The Relationship between Urban Diversity and Residential Segregation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Urbanism-Metropolitanism

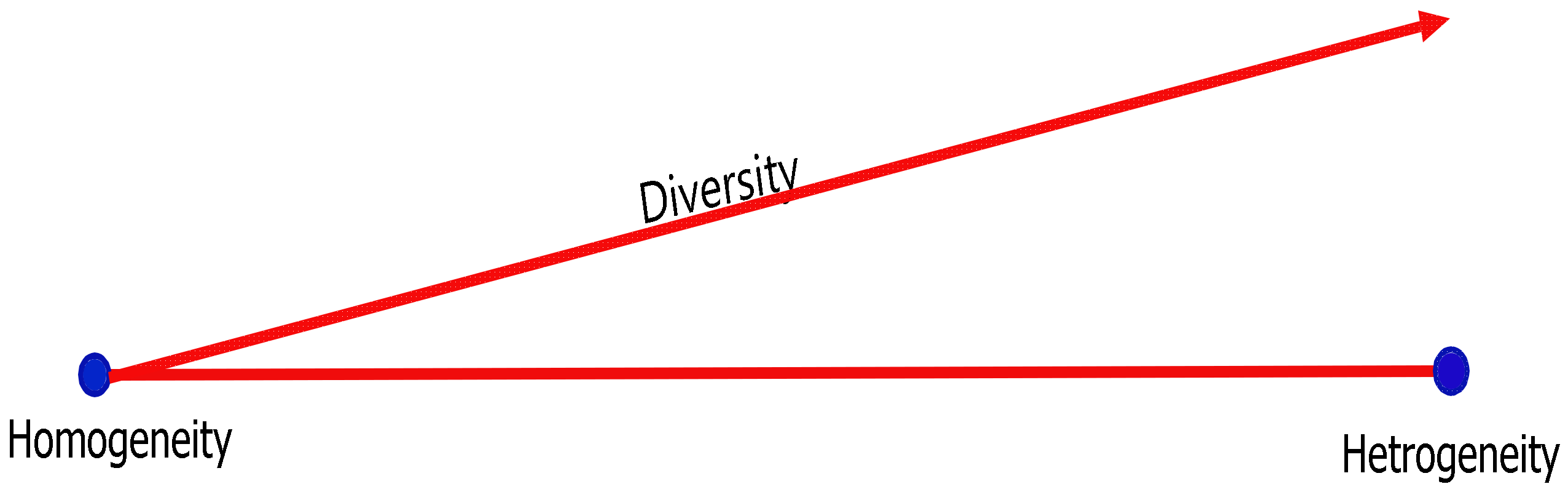

1.2. Differentiation—Diversity

- Homogeneity can be defined as the condition or state to which the members of a population belong to, and are in, the same category or background factor. It is the condition where diversity is zero.

- Heterogeneity can be defined as the condition or state in which members of a population belong to, or in, distinct categories of the same background factor, that is, the absence of homogeneity. It is the condition where diversity is non-zero, the more diversity, the greater the heterogeneity.

- Community Homogeneity can be defined as a condition, or state, in which the members of a population belong to and are in the same category within each background factor, that is, in a state of homogeneity for each identified dimension or background factor.

- Community heterogeneity can be defined as a condition or state in which the members of a population belong to and are in distinct categories within each background factor, that is, the absence of community homogeneity.

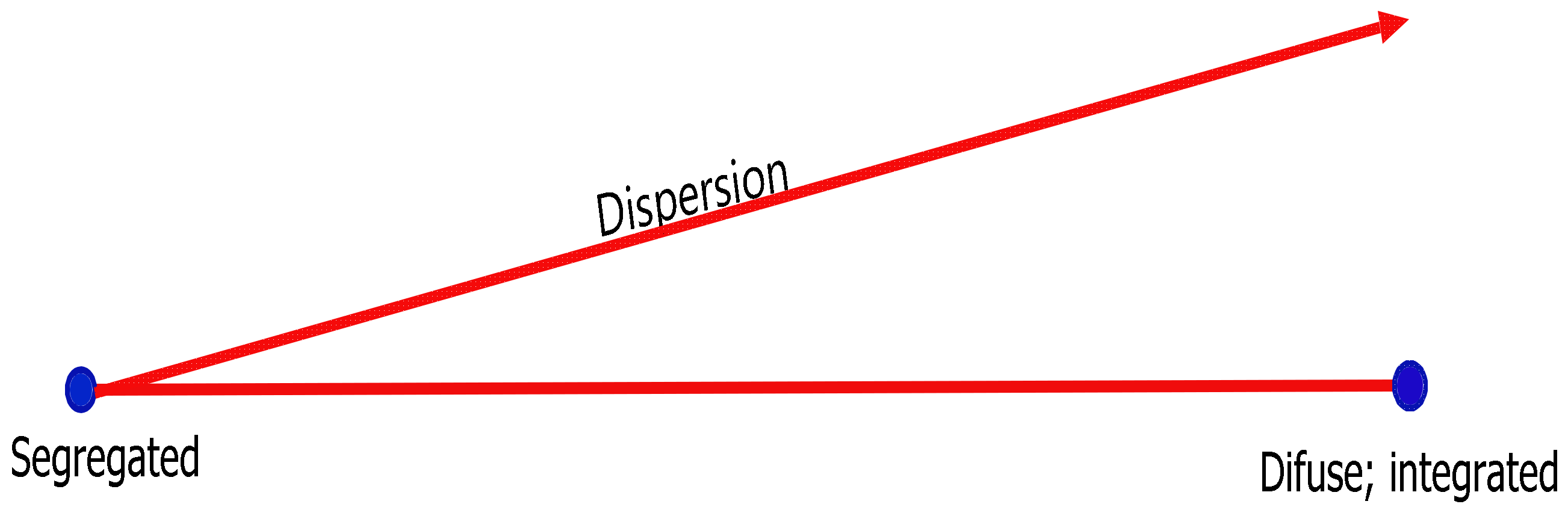

1.3. Differentiation—Residential Segregation

“The overall conclusion to be drawn is that active racial prejudice is a critical component of preferences for integration, and therefore, the persistence of racially segregated communities. Whites’ racial prejudice is a double whammy: influential not only for its effect on their own integration attitudes but also for its implications for minority group preferences and residential search behavior”.[17]

2. Data and Methods

2.1. The Characteristics

2.2. The Units of Analysis

2.3. Concept Operationalization & Measurement

2.3.1. Diversity

2.3.2. Residential Segregation

- Aspect. The first is the five elements of residential segregation presented first by Massey and Denton [45].

- Evenness. It is defined as the differential distribution of two social groups among the areal units. When the areal units have relatively the same number from each two groups, the greater the evenness—the more uneven the distribution, the greater the segregation.

- Exposure. This refers to the experience of segregation. If the minority and the majority groups share the same neighborhoods, the greater the exposure. There are two aspects, interaction, and isolation, which are measured slightly differently.

- Concentration. It is the physical space that is occupied by a minority in the city.

- Clustering. This is the extent to which a minority group occupies areal units adjacent to each other. High clustering means the presence of one or more ethnic or racial enclaves.

- Centralization. This is the degree to which a group is spatially located near the center of the urban area.

- 2.

- Scale. Three more broad issues with measuring segregation layered over these five dimensions of segregation affect the research direction. The first issue relates to a fundamental methodological conundrum: scale [41,48,49,50]. “Scale refers to the geographic level at which any phenomenon of interest is organized, experience, or observed…” [51]. The scale in which the analysis is conducted is crucial as it can produce different and sometimes contradictory results [52,53]. Most researchers would agree that in an ideal world, the research would be on an individual or household basis and not a spatially grouped basis. Grigoryeva and Ruef tackled this micro-scale by looking at the actual sequence of the census takers in the 1880 census for Washington D.C. [48]. The pattern of residential areas in the South was for non-whites to live on the same blocks as the whites but back behind them on the alleys. The use of blocks or other areal units shows a level of integration that really was/is not there. This partially accounts for the South showing less segregation than northern cities.

- 3.

- Pairwise or multigroup. The third concern is how the categories of the population are handled. Almost all dimensions for differentiating a population have more than one or two categories. Measuring diversity does not have this issue. There have been two fundamental approaches to measuring segregation. The first approach with segregation indices is that they typically only deal with two groups at a time and not all the groups, i.e., pairwise versus multigroup. For instance, segregation is measured between blacks and whites, Hispanics, and whites, etc. A multigroup index would consider all the groups (in this study, all eight groups).

- 4.

- Proximity. The fourth concern is how proximity and how space itself is managed, that is, how to account for the relationship between the areal units. In many ways, these are an attempt to overcome issues of the MAUP: aspatially, that is, the measurements are an overall view or a global view, disregarding spatial proximity, or the measurement deals with the issue of proximity (local view) [12,54].

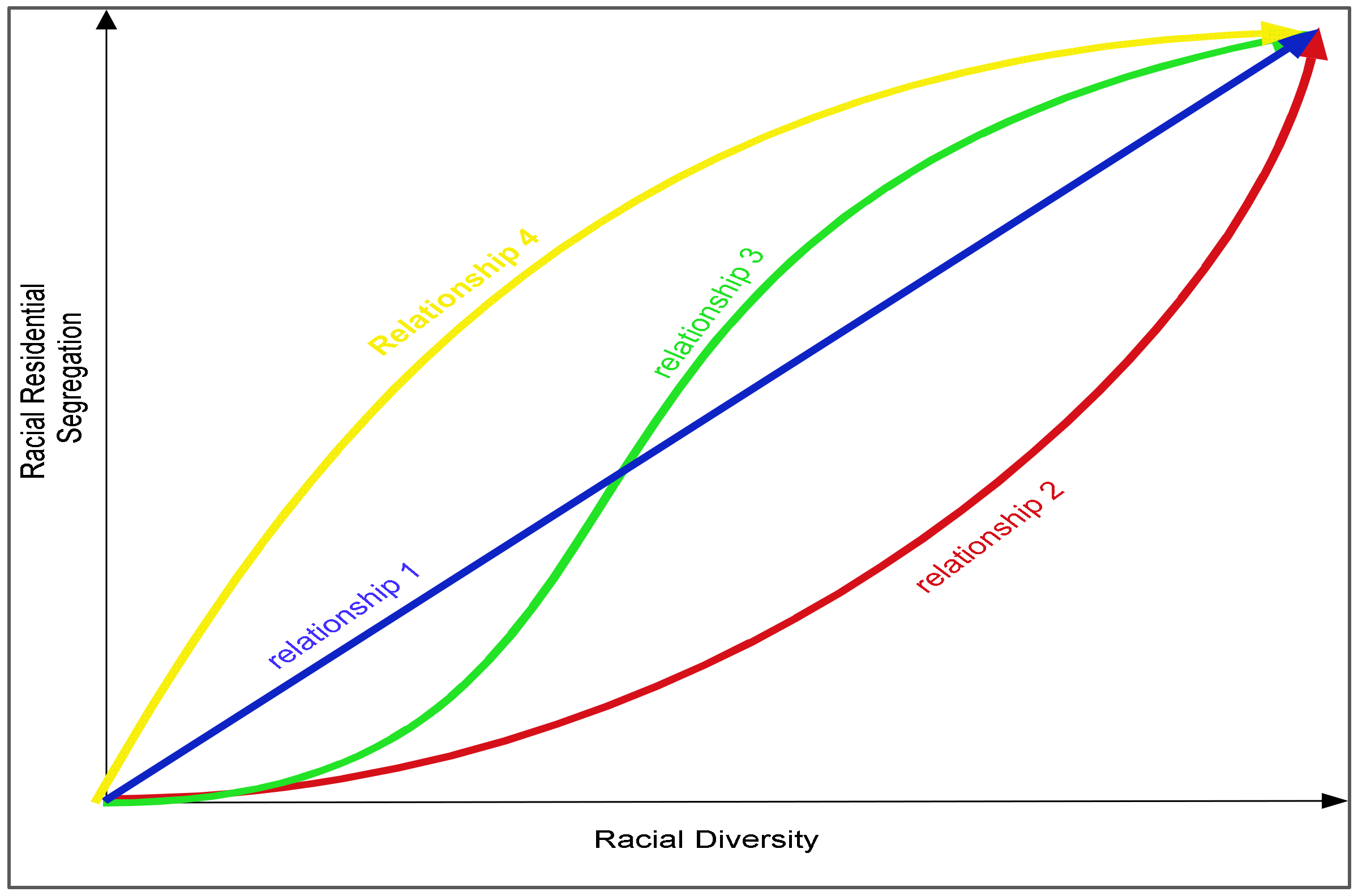

2.4. The Hypotheses

“We find that H has declined substantially in metropolitan areas, from 34 in 1980 to 23 in 2010 (Figure 13.5). That is, metro residents now live in census tracts that, on average, are 23 percent less diverse (or more segregated) than the metropolis as a whole, down from 34 percent less diverse three decades earlier.”

“The trend is clearly toward increasing diversity for whites and blacks in their neighborhoods because of the growing share of Hispanics and Asians in the overall population. The average white person now lives in a neighborhood with considerably larger shares of Hispanics and Asians, but only small increases of African Americans since 1980. African Americans now have more Hispanic and Asian neighbors, as well as a small increase in co-residence with whites.”[57]

“… whites rarely move into minority neighborhoods. Formerly all white neighborhoods are becoming more diverse as new groups move into them. There are many cases like this, but they are countered by growing segregation between other neighborhoods.”

“Hispanics and Asians have been moving toward new destinations since the 1980s, and this represents movement toward areas where they are less segregated. Yet in the process, their arrival has been met with increasing segregation.”

“Chicago deserves its reputation as a segregated city. But it is also an extremely diverse city. And the difference between those terms—which are often misused and misunderstood—says a lot about how millions of American city dwellers live. It is all too common to live in a city with a wide variety of ethnic and racial groups—including Chicago, New York, and Baltimore—and yet remain isolated from those groups in a racially homogenous neighborhood.”[58]

3. Results

3.1. Diversity

3.2. Segregation

3.2.1. Multigroup Dissimilarity Index (DG)

3.2.2. Pair-Wise Dissimilarity Index

3.2.3. Isolation Index

“Residential exposure refers to the degree of potential contact, or the possibility of interaction, between minority and majority group members within geographic areas of a city. Indices of exposure measure the extent to which minority and majority members physically confront one another by virtue of sharing a common residential area.”[39]

3.3. Relationship between Racial Diversity & Racial Segregation

4. Conclusions

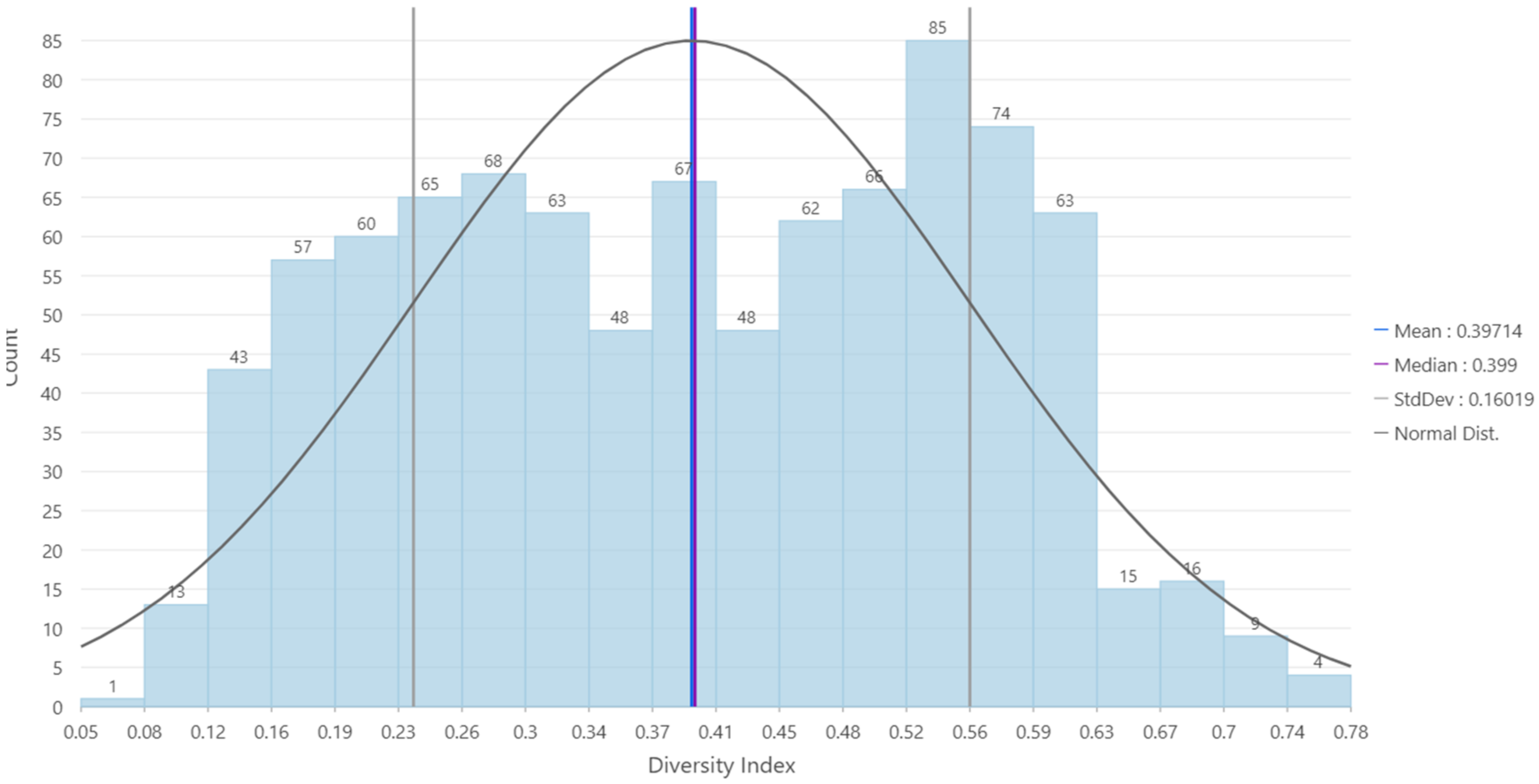

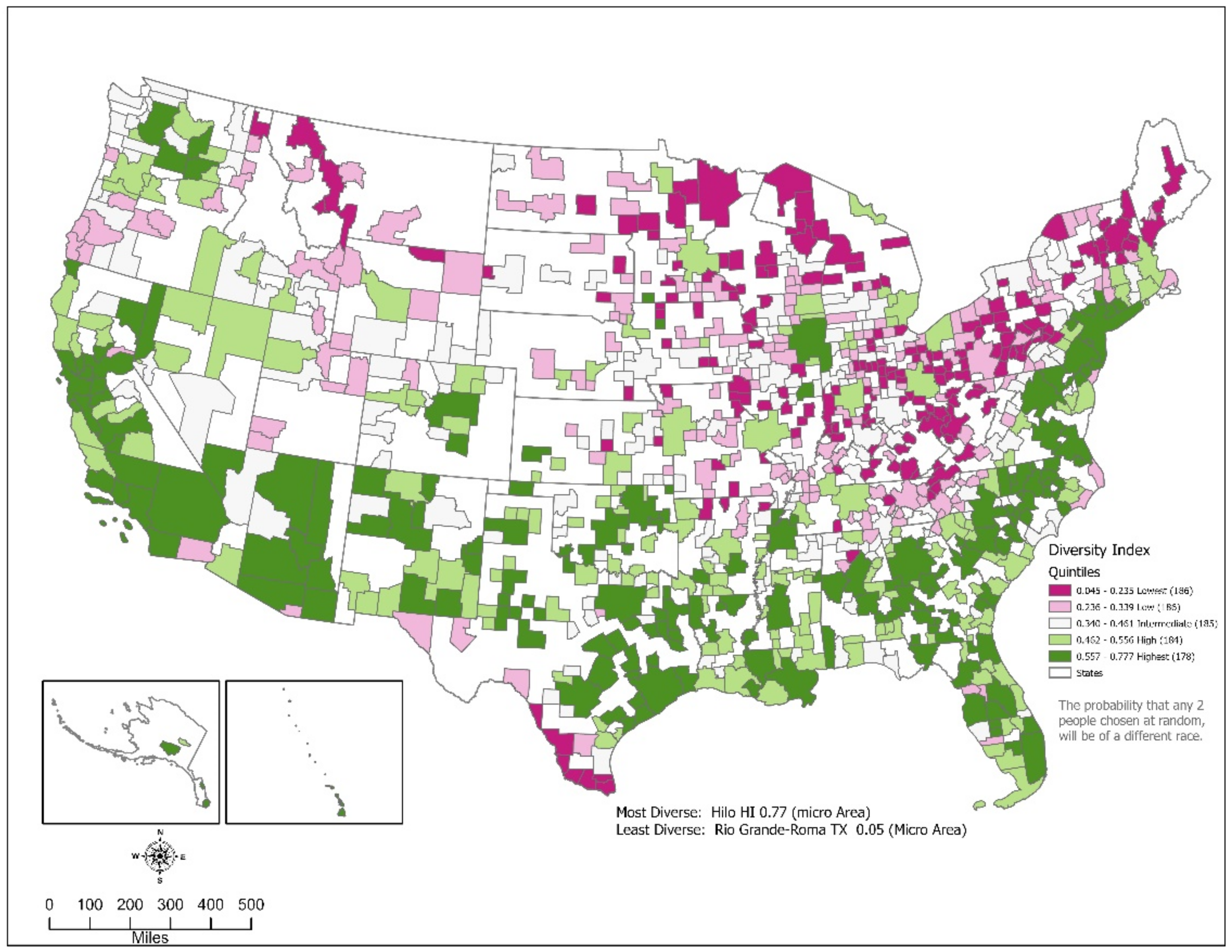

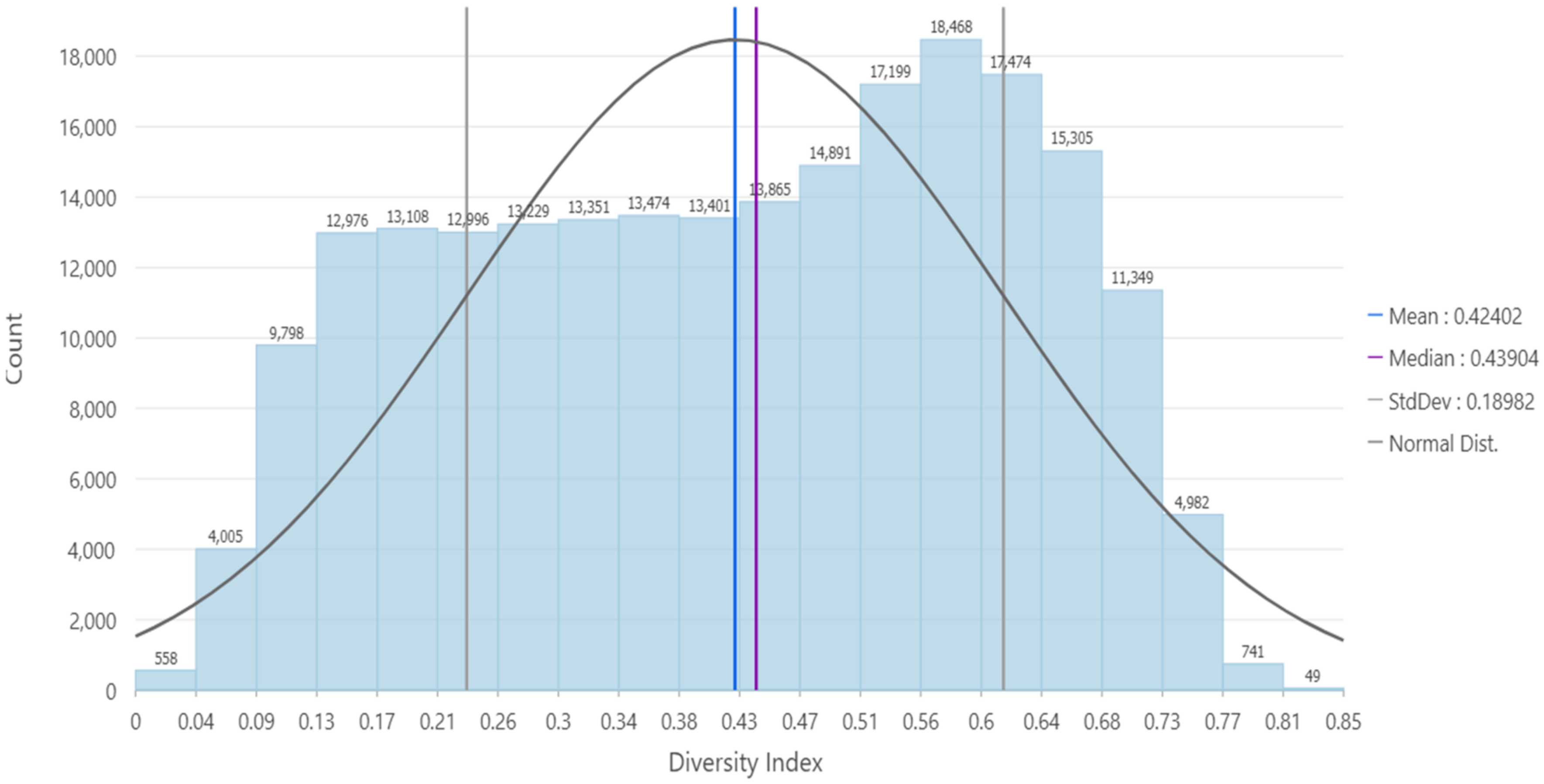

- The racial diversity indices had a bimodal distribution. The median index was 0.399 with an interquartile range of 0.276 and a broad range of 0.731. The South was the most diverse, while the northeast and Great Lakes region were the most homogenous.

- The Multigroup Dissimilarity Index had a median index of 0.318, an interquartile range of 0.131, and a broad range of 0.573. Multigroup dissimilarity was unevenly distributed geographically focused on the eastern half. Five areas had extreme values, over 2.5 standard deviations from the mean. The overall distribution of the races within the 927 metropolitan and micropolitan areas was uneven (i.e., “lumpy”).

- The differences in the pairwise racial dissimilarity indices clearly show the “lumpiness” of segregation.

- The Black-white dissimilarity index was the highest, thus displaying more residential segregation. The micropolitan areas were slightly less segregated than the metropolitan areas (medians were 0.437 and 0.499, respectively).

- Hispanic-white dissimilarity was relatively low, with a median of 0.312. The Hispanic dissimilarity ran from a low of 0.108 to a high of 0.663. The micropolitan areas (median = 0.292) were significantly less segregated than the metropolitan areas (median = 0.352). The highest indices were found in the country’s eastern half though California and New Mexico were also in the highest group.

- The Native American-white dissimilarity index was moderate, with a median of 0.380. Indices ran from a low of 0.091 to a high of 0.891. A relatively large number of areas (nine) fell in the extreme range. Geographically, the Native American indices were highest East of the Mississippi River and in the far Southwest. The indices were basically the same for metropolitan areas (median = 0.388) and the micropolitan areas (median = 0. 373). Oklahoma was an anomaly, with nine of the ten least segregated areas.

- Asian-white dissimilarity was high. The median was 0.399, with values ranging from a low of 0.136 to a high of 0.729. Segregation was highest in the Mid-Atlantic/Northeast, Midwest, and the South. California had several areas with high segregation. The Mountain region and the Pacific Northwest displayed the least segregation.

- The Isolation Index indicating the probability that a person chosen at random will interact with other group members in their block group had low indices in an absolute sense. There was a great deal of variation among each group and between the racial groups.

- The black isolation index had a median of 0.104, varying from a low of 0.002 to a high of 0.822. Areas with high indices were concentrated in the eastern half of the country. The metropolitan areas had higher indices than the micropolitan areas (medians of 0.192 and 0.063, respectively). All ten areas with the highest indices were in the South, and five were in Mississippi. The lowest indices were found in the western half of the country. There was a substantial overlap between Black-white residential segregation and black isolation. So, blacks were not only clumped together across the areas but were also isolated into the same block groups they would thus have more interaction and contact with other blacks.

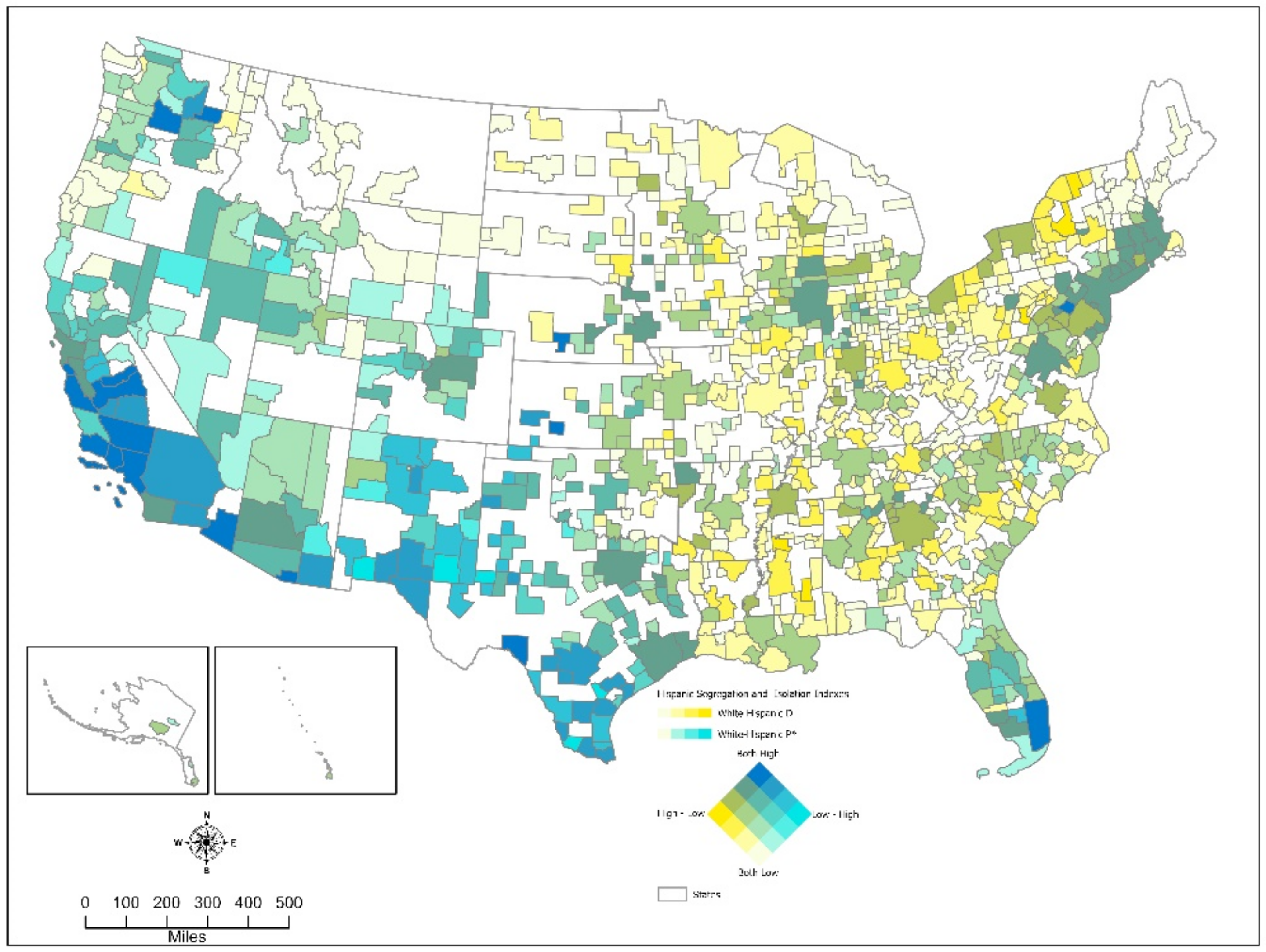

- The Hispanic isolation indices were slightly higher with a median of 0.114, ranging between 0.009 and 0.997. This was the largest range of values for any racial group. Metropolitan areas had higher indices (median = 0.150) than micropolitan areas (median = 0.084). The higher Hispanic isolation indices were geographically concentrated on the west coast and the Southwest, though Florida and the northeast coastal areas registered high values. Eight of the areas with the highest isolation indices were in Texas. All ten were found along the Mexican border. The west coast, particularly California, displayed the most areas with a substantial overlap of white-Hispanic dissimilarity and Hispanic isolation.

- Native American isolation indices were among the lowest. The median index was 0.006, ranging from a low of 0.001 to a high of 0.861. Metropolitan and micropolitan areas had basically the same median index, 0.006 and 0.005, respectively. Geographically, the highest Native American isolation indices were found in the West but were also clustered in the north-central states along the Canadian border, Oklahoma, North Carolina, and New York. These areas are the locations of reservations and traditional and historical tribal regions. Nine of the ten highest areas were in Arizona and New Mexico, with the other area being in New York. Oklahoma again was an anomaly, with relatively high Native American isolation indices while having relatively low dissimilarity indices. Several metro/micro areas in Arizona and New Mexico had significant overlap between Native American-white dissimilarity indices and the isolation indices. In these areas, Native Americans were not only clumped together, but they also had a high probability of only interacting with other Native Americans.

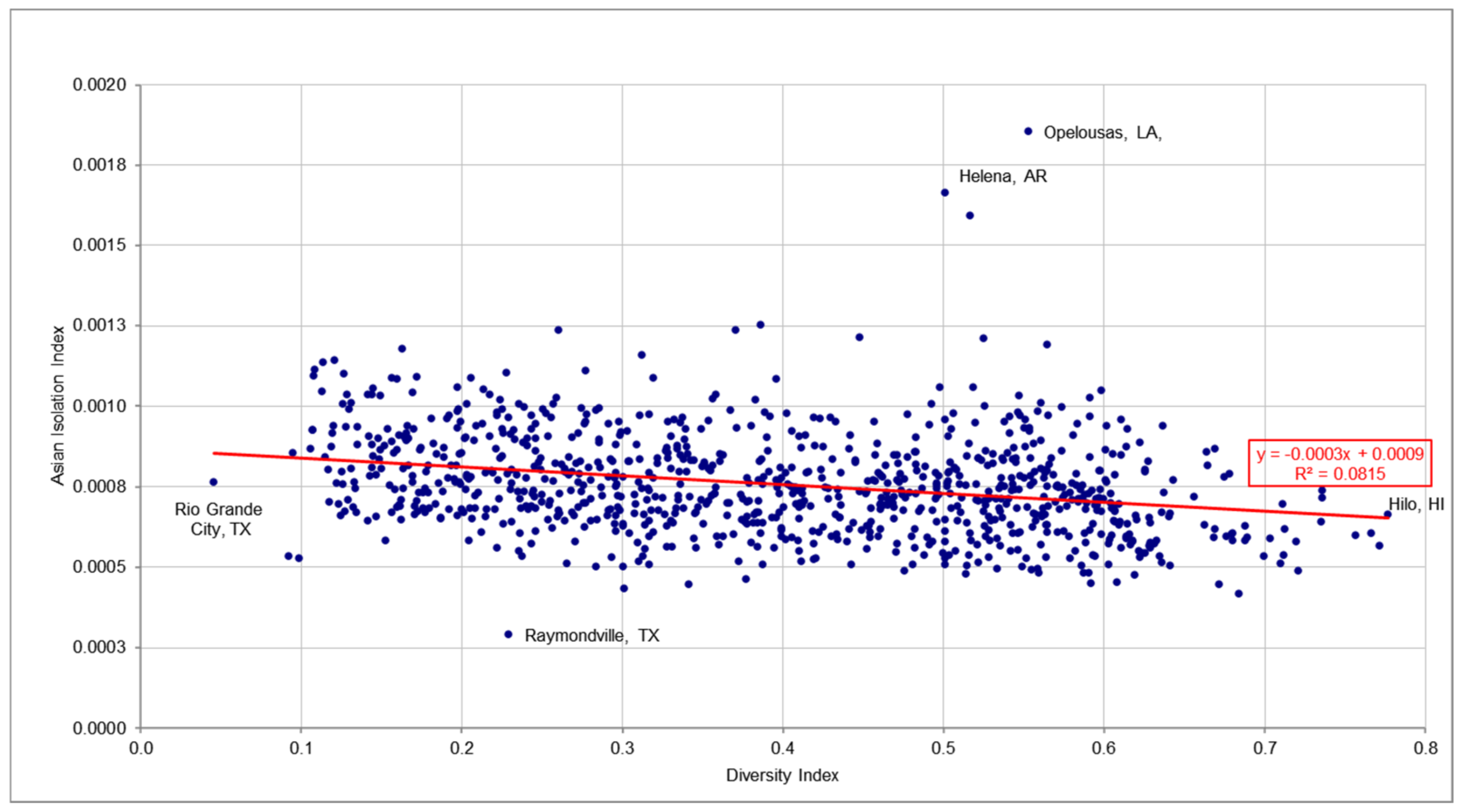

- Asian isolation was exceptionally low. The median was 0.001. Isolation was highest in the Great-lake region, the Rustbelt and the northern Midwest, and the pacific northwest. California had several areas with high isolation. The South and most of the Southwest had displayed the least Asian isolation.

- The racial diversity index was significantly related to the multigroup dissimilarity index as hypothesized (H1). The correlation coefficient was 0.422 with a slope of 0.249. As racial diversity increases within the metro/micro areas, so does the overall racial residential segregation amongst the eight racial groups.

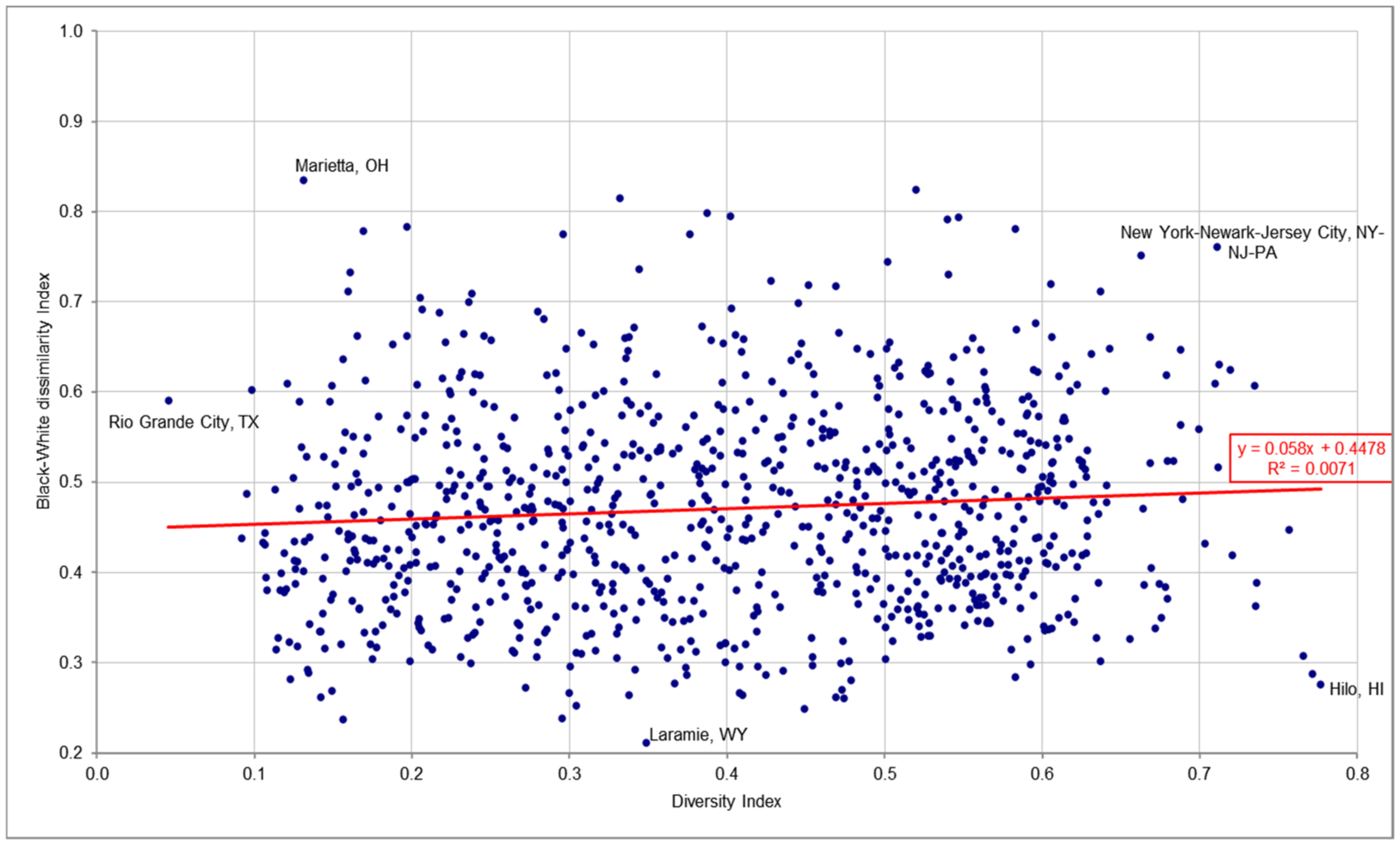

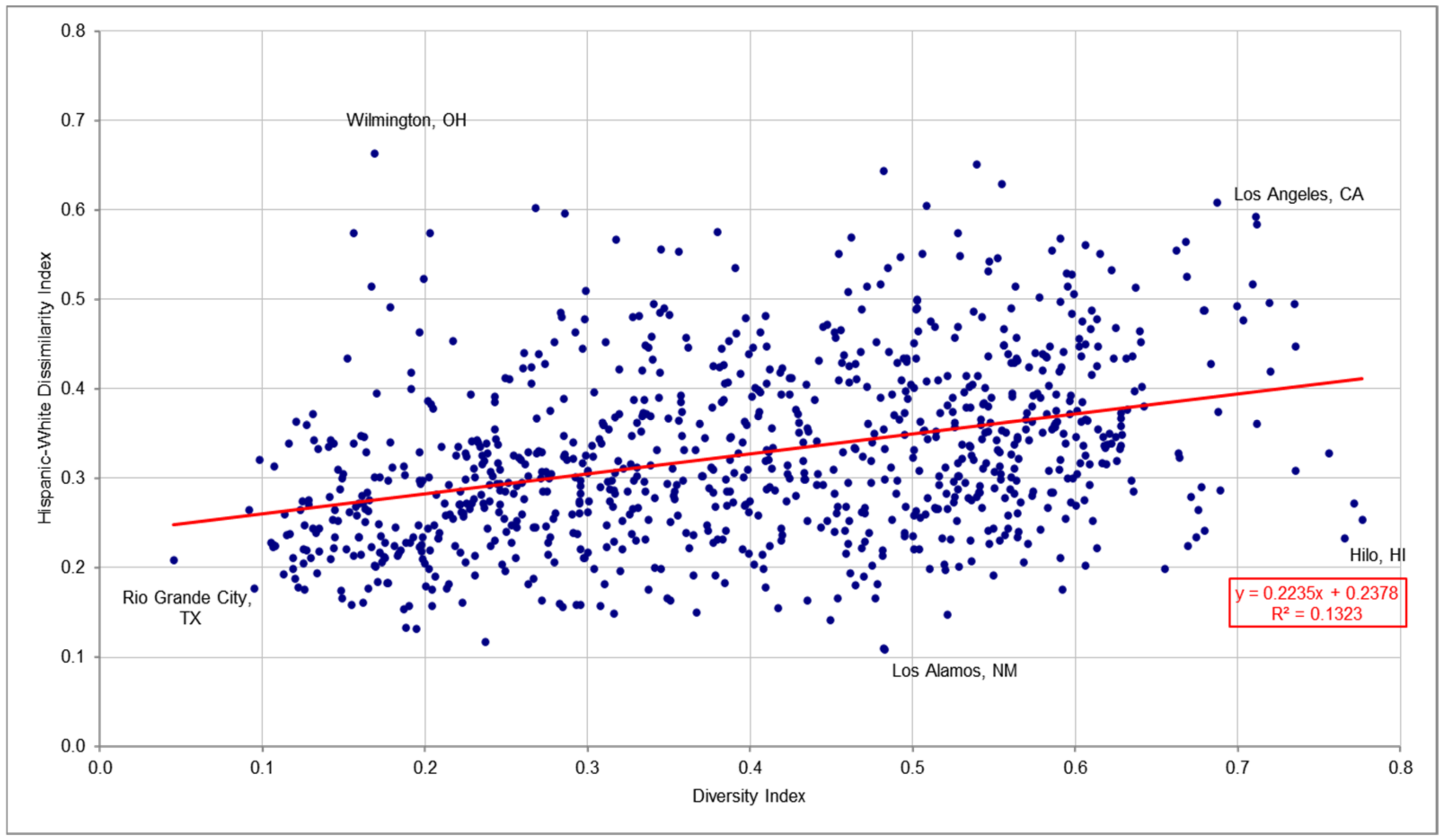

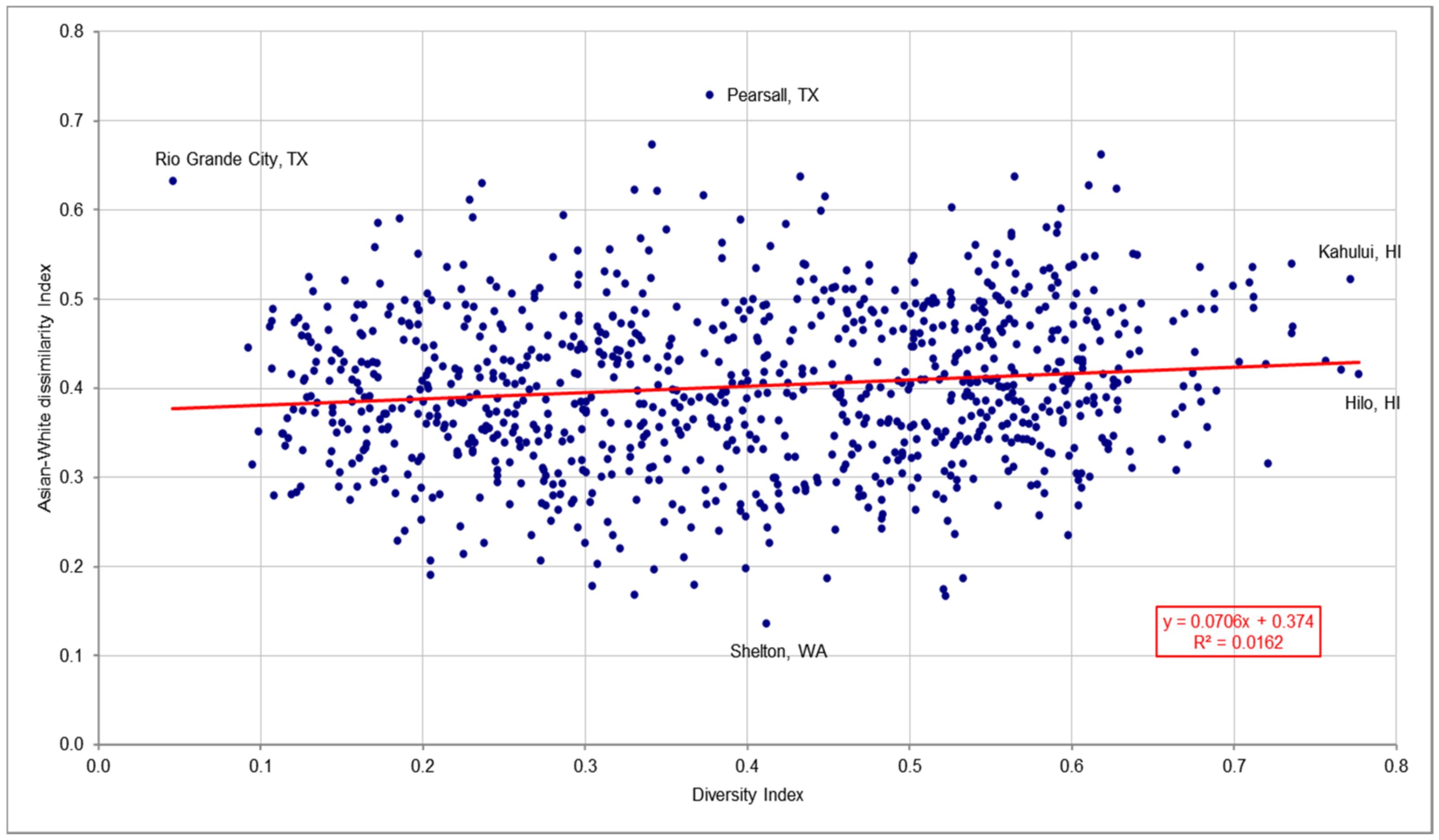

- The relationship between racial diversity and the pairwise dissimilarity indices varied by racial group.

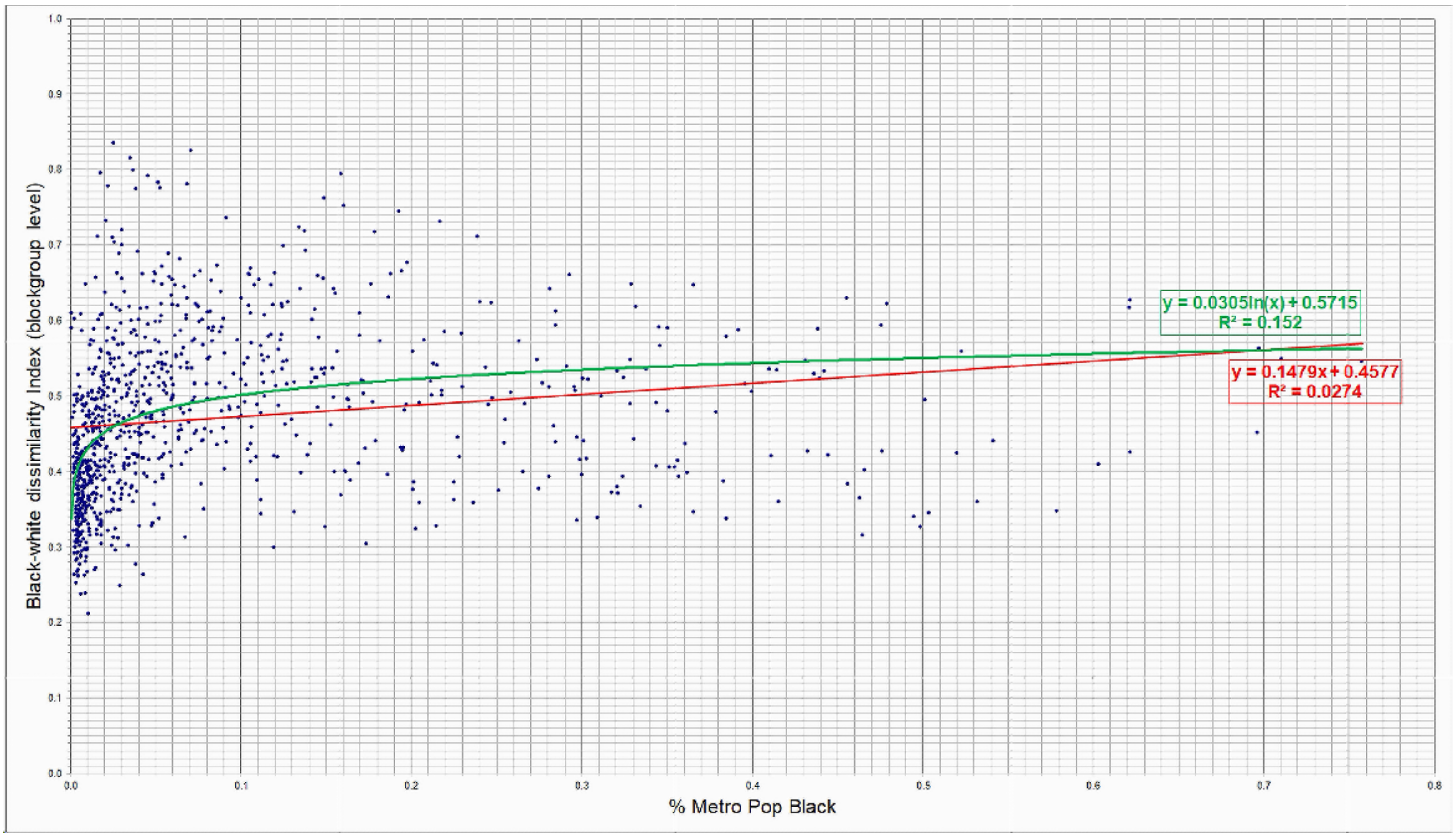

- The relationship between the Black-white dissimilarity index and racial diversity was linear but weak, with a correlation coefficient of 0.084 and a slope of 0.058. The hypothesis was not supported.

- Racial diversity and the Hispanic-white dissimilarity index were significantly related. The hypothesis (H2) of the relationship was strongly supported for this racial group. The correlation coefficient was 0.364, and the slope was 0.224. The connection was linear.

- Hypothesis (H2) is not supported other than very, very weakly. The Native American-white dissimilarity index was not significantly related to racial diversity. The correlation coefficient was −0.052, and the slope was −0.038. The relationship was inverse: the higher the racial diversity, the lower the racial residential segregation.

- Asian-white dissimilarity was significantly related to racial diversity. The correlation coefficient was 0.127 with a slope of 0.706. Hypothesis (H2) is supported for this racial group.

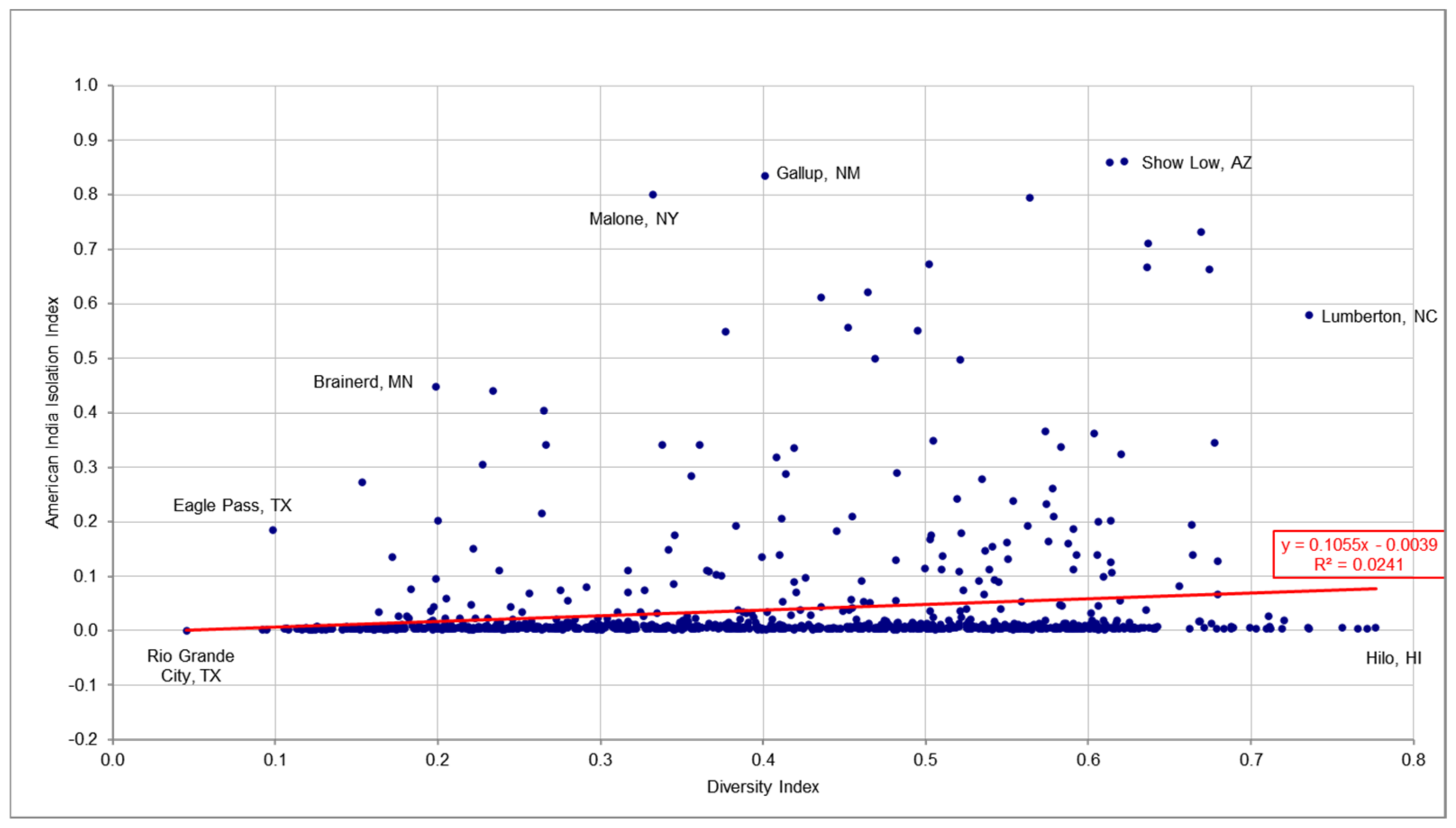

- The relationship between racial diversity and racial isolation also varied by racial group, though very strong positive correlations were found. Hypothesis H3 was supported.

- In contrast to diversity and the Black-white dissimilarity index, urban racial diversity and black isolation were significantly related. The relationship was linear, and the correlation coefficient was 0.482 with a slope of 0.554. Hypothesis H3 was confirmed for this group. The greater the racial diversity of the metro/micro areas, the greater the isolation of blacks.

- Racial diversity was also found to be significantly related to Hispanic isolation. The relationship was linear, with a correlation coefficient of 0.413 and a slope of 0.478. for Hispanics, hypothesis H3 was strongly supported. Here, too, the greater the urban racial diversity, the greater the isolation of Hispanics.

- For Native Americans, urban racial diversity was not significantly related to Native American isolation. What relationship existed was weak, so H3 was only weakly supported. It was linear, the correlation coefficient was 0.155, and the slope was 0.1055.

- For Asians, racial diversity was strongly related to Asian isolation (correlation coefficient of −0.285 and a slope of −0.00003). The relationship was the only inverse relationship between diversity and isolation—the greater the racial diversity, the lower the isolation of Asians.

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Esri Diversity Index: Growth in Diversity from 2000 to 2021. Available online: https://arcgis-content.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=a1803e6409a64f1cb4f0937bdd27a0ba#. (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- PolicyLink and USC Equity Research Institute (ERI). 2020 National Equity Atlas. Available online: www.nationalequityatlas.org (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- ARC Research. 2017 Diversity Index. 33n; ARC Research: Sliema, Malta, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- US News & World Report. How Racially and Ethnically Diverse Is Your City? Available online: https://www.usnews.com/news/cities/articles/2020-01-22/measuring-racial-and-ethnic-diversity-in-americas-cities (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Lichter, D.T.; Domenico, P.; Steven, M.G.; Michael, C.T. National estimates of racial segregation in rural and small-town America. Demography 2007, 44, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, D.S.; Nancy, A.D. Suburbanization and Segregation in U.S. Metropolitan Areas. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, 592–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, M. A Century of Delineating A Changing Landscape: The Census Bureau’s Urban and Rural Classification, 1910 to 2010. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Social Science History Association, Baltimore, MD, USA, 14 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, G.P.; Tallie, C. Diversity as a concept and its measurement. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1982, 77, 548–561. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, L. Urbanism as a Way of Life. Am. J. Sociol. 1938, 44, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sugihara, G. Diversity as a Concept and its Measurement: Comment. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1982, 77, 564–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. A Method for the Classification of Areas on the Basis of Demographically Homogeneous Populations. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1954, 19, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrill, R. On the Measure of Geographic Segregation. Geogr. Res. Forum 1991, 11, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D.S.; Jonathan, R.; Thurston, D. The Changing Bases of Segregation in the United States. ANNALS Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2009, 626, 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.J. The Measurement of Spatial Segregation. Am. J. Sociol. 1983, 88, 1008–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D.S.; Zoltan, L.H. The Changing Geographic Structure of Black-White Segregation in the United States. Soc. Sci. Q. 1995, 76, 527–542. [Google Scholar]

- Bruch, E.E. How Population Structure Shapes Neighborhood Segregation. Am. J. Sociol. 2014, 119, 1221–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, C.Z. The Dynamics of Racial Residential Segregation. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2003, 29, 167–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E.P. The Tipping-Point in Racially Changing Neighborhoods. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1963, 29, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.; LaDale, W.; Richard, M.; Connolly, N.D.B. Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America. 2022. Available online: https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=11/38.583/-90.319&text=intro. (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Thompson, C.W.; Cristina, K.; Natalie, M.; Roxana, P.; Corinne, R. Racial Covenants, a Relic of the Past, Are Still on the Books Across the Country. 2021. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2021/11/17/1049052531/racial-covenants-housing-discrimination (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Jenkins, D. The Bonds of Inequality: Debt and Making of the American City; Universty of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein, R. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Governent Segregated America, 1st ed.; Liveright Publishing Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson, I. The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Furst, R.; Jeff, H.; Mary, J. Webster Star Tribune. Racial Covenants Found Embedded in Ramsey County Property Deeds. 2022. Available online: https://www.startribune.com/the-racist-covenants-embedded-in-ramsey-county-deeds/600182442/ (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Méreiné-Berki, B.; György, M.; Remus, C. “You become one with the place”: Social mixing, social capital, and the lived experience of urban desegregation in the Roma community. Cities 2021, 117, 103302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysan, M.; Kyle, C. Cycles of Segregation: Social Processes and Residential Stratificatio; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. 2020 Census National Redistricting Data Summary File. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. tlgdb_2021_a_us_nationgeo.gdb. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/about/rdo/summary-files.html (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- US Census Bureau. DECENNIALPL2020.P2_2021-10-27T155053.zip. Available online: https://www.census.gov/geographies/mapping-files/time-series/geo/tiger-geodatabase-file.html (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Good, I.J. Diversity as a Concept and its Measurement: Comment. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1982, 77, 561–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberson, S. Measuring Population Diversity. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1969, 34, 850–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heip, C.; Peter, H.; Soetaert, K. Indices of diversity and evenness. Oceanis 1998, 24, 61–88. [Google Scholar]

- Keylock, C.J. Simpson Diversity and the Shannon-Wiener Index as Special Cases of a Generalized Entropy. Oikos 2005, 109, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Census Bureau. Racial and Ethnics Residential Segregation in the United States: 1980–2000. 2021. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2002/dec/censr-3.html (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Eric, J.; Jones, N.; Orozco, K.; Medina, L.; Perry, M.; Bolender, B.; Battle, K. Measuring Racial and Ethnic Diversity for the 2020 Census; US Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Fowler, C.S.; Barrett, A.L.; Stephen, A.M. The Contributions of Places to Metropolitan Ethnoracial Diversity and Segregation: Decomposing Change Across Space and Time. Demography 2016, 53, 1955–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Census Bureau. Racial and Ethnic Diversity in the U.S.: 2010 Census and 2020 Census; US Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Reese-Cassal, K. 2019 Esri Diversity Index. An ESRI White Paper; ESRI: Redlands, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, O.D.; Beverly, D. A Methodological Analysis of Segregation Indexes. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1955, 20, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitthiyot, T.; Kanyarat, H. A simple method for measuring inequality. Palgrave Commun. 2020, 6, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D.S. On the Measurement of Segregation as a Random Variable. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1978, 43, 587–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winship, C. A Revaluation of Indexes of Residential Segregation. Soc. Forces 1977, 55, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, B.S. An Alternate Approach to the Development of a Distance-Based Measure of Racial Segregation. Am. J. Sociol. 1983, 88, 1237–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakoda, J.M. A Generalized Index of Dissimilarity. Demography 1981, 18, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D.S.; Nancy, A.D. The Dimensions of Residential Segregation. Soc. Forces 1988, 67, 281–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, M.; David, W.S.W. Capturing the two dimensions of residential segregation at the neighborhood level for health research. Front. Public Health 2014, 2, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, S.F.; O’Sullivan, D. Measures of Spatial Segregation. Sociol. Methodol. 2004, 34, 121–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoryeva, A.; Martin, R. The Historical Demography of Racial Segregation. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 80, 814–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.A.; Sean, F.; Reardon, G.F.; Chad, R.; Farrell, S.A.M.; O’Sullivan, D. Beyond the Census Tract: Patterns and Determinants of Racial Segregation at Multiple Geographic Scales. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2008, 73, 766–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Measuring Residential Segregation. Available online: https://economics.yale.edu/sites/default/files/segregation-measures_03-24-14.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Jones, K.; Ron, J.; David, M.; Dewi, O.; Chris, C. Ethnic Residential Segregation: A Multilevel, Multigroup, Multiscale Approach Exemplified by London in 2011. Demography 2015, 52, 1995–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzzelli, M. Modifiable areal unit problem. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, M.; David, W.S.W. Spatializing Segregation Measures. Cityscape 2015, 17, 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, S.F.; Glenn, F. Measures of Multigroup Segregation. Sociol. Methodol. 2002, 32, 33–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, V. Lieberson’s Isolation Index; A Case Study Evaluation. Area 1980, 12, 307–312. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.; John, I.; Chad, B. Is ethnoracial residential integration on the rise? evidence from metropolitan and micropolitan america since 1980. In Diversity and Disparities: America Enters a New Century; Logan, J., Ed.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 415–456. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, J.R.; Brian, J.S. Metropolitan Segregation: No Breakthrough in Sight; US Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Silver, N. The Most Diverse Cities Are Often the Most Segregated. 2015. Available online: https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-most-diverse-cities-are-often-the-most-segregated/ (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Dinesen, P.T.; Kim, M.S. Ethnic Diversity and Social Trust: Evidence from the Micro-Context. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 80, 550–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metro/Micro Area | Total Population | Population Density | DI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hilo, HI Micro Area | 200,629 | 49.80 | 77.68% |

| Kahului-Wailuku-Lahaina, HI Metro Area | 164,754 | 141.84 | 77.14% |

| Kapaa, HI Micro Area | 73,298 | 118.245 | 76.59% |

| Vallejo, CA Metro Area | 453,491 | 551.807 | 75.64% |

| Urban Honolulu, HI Metro Area | 1,016,508 | 1692.42 | 73.58% |

| Lumberton, NC Micro Area | 116,530 | 123.013 | 73.55% |

| San Francisco-Oakland-Berkeley, CA Metro Area | 4,749,008 | 1922.40 | 73.51% |

| Las Vegas-Henderson-Paradise, NV Metro Area | 2,265,461 | 287.07 | 72.05% |

| Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV Metro Area | 6,385,162 | 972.206 | 71.94% |

| Trenton-Princeton, NJ Metro Area | 387,340 | 1725.51 | 71.20% |

| Metro/Micro Area | Total Population | Population Density | DI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rio Grande City-Roma, TX Micro Area | 65,920 | 53.89 | 4.55% |

| Laredo, TX Metro Area | 267,114 | 79.46 | 9.20% |

| St. Marys, PA Micro Area | 30,990 | 37.49 | 9.48% |

| Eagle Pass, TX Micro Area | 57,887 | 45.24 | 9.84% |

| Mount Gay-Shamrock, WV Micro Area | 32,567 | 71.78 | 10.54% |

| Coshocton, OH Micro Area | 36,612 | 64.92 | 10.68% |

| Jackson, OH Micro Area | 32,653 | 77.69 | 10.70% |

| Greenville, OH Micro Area | 51,881 | 86.74 | 10.72% |

| Spirit Lake, IA Micro Area | 17,703 | 46.52 | 10.81% |

| Warren, PA Micro Area | 38,587 | 43.64 | 11.30% |

| Metro/Micro Area | Total Population | Population density | DI | DG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Show Low, AZ Micro Area | 106,717 | 10.73 | 0.622 | 0.690 |

| Malone, NY Micro Area | 47,555 | 29.19 | 0.332 | 0.634 |

| Lexington, NE Micro Area | 26,004 | 17.68 | 0.540 | 0.588 |

| Greenwood, MS Micro Area | 38,337 | 31.36 | 0.506 | 0.564 |

| Nogales, AZ Micro Area | 47,669 | 38.56 | 0.286 | 0.561 |

| Cleveland-Elyria, OH Metro Area | 2,088,251 | 1044.76 | 0.502 | 0.559 |

| Milwaukee-Waukesha, WI Metro Area | 1,574,731 | 1082.39 | 0.547 | 0.558 |

| Cleveland, MS Micro Area | 30,985 | 35.35 | 0.510 | 0.558 |

| Detroit-Warren-Dearborn, MI Metro Area | 4,392,041 | 1128.40 | 0.540 | 0.551 |

| Monroe, LA Metro Area | 207,104 | 90.75 | 0.561 | 0.551 |

| Metro/Micro Area | Total Population | Population Density | DI | DG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sandpoint, ID Micro Area | 47,110 | 27.181 | 0.189 | 0.117 |

| Coeur d’Alene, ID Metro Area | 171,362 | 138.443 | 0.237 | 0.118 |

| Durant, OK Micro Area | 46,067 | 50.945 | 0.536 | 0.119 |

| Roseburg, OR Micro Area | 111,201 | 22.083 | 0.285 | 0.128 |

| Los Alamos, NM Micro Area | 19,419 | 177.955 | 0.483 | 0.128 |

| West Plains, MO Micro Area | 39,750 | 42.872 | 0.178 | 0.128 |

| Grants Pass, OR Metro Area | 88,090 | 53.758 | 0.308 | 0.128 |

| Tahlequah, OK Micro Area | 47,078 | 62.844 | 0.678 | 0.131 |

| Spearfish, SD Micro Area | 25,768 | 32.208 | 0.204 | 0.132 |

| Harrison, AR Micro Area | 44,598 | 31.612 | 0.176 | 0.132 |

| Black-White Dissimilarity Index | Hispanic-White Dissimilarity Index | Native American-White Dissimilarity Index | Asian-White Dissimilarity Index | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metro/Micro Area | Index | Metro/Micro Area | Index | Metro/Micro Area | Index | Metro/Micro Area | Index |

| Somerset, PA Micro | 0.835 | DuBois, PA Micro | 0.663 | Safford, AZ Micro | 0.891 | Pearsall, TX Micro | 0.729 |

| Sault Ste. Marie, MI Micro | 0.825 | Lexington, NE Micro | 0.651 | Malone, NY Micro | 0.872 | Utica-Rome, NY Metro | 0.674 |

| Malone, NY Micro | 0.815 | Reading, PA Metro | 0.644 | Show Low, AZ Micro | 0.862 | Napa, CA Metro | 0.662 |

| Cañon City, CO Micro | 0.799 | Salinas, CA Metro | 0.629 | Española, NM Micro | 0.833 | Lafayette-West Lafayette, IN Metro | 0.638 |

| Sonora, CA Micro | 0.795 | Los Angeles, CA Metro | 0.609 | Alamogordo, NM Micro | 0.831 | Cordele, GA Micro | 0.630 |

| Milwaukee, WI Metro | 0.794 | Springfield, MA Metro | 0.605 | Payson, AZ Micro | 0.828 | Rio Grande City-Roma, TX Micro | 0.633 |

| Lexington, NE Micro | 0.792 | Kendallville, IN Micro | 0.603 | Eagle Pass, TX Micro | 0.82 | Cortland, NY Micro | 0.630 |

| Huntingdon, PA Micro | 0.783 | Nogales, AZ Micro | 0.596 | Roanoke Rapids, NC Micro | 0.813 | Storm Lake, IA Micro | 0.628 |

| Susanville, CA Micro | 0.781 | New York City, Metro | 0.593 | Meridian, MS Micro | 0.802 | Bay City, TX Micro | 0.624 |

| DuBois, PA Micro | 0.778 | Trenton-Princeton, NJ Metro | 0.585 | Rio Grande City-Roma, TX Micro | 0.797 | Blacksburg-Christiansburg, VA Metro | 0.623 |

| Black-White Dissimilarity Index | Hispanic-White Dissimilarity Index | Native American-White Dissimilarity Index | Asian-White Dissimilarity Index | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metro/Micro Area | Index | Metro/Micro Area | Index | Metro/Micro Area | Index | Metro/Micro Area | Index |

| Laramie, WY Micro | 0.211 | Los Alamos, NM Micro | 0.108 | Durant, OK Micro | 0.091 | Shelton, WA Micro | 0.136 |

| Spencer, IA Micro | 0.237 | Fallon, NV Micro | 0.110 | Miami, OK Micro | 0.099 | Winnemucca, NV Micro | 0.167 |

| Casper, WY Metro | 0.238 | Coeur d’Alene, ID Metro | 0.117 | Muskogee, OK Micro | 0.114 | Truckee-Grass Valley, CA Micro | 0.168 |

| Pahrump, NV Micro | 0.249 | Kalispell, MT Micro | 0.132 | Ada, OK Micro | 0.118 | Hood River, OR Micro | 0.175 |

| Brookings, OR Micro | 0.253 | Sandpoint, ID Micro | 0.133 | McAlester, OK Micro | 0.127 | Brookings, OR Micro | 0.178 |

| Glenwood Springs, CO Micro | 0.26 | Pahrump, NV Micro | 0.141 | Tahlequah, OK Micro | 0.131 | Vineyard Haven, MA Micro | 0.179 |

| The Dalles, OR Micro | 0.262 | Winnemucca, NV Micro | 0.148 | Bartlesville, OK Micro | 0.147 | Pahrump, NV Micro | 0.187 |

| Pella, IA Micro | 0.262 | Price, UT Micro | 0.149 | Duncan, OK Micro | 0.151 | Carson City, NV Metro | 0.187 |

| Vernal, UT Micro | 0.264 | Vineyard Haven, MA Micro | 0.150 | Ardmore, OK Micro | 0.157 | Spearfish, SD Micro | 0.190 |

| Lawrence, KS Metro | 0.264 | Menomonie, WI Micro | 0.154 | Escanaba, MI Micro | 0.170 | Fremont, NE Micro | 0.197 |

| Black Isolation Index (P*) | Hispanic Isolation Index (P*) | Native American Isolation Index (P*) | Asian Isolation Index (P*) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metro/Micro Area | Index | Metro/Micro Area | Index | Metro/Micro Area | Index | Metro/Micro Area | Index |

| Clarksdale, MS Micro | 0.822 | Rio Grande City, TX Micro | 0.977 | Show Low, AZ Micro | 0.861 | Opelousas, LA Micro | 0.002 |

| Greenville, MS Micro | 0.804 | Laredo, TX Metro | 0.954 | Safford, AZ Micro | 0.86 | Helena, AR Micro | 0.002 |

| Cleveland, MS Micro | 0.788 | Eagle Pass, TX Micro | 0.952 | Gallup, NM Micro | 0.834 | Lafayette, LA Metro | 0.002 |

| Selma, AL Micro | 0.781 | Zapata, TX Micro | 0.939 | Malone, NY Micro | 0.801 | Las Vegas, NM Micro | 0.001 |

| Greenwood, MS Micro | 0.780 | McAllen, TX Metro | 0.929 | Payson, AZ Micro | 0.794 | Burlington, IA Micro | 0.001 |

| Indianola, MS Micro | 0.752 | Brownsville, TX Metro | 0.902 | Grants, NM Micro | 0.732 | Craig, CO Micro | 0.001 |

| Pine Bluff, AR Metro | 0.708 | Nogales, AZ Micro | 0.892 | Alamogordo, NM Micro | 0.711 | Indianola, MS Micro | 0.001 |

| Helena, AR Micro | 0.699 | Raymondville, TX Micro | 0.882 | Española, NM Micro | 0.673 | Pampa, TX Micro | 0.001 |

| Albany, GA Metro | 0.689 | El Centro, CA Metro | 0.873 | Flagstaff, AZ Metro | 0.668 | Lamesa, TX Micro | 0.001 |

| Orangeburg, SC Micro | 0.683 | Pecos, TX Micro | 0.855 | Farmington, NM Metro | 0.663 | Fort Madison, IA Micro | 0.001 |

| Black Isolation Index (P*) | Hispanic Isolation Index (P*) | Native American Isolation Index (P*) | Asian Isolation Index (P*) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metro/Micro Area | Index | Metro/Micro Area | Index | Metro/Micro Area | Index | Metro/Micro Area | Index |

| Zapata, TX Micro | 0.002 | Mount Gay, WV Micro | 0.009 | Rio Grande City, TX Micro | 0.001 | Raymondville, TX Micro | 0.0003 |

| Rio Grande City, TX Micro | 0.002 | Point Pleasant, WV Micro | 0.01 | Spirit Lake, IA Micro | 0.002 | Orlando, FL Metro | 0.0004 |

| Othello, WA Micro | 0.003 | Selma, AL Micro | 0.011 | Zapata, TX Micro | 0.002 | Boone, NC Micro | 0.0004 |

| Hailey, ID Micro | 0.003 | St. Marys, PA Micro | 0.012 | Carroll, IA Micro | 0.002 | Hinesville, GA Metro | 0.0004 |

| Burley, ID Micro | 0.004 | Jackson, OH Micro | 0.013 | Easton, MD Micro | 0.002 | Daphne-Fairhope-Foley, AL Metro | 0.0004 |

| Vernal, UT Micro | 0.004 | West Point, MS Micro | 0.013 | Johnstown, PA Metro | 0.002 | San Antonio, TX Metro | 0.0004 |

| Hood River, OR Micro | 0.004 | Warren, PA Micro | 0.013 | St. Marys, PA Micro | 0.002 | Raleigh-Cary, NC Metro | 0.0005 |

| Mountain Home, AR Micro | 0.004 | Brookhaven, MS Micro | 0.013 | Grenada, MS Micro | 0.002 | Pearsall, TX Micro | 0.0005 |

| Blackfoot, ID Micro | 0.004 | Elkins, WV Micro | 0.015 | Somerset, PA Micro | 0.002 | Lakeland, FL Metro | 0.0005 |

| Coeur d’Alene, ID Metro | 0.004 | Coshocton, OH Micro | 0.015 | Lebanon, PA Metro | 0.002 | Fayetteville, AR Metro | 0.0005 |

| HYPOTHESIS | Group | Correlation | Slope | Relationship | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Within Metropolitan and Micropolitan Areas and at the small grain level of block groups, the greater the degree of population differentiation on the characteristic of race as measured by the diversity Index (DI), the greater the level of residential segregation as measured by the Multigroup Index of Dissimilarity (Dg). | all 8 | r = 0.422 | 0.249 | linear | strongly supported |

| H2 | Within Metropolitan and Micropolitan Areas and at the small grain level of block groups, the greater the degree of population differentiation on the characteristic of race as measured by the diversity Index (DI), the greater the level of residential segregation as measured by the Index of Dissimilarity (D). | Black | r = 0.084 | 0.058 | linear | weak |

| Hispanic | r = 0.364 | 0.224 | linear | strongly supported | ||

| Indian | r = −0.052 | −0.038 | inverse | weak | ||

| Asian | r = 0.127 | 0.706 | linear | supported | ||

| Pacific | r = −0.221 | −0.280 | inverse | supported | ||

| Other | r = −0.116 | −0.059 | inverse | weak | ||

| Mixed | r = 0.213 | 0.071 | linear | supported | ||

| H3 | Within Metropolitan and Micropolitan Areas and at the small grain level of block groups, the greater the degree of population differentiation on the characteristic of race as measured by the diversity Index (DI), the greater the level of residential isolation as measured by the Isolation Index (P*). | Black | r = 0.482 | 0.554 | linear | strongly supported |

| Hispanic | r = 0.413 | 0.478 | linear | strongly supported | ||

| Indian | r = 0.155 | 0.106 | linear | weak | ||

| Asian | r = −0.285 | −0.0003 | inverse | supported | ||

| Pacific | r = 0.193 | 0.018 | linear | supported | ||

| Other | r = 0.149 | 0.007 | linear | weak | ||

| Mixed | r = 0.184 | 0.024 | linear | supported | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pendergrass, R.W. The Relationship between Urban Diversity and Residential Segregation. Urban Sci. 2022, 6, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci6040066

Pendergrass RW. The Relationship between Urban Diversity and Residential Segregation. Urban Science. 2022; 6(4):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci6040066

Chicago/Turabian StylePendergrass, Robert William. 2022. "The Relationship between Urban Diversity and Residential Segregation" Urban Science 6, no. 4: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci6040066

APA StylePendergrass, R. W. (2022). The Relationship between Urban Diversity and Residential Segregation. Urban Science, 6(4), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci6040066