1. Introduction

Urban food insecurity has developed into one of the planet’s most significant challenges, especially in lower-income regions such as Southern Africa [

1]. Given that significant parts of Southern Africa continue to urbanize at rapid rates, food access and the urbanization of food insecurity are expected to be among the most difficult governance issues facing the region in the twenty-first century [

2,

3].

For these reasons, my research has focused on analyzing the governmental, private, non-governmental, and household institutions which operate across scales and sectors in South African cities. Through qualitative, quantitative, and spatial methods, I have conducted hundreds of in-depth interviews, multiple surveys, years of ethnography, and statistical and spatial analysis [

4,

5].

While this research has produced new theoretical and empirical data, it has also highlighted key methodological challenges associated with food system governance. Although many food scholars have critiqued the concept of food insecurity as a depoliticized and individualized measurement and preferred lenses such as food sovereignty or food justice which critically examines and centers the power dynamics of food systems [

6,

7], I have utilized the concept of food security to denote when food is available, accessible, nutritious, and culturally acceptable to people in different local settings [

1,

8,

9]. In this context, the concept of food security has been fruitful in highlighting the spatial inequality intrinsic to South Africa’s urban food system [

1,

8]. To this end, this paper critically examines how institutional power dynamics and the structure of South Africa’s urban food system have limited the quantity, quality, and type of data collected and the scope of food research and policy as a result.

In short, my research has indicated that key research gaps exist in the field of urban food systems research. To start, while many non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and other local institutions speak openly with researchers or share their data, key governing institutions such as the central state and private agri-businesses often refuse to speak with scholars. This has not only limited access to data on food system flows and operations, but it has also resulted in a significant research gap about the principal institutions in food systems, as scholars tend to disproportionately examine alternative food movements or other localized players. Also, given the range of informal livelihood strategies that urban residents utilize to access food across the globe, more scholarship is needed to understand the innovative ways that people navigate pathways to food.

The structure of the paper is as follows. After discussing the existing gaps in the literature on urban food systems, this paper critically examines the reasons for gaps in this literature, with attention to the methodological limitations and power dynamics which shape the access and collection of data to interrogate food systems in South Africa. This includes attention to two case study institutions. First, the principal power institution of the state, and, second, the informal institution of the community-based organization (CBO), a type of civil society organization (CSO). Then, this paper concludes with a discussion about the consequences of these research gaps, new directions in food systems scholarship, and the type of methods which might help scholars and policy makers more accurately and thoroughly examine food systems in Southern Africa. While the experiences discussed here are not necessarily generalizable to all urban food systems, the state and CBO are analyzed in this paper because they effectively highlight the two key gaps in urban food system research, namely the principal power institutions and informal food institutions.

2. Existing Research on Urban Food Systems

Research on urban food systems has increased significantly, as scholars have studied the ways in which multi-scalar processes of inequality have shaped the production, distribution, acquisition, consumption, and waste of food. To this end, scholars have used a range of poststructural, postcolonial, and neo-Marxian theoretical frameworks to analyze issues pertaining to food security, food sovereignty, foodscapes, foodways, food deserts, food justice, and the right to food. This includes important research on the range of public, private, and non-governmental organizations which operate across scales and sectors in urban food systems in Sub-Saharan Africa [

1,

8,

10,

11,

12,

13].

In Southern Africa, city dwellers access food through a range of private, public, and non-governmental institutions [

1]. Primarily, these centers are in the cash economy, with formal food vendors, such as supermarkets and food retailers, as well as street vendors, spazas, small shops, and more informal markets key to food access. In addition, governments provide food through national, provincial, or municipal food programs [

14], and CSOs manage local food pantries, creches, soup kitchens, community gardens, and other local food movements [

4,

5,

10]. Households also engage in a variety of more informal food practices to ensure access to food [

1,

8]. These include the sharing, gifting, and scavenging of food across households and communities. In this way, the informal livelihood strategies are often as important as food outlets in the formal food economy. In this paper, informal food activities are defined by their non-formalized human and financial resource structure and their lack of trackable or registered activity with the state [

1,

5,

15,

16].

While the literature on urban food systems in Southern Africa has increased recently [

1,

8,

16], key research gaps exist in the field of urban food systems research. Foremost, scholars often focus on alternative and local food institutions without adequately addressing the role that principal food systems institutions such as the central state and private agri-businesses play in reproducing the structure of the food system [

3,

17]. Although it is true that some recent scholarship has been dedicated to the role of food retail in the Southern African context [

18] and food governance regimes and state formation in Southern Africa [

19], more scholarship is needed which speaks to these important aspects of the food system.

In addition, a second research gap exists on the informal food economy. Although some important recent studies have focused on the informal food economy in Southern Africa (see [

20,

21]), more scholarship is needed to understand the innovative ways that people navigate pathways to food. It remains unclear how informal livelihood strategies operate in conjunction with or against the state and food businesses, as urban residents utilize a range of the informal livelihood strategies at the micro-scale to counteract broader social processes [

15]. Given the dynamic nature of these informal activities and the complex institutional context in which these social processes operate, it is crucial for scholars to develop methods which can generalize about the size, scope, and location of such activities [

4] and follow the development of local processes in relation to broader structural processes [

22,

23].

3. Gaps in Urban Food Systems Research

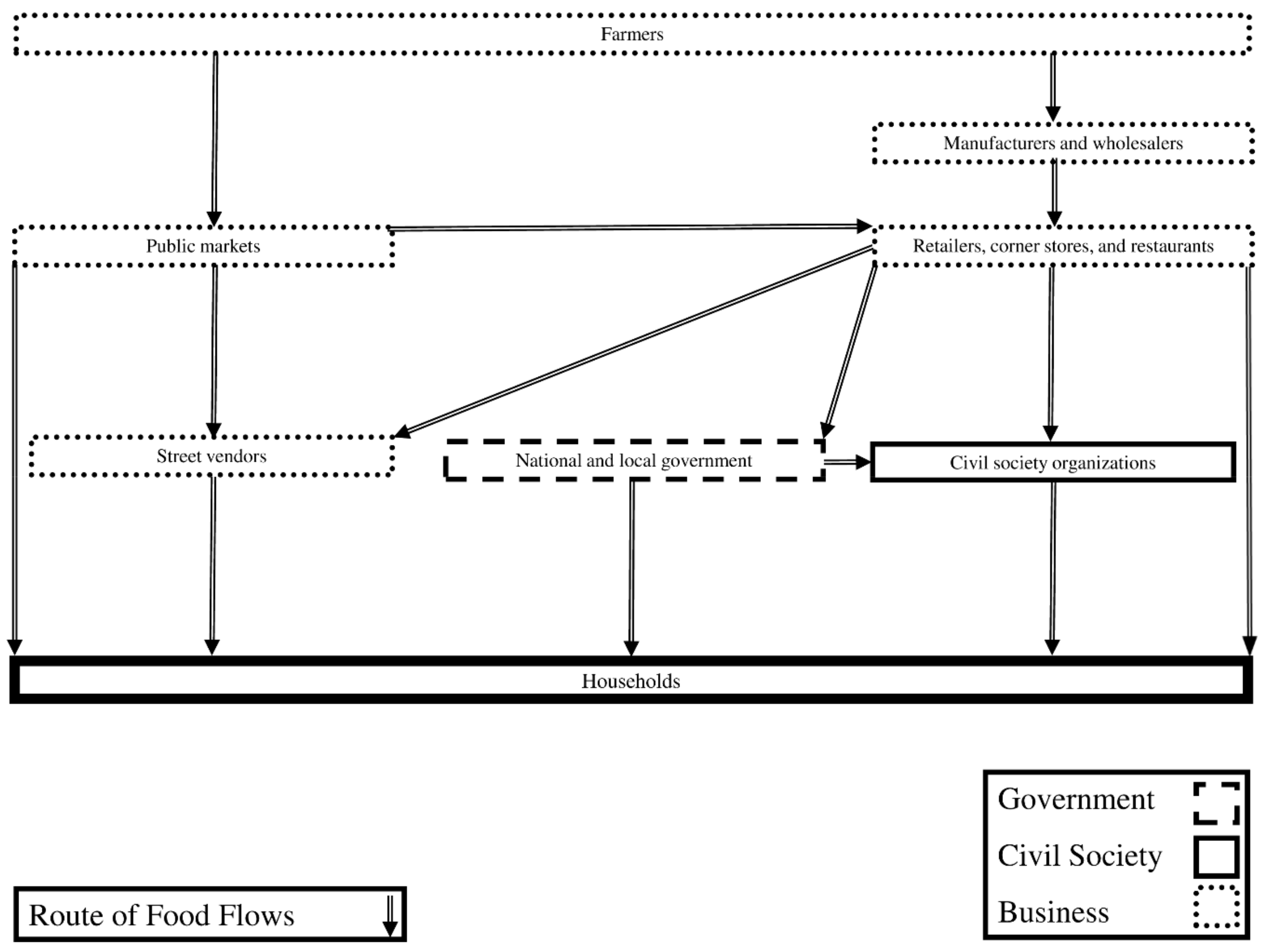

To understand the roles of institutions in urban food systems, I have utilized qualitative, quantitative, and spatial methods to examine the range of governmental, private, non-governmental, and household institutions which operate across scales and sectors in South African cities such as Johannesburg, Cape Town, Durban, and Pretoria. These institutions include farmers, food retailers, manufacturers, and wholesalers; corner stores, restaurants, and public markets; street vendors; national, provincial, and local states; NGOs, CBOs, and households (

Figure 1).

With each institution, I have employed a range of spatial, quantitative, and qualitative methods, when possible, to collect data on the size, scope, and location of key food system organizations and to generalize about the motivations driving different institutional mission goals or policies. However, a range of methodological limitations, such as uneven data access, poor data quality, issues pertaining to race, class, gender, language, and place of origin often limited my ability to collect high quality and reliable data (

Table 1).

To access farmers, I conducted in-depth interviews to reveal their livelihood strategies and motivations behind their work. Key methodological concerns included farmers’ anxiety over competitive information sharing and race, class, and power issues when speaking with researchers. Future data needs include quantitative metrics, especially for small-scale farmers in primarily black rural parts of South Africa [

17].

To access food corporations and the central, provincial, and local state, I conducted quantitative and spatial analysis of store locations and in-depth interviews of key corporate and government actors to understand policies. Key methodological issues included concerns over competitive information sharing, political impact of interviews, and lack of trust in outside experts. Future data needs include quantitative metrics on food flows and real motivations behind corporate and government policy [

5,

23].

To access corner stores, restaurants, informal street vendors, and households, I conducted in-depth interviews of entrepreneurs to understand how store owners, customers, and community members access food. Key methodological issues included race, class, privacy, language, and lack of formal identifiers. Future data needs include quantitative and spatial metrics on organization location and structure and qualitative analysis of informal food networks [

5].

To access non-governmental organizations and community-based organizations, I conducted in-depth interviews of NGO and CBO staff and institutional ethnographies, surveys, and spatial analysis of organizations to understand the structure, mission, and operations of NGOs and CBOs. Key methodological issues included race, class, privacy, language, and lack of formal identifiers. Future data needs include quantitative and spatial metrics on organization location and structure and qualitative analysis of informal food networks [

4,

5].

Given that the methodological details of previously completed studies are discussed elsewhere (see [

4,

5,

17,

23]), the purpose of the following sections is to critically examine the key gaps in urban food systems and the consequences of these gaps on current and future urban food systems research and policy.

3.1. Research Gap 1: The Powerful Institutions: The South African State as a Case Study

3.1.1. Existing Research on the State

According to scholars, the state is one of the principal institutions in the urban food system, as it operates and manages food policy, trade laws, food regulations, and food assistance programs [

14,

24]. While the central state sets national policy objectives, provincial and municipal state institutions often implement and manage programs. As multi-sector collaborations among public, private, and CSOs emerged in the last couple of decades, the role of the state has become increasingly streamlined, privatized, and decentralized. Although some have suggested that this governance shift has created an opening for local food organizations and communities to work with the state or enhanced democratic participation for local communities, many others have interpreted this shift as evidence of neoliberal governance which increases social and economic inequality. Regardless, the state remains central in the development of social or economic policy [

25].

In South Africa, a range of political economic, postcolonial, and other critical frameworks are needed to understand the extent of state experiences on the continent. Moreover, as noted by scholars working in this region [

26], urban governance is often impacted by neoliberal governance structures as well as the structure of the economy, government stability, inequality and poverty, and conflict related to race, gender, and place of origin. To this end, scholars need to recognize the historical contingent and dynamic nature of urban governance in divergent contexts [

27].

3.1.2. My Research on the South African State

Between 2007 and 2014, I utilized several methods to analyze the role of the central, provincial, and local state in South Africa, with research conducted for a total of eight months during 2007, 2008, 2009, 2012, and 2014 [

23]. This included a critical analysis of core government policy documents to understand the language, legal framework, budget, and political and ideological motivations behind state food policy. In addition, descriptive data analysis was conducted on the state budget to examine the size and scope of different national, provincial, and city food programs [

23]. I also attended multiple government workshops which focused on developing a food security policy for the city of Johannesburg. As part of this research, I conducted twenty-eight in-depth interviews with administrators at key governmental departments. Although interviews utilized a standard set of questions, the conversation was open-ended. Interviews were recorded and transcribed with agreement from the interviewee.

While the interviews were open ended, questions focused on the structure of governmental food programs, motivations behind different policies, and state perspectives on the causes and solutions of food insecurity. Even though some state employees eventually spoke with me after many phone calls, the discussion, numbers, and other information given to me were often pre-packaged, not critical, and sometimes not accurate. Very often, statistics were given which made the state look good and promote their successes. In this way, I was often given a ‘smokescreen’ of facts and figures without real access to information on key personnel, real numbers, and true motivations behind state policy. Examples of this ‘smokescreen’ are evident in the inaccurate numbers pertaining to the quantity and impact statistics associated with urban agriculture projects [

28], government program structure [

19,

23], and politically laden food scandals associated with food parcel delivery [

29].

To counteract this ‘smokescreen’ of limited or possibly inaccurate information, I received important data in three key ways. First, state employees often went off-script while still on the record, because they wanted to explain a state position further or give additional background. Second, my interviews with state employees sometimes gave me further insight into the logic which states use to make food policy decisions. Third, disgruntled state employees were often keen to give me an insider perspective on state policy. The main difference I found between the central and provincial or local state is that local bureaucrats were more likely to be disgruntled with national policy or unable to effectively communicate the official narrative without making mistakes.

My lack of access to state policies was arguably due to three broader issues [

23]. First, the most basic problem with South African governmental food policy has been the lack of a centralized and consistent approach. More than ten different government departments have food programs and the structure and characteristics of programs change often. Given that inter-departmental resources are contested by multiple units, many government administrators actively try to manage the way that their programs are being marketed. This provides further complications as policy is not only inefficient or ineffective, but also confusing and difficult for policy makers, government administrators, scholars, or community members to communicate or understand when there are so many different messages projected on food policy [

19].

Second, South African food policy is often disconnected from community experiences [

5,

23]. While national departments create policy, provincial or district level departments implement policy. This often creates distance between progressive abstract policies and challenges in actual places, and thus minimizes the potential for polices to be effective, as was the case in urban agriculture policy [

19]. For this reason, many government food policy administrators simply do not know how to communicate the experiences of policies, given that they may not have visited field sites or understand the structure, strengths, weaknesses, or real impacts of policies in real places. Given the presence of inequality across race, class, country of origin, and gender in South Africa, these policy-place disconnections are not uncommon.

Third, South African food policy is limited by the state’s active move to reconsolidate its power [

17,

23]. Sometimes this has been through the rewarding or withholding government contracts based on pre-existing personal relationships or nepotism, political quid pro quos on local zoning issues, or the distribution of food parcels in critical voting areas before major elections [

29]. While these actions have not always been malicious in motivation, they have often provided the state with an opportunity to reconsolidate its political power and co-opt food policies for its own gain. These examples suggest that the state might be deliberately limiting access or mispresenting food policies for its own gain.

While it might be inaccurate to characterize the South African state as neoliberal, given that state policies reflect the specific historic context and place-specific needs of various communities [

30], research suggests that my lack of access to state policy is likely due to institutional incompetence, such as the state’s lack of a consolidated food policy vision and disconnectedness from local communities, as well as the state’s efforts to reconsolidate its power and act corruptly [

5,

17,

23]. Although it could be debated whether these efforts by the state are intentional, these state governance dynamics have limited the ability of researchers to gain access to key state actors. This has resulted in researchers’ lack of understanding in food systems dynamics and ineffective policy formation as key state governance dynamics are poorly understood.

3.2. Research Gap 2: Informal Institutions: CBOs as a Case Study

3.2.1. Existing Research on Civil Society

In Southern Africa, CSOs have been conceptualized as the product of particular histories and social relations in local contexts [

31]. As noted by multiple scholars [

17,

32,

33], CSOs can be differentiated by function form, and mission. This includes NGOs, CBOs, and social movements (SMs). First, NGOs often operate programs through a network of local food organizations. NGOs are often relatively large, professionalized, located in wealthier parts of cities, and financed by wealthy corporate donors located within the country or abroad. Typically, they work with communities to manage urban agriculture projects or corporations to implement food philanthropy programs as part of corporate social investment strategies. In urban South Africa, NGOs include urban agriculture organizations, large food parcels schemes, and religiously based hunger organizations. Compared to CBOs and SMs, NGOs have a relatively formalized membership and funding structure with a board of directors or advisers which mandates official government registration and focuses their mission and day-to-day operations [

5,

17].

Second, CBOs directly operate a range of food programs in the communities they serve. They are small, informal, unstable, and dependent on local neighbors for funding. While NGOs may operate donor driven projects such as urban gardens or greening, CBOs often focus on basic needs defined by the communities they serve, not wealthy donors. These more basic needs programs can include soup kitchen meals, food parcel deliveries, day care, or other day-to-day needs of people in food insecure neighborhoods. Importantly, CBOs are often operating in a more precarious informal structure whereby they are often funded or managed by volunteer staff who self-fund and manage the organization. In urban South Africa, CBOs typically include soup kitchens, creches, food schemes, and other fragile organizations that are located in the country’s townships and informal settlements. These CBOs often have an informal or non-existent membership and are susceptible to extreme turnover due to resource scarcity [

5,

17,

34]. While CBOs are a key part of the informal food sector at large, they represent only the civil society aspect of the much larger informal sector. In this way, CBOs are classified in this paper as informal due to their non-formalized human and financial resource structure, priorities given to social networks over formalized food system flows, flexibility with in-kind donations and cash flow accounting processes, lack of registration with government or typical NGO protocols, and rapid turnover and ‘off the map’ activity intrinsic to the informal sector [

1,

5,

20].

Third, SMs often aim to contest structural causes of inequality rather than provide direct services to people. SMs often focus on the political economy of social issues, such as land reform, food prices, and living wages. Given that SMs are often broad, long-term, and connected to societal inequality, they are often defined in broader terms than simply ‘food movements’. Cities are often the epicenter of their activity, although land ownership has created food SM activity across the country. These organizations have broad and often informal affiliations rather than a constant membership given their constantly changing structure [

33,

35,

36].

While CSOs vary by size, structure, and distribution given the range of historical contexts across the continent, they are often critical pieces of the urban fabric in most cities. However, although CSOs have often been celebrated for their attention to local needs and flexible structure in many urban locations, scholars have noted their many institutional limitations. This includes their lack of accountability, unclear outcomes, fragility, lack of coordination, and inability to challenge existing power structures [

5,

30,

37,

38]. Regardless of their perceived strengths and weaknesses as organizations, CSOs have become an increasingly important set of institutions in local contexts, one which they play a critical role in shaping.

3.2.2. My Research on South African Civil Society

Between 2007 and 2014, I utilized multiple methods to analyze the role of NGOs and CBOs in South Africa, with research conducted for a total of eight months during 2007, 2008, 2009, 2012, and 2014. This research focused primarily on NGOs and CBOs, and less on SMs. To understand NGOs, I utilized surveys, statistical, and spatial analysis as well as participation observation and in-depth interviews to speak with NGOs in cities such as Johannesburg, Cape Town, Durban, and Pretoria.

In Johannesburg, I utilized existing databases of NGOs provided by the state and well-known advocacy organizations to build a comprehensive census of NGOs. I built and managed a survey of these NGOs to measure their structure, funding, institutional challenges, and relationships with community stakeholders and other key governing institutions such as the state and food retailers [

4]. In conjunction with the survey team I managed, I conducted snowball interviews to expand the list of potential organizations to interview. Then, I used descriptive statistics and spatial analysis to examine the size, scope, and location on NGOs in Johannesburg. While analytical statistics were not used given the small sample size and non-normal distribution of the data, descriptive data analysis and spatial analysis highlighted the socio-spatial patterns of NGO distribution in metropolitan Johannesburg [

4].

In addition, thirty-four in-depth interviews were conducted with people working at NGOs in Johannesburg, Cape Town, Durban, and Pretoria. These questions focused on the structure of NGOs; institutional challenges related to resources; race, class, and power in institutions; and, NGO relations in the community. In addition, when possible, I engaged in participant observation to understand how NGOs operated and the ways that community stakeholders interacted with each institution. Given that NGOs are generally resourced by private sources and located in middle class communities either locally or abroad, they tended to be larger, highly professionalized, and often tied to elite networks [

38]. For this reason, employees at NGOs were not only open but often encouraging of academic connections as they had similar educational backgrounds, maintained activist pasts, or realized the value of promoting their organization to outsiders, especially elites. This led to relatively open access for research, but sometimes contributed to an inflated view of NGOs as they were often highly visible to the public and actively reinforcing the success and meaning of their work. This often produced excellent qualitative data but limited the amount of high quality quantitative or spatial data to generalize about the scale of NGO work.

Between 2007 and 2014, I conducted thirty-six in-depth interviews with people working at CBOs in South Africa, with research conducted for a total of eight months during 2007, 2008, 2009, 2012, and 2014. Although interviews utilized a standard set of questions, the conversation was open-ended. Interviews were recorded and transcribed with agreement from the interviewee. These questions focused on the structure of CBOs; institutional challenges related to resources; race, class, and power in institutions; and, CBO relations in the community. When possible, I engaged in participant observation to understand how CBOs operated and the ways that community stakeholders interacted with each institution. CBOs operated a range of food programs for vulnerable populations and tended to be highly dependent on resources internal to the lower-income communities they serve. In this way, CBOs were relatively disconnected from elite multi-scalar networks of money and resources that NGOs access.

While some CBOs operated in place of deficient state food programs, others worked with national or international organizations. Additionally, while some NGOs had a global reach, many CBOs were localized and deeply embedded in particular places [

4,

5,

34]. In contrast to NGOs, CBOs were often hard to find due to inaccurate addresses, lack of phone access, or complete closure. In addition, people at CBOs were also sometimes less willing to speak with white researchers who were asking questions about the structure of their organization as this line of questions was often viewed as state surveillance [

5]. In this way, privacy was a significant concern among many. These methodological challenges are problematic, given that CBOs are such a critical piece of the informal food network in many Southern African cities.

Researcher access in the informal sector was extremely uneven, as many people were concerned about privacy or that I might be working or collaborating with the state or capital interests. In other cases, CBO managers were quite open with me. While qualitative data were often rich, quantitative and spatial data on the size, scope, and location of informal sector were significantly limited. This is problematic, given that informal livelihood strategies are significant in African cities as a percentage of the overall food system. However, the dynamic nature of the sector limits scholars’ ability to access, measure, or understand the various livelihood strategies which people in African cities utilize [

5]. Clearly, there are gaps in terms of how researchers and policy makers understand CBOs in Southern African cities.

As noted by scholars [

15], urban residents have engaged in innovative informal livelihood strategies to create order and survive in what is often a difficult living environment. This has often meant that city dwellers have developed new methods of accessing food outside the cash economy. Importantly, scholars have noted that this often necessitates a relational approach to understand the various pathways that people utilize NGOs and CBOs to access sufficient quantities and types of nutritious food [

22,

25].

4. Discussion: Consequences and Future Pathways to Overcome Gaps in Urban Food Systems Research

This paper has discussed the methods used to analyze urban food systems and the limits of these methods to understand the structure and complexity of food pathways in South Africa. Through the case study of the state and CBO, evidence in this paper has suggested that the structure and institutional power dynamics in South Africa’s urban food system have limited the quantity, quality, and type of data collected on key food institutions.

While many local food organizations are accessible to researchers, key institutions remain understudied, especially key ‘power’ institutions, such as the central state, and the informal sector, including CBOs and other informal social networks. Even though many sympathetic households, NGOs, and local state players speak openly with researchers or share their data, key governing institutions such as the central state are often reluctant to collaborate with scholars.

Very often, governmental administrators have refused to speak with researchers or give limited information due to concerns over the political impact of conversations with university researchers [

24] and a broader lack of trust in outside experts. Future data needs such as increased information on quantitative food flow metrics and information on the real motivations behind government policy are critical [

5,

23].

In regard to informal sector players, such as CBOs, access is limited by a different range of factors, as key methodological issues such as race, class, gender, place of origin, privacy and government oversight, language barriers, and lack of formal location markers make the collection of data severely limited. Future data needs on the quantitative and spatial metrics of organization location and structure are important yet extremely difficult to attain [

5].

This set of methodological limitations has not only lessened access to data on food system flows and operations, but it has also resulted in a significant research gap about the most important institutions in food systems, as scholars tend to disproportionately examine local food movements, urban agriculture interventions, and other smaller localized organizations.

While my research on urban food systems has produced new theoretical and empirical findings on urban food systems [

4,

5], it has also highlighted key methodological challenges associated with food system governance. Although my research in South African cities was designed to focus on all institutions in urban food systems, most of the key findings relate to civil society, especially NGOs and alternative food movements and their friction with the central state. Even though these findings are important as they speak to the limits of local food organizations in cities, the quality and quantity of research is constrained by interviewees’ concerns over data access, data quality, privacy, and broader issues of ethics.

In particular, while many food scholars critique the central state and agri-businesses for their contribution to an unjust food system, my research in South Africa suggests that real access to these institutions is often limited. For this reason, key data on key food institutions are often not available in studies or only analyzed in an abstract manner. Also, interviewees’ concerns over privacy and lack of trust of outsiders often limits the ability of researchers to examine the ways in which urban residents contest and negotiate urban inequality in many vulnerable contexts.

In addition, given the range of informal livelihood strategies that urban residents utilize to access food across the globe, new methods are needed to understand the innovative ways that people navigate pathways to basic needs [

39,

40]. As noted by scholars [

1,

15], city dwellers have invented new means of accessing food beyond the market economy. This has included the sharing, growing, and bartering food as well as creating new pathways through new informal job opportunities or alternative income sources. Given the dynamic nature of these informal activities and the complex institutional context in which these social processes operate, it is crucial for scholars to develop methods which can generalize about the size, scope, and location of such activities [

4] and follow the development of local processes in relation to broader structural processes [

22,

25]. This is both a methodological and theoretical challenge which is critical to the future of food and development scholarship in more than just Southern Africa, but also much easier to promote than to implement in the field.

Given the methodological challenges associated with understanding the central state, corporate food businesses, and the informal food sector, new methodological interventions are needed to understand the range of institutions operating within urban food systems. While this might include mixed method approaches, it also likely includes methodological approaches which are less structured or exist at the edges or space between formal methods. These more open or unstructured methods might be fruitful in complementing more traditional qualitative, quantitative, and spatial methods. Regardless, as noted in this paper, scholars must continue to think creatively to overcome these methodological limitations in food systems research; otherwise, we are destined to reproduce the same scholarship which disproportionately emphasizes the power of alternative food movements, NGOs, and other local food organizations [

41].

To this end, there are a number of critical research frontiers which exist in food systems scholarship. To start, more research is needed to examine the principal food institutions in urban food systems with a focus on the state and food corporations. To understand the structure and motivations behind state and corporate food policy, researchers should develop a triangulation methodological strategy whereby different sources of data are positioned in relation to each other to more accurately understand the phenomena in question [

42,

43]. This includes a critical examination of written policy documents and verbal communications of food policies; interviews with administrators at various levels of government and corporations who craft, design, and implement policy; and, measurement of the impact of different policies in places by speaking with a range of partner organizations and community stakeholders.

While there are significant quantitative and spatial data to be collected on the structure and scale of food programs and their impacts in communities, a significant portion of future research should be qualitative. This includes speaking with people who create policy (central state and corporate administrators), implement policy (provincial and local state administrators and local retail staff), and are impacted by policy (community stakeholders). Given the preponderance of paid consultants and in-house researchers reproducing the positive image that many powerful state and corporate food institutions hope to project [

44], it is important that independent researchers critically examine how food systems are conceptualized and how different institutions fit within these systems. Ideally, longitudinal studies would be developed which could measure the ways that different institutions participant, manage, and reproduce different structures within the food system. Moreover, many food policies or programs do not fit simply into tightly bounded geographical or bureaucratic conceptual boxes, as government and corporate food policies are the result of a flow of ideas and resources across scales. For this reason, it is vital that food policies are recognized as the result of contested and negotiated processes of development, as many ideas start in one part of the globe and are reimagined in another way in different localities [

22,

25,

45].

In addition, given the increased importance of the informal food sector and informal livelihood strategies as pathways to food security in cities, more research needs to examine the basic quantitative and spatial dynamics of the sector. This means that scholars need to do the hard work to count every person and food activity in the sprawling and dynamic informal food sector. This would inevitably be a very time-intensive and human and financial resource dependent endeavor since the sector is so large and so difficult to map and quantify. Unlike the broader societal movement towards abstract big data analytics, this work would have to be coupled by a high level of cultural competency on the ground as methodological challenges associated with race, class, gender, place of origin, language, privacy concerns, and government oversight all limit scholars’ ability to conduct this work in isolation without understanding the full cultural context at the ground level. In addition, it is critical that scholars couple this intensive quantitative counting and spatial mapping with extended ethnographic research to more fully understand how the informal food sector operates across communities and scales. This ethnographic work would also take significant time, probably years, to complete effectively in order to gain trust in different communities and to understand how informal food networks function. In this way, the various quantitative, spatial, and qualitative methodological approaches should be integrated in order to accurately reflect the complexity, dynamism, and cultural diversity of the rapidly growing informal sector in Southern Africa.