Abstract

Participatory action combined interventionist research approaches can offer possibilities for community-based facilities and institutions attempting to re-engage with their communities and assert their presence. St. Cuthbert’s Church is a heritage-listed property, located on a major landholding, right in the heart of the summer tourist town of Lorne, on Melbourne’s peri-urban ‘sea change’ fringe. Its sloping hillside vantage offers spectacular views to the beach and Bass Strait, beyond. The congregation, however, is aging, while the broader community is increasingly secular. In response to these circumstances, the Church is looking to assert its relevance with the procurement of a community centre to be erected on the property. Using an interventionist research approach, with a professional facilitator in ‘participatory action design’, it was found that while both residents and visitors to Lorne were favourably disposed to the idea of a community centre, it was also clear that the locus of power that needed to realise this objective lay outside the congregation’s control. A conclusion of this research is that community-based organisations may have to pro-actively engage in professional marketing and prepare business plans, as well as engage in substantial political lobbying both within and external to the Church, if the project is to progress and succeed.

- “Buy my hot wood clematis,

- Buy a frond of fern

- Gathered where the Erskine leaps

- Down the road to Lorne,

- Buy my Christmas creeper

- And I’ll say where you were born.”

Rudyard Kipling–quoted in Wood [1].

1. Introduction

The Lorne Uniting Church is the largest non-governmental provider of community services in Australia. It is represented in over 400 agencies. The Uniting Care network alone, the social infrastructure services arm within the Church, has over 1400 physical sites, 40,000 employees and is supported by 30,000 volunteers [1]. In the spirit of this tradition of community mission work, the Lorne Uniting Church proposed to develop a community centre on its extensive, centrally located property on Mountjoy Parade, Lorne, which both overlooks Bass Strait as well as Lorne’s main street.

The project, however, was not without major challenges. These included an aging and diminishing local church congregation, difficulties in identifying viable uses for the community centre, as well as significant financial constraints. These obstacles sit within a larger trend taking place within Australia of steadily increasing secularization.

This paper documents the journey being taken by the Lorne Uniting Church as it seeks to realise its goal of establishing a community centre. It begins with the historical background of Lorne and the Church. It outlines the participation of Deakin University (Deakin) in facilitating stakeholder engagement of both the congregation and the community, through participatory action engagement and interventionist strategies, and offers a summary of research conducted surveying community expectations. It closes with reflections on the road travelled thus far, and the road ahead.

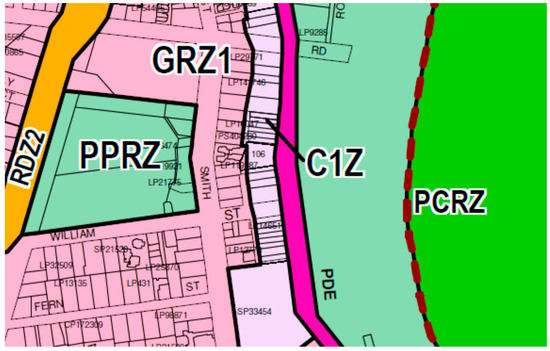

The subject land is covered by the Surf Coast Planning Scheme (2019 vers.) [2], a statutory legal planning instrument established under the Victorian state Planning & Environment Act 1987 [3]. The upperhill 50% portion of the subject land is zoned General Residential Zone 1 (GRZ1 on Figure 1.) (Clause 32.08) of which a ‘Place of Worship’ is a Section 1 permissible use, and a ‘Place of Assembly’ is a Section 2 conditional use. The downhill 50% portion of the subject land is zoned Commercial 1 Zone (C1Z on Figure 1) (Clause 34.01), of which a ‘Place of Worship’ is a Section 1 permissible use and a ‘Place of Assembly’ is a Section 2 conditional use.

Figure 1.

Extract of the Surf Coast Planning Scheme (Victoria, 2019: Map 43zn) for the subject land. Source: Surf Coast Planning Scheme (Victoria, 2019 vers.) [2]. Commons licence.

2. Research Approach

The participatory action and interventionist methodologies employed sought to establish a process by which the Lorne Uniting Church could move towards its goal of procuring a community centre on its Mountjoy Parade property. The investigative lens borrows from social change and actor network theories. The investigation itself is methodologically interventionist, seeking to shape positively the outcome, while also documenting the journey taken.

2.1. Theoretical Lens

There are any number of theoretical perspectives available to facilitate understanding of the stakeholder dynamics shaping the outcome of the project under investigation. Each offers its own contributions and limitations.

At the macro level are social change theories. These theories attempt to explain social change through evolutionary, functionalist or conflictual paradigms; where change comes about through far-reaching external forces [4,5]. Thus, arguably, the barriers faced in realizing a community centre can be understood as unfolding within the broader existential threats confronting Christianity in Australia generally. Where once Australians (with the exception of the animist beliefs of its Indigenous populations) almost wholly identified as Christian, the Australian 2016 census reported that only 52% identified as having any Christian affiliation. This is a 40% drop in just 30 years; with 73% of Australians classifying themselves as Christian only a generation earlier, in 1986. Over that same period, Uniting Church membership has sunk from 1.18 million to just 0.87 million [6,7]. Two years on, in 2018, the Uniting Church claimed a paltry 243,000 members [8]. According to a Gallup Poll, Australia is now ranked the 12th most secular country in the world (out of 196), with only 34% expressing any religious conviction. Moreover, the longer-term projection is for a continued decline of this statistic [9].

The growing secularization of Western societies explains further trends. On the one hand, shrinking church membership accounts, at least partly, for the consolidation of denominations–much as corporations with reducing market share become targets for take-overs. The Uniting Church Australia was established 22 June 1977, with the amalgamation of about two-thirds of the Presbyterian Church (of which St. Cuthbert’s was affiliated), the Methodist Church of Australasia, and the Congregational Church [10]. The ‘uniting’ elevated the church to third in size behind the Catholic and Anglican churches [11].

Similarly, while the Uniting Church is the largest non-government provider of community services in Australia, with over 400 agencies offering health care, aged care, drug and alcohol rehabilitation, homelessness and emergency services, etc., its social services footprint is diminishing. Over the period 2014 to 2016, the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC) revoked the charity status of 11,698 charities, leaving 2600 less than were previously registered [12]. Here again, the overarching trajectory of social change is for social services to take on a secular flavour, being subsumed by expanding government agencies, at the expense of shrinking charitable institutions [13]. This background offers a clarifying lens through which to interpret the community centre project under consideration here.

At the level of the project itself, Actor Network Theory (ANT) offers further explanatory power. ANT is more an analytical instrument than a theory, as such. It was developed in the 1980s, primarily by Michel Callon and Bruno Latour, at the Centre de Sociologie de l’Innovation, at the Mines Paristech in Paris, as a mechanism for describing how complex projects come to fruition under conditions of great uncertainty and complexity [14]. Their argument was that projects were best understood as not abiding primarily within the control of those charged with bringing the project to pass, but rather exist within a network. While human participation in a project’s development might be transitory, they argue that it is the stability of the network within which a project is being undertaken that determines a project’s success. Bureaucracies, regulations, procedures, systems, affiliations, convictions and agreements, as much as the artefacts they produce along the way, are as important nodes within the network as the project team members themselves [15].

A key insight of ANT is that for a project to be realised, the boundless range of possibilities open to it at the outset, must steadily be reduced and channelled towards an ever-reducing set of finite alternatives [16]. In considering the St. Cuthbert’s Community Centre project from an ANT perspective, a number of observations are possible. For example, the St. Cuthbert’s Minister, who first championed the project, and who invited Deakin University’s involvement, announced her resignation from the Ministry effective January 2019. This would appear to be a significant set-back for the project. However, her legacy, with regards to the capacity of the project to find completion, rests in the degree to which she has managed to consolidate progress. This is evidenced in the agreements, commitments, approvals and similar, which effectively prevented her replacement from winding the project back or abandoning it.

Put another way, the progression of the project can be considered as a sequence of exercises in closing doors that force stakeholders to move forward along the project’s pathway.

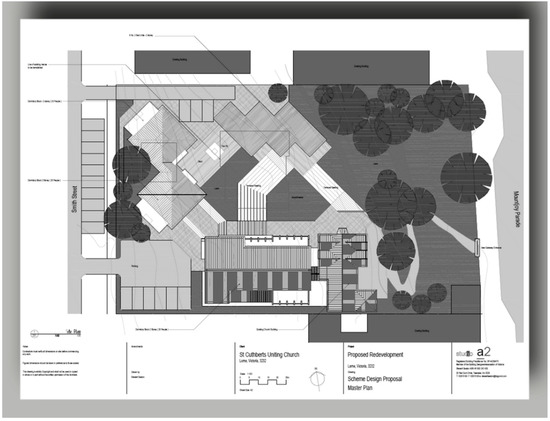

Another example would be the proposed schematic drawings produced by the architect to date. These are a physical artefact that cannot now be ignored. They articulate a set of functions to be served by the proposed Community Centre, even though the purpose of the Centre has not been formally fixed and agreed. On the one hand, it would appear that the drawings have been produced prematurely. Yet, on the other hand, their existence, such as they are, present a barrier that stands in defiance of any stakeholder’s intentions to significantly shift the project in a new alternate direction [17]. Extant models, drawings documents, and similar, have their own loud voice in the project debate. See Figure 2 and Figure 6.

Figure 2.

Architectural drawing for the proposed community center. St. Cuthbert’s Church appears at the bottom of the site, right of centre. Source: image reproduced with the consent of the director of studio a2, architect Stewart Seaton.

The overall research has followed a case study approach as described by Yin [18].

2.2. Research Method

The Lorne Uniting Church congregation, led by their Minister, aim to be of proactive relevance to their community. In a time of societal transition, determining the course to pursue in achieving that aim is unclear. Consequently, decisions about how to go about procuring a Community Centre are predicated on first establishing what needs that Centre should fulfil. This is all the more problematic since serving the cause of the Church and serving the community at large, though certainly overlapping, are not necessarily congruent. Pointedly, some congregation members perceive that ‘serving God’ and his Ministry should be prioritised over merely catering to the temporal needs of the broader community.

In documenting the process by which the Lorne Uniting Church is pursuing, Deakin University took an interventionist approach, offering the expertise of an outside, trained facilitator in ‘participatory action design.’

Interventionist research is a recognised research paradigm in which the researcher ‘is directly involved in the real-time flow of events instead of observing at a distance or working with ex post facts’ [19]. This allowed Deakin to take an insider’s view of proceedings, while at the same time providing substantive, professional assistance.

3. Background

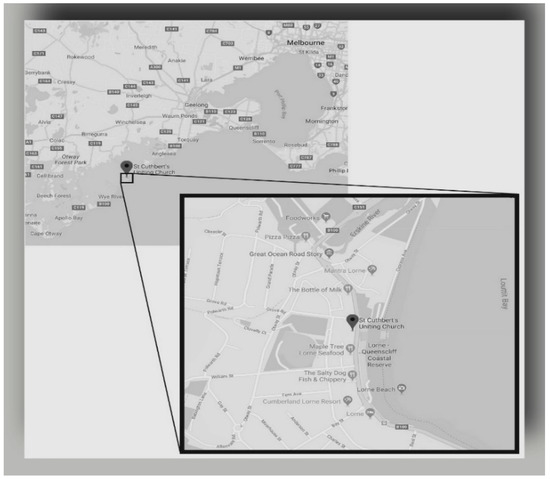

St. Cuthbert’s is a Uniting Church property situated at 86 Mountjoy Parade, Lorne, Victoria, Australia. The location is prime, sitting in the heart of the commercial centre of Lorne’s main tourist and shopping thoroughfare, with shops, cafés and restaurants either side. It is just across the road from the beach, and given the site is heavily sloped, rising towards the hill-line behind the town, offers spectacular views of the beach and the waters of Bass Strait beyond [20]. Lorne lies 65 km south-west of Geelong, midway between Geelong and Cape Otway, on the national heritage listed Great Ocean Road (see Figure 3). Lorne, in turn, is part of the Surf Coast Shire municipality, which has a population of 30,000, supporting 9000 jobs and a Gross Regional Product of AUD$1.2 billion [21]; of which one quarter of this value is derived from the surfing industry [22]. While Lorne itself only has 1100 registered residents, its economy is intricately linked to the flow of tourists and summer holiday makers that visit the Surf Coast Region. Lorne’s mid-summer holiday population can rise to more than triple its winter numbers [23].

Figure 3.

Locational map of St. Cuthbert’s, Lorne, Victoria. Source: www.google.com/maps [24]. Commons licence.

3.1. History of Lorne

Though only a small, coastal town, Lorne has a relatively long history. The earliest known inhabitants of the area were the ‘Gadubanud’ people. They traded spear wood for green stone mined by the ‘Wurundjeri’ people, who lived further inland [25]. In 1798, nautical explorers Bass and Flinders sailed through the passage between Tasmania and the Australian mainland, proving that these land masses were not physically connected. This raised interest amongst European settlers in establishing colonies along this newly discovered coastline. Pastoralist Edward Henty established Portland, to the west of present-day Lorne in 1843; one year before entrepreneur John Batman founded Melbourne. Indeed, for a time, Portland was slated to be Victoria’s capital city. Even earlier, to the east, in 1803, Lieutenant Governor David Collins established an ill-fated penal settlement near Sorrento; on the other side of Port Philip Bay [26]. In fact, the settlement’s most famous escapee, William Buckley, was the first European to visit the Lorne area. He lived with the ‘Gadubanud’ and ‘Wadawurrung’ peoples for 32 years, learning their languages. Eventually he gave himself up and was later pardoned, in 1835, for his work in liaising between the ‘Kulin Nation’ peoples and the new colonial arrivals [27].

In 1841, a heavy storm forced Captain Loutit to seek refuge for his schooner in the bay where Lorne now stands. He reported the bay’s idyllic qualities to Melbourne’s settlers. Five years later, the area was surveyed by George Smythe, and named Loutit Bay. Around this time, William Lindsay explored the region overland, searching for coal, but discovered instead the locales valuable timber. In 1849, Lindsay was granted a logger’s license. He built a home on a flank of the Erskine River that exits into Loutit Bay. Both his sons died tragically in accidents in 1850, but soon after new arrivals appeared and began farming in the locality [28]. Logging, fishing, as well as Lorne’s growing reputation for natural beauty, attracted an influx of settlers. A number of guest houses were built to cater for the visitors. By 1869, the overland traffic to Lorne had grown to the extent that a wheeled bridle track across the Otway Ranges was commissioned. This made access for more settlers possible. Consequently, that year, the budding township was renamed ‘Lorne,’ after the Marquis of Lorne, then the 9th Duke of Argyll. Thereafter, the surveyor Alexander Allan, offered 29 allotments of two acres (0.8 ha), for purchase, and in 1876 Duncan and Hancock built the majestic Lorne Hotel [29].

3.2. The St. Cuthbert’s Church Properties

As the Lorne community grew, the need for places of worship became apparent. Community members were principally divided between the Church of England and Presbyterian faiths. At a meeting held 10 November 1879, presided over by the Church of England lay reader J. T. Evans, it was agreed to begin regular church services at Erskine House; later known as the ‘Sanctuary’. In January 1880, the Bishop of Melbourne visited Lorne, donating £20 towards a church. Henry Gwynne donated £50 and a half acre of land (0.2 ha). By March construction was underway, and Lorne’s first church was consecrated in November [1,11].

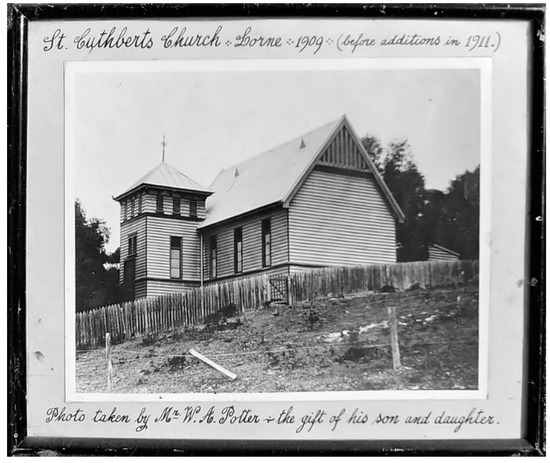

As an interim measure, the Presbyterians began offering their own services at nearby Deans Marsh, in 1890 [30]. St. Cuthbert’s Presbyterian Church followed—positioned right on the main beach road on a site with a 12.1 m frontage; 40.2 m deep [8]. The building was a gabled structure of Baltic pine, brought out as ship’s ballast from Europe; 10.6 m long by 7.6 m wide, with a 2.7 by 2.7 m porch. While the successful tender went to a J. W. Dent of Geelong, the actual builder was a Scottish cabinet-maker, Andrew Sanger. The church cost £195. It was opened on 12 January 1892, by the Reverend Arthur Davidson, with its first service delivered on Sunday 7 February 1892, presided over by the Reverend Alexander Stewart, of Essendon [16,19]. See Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Photo of St. Cuthbert’s church c.1909, prior to additions. Source: image reproduced with the permission of Sam Coulson, Treasurer, Lorne Anglican-Uniting Church, Lorne (original photo taken by W. A. Potter).

In 1907, Reverend J. McNair appointed a committee for the acquisition of further adjoining land in anticipation of future church requirements. As it turned out, James Buick had purchased most of the surrounding land in 1904. While the original allotment 3, on which St. Cuthbert’s stood, had cost £160, Buick generously offered the remaining allotments he had accumulated to the Presbyterian Church for just £164. Title transfer was executed 25 May 1908, giving the Presbyterian Church possession of a combined parcel of land that extended from Mountjoy Parade all the way up the hill to Smith Street [27,29,31].

In 1911, the pulpit area was moved to the north side of the building, and transepts were added, giving the church a cruciform plan. Sanger was again commissioned, in 1918, to add a vestry, which he did at no cost. The windows were a gift from a Mrs. J. Boyd, while the pulpit was donated by the Buick family. Numerous other contributions and gifts of appreciation today adorn the Church [25,29]. A view of St. Cuthbert’s is shown in Figure 5a. In 1975, the building was classified by the National Trust of Australia (Victoria) [31]. The classification citation reads: “A pleasing timber church with open strappings in the gables and a handsome boarded interior.”

Figure 5.

Photos of the Uniting Church’s Mountjoy Parade, Lorne, properties. (a) St. Cuthbert’s Church. (b) The Hall. Source: authors.

The second major building on the property is the Church manse. A proposal for building a manse was first recorded in the Church minutes of February 1919. The Church congregation organised numerous community and fund-raising activities; from fetes to tennis tournaments. A manse committee member, R. Dennis, designed the building, with Geelong architects Laird and Buchan sending the project to tender. A final contribution of £200 from Miss Buick made it possible to accept the tender price of £1855, and work began on the building on 23 January 1928. Further donations furnished the manse, and it was formally opened by Mrs. Sanger, 9 April 1928 [8,9,11]. In 1953, a sun room was added, enclosing the veranda [31]. A view of the manse is shown in Figure 6a.

Figure 6.

Photos of the Uniting Church’s Mountjoy Parade, Lorne, properties. (a) The Manse. Photo source: authors. (b) Model of the existing site. Photo source: authors; model image reproduced with the consent of the director of studio a2, architect Stewart Seaton.

The third major building on the church property is the Sunday School Hall. Sunday School classes were held at the home of Mrs. Sanger, in William Street, as early as 1923. But it was not until 1957 that a dedicated plan was formulated to build a purpose-built building. A site in Charles Street, that had been donated by Miss Hastie in 1891, was sold off to raise the needed funds for the hall project. Originally, the Charles Street location was intended as a sanatorium for ministers, but that proposal was abandoned. It took some years to sell off the land, but by 1960 the Church had raised the £4900 needed to realise J. Gordon Williams’ design. The Sunday School Hall was opened by the Moderator of Geelong, Reverend D.W. Matthews, on 3 September 1961. A view of the Hall is shown in Figure 5b. During the 1960s, some 35 children attended senior classes, with junior classes absorbing children from the nearby Anglican and Catholic churches. The Hall was remodelled in 1975; a stage being added, along with partition walling to separate classes [26,29].

3.3. The Current Project

In November 2017, the current Minister engaged a local architect to produce a schematic design proposal for a radical redevelopment of the site. The underlying motivation was to capitalise on St. Cuthbert’s prominent location, within the town, and to improve the Church’s connectedness, usefulness and, ultimately, relevance.

The ambitious brief for the redevelopment included:

- Refurbishment and extension of the existing (Sunday School) Hall to create a multi-functional building that would be available to groups within and beyond the Church community for events and meetings, with appropriate support facilities, and establishing a physical connection with the Church building itself;

- Demolition of the existing Manse to make way for new accommodation for groups and families;

- Extensive remodelling of the site and gardens to include an amphitheatre and outdoor performance space that would capitalise on the site’s natural inclined topography, and its outlook to Mountjoy Parade and the beach beyond;

- Provision of access and parking to the top of the site, from Smith Street.

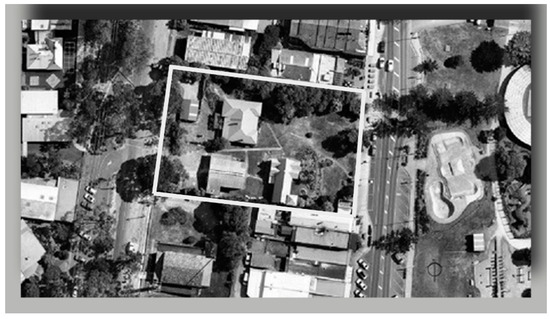

An aerial view of the site is shown in Figure 7. An initial architectural response to the brief is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 7.

Aerial view of the Lorne Uniting Church site. Source: www.nearmap.com.au [32]. Commons licence.

There are a number of technical and regulatory factors that impact the development of the site:

- The church building itself is heritage listed, and any proposed works to the Church building need to be developed in consultation with the appropriate building and planning authorities;

- The steeply inclined site presents challenges to construction methodology and costing;

- No money is currently available to fund the project.

The project was initially driven principally by the singular vision and ambition of the Church Minister along with a core group of the Church congregation. As with most grass roots projects, there is an apparent lack of funding. The project budget for the proposed redevelopment was estimated at AUD$10 million. Both the State and Federal Governments were approached for support, but no tangible commitment was forthcoming. The Uniting Church, themselves, have made no formal commitment to support the proposal, financially or otherwise. The ambition of the Uniting Church leadership in terms of the future of the site remains unstated.

Following the Wye River bushfire of December 2015, which had a devastating impact upon that community and a strong flow-on effect on neighbouring Lorne, Deakin University, along with other community organizations and institutions with ties to the Great Ocean Road corridor offered support.

In January 2017, the Lorne Uniting Church, represented by their Minister, accepted Deakin’s offer to record, document and, to some degree, facilitate the process by which the Uniting Church could move forward in its efforts to achieve its goal of revamping and revitalizing its current Church complex. The aim was and is to retain St. Cuthbert’s traditions as a mainstay pillar of the Lorne community, while also adapting and adjusting to the clearly changing demographics and circumstances of present-day Lorne that are overshadowing these early traditions.

This paper presents the journey undertaken by St. Cuthbert’s in initiating and exploring the possibilities a new community centre, situated on Uniting Church property, might offer the township of Lorne through an interventionist methodology facilitated by Deakin University.

4. Intervention Outcomes

Three key interventionist events took place during the process. These included two workshops facilitated by the outside expert in community engagement and stakeholder planning (held in June and November 2018), as well as the staging of a ‘listening post’ (held in January 2019), in which community views on the proposed Community Centre were garnered. The outcomes are reported hereunder.

4.1. Project Action Plan Workshop

On 17 June 2018, Deakin University facilitated a workshop with representatives of the Lorne Uniting Church congregation, including its Minister. 16 members of the congregation attended, most of whom were retirees with long-standing involvement with the Church. The articulated mission of the attendees was to procure ‘a fantastic facility on the site we all love.’

A list of underlying blockages hindering the procurement of a Community Centre was identified. These were:

- Undefined clarity of purpose;

- No articulated shared vision;

- Absence of a formal business plan;

- Need for broader community input and support;

- Need for plans, approvals and finance;

- Need for human resources.

An action plan was developed to address these blockages, including formalizing a project steering committee, making representations to the Surf Coast Council, and the garnering of community views and interest through a ‘listening post.’

4.2. Follow-Up Workshop

In a follow-up workshop held on 3 November 2018, parameters for the project were defined. This included identifying those variables that were and were not negotiable. The list is presented as Table 1.

Table 1.

St. Cuthbert’s Community Centre steering committee’s list of ‘Negotiable’ and ‘Not Negotiable’ project items.

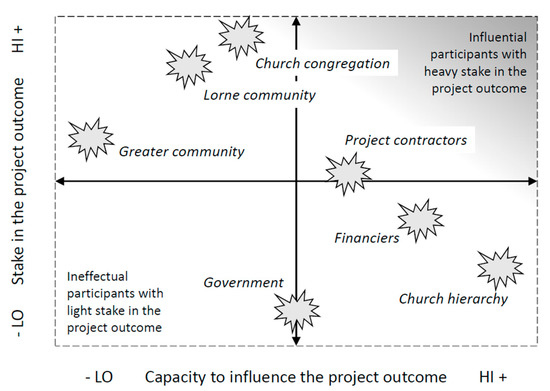

What became apparent was that there were a significant number of stakeholders interested in the project, each of whom had unequal buy-in to the idea of a Community Centre. Additionally, each held varying levels of influence on the project’s decision-making process. Seven major stakeholders were identified. These seven were first ranked in order of the degree to which the project would impact them. They were then ranked in order of their capacity to influence the project outcome. The resulting stakeholder analysis is plotted in Figure 8. What stood out in particular was that the three groups for whom the nature, purpose and design of a Community Centre would be most significant; the Church congregation, the Lorne community, and the greater community have the least power to influence the project. This is perhaps the most interesting theoretical conclusion from this research project.

Figure 8.

Degree of impact of the project on various stakeholders, plotted against their capacity to influence the project outcome.

Contrariwise, three groups with the greatest say in shaping the destiny of the project—the Church leadership, financial backers and government authorities—ultimately will only be marginally impacted by the project whose destiny they will shape. In the centre are the project contractors—the designers and builders—who have a significant influence on the project’s ultimate realization, and who have a vested interest in achieving financial and reputational gain from their involvement.

From the perspective of ANT, the insight to be drawn is that while the Uniting Church Minister and her congregation understand the project to be theirs—conceived and initiated by them—the primary locus of power necessary to drive the project forward remains outside their domain. The Lorne Church is effectively an outsider to its own project. Consequently, if the project is to gain traction, the ‘grass-roots activism’ of the congregation must find an avenue into the Church hierarchy and a lobbying mechanism by which to sway it to their ambitions.

To be clear, no stakeholder in the Community Centre project was determined to be both highly committed to the project’s fruition nor highly influential in shaping its outcome. This was flagged as a major threat to the project’s ultimate success.

4.3. ‘Listening Post’ Survey Questionnaire Results

On a warm, summer Saturday, 19 January 2019, a ‘listening post’ pavilion was set up on Lorne’s main thoroughfare, Mountjoy Parade, at the foot of St. Cuthbert’s Church. The pavilion, comprising a tent-structure located on the main street footpath, filled with the development plans and building material samples, was a response to the earlier Action Plan of June 2018. It housed an exhibition of the various proposals being considered by the Church for the Community Centre. Being peak holiday season, many people were in Lorne for the day, both from nearby, as well as from farther afield (Geelong and Melbourne), and were walking up and down the main street footpath. Passers-by were asked to fill in a questionnaire seeking opinions regarding the Community Centre. A summary of the results is reported below.

The questionnaire questions are set out in Table 2. The design of the questions was derived from the findings of the 3 November 2018 workshop, and a research team progress review. The questionnaire design was also subject to review and approval by Deakin University’s Faculty of Science Engineering & Built Environment. The latter is a normal required protocol process in Australian academia where human (from medical to perceptive to observational) research activities are about to be entertained to elucidate patterns, trends, preferences and values.

Table 2.

Listening Post Questions.

64 participants completed the questionnaires. Of these, only 20 came from locals; 44 (69%) of respondents were day visitors who lived outside Lorne. This finding supports the narrative that the Lorne community is heavily impacted, if not also greatly dependent, on the transient tourist trade. Even so, without exception, all 64 respondents supported the concept of a Lorne Community Centre—there were no dissenting views.

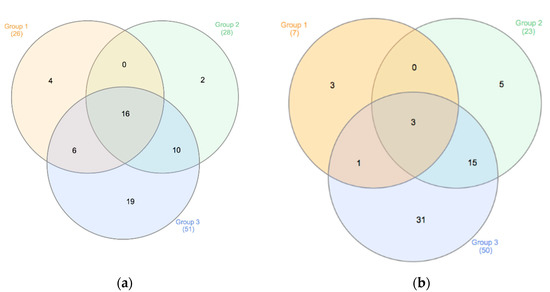

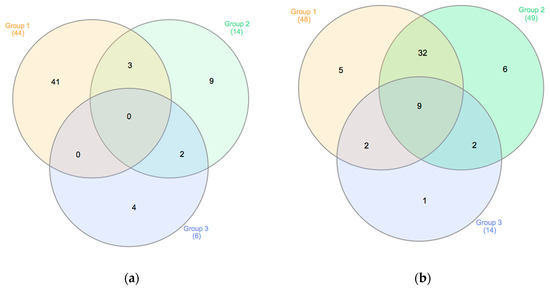

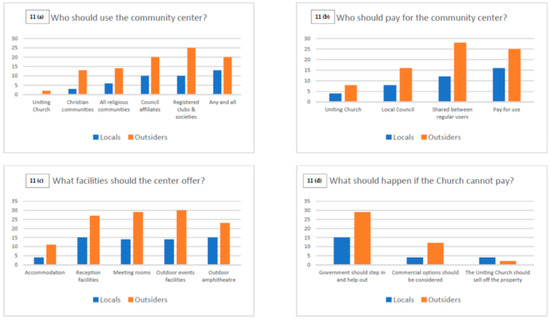

Four sets of multiple-choice questions relating to the operational nature of a possible Uniting Church initiated community center were asked. Multiple answers were available to respondents for each question. The results are summarised in Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11.

Figure 9.

‘Listening Post’ statistical data for Questions 4 in (a) and 5 in (b).

Figure 10.

‘Listening Post’ statistical data for Questions 6 in (a) and 7 in (b).

Figure 11.

Statistical response summaries for the 64 returned questionnaire surveys.

On the question of ‘Who should use the community center?’, response proportions between locals and non-locals were similar. The major observation was that while the Uniting Church is principally a religious institution, the response trend favoured making the proposed Community Centre available to the broader community, its clubs and societies, as well as to others generally. The statistical patterns included: almost 90% (51) wanted it to be available to independent organisations for any legal use; 50% (28) wished local council support and use for the community centre; 45% (26) wished for it to be used for religious community uses only; 28% (16) supported all uses; 7% (4) wanted it to be used for religious uses solely; 3% (2) wanted only the government to use it. From these responses, the majority of participants suggested that (19) the Lorne Community Centre should be made available for anyone for legal use. The statistical patterns per Option for this question are depicted in Figure 9.

Participants to the survey also offered their written thoughts on the proposal and the strategic planning and economic dilemma faced by the Church. One participant, recognizing the dilemma, wrote: “As a fulltime local resident, rate payer and practicing Christian, I cannot see how this project is ‘good stewardship.’” [original italics]. Another interviewee candidly expressed the dilemma as a dichotomy: “... a community of Christians … to grow Christianity … [or just] for the welfare of the community[?]” Indeed, Lorne already offers community facilities. The Lorne Leisure Centre caters for meetings, functions and theatre events, with an 80-seat capacity, as well as offering its mainstay of a sports stadium [31]. It has a kitchen, large parking area and multi-purpose rooms [32]. Additionally, the Lorne Community House is the result of successful lobbying for a grant to build a Community Centre. It was opened in 1999, and offers a good range of general interest and educational programs. In 2015, it came under the governance of the Lorne Community Hospital, with access to the resources in management and finance that the Hospital has [33]. The possibility that Lorne is already sufficiently catered to by present community facilities was also noted by a survey interviewee: “There is already a community center in Lorne. With a population of 900, why is a second center needed?”

Consistent with the sentiment that the Community Centre should not be narrowly religious in its purpose, on the question of ‘Who should pay for the community center?’, respondents felt the financial burden should not lie with the Uniting Church. Many felt the Surf Coast Council should support the Centre, while the majority felt costs should be shared between its regular users—those registered clubs and societies previously identified as future main patrons. The statistical patterns included: 86% (50) of replies suggesting that the cost should be paid by the ones who used the community centre or rental incomes; almost 40% (23) wanted the local council to pay the running costs; only 12% wanted church to pay the cost; and, only 5% wanted church to pay the cost solely. The majority, with 31 votes (51%), stressed that if you are the ones using the centre, you should be paying the running costs and only 5% of participants agreed to all options. The statistical patterns per option for this question are depicted in Figure 10.

Even so, the Community Centre represents a substantial financial burden—both in its initial cost, as well as in regards to its on-going running and maintenance expenses. Thus, if the community organizations for whom the Centre would be intended, fail to engage in its use, or to support it financially, the liabilities incurred on the Uniting Church would be more than its congregation could sustain. In such an event, a final question was asked: ‘What should happen if the Church cannot pay?’ Respondents overwhelmingly felt that the financial burden should not fall on the Uniting Church. Rather, it was felt that the government should step in and help. The statistical patterns included: 75% thinking that government should step in, and 93% of these participants thought it that it should be solely the government’s liability; 24% supported re-the evaluation option whereas only 10% supported the selling option. No participant agreed to all three options together. The statistical patterns per Option for this question are depicted in Figure 10.

On the question of ‘What facilities should the center offer?’, responses favoured supporting secular activities, such as receptions and meetings. A strong showing for facilitating outdoor events such as concerts and music festivals also featured, as did markets and fairs. Additional comments on how the Centre should be used interestingly offered a complete spectrum of special interest demographics: child care, children’s play groups, adolescent support initiatives, women’s get-togethers, mothers’ groups, men’s shed and retreats for the elderly. The least favoured option was ‘accommodation.’ Though one respondent suggested the Centre could be used as a refuge for the poor and homeless (which is a problem in Lorne), the majority believed that the wide choice of hotels and guest houses in the area negated this consideration. Again, preferences between locals and non-locals across all responses were aligned. The statistical patterns included: participant observations that both external and internal amenities are on high demand (~85%), whereas accommodation was only suggested by 25% of participants. Statistical patterns per Option for this question are depicted in Figure 10.

Figure 11 provides tabulated statistics for the four core questions discussed above.

The message returned from the structured questions and additional comments is that St. Cuthbert’s Uniting Church is a venerated heritage icon, and that it should be conserved. This is a conclusion that would be expected from a participant congregational audience, if this was the focus of the questionnaire and ‘pavilion’. However, because this pavilion was erected on a public thoroughfare accessed by all Lorne residents and tourists, the statistical data is more skewed towards respecting the existing structure and encouraging its use as nodal community centre in the main street of Lorne.

Additionally, though a religious institution, the proposed Uniting Church’s Community Centre’s purpose should not be narrowed to serve only its congregation. In line with the sentiment that the Church’s heritage ‘belongs to all,’ so to prevails the sentiment that it should be accessible to all. As quid pro quo in offering the Community Centre to the Lorne community at large, interviewees took the view that the costs should be borne by those who used its facilities. Indeed, in developing this most idyllic of sites to serve as great a cross-section of the community as possible, people felt that the St. Cuthbert’s Community Centre proposal should be directly supported by government planning assistance and financial assurances.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The St. Cuthbert’s Uniting Church is a venerated heritage icon. This is true not only of its physical architectural legacy, but also of its social place in the Lorne community. People want that legacy conserved and they want it continued. However, if St. Cuthbert’s is to retain a central role in Lorne society as a living institution, it must adapt to broader community expectations; to some extent, that means reconciling itself to increasingly secularised values.

The workshops facilitated by Deakin highlighted a number of issues. Firstly, the Uniting Church congregation is looking to retain its Christian values, and to express them by giving back to the community.

Secondly, however, the congregation recognised it was under threat. The congregation is aging and is not being renourished. On the one hand, the younger generation is less committed to traditional Christian spirituality engagement and Church attendance, while it was pointed out that the more traditional Christians felt alienated by a waiving of conservative Church values; acceptance of women into the Ministry, rapprochement with other denominations, dilution of Christianity’s core ‘fire-and-brimstone’ teachings.

Thirdly, the workshops revealed a lack of congruity between those who wanted and would be impacted by the building of a Community Centre, and those with the authority to make it happen. An analysis of the problem through ANT made clear that those with the will do not hold the power, while those with the power had no interest. It is the distant, somewhat detached, Church hierarchy that determines at arm’s length the developmental priorities of its portfolio of properties, and until and unless the passion for change displayed by the Lorne congregation can be channelled towards awakening a ‘buy-in’ commitment from the upper echelons of the Church and government, nothing will likely come of their aspirations.

Uncovering this disparity, however, offered the seed of an Action Plan; and that realization was valuable. It was agreed that the congregation, as instigators of the idea for a Centre, had to accelerate their efforts and lobby strongly to the powers that be—government, financiers and the higher Uniting Church authorities.

This led to a fourth conclusion. St. Cuthbert’s needs a solid marketing and business plan; one that begins by properly identifying those niches of latent need that the Uniting Church might cater to. This could be open-air music festivals—likely very appealing given the property’s sloping site facing the beach. It could also be something more closely aligned to works of Christian charity. The median house price in Lorne is an astonishing AUD$1.29 million [34], and this has exacerbated the levels of poverty and need in long-time locals without capital assets [35,36].

Properly identifying a latent range of community-oriented services that the Church might fulfil, and then sifting through these to determine which properly align with Uniting Church values—and even which might offer opportunities to consolidate the Uniting Church’s values within the community—suggests itself as a way forward. As it proceeds to do this, the Church should consolidate its partnership with local council and seek the endorsement and backing of senior Church authorities to push forward its vision for a Community Centre.

Ultimately, what stands out is people’s sympathy and support for St. Cuthbert’s aspirations to be at the heart of a thriving Lorne. As one interviewee put it:

“The church needs to be protected at all costs.”

Author Contributions

I.M., M.B.L., S.S., G.C., H.X.L. and O.T. conceived and designed the experiments; I.M., M.B.L., S.S., G.C., H.X.L. and O.T. performed the experiments and analysed the data; I.M., M.B.L., S.S., O.T. and D.S.J. wrote and edited the paper.

Funding

This research received no external funding except an AU$9000 research incentivation grant from the School of Architecture & Built Environment, Deakin University, for integrated design framework research projects to support community partnerships. This project has been subject to an approved Deakin University human ethics application coded STEC-41-2018-LUTHER entitled “On a Mission: A Community Centre for Lorne” dated 7 November 2018.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Martin Butcher for his consultative work in facilitating and reporting on the St Cuthbert’s workshops, and of course to the Lorne Uniting Church congregation for their participation. Acknowledgements also to architect Stewart Seaton, who consented for images of his design and model to be included in this article, and Sam Coulson, Treasurer of the Lorne Uniting Church, for granting permission to publish an old image of the Church held in the Church archives.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest, and while S.S. was the architect that authored the designs, since obtaining a work contract with Deakin University he is no longer employed by the Church in any capacity.

References

- Wood, G.A. Lorne and St. Cuthbert’s Church; Uniting Church: Geelong, Australia, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Victoria. Surf Coast Planning Scheme (2019 Vers.). Available online: http://planning-schemes.delwp.vic.gov.au/schemes/surfcoast (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Victoria. Planning & Environment Act 1987. Available online: http://classic.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/vic/consol_act/paea1987254/ (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Hedstrom, P.; Swedberg, R. Social Mechanisms: An Analytic Approach to Social Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lovric, N.; Lovric, M.; Konold, W. A grounded theory approach for deconstructing the role of participation in spatial planning. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 87, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2016 Census: Religion. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/mediareleasesbyReleaseDate/7E65A144540551D7CA258148000E2B85 (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- UCA (Uniting Church in Australia). About the Uniting Church in Australia. Available online: https://assembly.uca.org.au/about/uca (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- CRA (Christian Research Association). Charting the Faith of Australians. Available online: https://cra.org.au/ (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Smith, O. The World’s Most and Least Religious Countries, in The Telegraph. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/maps-and-graphics/most-religious-countries-in-the-world/ (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- UCA (Uniting Church in Australia). History of the Uniting Church in Australia. Available online: https://nswact.uca.org.au/about-us/our-history/ (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics). Cultural Diversity in Australia. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2071.0main+features902012-2013 (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Williams, W. Growth and Change in Australian Charities. PRObono Australia. Available online: https://probonoaustralia.com.au/news/2018/05/growth-change-australias-charities/ (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Australian Charities and Not-For-Profit Commission. Annual Report 2017–2018; Australian Charities and Not-For-Profit Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. On Actor Network Theory. Soz. Welt 1996, 47, 369–381. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B.; Yaneva, A. Give me a gun and I will make things move: An ANT’S view of architecture. In Explorations in Architecture: Teaching, Design, Research; Geiser, R., Ed.; Birkhauser: Basel, Switzerland, 2008; pp. 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Martek, I.; Lozanovska, M. Consciousness and Amnesia: The Reconstruction of Skopje Considered through Actor Network Theory. J. Plan. Hist. 2016, 17, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. We Have Never Been Modern; Hemel Hempstead: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods; Sage: Oakland, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Westin, O.; Roberts, H. Interventionist Research—The Puberty Years: An Introduction to the Special Issue. Qual. Res. Acct. Manag. 2010, 5, 5–12. Available online: https://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/pdfplus/10.1108/11766091011034253 (accessed on 24 January 2019). [CrossRef]

- St. Cuthbert’s Uniting Church. St. Cuthbert’s Home Page. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/pages/St-Cuthberts-Uniting-Church/203111253034633 (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Surf Coast Shire. Economic and Population Profile, 2014. Available online: https://www.surfcoast.vic.gov.au/Community/Businesses/Economic-and-population-profiles (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Page, A. The Economic Value of the Surf Industry to the Surf Coast Shire: Final Report, 2014. Available online: https://www.surfcoast.vic.gov.au/Community/Businesses/Economic-and-population-profiles (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- ABS. Australian Population Census. 2016. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/Population (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Google. Google Maps. Available online: www.google.com/maps (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Stirling, D. History of Lorne and the Great Ocean Road, Lorne Historical Society. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/pg/LorneHistoricalSociety/posts/?ref=page_internal (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Gregory, E.B.; Gregory, M.L.; Koenig, W.L. Coast to Country: Winchelsea—A History of the Shire; Hargreen Publishing: North Melbourne, Australia, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Stirling, D. Lorne: A Living History; Adams Print: Breakwater, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cecil, K.L. Lorne: The Founding Years to 1888; Lorne Historical Society: Lorne, Australia, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, R.L. Beach, Bush and Blessings—St. Cuthbert’s Lorne: One Hundred Years 1892–1992; Centenary Committee of St. Cuthbert’s Uniting Church: Lorne, Australia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- UCA (Uniting Care Australia). Uniting Care Australia, 2018. Available online: https://www.unitingcare.org.au/ (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Surf Coast Shire. Lorne Leisure Centre, Surf Coast Shire. Available online: https://www.surfcoast.vic.gov.au/Experience/Venues-for-hire/Lorne-Leisure-Centre (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Kellaway, C.; Rowe, D. Surf Coast Places of Cultural Significance Study; Surf Coast Shire: Torquay, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- NearMap. Available online: www.nearmap.com.au (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Lorne Community House. Lorne Community House. Available online: https://lornecommunityhouse.org.au/ (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Realestate.com.au. Lorne—Median Property Price, realestate.com.au. Available online: https://www.realestate.com.au/neighbourhoods/lorne-3232-vic (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Hanrahan, C. Think there are no homeless people in your area? Think again. In ABS News; Australian Broadcasting Commission: Sydney, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).