1. Introduction

Rosengård, a city district in East Central Malmö, is currently implementating a Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) project named Culture Casbah. In the project, physical planning- with the new train station as the focus is paired with the vision of integration at every level [

1]. It also aims at improved living conditions in the area and for the whole of Malmö in the longer term. The district of Rosengård is the result of powerful action in the mid-1960s on behalf of the government, parliament, and local municipalities to build a million homes in ten years [

2]. Shortly after its completion, it was stigmatized and despite numerous attempts at urban transformation, during the 50 years since Rosengård was built, this stigma has prevailed [

3]. The area is also a multi-ethnic district with high unemployment rate and is infamous for its low socio-economic status and vulnerability. Listerborn (2019) explains, “the problems of Rosengård are partly related to housing conditions, but also more structural problems such as income inequalities and quality of schools”. In November 2016, after a lengthy debate about several replicas, the City Council approved the proposal for Culture Casbah, which is a space between the new train station and the center of Rosengård. This subarea is currently home to 5069 people living in 1660 apartments served by 126 stairwells [

1]. Driven by the motivation of social integration, the development is pursuing the goal of social sustainability, which has been lauded by the well-founded conclusions of the

2016 Commission for a Socially Sustainable Malmö. The redevelopment process in Rosengård concludes a new train station, renovation of 1660 apartments as well as construction of a 22-story tower, 200 new homes, and 30 premises with the name of Culture Casbah project. The mayor of Malmö claimed that Culture Casbah will help more people both work in and visit Rosengård thus creating the living conditions that characterize an attractive district [

4]. Policymakers hope that by giving Rosengård a station, they will create an area with good accessibility that can serve as an active meeting place for trade, culture, and social interaction. Furthermore, by extension, the now-planned investments will lead to further investments, which in turn will contribute to continued housing construction, increased growth, and development, and consequently, the area can become a mixed district.

In recent years, there has been a growing debate on contradictory consequences of transit-led investments in low-income urban districts. Since Calthorpe [

5], codified TOD as a neo-traditional guide to sustainable community design as well as a community design theory that promises to address a myriad of social issues, there have been many scholars praising the positive socio-economic achivements due to TODs. At the same time, specifically in the last ten years, some researchers have criticized this way of urban development. Rayle claimed that whereas public transit is often seen as benefiting low-income and minority populations, in many cities, the threat of displacement has motivated equity advocates to challenge TOD and other transit-investment initiatives [

6]. Dawkins and Moeckel [

7] call this phenomenon

transit-induced gentrification. At the same time, empirical research has so far found little evidence that gentrification leads to displacement, and some studies even suggest that gentrification reduces residential mobility. Others such as Hamnett [

8], also failed to find substantial evidence of displacement leading some to suggest that gentrification can sometimes generate benefits with minimal displacement [

9].

Rosengård’s TOD has met with occasional disagreement by equity advocates and certain politicians as well as some Malmö residents. One example is when one hundred Malmö residents protested against the plan to sell public housing in Rosengård to finance the massive Culture Casbah construction project [

9]. Equity advocates argue that the resident’s risk becomes worse with a private landlord, as this would not include the municipally owned MKB’s social remit. They also claim that Rosengård is home to many low-income residents, and the possible rent increase may lead to displacement. Some politicians are concerned about rising rent levels and also criticize the municipality’s decision to hand over a 75 percent stake in the apartments just a year before the new train station is scheduled to open, which could see these same apartments rise in value [

10]. For example, the Sweden Democrats criticized the plan and argued that a physical building will not solve the problems there and that Rosengård needs security and proper schooling, not risky projects.

These contradictory issues regarding the massive investment in this immigrant disadvantaged neighborhood allowed us to discuss the possible consequences of this neighborhood’s change process. We aimed to discuss the issue by bringing together previously disparate literature on these contradictions and discuss policymakers’ “hopes” and critics’ “concerns” using empirical evidence from the area. The central hypothesis of this article is that TOD in Rosengård may result in gentrification, the current low-income resident’s displacement, and polarization. This research discusses three apparent debates: (1) the gentrification–displacement debate, (2) the affordability paradox of TOD, and (3) the segregation–integration debate. These debates bring up some main questions: (1) What evidence can be found of gentrification and displacement in the target area? How do residents interpret the new investments as a positive change and an economic-opportunity generator or a threat for their specific atmosphere? (2) What evidence of the affordability paradox can be found? Do the residents believe that the new train station has/may have a significant role in their cost of living? What do people think of a potential rent increase? and (3) What are the locals’ and participants’ perspectives on the current level of segregation? What do they think about integration? To what extent do the participants hope that the area will integrate into the rest of the city, both physically and socially? The study aims are to problematize and deepen the understanding of the implementation of TOD as a redevelopment strategy in low-income neighborhoods. With a critical approach, the study aims at contextualizing the contradictions of TOD and problematize the hope for newly TOD as self-evident within physical planning.

3. The Plan

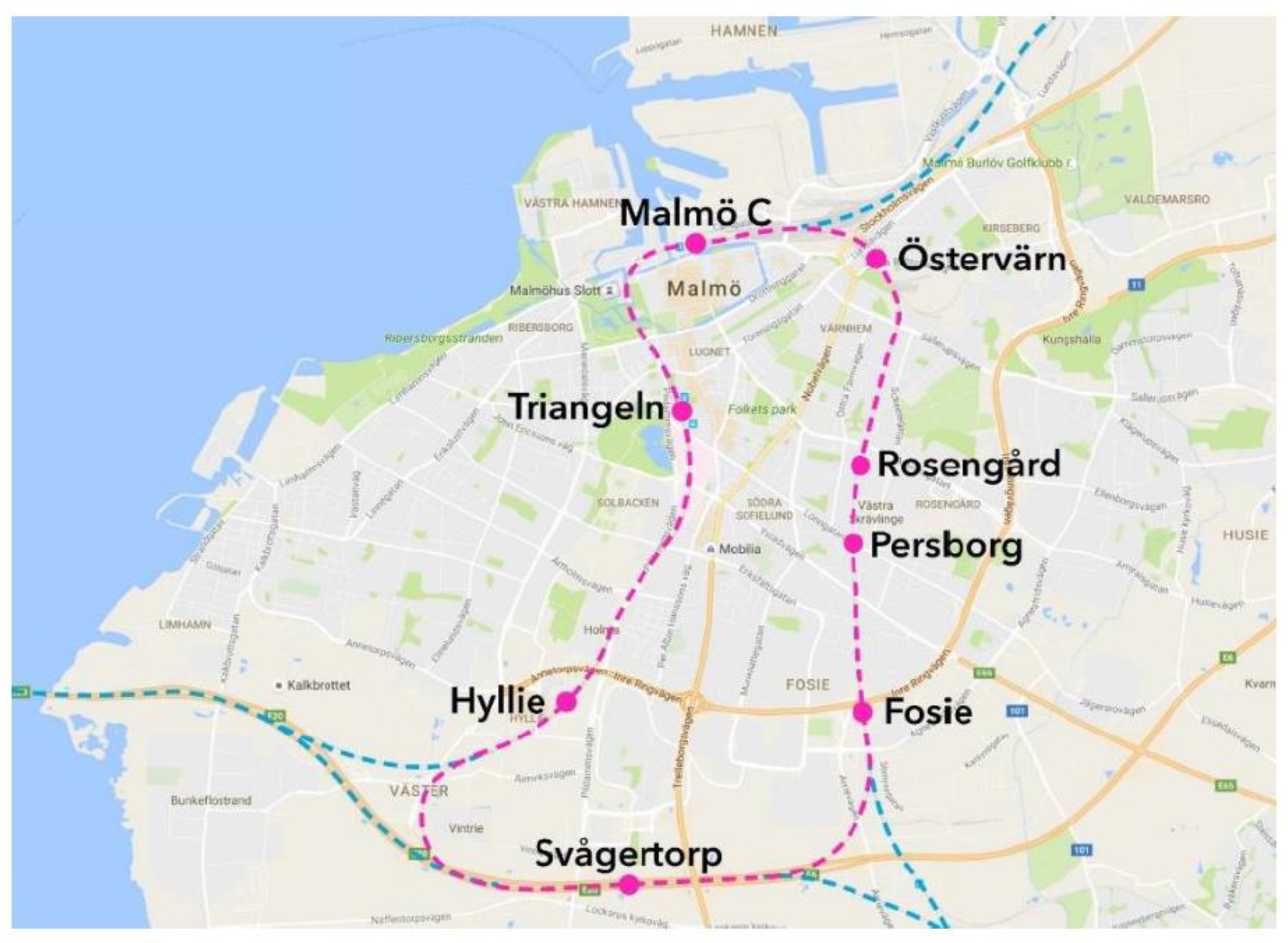

The project in which the city has waited for more than twenty years concludes a new train station and many significant transit-led investments called Culture Casbah. Culture Casbah includes a 22-story tower, 200 new homes, and 30 commercial and communal units, which are supposed to be built in a mix of new construction and redevelopment close to the new station. Furthermore, over the longer term, the developer company is planning to build a further 300 residential apartments. Rosengård’s train station was built on the continental line of Malmö. This new rail line links the somewhat deprived districts of Östervärn, Rosengård, and Persborg to Malmö Central Station in one direction and to the out-of-town shopping areas of Svågertorp and Hyllie in the other (see

Figure 1). Malmö plans to use the reopened station of Östervärn as the center of a new residential area, with up to 5000 houses and seven new schools. The station at Rosengård, meanwhile, will form the center of Admiralsstaden, with new buildings planned to fill in spaces between the Törnrosen apartment blocks and perhaps even a high-rise apartment building called Culture Casbah [

39].

Culture Casbah was approved by Malmö City Council in late 2016. To finance the project, municipal housing company MKB sold 1660 public apartments within less than 600 meters radius from the new train station to Rosengård Fastigheter, the newly formed private housing company. The company, which in fact was formed in 2017, is a joint company based on an equal cooperation of MKB Fastighets AB with three private housing companies, Fastighets AB Balder, Heimstaden, and Victoria Park AB [

39]. This new company is part of the realization of Culture Casbah. Since 2018, the company started to assess the needs to improve the area and plan the neighborhood [

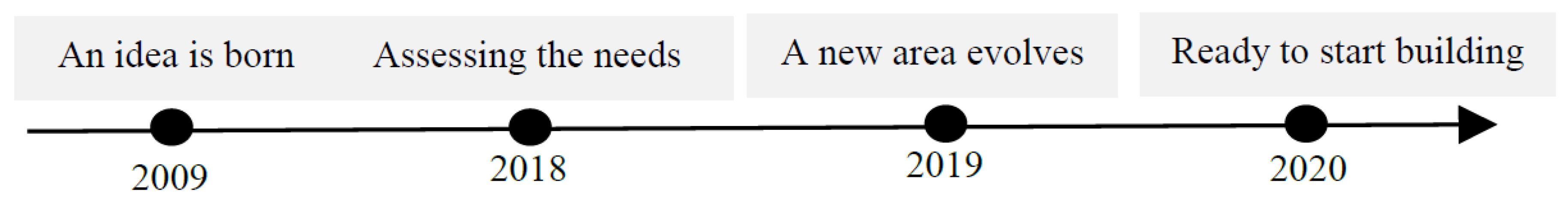

1]. The new train station was established in December 2018, and currently, the company is working on preparing a land-use plan for the neighborhood. As

Figure 2 shows, the company plans to start building the project from 2020.

Basically, the project is a part of a more important strategy for city development. According to Malmö municipality, “it’s a mobility project, it’s a social project and it’s also part of a bigger strategy”. Their idea is to combine this ring with other investments in cultural buildings and welfare buildings, so you will have a destination close to the railway station [

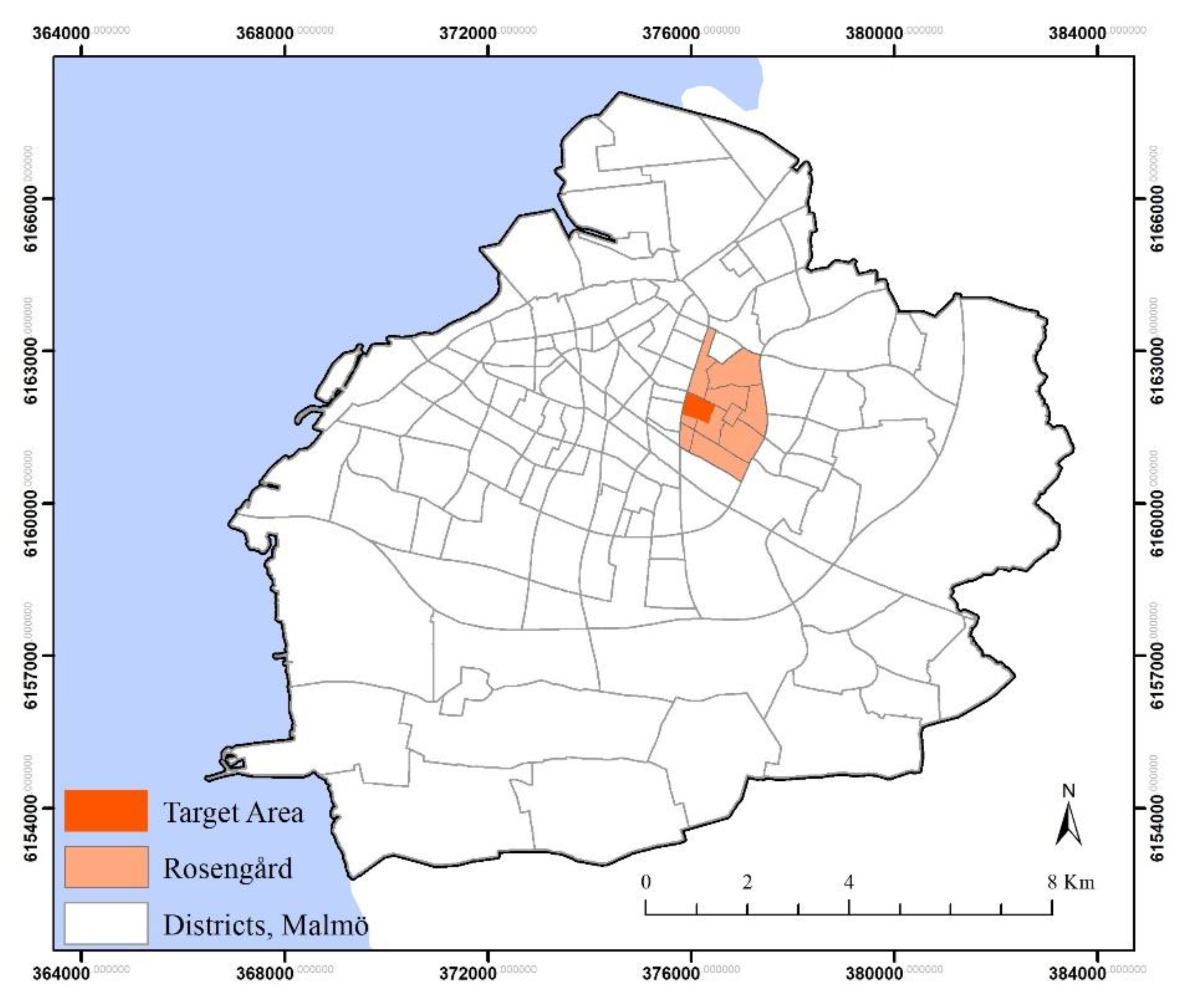

39]. Geographically, the target area includes Törnrosen and half Örtagarden, two subareas of Rosengård (see

Figure 3), with 5069 (mostly) low-income residents who live in the 1660 apartments that recently changed over to the private system (see

Figure 4).

The aim of the project is to transform Rosengård into a revitalized and dynamic urban neighborhood is rooted in the desire to activate the district’s social potential through the concentration and integration of new building forms, urban rooms, and landscapes into the existing monolithic urban structure [

1]. The tower is supposed to be a signal building that connects with neighboring areas and should be publicly accessible from base to top through a vertical “street” and also include a “social staircase” and other publicly open spaces. The tower will contain a mix of homes, offices, commerce, and cultural activities. However, in contrast to Malmö city council, the developer, and TOD planners’ hope that the project will revitalize the area and break segregation, there are many local politicians and equity advocates who have challenged the project. In the next section, I will analyze this debate broadly using some evidence from the area in order to discuss to what extent the critics’ concerns are real and policy makers’ hope are fragile.

4. Methodology

The main focus and overall emphasis in this article is inspired by critical urban theory, which involves a rejection of instrumental approaches of social scientific knowledge [

41]. The inspiration helps this research to be conducted in the way that TODs are not just accepted as an effective policy. The project is still under the detailed planning and thus, the implementation process of Culture Casbah and renovation of the apartments has not started yet. This study will discuss the policy advocate’s hope and the critic’s concern within three mentioned debates.

The research has been based on a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods. Official municipal documents, people who are living in the area, as well as other related actors (see

Table 1) were three types of selection in this case study. Statistical-demographic data, documents of the project, institutional planning documents from Malmö municipality, as well as media contents are used to provide an understanding of the project and neighborhood redevelopment strategy.

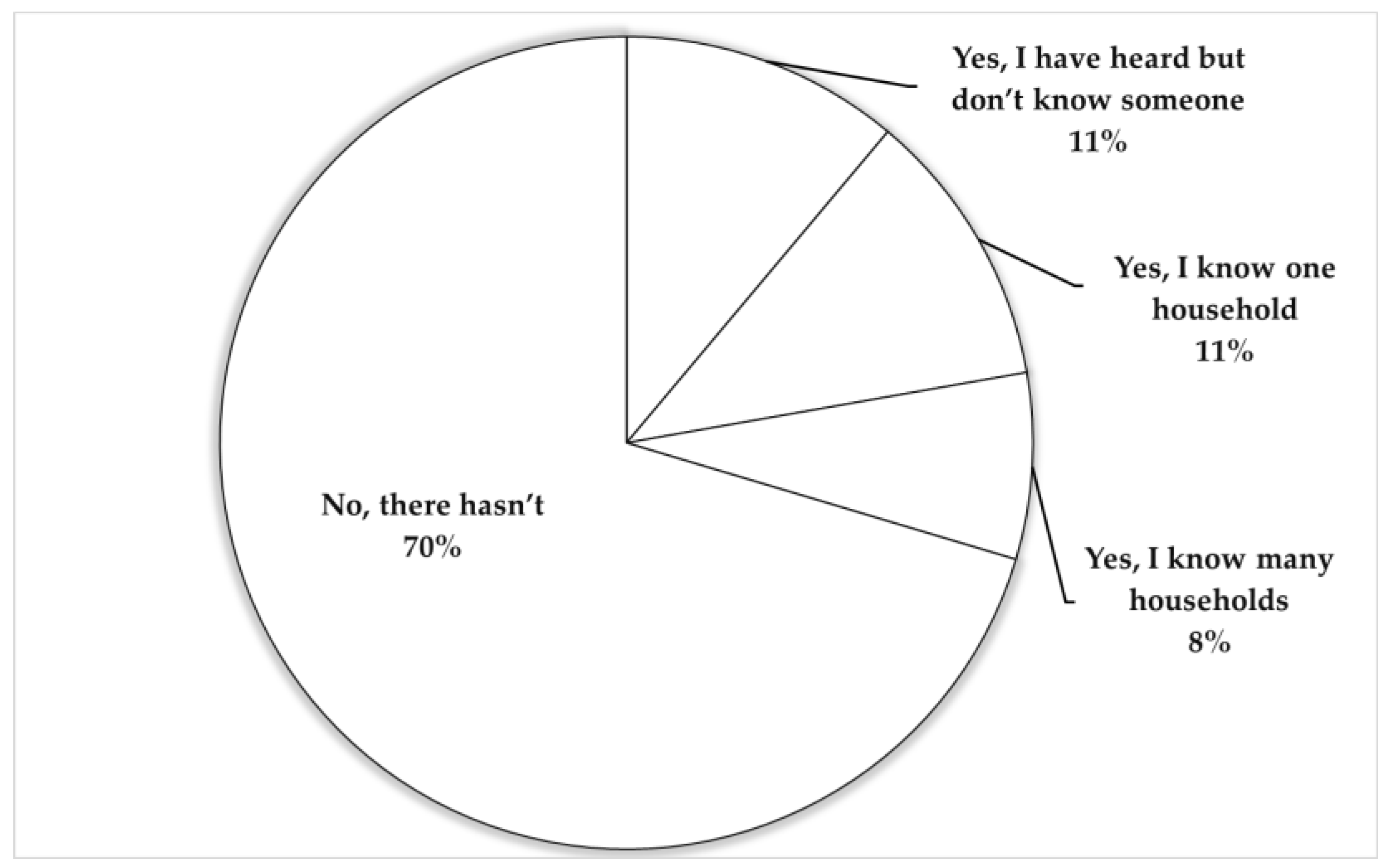

To do the quantitative survey, a questionnaire was prepared in English, Swedish, and Arabic. The target population is 5069 people and 1542 housholds [

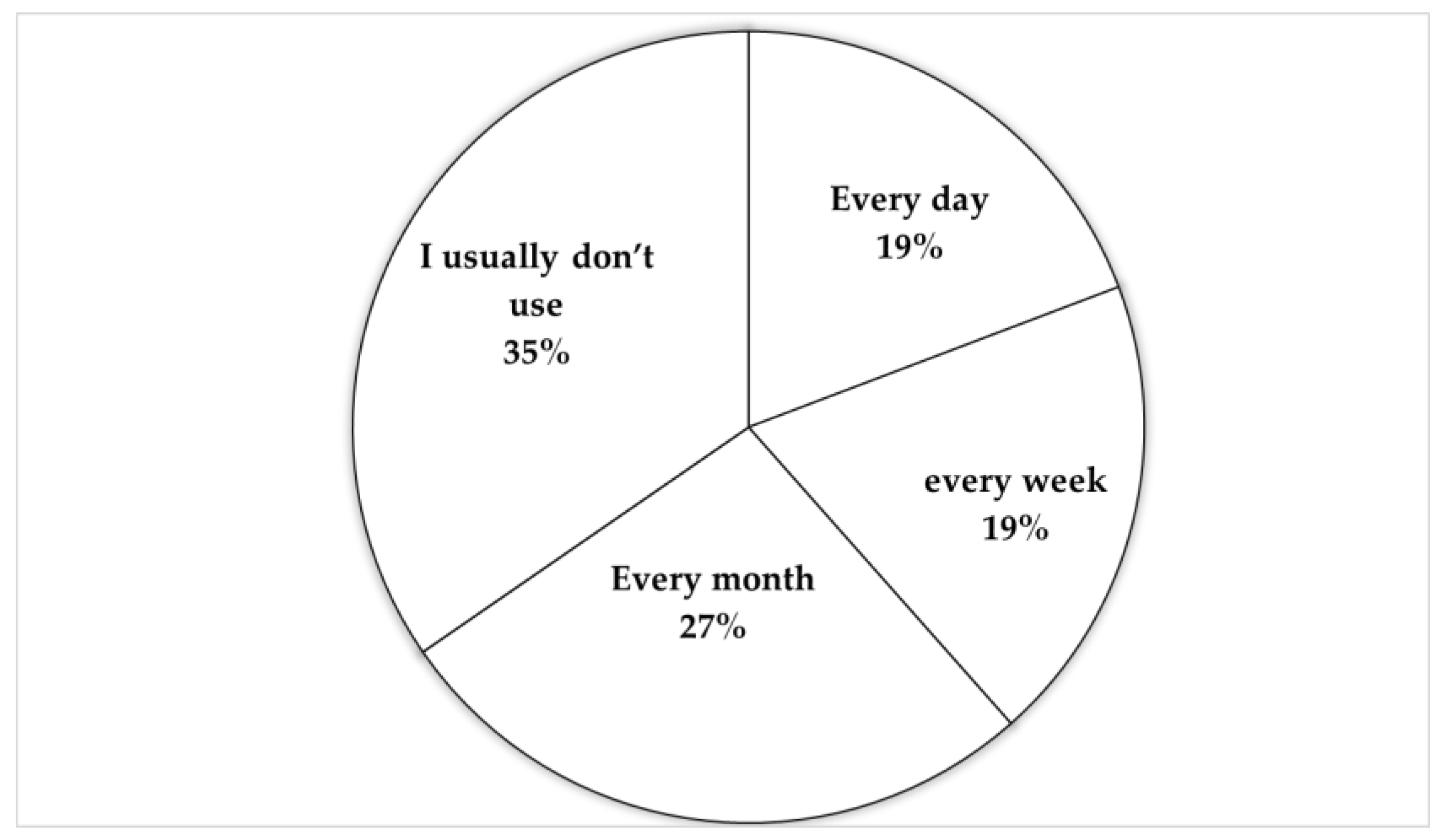

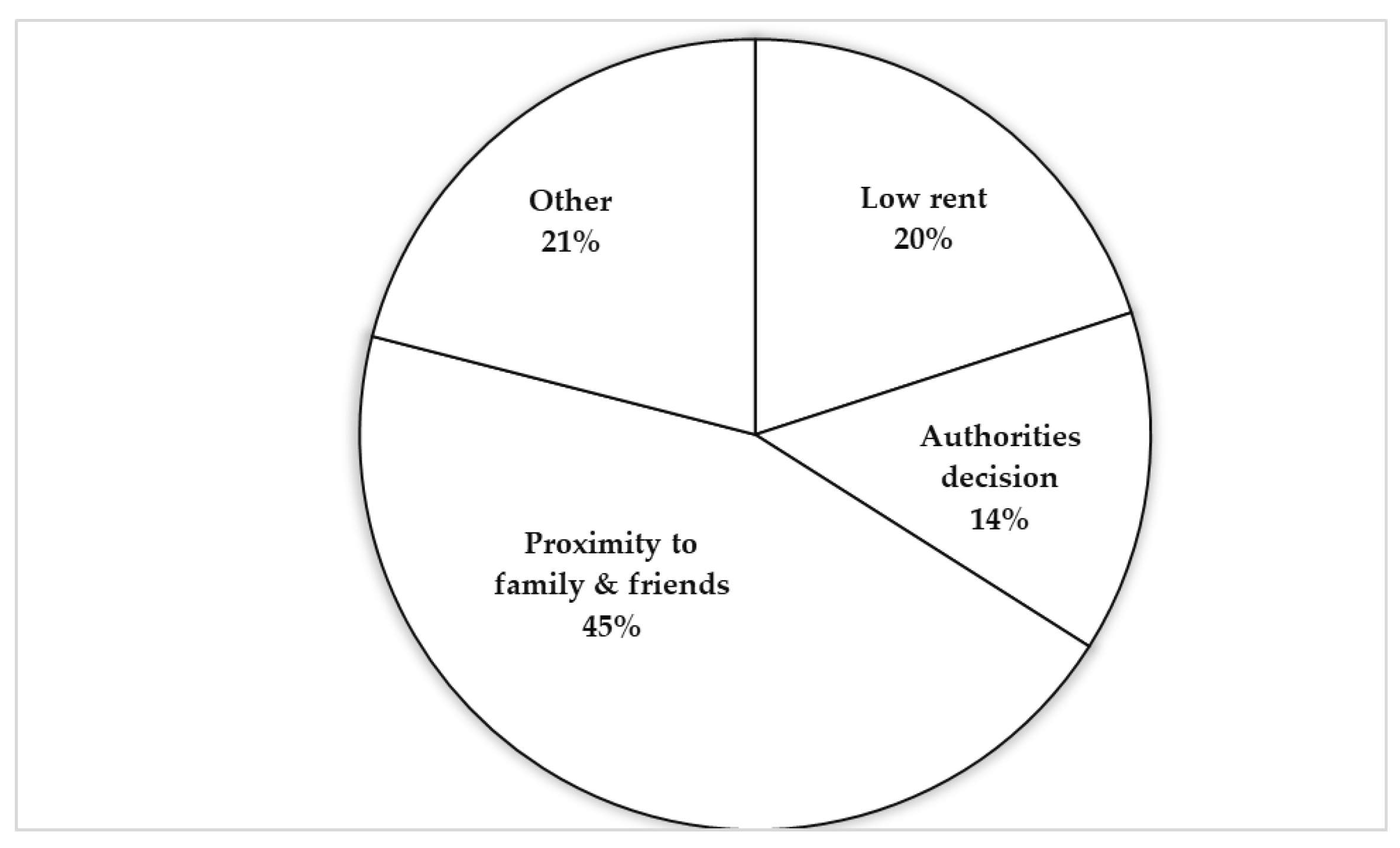

42]. The sample size (108 households) was estimated based on Cochran’s formula. Among various forms of questionnaire surveys, a paper survey as well as an online questionnaire were conducted. The questionnaire was divided into four sections. The first section focused on the size and structure of the household, their occupational and income status, the year when they moved into the current apartment, their previous place of living, as well as about the reasons and counter-reasons that influenced them to move to Rosengård or to continue to live there (Demographic questions 1–6). The next set of questions asked for information concerning the possible rent increase and household’s possible move-out/displacement (multiple choice questions 7 and 8). Questions 9–12 were about their trip pattern regarding the new train station, the use pattern of the new train station, new possible housing applications, and the possible benefits of the train for respondents. The final section (Likert scale questions 13–16) have focused on their attitudes about Culture Casbah, economic opportunities and economic resources, the current rent level, their concern regarding possible rent increase, and their perspective of Rosengård in coming years.

To find suitable respondents, authors to stayed and walked between Törnrosen and Örtagården buildings every day to find respondents who were currently living in the target area. Moreover, local mosques, Bennet’s Bazar, the Centrum, as well as the new train station were the main places where authors conducted the questionnaire survey. To achieve a rather high return rate of the questionnaires and thus a reasonably representative result, every respondent was asked beforehand whether he or she was willing to take part in the survey. For each respondent, there was a short description of the research; then, they filled out the questionnaire. Most of the time, respondents needed more explanation for some questions. Out of a hundred printed questionnaires, the authors could find 41 fully answered. Due to residents’ low-connection with smartphones and social media, the online questionnaire was not successful. Women were in a worse condition in this regard. Excepting young people, most residents did not have connection to the internet; they mostly had no email address or Facebook or telegram accounts. The survey was conducted during May 2019.

Qualitative interviews were done with four groups (

Table 1). There was a semi-structured interview conducted in the target area with 22 local residents overall (including two groups and nine residents). Interviews with local groups were conducted in two different areas; the first interview conducted in Bennet’s Bazzar with around 8 participants and the other took place in a local prayer room in Tornrosen district with 5 local participants. Interviews were conducted in English, Farsi, Turkish, and Kurdish. Each interview took 30 minutes on average. The next target group was city professionals and four interviewees selected based on their field of work and professional experience relating to Rosengård. We also had an interview with three respondents who work in physical planning within Malmö municipality in different positions and have worked on the Rosengård TOD plan. The conversations revolved around their concern about some determining factors of the Rosengård redevelopment process, new private owners, gentrification, possible displacement, affordable housing, and segregation.

In addition to interviews, the research made some findings through unsystematic observation. Observing alighting and boarding onto the train was done on two working days as well as a weekand. The aim was to observe the usage pattern of residents of the new train station. The neighborhood is a low-mobile district due to high unemployed tenants, and historically the area’s daily movement has been based on cycling and bus. Establishing the new station has been a new, cheaper and faster accessibility choice but still has not been a predominant mode of transportation in the region. The maximum number of persons boarding in each working day was less than 50 passengers, much more than total boarding at weekends. The second aim of the observation was to know about the mobility of residence specifically their connection with other parts of the city. Therefore, during long hours of unsystematic observation between buildings of Törnrosen and Örtagården and participating in religious events, it was declared that there are many prayers who do not live in Rosengård. During the interviews, it was also declared that residents of Rosengård used to go to mosques in other parts of the city. Furthermore, the observation helped authors to know that there are many customers who come to the area from small towns around Malmö such as Landskrona as well as other parts of Malmö to shop in Rosengård and visit their friends and relatives.

6. Discussion

Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) is a compact, mixed-use development within an easy walk of a transit station. Today, TOD has become a predominant model of urban planning [

6] based on the idea that there will be both social and economic benefits of implementation, e.g., reduction of CO2 emissions and urban poverty [

7], slow growth in vehicle emissions, revitalize declining urban areas, improve quality of life, and serve equity goals by increasing accessibility for the transit-dependent [

6]. However, whereas public transit is often seen as benefiting low-income and minority populations, in many cities the threat of displacement has motivated equity advocates to challenge TOD and transit investment initiatives. In many cases, advocacy groups have criticized TOD plans for exacerbating housing affordability problems and potentially displacing residents [

6]. Indeed, because people value accessibility, transit investments can increase housing prices in surrounding neighborhoods, potentially causing gentrification [

12] a phenomenon which Dawkins and Moeckel [

7] call Transit-Induced Gentrification.

These worldwide current debates on Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) were a departure point of this study. This research has tried to illustrate how the TOD plan in Rosengård district enhance the current duality of urban development in both local and national scale. As Holgersen and Baeten [

45] claimed, the development of Malmö over the past twenty years or so has been highly contradictory. On the one hand, the city has gained an international reputation for environmentally friendly planning, cutting-edge architecture, and high-end living in the Western Harbour waterfront development, and on the other hand, it is infamous for its high levels of poverty, with riots and violence often dominating the media coverage of the city [

45]. While local policy makers claim that Rosengårds’ TOD will revitalize the area, reduce poverty, and make Malmö more equal and integrated, there are many residents, city professionals, scholars, and activists who have challenged the plan regarding the risk of gentrification, displacement of low-income tenants, and more polarization and marginalization. Furthermore, as mentioned, Rosengård was established as a symbol of welfare system and currently is one of the biggest residential districts with a public housing system. Implementation of TOD strategy for such fully subsidized area is itself a controversial component. In this context, this research adapted current debates at international level to the Malmö scale and developed the apparent disagreements relating to Rosengård’s TOD and criticized the plan by discussing three mentioned debates.

Regarding the evidence/signal of the gentrification process in the district, the results indicate that the area has gradually entered into a transit-induced gentrification process; a historical background review declared that the area was built as a part of the ‘Million Home’ program in the 1960s and 1970s, then it has been a disinvestment neighborhood for many decades and the recent big reinvestment project Culture Casbah represents the third stage of the long process of capital flow. According to the literature, gentrification is the third stage of capital flow [

18]. Furthermore, the area has recently experienced a transformation from the public housing area to a market-led housing system, indicating a kind of ‘housing commodification,’ as what Madden and Marcuse [

46]) claim.Moreover, the spectacular high-rise building (Culture Casbah) with unique architecture in this disadvantaged are aims at more place branding, improving the rent gap, and facilitating the gentrification through a ‘starchitecture’ strategy. By referring to Justin McGuirk’s book, [

18] and Cocotas [

47], we can argue that this type of architecture is usually more for elites than improving ordinary people’s lives.

How these changes can be interpreted; as an urban revitalizing project and redevelopment process of a disadvantaged neighborhood or a kind of dispossession the space for profit? As discussed before, the mentioned gentrification process does not just happen on its own. According to Stein [

18], it requires investors, developers, and landlords, the “producers” of gentrification, to buy and sell land and buildings at ever-higher costs. It also requires wealthier homebuyers, renters and shoppers—the “consumers” of gentrification—to valorize areas they would have previously ignored. Planners in this process work to ensure that both sides of the relationship are present by luring gentrification’s producers with land use and tax incentives. The state in the current TOD has a central actor, marshaling investment, and chasing away threats to profits [

18]. As it is seen, the poor residents have no specific place in such urban redevelopment strategy. It is evident that the process that is currently run by TOD advocates in the area may be interpreted as a process of facilitating the gentrification than a redevelopment work to promote livability, growth, and sustainability.

In this emerging gentrifying district, the concern of displacement is real, and it has unfolded through this research in a broad meaning. Following the establishment of the new train station, one of the next main steps to realization of TOD is renovation the existing apartments. Törnrosen is the only district in Rosengård that has witnessed a reduction in population in some years since 2010. The results showed that even without renovation, there are households that moved out of the area in order to live in a lower cost house and more secure area. While some people (20%) are favorable to the new building as they may bring in some new services and make the area more attractive, others sense that the changes are aiming at attracting others than the ones living there. While for nearly half of tenants paying the existing rent level is hard, most respondents indicated that they certainly cannot not afford an increased rent level; the question arises “What will be the fate of this people?” Of course, there has been no convincing response from policymakers or the new landlord to this question.

To discuss the concern of displacement in the target area, it is evident that in this gentrifying district, the concern of displacement is real. As of today, the renovation process has not started so far, and thus, there has not been actual displacement due to the significant rent increase; however, there is some evidence of displacement pressure in the target area; tenants’ quality of life has declined due to cutting off care services. According to the local respondents, unlike previous years, tenants have to wait for weeks in order to get a response for every request to the new housing company. This situation has caused fear and anxiety in people. Cutting off necessities along with growing criminality are making the neighborhood harder to live in than ever. The survey has also shown that for nearly half of tenants paying the current rent level is hard, and most respondents indicated that they certainly could not afford an increased rent level. According to Marcuse [

19], there will be a “direct last-resident displacement” when a landlord attempts to force the renter to move by cutting off necessities or dramatically increase the rent [

21].

The next explanation is the affordability paradox of TOD in low-income neighborhoods. While it is argued that TOD improves low-income residents’ economy and helps them make their disposable income more because of reduced transportation costs, the result of this research shows that due to the high unemployment rate and little daily trips, transportation costs have no significant place in reducing the local households’ living costs. Furthermore, it is said that transit systems provide users with a ladder to economic opportunity, connecting individuals to home, work, education, healthcare, and myriad destinations. However, this ladder is most critical to low-income, transit-reliant households with little means to afford auto-oriented lifestyles [

48]. Similarly, Rojas [

49] claims that attracting a new major employer to a community is a great opportunity, but low-income residents’ access to that employer’s or other jobs requires more work. In many gentrifying areas, incumbent residents experience meaningful job losses within their home census tract, even while jobs overall increase [

50]. Regarding our case there is an enormous gap between the requirements of the potential job with the level of resident’s skills and their education status. This situation helps us to conclude that the planned TOD has no specific role in cost reduction in Rosengård, and it seems there would not be a significant improvement in low-income resident’s economy.

This kind of housing commodification in such projects has always led to a vast political struggle. “There is a conflict between housing as lived, social space and housing as an instrument for profit-making” [

46]. While the project was approved through the cooperation of Social Democrats and right-wing parties, the left parties were against the project due to their concern about rising rent level. According to M1, housing should be seen as a fundamental part of welfare, such as healthcare and education. David Harvey traces our changing relationship to housing through the city of use-value, the city of exchange value, and the city of speculative gain. He underlines that “use value” should be prioritized. As discussed above, TOD is a redevelopment profit-driven strategy which speeds up the transformation of my case from the “city of use-value” to a city of “speculative gain”. It seems that this way of urban development is ripping communities’ apart, reinforcing socio-economic segregation. Does the Swedish “circumscribed neo-liberalism” system [

51] remain a chance for those very low-income residents to have an option to maintain their current level of living? Can democratic associations like the Swedish Union of Tenants take an effective step through negotiation in this regard or their hands are tied back due to the neoliberal condition of the economy today. Moreover, it will remain unanswered whether “The Shift”, a global initiative on the right to housing, which was signed by the City of Malmö, will make sure that Rosengård’s low-income residents will benefit from the welfare values without experiencing displacement.

“New tall house symbolizes the will to unite Malmö”; this is the basic approach by MKB in the design and implementation of the Culture Casbah. To what extent may the Tower be able to unite people too? Segregation is reinforced in the field through both external and internal factors. Media, an external force, based on some evidence, is vigorously strengthening ‘Avoid Rosengård’ day by day. On the other hand, ‘poverty cycle’ and ‘cultural norms’ has led the community to make a kind of self-supportive system with specific beneficiaries for residents. Islamic cultural places function as an integrating place and have built an interconnected cultural network, has helped locals quite distinguish themselves from the others and shape a high privacy atmosphere for most local residents who prefer to maintain this paradise through their self-segregated behaviors. This study shows that the local residents may not bargain on these achievements as the TOD, of course, has not a secure alternative for them. The fact that this community has identified its specific own way to continue to live and mixing income will tear up this system leading in two possible ways; resisting or abandonment.

Moreover, the results illustrate the inability of TOD as physical planning to mitigate the current socio-economic segregation in Rosengård, as the TOD plan does not meet the residents’ need. One of the well-known aspects of segregation in Rosengård is spatial segregation. As the research showed Malmö is a rather dense city, and the area is quite close to the city center. Moreover, by the establishment of the new train station, then the area has recently linked to Central Station in one direction and the Öresund bridge through Svågertorp and Hyllie in the other. Therefore, even at the moment, Rosengård has physically well connected to the other parts of the city. The study concludes the participants’ concern of that physical integration does not fit to Rosengård’s segregationally issues and the city should pay a special attention to the current socio-economic segregation. Segregation is reinforced in the field through both external and internal factors; Media, an external force, based on some evidence, is vigorously strengthening ‘Avoid Rosengård’ day by day. On the other hand, the ‘poverty cycle’ and ‘cultural norms’ have led the community to make a kind of self-supportive system with particular beneficiaries for residents. Their interest in concentration, in fact, comes from the language barrier, lifestyle, and cultural preferences that have shaped a desired social atmosphere distinguished from the rest of the city. For most respondents, the social and cultural atmosphere is more important than the level of economic status. In other words, they prefer to live next to each other in a low-quality neighborhood than to live in a high-level neighborhood lonely. It is evident that there are two different perceptions of the current segregation; on the one hand, there are thousands of residents who have shaped their way of living and a kind of self-segregated system, and on the other hand, a transit-oriented strategy which aims at integrating this area with others; a disproportionate policy.

7. Conclusions

The purpose of this research was to discuss and deepen the understanding of the contradictions of transit-oriented development in low-income urban neighborhoods. The case study of Rosengård district was used to discuss three contradictions: transit-induced gentrification-displacement, the affordability paradox of TOD, and the segregation-integration debate. Through a mixed qualitative-quantitative method, the research aimed to develop a critical discussion about this type of urban redevelopment planning based on the residents’ perceptions and other actors’ opinions relating to the recently started TOD in Rosengård.

The study illustrated that the area has gradually entered into a transit-induced gentrification process; this process has started by privatisation of 1660 public housing and a detailed land-use to build new houses in the districts’ vacant land to concentrate the area. Furthermore, according to the plan, the renovation process will start soon and the rent for both commercial and residential properties is determined through the market system. Accordingly, the living cost in district will rise and most current low-income tenants will not be able to afford to stay in their home. In other words, they will be pushed-out and have to choose a cheaper district to live.

The study has also shown some evidence of the affordability paradox of TOD in the target area. The results indicate that the new train station has had not a significant decisive role in the resident’s income and hence it has not a significant impact on mobility costs due to the residents’ low-mobility and low ridership and the enormous gap between the requirements of the potential job with the level of resident’s skills and their education status. Therefore, it is evident that the resident’s disposable income may not experience a significant improvement.

Finally, the results challenge the ability of TOD as physical planning in mitigating the current socio-economic segregation in Rosengård. One of the well-known aspects of segregation in Rosengård is spatial segregation. As the research showed Malmö is a rather dense city, and the area is quite close to the city center. The study concludes the participants’ concern of that physical integration does not fit with Rosengård’s segregationally issues, and the city should pay a special attention to the current socio-economic segregation. It is evident that there are two different perceptions of the current segregation; on the one hand, there are thousands of residents who have shaped their way of living and a kind of self-segregated system, and on the other hand, a transit-oriented strategy which aims at integrating this area with others; a disproportionate policy.

8. Limitations and Further Research

The results of discussion in this research indicate that there is no conclusive orientation to whether running TOD projects in low-income neighborhoods leads to actual displacement and more marginalization or not. Based on a critical approach within the context of neoliberal urbanism this study aimed to open up to a dialogue on contradictory achievements of the current way of redevelopment processes in disadvantaged neghborhoods in Malmö.

Next studies can be conducted with less limitations than this paper has faced. Dealing with people in different cultures and different languages in the area, which in many cases created a barrier to having an active interaction was the first limitation. Moreover, finding the right respondent (living in the target area, being able to write his/her opinion and being conscious of new changes in the area) and interested in answering the questions responsively was challenging and needs much more time to survey. The next limitation is related to those people who could speak Swedish or their original language but could not write their own ideas on the paper. Furthermore, to develop the discussion, active politicians’ participation is crucial. In this research, authors were interested in getting policymakers and politicians’ opinions directly through an interview, but due to some reasons (the European election 2019, the specificity of the case, unwillingness to participate in the research), it did not happen.

This work has been done at the time of the first phase of the TOD project of Rosengård, and it is too soon to judge the project in practice; hence, rigid studies and more scientific evidence are needed to trace the reality of this duality in this neighborhood. Finally, discussing the contradictions of TOD in low-income neighborhoods in Sweden revealed that this form of urban redevelopment maybe a way of re-using the space for more profit and a strategy for reproduction the space by the capital, which basically is in contrast to the goals of TOD, the right to housing as well as the goast of the Swedish welfare system. More profound research is needed to respond to two categories of unknowns; rigid research is needed to measure changes in Rosengård in the next few years and evaluate to what extent the current concerns may be realized, how will the area experience gentrification and displacement, and what factors may enhance or slowdown this process. Comparative studies are also needed to investigate the similarities between the cautionary neoliberalism experience in Swedish urbanization and the other western experiences of transit-induced gentrification, housing commodification, and displacement.