All Social Capital Is Equal: Conceptualizing Social Capital Differences in Cities. Urban Science, 7(2), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci7020049