1. Introduction

In an age of rapid social, cultural, and economic globalization, the world is currently experiencing a historically unprecedented rate of urbanization [

1]. New geographic patterns are emerging as the result of rapid rural migrations, new economic opportunities, and enhanced mobility of populations, particularly as the result of automobile technology [

2,

3]. As a result, cities have dramatically expanded spatially, resulting in urban transformations and structural changes, often resulting in low-density ‘sprawl’ development. These changes are now posing new kinds of threats to urban character, identity, livability, and sustainability [

4]. To address these large-scale structural changes, a number of models of reform have been advanced within urban planning and design. Some reformers point to historic models of urbanism that have been superseded by modern urban development but are once again advanced as viable solutions for contemporary social, economic, and environmental problems, where it is argued that modern planning and design have failed. Most recently, these ideas have been reflected in the “New Urban Agenda” outcome agreement of the United Nations’ Habitat III conference, which proposes more compact, inter-connected, and walkable networks of public spaces that are more characteristic of historic urban patterns [

5].

Other reformers point to the need to address large-scale historic urban decline and ‘shrinking cities’, a global phenomenon that is especially prevalent in post-industrial cities in Europe and the USA [

6], defined by employment decline, subsequent population decline, and the resulting economic downturn sustained over a four to five-decade period [

7]. In this paper, we focus in particular on the example of Detroit, Michigan, USA as an emblematic example (See

Figure 1). It is important to recognize, however, that shrinking cities are not only shrinking, they are often growing at the same time in their sprawling peripheries, creating ‘urban archipelagos’ where growth and revitalization occur parallel to extreme ongoing decline. As in the case of Detroit, many such shrinking cities have experienced harsh economic, social and spatial structural changes, as the result of economic and cultural globalization, de-industrialization, a diminishing public sector, increased mobility, and tough national and international competition. These cities must find strategies to capitalize upon their inherent qualities and their own distinctive local identity, both to remain economically competitive with other cities, and also to improve the local quality of life.

We examine here the option of using urban planning and design based upon local urban heritage as a means to revive these post-industrial cities, towns and neighborhoods. In such an environment, what are the advantages and constraints for creating a vibrant public realm? How can heritage contribute in a declining city that has little or no extant public realm left? Do urban planning and design models based upon local heritage patterns offer still-valid, effective measures for the reinvention of cities and towns that experience structural change? If so, what are the methodologies by which they can be identified and regenerated successfully? In practice, how do different urban planning and design paradigms treat the past (heritage) in the present and future to create ‘place’?

These questions come at a time when urban heritage is widely seen as an important feature in many city branding and recruitment strategies, aiming at attracting new tourists, residents and investors. But the question arises how such a strategy can go beyond superficial marketing of existing heritage assets, and actually use local heritage patterns to transform the spaces of the city into more lively, attractive and economically successful places. As we will discuss shortly, the present view is that heritage is a static contextual feature reflecting the past, not in any sense a potential active ‘generator’ for future development. By contrast, we will argue that an integration of key ideas and approaches from different competing paradigms in urban planning and design, combined with a focus on urban heritage fabric as a generator of future city landscapes, could lead to a new approach for revitalization, which we term ‘heritage urbanism’.

The research conducted for this paper is a combined strategy, mixed-methods approach [

8], and an explorative search [

9] for empirical evidence using a descriptive process of conceptual modelling [

10]. This included elements of the case study research method [

11]. such as analysis of primary documents and plans from city and state official reports, as well as developer publications and releases, and secondary sources such as newspaper and magazine articles, and relevant websites. This paper thereby seeks to illuminate larger trends through a singular case study [

12], where multiple field study trips were made to Detroit heritage sites in the period from 2011 to 2016. The method of direct observations [

13] was used on the ground, which included a visual mapping analysis of first-hand experience of the projects as well as recorded observation memos and photographs of different heritage entities in Detroit.

2. Key Differences within Existing Competing Urban Planning and Design Paradigms

Throughout the last three decades, a number of normative design models have emerged to claim leadership in the practice of urban planning and design. These design models, and the movements behind them, have already begun to have a notable impact on the form of our built urban environments. The specific ideals dominating today’s urban planning and design discourse have been examined and defined in various ways, such as territories of urban design [

14], urban design force fields [

15], integrated paradigms in urbanism [

16,

17], typologies of urban design [

18], “60 newest urbanisms” [

19], “five ideals in urban planning and design” [

20] as well as others. In our investigation we build upon these “classifications”, and from this particular investigation on Detroit, we can readily identify seven distinct design movements (urbanisms with specific content prefixes), each with its own distinct models, that dominate today’s urban planning and design discourse: New Urbanism, Post-Urbanism, Re-Urbanism, Landscape Urbanism, Everyday Urbanism, Placemaking Urbanism and DIY/Tactical Urbanism.

New Urbanism focused on walkable mixed use, multi-modal transportation, an intimate connection of buildings and public space, historic regeneration, public involvement, and a supportive physical framework for sustainable growth [

21]. Post-Urbanism is philosophically aligned to post-structuralism, and practices of postmodernist, deconstructivist architecture, and could be labelled as avant-garde generic hybridity, with a focus on reinvention and restructuring, ignoring past precedents and gaining inspiration from the future. It is a type of ‘starchitecture’ or neo-modernism urban development that bypasses contextualism, and focuses on the spectacular buildings that in turn are supposed to be seeds of new (de)contextualism. Post-Urbanism does not result from a coherent and organized movement in the way that New Urbanism does, but is rather a type of architectural led anti-urbanism practiced by internationally recognizable “star architects” such as Koolhaas, Gehry, Liebeskind, and others. Re-Urbanism, on the other hand, is a high-density market-driven urbanism of new economic geographies. In essence, it is simply an adaptation to the existing urban forms, a sort of contemporary urban design and architecture with historical precedents. Landscape Urbanism is a theory of urban planning arguing that the best way to organize cities is through the design of the city’s landscape, rather than the design of its buildings. Layered onto that ideology is also a new ecological sensibility which recognizes the natural landscape as the starting point in the design of cities and with a distinct emphasis on horizontal surfaces and modes of representation. Everyday Urbanism could be described as vernacular spatiality with a bottom-up approach all sharing in common the emphasis on everyday life. More than any of the other paradigms and ideals listed here, this one focuses on the lived and shared human experience of urban life rather than on the design of architecture or public space. Everyday Urbanism looks at the urban condition as it is and embraces the ordinary. While it is a self-declared non-design practice, it is a practice rooted in the conditions created by urban life in the built environment. Placemaking Urbanism is a term identified it as a third tradition in urban design thought which is simultaneously concerned with the product-oriented ‘hard city’ of buildings and space and the process-oriented ‘soft city’ of people and activities. Placemaking is rooted in the idea of a collaborative process by which we can shape our public realm in order to maximize shared value. Placemaking facilitates creative patterns of use, paying particular attention to the physical, cultural, and social identities that define a place and support its ongoing evolution. Finally, DIY/Tactical Urbanism approaches are often associated with other terms and activities describing bottom-up projects or interventions such as guerrilla urbanism, guerrilla gardening, Park(ing) Day, open streets, insurgent practices, pop-up urbanism and more. This approach to neighborhood building and activation usually uses short-term, low-cost, and scalable interventions and policies, such interventions that share a common agenda of promoting people-centered places.

Treatment of Heritage Between the Competing Urbanisms

A key differentiation in these seven urban planning and design ideals is their respective ways of treating past precedents. For example, Post-Urbanism connects to an idea that the past has no real relevance for future development and is based in a rejection of, or a freedom from, traditional ideas about what characterizes the urban environment and urban planning and design. Instead, it emphasizes, in particular, architectural monuments and iconic buildings that claim to be innovative and to express a new era, often this involves only the building site, a fragment of the urban environment disconnected to the surrounding context [

22]. The role of flagship projects, such as the Landscape Urbanism claimed High Line remains under debate. However, policymakers can critically reinterpret these projects as the exploration of new cultural places, involving a broader set of actors and interests and fostering a more sustainable evolution of urban landscapes [

23]. This reflects directly the heritage of the future—which is being created in cities and towns by ‘starchitecture’—new iconic flagship architecture. New Urbanism, on the other hand, is based on ideals and qualities from the time before the modernist planning shift and is aimed at re-creating these qualities in contemporary urban planning and design. It includes ideas of mixed use and an emphasis on public space and environments suitable for pedestrians alongside the creation of public places. Moreover, in Everyday Urbanism emphasis is put on the present and, thus, ideas about the future and approaches to the past are not important at all. Everyday Urbanism can in this way be connected to an idea that society is the unintended consequence of peoples’ actions, rather than urban planning and design efforts, and as such favors a cultural preservation approach emphasizing narratives of local history and local character. DIY/Tactical Urbanism is a relatively new way of dealing with urban heritage and focuses not on long term preservation efforts but on citizen-led actions to engage with the history of a site in order to produce ideas and solutions for future urban improvements in the public realm [

24]. Placemaking is in some ways similar to DIY/Tactical but in the context of Detroit it has become a hallmark in the urban revitalization of the downtown core, transforming public places through incremental changes. Placemaking, along with Everyday Urbanism and DIY/Tactical Urbanism highlights “human capital” as a value beyond physical structures, and represents a turn away from what Fainstein calls a “formalist physical solution to urban decay” ([

25], p.425). Practitioners of urban development should know by now that there are no strictly structural answers to the city, as was once believed by modernists and those who used this solution for cities like Detroit by trying to build their way out of the challenges they faced ([

3], p. 53).

In addition, as Louis Wirth [

26] and Fran Tonkiss [

27] observed, cities are fundamentally social forms, and only secondarily built forms. City-making is a social process and the intricate and close relationship between the social and physical shaping of urban environments is crucial for creating public spaces which shifts the focus more on the “life between buildings” ([

28], p. 25) as well as shifts towards the smaller infrastructure which influence everyday behavior. The important thing to keep in mind, as Calthorpe [

29] observes is, while each place is unique, there are universal human traits that set the fundamental DNA of great cities: human scale, diversity of action, and social interaction. In urban planning and design today, there is a need to understand how to better integrate different paradigms, approaches, practices and how to harness the generative possibilities of the urban fabric as an asset for future urban development. Finally, a combination of different key ideas from the competing urban design paradigms that can give us explanations and answers as well as solutions for public realms, coupled with explorations in key elements of different urbanisms where a nuanced understanding of public space is brought in, may be an approach that many of our cities are missing at this moment in time. In

Table 1, all seven ideals are, in short, positioned vis-à-vis the past and urban heritage.

3. Case Study of Detroit, USA: Heritage, Decline, and the Awakening from Ashes

“…the history of economic development explains the physical shape of the city over time”.

—Dolores Hayden, 1988 [

30]

Perhaps nowhere are the contemporary challenges of heritage and urbanism more clearly on display than in the city of Detroit, Michigan, USA, where for decades, the forces of decline, abandonment, and decay have taken a toll on the physical structures and urban fabric of Detroit’s urban core. The causes of the city’s decline, including federal policies, racial tensions, municipal mismanagement, economic over-specialization around automobile manufacturing and subsequent economic stagnation have been well described in previous research (see, for example, [

31,

32,

33,

34]). In addition to serving as a textbook case for urban decline, Detroit is also a prototypical example of efforts to revitalize cities under the ‘urban renewal’ programs of the mid-twentieth century, and also one of the first to attempt it [

35].

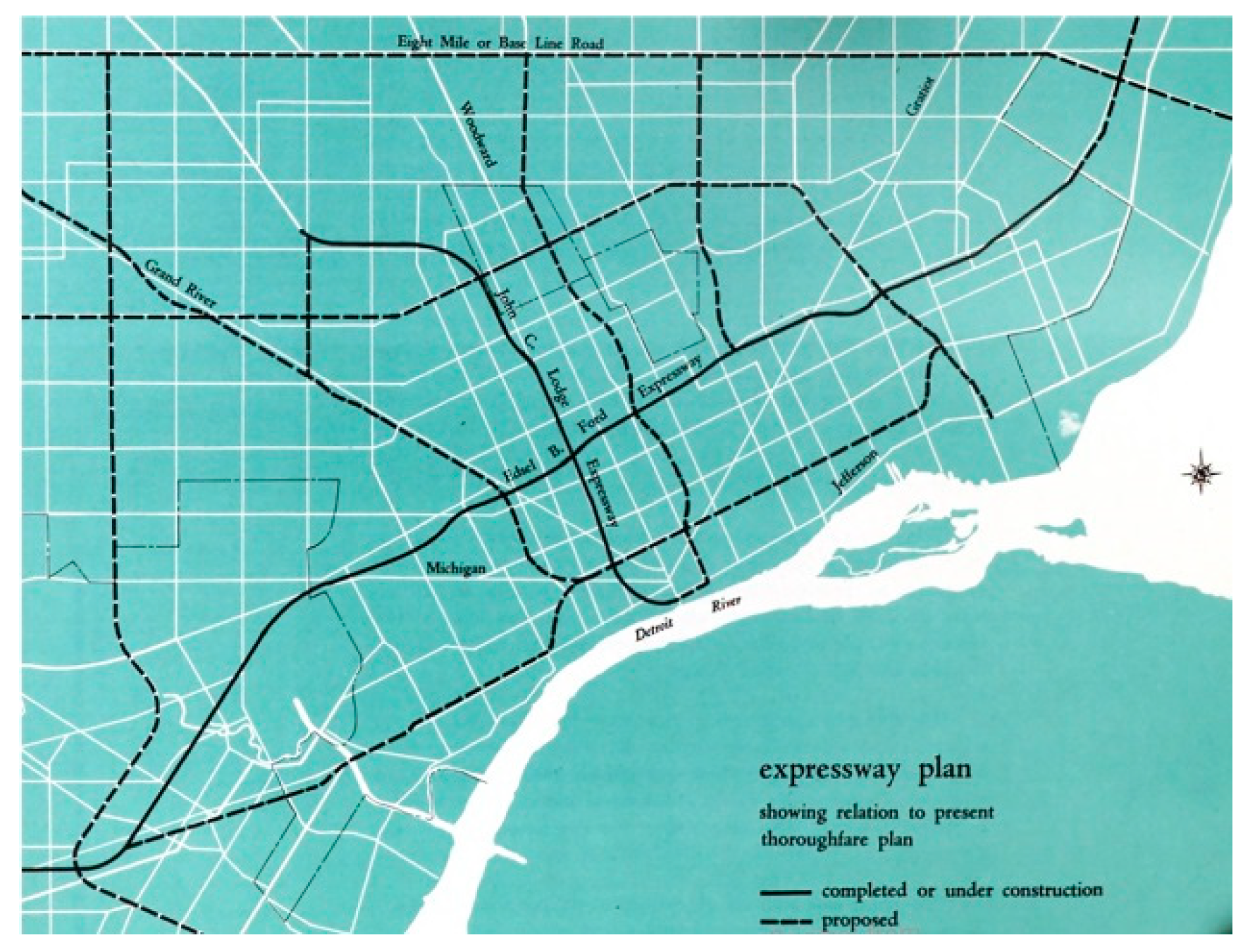

By the early 1940’s Detroit officials were thinking about how to address the problems of “deteriorating community facilities, loss of the middle class, downtown decline, clogged streets, industrial exodus, inadequate housing, racial conflict” ([

36], p. 17). In response, municipal leaders were beginning efforts to fight urban decline, and to rebuild or redevelop affected areas both in the core and outside the core in order to recreate the prosperous city of before [

36,

37]. These programs deliberately destroyed large swaths of the city’s historic urban form to make way for public housing and civic complexes under the architectural and planning principles of modernism, the prevailing paradigm of the era. Importantly, after urban renewal in this era, the city was to be accessed not by public transit or by a walkable street grid, but by automobile and buses. Accordingly, large freeways were built adjacent to these sites, cutting through the historic urban form and creating large barriers between neighborhoods (See

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

At the time, Detroit officials saw the interventions of urban renewal as signs of success and progress [

37], not as creating unforeseen side-effects which visionary Jane Jacobs had already described as far back as the late 1950’s [

38]. She described an intimate connection between the city’s loss of economic diversity (in the early 20th Century) and its subsequent loss of diversity in urban form, in a process she termed “the self-destruction of diversity.” What is interesting for our purposes here is the subsequent alterations of urban form, and their impacts in mitigating, or—as was overwhelmingly the case—hastening the “slumming” processes that Jacobs so memorably described (1961) [

39].

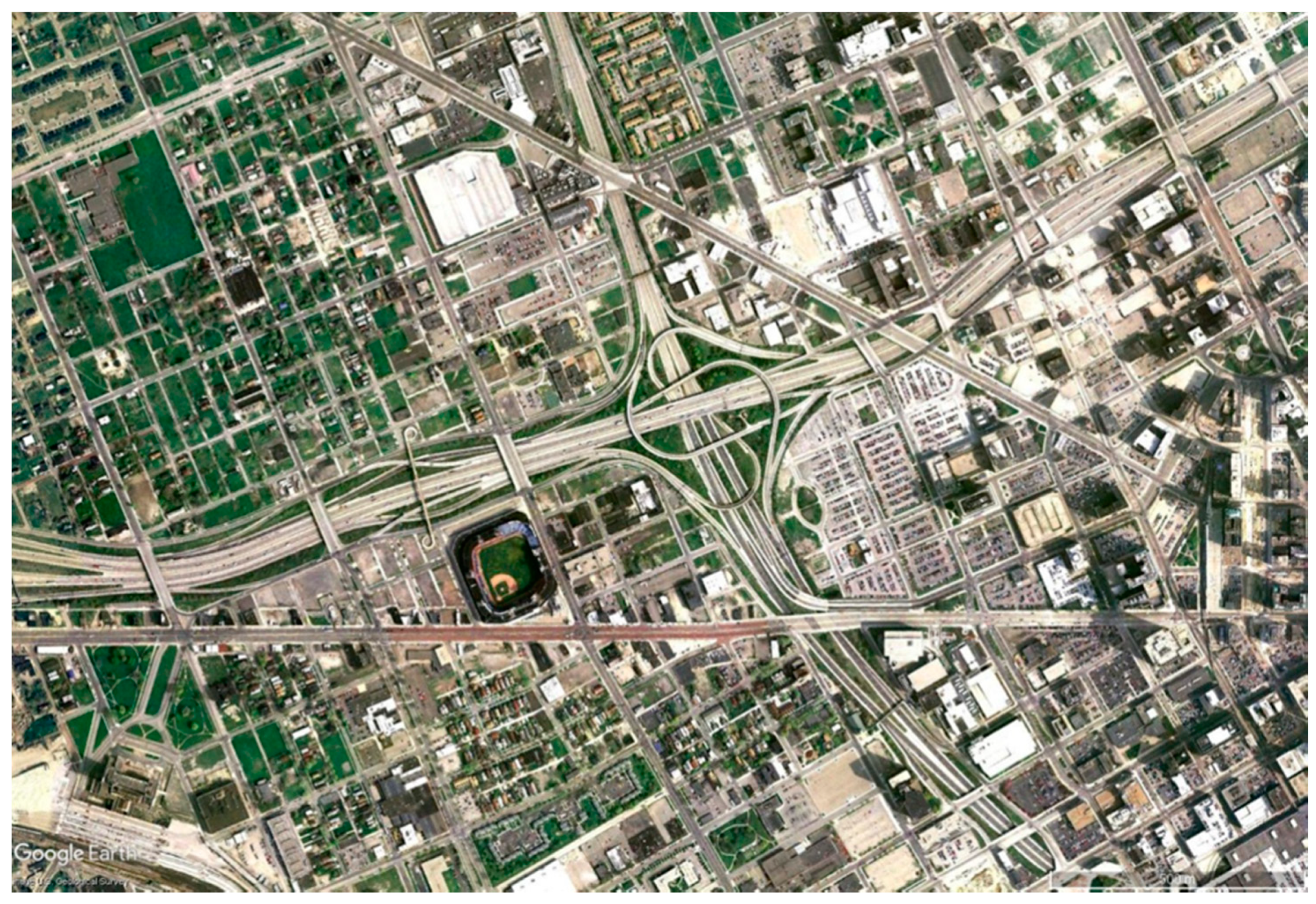

Where once avenues and streets acted as vital corridors of economic and social activity connecting districts, these new freeways made clear and distinct barriers which are still felt today and have since shaped the city and contributed to the blighted landscape. Jacobs described the consequences well in her chapter on “The curse of border vacuums”. She saw the impacts of such isolation and fragmentation as key “ingredients in the decline and decay” of American cities, because of the way that blight occurs along borders, pulling away the life of each zone by disconnecting it from the city grid. As Jacobs wrote, “the root trouble with borders is that they are apt to form dead ends for most users of city streets” ([

39], p. 259). This is a clear example of the important role of connectivity of urban form in the social and economic health of a city.

Jacobs noted that the resulting decay can create a runaway process: as the blocks around the border become less attractive and less active to the point where they quickly lose value and begin to deteriorate, the “slumming” spreads to adjoining neighborhoods too. Jacobs writes that “oversimplifying the use of the city at one place, on a large scale, simplifies the use which people give to the adjoining territory too, and this simplification of use means fewer users, with fewer purposes and destinations at hand” ([

39], p. 259). Today we can see this dynamic across Detroit, with empty sites and abandoned buildings where people, commerce and industry once thrived. In many sections of Detroit, there is little to no built form remaining on top of the layers of streets and sidewalks, and sometimes all that remains is the basic blocks, lots and street patterns, in other words, the basic elements of the earlier urban morphology remain, although degraded by decades of urban renewal and subsequent urban decline.

Adding to the problem is the lack of incentive to re-use existing buildings and other historic structures. In Detroit in previous decades, all of the built forms and fabrics from buildings to streets and public squares have been eligible for easy demolition. Even in the wake of a more recent economic rebound, retention of existing heritage is still a major challenge, as evidenced by ongoing losses of historic structures. A notable example is the early 2016 loss of a historic landmark tower, in a historic designated district, to make way for a new sports arena [

40].

Nonetheless, there is a growing awareness of the continued value of historic buildings and streetscapes. Today, we see a strong renewed interest in urban living and urban experiences desired by non-city dwellers, and a renewed interest in aged buildings and public spaces (See

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). There is increasing demand for the qualities and characteristics that old buildings possess, notably by technology businesses and their employees. They increasingly seem to value the characteristics that can only be obtained through time and history, and can never truly be replicated or imitated. Important buildings have been saved recently, including the Metropolitan Building and Wurlitzer building, which just a few years ago could have easily been demolished. In part, then the attitude towards preserving buildings in Detroit is changing due to consumer demand, but also because of a growing recognition of economic, ecological and cultural benefits. As this trend continues, it would appear that the next steps would be to consider more than the buildings, but also the spaces and urban patterns around them.

The interest in aged buildings also extends to the walkable historic character of their neighborhoods. Many of the hottest and trendiest restaurants, small plate bistros, café’s, craft cocktail bars, and boutiques are opening in the remaining and adapted old buildings, which are often sited along streets that offer some degree of walkability. It seems that everywhere in Detroit, aged buildings are the first preference to building new, especially at the scale of small and local businesses. The same could be said of the city’s housing stock which is largely built pre-WWII. Neighborhoods with older buildings and walkable infrastructure are in high demand, with rents steadily increasing in neighborhoods such as Woodbridge, Midtown, Corktown, West Village, are all high on the list of prospective residents. This seems to suggest that not only aged buildings, but also the settings they are in are adaptable over time and now again are in increased demand, and should be seen as an asset in future development. Indeed, Jacobs [

39] argued that “aged buildings” formed one of four key “generators of diversity”—not as preserved specimens of history, but as dynamic elements of a healthy city.

Organizations like Preservation Detroit and others have increased their services and activities demonstrating an overall growing awareness to preserve historic structures by educating the public and involving citizen participation. In a sense, the increased flow of visitors to Detroit’s neighborhoods, downtown, Eastern Market area, and anywhere where old buildings have been adapted to new uses, could be seen as a type of ‘heritage tourism’, partially replacing what before was ‘ruin porn tourism’. When the City of Detroit hosted public discussions in 2017 concerning plans to create a comprehensive neighborhood strategy in northwest Detroit, historically significant buildings in the district were featured and recognized as critical assets in redevelopment, in addition to attention to streetscapes, landscape design, and economic development [

41]. This is in sharp contrast to previous generations of urban redevelopment which sought to erase the past, including even the basic geometry of the urban layout and street network. A notable example in Detroit was the famous and controversial Lafayette Park development of the 1950’s, an urban renewal project of a former African-American neighborhood where original street networks and even street names were not retained.

While there are many successes to point to in preservation of cultural buildings (Fox Theater 1988, Detroit Opera House 1996, Gem Theater, 1997), and of landmark buildings (The Book Cadillac Hotel, 2008), the ongoing establishment of historic districts (Cass Park H.D. 2005), and the ongoing focus on revitalizing historic public places in the urban core such as Campus Martius, Cadillac Square, Grand Circus Park, Capitol Square, there has been little attention in treating the urban fabric as a resource for conservation, preservation, and to be utilized in rebuilding the city. It would seem, then, that the city has an excellent opportunity to expand its conception of heritage as a resource for future development. However, as we will examine in the next section, a key barrier remains, in the form of existing attitudes to the status of heritage as a contemporary resource.

4. Limitations on Heritage: Static Relic or Dynamic Asset?

The common method employed in urban heritage management is identification and protection of monuments, specific objects and well-defined areas that are especially valuable from a historical perspective. Hence, the management is based on expert values within academic fields traditionally concerned with urban heritage, for example, art history, architecture and archaeology. These expert values are assumed to correspond with values in society at large. On a general level, it is reasonable to assume that there is a common view among various interests that conservation activities are worthwhile. However, this is not self-evident in a specific case, in which concrete values of different kinds have to be weighed against each other. As expert values they are decided upon independently of values held by other interests, the latter often having completely different perspectives concerning the urban environment—for example, perspectives held by urban and regional planners, real estate owners and developers and of course, local citizens. In that sense, the role of current public heritage management in contributing to new urban planning and design is ambiguous and limited [

42].

The architecture profession also has a highly circumscribed view of the role of heritage in generating new structures. In the years following the destruction of WWII, the Venice Charter of 1964 [

43] emphasized authenticity and added a requirement that new constructions “bear a contemporary stamp,” a phrase widely interpreted as requiring new construction to reflect the contemporary styles of their own time, and ignore—or actively clash with—precedents set by heritage structures. Thus, the overriding goal is to identify, isolate and protect historic structures, as historic structures that stand apart from newer ones. They are not to be conceived as inter-woven with contemporary structures, or in any real sense ‘generators’ of contemporary patterns or designs. Indeed, that would be ‘pseudo-historical’ and such confusion of past and present is to be avoided at all costs.

In a sense, this is a kind of ‘functional segregation,’ consistent with the 20th Century model of ‘functional segregation’ that proposed separation by use, by form of transport, and by position of buildings in a clear ‘functional’ layout. The role of historic structures was also equally ‘functionally segregated.’ The Venice Charter reflects a prevalent 20th Century conception of heritage structures. This conception was formulated in perhaps the clearest expression in the 1933 “Charter of Athens,” developed by the Congrès International d’Architecture Moderne, or CIAM, a highly influential early 20th Century movement that largely set the blueprint for modernist city design. The Charter of Athens was later published by the architect Le Corbusier (1943). Among its key points is the following:

The destruction of the slums around historic monuments will provide an opportunity to create verdant areas. In certain cases, it is possible that the demolition of unsanitary houses and slums around some monument of historical value will destroy an age-old ambience. This is regrettable, but it is inevitable.

In other words, we should mourn little for the loss of historic pattern and character, so long as we save small and noteworthy relics of the past. Nor should we ever consider re-incorporating or restoring demolished historic patterns, designs, or characteristics of any kind:

Never has a return to the past been recorded, never has man retraced his own steps. The masterpieces of the past show us that each generation has had its way of thinking, its conceptions, its aesthetic, which called upon the entire range of the technical resources of its epoch to serve as the springboard for its imagination...The mingling of the “false” with the “genuine,” far from attaining an impression of unity and from giving a sense of purity of style, merely results in artificial reconstruction capable only of discrediting the authentic testimonies that we were most moved to preserve.

There is a theory of history at work in this passage which is radical and totalizing. Each increment of urban structure is a distinct and self-conscious contribution to history, which can and must be kept water-tight from others, lest we mingle “the false with the genuine”. This absolutist prohibition extends to all aspects of design, to be reduced in this conception to a historic category of “style”: “The practice of using styles of the past on aesthetic pretexts for new structures erected in historic areas has harmful consequences. Neither the continuation of such practices nor the introduction of such initiatives will be tolerated in any form” ([

44], para. 70).

In practice, this conception of historic pattern has meant that the past has nothing dynamic to contribute to contemporary problems of form and growth. We are to “start from zero” with a “tabula rasa”—which means that heritage is nothing more than a museum relic, with no generative role in the present. This conception of history informs much of the current discourse on historic preservation and urban revitalization. Two other documents on heritage management shed light on this evolving discourse. The Washington Charter (1987) [

45] went beyond the individual monument to include historic urban areas, recognizing the threat that urban development posed to urban communities and cultures. The Washington Charter also identified urban form and functions as qualities that contribute to authenticity, but still, it was focused on conservation and preservation. The Vienna Memorandum (2005) went beyond traditional definitions of “historic centers” and included the significance of “the broader territorial and landscape context” and focused on the integration of contemporary architecture and urban development with existing historic patterns and context [

46]. This was an important step forward because it recognized that historic typologies and morphologies in cities are the result of an evolutionary and gradual process, and are worthy of protection.

5. Opportunities in a “Systems Approach” to Heritage

By contrast, in the years since the Charter of Athens (1933), the Venice Charter (1964), The Washington Charter (1987), and the Vienna Memorandum (2005), the sciences and mathematics of ‘systems’ have advanced significantly. As we will see, under this conception of urban history and the evolution of urban form, heritage offers a rather more interesting opportunity. In this conception, the urban environment or urban landscape is a complex system of recognized monuments, modest buildings and other built structures, one could extend the same logic to the public spaces and urban patterns surrounding these buildings as well [

47].

Consequently, a certain structure or object within the system is to a substantial part defined and characterized by the environmental context. Each object has an external impact on the surroundings, which can be negative or positive, and will indirectly impact the understanding and valuation of adjacent objects. In this way, the surroundings, neighborhood, district or city add and compound the value of each object. They form an inseparable ‘system’ that has essentially interrelated parts and form an evolving pattern over time of “organized complexity” [

39].

When considering urban form as a system there is much to be learned from the field of urban morphology studies. Independent of any leading architectural or urban design paradigm, the field of urban morphology, which in the simplest of descriptions is “the study of city forms” [

48], often deals with elements of urban heritage in a systems-wide approach by studying the processes behind physical urban transformations. Moudon [

49] gives three principle elements of Urban Morphology: (1) Form/patterns, “buildings, related open spaces, plots or lots and streets”; (2) Resolution/scale, lot/plot, street/block, city/region; (3) Time/process: transformation and permanence. Brenda Scheer [

50] adds further layers of urban form—Land/topography—as the first determinant layer of urban form.

In addition to asking the question “what is” (in urban form), another useful contribution from the field of urban morphology is to describe “why it is” through an understanding of the processes behind urban transformations, both of these inquiries predicate the next step of investigating what can be done to alter that condition, and to make proposals about how to do that, this is the work of urban design and planning within the broader scope of urban development. Gauthier and Gilliland within their aims to classify and interpret the study of urban form, describe both “internalist” and “externalist” approaches to the field, where “externalist” approach is one that sees urban form as “the end product of processes driven by political, anthropological, geographic, and economic, historical, and perceptual determinants” ([

48], pp. 44–45). Furthermore, Gauthier and Gilliland state that “perhaps the most important contribution of urban morphology to the study of cities has been to show how the built environment can be understood as a “system of relations” submitted to rules of transformation” ([

48], p. 45). This highlights the importance that time and process play in understanding urban decline, loss of urban form, changes in the street network and possible revitalization of the mentioned elements.

Jane Jacobs (1961) also devotes considerable attention to the processes by which cities decline, but also rejuvenate, through connectivity and ease of movement, of people, of goods, and economic activity, by having attraction points that are connected to a grid offering many options for movement, and by diversifying the uses, reasons, and purposes to be in an urban space. As discussed previously, her “border vacuums”—posing the antithesis of this connectivity and fluidity of use—are often created as disruptions of historic patterns in the urban fabric (See

Figure 6) [

39]. When considering how the urban fabric could act as a generative force in urbanism, it is crucial to understand the effects of such disruptions in the historic urban form, and hence, the necessity of conserving and building upon it.

From this point of departure, it seems reasonable to consider the urban landscape as a totality in heritage management, not only within delineated monuments and conservation areas, but also including modest buildings, streets, street networks, the public realm, and the urban landscape as such, all constituting a dynamic ‘urban heritage’. Furthermore, the city is not a museum preserved to represent a single time period, but more like an evolutionary ‘fugue’ of strands from different eras weaving together and recapitulating. Yet a vast majority of the structures in the urban environment have not qualified for preservation activities in traditional heritage management, which tends to focus on historical monuments and well-defined conservation areas. This implies that modest buildings and the general urban landscape, which includes a diverse set of artefacts that are spatially and/or socially linked together, will be neglected. What is needed in urban development planning today is something similar to the Vienna Memorandum (2005) and at the least a robust discussion about urban heritage in urban planning and design aiming at urban development, acknowledging the urban heritage as an infrastructure.

In order to include a broader ‘systems approach’ view on urban heritage in urban development, it is necessary to first examine dynamic and evolving social and economic values, rather than static historical values as defined by experts. While many aspects of social and economic values change, many also do not, and heritage often remains extremely useful and economically viable. Thus, the question is how to define the urban heritage as an infrastructure, a ‘commons’ and a public good, based on how people and businesses use and benefit from its role within the urban environment. This evolution into a more robust mechanism and resource will inevitably require a universalizing approach to urban heritage, that is, an approach that sees heritage patterns as inextricably interwoven with all other aspects of urban structure [

42].

Preservation, conservation, and authenticity are common words in urban heritage management; adaptability and generativity are not. Adaptive reuse has long been a growing trend within heritage management, but this paper argues for an even more aggressive approach. We propose that urban heritage is a commons resource and public good which could be utilized as a starting point in the re-making of cities facing extreme decline, decay, and abandonment. We can see precedents for this approach in the work being done on ‘downtown revitalization/Main Street’ programs in the USA, or with ‘cultural landscapes’ often located within National Parks and Trusts because these focus on more than a singular building or monument and typically deal with urban fabrics. In the following section, we propose an even more explicit and systemic application of urban heritage as a resource to regenerate urban areas and to adapt them to contemporary uses and needs.

6. A New Way Forward: Heritage Urbanism

“When a city is in a crisis moment, there’s a willingness to consider unconventional alternatives”.

—Maurice Cox, Director of Planning and Development, City of Detroit, 2018 [

51]

Thus we arrive at a new normative model for the organization of urban design and architecture, which we term ‘Heritage Urbanism.’ Specifically, we propose that urban heritage is to be considered as comparable to other infrastructures within cities. In that light, the status of this heritage infrastructure in Detroit could today be considered much like other infrastructures in the Motor City, neglected and falling apart, and in need of renewed attention and focus by city officials and planners. A systems approach to urban heritage would focus not on conserving or preserving the urban tissue/fabric of a city for the sake of attracting tourism or locking that section of a city into a certain time-era, but to act as a regenerative layer upon which to develop the contemporary city. The concept of infrastructure is in this sense far more than a technology for delivering resources, such as water pipes or automobile highways. It is, rather, an urban framework, a system on which other sub-systems will evolve and adapt.

Consequently, urban heritage, seen as a system, encompasses not only defined conservation areas and heritage objects, but also tangible and intangible phenomena that link various objects and areas together and contextually generate and reinforce their value in a broader setting. In order to attain and retain sustainable urban heritage, cities and governments, as well as local communities, need to create and nurture buildings, objects, spaces, places, contexts and practices that have embedded meaning and value to them, filled with historical narratives, enriched with local cultures and social interfaces. Urban heritage, as the valued tangible and intangible legacy of the past but also resource for the present and capital of the future, thereby offers, to places like Detroit—and many others—a crucial asset for cities, not just in terms of place branding but much more of a systemic approach to all the aspects of everyday life, as they affect human experience and well-being [

52].

This systems approach to urban heritage, then, defines urban heritage as a foundational infrastructure, and, hence, a public good, comparable with other infrastructures as a frame for people’s daily activities and for business development, especially within the context of urban renewal and regeneration. The first step in a wider regeneration of the city, then, is to recognize the value of this ‘generator of landscapes’ as a powerful but under-appreciated resource. The second step, which is beyond the scope of this paper, is to example specific tools and methods for doing so, here the multidisciplinary field of urban morphology as reviewed in this paper offers potentials for studying and analyzing the city as a system of relations. Typically the loss of historic buildings through demolition, fire, and obsolescence has been well noted (see [

32,

53]), but the consequences relating to the loss of the connectivity of historic urban fabric, including Detroit’s ability to be resilient in the face of economic changes has received far less attention. Further studies would analyze the economic effects of “border vacuums” and dis-connectivity, and would analyze the economic impacts of reweaving the urban fabric in key locations with high potential.

This model would fall in line with the body of well-established research on organic development of areas over time vs. ‘built at once’ developments which have seen so many well-documented post-war failures [

54,

55]. Rebuilding the city upon existing urban fabric is a more ecological way of looking at city-making as a regenerative and restorative process for human habitats. By viewing the city as a place for co-presence, urban planners and city-makers can look to the historical urban fabric which remains as a generative layer to be utilized in increasing the “dynamic density” that Durkheim [

56] refers to as the closeness that allows for the exchange of materials and ideas.

One way that Heritage Urbanism could be implemented in practice is for policy and planning to engage projects of ‘fabric repair’ in key areas. This would require a deeper understanding of the historic urban fabric and the conditions that created it, and is analogous to the project of “sprawl repair,” in which a fragmented suburban area is re-connected using locally appropriate historic patterns [

57]. Detroit provides a key national example of fabric repair in current urban planning and design debates with the planned removal of Interstate Highway 375 which currently separates the downtown core from neighborhoods to the East. According to planning documents, the purpose of this project is to improve connectivity for pedestrians and to enable potential economic development activities [

58]. Another early step would be to acknowledge that existing heritage patterns should be preserved and grown upon, rather than being further fragmented (as has happened with recent disruptive district-centric constructions around casinos, sports complexes, educational and medical districts). In all cases, we must not treat historical buildings and cityscapes as frozen in time, or looking to the past, but instead forming a dynamic and evolving matrix—a stark contrast with the outdated ‘blank-slate’ thinking of the past.

7. Conclusions

We have examined the challenges for urban planning and design professions today with a focus on the context of declining post-industrial cities through the case study of Detroit, MI, USA. As in every kind of project, there is a perennial challenge of over-specialization within disciplinary “silos” [

59]. Related to that challenge, urban development must also respond to different, and sometimes competing, value dimensions, for example, real estate values, historical values, and the values of professionals who seek to impose a manageable order in their work. In general, these values are based on self-interests or expert perspectives and, consequently, do not necessarily reflect a broader view on urban heritage, defined here as an infrastructure commons. However, what we need to see and understand, in the context of our short analysis, is that urban heritage—with its physical and social qualities—plays an essential role in co-forming the city’s spatial continuum. Urban heritage thereby serves as a platform for the interplay between different features in the spatial continuum and their relational meanings. In that sense, it is an essential domain for contemporary urban planning and design aiming at urban development.

Profound and highly visible changes in urban structures and spatial boundaries are transforming the notion of urban heritage as we know it and impacting the lives of human beings and the integrity of ecosystems. As urban planners and designers, we must be cognizant of the effect that our interventions in space will have and how forces of structural change contribute to shape the urban landscape and its heritage [

60].

The urban landscapes and structures that we provide in this way, and the built objects that we design, affect people and spaces directly and indirectly. They form habits and create ways of life and they give the user a chance to pursue individual happiness and to create relations to other people when embedded in space and time. The urban totality that emerges from this process affects people’s experience, stimulating or limiting how people live their everyday lives [

42]. Urban planning and design becomes inevitably, as Malcolm McCullough [

61] nicely puts it, an agenda for situated design to compare place and space, place and community, or place and ‘placelessness’.

We have argued that the model we call ‘Heritage Urbanism’ can be used as a valuable ‘systems approach’ to regenerative city planning in the neighborhoods of Detroit. We propose that, building upon the benefits of previous planning models as we reviewed them, Heritage Urbanism provides essential resources to contribute to genius loci (sense of place), attachment, and healing experiences within the community. The regeneration of this ‘urban commons’ by many actors can build damaged social capital by re-establishing trust between communities damaged and mutilated by social, economic, political, and physical processes of shameful past decades. We posit that, through this, more aggressive use of heritage and preservation as an active city planning and urban design tool, city planners, historic preservationists, and citizens may engage with each other in new and beneficial ways.