Abstract

The present contribution to a neopragmatic approach to regional geography attempts to collect, structure, and reflect knowledge with different spatial, social, and cultural references. This is not a matter of designing a classical regional or landscape “compartmentalization” of distinct spatial units, which are characterized by a specific reciprocal shaping of culture and the initial physical substrate, but of investigating and reflecting the reciprocal influences of different levels of scale as well as the construction mechanisms and contingency of spatial units. By means of “theoretical” and also empirical “triangulation”, a differentiated picture of complex research objects—here Baton Rouge, LA—is generated, whereby (partial) contradictions between theoretical approaches and the relationship between the various appropriately chosen theories and equally well-chosen empirical methods are also accepted.

1. Introduction

In discussing the “materialistic turn” and the theoretical framing of multi-methodological studies, an approach has been developed in recent years within German-speaking human geography and in the sociology of space that has become called “neopragmatic” [1,2,3]. The focus is on the challenge of theoretically framing the various tangible aspects, individual and social/cultural dimensions, plus their interactions with each other, as they exist in complex phenomena such as landscape and spatiality [4]. This is a challenge that regional geography has to embrace since it is not limited to partial aspects, such as the social construction of spaces, but must be responded to in its synthesis [2,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. In philosophy, the neopragmatic approach is particularly associated with Richard Rorty [14,15] and also with Hilary Putnam [16]. With his postmodern approach of rejecting notions of universal truth as well as irrefutable objectivity and instead of acknowledging pluralistic worldviews as well as contingency, Rorty offers a framework for synthesizing different landscape and spatial aspects. Furthermore, neopragmatism is normatively oriented towards open-ended, democratic negotiation processes (see more precisely: [17,18,19]). The normative basis makes neopragmatism compatible with the political philosophy and sociology of the German-British philosopher Ralf Dahrendorf, who formulated the increase of individual “life chances” as a central social norm [20,21]: On the one hand, Ralf Dahrendorf’s reflections focus on the complex relationship of the individual to and in society, here in his role theory, in which he focuses on the constraints and possibilities of how the individual arranges himself in the “vexing fact of society”, develops it, but also influences it [22]. On the other hand, he deals with social, i.e., supra-individual conflicts, whose possibilities have a productive effect on the development of society [23,24]. In his resulting life chances approach, he follows Karl Popper [25,26] in his commitment to an open society that offers the individual as many life changes as possible, but whether these are used is the individual’s decision [20,27].

This study is part of a large number of studies that deal with the relationship between supra-local rationales and local specifics—being more economic oriented in the United States than in Western Europe—and their (urban) landscape results (among others [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]). This article is based on an extensive study of Baton Rouge [37] and focuses in particular on the multiperspective character of the neopragmatic approach and its suitability for regional geography.

The objectives of this article are divided into both theoretical/methodological and object-related:

- (1)

- The approach of “neopragmatic landscape research” is operationalized and examined for its viability;

- (2)

- The main developmental strands, incidents and supra-local influences on Baton Rouge are presented and interpreted;

- (3)

- The media representation of Baton Rouge focuses on the Internet—as a developing compartment of regional geography, in order to capture elements of its image and self-description;

- (4)

- Everyday life in Baton Rouge is examined in its meaning and attribution of meaning.

Baton Rouge is the capital of Louisiana, located on the lower Mississippi River (Figure 1). After New Orleans, Baton Rouge is the second-largest city in Louisiana. While the Baton Rouge metropolitan area joins the phalanx of US-scale medium-sized metropolitan areas characteristic of the South, Baton Rouge has several distinctive features that make it particularly suitable for geographic study, especially the testing of the synthesizing neopragmatic approach:

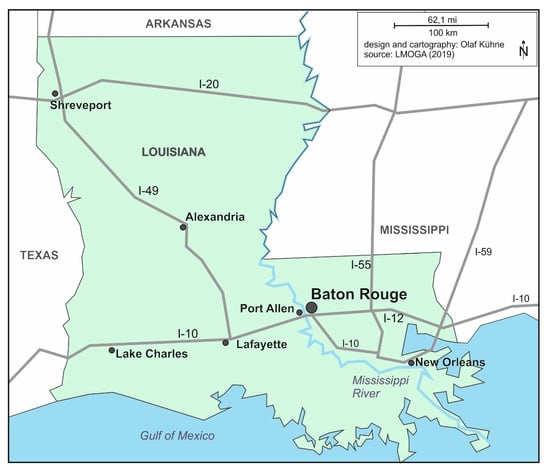

Figure 1.

The spatial location of Baton Rouge in Louisiana (own illustration).

- (1)

- A diverse economic, social, and territorial history, “having flown under ten flags” [38], “the flags of France, England, Spain, the independent republic of West Florida, the United States, and the Confederate States of America were flown over it, some of them more than once” [39]. This history continues in Baton Rouge today, in both the physical realm and in regional social self-description;

- (2)

- A “manageable” size, approximately 230,000 inhabitants with the metropolitan region over 500,000 inhabitants, allowing one’s investigations on the different dimensions to be carried out without the need for a research stay of several years;

- (3)

- Scant in regional geographic research (with one exception, discussed below), with only the historical aspects of the city has been intensively focused upon (some exceptions: [39,40,41,42]);

- (4)

- The only systematic regional geographic survey was carried out by a German geographer during the late 1950s and early 1960s. The results were published in German only, relatively unavailable to the American public [43]. These investigations, although implicitly following an essentialist-naive-realism paradigm that is hardly practicable currently, produced a great deal of empirical material useful for comparisons today, under a neopragmatic framework.

The “neopragmatic approach” pursued here goes far beyond a mixed-methods approach, as not only different methods are combined. “Triangulation” was originally understood as the division of an area into triangles for the purpose of measurement. Since the 1970s, “triangulation” has been used in empirical social research as a metaphor for combining qualitative and quantitative data collection or analysis methods. The aim here is to avoid one-sidedness that arises when only one type of data is used in a study, only one researcher collects and evaluates data, only one method is used. (as an overview sees among many [44,45,46,47]). In this article, a triangulation is carried out on four levels (see also Flick [48,49]):

- (1)

- Data triangulation. Data are combined from different sources, whether from official statistics, planning documents, scientific literature, but especially our own survey. In this last point, we go well beyond what regional geographies usually do [50,51]; here, the preoccupation is with data that were not collected specifically for this synthetic consideration.

- (2)

- Method triangulation. Here we use different methods of generating data and analyzing them. This ranges from methods of applied climatology to the quantitative and cartographic recording of land-uses and conducting and analyzing qualitative interviews to qualitative and quantitative media content analysis.

- (3)

- Researcher triangulation. This refers to joint research in a researcher tandem with different disciplinary backgrounds (geography/sociology and political science) as well as constant exchange with researchers and students in the field.

- (4)

- Theory triangulation. This is the essential aspect of the “neopragmatic” approach, as it additionally combines different basic theoretical positions where they offer high explanatory value for the complex spatial phenomena, such as a positivist perspective in the theoretical framing of the distribution of land-uses, a theoretical discourse one in relation to media representations of Baton Rouge.

In the following, the neopragmatic approach to regional geography, including the methodological orientation of the study, is presented, followed by a presentation of Baton Rouge spatial development. With social media importance increasing within social communication today, an investigation of this relative to Baton Rouge is performed. In conclusion, in addition to assessing the development of Baton Rouge against the background of Ralf Dahrendorf’s life chances approach, the question of the suitability of the neopragmatic approach for regional geographic research is evaluated.

2. The Neopragmatic Approach to Regional Geography

In order to illustrate the potentials of a neopragmatic approach for regional geographic research, we first briefly describe its history, on one hand, in the Anglo-Saxon (international) context, and on the other hand in the context of the age-old regional geographic research in Germany, in whose tradition we were socialized.

Although the detailed history of regional geographic research (let alone a comparison between the English-speaking areas and Germany) is presented here, some historical aspects of regional geography development seem essential to explain our striving for a new theoretical framework. Flourishing up until the 1960s, this form of geography, hitherto dominated by an essentialist paradigm supplemented by empirical methods, was gradually pushed out of the core of geographical research with the advent of the quantitative revolution coupled with a theoretical connection to human geography [50]. With the adoption of constructivist thinking (as in [52]), the awareness of regional knowledge interweaving with non-scientific patterns of interpretation and evaluation, plus the contingency of indicators and scientific perspectives, the “new regional geography” was born. This was initiated by Thrift and Gilbert (in addition in particular [8,53,54]) from various advanced theoretical perspectives, including Marxist and humanist approaches and theories of practice see [13,55,56]—also focusing attention on the interrelationships between the different levels of scale [9]. With the turn to the “new regional geography”, questions concerning discursive production of regions, beliefs in the existence of regions, identifying functions of regions, construction of borders, changing of institutionalizations and meanings, and similar questions arose (see [57]). What moved out of focus were substantive processes and regional bonds. With the emergence of these “more-than-representational” perspectives in human geography [58], regional geography can also be encouraged to strive for greater integration of the material dimension of space. This is the context in which the “neopragmatic approach” presented here arises. The triangulation of theories (and methods) inherent in the neopragmatic approach to regional geographies enables the integration of physical-geographical research results that have their origin in empirical methods (and, based on them, modeling) and are usually—mostly implicitly—framed in positivist theoretical terms.

As the name suggests, “neopragmatic approaches” integrate with pragmatic traditions, tracing back to American philosophers William James, Charles S. Peirce, and John Dewey, major influencers upon the Chicago School. Pragmatism orients towards the effects of the action that meanings and truths should determine action, not moral principles or grand theories. Usability thus becomes the touchstone of action, not consistency to principles [59,60,61,62]. Accordingly, “truth“, “theory“, “practice“, etc., are not thought separately but form “a unified entity mediated in the process of experience” [61]. Beyond the practical activity referencing pragmatic social and spatial research [61,63,64,65], the neopragmatism represented here exceeds its meta-perspective, although a goal orientation remains. Complex spatial entities, such as regions or landscapes, show both a material and a social-constructive dimension, also the dimension of individual consciousness (here we find connections to the three-world theory of [66]; relative to space: [67]). Correspondingly, the basic approach is based on Popper’s three-world theory: Karl Popper describes “world 1” as a world of living and non-living bodies, a material world. With “world 2,” he describes the individual level of the content of consciousness, of individual thoughts and feelings. “world 3”, on the other hand, comprises “all planned or intended products of human mental activity” [68]. The “realities” of these three worlds are not strictly separated but rather hybrid. So that a settlement is a part of “world 1” as well as of “world 3” and “world 2”. With this approach, Popper tried to create an alternative to worldviews that focus only on “world 1” as a materialistic world, or immaterialistic worldviews that recognize only “world 2”, as well as dualistic worldviews that recognize only “worlds 1 and 2” as “real” by adding “world 3”, “the world that anthropologists call ‘culture’” [68]. The abstract entities of “world 3” (including scientific theories, concepts, mathematical formulas, but also socially shared ideas about certain “things”) affect “world 2” through the process of socialization. The “world 2” in turn affects “world 1”, in that the human being, mediated by his body, materializes his ideas. These conceptions again he does not give birth from himself, but they originate in an argument with the contents of the “world 3” (see also Figure 2; for more on Karl Popper’s three worlds theory and its operationalization for spatial and landscape research, see, among others: [67,69,70,71]). Following this, we use in particular the superposition of the three worlds to three spaces by understanding “space 1” as material space, “space 2” the individual conceptions of space, “space 3” as the shared patterns of interpretation and evaluation of space. “space 1” and 2 are related by structuring the individual’s action (i.e., carrier of “space 2”) through matter, as well as the individual’s interpretation and evaluation of “space 1” through “space 2”. “space 3” affects “space 2” through socialization, whereby contents of “space 2” can also change “space 3”. According to the neopragmatic approach, we restrict ourselves to the use of the basic structure of the three worlds as well as the functional connections between the three worlds and exclude the detailed discussion (and criticism) of the ontological validity of the three worlds (for this, we refer to: [72,73,74,75]). Here the necessity of triangulation of theories becomes clear: theories represent abstractions of the world (or worlds) and are thereby focused in terms of content. If a complex topic, such as the synthetic consideration of space, is to be carried out from a regional geographic perspective, this requires the adoption of different perspectives and (justified) theoretical basic attitudes. At the same time, the neopragmatic approach also allows concentrating on parts of the theory that are useful for the investigation of one’s own question.

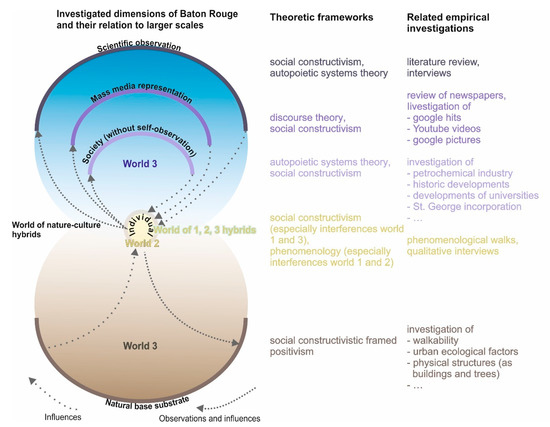

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the research design on neopragmatic approaches in terms of theoretical framing and methodological approach (own illustration [37]).

Relevant for a regional geographic synthesis is not only the principle existence of the three spaces and their connections but also the division into different scales, from local intrinsic logics to the effects of global developments in the examined space [28,76,77,78]. Such a complex subject cannot be treated mono-theoretically nor mono-methodologically (in a meaningful manner). Thus, it is an essential component to combine different methods and theoretical perspectives in ways adequate for the object. This also applies to (partially) contradictory perspectives, such as different constructivist ones: social constructivist, radical constructivist, discourse theory, also including combinations with empirical or positivist approaches [3,79]. Via “theoretical” and empirical “triangulation” methods, a differentiated understanding of a complex object can be achieved (for the concept of complexity, see [80]). Perspectives appropriate to different aspects of the complex “region”, thus, also enable integrative functions for physical and human-geographic observation [61]. Based within a selection of perspectives and methods, which is reflected and substantiated regarding the potential and limitation of knowledge. Their openness enables both interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary integration, thereby—in the sense of Rorty [14,15]—generating suggestions for dealing with space in terms of democratic or administrative action [1,81]. As an outcome of their theoretical and methodological openness, neopragmatic approaches also offer great potential for insights into issues requiring a certain amount of exploration. Thereby enabling the search for “useful” knowledge supporting the fundamental constructivist framework, whereby teleological thinking is contradicted [2].

This integration exceeds the classical approaches of a positively motivated collection of secured information and its graphic processing, additionally, the question of the production and powerful securing of regions, also opening up additional aspects, which arise within the increasing virtualization of the world. The exploration of Internet content, beyond a “proto-naïve positivism […] [in which] data […] are no longer collected, but ‘mined’ (data-mining)” [82] and unquestioned as facts. This also applies to non-visual stimuli [83,84] and the study of ambient aspects of environments by integrating phenomenological approaches [85,86], both having received little attention in regional geography.

A neopragmatic approach to “region” focuses particularly on dynamic processes because “stability is at best a temporary phenomenon” [61], which results from the high specificity of the different feedbacks occurring between structures and processes, thereby preventing “an exact predictability” [62]. Continuing the “new regional geography” legacy, the project deals with power relations in regards to the constitution and perpetuation of spatial units and processes of power distribution and safeguarding that take place within them (such as [55,87,88,89]). If spatial developments (regardless of whether we are moving on the level of “space 1”, 2 or 3) are not only to be described and analyzed but also interpreted and evaluated against the background of social functionality or dysfunctionality, it is scientifically honest to disclose the basis of these interpretations and evaluations [90,91,92]. This is followed by the issue of the analysis and evaluation of power, which, as mentioned initially, is based on Ralf Dahrendorf’s life chances approach. Contrasted with the rather Marxist mainstream of the discussion about city, or space and justice [93,94,95], Dahrendorf does not orientate himself to the Marxist tradition (which he criticizes, conversely). Placing himself in the tradition of Max Weber (from whom is borrowed the concept of “life chances”) and the model of an “open society” [25], Dahrendorf prefers the day-to-day struggle to find appropriate solutions to concrete challenges, both political and scientific.

Dahrendorf [96] perceives life chances as “choices, options”. These require “rights to participate and an offer of activities and goods to choose from”. Life chances are social context-dependent [20]. Life chances are possibilities of individual growth, the realization of abilities, wishes, and hopes, with these possibilities provided by social conditions. Life chances are not guarantees: “They only become concretely lived biographies through individual efforts—or they are forfeited” [97]. The life chances of people are determined by ligatures and options: “Options are choices given in social structures, alternatives of action” [20].

The individual needs “civilizational prerequisites, previous social knowledge and cooperative relationships” [97] in order to be able to develop individually (here, the feedback relationship of “world 2 and 3” in the Popper sense becomes very clear). Other people are therefore not simply “sparring partners” in the competition for their own success; they are “rather one of the most important sources of happiness and meaning in human life” ([98], also [20]). The meaning that life opportunities require is ultimately based on certain social “values that provide standards” [96]. Dahrendorf [96] calls these values, as “deep ties whose existence gives meaning to the opportunities for choice”, ligatures. These are strong affiliations that cannot be shaken off without anomie [99]; they are “structurally predetermined fields of human action. The individual is placed in bonds or ligatures by virtue of his social positions and roles” [20]). Ligatures prove to be emotionally charged: “the ancestors, the home, the community, the church” [20]. Ligatures create references and are considered “foundations of action” [20]. Options demand “electoral decisions and are thus open […] [for] the future” [20]. Ligatures and options are subject to a mutual influence: “Ligatures without options mean suppression, while options without bonds are meaningless” [20]. Although ligatures turn mere opportunities into “opportunities with meaning and significance, i.e., life chances”, they are not the same thing [100], but they are always associated with the danger of social sclerotization. For Dahrendorf, the development of life chances is the central political task because their maximization means the exhaustion of the “potential of a society” [20]. These life chances are individual, to be sought and won individually, he rejects—like Karl Popper, whom he follows, and also Richard Rorty—the idea that history has a priori or “even a posteriori meaning” ([20]; an in-depth examination of Dahrendorf’s life chances concept contextualization in his political philosophy and sociological theory in [101]).

The methodology of a study of metropolitan Baton Rouge derived from this theoretical framework is presented below.

3. The Methodological Operationalization of the Neopragmatic Approach to the Study of Baton Rouge

In accordance with neopragmatic regional geography approaches as developed above, we have assigned different theoretical perspectives and methodological approaches to the dimensions of the material substrate, individual access, and social construction, plus their interrelations. The central objective here was to generate a synthetic overview rather than to conduct focused sub-studies. Accordingly, the investigation of the individual subareas was carried out with fewer cases or keywords overall, also in order to establish comparability with other study areas in the USA, such as San Diego or Los Angeles. Here, we only present the assignment of theories and methods; more detailed information on methodology is in the presentation of the results (see in more detail [37]).

The underlying aspects were grounded in the positivist perspective, methodologically operationalized primarily by measuring and counting, but also by processing literature and cartographic material applying the positivist paradigm. For example, land-use was mapped, air temperature, and humidity or acoustical pressure measured and cartographically processed. The assessment of Baton Rouge social construction, framed by social constructivism and discourse theory, was methodically supported by media content analyses (newspapers, Google hits, Internet videos, Internet images, music with the theme Baton Rouge; [102,103,104]). The New York Times, one of the most widely circulated newspapers in the US [105], was chosen to capture a national media perspective on Baton Rouge. A total of 138 articles on the keyword “Baton Rouge” (adjusted for family ads) in three selected volumes (1979, 1999, 2019) were first assigned and quantitatively evaluated on the basis of inductively identified thematic categories in order to subsequently analyze them by content analysis [106] in relation to the contextualization of Baton Rouge. The selected vintages correspond to central development lines of the settlement, such as the boom caused by the petrochemical industry in the 1970s, the years after the depression and before the restrained turnaround at the end of the 1990s, and current trends at the end of the 2010s. The analysis of online-based content such as google hits, Internet videos and images should account for the increased importance of digital offerings in the social construction of analog space. Since the synthetic overview was also in the foreground here instead of focused partial studies, the focus was on a few keywords. The search result lists generated were checked for consistency by submitting the same search query from different IP addresses and computers, whose results, however, showed hardly any or only minor deviations (see in more detail [37]).

The inclusion of Google search results takes into account the softening of spatial scales due to ongoing digitization. The global manifests itself in the local, and the local becomes globally available in fractions of a second via digital offerings, social media, etc. [107,108,109]. In this respect, it seems relevant what impression is created globally by the naming of a settlement, as initial approaches are made without more specific search terms, focusing instead on the settlement itself [110,111]. Such an approach accounts for these developments by examining what impression is created globally by naming a settlement. Such an approximation is initially done without more specific search terms but refers first to the settlement name as a keyword. Further differentiation of the search results in combination with further keywords is a second step, as well as a repetition of the media or newspaper analysis in comparison to, e.g., local newspapers with a focus on certain main topics such as crime, economy, sports, etc., which have already been identified in the national study. This was not done in the study on which this article is based for three reasons: First, the purpose was to test the neopragmatic approach. Second, starting from neopragmatic considerations, it should be shown that regional geographic access can also be achieved with own empirical approaches. Third, by using the methods of triangulation, this neopragmatic regional geography is a synthetic approach, which foregoes a greater “depth of field” (e.g., in the form of extensive use of keywords or large sample sizes) in the triangulated individual investigations in favor of an overall view.

However, this certification can be taken up by further studies in Baton Rouge/Louisiana.

The individuals’ references to Baton Rouge surroundings and society were obtained under a social constructivist framework through qualitative interviews with Baton Rouge residents [112]. The selection of the interview partners consisted essentially of two focus groups: persons residing in Baton Rouge without a professional or volunteer connection to Baton Rouge (13 persons), but with different sociodemographic characteristics such as ethnicity, age (approx. 20 to 75 years), gender (14 male, 6 female) as well as experts on Baton Rouge with different professional or volunteer activities, who are particularly responsible for the city due to their fields of activity (administration/education; 7 persons). While people with a professional or volunteer background in Baton Rouge were specifically contacted and asked for an interview, the acquisition of interview partners, especially for people living in Baton Rouge, was done in an open process. The transcribed interviews were then subjected to software-based analysis based on the content analytic procedure of Mayring [106].

Individual access to the Baton Rouge physical substrate, theoretically oriented on phenomenology, was supplemented by phenomenological walks, involving documentation of our experiencing the surroundings and their changes along longer streets (Government Street, Florida Street/Boulevard, Plank Road) whereby the methods used here are already known, as, for example, to phenomenological approaches with Jacobs, Tuan or Wylie (see [113,114,115,116,117]). The focus on the named streets is based first, on Florida Street/Blvd as the first central transportation axis as a feeder to downtown Baton Rouge and the city’s social equator, and its southern inverse counterpart of Government Street as its parallel street; and Plank Road as one of the central transportation axes in the less privileged northern part of the city (see for the schematic representation of the research design on neopragmatic approaches in terms of theoretical framing and methodological approach Figure 2).

It is precisely within these approaches where the researcher’s subjective component is important that regional (continental Europe) and professional (geography, sociology, political science, linguistics) aspects have a clear influence on interpreting and evaluating Baton Rouge. However, as neo-pragmatically oriented regional geography does not aim at an “objective and unambiguous description of space”, rather accepting contingencies and valuing them as constitutive access to spaces, such a subjective component is an essential element of the scientific approach to Baton Rouge.

4. Historical Aspects of Regional Development

The name “Baton Rouge” dates back to Pierre le Moyne, Sieur D’Iberville, and his brother Bienville. A 1699 expedition took them up the Mississippi, where they saw a red pole (some proclaim a large cypress) on the site of the present town, from which they ascribed this topographical name to the terraced terrain with its steep bank shouldering the Mississippi. In 1721, the first permanent European settlement was established, the D’Artaguette brothers’ farm. However, until the 18th century aged into the 19th, the settlement efforts of the French, Spanish, and English (as interchanging colonial powers) remained ineffective [40,42]. Only in the first decade of the 19th century did the settlement attain certain central-local importance [43].

After an intermezzo as part of the independent state of West Florida, Louisiana became a US state in 1812, making Baton Rouge a US city. The liberal economic order of the United States intensified trade and agriculture. Resultingly, Baton Rouge developed into a regionally important trade center until the American Civil War. In 1850, the city became the seat of the Louisiana Legislature, which increased its political importance while also providing an impetus for developing both population and economy [43,118]. Although direct effects of the civil war on the city remained moderate, the indirect effects were considerable: Trade collapsed, the liberation of slaves changed the social and economic conditions fundamentally, and Baton Rouge temporarily lost its political significance (partial destruction of the Old Louisiana State Capitol during the battle and the Reconstruction era). In 1879, the Louisiana constitution established Baton Rouge as the capitol. As the 19th century ended, Baton Rouge grew sufficiently to make a tram lucrative (albeit only a ring-shaped, single-track line; now long abandoned; [40,42,119,120]).

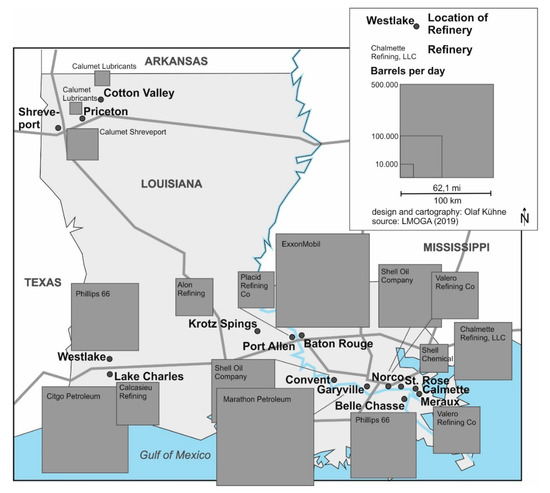

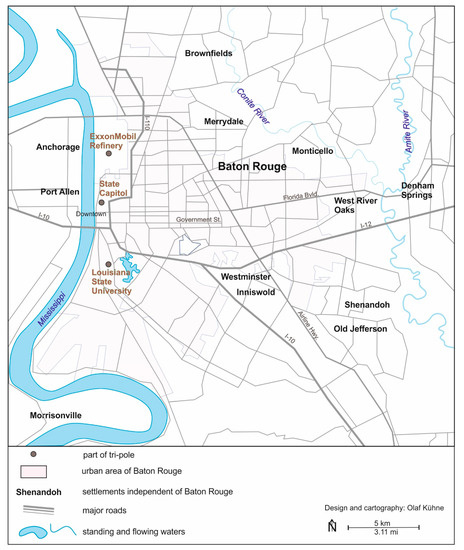

From 1900 to 1930, Baton Rouge underwent fundamental changes: In 1909, Standard Oil built a refinery north of downtown. This heralded Baton Rouge’s accelerated industrialization and continues to conjoin Baton Rouge with the petrochemical industry. To this day, Baton Rouge remains a major site of the petrochemical industry in southern Louisiana (see Figure 3). The complete transformation process left “few elements of the 19th century city intact” [43]. In the 1920s, the Louisiana State University (LSU) campus was established in the south of the city and repeatedly expanded (its predecessor was moved to Baton Rouge as early as 1869, making do with converted buildings, especially military, until the 1920s; [121]). With the construction of the LSU campus, Baton Rouge developed into a “tripolar agglomeration”—the petrochemical industry, state government, and LSU (Figure 4). This tripole dominates the city today, although its importance has shifted to the detriment of the petrochemical industry. A small town, which was only partially elevated from its provinciality by its role as the state capitol, had become a center of petrochemistry and regional education.

Figure 3.

Baton Rouge as the site of the petrochemical industry in southern Louisiana; and daily production of the refineries in Louisiana in January 2017 (own presentation according to [122]).

Figure 4.

The three poles of development in Baton Rouge (own illustration).

Compared to similar-sized cities, Baton Rouge development in the mid-20th century has some specific features that distinguished the city [43,123]:

- (1)

- The especially large areas used by industry and public administration;

- (2)

- The central business district is comparatively small in area and functional importance;

- (3)

- The low level of transportation infrastructure resulted in a comparatively polycentric development structure. This development structure is oriented towards the major employers of the “tripole”;

- (4)

- The rapid city growth in the first decades, especially in the mid-20th century (Figure 5), was driven mainly by investors. The influence of minimal spatial planning resulted in a particularly heterogeneous structure of land-use.

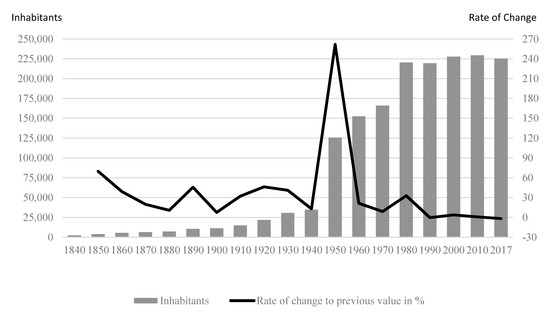

Figure 5. The population evolution of Baton Rouge and rate of change (own illustration according to [121]).

Figure 5. The population evolution of Baton Rouge and rate of change (own illustration according to [121]).

The 1950s and 1960s were characterized—after the oil demand-inducing world War II boom—by steady economic and population growth, including intensive suburbanization, especially white population groups with a higher symbolic capital endowment [124]. Louisiana’s dependence upon the oil market in general, and Baton Rouge specifically, became painfully clear in the 1980s. After the 1970s oil boom, the low oil prices of the 1980s impacted intensely: This impacted residents and petrochemical companies, directly as a result of employee layoffs, and also indirectly through tax revenue loss upon which the State of Louisiana was heavily dependent. Subsequently affecting the other two poles of development that were tax-financed—the Louisiana government and the LSU system. Population growth in the city core stagnated, and suburban areas around the city also showed signs of subdued development (Figure 5). Baton Rouge’s downtown development had largely come to a standstill, but this, together with a growing appreciation of history, made it possible to preserve the buildings’ historic fabric after almost a century of intensive transformation (Figure 6; [40,42,122]).

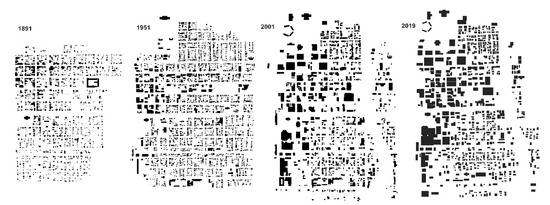

Figure 6.

Figure-ground diagrams of downtown and adjacent Baton Rouge areas for 1891, 1951, 2001, and 2019 (for the years 1891, 1952, and 2001 according to Desmond et al. (2005); for the year 2019: own result based on Google Maps orthophotos). In the nearly thirteen decades under consideration, increasing coarseness of building structure becomes clear. The comparison between the structures of the first two years and the last two years of the study clearly shows the impact of Interstate 110 construction (own illustration [37]).

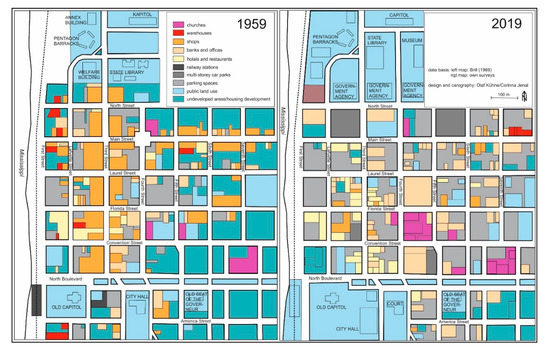

Between 1959 and 2019, downtown land-use was also subject to fundamental change: Third Street lost its function as a shopping area, banks and offices gained importance, public land-use in the north (state) and south (city and Parish) expanded significantly, parking garages were built, especially north of the study area. Overall, however, large downtown sections are still undeveloped and used as parking lots. This downtown structural change is partly due to a general process of “classical downtowns” losing importance, yet has Baton Rouge-specific reasons: Whereas the downtown development was conveniently located near the port and the train station, neither exists now. Remaining is an eccentric location of the downtown “center” on the western district edge, which effectively supported the formation of subcenters (on Government Street, also Perkins Road) and shopping malls (Figure 7; [125,126]).

Figure 7.

The land use of the downtown area comparison, 1959 and 2019 (own illustration [37]).

The consequences of dependence upon the petrochemical industry, combined with the ongoing reluctance to manage the community development administratively, became clear during the Exxon refinery explosion on 23 December 1989: An unusually severe frost plus insufficient technical precautions at the refinery triggered this. The explosion killed two workers plus caused massive damage to adjacent residential properties. Exxon responded with a type of “private land-use planning”, buying up the real estate close to the plant and demolishing the acquired buildings (Figure 8; [37,40,127,128]).

Figure 8.

The layout west of the Exxon site in February 2019, with the acquisition and demolition of buildings, the layout west and east of Interstate 110 is in stark contrast (own illustration [37]).

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina brought numerous New Orleans refugees to the city, combined with emergency shelters, traffic chaos, and the supporting solidarity (eventually overwhelming) of Baton Rouge residents. Not all New Orleanians returned home, which brought a restrained population surge, intensifying the rivalry between the two Louisiana metropolises [40]. On the whole, the community development in the Baton Rouge metropolitan region today is shaped by a simultaneity of centrifugal and centripetal forces: There are clear efforts to revitalize the downtown area by increasing residents, development of restaurants and hotels, offices, etc., concurrently, there are also clear efforts to develop the city’s infrastructure. Hitherto unincorporated suburban communities of East Baton Rouge Parish are making efforts to incorporate (currently in the south: St George), ultimately to be able to reduce tax burdens for the proposed community residents. This makes financing the public school system difficult for the districts east of the ExxonMobil refinery that are especially affected by the gradual de-industrialization [129,130,131,132,133].

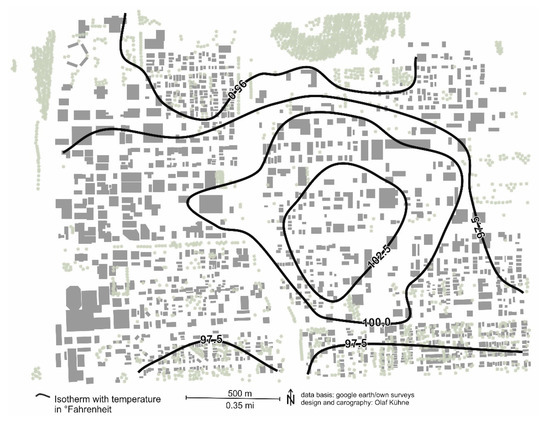

There exists a predominantly African American inhabited triangular area bounded by Interstate 110, to the west, Florida Street/Boulevard, to the south, and Airline Highway, to the east-northeast, that is affected by poverty, a low level of education and a low-density of educational institutions, as well as low availability of (healthy) food stores, scarcely available dining establishments, and impacted by limited mobility (low availability of cars) [134,135,136,137]. According to our own measurements, a maximum urban overheating area can be found here, in addition to the heavily paved downtown area: In September 2019, the equivalent temperature here in the metropolitan areas at night was up to 15 °F above the suburban communities, and during the day a temperature difference of around 15 °F compared to the neighborhoods south of Government Street, which is largely an outcome of reduced tree population compared with community areas possessing a population with a higher symbolic capital endowment. Individual possibilities for protection against heat (air conditioning) are reduced because of the limited economic capital (Figure 9). Synthesizing these findings, we can designate a “triangle of reduced life chances”. The Plank Road phenomenological walk, which cuts through this area, encountered indicators of decline everywhere, dilapidated buildings, partially destroyed advertising installations still heralding the prosperity prior to de-industrialization, run-down pedestrian walkways now unusable, as well as a dog skeleton on the side of the road, while also showing isolated indicators of revitalization—newly opened shops. The noon-time atmosphere was peaceful, cautiously friendly, even if bullet holes in building facades created a certain tension [37,138].

Figure 9.

The distribution of equivalent temperature in downtown and adjacent areas of Baton Rouge on 12 September 2019, measured between 13:50 and 15:45 (own measurements) (own illustration [37]).

Today, Baton Rouge shows typical characteristics of postmodern settlement developments [139,140,141,142,143,144], such as fragmentation, de-surbanization, the dominance of economic exploitation logics, but also beginnings of re-urbanization, appreciative preservation of historic building fabric and a tentative waterfront development opening up the city to the Mississippi River, in the form of a waterfront promenade (whose access is partially blocked by railroad tracks) and the construction of apartment buildings near the shore. The spatial structure of Baton Rouge appears dissolved in a pastiche [145,146,147] of different building and use intensities, neighborhoods simulating urbanity in otherwise suburban structures, the juxtaposition of neighborhoods inhabited by people with high and low endowments of symbolic capital (in Bourdieu’s sense [124]), different ethnicities, and different lifestyles. This “islandization” of neighborhoods is driven by a transport infrastructure that has not been intensively developed to date [37].

5. The Construction of Baton Rouge in Media and by Residents

With the aim of capturing the Baton Rouge social construction more precisely, we used a medium that increasingly shapes patterns of perception, interpretation, and evaluation: the Internet. Here we examined the first three Google hit pages—hit pages beyond that amount are usually not explored in common searches [148]. Furthermore, we analyzed the first 100 Google image hits (comparable studies show that more images lead to irrelevant hits and that these hits on the search term do not bring useful findings; [149]). Additionally, we evaluated 55 assessable YouTube videos pertinent to Baton Rouge (other video hits were unrelated to Baton Rouge). Furthermore, to investigate the national mass media response to Baton Rouge, we analyzed the New York Times (1978, 1998, and 2018 volumes) seeking articles involving Baton Rouge. The evaluations were conducted from March through May 2019, using computers that did not allow influencing by previous searches. These were accompanied by 20 qualitative guideline-based interviews focusing on Baton Rouge’s life and development.

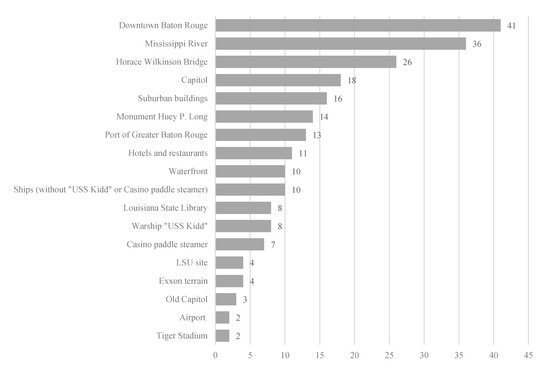

The Google hits primarily referenced tourist attractions and restaurants local to Baton Rouge, without mentioning Baton Rouge’s nightlife. The high crime and HIV rates in Baton Rouge were only mentioned on the German Wikipedia page—not the English one. It is noticeable in Wikipedia entries of both languages that a detailed examination of Baton Rouge (compared to New Orleans) is lacking. The Google hits created the impression of a tranquil small town in the southern states. An image that is only partially replicated by Google image hits (Figure 10). Here, Baton Rouge is staged dominantly as an urban settlement with primarily downtown photos being found, but this may also be a result of the main attraction, the State Capitol building, providing the visitor a free elevated panoramic platform overlooking the urban area, especially this adjacent downtown area plus the Mississippi River and the Horace Wilkinson Bridge (25% of the examined photos are taken from the Capitol building point of view). Remarkable is the low human presence in Baton Rouge photos (only 14% of photos show people, but should be relativized considering the dominance of panorama photos from the Capitol building). In keeping with the dictum of Gerhard Hard [150], it is often more worthwhile for geographical analysis to examine what is not visible; accordingly, the suburban settlements (even those with a high presence in guidebooks, such as Beauregard or Spanish Town), as well as Baton Rouge neighborhoods inhabited by African Americans, have been left out.

Figure 10.

The thematic foci of the 100 Baton Rouge images examined (own survey and representation).

This topic moves into focus with the evaluated videos. In addition to life in the African American neighborhoods, the subject matter of a panoramic tourist overlook (especially downtown hotels, restaurants, Horace Wilkinson Bridge, Mississippi River, moreover, plantation buildings and the swamps are more frequently presented) and music videos (whereby Baton Rouge usually appears here more as any interchangeable southern city) are also included. In these videos, almost without exception, persons of white skin color are present, which is inverse in the videos of the category “living in Black neighborhoods”. Whites appear here either in an assimilated form (which is explicitly pointed out) or as police officers. Particularly policemen, state authorities in general, are presented as the “other”, something that should be avoided for reasons of racist attacks. Overall, this video category predominantly portrays verbal and physical violence or violence is thematized (on YouTube channels, being modeled on classic news programs). Accompanying violence, drugs including their distribution and consumption, are often presented in an affirmative way; the same applies to (male protagonists) wads of cash, gold jewelry, and customized cars. Women play a marginal role in the videos when they do appear, mostly as victims of violence. An exception is the video of a young black woman in her summer dress following the shooting of a black man lying on the ground by a policeman, calmly opposing heavily armed police officers, only to be arrested, thus again underscoring the theme of being victims.

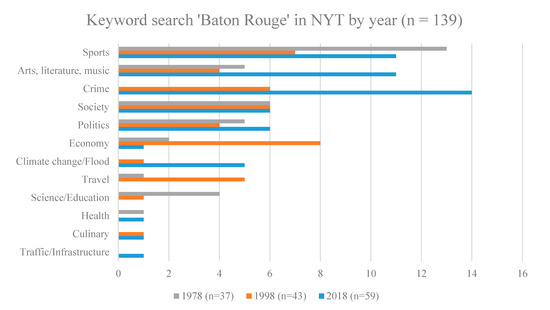

In the New York Times articles, too, the issue of Baton Rouge violence has recently become more important than other issues (Figure 11). Across all evaluated articles, depictions of poverty, social grievances, mismanagement, and especially ethnic-social segregation and violence involving fatal shootings focused on police involvement dominates. The petrochemical industry, omnipresent in Baton Rouge, appears less frequently as with references to the Mississippi River. This, in turn, can be interpreted as indicative of the mass media system, whose binary code is actuality vs. non-actuality, thereby propagating longer-lasting processes and persistencies as a stereotypical background [151]. That such a stereotypical connotation of Baton Rouge with violence (somewhat more subdued with corruption) is already quite well established is shown both by the evaluation of YouTube videos and the New York Times coverage, plus in music titles related to Baton Rouge, available via Amazon Music and YouTube (n = 45): A comparison between titles released before the year 2000 and from 2000 to present shows a clear shift from interpersonal (love) relationships and leisure-related aspects of life to those of crime, drugs, and violence. This shift goes hand-in-hand with the change of genre—away from country and blues and towards rap music.

Figure 11.

Keyword search for “Baton Rouge” in the NYT (New York Times) online archive for the years 1978, 1998, and 2018 by category and year in absolute numbers; accessed in May 2019.

In addition, qualitative interviews with residents of Baton Rouge were conducted to illustrate individual living environments: In the interviews, themes such as crime, poverty, and the divided city is explicitly expressed and thematized. Notably, that there are “two separate Baton Rouges” that live “next to each other”, but not “together”. Initiatives for an integration of the two Baton Rouges are named, but also hostility from those with conservative preferences is reported as being directed towards those involved in these initiatives. The environmental pollution in Baton Rouge, attributed primarily to the petrochemical industry, is more problematic. Another is the traffic situation in Baton Rouge, an ineffectively developed public transport system compounded by congested and dilapidated roads. In resident’s descriptions, Baton Rouge is an unexciting, peaceful aggregate of neighborhoods without a real center and special regional landmarks. Interestingly, the Mississippi River, which could perform this function, gains little mention in the interviews. Overall, friendliness, helpfulness, and hospitality in Baton Rouge were positively emphasized, and the possibility of quickly acquiring intensive social networks, which would then help people only “passing through” (for example, to study or for a job) to settle permanently.

Thus, the Internet-related research and interview result only moderately reveal a congruent Baton Rouge depiction. Contrastingly, ethnic and symbolic capital segregation plus associated opportunity inequality are addressed with strongly divergent intensity. There is a tendency for conflicts (both the video presentations and often the interviews) to be negotiated on a personal rather than systemic level (in the sense of [152,153]). Concurrently, a tendency for the positive assessment of the living situation (friendliness, commitment, etc.) exists, while the systemic level (public transport, the decay of the downtown area, etc.) is criticized.

6. Conclusions

The development of metropolitan Baton Rouge expresses general processes such as industrialization, post-industrialization, and suburbanization, among others, which are modified by strong inherent logic [28]. For instance, the low influence of a planning administration, but also the specific physical and spatial characteristics, such as the river bank terracing dictating the location of the downtown area. Respectively, the importance of regional geography sensitivity to scale, as advocated by the “new regional geography”, also found in the neopragmatic regional geography, is evident here.

Baton Rouge is a city of contrasts. Especially the “triangle of diminished life chances” striking contrast to the Arcadian Baton Rouge, south of Florida Street/Boulevard, with its enhancing tree density and “old south” simulation. The media representation clarifies this Arcadian contrast, almost encoded in binary, with the African American Baton Rouge of poverty, drug consumption, and violence. The interchange between these two is rare—as the interviews also show. The result is massive unequal life chances distribution, magnified by suburban incorporation attempts such as St. George’s. Consequently, Baton Rouge cannot be characterized as only a tripole metropolis oriented around LSU, the petrochemical industry, and state capitol. Contemporaneously, there is a “bi-pole” orientation with an above-average symbolic capital and life chances “white pole” starkly contrasting a “black pole” of below-average symbolic capital and life chances. This unequal distribution of life chances is problematical, especially regarding the goal of the state and society’s task to increase individual life chances, as inspired by Ralf Dahrendorf. Indicative is an inadequate technical and social infrastructure.

Baton Rouge can be considered an extreme example of postmodern settlement development; the spatial structures are extremely fragmented, the distribution of living opportunities polarized. This not only affects the opportunities to participate in education, to participate in transportation, the accessibility to food but also extends to urban climatic living conditions, which are more favorable in parts of the city inhabited by people with a high endowment of symbolic capital than where a lower endowment of symbolic capital dominates [138]. If the polarity is assumed between a settlement development driven by politics and administration on one hand and private, especially economic interests, but also esthetic preferences [154,155,156,157,158], on the other hand, the developments of and in Baton Rouge are to be classified very much on the side of the second pole. This also results in relevance for settlement research in general rather than urban research of and on Baton Rouge in particular: In Baton Rouge, it becomes clear how a metropolitan region develops under extensive abstention of administrative/planning influence, which in this form is a peculiarity even in the United States.

In presenting the results of the Baton Rouge study, we can clearly exemplify the considerably advantageous integration of Internet communication in regional geographic studies since information is generated in ways that are difficult to access using other methods and also assisting in crafting an image of Baton Rouge. Associated is the assessment that a theoretically multiperspective consideration has proven to be worthwhile. The combination of positively framed (quantitative) empiricism and constructively oriented qualitative approaches, including the phenomenological walks, led to a more nuanced understanding of this complex object of research. Respectively, perceptions that regional geography alone has the task of presenting results can also be contradicted. Particularly concerning fragmentary studies of a region to date, such a multimethodological approach can produce results enabling a multifaceted regional picture, as with Baton Rouge. However, with the reservation that such a neopragmatic regional geography cannot replace more detailed investigations since its goal is a synthetic, not in-depth, examination, which is also the aim of the scope of the various individual investigations. Whether the developed approach of neopragmatic regional geography is also suitable for larger spatial units, such as Louisiana as a whole, needs to be examined.

In brief: This article has shown that the neopragmatic approach can provide a basis for (further) regional geographic studies and can also serve as a basis for a triangulated empirical approach to regional geographies. In favor of a synthetic overview, the level of detail of the individual sub-studies does not remain widely expanded but provides approaches for a more detailed investigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.K., C.J., Methodology, O.K., C.J., Writing—Original draft preparation, O.K., C.J., Writing—review and editing, O.K., C.J., Visualization, O.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article, with the exception of the interview data, which are not publicly available due to reasons of privacy and assurance of anonymity of the respondents.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chilla, T.; Kühne, O.; Weber, F.; Weber, F. Neopragmatische Argumente zur Vereinbarkeit von konzeptioneller Diskussion und Praxis der Regionalentwicklung. In Bausteine der Regionalentwicklung; Kühne, O., Weber, F., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2015; pp. 13–24. ISBN 978-3-658-02881-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O. Reboot Regionale Geographie–Ansätze einer neopragmatischen Rekonfiguration horizontaler Geographien. Berichte. Geogr. Landeskd. 2018, 92, 101–121. [Google Scholar]

- Eckardt, F. Stadtforschung Gegenstand und Methoden; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014; ISBN 9783658008239. [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou, F. Spatial Complexity. Theory, Mathematical Methods and Applications; Springer Nature: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 9783030596712. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, G. Entwicklungsperspektiven Regionaler Geographie. Würzbg. Geogr. Arb. 2000, 94, 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Paasi, A. The institutionalization of regions: A theoretical framework for understanding the emergence of regions and the constitution of regional identity. Fennia–Int. J. Geogr. 1986, 164, 105–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werlen, B. Länderkunde oder Geographien der Subjekte? Zehn Thesen zum Verhältnis von Regional und Sozialgeographie. In Geographie: Tradition und Fortschritt: Festschrift zum 50jährigen Bestehen der Heidelberger Geographischen Gesellschaft; Karrasch, H., Ed.; Heidelberger Geographische Gesellschaft: Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; pp. 106–125. [Google Scholar]

- Thrift, N. For a new regional geography 2. Progres. Human Geogr. 1991, 15, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. Regional Geography, I. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Kitchin, R., Thrift, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 9, pp. 214–227. ISBN 9780080449104. [Google Scholar]

- Nir, D. Regional geography considered from the systems’ approach. Geoforum 1987, 18, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmén, H. What’s new and What’s Regional in the New Regional Geography? Geogr. Annal. Ser. B Human Geogr. 1995, 77, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guelke, L. Regional Geography. Prof. Geogr. 1977, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, H.; Reuber, P.; Wolkersdorfer, G. Konzepte und Konstruktionsweisen regionaler Geographien im Wandel der Zeit. Ber. Dtsch. Landeskd. 2004, 78, 293–312. [Google Scholar]

- Rorty, R. Objectivity, Relativism, and Truth; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; ISBN 0521353696. [Google Scholar]

- Rorty, R. Consequences of Pragmatism. Essays: 1972–1980; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1982; ISBN 0816610649. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, H. Pragmatism: An Open Question; Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand, D.L. The neopragmatist turn. Southwest Philosop. Rev. 2003, 19, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand, D.L. Pragmatism, neopragmatism, and public administration. Adm. Soc. 2005, 37, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warms, C.A.; Schroeder, C.A. Bridging the gulf between science and action: The “new fuzzies” of neopragmatism. Adv. Nursing Sci. 1999, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahrendorf, R. Lebenschancen. Anläufe zur Sozialen und Politischen Theorie; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 1979; ISBN 3518370596. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, A.C. Life chances and modern poverty. Urb. Des. Int. 2002, 7, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahrendorf, R. Homo Sociologicus. Ein Versuch zur Geschichte, Bedeutung und Kritik der Kategorie der sozialen Rolle, 10. Auflage; Westdeutscher Verlag: Opladen, Germany, 1971; ISBN 3531110810. [Google Scholar]

- Dahrendorf, R. The Modern Social Conflict. The Politics of Liberty; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dahrendorf, R. Class and Class Conflict in Industrial Society; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 1331468329. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, K.R. The Open Society and Its Enemies; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011; ISBN 9780415610216. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, K.R. Alles Leben ist Problemlösen. Über Erkenntnis, Geschichte und Politik; Piper: Munich, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dahrendorf, R. Der moderne soziale Konflikt. Essay zur Politik der Freiheit; Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag: Munich, Germany, 1994; ISBN 3-423-04628-7. [Google Scholar]

- Berking, H.; Löw, M. (Eds.) Die Eigenlogik der Städte–Neue Wege für die Stadtforschung; Campus: Frankfurt, Germany, 2008; ISBN 9783593387253. [Google Scholar]

- Beuka, R. SuburbiaNation. Reading Suburban Landscape in Twentieth-Century American Fiction and Film; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 9781403963406. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, G. (Ed.) The American Landscape. Literary Sources & Documents; Helm Information: Mountfield, Germany, 1993; ISBN 1873403054. [Google Scholar]

- Conzen, M.P. (Ed.) The Making of the American Landscape; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780415950077. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, J.S.; Duncan, N. Landscapes of Privilege. The Politics of the Aesthetics in an American Suburb; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0415946889. [Google Scholar]

- Holzner, L. Stadtland USA: Die Kulturlandschaft des American Way of Life; Justus Perthes Verlag: Gotha, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, R.H. The Place of Landscape: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting an American Scene. Annal. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1997, 87, 660–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Groth, P. (Eds.) Everyday America. Cultural Landscape Studies after J. B. Jackson; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2003; ISBN 0520229614. [Google Scholar]

- Zapatka, C. The American Landscape; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O.; Jenal, C. Baton Rouge–The Multivillage Metropolis. A Neopragmatic Landscape Biographical Approach on Spatial Pastiches, Hybridization, and Differentiation; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, A.M. Historic Neighborhoods of Baton Rouge; The History Press: Charleston, NC, USA, 2010; ISBN 1596298391. [Google Scholar]

- Gleason, D.K.; Brockway, W.R. Baton Rouge. Photographs and Text; Louisiana State University Press: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 1991; ISBN 9780807117156. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigue, S.F.; Phillips, F. Historic Baton Rouge. An Illustrated History, 2nd ed.; Historical Publishing Network, a Ivision of Lammert Incorporated: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2011; ISBN 1935377493. [Google Scholar]

- Hendry, P.M.; Edwards, J.D. Old South Baton Rouge. The Roots of Hope; University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press: Lafayette, LA, USA, 2009; ISBN 9781887366861. [Google Scholar]

- Carleton, M.T. River Capital. An Illustrated History of Baton Rouge; Windsor Publications, Inc.: Woodland Hills, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Brill, D. Baton Rouge, LA.; Aufstieg, Funktionen und Gestalt Einer Jungen Großstadt des Neuen Industriegebietes am Unteren Mississippi; Selbstverlag des Geographischen Instituts der Universität Kiel: Kiel, Germany, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. Chapter 34 Triangulation in Data Collection. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection; Flick, U., Ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2018; pp. 527–544. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K. Triangulation. In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology; Ritzer, G., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J.M. Approaches to Qualitative-Quantitative Methodological Triangulation. Nursing Res. 1991, 40, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jick, T.D. Mixing Qualitative and Quantitative Methods: Triangulation in Action. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. Triangulation; Springer Fachmedien: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011; ISBN 9783531181257. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz, U. Mixed Methods Methodologie, Forschungsdesigns und Analyseverfahren; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014; ISBN 9783531932675. [Google Scholar]

- Wardenga, U. Theorie und Praxis der länderkundlichen Forschung und Darstellung in Deutschland. In Zur Entwicklung des länderkundlichen Ansatzes; Grimm, F.-D., Wardenga, U., Eds.; Selbstverlag: Leipzig, Germany, 2001; pp. 9–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wardenga, U. Von der Landeskunde zur “Landeskunde”. In Der Weg der Deutschen Geographie; Heinritz, G., Sandner, G., Wießner, R., Eds.; Rückblick und Ausblick. Deutscher Geographentag, Potsdam, 1995; Franz Steiner Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 1996; pp. 132–141. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, H.-D. Räume sind nicht, Räume werden gemacht: Zur Genese “Mitteleuropas” in der deutschen Geographie. Eur Reg. 1997, 5, 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, A. The new regional geography in English and French-speaking countries. Progr. Human Geogr. 1988, 12, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrift, N.J. On the Determination of Social Action in Space and Time. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 1983, 1, 23–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. Place and region: Regional worlds and words. Progr. Human Geogr. 2002, 26, 802–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entrikin, J.N. Place and region 2. Progr. Human Geogr. 1996, 20, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. Deconstructing Regions: Notes on the Scales of Spatial Life. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 1991, 23, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorimer, H. Cultural geography: The busyness of being ‘more-than-representational’. Progr. Human Geogr. 2005, 29, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joas, H. Symbolischer Interaktionismus: Von der Philosophie des Pragmatismus zu einer soziologischen Forschungstradition. Köl. Z. Soziol. Sozialpsychol. 1988, 40, 417–446. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, H.-J.; Joas, H.; Wenzel, H. Pragmatismus zur Einführung. Kreativität, Handlung, Deduktion, Induktion, Abduktion, Chicago School, Sozialreform, Symbolische Interaktion; Junius: Hamburg, Germany, 2010; ISBN 3885066823. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, C. Pragmatismus-Umwelt-Raum. Potenziale des Pragmatismus für Eine Transdisziplinäre Geographie der Mitwelt; Franz Steiner Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2014; ISBN 9783515108829. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, C. Von Interaktion zu Transaktion–Konsequenzen eines pragmatischen Mensch-Umwelt-Verständnisses für eine Geographie der Mitwelt. Geogr. Helvetica 2014, 69, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichhart, P. Auf der Suche nach der “dritten Säule”. Gibt es Wege von der Rhetorik zur Pragmatik? In Möglichkeiten und Grenzen Integrativer Forschungsansätze in Physischer Geographie und Humangeographie; Müller-Mahn, D., Wardenga, U., Eds.; Selbstverlag Leibniz-Institut für Länderkunde e.V.: Leipzig, Germany, 2005; pp. 109–136. ISBN 3860820532. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, C. Materie oder Geist? Überlegungen zur Überwindung dualistischer Erkenntniskonzepte aus der Perspektive einer Pragmatischen Geographie. Berichte. Geogr. Landeskd. 2009, 83, 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kersting, P. Geomorphologie, Pragmatismus und integrative Ansätze in der Geographie. Berichte. Geogr. Landeskd. 2012, 86, 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, K.R. Objektive Erkenntnis. Ein Evolutionärer Entwurf; Hoffmann und Campe: Hamburg, Germany, 1973; ISBN 3-455-09088-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O. Die Landschaften 1, 2 und 3 und ihr Wandel: Perspektiven für die Landschaftsforschung in der Geographie–50 Jahre nach Kiel. Berichte. Geogr. Landeskd. 2018, 92, 217–231. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, K.R. Auf der Suche nach Einer Besseren Welt Vorträge und Aufsätze aus Dreißig Jahren; Piper Verlag: Munich, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O. Landscape Conflicts: A Theoretical Approach Based on the Three Worlds Theory of Karl Popper and the Conflict Theory of Ralf Dahrendorf, Illustrated by the Example of the Energy System Transformation in Germany. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühne, O.; Berr, K.; Schuster, K.; Jenal, C. Freiheit und Landschaft Auf der Suche nach Lebenschancen mit Ralf Dahrendorf; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Weichhart, P. Die Räume zwischen den Welten und die Welt der Räume. In Handlungszentrierte Sozialgeographie: Benno Werlens Entwurf in kritischer Diskussion; Meusburger, P., Ed.; Steiner-Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 1999; pp. 67–94. ISBN 3-515-07613-1. [Google Scholar]

- Zoglauer, T. Geist und Gehirn. Das Leib-Seele-Problem in der Aktuellen Diskussion; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen, Germany, 1998; ISBN 3-525-03322-2. [Google Scholar]

- Beckermann, A. Analytische Einführung in die Philosophie des Geistes; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1999; ISBN 9783110204247. [Google Scholar]

- Brüntrup, G. Das Leib-Seele-Problem. Eine Einführung; Kohlhammer: Stuttgart, Germany, 1996; ISBN 3-17-014005-1. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, K. Realism and the Aim of Science. From the Postscript to The Logic of Scientific Discovery; Hutchinson: London, UK, 1983; ISBN 0091514509. [Google Scholar]

- Berking, H. StadtGesellschaft: Zur Kontroverse um die Eigenlogik der Städte. Leviathan 2013, 41, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S. Eigenlogik der Städte. In Handbuch Stadtsoziologie; Eckardt, F., Ed.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012; pp. 289–309. ISBN 978-3-531-94112-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O.; Schönwald, A. San Diego. Eigenlogiken, Widersprüche und Hybriditäten in und von ‘America’s Finest City’; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2015; ISBN 978-3-658-01719-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, A. Der Blickpunkt von niemand besonderen. In Die Renaissance des Pragmatismus: Aktuelle Verflechtungen Zwischen Analytischer und Kontinentaler Philosophie; Sandbothe, M., Ed.; Velbrück: Weilerswist, Germany, 2000; pp. 59–77. ISBN 9783934730243. [Google Scholar]

- Nassehi, A. Die letzte Stunde der Wahrheit. Kritik der komplexitätsvergessenen Vernunft; Sven Murmann Verlagsgesellschaft: Hamburg, Germany, 2017; ISBN 3946514588. [Google Scholar]

- Chilla, T.; Kühne, O.; Neufeld, M. Regionalentwicklung; Ulmer: Stuttgart, Germany, 2016; ISBN 3-8252-4566-7. [Google Scholar]

- Boeckler, M. Digitale Geographien: Neogeographie, Ortsmedien und der Ort der Geographie im Digitalen Zeitalter. Available online: https://www.uni-frankfurt.de/50886768/Boeckler_2014_Digitale_Geographien.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2019).

- Edler, D.; Lammert-Siepmann, N. Approaching the Acoustic Dimension in Cartographic Theory and Practice. Metacarto–semiotics 2017, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Henshaw, V. Urban Smellscapes. Understanding and Designing City Smell Environments; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 9780203072776. [Google Scholar]

- Kazig, R.; Weichhart, P. Die Neuthematisierung der materiellen Welt in der Humangeographie. Berichte. Geogr. Landeskd. 2009, 83, 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Hasse, J. Atmosphären der Stadt. Aufgespürte Räume; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2012; ISBN 978-3868591255. [Google Scholar]

- Gailing, L. Landschaft und produktive Macht. In Landschaftswandel–Wandel von Machtstrukturen; Kost, S., Schönwald, A., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2015; pp. 37–51. ISBN 978-3-658-04330-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O. Kritische Geographie der Machtbeziehungen–Konzeptionelle Überlegungen auf der Grundlage der Soziologie Pierre Bourdieus. Geogr. Revue 2008, 10, 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Paasi, A. The region, identity, and power. Proced Soc.Behav. Sci. 2011, 14, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, J. Diskursethik–Notizen zu einem Begründungsprogramm. In Moralbewußtsein und Kommunikatives Handeln; Habermas, J., Ed.; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 1983; pp. 53–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann, W. Begründung. In Handbuch Ethik 3, updated ed.; Düwell, M., Hübenthal, C., Werner, M.H., Eds.; J.B. Metzler: Stuttgart, Germany, 2011; pp. 319–325. ISBN 978-3476023889. [Google Scholar]

- Stegmüller, W. Probleme und Resultate der Wissenschaftstheorie und analytischen Philosophie, Bd. IV: Personelle und statistische Wahrscheinlichkeit: 2. Halbband: Statistisches Schließen–Statistische Begründung–Statistische Analyse. Biom. Z. 1975, 17, 133. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E.W. Seeking Spatial Justice; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780816666676. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The Right to the City. New Left Rev. 2008, 27, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E. The city and spatial justice. Justice Spatiale/Spatial Justice 2009, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Dahrendorf, R. Auf der Suche nach Einer Neuen Ordnung. Vorlesungen zur Politik der Freiheit im 21. Jahrhundert, 4th ed.; C. H. Beck: Munich, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lindner, C. Freiheit und Fairness. In Freiheit: Gefühlt–Gedacht–Gelebt: Liberale Beiträge zu Einer Wertediskussion; Rösler, P., Lindner, C., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009; pp. 17–28. ISBN 9783531163871. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, L. Freiheit Gehört Nicht nur den Reichen. Plädoyer für Einen Zeitgemäßen Liberalismus; C. H. Beck: Munich, Germany, 2013; ISBN 9783406659331. [Google Scholar]

- Dahrendorf, R. Die Chancen der Krise. Über die Zukunft des Liberalismus; Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt: Stuttgart, Germany, 1983; ISBN 3421061483. [Google Scholar]

- Dahrendorf, R. Der Wiederbeginn der Geschichte. Vom Fall der Mauer zum Krieg im Irak; C. H. Beck: Munich, Germany, 2004; ISBN 3-406-51879-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O.; Leonardi, L. Ralf Dahrendorf. Between Social Theory and Political Practice; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, B.L. Videographic geographies: Using digital video for geographic research. Progr. Human Geogr. 2011, 35, 521–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühne, O.; Weber, F. Der Energienetzausbau in Internetvideos–eine quantitativ ausgerichtete diskurstheoretisch orientierte Analyse. In Landschaftswandel–Wandel von Machtstrukturen; Kost, S., Schönwald, A., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2015; pp. 113–126. ISBN 978-3-658-04330-8. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, M.; Phillips, L. Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method; SAGE: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Statistiken zur New York Times Company. Available online: https://de.statista.com/themen/2554/new-york-times-company/ (accessed on 8 July 2019).

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken, 10, Neu Ausgestattete Auflage; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. Was ist Globalisierung? Irrtümer des Globalismus–Antworten auf Globalisierung, 1. Auflage; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 1997; ISBN 3518409441. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, R. Glocalization: Time-Space and Homogeneity-Heterogeneity. In Global Modernities; Featherstone, M., Lash, S., Robertson, R., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 1995; pp. 25–44. ISBN 9780803979482. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. Weltrisikogesellschaft. Auf der Suche nach der verlorenen Sicherheit; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 2007; ISBN 978-3518414255. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, D. Google Now Handles at Least 2 Trillion Searches per Year. Available online: https://searchengineland.com/google-now-handles-2-999-trillion-searches-per-year-250247 (accessed on 20 May 2019).

- Pan, B.; Hembrooke, H.; Joachims, T.; Lorigo, L.; Gay, G.; Granka, L. In Google We Trust: Users’ Decisions on Rank, Position, and Relevance. J. Comp. Med. Commun. 2007, 12, 801–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misoch, S. Qualitative Interviews; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2015; ISBN 3-11-034810-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kazig, R. Typische Atmosphären städtischer Plätze: Auf dem Weg zu einer anwendungsorientierten Atmosphärenforschung. Alte Stadt 2008, 35, 148–160. [Google Scholar]

- Wylie, J. A single day’s walking: Narrating self and landscape on the South West Coast Path. Trans. Inst. Brtish Geogr. 2005, 30, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1992; ISBN 9780679741954. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Surface Phenomena and Aesthetic Experience. Annal. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1989, 79, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes and Values; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, M.L. Some Aspects of the Social History of Baton Rouge from 1830 to 1850; Eigenverlag: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, C.V. Origins of the New South, 1877–1913. A History of the South; LSU Press: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 1981; ISBN 0807158208. [Google Scholar]

- Draughon, R., Jr. Down by the River. A History of the Baton Rouge Riverfront; US Army Corps of Engineers, New Orleans District: New Orleans, LA, USA, 1998.

- Ruffin, T.F. Under Stately Oaks. A Pictorial History of LSU, Revised Edition; Louisiana State University Press: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2006; ISBN 9780807132111. [Google Scholar]

- World Population Review. Baton Rouge, Louisiana Population 2019. Available online: http://worldpopulationreview.com/us-cities/baton-rouge-population/ (accessed on 1 July 2019).

- Bartholomew, H. The 25 Year-Parish Plan for Metropolitan Baton Rouge. Louisiana; Eigenverlag: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 1945; pp. 1945–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. La Distinction: Critique Sociale du Jugement; Editions de Minuit: Paris, France, 2016; ISBN 2707337218. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O.; Jenal, C. Stadtlandhybride Prozesse in Baton Rouge: Von der klassischen Downtown zur postmodernen Downtownsimulation. In Landschaft als Prozess; Duttmann, R., Kühne, O., Weber, F., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; in diesem band. [Google Scholar]

- Kühne, O.; Jenal, C. Baton Rouge (Louisiana): On the Importance of Thematic Cartography for Neopragmatic Horizontal Geography. KN J. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burby, R.J. Baton Rouge: The Making (and Breaking) of a Petrochemical Paradise. In Transforming New Orleans and Its Environs: Centuries of Change; Colten, C.E., Ed.; University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2000; pp. 160–177. ISBN 9780822941347. [Google Scholar]

- Colten, C.E. An Incomplete Solution: Oil and Water in Louisiana. J. Am. History 2012, 99, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlin, S. Louisiana Lawmakers, Over Objections from Mayor Broome, pass St. George Transition Bill. Available online: https://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/news/politics/legislature/article_cee67e14-83c1-11e9-8eaf-3f731f98791a.html (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- McCollister, R. Publisher: St. George Could Have Been Avoided. Available online: https://www.businessreport.com/opinions/st-george-baton-rouge (accessed on 13 December 2019).

- Jones, T.L. Here’s Why St. George’s Effort in Baton Rouge Will Happen, Leaders of Similar Project Say. Available online: https://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/news/article_1edd239e-2afa-11e9-ac4c-8bf177e0e1a2.html (accessed on 13 December 2019).

- The City of St. George. The City of St. George, Louisiana. Available online: http://www.stgeorgelouisiana.com/ (accessed on 13 December 2019).

- Harris, A. The New Secession: Residents of the Majority–White Southeast Corner of Baton Rouge Want to Make Their Own City, Complete With its Own Schools, Breaking Away from the Majority–Black Parts of Town. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2019/05/resegregation-baton-rouge-public-schools/589381/ (accessed on 13 December 2019).

- Antipova, A. Land Use, Individual Attributes, and Travel Behavior in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Available online: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3450/ (accessed on 13 June 2019).