Abstract

The significance of urban landscapes in the current era of concern for a sustainable built environment can never be overemphasized. The study explores the landscape features and typologies of some urban environments within Kano to understand the management effectiveness of urban landscapes in the Kano metropolitan area. At least two wards were purposively selected each from the eight metropolitan local government areas due to their urban landscape and land use. Focus group discussion (FGD) sessions were carried out through with prominent elders and “Masu Unguwanni” (village/ward heads) of each of the sampled wards as well as direct assessments of their physical characteristics to justify the general landscape progression in support of documentation for the present and future generation. The study unveils the layout typology, the scenic points and the ecological and cultural landscapes in the sampled districts. It further reveals that the historic urban forms in Kano are degrading with time, or rather not following the course of sustainability, as the physical surroundings satisfy the immediate needs of the communities. However, the study suggests increasing the awareness of Kano’s urban landscape preservation and the 2011 UNESCO proposal implementation on Historic Urban Landscapes (HUL). Then, the study discourages unhealthy developments within Kano Metropolis and the entire state. It also recommends landscape architects be part and parcel of planning schemes for controlling and regulating urban development via the formal practice of land allocation, land acquisition, building codes, design, planning and construction.

1. Introduction

In recent years, circumstances are changing as studies in Africa focus on urban landscape improvement and green network [1,2,3,4,5,6]. One of the commonalities of these studies is the assessment of the depletion states, effects and accessibility of the urban space using several approaches. A perception of cities in northern Nigeria exposed the challenging condition of green infrastructure in fast decline due to severe forces from the human influence index [7].

Nasidi [8] assessed environmental challenges that surface due to uncoordinated human influence (disturbance of open space, deforestation in Kano, Nigeria, and other cultural values) while Halima [9] analyzed the declining state of urban greenery in metropolitan Kano along with urban development as it disrupts ecological equilibrium with the rising invulnerability of land.

Moreover, most of the research on urban space in West African cities focused on a mundane protection approach that failed to harness adaptive schemes of the past or emerging landscape index approaches of recent times. Moreover, they cease to correlate the revolutionary practices of selected precincts to explore the principles that affect plot layout formation, processes and phenomena, and the summarizing typology of landscape values, and establish a comprehensive framework. This study attempts to fill this gap.

Kano was founded in the ninth century and its development and planning commenced around 1095–1134 [10,11]. As the third major city in Nigeria after Lagos and Ibadan, Kano is the administrative capital of Kano state. The demographic development of Kano was due to its suitable landscape, it being a mercantile city, its hospitality and accessibility [12]. The wet season starts in May and ends in September, with August being the rainy month in Kano. The yearly rainfall differs from 600 to 1200 mm. The mean yearly temperature fluctuates from 26 °C and 32 °C [13]. There is a slight disparity in temperature, compared to rainfall, but the mean temperature rate is usually colder throughout Harmattan season [14]. The Challawa and Jakara rivers remain the major waterways within the city catchment area. In contrast, the Kano river irrigation scheme, sited to the south and northeast of the ancient municipalities, supplies large areas of irrigated land. The city’s peri-urban environments are dominated by cultivation parklands, meadows and speckled trees with a quite low quantity of natural forested savannas [4,15].

1.1. Landscape-Based Approach

The word ‘landscape’ is broadly used. Besides common usage, it is used in many disciplines such as history, art, geography, archaeology, planning and architecture, to mention a few. There is also figurative usage—political landscape and linguistic landscape are such instances [6,16].In addition, “the study of historic urban landscapes alongside it typology originated by describing the fundamental character of metropolitan landscapes in the early development of city morphology within the profession of geography” [16]. “Urban typo-morphology begin to seize form as a structured field of knowledge at the end of the 19th century [16,17]. Several key extractions were in the work of German speaking geographers. Similarly, ref. [18] suggested,“a typology of the urban landscape as the object of research in architecture”.

To connect people to their housing environment, one should recognize that the physical environment we construct expresses our socio-economic values. Indeed, ref. [19] has also observed that the buildings that we produce and their layouts are a direct product of a balance between a culture and its environment.

Human shelter is a communal survival element that manifests in one way or another. From the very origin of civilization, humanity has been intensely affected and thus conditioned by its natural surroundings. Humanity protected itself in huts, caves, trees, etc., as was evidenced in primitive times. The class of a shelter or dwelling is relative or a matter of opinion. Humanity cannot flee the increasing effect that would ultimately affect its style and personality. “Architects or designers are in an insightful situation, which makes them appreciate their community and show conscientiousness to an individual client and to the contextual look and projection of the progression of life itself” [20].

“Urban fragments often characterize a distinctive population density, remarkable nature and metropolitan morphological characteristic. They provide the circumstance in which heritage assets are cited, but they must not be treated as simple in context, because it is often a group of objects and their context that generates value” [21].

“The preservation of surviving urban assets (urban concepts, structures, historic buildings and sites, evolutionary processes, or local traditions and practices) left to represent significance is called a landscape-based approach. One of the key aims of such a landscape-based approach is considering conservation as reducing the undesirable impacts of socio-economic progression on what is measured to be of importance, by incorporating heritage protection and urban development” [22,23,24].

The situation of cultural landscape management has been changing towards more all-inclusive methods, comprising ideas such as the intangible landscape in the context of sustainable urban development. In addition, the cultural landscape has been accompanied by a greater consideration of the economic and social function of ancient cities [22,25,26,27,28].

The historic urban landscape (HUL) approach guarantees that the shift towards a smart city progressive model based on precise local cultural resources is for technological improvement. In other words, the eco-city approach becomes culture-led as it kindles places as spatial “loci” for implementing circularization and synergy measures [29].

‘Gorna’ housing project designed by Hassan Fathty was built using traditional ideas and obtainable local resources with all the essential land uses incorporated. He [30] asserts that “tradition is not necessarily stagnant; it can be enhanced and preserved in Africa”.

According to [29], cultural heritage is a major constituent of the urban system: it ought to be perceived as a dynamic sub-system that progresses over time under the tension of many different forces, though still maintaining its uniqueness, reliability, and continuity. Assuming Geddes’ analysis, cultural heritage preservation and management should be considered via a dynamic perception, characterized by synergies, circular creativity and processes.

It is also noticeable that people can base their choice on an exceedingly broad range of potentials, and can transform an arid region or topographical level hills within broad limits to landscape and improve the natural surroundings. Kano Metropolis is not an exception and has undergone several transformations in urban landscape and typology [23,31]. Moreover, urban land can be described as the art and science of ordering the use of land for building positioning, commerce, communication, primary and public movement routes, manufacturing, sport, and recreation to attain the utmost possible economic ease, and landscaping for the planning of ideals [32,33,34].

1.2. Sustainability and Urban Landscape

Sustainability has been trending as a universal term to illustrate the progression that includes a variety of forms that the procedure may take [35]. The accessible definitions in the literature are in three categories [36] and they focus on these subjects: (i) preserving benefits attained through an early program, (ii) maintaining the program in an organization, and (iii) building the capacity of the benefiting public to maintain a program. Following this classification as a basis, ref. [36] defines sustainability as ‘the technique of ensuring an adaptive prevention scheme and a sustainable development to be incorporated into current operations to benefit various stakeholders”.

At first, the authors in [36] viewed sustainability as a transformative process with explicit sustainability acts pushed to reinforce organizational infrastructure and the inventive features necessary to uphold a particular innovation. Subsequently, ensuring an adaptive prevention scheme was seen as a form of sustainability practice. These schemes must be open to alteration, hence building a setting for innovations to adapt to the system, if compulsory, in which they are established. Thus, an assumption is that sufficient infrastructure is essential to sustainability.

As such, sustainable planning in the context of the metropolitan landscape remains an inclusive and elaborate interaction between urbanization, population increase, economic development, and the living environment [37]. Sustainable planning entails the running of those aspects that will support the continuation of the urban space for the inhabitants, to ensure the environment remains livable for the community [38].Moreover, there are sustainable aspects that will support the existence of a sustainable urban landscape [37] including having good (i) demographic and socio-economic settings; (ii) planning and appropriate management towards persuasive urban migrants; and (iii) planning by-laws and authorities. In this context, the public must know the value of an urban landscape to value the existence and need for urban forms and spaces.

1.3. Aim and Objections

The study explores the landscape features and typological assessment of some settings within urban Kano, intending to understand the effective management of urban landscapes in the Kano Metropolitan area. The specific objectives are

- i.

- To authenticate the historical establishment of some selected wards/districts within the Kano metropolis.

- ii.

- To verify the landscape assets and land-use typology of some sampled wards/districts within the Kano metropolis.

2. Materials and Methods

Metropolitan Kano is closely sited at the heart of Kano State (latitudes 11°52′ N and 12°07′ N and longitudes 8°24′ E and 8°38′ E). In 1820,the population was about 30 to 40 thousand [39]. It is in the semi-arid savannah zone and has distinctive wet and dry seasons [40]. It has an estimated population of over 10 million. Following the 2006 census, the population of Kano metropolis was about 2.2 million, which made it the second largest after Lagos [41], and it rose to more than 4 million in the subsequent census (NPC, 2009). It is also the trading hub of Northern Nigeria [42].

As a typological framework for the Kano metropolitan area, the study adopted a framework developed based on knowledge acquired from a literature review alongside the study objectives. The process entailed field observation/visual evaluation and focus group interviews/FGD that paved the way for research findings. This study adopted a two-stage qualitative approach using spatial analysis methods (inventory/direct assessment of the physical characteristics of the study area) and focus group discussion (FGD) sessions with eight custodians/prominent elders and 11 “Masu Unguwani” (ward heads) of some sampled wards. From April 2020 to November 2022, the authors performed field observations and collected spatial information. The first stage involved mapping urban forms/spaces and focus group interviews within the sampled wards, primarily starting with defining the context and identifiable attributes of urban landscapes and the layout of the area surrounding metropolitan Kano. Accordingly, the collected information from the urban spaces within the wards (such as literature, behaviors and maps) was in the form of recording techniques, in-depth interviews, sketch outlines and measurements. In this context, the essentials of the landscape form comprised both objective elements (including layout typology, structure and core) and subjective (such as spatial behaviors and boundary functions). It also involved a review of published documents (both online and printed) within the framework of the Kano region and urban landscape. With the nature of the urban disposition of Metropolitan Kano, several logical ways were utilized in the selection, sorting and ordering of the neighborhoods and locations.

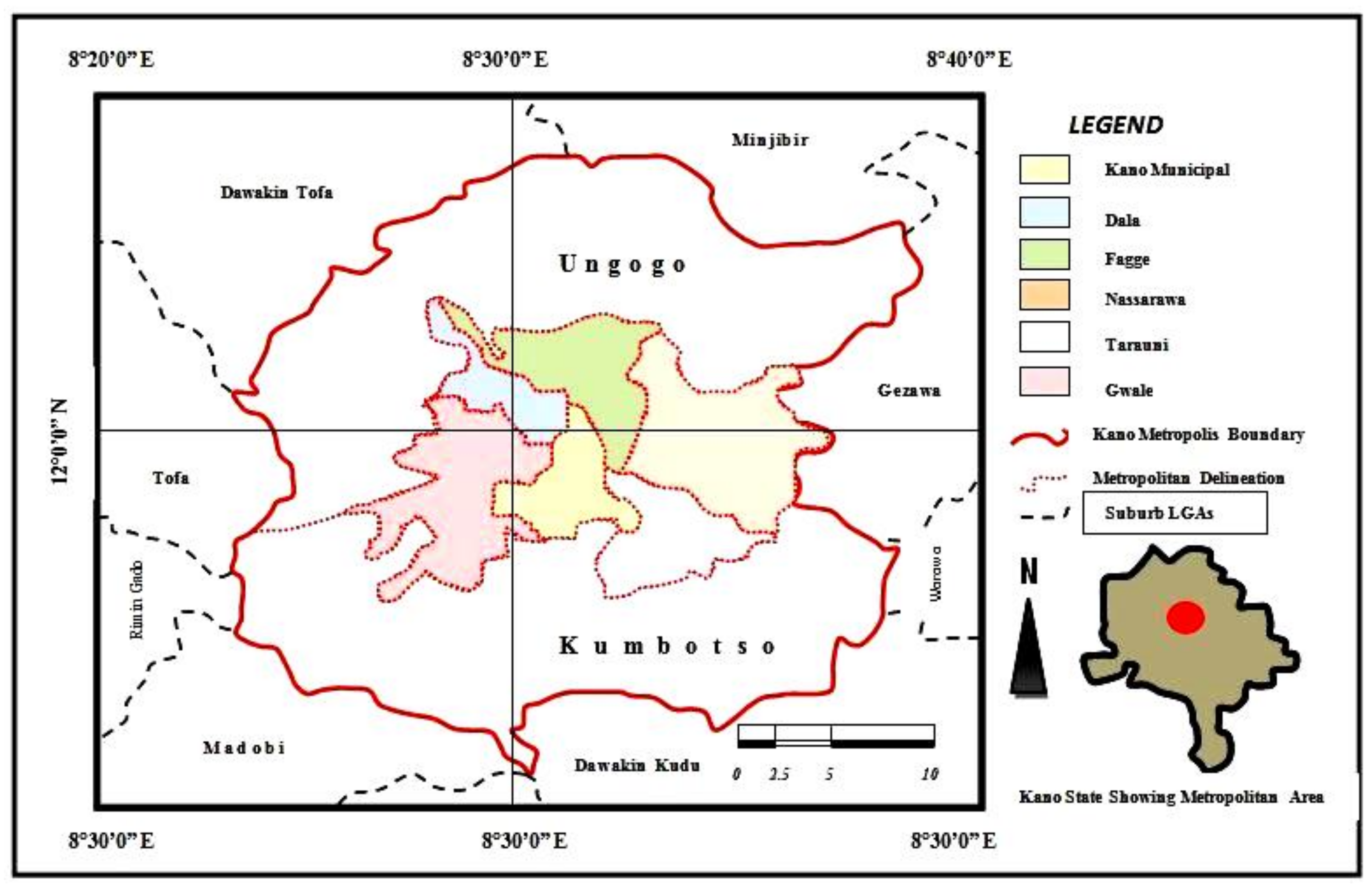

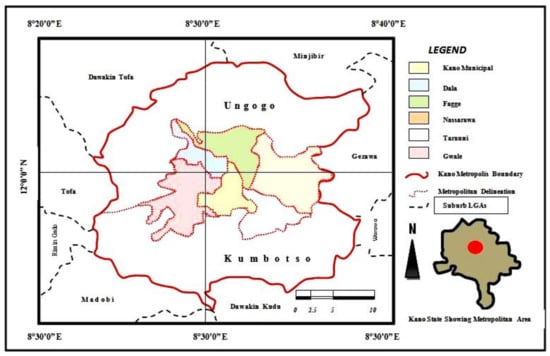

“The most prominent is the geographical boundaries (Figure 1), hence eight metropolitan local government areas (Dala, Fagge, Gwale, Kano Municipal, Kumbotso, Nassarawa, Tarauni, and Ungogo) are the case study locations for the study rather than the respective four (4) city sectors and the wards”. Ordering using local government areas was adopted as traditional administrative power is being transferred to the district head of each local government. Purposive and convenient sampling was used in the selection of the areas (wards) of study within the metropolis and focus group discussion (FGD) sessions, respectively. At least two wards were purposively selected from each local government area due to the availability of urban landscapes and massive transformation in such areas.

Figure 1.

Kano metropolitan map. Source: Authors, 2023.

3. Results

3.1. Theoretical Findings

Data were gathered by reviewing and analyzing (content analysis) documentation on the prominent wards within Kano Metropolis. This is presented in line with the first research objectives.

3.1.1. Kano Urban Patterns in Pre-Colonial, Colonial and Post-Colonial Period

Kano is similar to Zaria and Katsina in its pre-Islamic foundations, in its old walled Hausa–Fulani centers of administration, of trading and of crafts and its colonial development, although Kano was founded earlier than Zaria and has been a more important commercial as well administrative center in both colonial and independent Nigeria. It has been better described than any of the other northern Nigerian cities, starting with the Kano chronicles [43].

Before the actual founding of Kano City, several sites were sacred to the local inhabitants. Dala Hill, where an early iron smelting furnace has been traced to the 7th century [44], was the home of “Maguzawa” (Pagan Hausa).An important sacred tree was located on the site of the “Madabo” mosque in “Madabo” ward, just to the east of Dala Hill. There were sites where ceremonies were performed until the 19th century: The first was near the old palace at “Kofar Ruwa”; the second was the well of “Maiburgami”; and the third was a grove at “Bakin Ruwa”, located near Jakara, the low-lying ground west of the market [32]. These areas are near the core of the modern city of Kano.

The first city wall was built between 1095 and 1134 during the reign of the third Hausa king [15]. After the ceremonial slaughter of 100 cattle, the wall was started somewhere east of the market near Jakara stream, where it drains, and was constructed counterclockwise to include both the laterite-capped, residual hill of Dala and Goron Dutse. It was finally completed in about 1150. Sarki Muhammadu Rumfa, the Emir of Kano (1463–1499) extended the south eastern part of the walls to include a palace compound, and moved from the old pagan site east of Dala near “Kofar Ruwa” to the present location.

The introduction of colonial rule and administration came to Northern Nigeria from the south. In January 1900, the British protectorate of Northern Nigeria, proclaimed by Fredrick Lugard, was established after the military campaign of 1900–1904 [45]. This latter development still affected urban development and transformation sixty years later.

In Northern Nigeria, Sir Lugard found an organized system of Muslim emirates formed from former Hausa states as a result of the Fulani jihad, and states were administered by emirs through Shari’ah law by an “alkali” (judge). The introduction of the railway line brought life to the trade contacts with the Kano region. People also took advantage of good agricultural terrain for urban growth and a good water supply. Animal hides and skins, groundnut, cotton, ginger, and minerals were the main products exported from this railway infrastructure.

In 1917, Lugard, as governor general with the goal of amalgamation, created the township ordinance, which abandoned the use of the government station and cantonment and made use of township and urban district. The ordinance also classified the township into three, each with a different degree of municipal responsibility. The first category, the European reservation, comprised a colonial residential area, railway area and commercial area; the second, non-European reservation (Sabon Gari), consisted of a government clerks’ area, artisan and laborers’ area, railway area and market/trade spot; the third category included special areas (Tudun Wada), considered not as a township but including building free-zones, police stations, prisons, barracks/army lines, and fell-mongering plots. Each area eventually had to be planned according to the local circumstances and terrain. In any case, a “green belt” was always be retained in planning proposals to provide areas to be enclosed for recreation and artistic beauty and break urban monotony [46].

In this approach, land and plots were allocated and provided with sewage management, drainage, water, electricity, access roads and a range of individual and commune services. In addition, the aim was to include additions and improve services and facilities within the entire neighborhood. Meanwhile, the “squatters upgrade” was to convert the existing traditional housing stock, particularly in the serviceable areas in central locations where people could maintain their current access to their commercial routine, schools and work. What constituted the city of Kano and its environs was virtually encompassed by the city wall and was within an area of 17.5 square kilometers in the early 1900s when the colonial masters came [47,48].

The modern Kano metropolitan area constitutes two main areas, namely “Birni/Cikin Badala” (walled city), considered the inner-city, and Wajen Badala (outside city), the township. “Wajen Badala” settlements include several suburbs which follow the cardinal axis of the walled city. The oldest is the Fagge suburb, founded in the 12th century as a camping place for northern traders of the towns north of the Sahara, whereas the “Sabon Gari” suburb was established in 1914 to cater for the people that are mainly from the southern part of the country [49]. Other suburbs include “Tudun Wada” and “Dakata”, which serve as a squatter expansion of the aforementioned suburbs, although they have a blend of various ethnic groups, with Hausa as the predominant inhabitants [45], and the Nassarawa and Bompai suburbs situated to the east of the walled city, constituting the former colonial seat of government. Furthermore, the former villages of Gyadi-Gyadi, Hotoro, Hausawa and Naibawa are located to the southeast; Sheka, Dorayi and Sharada are to the southwest; and Kurna, Rijiyar Lemo and Ungogo are located to the north of the walled city. According to [14], this suburb area has two settlement patterns that entail an irregularly shaped traditional nucleated resident pattern with narrow streets and a contemporary nucleated pattern where houses are rectangular- or square-shaped and attached with wider roads.

Two decades of developmental plans were prepared by Trevallion in 1963 [50] and subsequently revised in 1976, 1980 and 1990 [10]; however, this 1990 preparation was disbanded due to a shortfall in enforcement as well as bureaucratic, technical, and financial concerns [10]. In 1963, the plan proposed spreading out to the southwest and designating potential road networks and neighborhoods [11]; this was partially executed. The urban landscape of Kano has gone through a range of transformations from the collection of traditional architecture to an Islamic style, and to the British colonists’ changes in landscape morphology as well as land development policies [51].

When combined, government policies and natural landscapes or traditions in the Hausa–Fulani background have resulted in a walled city, inspiring compound patterns, agricultural lands as well as the usual rocky hills. The typology expresses the idea of a triple open space or hub in traditional family residences that is similar to the model of cities bordered by a wall with a doorway and a city defense wall with a gateway.

3.1.2. The Evolution of Some Wards within Metropolitan Kano

Kano has ceased to be restrained by its wall in the urban plane because the old city became an entity by itself while Fagge, Gwagwarwa, Gyadi-Gyadi, Hausawa, Kurnar Asabe, Nasarawa, Na’ibawa, Sabon Gari, Tarauni and Tudun Wada all developed into discrete wards. This phenomenon (both anticipated and real growth) is the power of the manifestation of the Trevallion blueprint in 1963 with a vision to set a legislative structure that could guide, control and manage the growth of metropolitan Kano [26,31].

- (a)

- Ward delineation procedures

Having eight local government areas in the Kano metropolis, at least two wards were purposively selected from each local government area: Dala (Dala and Kofar-mazugal), Fagge (Fagge and Jabba), Gwale (Gwale and Dorayi/Kabuga), Kano Municipal (Sharada and Yakasai), Kumbotso (Challawa and Kumbotso), Nassarawa (Dakata Kawaji/Badawa and Hotoro), Tarauni (Babbangiji and Unguwa Uku) and Ungogo (Bachirawa and Ungogo).

The methods of data collection included focus group discussion (FGD) sessions with custodians, prominent elders, or “Mai Unguwa” (ward head) of each sample ward. It involved a review of published documents (both printed and online) in the context of the Kano region. With the nature of the urban disposition of metropolitan Kano, several logical ways were used in the selection, sorting and ordering of the neighborhoods and locations.

- (b)

- Description of the selected wards

Below is the historical establishment of the sampled wards, arranged alphabetically:

- i.

- Babbangiji ward is located in the Tarauni local government area, accessed via the “Massalacin Murtala” road southwest of Kano Metropolis. The Hausa/Fulani clans dominate the commune and other tribes from the northern part of Nigeria. They are mostly artisans, builders, carpenters, and small-scale traders as well low-income workers. There is no marketplace, but it has clinics, government primary schools, and secondary schools for boys and girls.

- ii.

- Bachirawa is situated in the Ungogo local government area, accessed via the Katsina road in the northern part of metropolitan Kano. Established in the 1980s and dominated by the Hausa/Fulani tribes, most people come from Katsina state and other tribes from the northern part of Nigeria. It consists of 75% contemporary Hausa residential structures and 25% modern buildings.

- iii.

- Challawa, located in Panshekara, in the Kumbotso local government area in the western part of the metropolitan areas. It was originally a Fulani settlement due to its closeness to river Challawa, and it had a rich soil suitable for farming and the rearing of animals. The town started developing in the early 1970s due to the institution of the Kano Water Works (WRECCA) and manufacturing industries. Various tribes from all parts of the country live there.

- iv.

- Dakata/Kawaji/Badawa is located in the Nassarawa local government area and accessed via the Yankaba/Hadejia road, in the northeastern part of Kano Metropolis. Dakata/Kawaji was established around the early 1950s and a few houses are built in mud and there are also modern building materials such as cement blocks, metal doors, and windows. On the other hand, Badawa was established in the late 1970s. It is an exemplary ghetto commune with 97% contemporary typologies.

- v.

- Dala is positioned in the Dala local government area and is a name given to one of the ancestors of the “Abagayawa”, known as the original indigenes of Kano. It has been associated with iron smelting and smithing, and the “Tsumburbura Shrine” [43,45]. Dala ward is a settlement at the bottom of a hill, with a gentle slope of about 2–3 mm in the east and south direction, and about 2 min the northern direction toward the Gwammaja Road, while due west, there is a deep and dirty water body of about 6–10 m depth.

- vi.

- Dorayi/Kabuga is located in the Gwale local government area and is accessed via the BUK road, almost at the center of the Kano metropolitan area. The majority of the residents of Rijiyar-Zaki, Dorayi, Kabuga housing estate, and Yamadawa residential areas are, by origin, indigenes of the old city of Kano, who for reasons of choice, city slum, improvement in economic status, and proximity to the place of work, among others, decided to relocate. While Dorayi is a progressive slum commune with 86% contemporary typologies, Kabuga remains a planned layout.

- vii.

- Fagge/Jabba is located in Fagge local government area. Fagge is almost in the center of Kano Metropolis and accessible from the Ibrahim Taiwo road. It is one of the initial areas laid out by the colonial masters in the later 1950s and is a predominantly non-indigenous settlement (absorbing Katsina and Niger immigrants). However, Jabba is accessed through the airport road due northeast of Kano Metropolis. It was founded around 1960 and was originally a resettlement scheme for residents or villagers in the area of the present Aminu Kano International Airport, but is now dominated by the Igbo business class and other ethnic groups from southern part of the country.

- viii.

- Hotoro is located partly in Tarauni and partly in Nassarawa local government area. It is accessible via the Maiduguri road and the eastern ring road by-pass due southeast of metropolitan Kano. Created around 1950 and initially under Ungogo District, it consists of three parts: Hotoro Kudu (South), Hotoro Arewa (North), and Hotoro Danmarke. It was later segregated into sub-units or wards headed by “Dagaci” and “Mai Unguwani”, with the respective ward heads now separated by the Maiduguri highway due south east of Kano Metropolis. Ref. [45] proclaims that the name Hotoro derived from Fulani, from the word “Hutu”, meaning rest. The area used to be the resting place for caravans and hunters (Fatake and Mafarauta) and used as a transit camp (Zango) under one famous well-known “Rijiyar Hagama”.

- ix.

- Kofar Mazugal is located in the Dala local government area, accessed via the Gwamaja/Mayanka road due south of Kano Metropolis. It originated in the 19th century when the area was predominantly dominated by blacksmiths who operated their trade there. The name was taken from a fire-blowing instrument used by the smiths. Blowing of fire continually emits the sound “Zugal-Zugal” which is why the area is called Mazugal [45]. As such, when the ancient wall surrounded Kano, a gate was opened at Mazugal, named “Kofar Mazugal”.

- x.

- Kumbotso remains in the Kumbotso local government area, and joined examples of traditional Hausa and Fulani communes. A modern settlement was purposely established for irrigation farmers from the Kumbotso River from 1977–1982, during Rimi’s administration. The topography remains similar to that of Panshekara, but in recent time it hosts educational institutes, industries, residential quarters, trade zones and farmland.

- xi.

- Sharada is situated in the Municipal local government area, accessible via the B.U.K road due south of Kano metropolitan area. It was established around the 1950s by Malam Aminu Kano, a leading politician in Kano politics. It has two sections and Sharada “Fegin Mayu” is occupied by more craftsmen and low-income earners than the industrial zone which was formally farmland.

- xii.

- Ungogo remains in the Ungogo local government are, accessible through the Katsina road northeast of the Kano Metropolitan area. It was established over 200 years ago as a Fulani cattle farm settlement, and around 1970, the then government sub-divided the farmland into housing layouts. Although in recent times, there is a lot of infill in the typology.

- xiii.

- Unguwa Uku is positioned in Tarauni local government area, accessible via the Zaria Road due southwest of Kano Metropolis. Historically, the name originated from three Fulani compound heads, namely Alu, Mohd, and Nono, surrounded by their farmland, for farming and rearing their animals. Each of them settled in different areas that produced the term “Rikuni Uku” (three provinces or villages), later called “Unguwa Uku” around 1970 [48]. It has one “Dagaci” (district head) and three ward heads (Masu Unguwani) and is dominated by low-income earners such as traders, craftsmen and workers.

- xiv.

- Yakasai remains among the three heads of pre-Islamic Hausa, alongside ‘Gwale’ and ‘Sheshe’, who came from the historic empire of Gaya, east of Kano [20]. The current ward has been relocated from an older ward since the region became a part of the city only after the 15th century extension of the city wall. At one time, Yakasai was the largest ward in the city, in terms of land and inhabitants; later, it was sub-divided into A and B wards [45]. In 1961, an added ward emerged, called Yakasai “Sabuwar Unguwa”, founded to provide relief in governance. During colonial times, its location, its relationship with the Mallam class, and its ability to take in immigrants made it a quarter preferred by the mid-level Native Authority civil servants.

3.2. Spatial Data

Quantitative and qualitative data were gathered by analyzing and observing the sites directly through an observation checklist (field study/spatial analysis). This is presented in line with the second research objective.

Landscape Forms and Typologies

As stated earlier, the following areas were also considered in the spatial analysis: Dala (Dala and Kofar-mazugal) see (Table 1), Fagge (Fagge and Jabba) see (Table 2), Gwale (Gwale and Dorayi/Kabuga) see (Table 3), Kano Municipal (Sharada and Yakasai) see (Table 4), Kumbotso (Challawa and Kumbotso) see (Table 5), Nassarawa (Dakata Kawaji/Badawa and Hotoro) see (Table 6), Tarauni (Babbangiji and Unguwa Uku) see (Table 7) and Ungogo (Bachirawa and Ungogo) see (Table 8).

Table 1.

Observational checklist of the sampled environments in Dala local government area, Kano Metropolis.

Table 2.

Observational checklist of the sampled environment in the Fagge local government area, Kano Metropolis.

Table 3.

Observational checklist of the sampled environment in Gwale local government area, Kano Metropolis.

Table 4.

Observational checklist of the sampled environment in the Municipal local government area, Kano Metropolis.

Table 5.

Observational checklist of the sampled environment in the Kumbotso local government area, Kano Metropolis.

Table 6.

Observational checklist of the sampled environment in the Nassarawa local government are, Kano Metropolis.

Table 7.

Observational checklist of the sampled environment in the Tarauni local government area, Kano Metropolis.

Table 8.

Observational checklist of the sampled environment in the Ungogo local government area, Kano Metropolis.

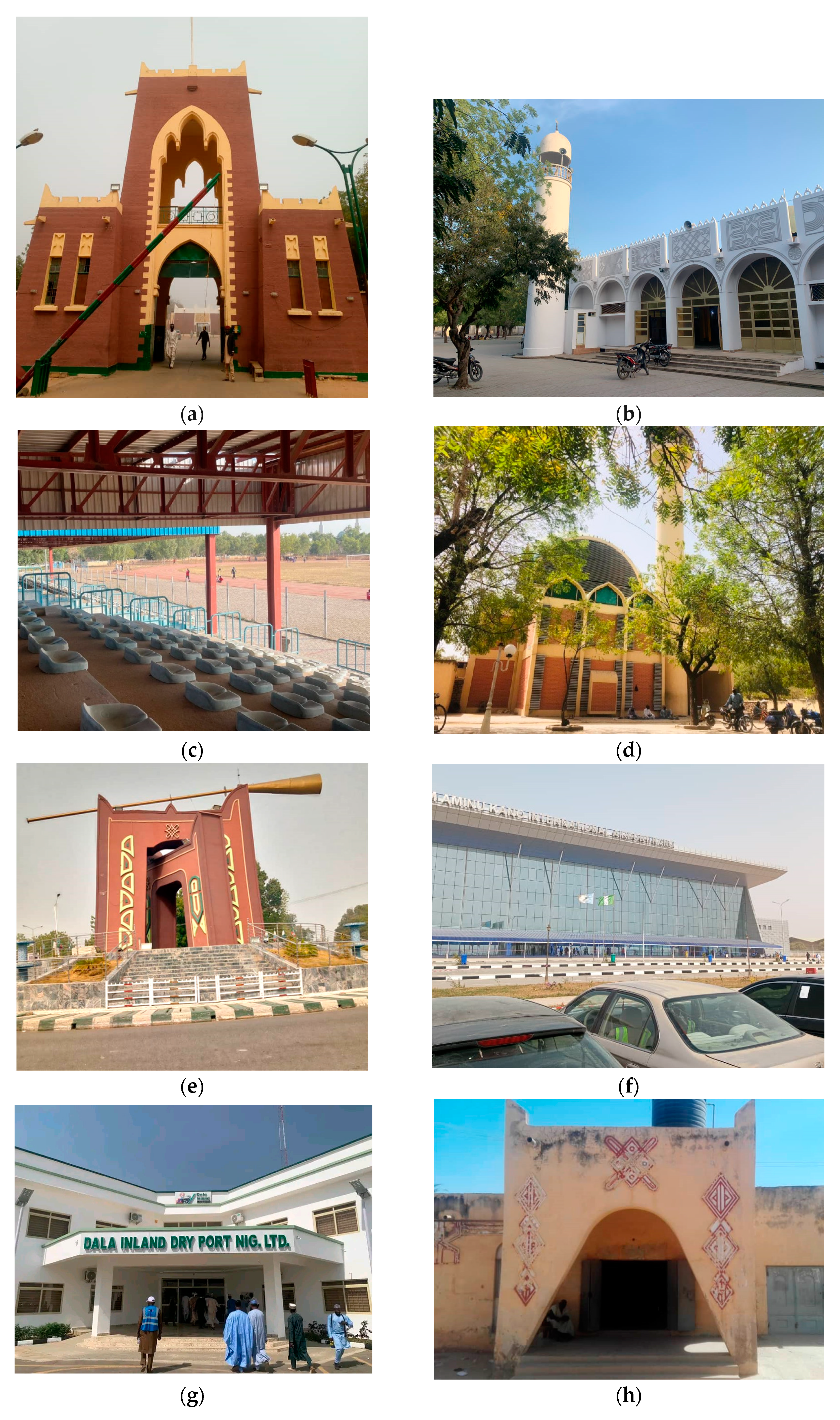

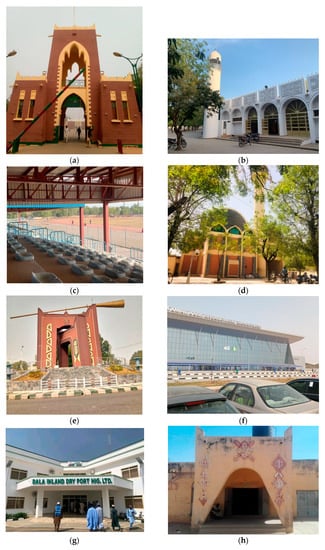

Physical observation carried out portrays the field study of landscape forms and its progression. Some of the Historic Urban Landscapes (HUL) within the sampled wards are presented as multiple sources of evidence in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Portrays the field study of landscape forms and its progression. As multiple sources of data from some of the Historic Urban Landscapes (HUL) within the sampled wards as presented in (a) Kofar kudu, Kano Municipal LGA; (b) Masjid IsyakuRabiu, G. Dutse, Dala LGA; (c) BUK Sport Arena, Old Site, Gwale LGA; (d) Masjid Murtala Muhammad, Tarauni LGA; (e) Golden Jubilee, State Rd, Nassarawa LGA; (f) MAK International Airport, Fagge LGA; (g) Dala Inland Dry Port, Kumbotso LGA; (h) District Head Residence, Ungogo LGA. Source: Authors, 2023.

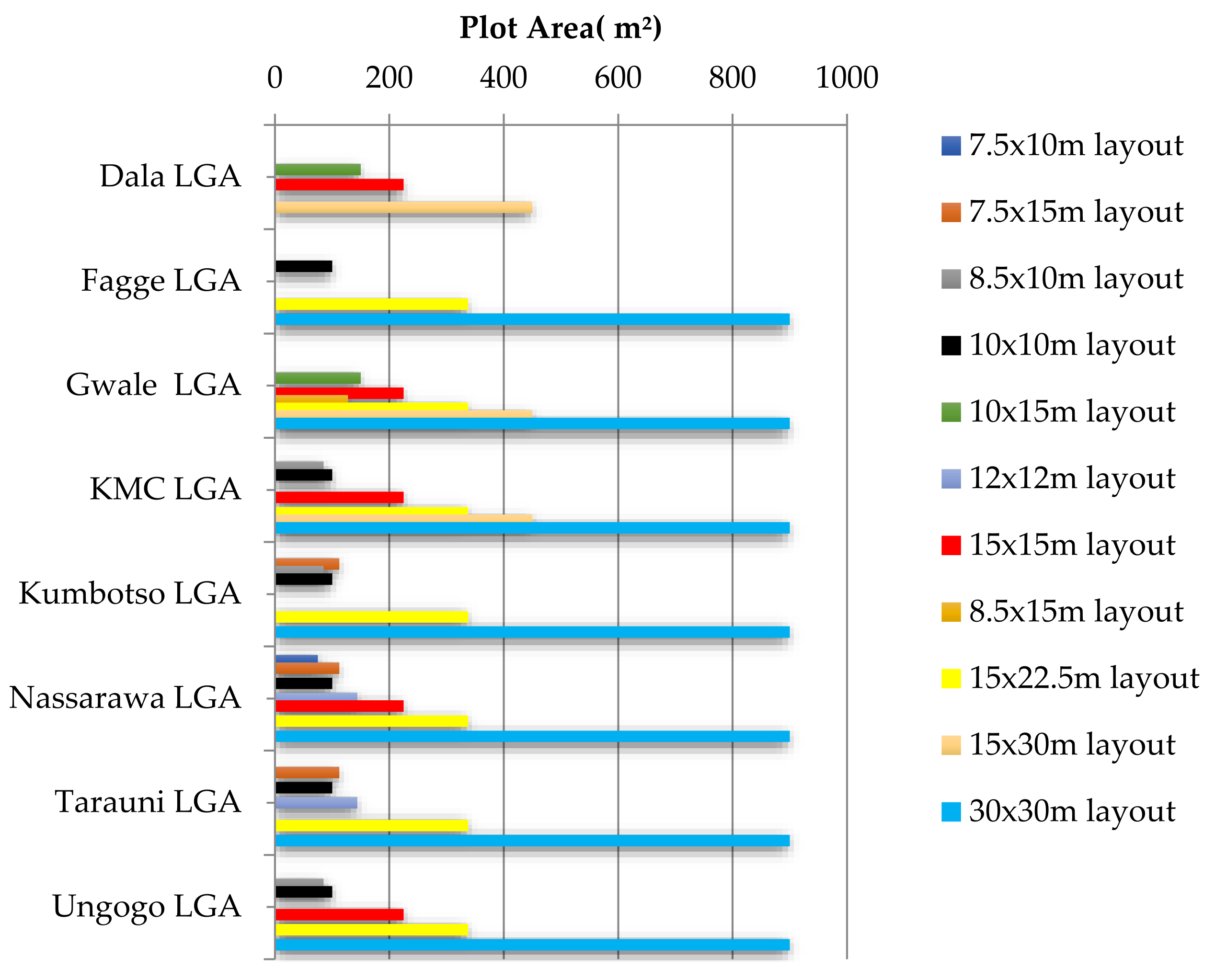

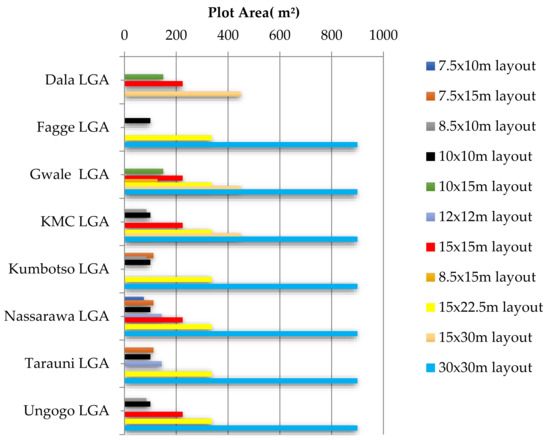

Furthermore, from the bar chart Figure 3 the study reveals the embodied layout distribution within the sampled wards. It unveils the predominant layout as 15 × 22.5 m distributed across the twelve sampled wards, including seven LGA. Then, 30 × 30 m is distributed across eleven wards, including six LGA. Finally, 10 × 10 mis distributed across ten (10) wards, including seven LGA. However, the stumpy layouts, 7.5 × 10 m and 8.5 × 15 m, were both found in one ward and LGA each. Then, 12 × 12 mis distributed across two wards and two LGA. The 15 × 22.5 m and 30 × 30 m have sufficient road networks in grid patterns, whereas stumpy layouts have poor accessibility routes.

Figure 3.

Kano Metropolitan embodied layout typology. Source: Authors, 2023.

- i.

- In the Dala local government area of Kano Metropolis, Dala ward has an organic and partly gridded arrangement with quite traditional Hausa–Fulani dwellings. However, Kofar-Mazugal ward has a squatter slum with partly traditional Hausa–Fulani dwellings.

- ii.

- The Fagge local government area, Kano Metropolis, comprises Fagge ward with a partly gridded layout and contemporary dwellings, and Jabba ward with a grid and partly irregular layout, as well as contemporary with a few traditional dwellings.

- iii.

- The sampled wards in the Gwale local government area are Gwale, which has an organic and partly gridded layout with traditional Hausa–Fulani dwellings, although transformed over time, while Dorayi/Kabuga has agridded and partly irregular layout with contemporary dwellings.

- iv.

- In Kano Municipal local government area, Kano Metropolis, Sharada ward has a gridded and partly organic layout with contemporary dwellings, whereas Yakasai ward has an organic and partly gridded layout with traditional Hausa–Fulani dwellings.

- v.

- The sampled wards in the Kumbotso local government area are Challawa, with a squatter slum and traditional Hausa–Fulani dwellings, and Kumbotso, which has a gridded and partly organic layout with contemporary and partly traditional Hausa–Fulani dwellings.

- vi.

- In the Nassarawa local government area of Kano Metropolis, wards such as Dakata/Kawaji/Badawa have a gridded and partly “Awon-Igiya” (Squatter slum) layout in the company of contemporary dwellings with partly ghetto settlements. On the other hand, Hotoro ward has a gridded and partly “Awon-Igiya” layout with contemporary and traditional Hausa–Fulani dwellings.

- vii.

- The sampled wards in the Tarauni local government area are Babbangiji/Darmawa/Hausawa which have an organic and partly gridded layout with contemporary dwellings. On the other hand, Unguwa Uku has a gridded and partly ghetto/contemporary outline with few traditional dwellings.

- viii.

- The Ungogo local government area constitutes Bachirawa ward, with an organic and partly gridded layout and contemporary dwellings, and Ungogo ward, which has a predominantly “Awon-Igiya” (ghetto) and partly gridded pattern and traditional dwellings with contemporary settlements.

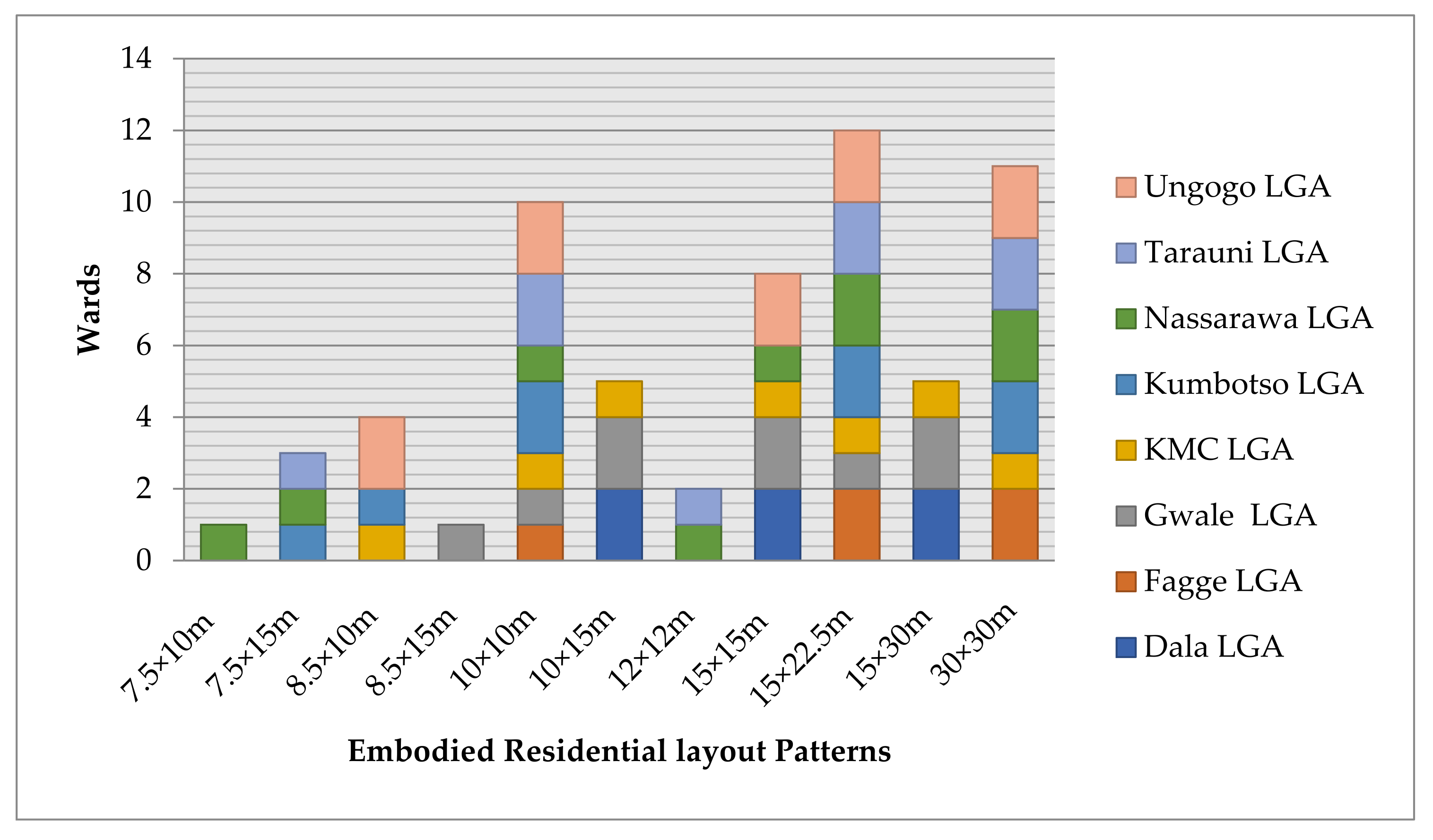

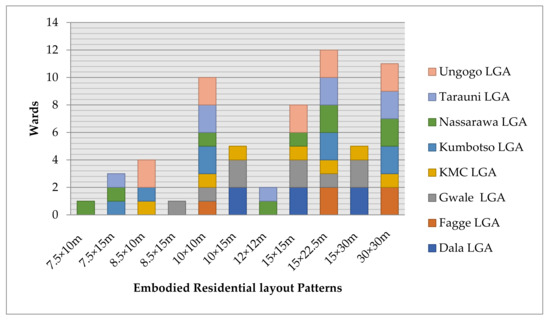

Additionally Figure 4 unveils the embodied residential layout pattern within the sampled wards. Where 15 × 22.5 m were the most predominant plot sizes observed in 12 wards followed by 30 × 30 m and then 10 × 10 m across the eight metropolitan local government. The 7.5 × 10 m is the least appeared residential plot size found in a single Ward within Nassarawa Local government. See Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Embodied residential layout pattern of plot sizes across eight metropolitant local governments. Source: Authors, 2023.

4. Discussion

According to [52], “there is a batch of infilling proceeding and external extension into bordering townships. Metropolitan Kano has been redefined vide Edict No. 15 of 1990. By the edict, Kano metropolitan area comprises of all territory within the radius of 32 kilometres from Kurmi market. Accordingly, the metropolis embraces Dala, Fagge, Gwale, Kumbotso Municipal, Nassarawa, Tarauni, and Ungogo Local government areas and fractions of Dawakin Tofa, Gezawa, Kura and Rimin Gado Local government areas”.

Developments in the21st century have incorporated adjoining hamlets such as Tokarawa, Fanisau, Ladanai, Medile, Yan-kunkuru, Yan-shana, Sabuwar Gandu, Baici and Limawa into the urban Kano and transformed it into a metropolis. Consequently, study shows that the landscape typology in the city of Kano can be dated back to the 15th century with the expansion of the city wall, and then, later, in the 16th and 17th century, respectively. In early 1900s, it was dominated by the British colonial administration, which comprises the space within the wall and the adjacent settlement just outside it. The reason for the transformation began with the inheritance by descendants of the deceased compound head, weather, and wealth. Subsequently, population congestion and relocation schemes, constructions and the establishment of industrial infrastructure played their role in the metropolitan transformation.

Furthermore, it further unveils that the model of planned landscape, when applied to an urban space, should not be confused with the ideas of townscape or cityscape which carry the specific connotation of buildings, streets, trees and gardens as elements of the city landscape. It should neither be confused with a city planner’s setting as revealed in maps and descriptions that are generally very specialized and professional views of what should or might come to be an urban landscape. Nevertheless, the city of Kano, “Binrin Kano”, is an undisputed case study of the evolution of a walled Hausa–Fulani city for the reason that so much of its urban landscape can be correlated with traditional typology, although further mapping and evaluation with frequent transformation is required. The urban landscape of Hausa cities in recent times has also gone through some alteration, from the cluster of cultural mythology to an Islamic and then a British colonist landscape configuration, as well as due to regional development policies.

More so, this study reveals that the physical forces of nature shape the landscape. As such, landscape is forced by these natural forces modified by human intercession. However, landscape is not under a human’s bearing or control and can be unpredictable as well. Yet, a third set of forces is attentive planning structures which the landscape in the land defines as the designed landscape. Table 9 alphabetically summarizes the Kano metropolitan urban landscapes within the sampled wards.

Table 9.

Summary of urban landscapes within the sampled wards.

From the foregoing, it is clear that the governance of cultural and ecological landscape is in very bad shape due to the dreadful conditions of Kano ecological landscape, which includes the backfilling of some water ponds (“Kudidifin Kukkuъa”, “Kudidifin Mai Allo”, “Kudidifin wafa”, “Kudidifin Pandaudu”, “Kudidifin Mammmaga”, and so forth), the under utilizing of Fanisau and Dorayi farm house and the vanishing of “Maitatsine” House to Yan Awaki market. In addition, the deterioration of Kano cultural landscape includes the degradation of the old city wall; the Dan Agudi to Kofar Fanfo link (Gwale), opposite S.A. Stadium (Yakasai), etc.; the gradual washing away of Dala Hill; and the re-building of city gates using concrete.

Although ref. [15] shows that landscape transformation in Kano city can be dated back to the 15th century, the expansion of the city wall was in the 16th and 17th century, respectively. Yet, it is worth noting that the historic urban forms in Kano seem to be degrading with time, or are rather not on the course of sustainability; this is because the physical environment is consistently modified to satisfy the immediate needs of the communities.

5. Conclusions/Way Forward

Based on the foregoing, this study could be said to have achieved its aim, as it has explored the historical establishment and landscape assets and layout typology of some residential environments within Kano metropolis. Even though it was carried out in some sampled wards, the research presents a valuable tool that would help the people of Kano and government agencies in the revitalization of its distorted urban landscape forms and planning typologies. However, in order to effectively utilize its findings to preserve and restore the Historic Urban Landscape, the following recommendations are offered:

- On implementing planning programs and development controls, it is recommended that unhealthy development should be discouraged and responsible government agencies should meet its expectations of controlling and regulating urban development, including the formal practice of land allocation, land acquisition, building codes, design, planning and construction.

- Landscape architects should be part and parcel of planning programs and development schemes.

- Integrating techniques for evaluating landscape values, problems and potentials should involve special protection and optimization measures for the urban landscape according to the current development.

- Increase in awareness at all levels (community, local and state levels) for protection, conservation and revitalization of historic landscapes and cultural heritage. This will aid the government and people in the state to redefine urban landscape forms.

- The government should also consider the implementation of the 2011 UNESCO proposals on the successful mapping of Historic Urban Landscape; it is a flexible activity that embeds policy, public involvement, economic empowerment conservation and building partnerships with relevant stakeholders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A.Y., J.Z. and A.Y.; methodology, D.A.Y. and J.Z.; software, S.A.N. and N.S.A.; validation, D.A.Y., J.Z. and A.A.; formal analysis, D.A.Y., A.M.U. and A.A.; investigation, A.S., A.S.H. and A.Y.; resources, A.A.; data curation, D.A.Y. and A.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, D.A.Y.; writing—review and editing, D.A.Y., J.Z. and A.A.; supervision, J.Z.; project administration, A.M.U.; funding acquisition, D.A.Y., S.A.N., A.M.U., A.S., A.Y., A.S.H., N.S.A. and A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

This is also to acknowledge the effort of Manir Ahmad Yakasai for providing language help during the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abass, K.; Buor, D.; Afriyie, K.; Dumedah, G.; Segbefi, A.Y.; Guodaar, L.; Garsonu, E.K.; Adu-Gyamfi, S.; Forkuor, D.; Ofosu, A.; et al. Urban sprawl and green space depletion: Implications for flood incidence in Kumasi, Ghana. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orire, A.M.; Huang, X.; Oloyede, O.I.; Ayo, B.; Raheem, W.A.; Chukwu, M. Papers in Applied Geography Spatio-Temporal Change Detection of Built-up Areas in Ilorin Metropolis and Implications for Green Space Conservation Spatio-Temporal Change Detection of Built-up Areas in Ilorin Metropolis and Implications for Green Space Cons. Pap. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 8, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelo, D.; Turpie, J. Land Use Policy Bayesian analysis of demand for urban green space: A contingent valuation of developing a new urban park. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, Y.M.; Diop, I.T.; Soulé, M.; Nafiou, M.M. Urban green spaces accessibility: The current state in Niamey city, niger. J. Glob. Ecol. Environ. 2022, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Woldesemayat, E.M.; Genovese, P.V. Functional Land Use Areas in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Their Relationship with Urban Form. Land 2021, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, D.A. Conceptualising Isolated Urban Corridors for Greenway Development Using Secondary Railway Neighbourhoods, Kano; Ahmadu Bello University: Zaria, Nigeria, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dyachia, S.; Sugandi, A.; Rafee, M.; Danladi, A.; Emmanuel, P. Urban Greenery a pathway to Environmental Sustainability in Sub Saharan Africa: A Case of Northern Nigeria Cities. Int. J. Built Environ. Sustain. 2017, 4, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasidi, N.A. Urbanism and the Conservation of The Natural Environment for Sustainable Development: A Case conservation of the natural environment for sustainable development. Lagos 2022, 87, 1–20. Available online: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03762087 (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Idris, H.A. Declining Urban Greenery in Kano Metropolis, Nigeria. J. L. Adm. Environ. Manag. 2022, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankani, I.M. Constraints to Sustainable Physical Planning in Metropolitan Kano. Int. J. Manag. Soc. Sci. Res. 2013, 2, 34–42. Available online: www.irjcjournals.org (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Adhikari, P.; de Beurs, K.M. Mapping and Analyzing Urban Growth: A Study to Identify Drivers of Urban Growth in West Africa; University of Oklahoma: Norman, OK, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Naibbi, A.I.; Umar, U.M. An appraisal of spatial distribution of solid waste disposal sites in Kano metropolis, Nigeria. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2017, 5, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.U.; Abdulhamid, A.; Badamasi, M.M.; Ahmed, M. Rainfall Dynamics and Climate Change in Kano, Nigeria. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2015, 7, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwadabe, S. Road Transport Problems in Kano Metropolis, Nigeria; Ahmadu Bello University: Zaria, Nigeria, 2012; Available online: https://kubanni-backend.abu.edu.ng/server/api/core/bitstreams/86771eea-dab3-4073-9975-b9f7fffff428/content (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- Liman, M.A. A Spatial Analysis of Industrial Growth and Decline in Kano Metropolis, Nigeria; Ahmadu Bello University: Zaria, Nigeria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehand, J. Urban Morphology and Historic Urban Landscapes. In Managing Historic Cities; UNESCO World Heritage Centre., University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Richthofen, F.V. Auƒgaben und Methoden der Heutigen Geographie; Inaugural Lecture: Berlin, Germany, 1883. [Google Scholar]

- Djoki, V. Morphology and Typology as a Unique Discourse of Research. SAJ Serb. Archit. J. 2009, 1, 107–130. [Google Scholar]

- Moughtin, C. Hausa Architecture; Ethnographica: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, G.U.; Yusuf, D.A. Socio—Cultural rejuvenation: A quest for architectural contribution in kano cultural. Int. J. Adv. Acad. Res. Soc. Manag. Sci. 2019, 5, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Tweed, C.; Sutherland, M. Built cultural heritage and sustainable urban development. J. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 84, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldpaus, L.; Roders, A.R.P.; Colenbrander, B.J.F. Urban Heritage: Putting the Past into the Future. In The Historic Environment; W. S. Maney & Son Ltd.: Leeds, UK, 2013; Volume 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, G.U.; Yusuf, D.A.; Mustapha, A. Evolution of Thematic Theory and Theorist the Regionalist Consortium. Int. J. Innov. Hum. Ecol. Nat. Stud. 2019, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, D.A.; Abdullahi, T.; Hamma, S. Urban Greenway Retrofit: Improving the Pedestrians Walking Experience of Kano Metropolis. Int. J. Adv. Res. Soc. Eng. Dev. Strg. 2016, 4, 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Jokilehto, J. International Charters on Urban Conservation: Some Thoughts on the Principles Expressed in Current International Doctrine, City & Time. City Time 2007, 3, 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, G.U.; Yusuf, D.A.; Mustapha, A. Theory and Design for the Contemporary Residential Buildings: A Case Study of Kano Metropolis. North-West. Part Niger. 2019, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape, Including a Glossary of Definitions (Paris: UNESCO). 2011. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/document/160163 (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Bandarin, F.; Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Girard, L.F. Toward a Smart Sustainable Development of Port Cities/Areas: The Role of the ‘Historic Urban Landscape’ Approach. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4329–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, H. Architecture for the Poor; an Experiment in Rural Egypt; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, G.U.; Yusuf, D.A.; Mustapha, A. Urban land use, planning and historical theories: An overview of Kano Metropolis. World Sci. News 2019, 118, 257–264. [Google Scholar]

- McDonell, G. The Dynamics of Geographic Change: The Case of Kano. Annals of the Association of American Geographers; Taylor & Francis: Singapore, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Barau, A.S.; Maconachie, R.; Ludin, A.N.M.; Abdulhamid, A. Urban morphology dynamics and environmental change in Kano, Nigeria. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntachiobi, A.I.; Godfry, E.N.; Agbaire, P.O. Distribution of Trace Elements in Surface Water and Sediments from Warri River in Warri, Delta State of Nigeria. World News Nat. Sci. 2017, 11, 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- MShediec-Rizkallah, C.; Bone, L.R. Planning for the sustainability of community-based health programs: Conceptual framework and future directions for research, practice, and policy. Health Educ. Res. 1998, 13, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsona, K.; Haysb, C.; Centerc, H.; Daleyd, C. Building capacity and sustainable prevention innovations: A sustainability planning model. Eval. Program Plann. 2004, 27, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Atiqul, H. Urban Green Spaces and an Integrative Approach to Sustainable Environment. J. Environ. Prot. 2011, 2, 601–608. [Google Scholar]

- Emechebe, L.C.; Eze, C.J. Integration of Sustainable Urban Green Space in Reducing Thermal Heat in Residential Area in Abuja. Environ. Technol. Sci. J. 2019, 10, 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Minjibir, N.A. Ancient Kano City Relics and Monuments: Restoration as Strategy for Kano City Development; Ahmadu Bello University: Zaria, Nigeria, 2012; Available online: http://kubanni.abu.edu.ng:8080/jspui/handle/123456789/2569 (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Olofin, E.A. Some Aspect of the Physical Geography of the Kano Region and Related Human Responses; Bayero University: Kano, Nigeria, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- NPC. Nigerian population Census report. 2006. Available online: www.npc.ng.org (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Kabir, G.U.; Yusuf, D.A.; Ahmed, A.; Usman, A.M. The practice of Hausa traditional architecture: Towards conservation and restoration of spatial morphology and techniques. Sci. Afr. 2019, 5, e00142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, H. Kano Chronicle in Sudanese Memoirs; Lagos Government: Ikeja, Nigeria, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Paden, J. Religion and Political Culture in Kano; California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, G.U. Transformation in Hausa Traditional Architecture: A Case Study of Some Selected Parts of Kano Metropolis (1950–2004); Ahmadu Bello University: Zaria, Nigeria, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart, A.W. Planned Urban Landscapes of Northern Nigeria: A Case Study of Zaria, 1st ed.; Ahmadu Bello University Press: Zaria, Nigeria, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Trevallion, W.C. Kano Metropolitan Twenty Years Development Plan 1963–1983; Greater Kano Urban Authority: Glasgow, Scotland, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Umar, M.A. Analysis of Spatial Morphology Using Space Syntex Method in Kano Metropolis; UCL: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fisherman, A. The Spatial Growth and Residential Location of Kano; North-Western University: Evanston, IL, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Ado-Kurawa, I. About Kano Research and Documentation Directorate; Government House: Kano, Nigeria, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Barau, A.S. Glimpses into Triple Heritage of the Kano Built Environment. In The Relevance of Traditional Architecture: Housing Rural Communities and Urban Poor; INTBAU: Kano, Nigeria, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dankani, I.M.; Ibrahim, M.S. The Implication of Fragmented Residential Land on the Built Environment of Metropolitan Kano, Nigeria; Bepress Publisher: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).